Rewrite

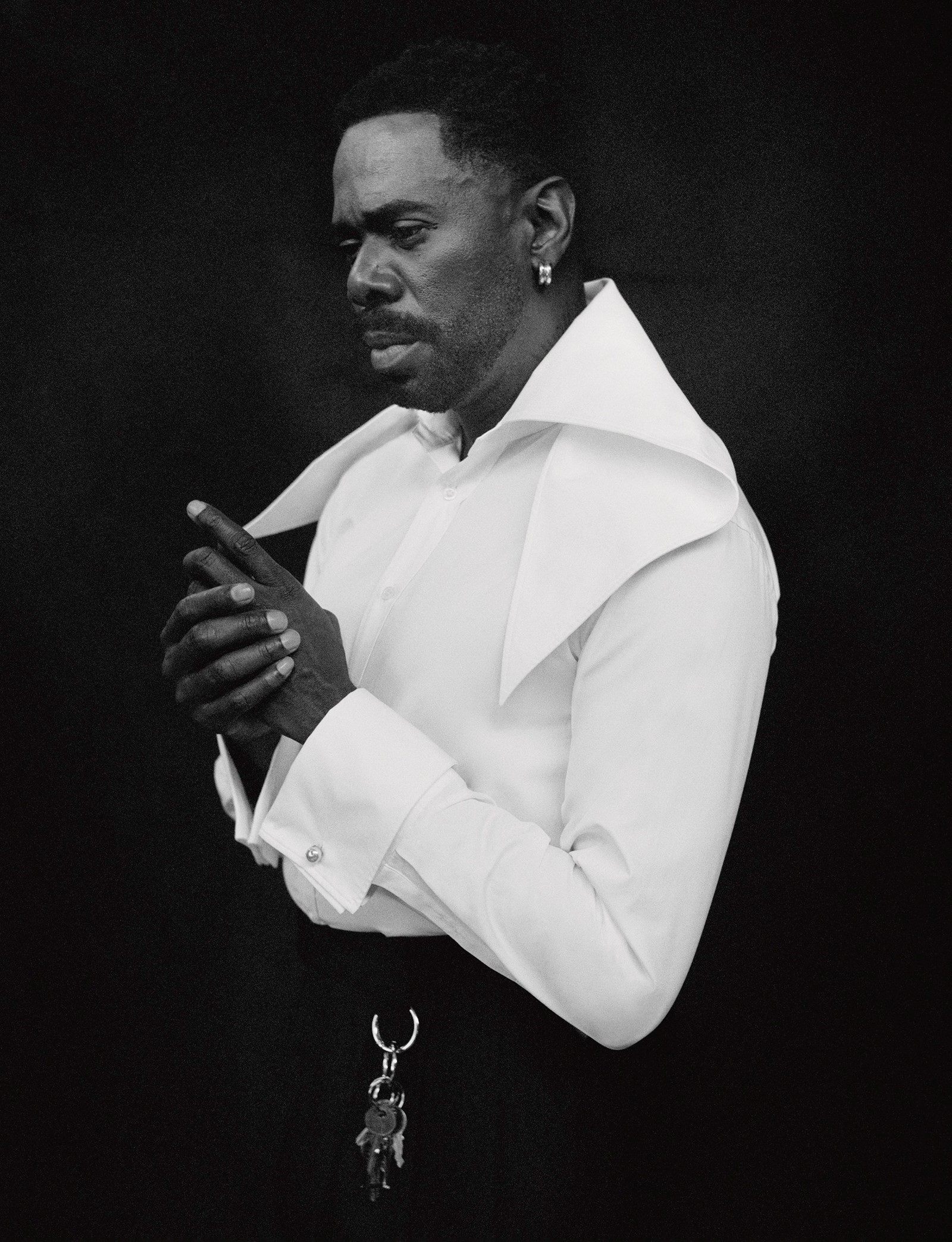

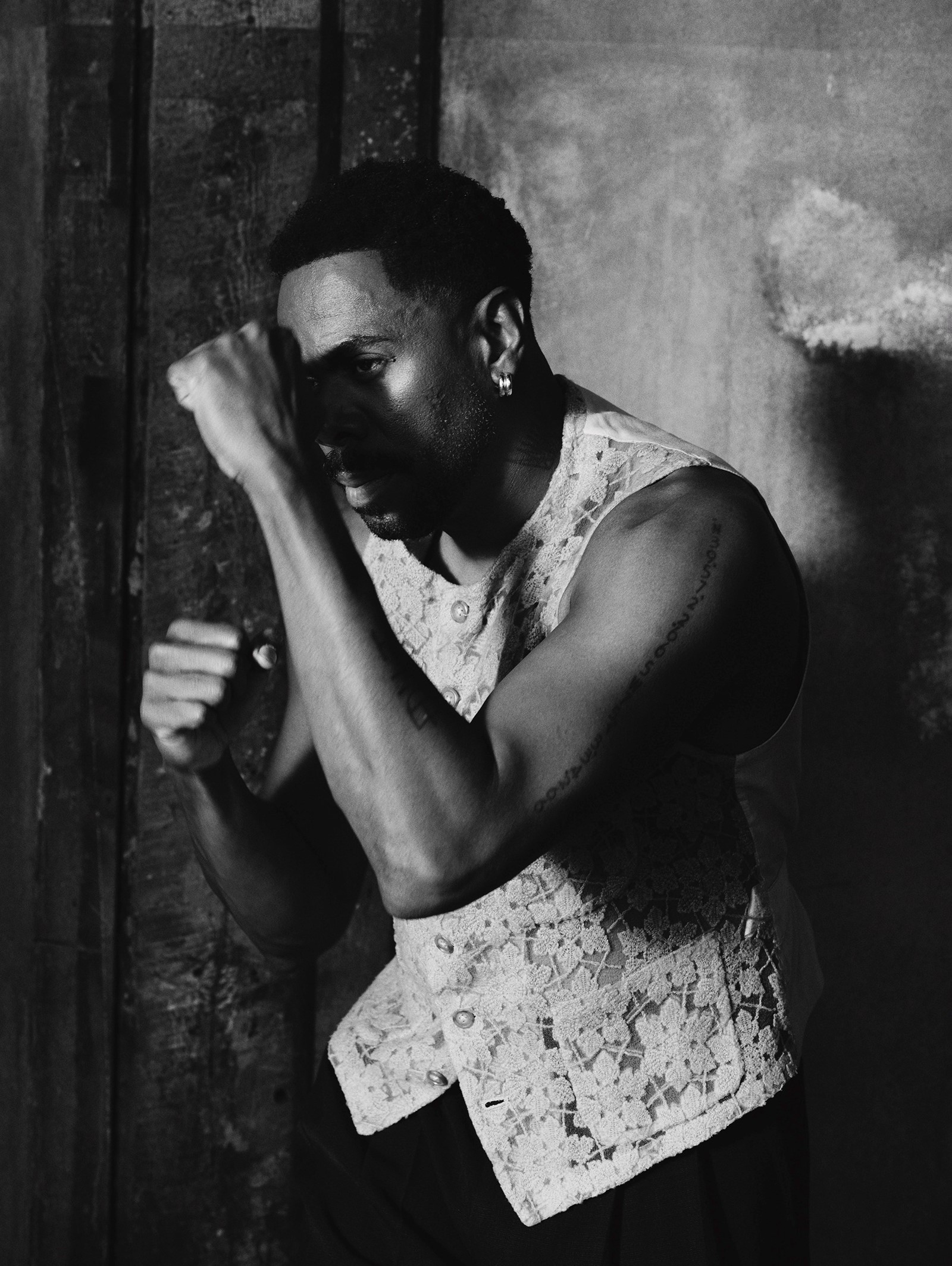

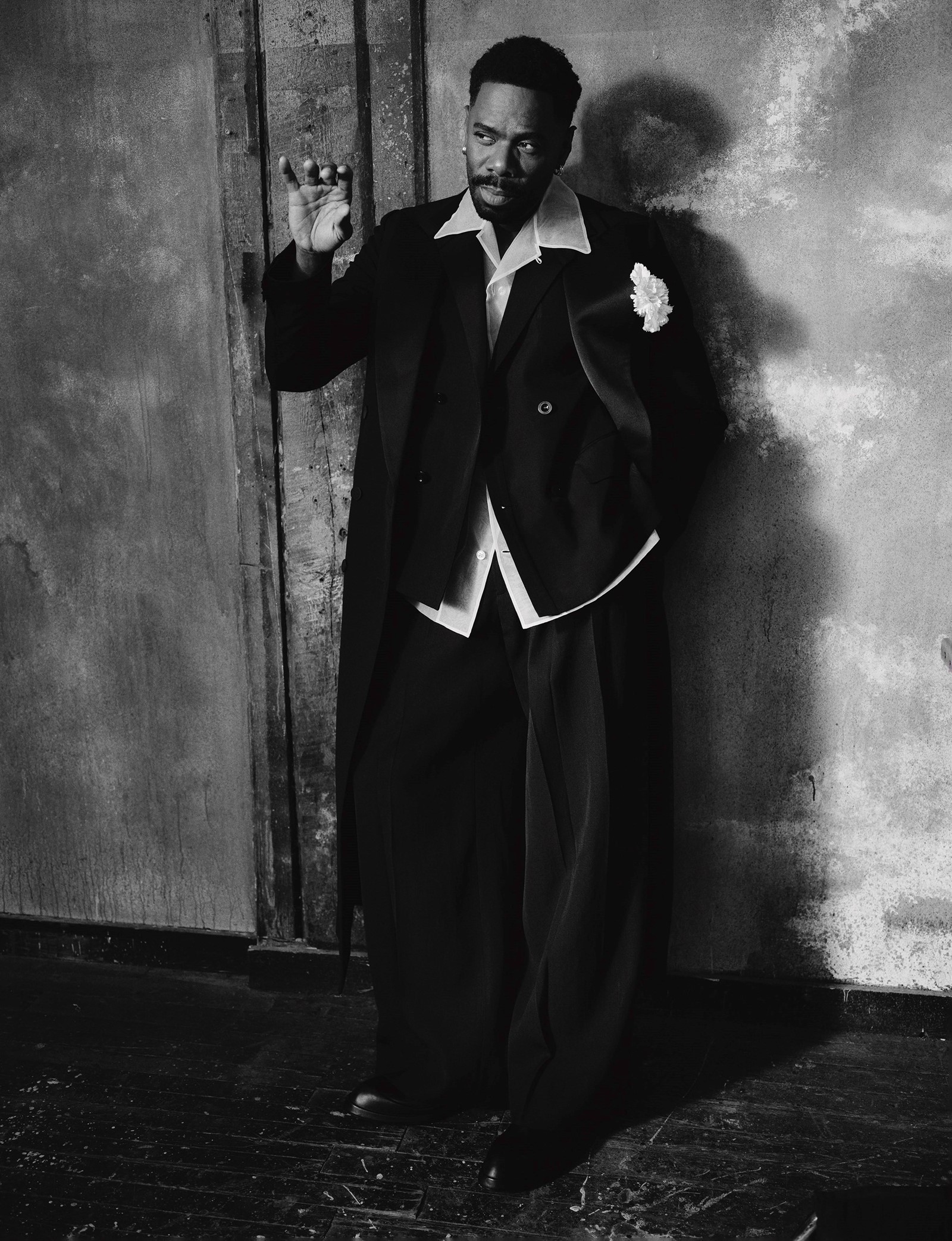

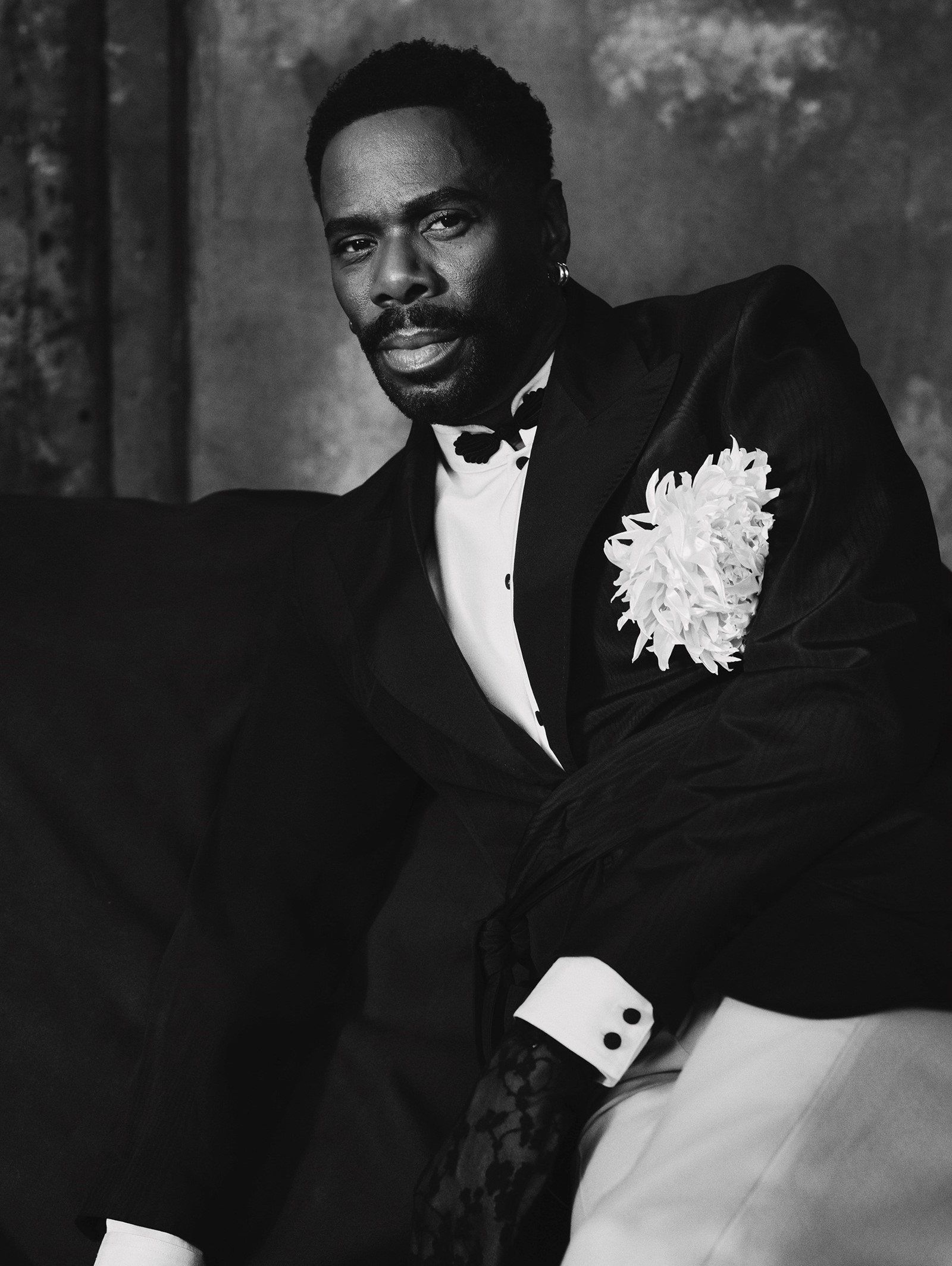

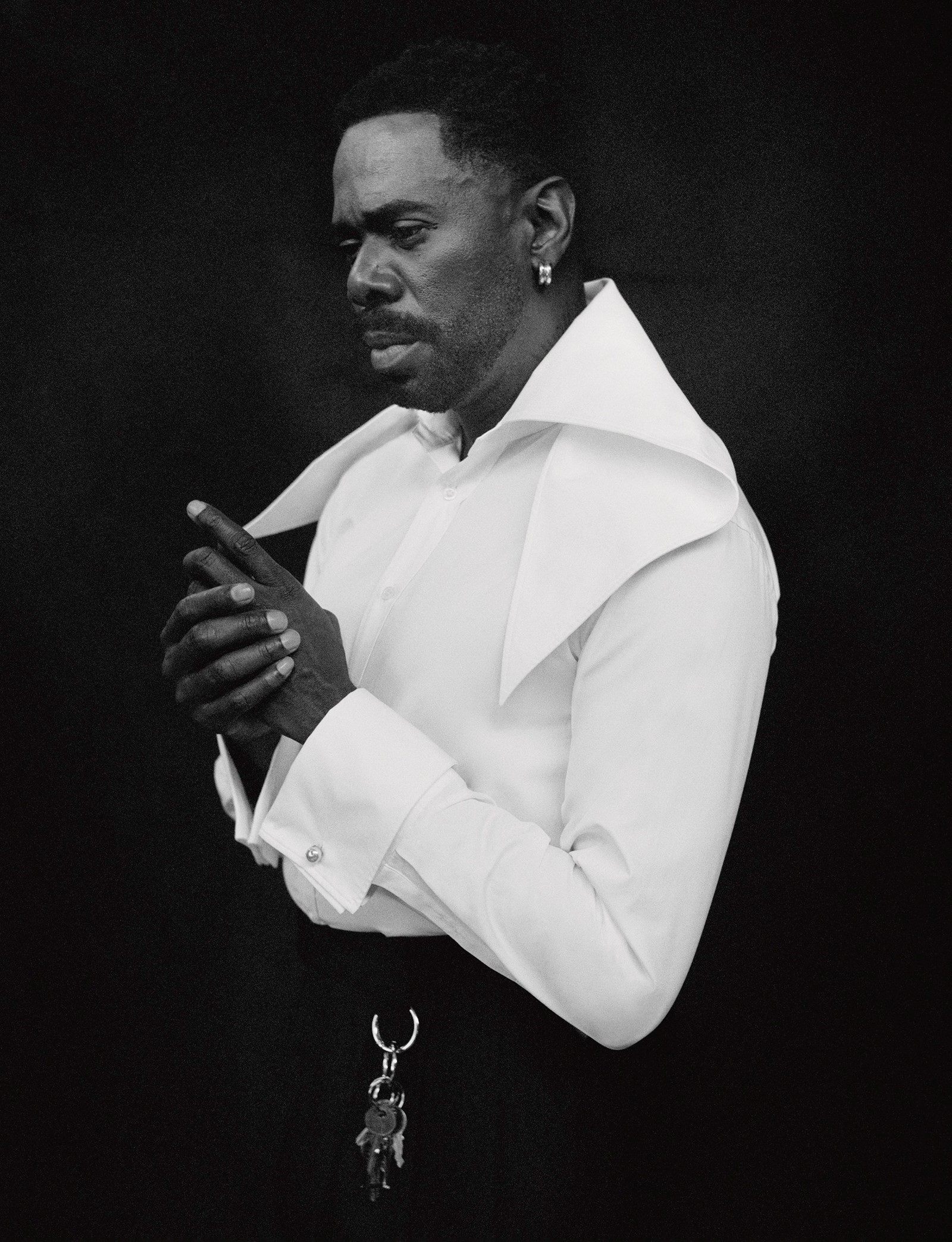

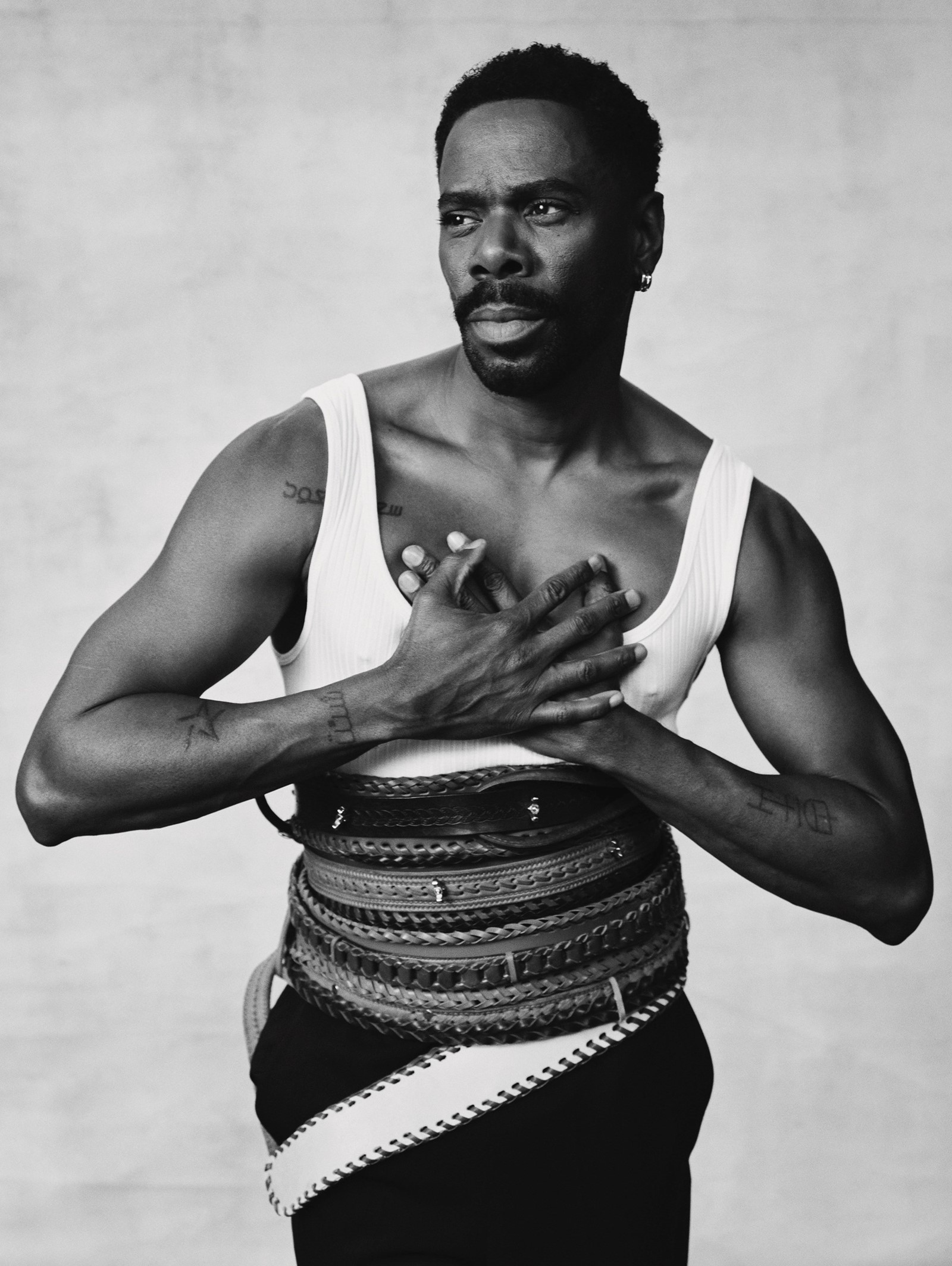

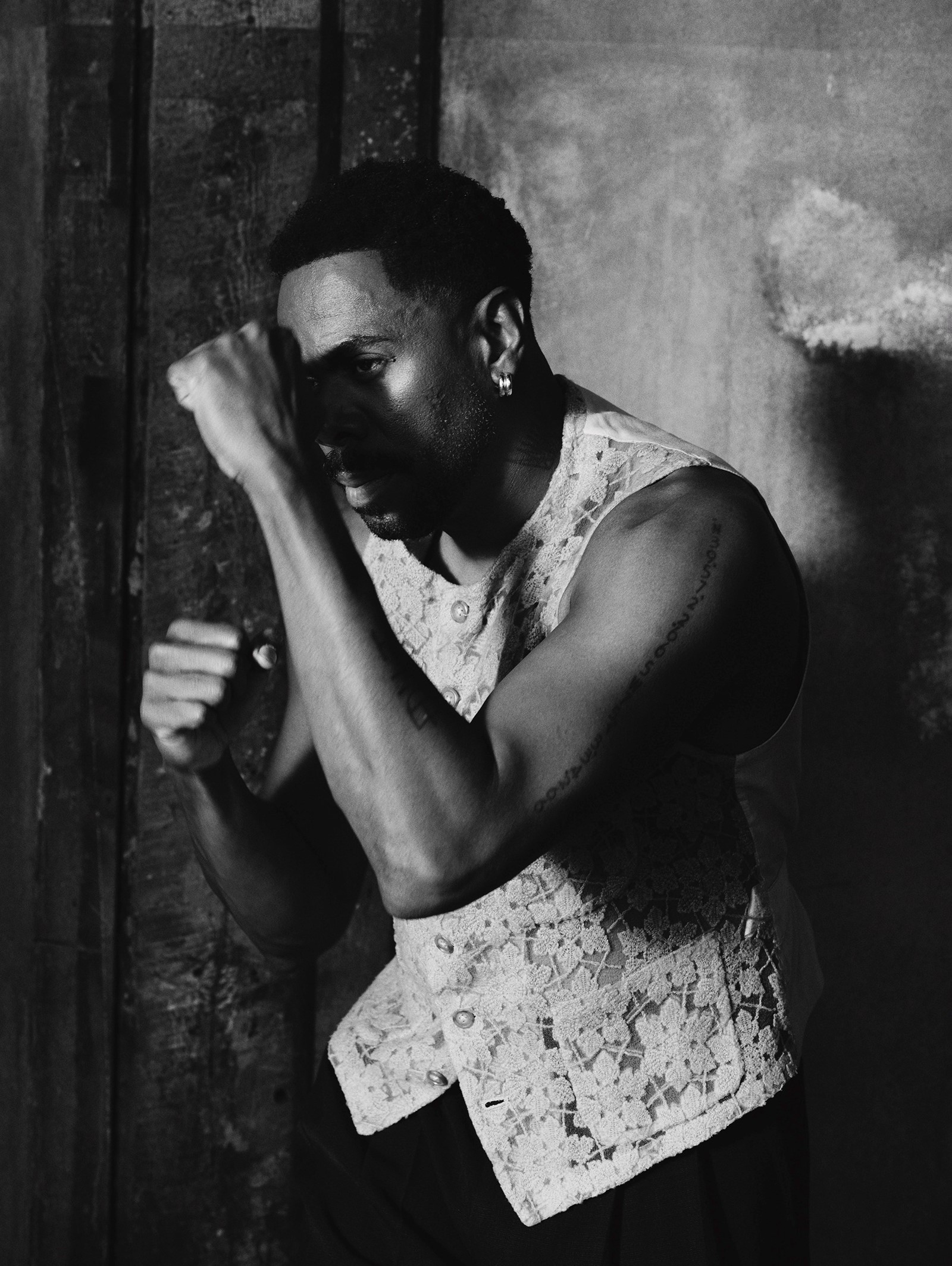

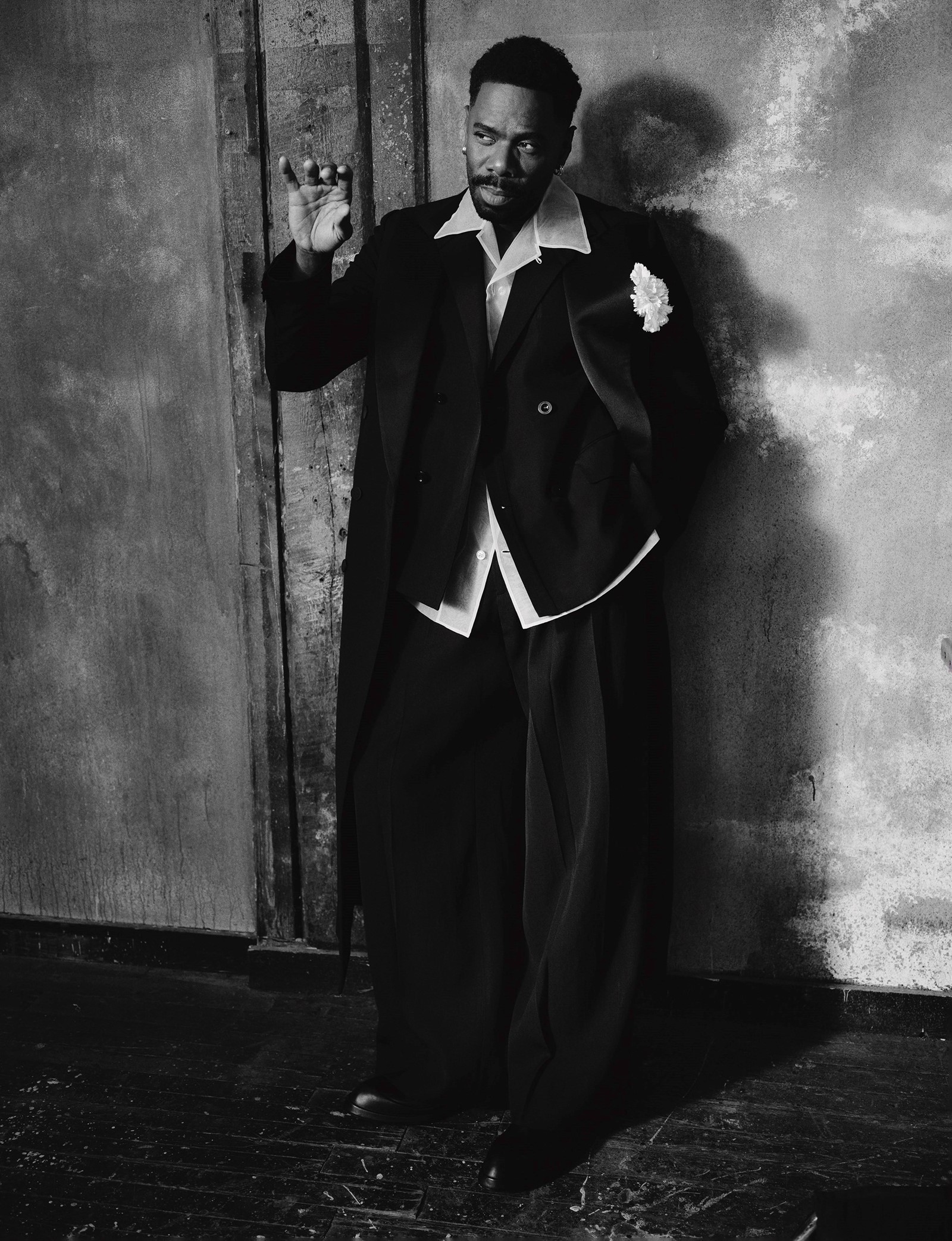

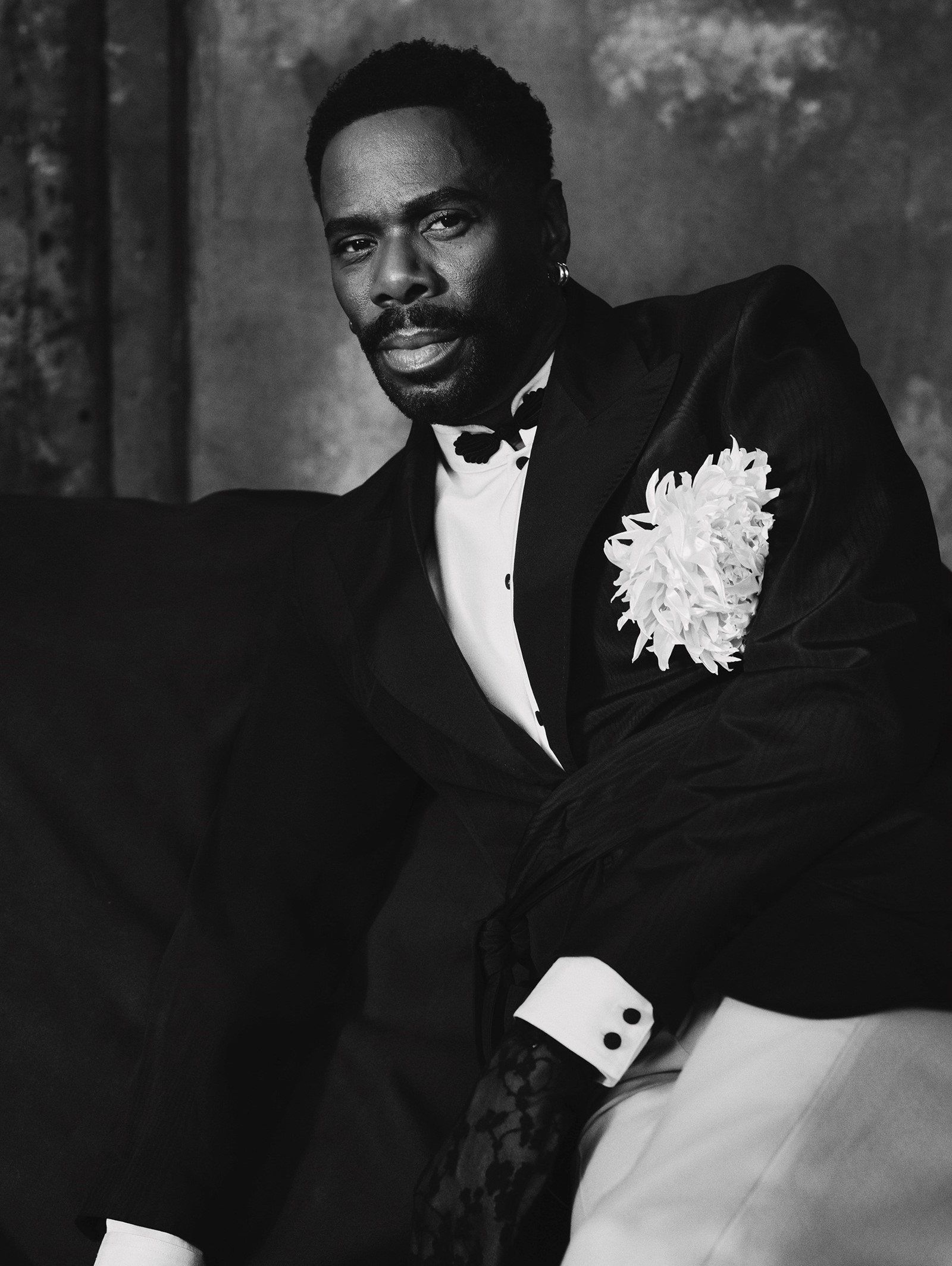

Lead ImageJacket, shirt with frog collar fastening and trousers by VALENTINO. His own earrings. Stylist’s own vintage flower brooch. And gloves by VALENTINO GARAVANIPhotography by Rahim Fortune, Styling by Raphael Hirsch

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine:

I hear Colman Domingo before I see him – as I rise through the arteries of an old building in Brooklyn. His laughter, deep and low as thunder, spills into the hallway as the lift doors slide open.

Next is his face – a sensitive, moustached, elastic face that morphs easily into that of a loving father (If Beale Street Could Talk), or snarling pimp (Zola), or abusive, capricious husband (The Color Purple), or incarcerated thespian drunk on hope and performance (Sing Sing).

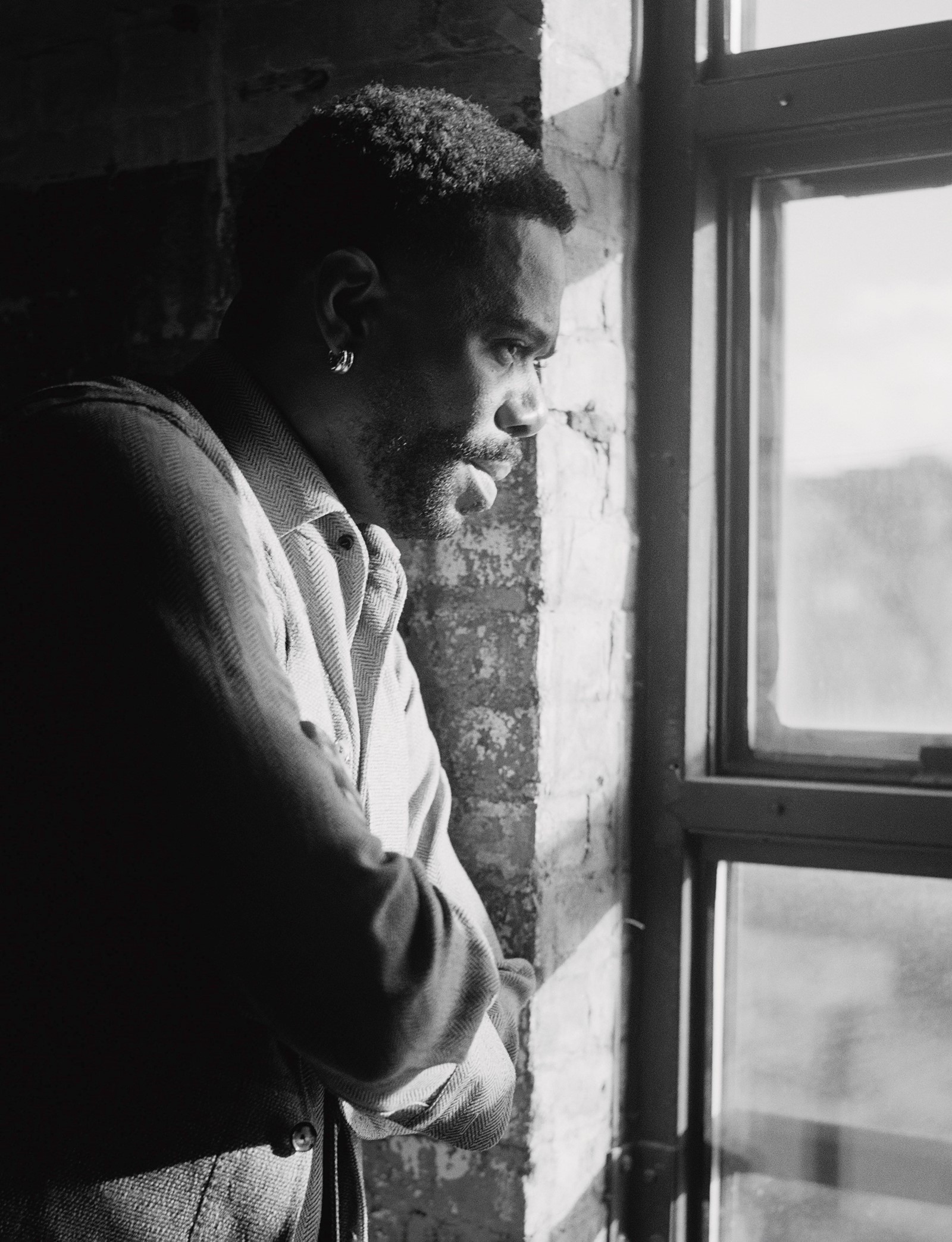

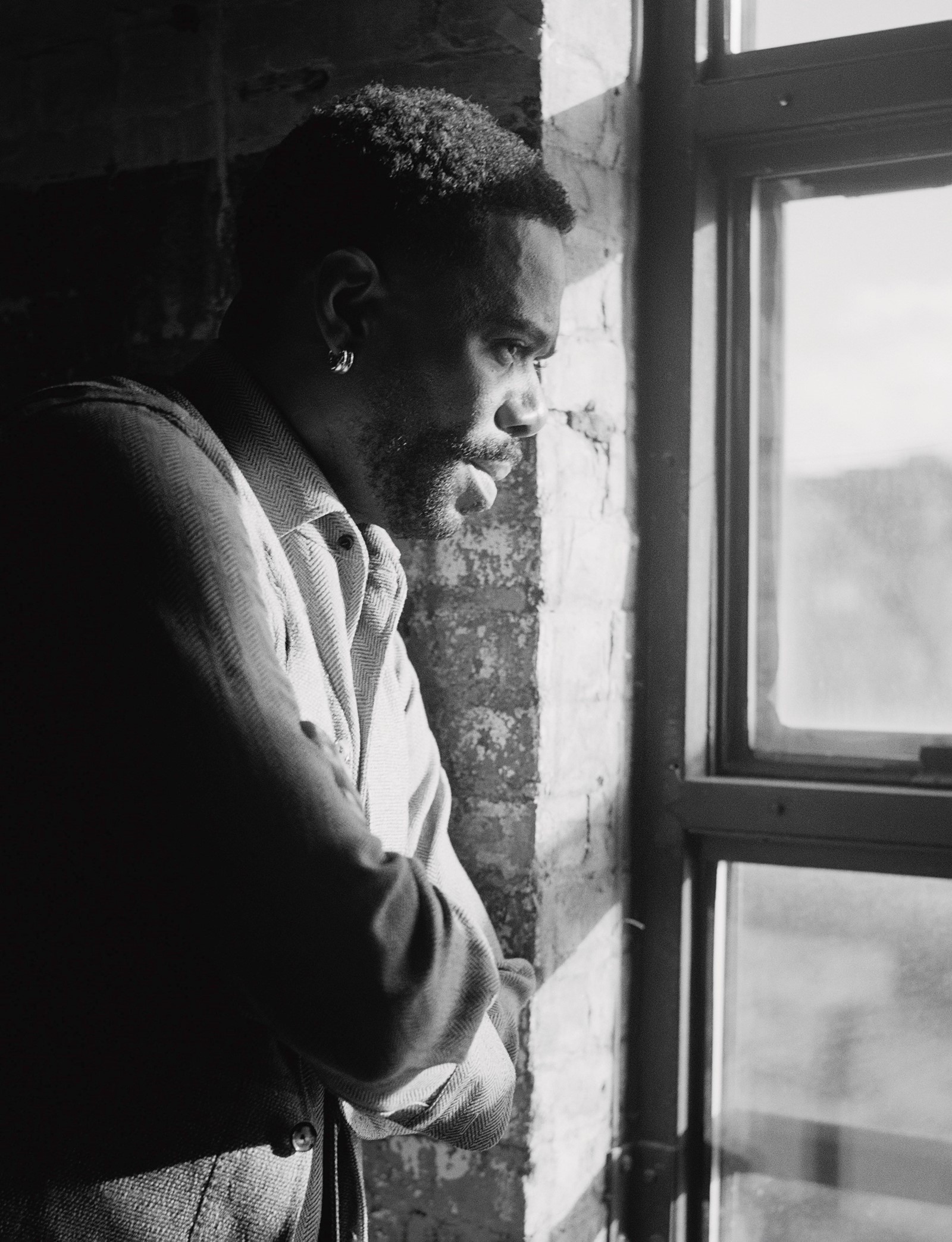

The studio in Greenpoint is all brick walls and wooden beams, with large windows that overlook the stormy East River and the diorama of Manhattan unfurling just beyond it. In 2001, following a decade as a fêted stage actor in San Francisco, Domingo moved to New York. He lived there for 16 years – because he is obsessed with reinvention and where better to remake yourself offstage than in a city that doesn’t care who or what you are, and in a rent-stabilized building that is affectionately known as the Home for Wayward Actors? Today, it seems impossible to imagine Domingo as anything other than an entertainer. I find him between shots, gliding across the wooden floors, humming and snapping to Marvin Gaye. (In A Boy and His Soul, a play Domingo wrote and starred in in 2009, long before Hollywood took notice of him, the actor referred to Gaye’s voice as “the sound of my heart, my feet, my eyes”.) He’s also making casual conversation with the crew, gesticulating in wide arcs as he speaks and dispensing from a silver tray small vanilla cupcakes, each printed with a photograph of him aged seven or eight, wearing a yellow top with a big Seventies collar and a gleeful, unselfconscious smile that’s missing a couple of teeth.

He offers a large hand for me to shake. “I’m Colman.” He is 6ft 2in and possessed of a theatre kid’s physicality and the sort of imposing vintage grandeur that holds the room. He is gregarious, though he was quite shy as a child, he says, and does not break eye contact in conversation. That laugh comes often and easily. Domingo wears clothes with flair. He is co-chairing this year’s Met Gala, where the theme will be Superfine: Tailoring Black Style. He is a Sagittarius, which perhaps goes some way towards explaining the edible childhood photos he’s imploring the crew to consume: his 55th birthday is in two days, on Thanksgiving, and the cakes are a gag gift from his team.

“Everyone expects me to throw this big party,” he says. It’s not an unfair assumption, since Domingo likes to dance, likes to sing. His friend the actor Natasha Lyonne once described him as having “bring the party” energy. But 2024 offered a sustained period of festivities, disco balls and red carpet appearances, which means that all Domingo wants to do now is go on an early-morning hike in Malibu, have dinner with some friends at their place, watch some television. “I just want to take it easy, because I feel like it’s been such an enormous year,” he says.

Since the autumn of 2023, Domingo has been on a tear. Rustin, The Color Purple, Sing Sing, Drive-Away Dolls … He spent several months in Toronto filming The Madness, which is, at the time of writing, the most popular television show on Netflix, and found time to contribute voice roles to a sci-fi adventure movie for the Russo brothers (The Electric State) and a forthcoming Spiderman series for Disney+. He’s starring in the biopic Michael, set to be released in the autumn, as the singer-songwriter’s father, Joe Jackson; he’s working on a comedy series (The Four Seasons) alongside Steve Carell and Tina Fey; and he’s appearing in an untitled Spielberg film with Emily Blunt, Colin Firth and Josh O’Connor, though he refuses to reveal any of the specifics. Along the way he has become a critical darling, picking up best actor nominations at the Oscars and Baftas, two Golden Globe nominations and Gotham Award wins, four NAACP Image Awards, an Emmy win for his role in Euphoria – and too many acknowledgments from various critics’ societies to mention here.

Turning 55, Domingo has arrived at a place he would never have imagined, despite more than three decades of acting. For years now he’s been a leading man trapped under the skin of a character actor, the guy directors would call on to add texture and feeling and his ferocious, trademark empathy to their projects. “I’ve always been the support – like, the one who took care of the soul of the company, and people depended on me for that,” Domingo says. But it seemed clear nonetheless, across dozens of films, that he had his own field of gravity. “I’m very aware that I’m having a glorious moment in this industry. And I don’t know how long that time will last. But I do feel like I’ve got the building blocks for it. Hopefully I can keep evolving and have a good time with it, because not everyone does. People always ask me if I’m enjoying the attention – and I absolutely am. Maybe it’s because it’s happened so late in my career that I don’t have those same complicated feelings about fame and success.” There’s still the weirdness of having to be on all the time and the knowledge that moving into the spotlight means sacrificing privacy and renegotiating boundaries. “But I feel really happy about this moment. And I say this without ego – I know that I took all the steps to get here and did all the hard work. None of it was handed to me. It wasn’t because I was lucky or because I was pretty. It’s because I took it. It’s because I had to take it.”

***

“I’m very aware that I’m having a glorious moment in this industry … Hopefully I can keep evolving and have a good time with it, because not everyone does” – Colman Domingo

In Sing Sing, Domingo plays (the real life) John “Divine G” Whitfield. He’s a literary sensation at the maximum-security prison in New York state. The drab, mass-produced uniforms and routine denial of his humanity have not obliterated his sense of self. There is still a human soul to bruise and buoyancy to puncture. Divine G is serving a sentence of 25 years to life for a crime he did not commit and he passes the interminable time by studying the law, helping other inmates with their cases and writing plays and novels, which he performs as a founding member of a theatre programme, Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) – a transformative non-profit organisation launched at Sing Sing in 1996 that runs in various New York state prisons to this day. He’s an anchor in the sanctum of the RTA, a deferential leader his peers look to for guidance and sometimes material. Domingo plays it gracefully, occasionally stripping back a veneer of poise to reveal a flash of self-importance, indignation, or annihilating despair; he relishes these moments, when the mask falls away to reveal the fullness of the person behind it.

As Sing Sing crescendoes, so too does the anguish of its protagonist. The centre – that hope, the sunniness that protects against the slow crawl of dread – cannot hold. There’s the way he’s the last person to disrobe and return to his prison uniform after the Shakespeare performance that opens the film. There is the slight disgruntlement in his frame when the other group members choose to do a wacky, nonsensical, time-travelling comedy over his own latest drama. There is the further deflation of his pride when he realises that one of his new peers, the rough and unpredictable Divine Eye (the brilliant Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin playing a version of himself), is auditioning to play Hamlet, a role that Divine G seems to believe is his birthright. And there is the way his face is drained of all its light when he realises just how stuck he is, that he will not be getting out soon or maybe ever, that all his dogged efforts to prove his innocence have meant nothing. “It’s a way for these men to get some rehabilitation and to get in touch with their feelings,” he explains of the RTA in a clemency hearing where his right to freedom is being considered. “And are you acting right now?” asks the sharp woman who will deny him it. The disbelief creases his forehead and parts his lips. The horror wets his eyes. Just a few scenes later he will fall apart completely – on stage, spit flying out of his mouth, tears now streaming down his face, his body tense and suddenly dangerous.

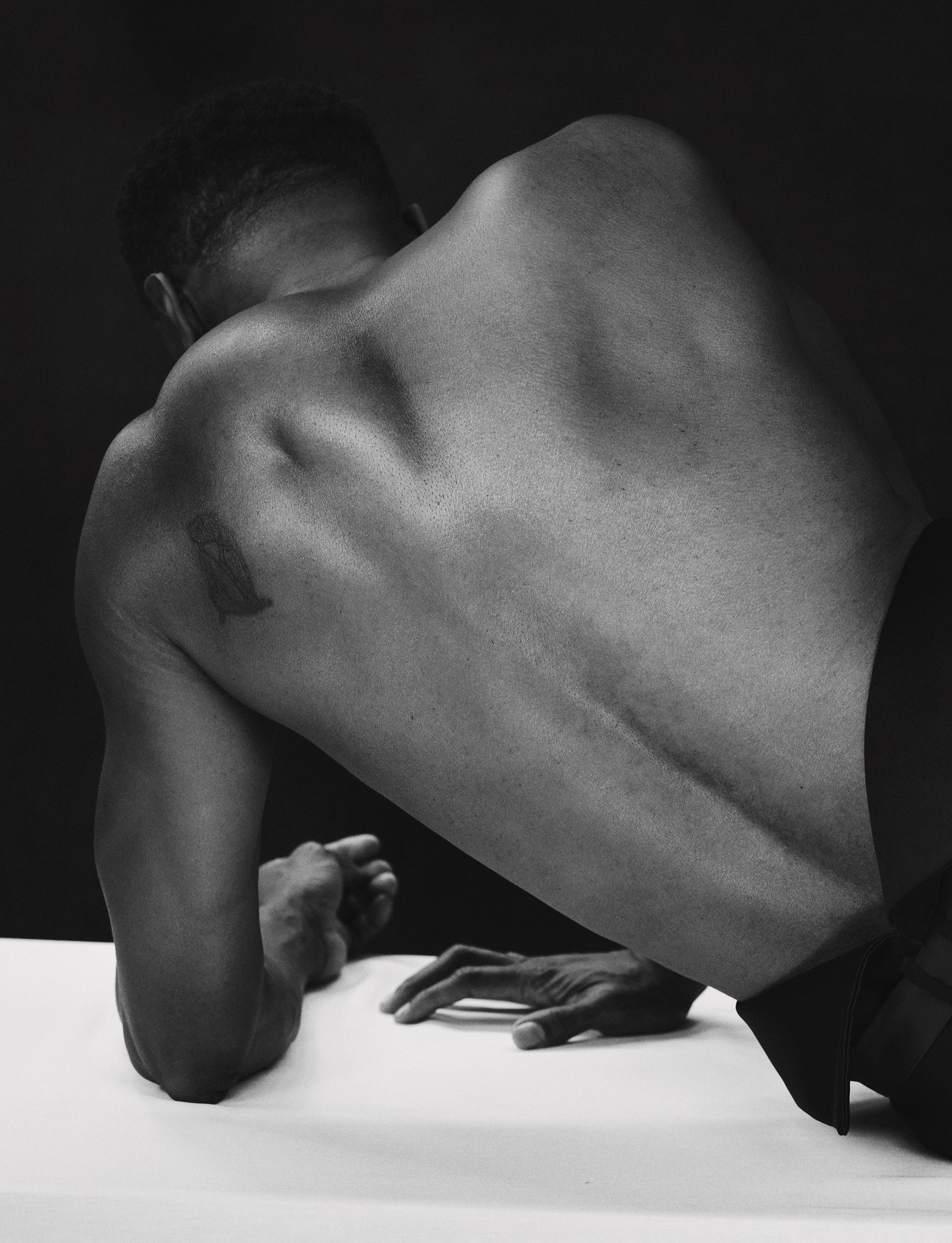

Domingo is expert at slowly reaching such emotional extremes. He can play it hard, can play it tough as nails, but as his character warns Divine Eye as he prepares for his role as Hamlet: “Anger is the easiest thing to play. What’s more complicated is to play hurt.” Domingo’s repertoire is punctuated with the occasional show of woundedness, but his performance as Divine G feels like the deepest cut. The first time he watched the movie back, it “wrecked” him. “It feels like the most vulnerable version of me is on that screen, this raw version without any polish at all,” he says. Part of this is a credit to his castmates, most of whom are former inmates who went through this programme themselves; the candour and realness of their performances, particularly Maclin’s eruptions of hostility, forced him to reach down into himself and produce something honest. “I grew up in inner-city West Philadelphia, so I know these guys – these men trapped in these institutions who nobody thinks about any more and who never had a chance,” he says. The other part is logistical: where most Hollywood studio films can take anywhere from 30 to 160 days to film, Sing Sing was shot in just 19, in the window Domingo had between finishing The Color Purple and doing pick-up shots for Rustin. “I think I brought more of myself into it,” he says, “because I didn’t have the time to prepare or be sure about anything.”

Typically, research is his favourite part of the process. “I wouldn’t say that I over prepare,” Domingo says. “But by the time I get to a set I’ve usually had four months of researching the details, making all these private decisions that nobody but me would know or care about. Like, how does this character move his hands? Is he comfortable with looking people in the eye? How does he have sex? How has he been hurt?” It was his decision to make his character’s uniform a touch too short, to suggest that it was issued a long time ago, long enough that Divine G had outgrown it. Before he was an actor, Domingo wanted to be a photojournalist; that he builds each character from a well of questions makes sense: “I need to download all of that information so that I can make a real, whole person and not someone who just fits the beats of the script.”

Take X, his violent, menacing pimp in Janicza Bravo’s Zola. In part because of sex worker Stefani’s willed unreliability, the viewer has very little context for him, no sense of who he is or where he came from or why he’s accompanying her and Zola on a trip to Florida. We don’t even have access to his real name until the film is almost done – all we know is he “takes care” of Stefani, a euphemistic term that Zola easily decodes. Domingo, alighting on these methods of deception and manipulation, elaborates the mystery. Sometimes, amid an exasperated fugue, his voice drops a register and his accent veers Nigerian. The effect of the sudden switch is jarring. “I decided that he was an immigrant who wants what everyone else seems to have, which is the American dream, but he doesn’t have access to it,” Domingo says. “He doesn’t have papers. But he does know women.” His interest in the humanity of the character led him to research the psychology of sex trafficking, to better understand the mechanisms of domination involved. That’s why he gave X that strange and comedic habit of coughing loudly when he’s peeing in the bathroom with the door open. “It’s this other way he has of trying to maintain control, by asserting his presence even when he’s in another room.”

“Eventually I realised that being a journalism major or being an actor, writer and director were all animated by the same desire, which is to understand other people” – Colman Domingo

Much like his character in Sing Sing – a movie about acting as a means of accessing humanity as opposed to artifice – Domingo believes his craft is a tool of empathy. His performances are always searching for tenderness, even, or perhaps especially, when the character feels beyond redemption. “I’m interested in fragility,” Domingo says. Playing Mister in The Color Purple was another way to study the psychology of abuse and to anatomise how violence ricochets. The villain is broken in his own way. “If I can get to the core of that, it’ll complicate him, and the audience’s empathy, because you’re forced to see the ways he’s also human,” he says. “I have to find the humanity in everyone. There’s always more behind the eyes.”

Which was part of the impetus for deciding to play Joe Jackson, a man known mostly by the public as a cartoonish representation of evil: he allegedly beat his children with cords and belt buckles, isolated them from other kids, forced them to call him Joseph (never Dad) and rehearse for hours on end, and is reported to have ridiculed Michael so incessantly about the size of his nose that the star surgically disfigured himself beyond recognition. “I’m very curious about characters who are complex and may have already been tried in the court of public opinion,” Domingo says. “Everybody has an opinion about Joe Jackson. The reason I wanted to interrogate his part of the story in this biopic is that I want to understand this man who created one of the most incredible artists of our lifetime. I want to deconstruct him. Everybody says he was a tough man, that he was just really hard. But why was he like that? Why did he have to be that way?“

“I think as an actor, we have to find that place of knowing a lot, and then unknowing it,” he continues. Without the possibility of discovery, the character remains static and bloodless, without revelation. “Everything about this career is about understanding psychology, understanding people. Everyone wants something – if you can figure out what that is, then you understand the person. In that way, acting is a bit like flirting.” You can get to the root of desire.

***

Domingo’s mother worked for a bank and her husband sanded floors. He was raised the third of four children in a home that was filled with soul music: Marvin Gaye again, the Isley Brothers, Teddy Pendergrass, Earth, Wind & Fire. Always there was the crackle of vinyl, the smouldering slow jams over the radio airwaves. Really, Domingo was more likely to be a musician than an actor, although he never really set out to be either (aside from some violin lessons). His mother, Edith, after whom he named the production company he runs with his husband, Raúl, was much looser in how she raised him and his younger brother than how she cared for his older siblings, whom he describes as “salt of the earth” people. “They grew up with this sense that you’re supposed to get older, find a good job somewhere and then get married and start a family,” he says. “But with us she encouraged us to do whatever made us happy, to be joyful and to be of service to others, whatever form that might take.”

In high school, he wore his older siblings’ hand-me-downs and did his best not to be seen. He didn’t speak much, trying to ensure he wasn’t beaten up. He says most of the people from that time would have been surprised by the career he has now – he preferred to be invisible, was more comfortable with observing than being observed. People wouldn’t know that he was gay if they couldn’t see him, if he kept quiet. He studied journalism at Temple University, in Philadelphia, and envisioned himself travelling to war-torn countries and documenting atrocities. He took portraits of actors as a side hustle. When he was selecting the courses for his first year, his mother encouraged him to take at least one class just for fun and he ended up on an introduction to acting course that helped him conquer any shyness. “It got me outside of myself and allowed me to try out different personalities and ways of being,” he says. Halfway through his first term, his teacher approached him and asked whether he’d ever considered acting as a profession. “I was 19 years old and he said to me, ‘I think you have a gift,’” he says. “That shook my whole foundation, because I think it was the first time anyone had ever said something like that to me.”

He started taking classes off-campus at the Walnut Street Theatre in his second year. “I was very shy about telling anybody what I was doing, because I was a little bit embarrassed and because being an actor felt special,” Domingo says. “It was just for me to enjoy and I didn’t want anybody to take it away from me or tell me I wasn’t worthy and couldn’t do it.” When he was 21, some friends who had moved to San Francisco invited him to stay with them and he accepted. He imagined it was a chance for him to become a whole, free person, an opportunity to begin a Big Life in a famously gay city. Though he planned to go only for a month or so, he stayed for ten years. “I lived in a studio apartment with three other guys, and it was so tight that my bedroom was a walk-in closet,” he says. (The metaphor is almost too obvious, although he came out to his family around this time.) He got a job bartending at a club that was next to a church and recognised the conversations with patrons as rich artistic material. To be the bartender was to play a role too, to be tasked with identifying what people want or need and meeting them there. Anyone could come through the bar doors, their heads filled with all sorts of strange thoughts. “Eventually I realised that being a journalism major or being an actor, writer and director were all animated by the same desire, which is to understand other people,” he says.

“I’ve always done everything and never sold myself short. If nothing else, I’ll never allow anyone to limit me on what I can play or do” – Colman Domingo

In San Francisco, he had all kinds of jobs: working in customer service at Macy’s, performing in a circus. On the side, he read Stanislavski and Uta Hagen and went to auditions. “I’ve never attached the word ‘struggle’ to my journey,” he says. “I thought, if one day you’re acting, the next day you’re bartending, the next you’re doing a temp job or teaching or doing a reading – I considered that to be the life of an artist.” He loved bartending, getting to know people and making cocktails and taking care of the bar. He felt liberated, like his life was exciting.

The first audition he booked was for an educational play called The Inner Circle, in which he played a high school student who receives a blood transfusion and becomes HIV positive. Gradually, he booked more work. He fell in love with Shakespeare. He acted in more plays. He did television shows. “I became a Bay Area theatre actor and sort of rose to the top of San Francisco,” he says.

But Domingo wanted to push himself as an artist, and in New York he expanded. He acted on TV and was luminous on stage. In 2007, he starred as a Dutch nudist, closeted choir director and German performance artist in a rock musical called Passing Strange, which opened on Broadway the year after its successful run at the city’s Public Theater. It earned him an Obie Award and the attention of Spike Lee, who filmed the play and later cast Domingo in his movies Miracle at St Anna and Red Hook Summer. He started writing and directing his own autobiographical plays and premiering them in New York. He got Tony and Olivier award nominations for his starring role in The Scottsboro Boys and filled a replacement role as Billy Flynn in Chicago, the longest-running revival on Broadway. By 2015, when he became a regular on the eight-series TV show Fear the Walking Dead, Domingo was a shapeshifter, able to move across formats without compromising the immediacy of his emotional depth. “People keep asking me when I’m coming back to the theatre, because I haven’t been on stage in 12 years now,” he says. “But I understand theatre already. I understand stagecraft and how to make it. And in many ways I’ve already made it – as an actor, director, writer and producer. I feel like I’m still trying to unlock how to create film and television. I just want to keep going where the challenges are.”

Today, the challenge is more related to getting comfortable in the driver’s seat and enjoying the newfound luxuries of being the leading man. The 2024 best actor Oscar nomination for his lead role in Rustin – playing the queer civil rights activist Bayard Rustin – was seminal for Domingo, a kind of christening that opened a world of possibilities. When he worked on Sing Sing it was a collaborative process with the director and co-writer. “I’ve made a lot of my own work in the theatre, but I’d never been presented with that sort of opportunity,” Domingo says. “I’ve never felt like I was given permission to make anything. But with this I was able to put my imprint on every frame of the film, and that felt so different and wonderful to me.” The way Domingo tells it, Sing Sing is one of the most meaningful projects of his career, and at least part of that is due to the film’s profit-sharing model, whereby everyone who worked on the movie, from the PAs to the director to Colman, gets the same wage and a stake in its earnings. “It’s not this big, shiny film, and it wasn’t really made to make money,” he says. “It was made because we wanted to examine these men in a different way, where, instead of being coarse and hardened and dangerous, they found space to be tender and joyful and playful.” When A24 acquired the theatrical rights, everybody got a cut.

More than 30 years after he started out, Hollywood has finally caught up with Colman Domingo. Now he’s in the midst of his own directorial outing: a biopic of Nat King Cole, about whom Domingo co-wrote a script for the stage in 2019. Cole is an American cultural icon Domingo is keen to deconstruct, and he’s curious to see if playing him in a film will make him hear the music any differently. “I’ve been building my own work for such a long time, and for [most of that] time it didn’t feel like this industry was checking for me at all,” he says. “But I never put any limitations on myself or decided that I should be in any particular lane. I’ve always done everything and never sold myself short. If nothing else, I’ll never allow anyone to limit me on what I can play or do. I’m always pivoting, always changing. All I want is to keep growing, to keep being challenged, to keep that spirit of openness and to always be willing to fall.” The industry, he says, is only just beginning to see him the way he has always seen himself.

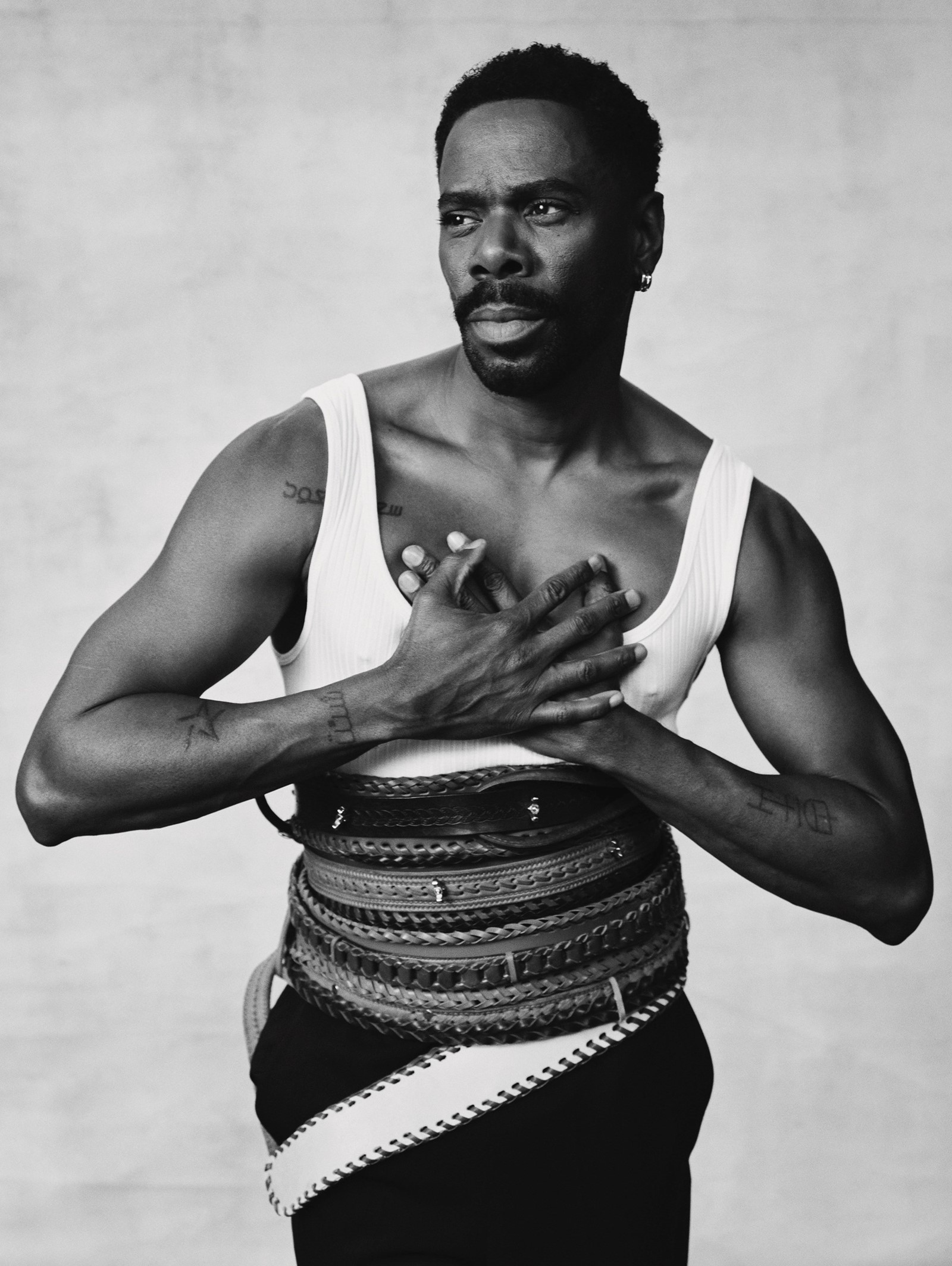

Grooming: Jessica Smalls at A-Frame Agency using DANESSA MYRICKS. Digital tech: Paul C Tucker. Photographic assistant: Mark Jayson Quines. Styling assistants: Gabriella George, Gregory Russill and Hanna Ahlgrim. Tailor: Leroy Gough at Lars Nord. Production: PRODn. Producers: Matthew McCann and Samantha Robles. Executive producer: Sarah Maxwell. Production assistants: Lindsey Gomez, Sasha Smithie and Daniel Weiner. Post-production: Picture House and The Small Darkroom. Special thanks to Seret Studios

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 6 March 2025. Pre-order here.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageJacket, shirt with frog collar fastening and trousers by VALENTINO. His own earrings. Stylist’s own vintage flower brooch. And gloves by VALENTINO GARAVANIPhotography by Rahim Fortune, Styling by Raphael Hirsch

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine:

I hear Colman Domingo before I see him – as I rise through the arteries of an old building in Brooklyn. His laughter, deep and low as thunder, spills into the hallway as the lift doors slide open.

Next is his face – a sensitive, moustached, elastic face that morphs easily into that of a loving father (If Beale Street Could Talk), or snarling pimp (Zola), or abusive, capricious husband (The Color Purple), or incarcerated thespian drunk on hope and performance (Sing Sing).

The studio in Greenpoint is all brick walls and wooden beams, with large windows that overlook the stormy East River and the diorama of Manhattan unfurling just beyond it. In 2001, following a decade as a fêted stage actor in San Francisco, Domingo moved to New York. He lived there for 16 years – because he is obsessed with reinvention and where better to remake yourself offstage than in a city that doesn’t care who or what you are, and in a rent-stabilized building that is affectionately known as the Home for Wayward Actors? Today, it seems impossible to imagine Domingo as anything other than an entertainer. I find him between shots, gliding across the wooden floors, humming and snapping to Marvin Gaye. (In A Boy and His Soul, a play Domingo wrote and starred in in 2009, long before Hollywood took notice of him, the actor referred to Gaye’s voice as “the sound of my heart, my feet, my eyes”.) He’s also making casual conversation with the crew, gesticulating in wide arcs as he speaks and dispensing from a silver tray small vanilla cupcakes, each printed with a photograph of him aged seven or eight, wearing a yellow top with a big Seventies collar and a gleeful, unselfconscious smile that’s missing a couple of teeth.

He offers a large hand for me to shake. “I’m Colman.” He is 6ft 2in and possessed of a theatre kid’s physicality and the sort of imposing vintage grandeur that holds the room. He is gregarious, though he was quite shy as a child, he says, and does not break eye contact in conversation. That laugh comes often and easily. Domingo wears clothes with flair. He is co-chairing this year’s Met Gala, where the theme will be Superfine: Tailoring Black Style. He is a Sagittarius, which perhaps goes some way towards explaining the edible childhood photos he’s imploring the crew to consume: his 55th birthday is in two days, on Thanksgiving, and the cakes are a gag gift from his team.

“Everyone expects me to throw this big party,” he says. It’s not an unfair assumption, since Domingo likes to dance, likes to sing. His friend the actor Natasha Lyonne once described him as having “bring the party” energy. But 2024 offered a sustained period of festivities, disco balls and red carpet appearances, which means that all Domingo wants to do now is go on an early-morning hike in Malibu, have dinner with some friends at their place, watch some television. “I just want to take it easy, because I feel like it’s been such an enormous year,” he says.

Since the autumn of 2023, Domingo has been on a tear. Rustin, The Color Purple, Sing Sing, Drive-Away Dolls … He spent several months in Toronto filming The Madness, which is, at the time of writing, the most popular television show on Netflix, and found time to contribute voice roles to a sci-fi adventure movie for the Russo brothers (The Electric State) and a forthcoming Spiderman series for Disney+. He’s starring in the biopic Michael, set to be released in the autumn, as the singer-songwriter’s father, Joe Jackson; he’s working on a comedy series (The Four Seasons) alongside Steve Carell and Tina Fey; and he’s appearing in an untitled Spielberg film with Emily Blunt, Colin Firth and Josh O’Connor, though he refuses to reveal any of the specifics. Along the way he has become a critical darling, picking up best actor nominations at the Oscars and Baftas, two Golden Globe nominations and Gotham Award wins, four NAACP Image Awards, an Emmy win for his role in Euphoria – and too many acknowledgments from various critics’ societies to mention here.

Turning 55, Domingo has arrived at a place he would never have imagined, despite more than three decades of acting. For years now he’s been a leading man trapped under the skin of a character actor, the guy directors would call on to add texture and feeling and his ferocious, trademark empathy to their projects. “I’ve always been the support – like, the one who took care of the soul of the company, and people depended on me for that,” Domingo says. But it seemed clear nonetheless, across dozens of films, that he had his own field of gravity. “I’m very aware that I’m having a glorious moment in this industry. And I don’t know how long that time will last. But I do feel like I’ve got the building blocks for it. Hopefully I can keep evolving and have a good time with it, because not everyone does. People always ask me if I’m enjoying the attention – and I absolutely am. Maybe it’s because it’s happened so late in my career that I don’t have those same complicated feelings about fame and success.” There’s still the weirdness of having to be on all the time and the knowledge that moving into the spotlight means sacrificing privacy and renegotiating boundaries. “But I feel really happy about this moment. And I say this without ego – I know that I took all the steps to get here and did all the hard work. None of it was handed to me. It wasn’t because I was lucky or because I was pretty. It’s because I took it. It’s because I had to take it.”

***

“I’m very aware that I’m having a glorious moment in this industry … Hopefully I can keep evolving and have a good time with it, because not everyone does” – Colman Domingo

In Sing Sing, Domingo plays (the real life) John “Divine G” Whitfield. He’s a literary sensation at the maximum-security prison in New York state. The drab, mass-produced uniforms and routine denial of his humanity have not obliterated his sense of self. There is still a human soul to bruise and buoyancy to puncture. Divine G is serving a sentence of 25 years to life for a crime he did not commit and he passes the interminable time by studying the law, helping other inmates with their cases and writing plays and novels, which he performs as a founding member of a theatre programme, Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) – a transformative non-profit organisation launched at Sing Sing in 1996 that runs in various New York state prisons to this day. He’s an anchor in the sanctum of the RTA, a deferential leader his peers look to for guidance and sometimes material. Domingo plays it gracefully, occasionally stripping back a veneer of poise to reveal a flash of self-importance, indignation, or annihilating despair; he relishes these moments, when the mask falls away to reveal the fullness of the person behind it.

As Sing Sing crescendoes, so too does the anguish of its protagonist. The centre – that hope, the sunniness that protects against the slow crawl of dread – cannot hold. There’s the way he’s the last person to disrobe and return to his prison uniform after the Shakespeare performance that opens the film. There is the slight disgruntlement in his frame when the other group members choose to do a wacky, nonsensical, time-travelling comedy over his own latest drama. There is the further deflation of his pride when he realises that one of his new peers, the rough and unpredictable Divine Eye (the brilliant Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin playing a version of himself), is auditioning to play Hamlet, a role that Divine G seems to believe is his birthright. And there is the way his face is drained of all its light when he realises just how stuck he is, that he will not be getting out soon or maybe ever, that all his dogged efforts to prove his innocence have meant nothing. “It’s a way for these men to get some rehabilitation and to get in touch with their feelings,” he explains of the RTA in a clemency hearing where his right to freedom is being considered. “And are you acting right now?” asks the sharp woman who will deny him it. The disbelief creases his forehead and parts his lips. The horror wets his eyes. Just a few scenes later he will fall apart completely – on stage, spit flying out of his mouth, tears now streaming down his face, his body tense and suddenly dangerous.

Domingo is expert at slowly reaching such emotional extremes. He can play it hard, can play it tough as nails, but as his character warns Divine Eye as he prepares for his role as Hamlet: “Anger is the easiest thing to play. What’s more complicated is to play hurt.” Domingo’s repertoire is punctuated with the occasional show of woundedness, but his performance as Divine G feels like the deepest cut. The first time he watched the movie back, it “wrecked” him. “It feels like the most vulnerable version of me is on that screen, this raw version without any polish at all,” he says. Part of this is a credit to his castmates, most of whom are former inmates who went through this programme themselves; the candour and realness of their performances, particularly Maclin’s eruptions of hostility, forced him to reach down into himself and produce something honest. “I grew up in inner-city West Philadelphia, so I know these guys – these men trapped in these institutions who nobody thinks about any more and who never had a chance,” he says. The other part is logistical: where most Hollywood studio films can take anywhere from 30 to 160 days to film, Sing Sing was shot in just 19, in the window Domingo had between finishing The Color Purple and doing pick-up shots for Rustin. “I think I brought more of myself into it,” he says, “because I didn’t have the time to prepare or be sure about anything.”

Typically, research is his favourite part of the process. “I wouldn’t say that I over prepare,” Domingo says. “But by the time I get to a set I’ve usually had four months of researching the details, making all these private decisions that nobody but me would know or care about. Like, how does this character move his hands? Is he comfortable with looking people in the eye? How does he have sex? How has he been hurt?” It was his decision to make his character’s uniform a touch too short, to suggest that it was issued a long time ago, long enough that Divine G had outgrown it. Before he was an actor, Domingo wanted to be a photojournalist; that he builds each character from a well of questions makes sense: “I need to download all of that information so that I can make a real, whole person and not someone who just fits the beats of the script.”

Take X, his violent, menacing pimp in Janicza Bravo’s Zola. In part because of sex worker Stefani’s willed unreliability, the viewer has very little context for him, no sense of who he is or where he came from or why he’s accompanying her and Zola on a trip to Florida. We don’t even have access to his real name until the film is almost done – all we know is he “takes care” of Stefani, a euphemistic term that Zola easily decodes. Domingo, alighting on these methods of deception and manipulation, elaborates the mystery. Sometimes, amid an exasperated fugue, his voice drops a register and his accent veers Nigerian. The effect of the sudden switch is jarring. “I decided that he was an immigrant who wants what everyone else seems to have, which is the American dream, but he doesn’t have access to it,” Domingo says. “He doesn’t have papers. But he does know women.” His interest in the humanity of the character led him to research the psychology of sex trafficking, to better understand the mechanisms of domination involved. That’s why he gave X that strange and comedic habit of coughing loudly when he’s peeing in the bathroom with the door open. “It’s this other way he has of trying to maintain control, by asserting his presence even when he’s in another room.”

“Eventually I realised that being a journalism major or being an actor, writer and director were all animated by the same desire, which is to understand other people” – Colman Domingo

Much like his character in Sing Sing – a movie about acting as a means of accessing humanity as opposed to artifice – Domingo believes his craft is a tool of empathy. His performances are always searching for tenderness, even, or perhaps especially, when the character feels beyond redemption. “I’m interested in fragility,” Domingo says. Playing Mister in The Color Purple was another way to study the psychology of abuse and to anatomise how violence ricochets. The villain is broken in his own way. “If I can get to the core of that, it’ll complicate him, and the audience’s empathy, because you’re forced to see the ways he’s also human,” he says. “I have to find the humanity in everyone. There’s always more behind the eyes.”

Which was part of the impetus for deciding to play Joe Jackson, a man known mostly by the public as a cartoonish representation of evil: he allegedly beat his children with cords and belt buckles, isolated them from other kids, forced them to call him Joseph (never Dad) and rehearse for hours on end, and is reported to have ridiculed Michael so incessantly about the size of his nose that the star surgically disfigured himself beyond recognition. “I’m very curious about characters who are complex and may have already been tried in the court of public opinion,” Domingo says. “Everybody has an opinion about Joe Jackson. The reason I wanted to interrogate his part of the story in this biopic is that I want to understand this man who created one of the most incredible artists of our lifetime. I want to deconstruct him. Everybody says he was a tough man, that he was just really hard. But why was he like that? Why did he have to be that way?“

“I think as an actor, we have to find that place of knowing a lot, and then unknowing it,” he continues. Without the possibility of discovery, the character remains static and bloodless, without revelation. “Everything about this career is about understanding psychology, understanding people. Everyone wants something – if you can figure out what that is, then you understand the person. In that way, acting is a bit like flirting.” You can get to the root of desire.

***

Domingo’s mother worked for a bank and her husband sanded floors. He was raised the third of four children in a home that was filled with soul music: Marvin Gaye again, the Isley Brothers, Teddy Pendergrass, Earth, Wind & Fire. Always there was the crackle of vinyl, the smouldering slow jams over the radio airwaves. Really, Domingo was more likely to be a musician than an actor, although he never really set out to be either (aside from some violin lessons). His mother, Edith, after whom he named the production company he runs with his husband, Raúl, was much looser in how she raised him and his younger brother than how she cared for his older siblings, whom he describes as “salt of the earth” people. “They grew up with this sense that you’re supposed to get older, find a good job somewhere and then get married and start a family,” he says. “But with us she encouraged us to do whatever made us happy, to be joyful and to be of service to others, whatever form that might take.”

In high school, he wore his older siblings’ hand-me-downs and did his best not to be seen. He didn’t speak much, trying to ensure he wasn’t beaten up. He says most of the people from that time would have been surprised by the career he has now – he preferred to be invisible, was more comfortable with observing than being observed. People wouldn’t know that he was gay if they couldn’t see him, if he kept quiet. He studied journalism at Temple University, in Philadelphia, and envisioned himself travelling to war-torn countries and documenting atrocities. He took portraits of actors as a side hustle. When he was selecting the courses for his first year, his mother encouraged him to take at least one class just for fun and he ended up on an introduction to acting course that helped him conquer any shyness. “It got me outside of myself and allowed me to try out different personalities and ways of being,” he says. Halfway through his first term, his teacher approached him and asked whether he’d ever considered acting as a profession. “I was 19 years old and he said to me, ‘I think you have a gift,’” he says. “That shook my whole foundation, because I think it was the first time anyone had ever said something like that to me.”

He started taking classes off-campus at the Walnut Street Theatre in his second year. “I was very shy about telling anybody what I was doing, because I was a little bit embarrassed and because being an actor felt special,” Domingo says. “It was just for me to enjoy and I didn’t want anybody to take it away from me or tell me I wasn’t worthy and couldn’t do it.” When he was 21, some friends who had moved to San Francisco invited him to stay with them and he accepted. He imagined it was a chance for him to become a whole, free person, an opportunity to begin a Big Life in a famously gay city. Though he planned to go only for a month or so, he stayed for ten years. “I lived in a studio apartment with three other guys, and it was so tight that my bedroom was a walk-in closet,” he says. (The metaphor is almost too obvious, although he came out to his family around this time.) He got a job bartending at a club that was next to a church and recognised the conversations with patrons as rich artistic material. To be the bartender was to play a role too, to be tasked with identifying what people want or need and meeting them there. Anyone could come through the bar doors, their heads filled with all sorts of strange thoughts. “Eventually I realised that being a journalism major or being an actor, writer and director were all animated by the same desire, which is to understand other people,” he says.

“I’ve always done everything and never sold myself short. If nothing else, I’ll never allow anyone to limit me on what I can play or do” – Colman Domingo

In San Francisco, he had all kinds of jobs: working in customer service at Macy’s, performing in a circus. On the side, he read Stanislavski and Uta Hagen and went to auditions. “I’ve never attached the word ‘struggle’ to my journey,” he says. “I thought, if one day you’re acting, the next day you’re bartending, the next you’re doing a temp job or teaching or doing a reading – I considered that to be the life of an artist.” He loved bartending, getting to know people and making cocktails and taking care of the bar. He felt liberated, like his life was exciting.

The first audition he booked was for an educational play called The Inner Circle, in which he played a high school student who receives a blood transfusion and becomes HIV positive. Gradually, he booked more work. He fell in love with Shakespeare. He acted in more plays. He did television shows. “I became a Bay Area theatre actor and sort of rose to the top of San Francisco,” he says.

But Domingo wanted to push himself as an artist, and in New York he expanded. He acted on TV and was luminous on stage. In 2007, he starred as a Dutch nudist, closeted choir director and German performance artist in a rock musical called Passing Strange, which opened on Broadway the year after its successful run at the city’s Public Theater. It earned him an Obie Award and the attention of Spike Lee, who filmed the play and later cast Domingo in his movies Miracle at St Anna and Red Hook Summer. He started writing and directing his own autobiographical plays and premiering them in New York. He got Tony and Olivier award nominations for his starring role in The Scottsboro Boys and filled a replacement role as Billy Flynn in Chicago, the longest-running revival on Broadway. By 2015, when he became a regular on the eight-series TV show Fear the Walking Dead, Domingo was a shapeshifter, able to move across formats without compromising the immediacy of his emotional depth. “People keep asking me when I’m coming back to the theatre, because I haven’t been on stage in 12 years now,” he says. “But I understand theatre already. I understand stagecraft and how to make it. And in many ways I’ve already made it – as an actor, director, writer and producer. I feel like I’m still trying to unlock how to create film and television. I just want to keep going where the challenges are.”

Today, the challenge is more related to getting comfortable in the driver’s seat and enjoying the newfound luxuries of being the leading man. The 2024 best actor Oscar nomination for his lead role in Rustin – playing the queer civil rights activist Bayard Rustin – was seminal for Domingo, a kind of christening that opened a world of possibilities. When he worked on Sing Sing it was a collaborative process with the director and co-writer. “I’ve made a lot of my own work in the theatre, but I’d never been presented with that sort of opportunity,” Domingo says. “I’ve never felt like I was given permission to make anything. But with this I was able to put my imprint on every frame of the film, and that felt so different and wonderful to me.” The way Domingo tells it, Sing Sing is one of the most meaningful projects of his career, and at least part of that is due to the film’s profit-sharing model, whereby everyone who worked on the movie, from the PAs to the director to Colman, gets the same wage and a stake in its earnings. “It’s not this big, shiny film, and it wasn’t really made to make money,” he says. “It was made because we wanted to examine these men in a different way, where, instead of being coarse and hardened and dangerous, they found space to be tender and joyful and playful.” When A24 acquired the theatrical rights, everybody got a cut.

More than 30 years after he started out, Hollywood has finally caught up with Colman Domingo. Now he’s in the midst of his own directorial outing: a biopic of Nat King Cole, about whom Domingo co-wrote a script for the stage in 2019. Cole is an American cultural icon Domingo is keen to deconstruct, and he’s curious to see if playing him in a film will make him hear the music any differently. “I’ve been building my own work for such a long time, and for [most of that] time it didn’t feel like this industry was checking for me at all,” he says. “But I never put any limitations on myself or decided that I should be in any particular lane. I’ve always done everything and never sold myself short. If nothing else, I’ll never allow anyone to limit me on what I can play or do. I’m always pivoting, always changing. All I want is to keep growing, to keep being challenged, to keep that spirit of openness and to always be willing to fall.” The industry, he says, is only just beginning to see him the way he has always seen himself.

Grooming: Jessica Smalls at A-Frame Agency using DANESSA MYRICKS. Digital tech: Paul C Tucker. Photographic assistant: Mark Jayson Quines. Styling assistants: Gabriella George, Gregory Russill and Hanna Ahlgrim. Tailor: Leroy Gough at Lars Nord. Production: PRODn. Producers: Matthew McCann and Samantha Robles. Executive producer: Sarah Maxwell. Production assistants: Lindsey Gomez, Sasha Smithie and Daniel Weiner. Post-production: Picture House and The Small Darkroom. Special thanks to Seret Studios

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 6 March 2025. Pre-order here.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.