Rewrite

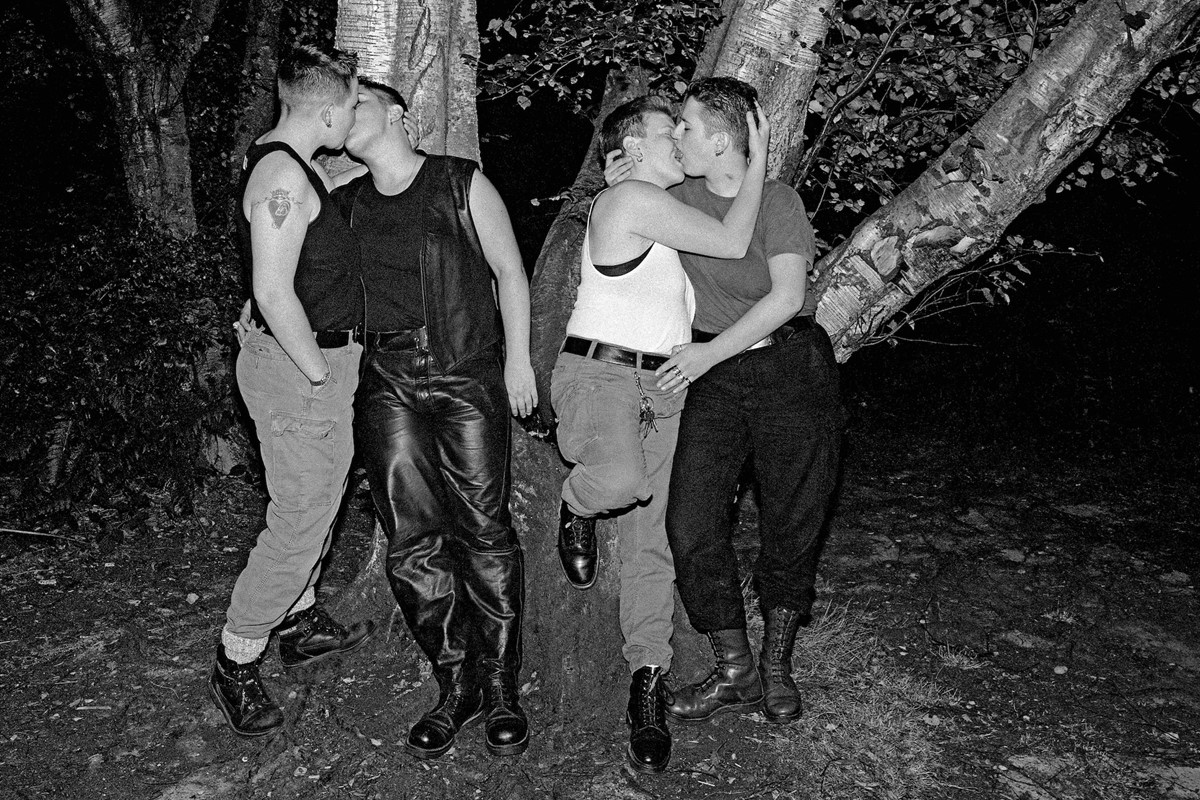

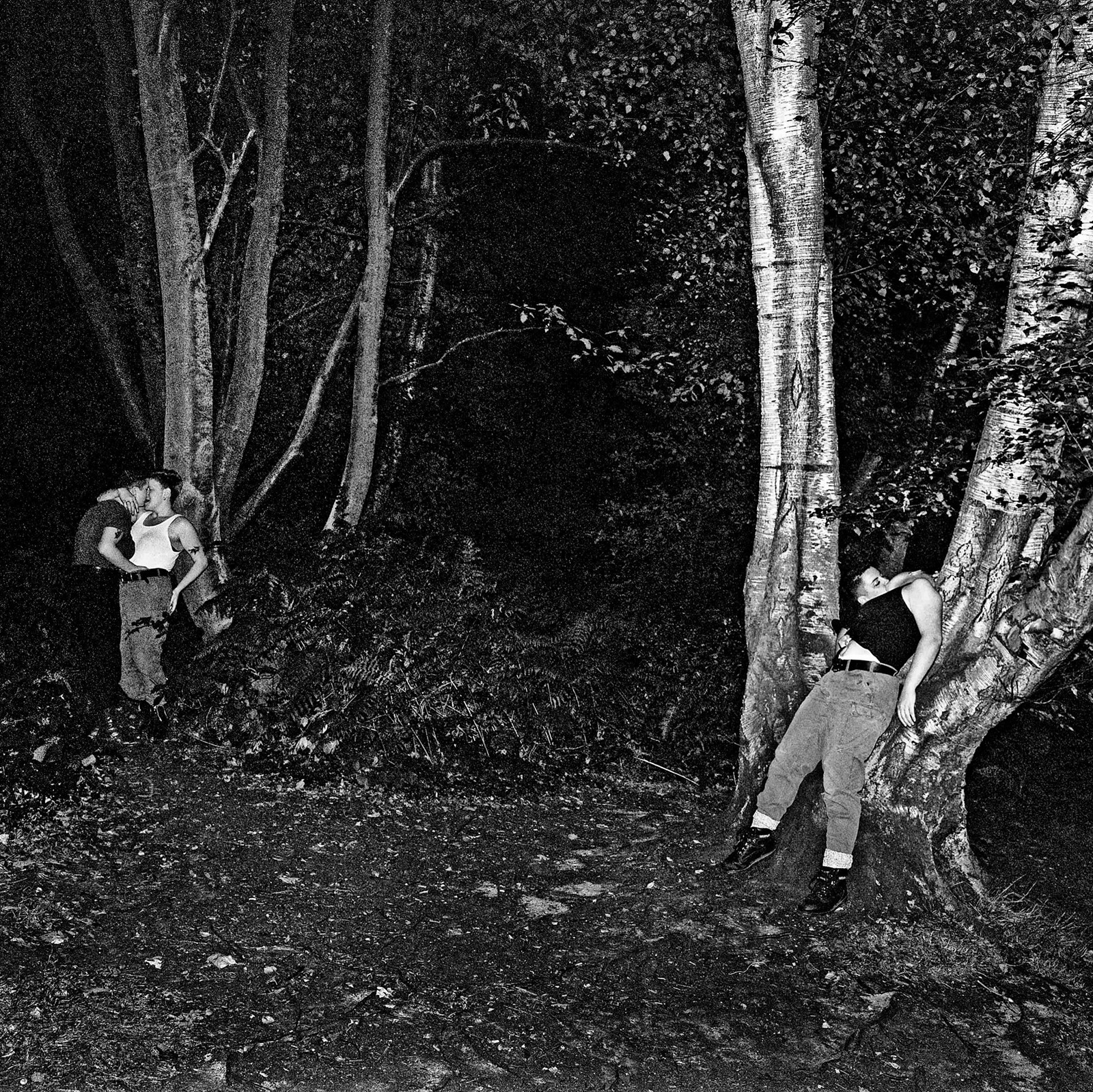

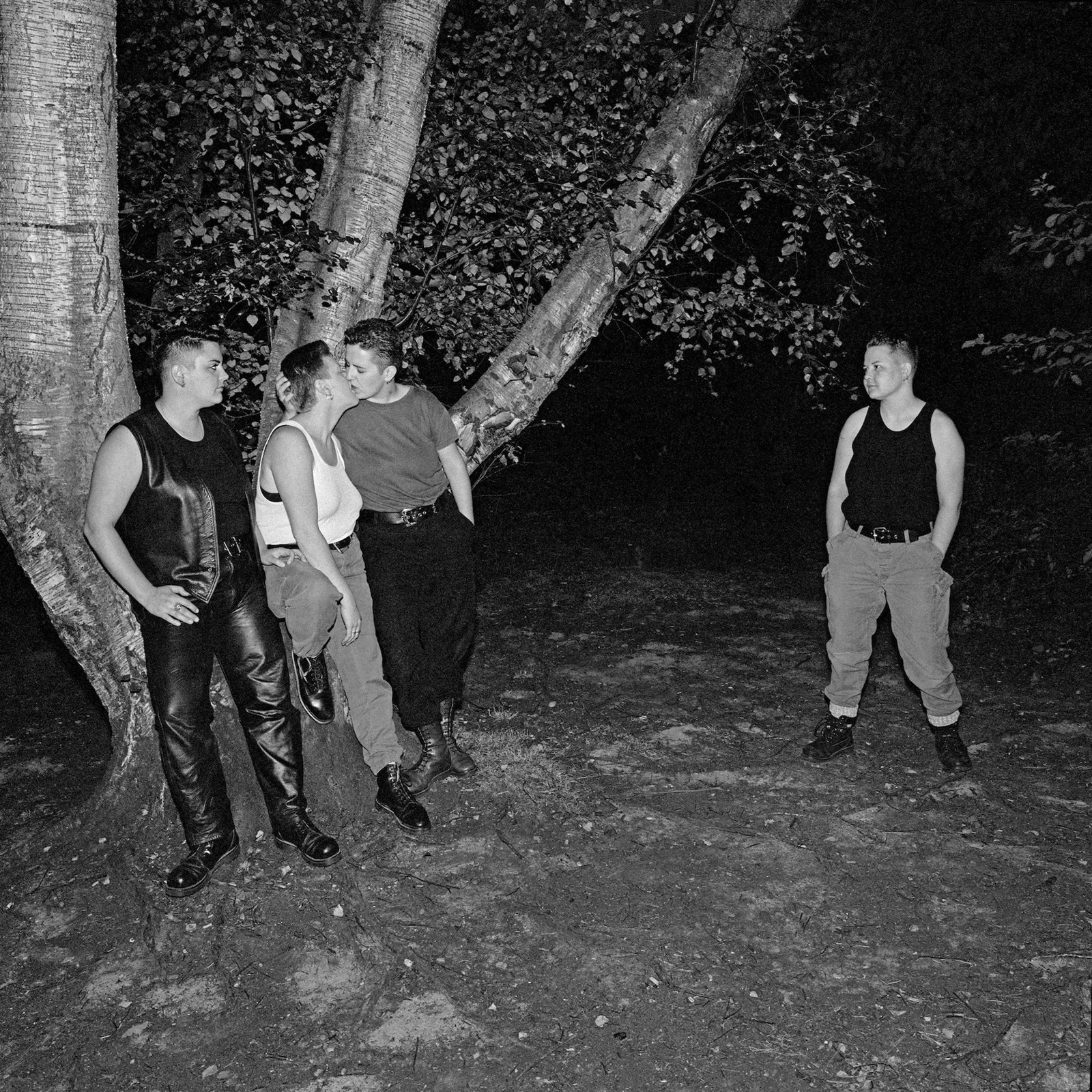

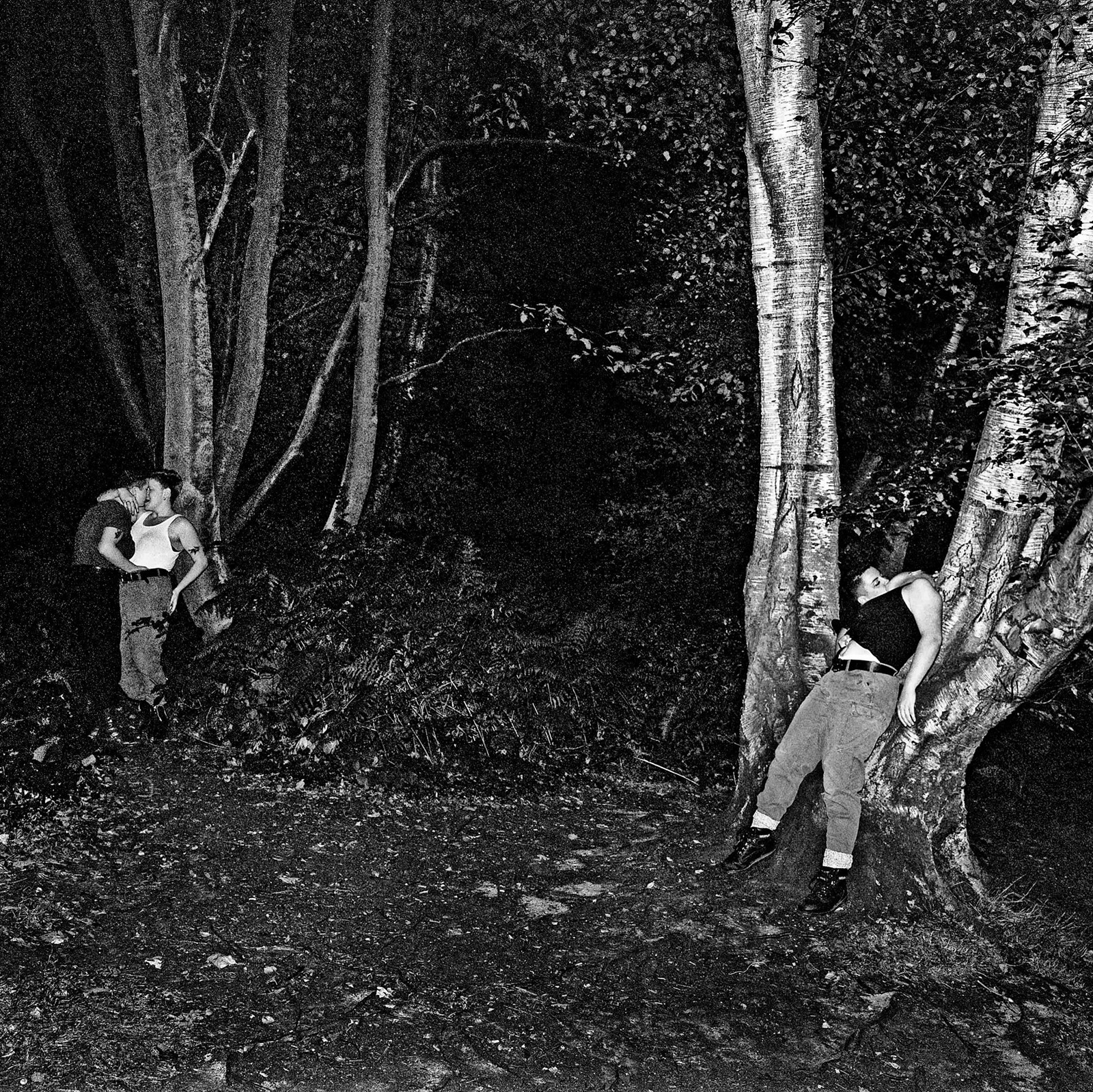

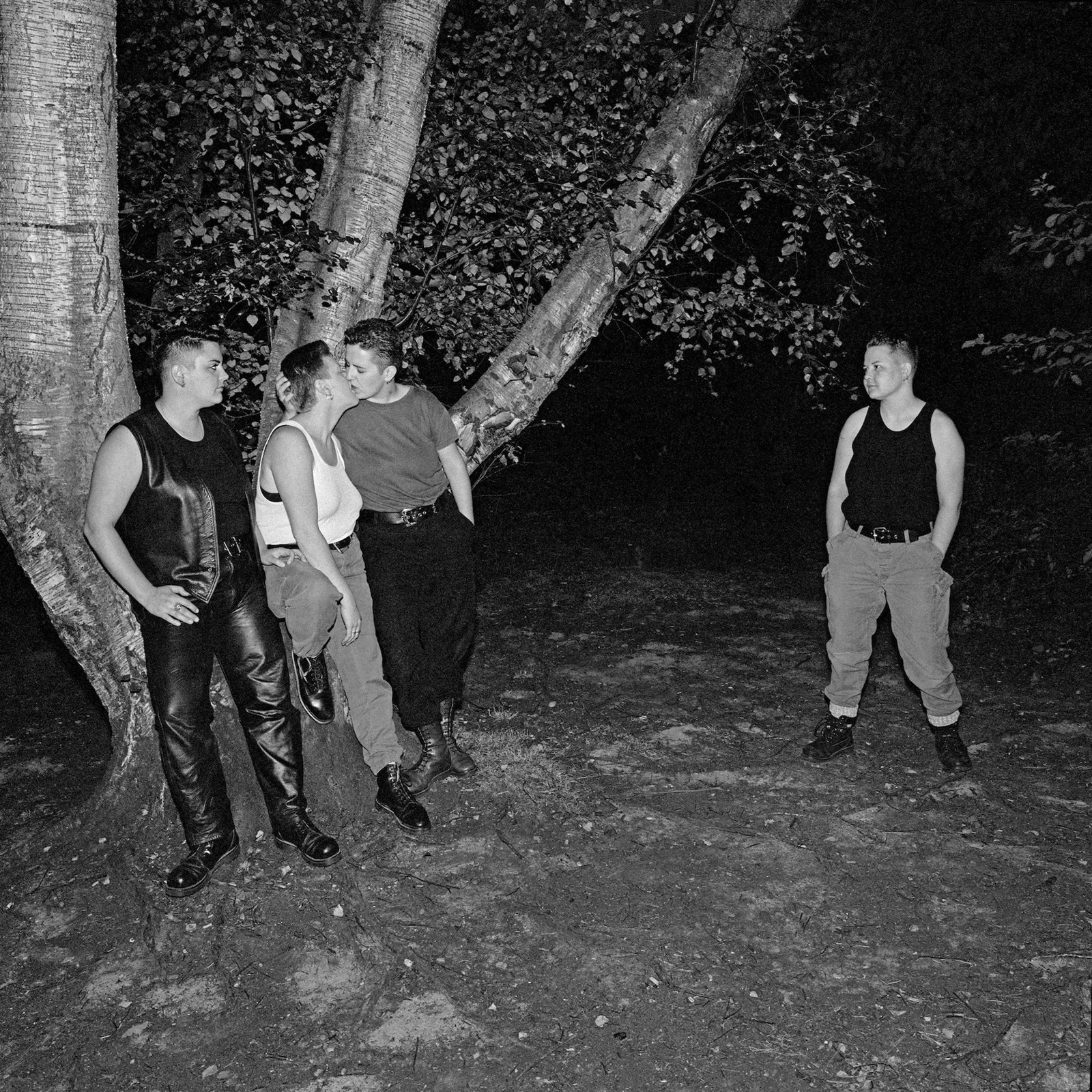

Lead ImagePhotography byDel LaGrace Volcano. Courtesy of Climax Books

Photographer Del LaGrace Volcano can’t remember the precise date of the evening they trudged out into the darkness on Hampstead Heath with friends to create the images in Queer Dyke Cruising. It was a heady time; Volcano was living in short-life communal housing, busy photographing S&M dykes at the collectively run sex and performance club Chain Reaction in Vauxhall, and attending protests against Section 28, Margaret Thatcher’s anti-gay law that arose as a homophobic response to the HIV/Aids crisis.

This was the historic backdrop to Queer Dyke Cruising – a time when lesbian culture was firmly outside the mainstream. To see the photos of dykes fumbling against trees, rolling around in the grass, and making out in Dr Martens and dresses as dawn breaks, all the while laughing about it, was a visual statement of rebellion. So too was the fact that the dykes pictured are playing at cruising – searching for or having casual sex with strangers – a practice usually the terrain of gay men. Here, the photos seem to make a secondary statement: AFAB people may have fewer bars, clubs and well-trodden cruising grounds to go to, but can’t we claim these places for ourselves?

After the photos were shown at Tate’s group show Women In Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990 last year, London publisher Climax Books is now issuing Queer Dyke Cruising as a dedicated photo book for the first time. When I spoke to Volcano about the story behind the photographs, they asked why I think Climax might have been interested in these particular photos, and why now. I mutter something about the blossoming of deliberate attempts to foster sexy and playful femme dyke, masc dyke, and transmasc-inclusive parties across cities like London and Berlin today. Perhaps Volcano’s images can provide further motivation to explore FLINTA sex spaces, only out in the open, to unleash ourselves on public space.

Below, Del LaGrace Volcano tells the story behind Queer Dyke Cruising.

Amelia Abraham: The photos in Queer Dyke Cruising were shot around a historic cruising site, mostly for men. Was this somewhere you and other dykes went to cruise?

Del LaGrace Volcano: I had been there myself and a couple of gay friends took it upon themselves to educate me in all things cruising. When I went there alone I was more of a femme dyke. Even though I tried to butch it up, I was not successful. It was only once I let my beard grow that I had a modicum of success in Hampstead Heath.

I like making work out in the world, combining the urban or natural landscape with the artificial or constructed, where we perform for the camera, for each other, and for the sheer pleasure of being seen on our own terms. In the Hampstead Heath pictures, I was out with two dyke couples who might have been poly but the session was semi-staged, not like the film Pansexual Public Porn (1997), made in the same location later, where people having sex in the woods with strangers spontaneously happened.

AA: I was interested to read in the text in Queer Dyke Cruising that you cruised yourself when you were younger.

DLV: I didn’t think of it as cruising back then but it was similar in the sense that fear of the unknowable was an ever-present factor. Looking back today, I actually find it somewhat hard to understand what was driving me to do all the super kinky things I did.

“Women having casual sex or sex in public are positioned as ‘sluts’ or drunk. How often do you hear a woman say: ‘I have to go out and get fucked now’?” – Del LaGrace Volcano

AA: You mention “stranger danger” to describe compulsive risky sex. I relate. On some subconscious level, maybe it was wanting to have a right to that as an AFAB person.

DLV: I think there’s some truth to that for me, but I also now know I have a rogue Y chromosome flying around. Could that have any determining effect on my behaviour? It wasn’t like, “I’m doing this for political reasons! No one’s going to stop me!” It was a bodily thing. I talk to gay male friends about how cruising feels dangerous and that’s part of the attraction to the whole practice. I know I’m not the only person AFAB who goes out and does this stuff. But being AFAB is often cast in a way that gives you less agency. For example, women having casual sex or sex in public are positioned as “sluts” or drunk. How often do you hear a woman say: “I have to go out and get fucked now”? That comes back to the role play in these images. Roleplaying is a way of permitting oneself to step away from regulation and social control, something we all need at times.

AA: How do you think the context between when these images were first made and now has changed or not changed, in terms of cultural ideas around sex?

DLV: They’ve definitely changed. I don’t want to put it in terms of some hackneyed progress narrative at all, but cruising isn’t specifically criminalised anymore, depending on where you do it. It’s something more queer people have seen as part of our cultural heritage, whether you’ve done it or not. Especially given the British history of Oscar Wilde and many others who were damaged by policing and anti-gay laws. It’s not illegal but it still has that edge because it was illegal.

AA: As Dominic Johnson writes in the book: “Cruising lets us get off, but it also sends a message: we queers are killable, by hatred, violence and disease – but our culture is not.”

DLV: Right. And I’m sure they exist, but I do not know of an archive of AFAB people cruising, or other people who have taken those kinds of photos. Do you?

AA: Maybe Jill Posener’s sexier photos, or Phyllis Christopher’s photos of lesbian dark rooms. Interestingly, you all spent time in San Francisco. How did living between San Francisco and London in the 80s inform your photography?

DLV: It was at Scott’s Bar (a working class dyke bar in San Francisco) where I first started making dyke work. I had also joined the first lesbian S&M group Samois in San Francisco, and was ecstatic to learn a new way of talking about sex and desire. But then I fell deeply in love with a British lesbian separatist and decided to move to London in 1982, to a separatist housing collective called Hurricane in Ladbroke Grove. I renounced S&M and for six months I spoke to no men!

When I returned to London in October 1987 everything seemed very different. In London I found I had more time – so many of us were on the dole and living in ways that aren’t possible now. By sheer kismet, I ended up living in the shared flat where the north London branch of the Chain Reaction collective met to plot. I knew I was in the perfect place to continue making work about the culture I was part of, the culture the images helped to create.

Also, in San Francisco, so many people were dying because of HIV/Aids. I was quite traumatised by losing friends and taking certain photos seemed crass. In the UK there was a slightly different atmosphere. Perhaps people were not realising how serious the Aids crisis would become. In the UK, my photos felt more like a form of resistance, and there was a distance for me from the grief of losing close friends and lovers.

AA: We often talk about work that was made in response to HIV/Aids, not the work that wasn’t made because people were unwell or grieving. When you look at these images, there’s a kind of haunting reading, seeing these AFAB people enacting past encounters.

DLV: My first thought was that was a way of being in touch with them or bringing them back. They’re also not documentary photographs. I don’t think you’d have had permission to go down to Hampstead Heath and shoot “real” men cruising either. What’s extraordinary about these cruising photos is they’re staged but they’re also real experiences. I want to create a safe space for people to perform their fantasies. That’s what Queer Dyke Cruising was – a performance of a fantasy.

AA: How does the camera interact with the eroticism of the act itself? Did you find it hot shooting them? Did the people find it hot being in them?

DLV: I’ve written about photography in the context of a lesbian S&M relationship where I accept the position of the top. Therefore it is my job to create a safe space where magic can happen. My own pleasure is absolutely intertwined with theirs. Although I must confess that there have been times when those in front of the camera create their own path and I’m along for the ride. That’s beautiful too. It’s always part improv and part intention.

AA: Before our call, you asked why these photos might be interesting to people now. What do you think, or at least hope, in answer to that question?

DLV: I am really curious about how these images are going to land and where they will travel. The potential audience for this work goes beyond experience, both in generational terms and in many other ways I cannot begin to know. Let’s leave it as an open question.

Queer Dyke Cruising by Del LaGrace Volcano is published by Climax Books, and is out now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImagePhotography byDel LaGrace Volcano. Courtesy of Climax Books

Photographer Del LaGrace Volcano can’t remember the precise date of the evening they trudged out into the darkness on Hampstead Heath with friends to create the images in Queer Dyke Cruising. It was a heady time; Volcano was living in short-life communal housing, busy photographing S&M dykes at the collectively run sex and performance club Chain Reaction in Vauxhall, and attending protests against Section 28, Margaret Thatcher’s anti-gay law that arose as a homophobic response to the HIV/Aids crisis.

This was the historic backdrop to Queer Dyke Cruising – a time when lesbian culture was firmly outside the mainstream. To see the photos of dykes fumbling against trees, rolling around in the grass, and making out in Dr Martens and dresses as dawn breaks, all the while laughing about it, was a visual statement of rebellion. So too was the fact that the dykes pictured are playing at cruising – searching for or having casual sex with strangers – a practice usually the terrain of gay men. Here, the photos seem to make a secondary statement: AFAB people may have fewer bars, clubs and well-trodden cruising grounds to go to, but can’t we claim these places for ourselves?

After the photos were shown at Tate’s group show Women In Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990 last year, London publisher Climax Books is now issuing Queer Dyke Cruising as a dedicated photo book for the first time. When I spoke to Volcano about the story behind the photographs, they asked why I think Climax might have been interested in these particular photos, and why now. I mutter something about the blossoming of deliberate attempts to foster sexy and playful femme dyke, masc dyke, and transmasc-inclusive parties across cities like London and Berlin today. Perhaps Volcano’s images can provide further motivation to explore FLINTA sex spaces, only out in the open, to unleash ourselves on public space.

Below, Del LaGrace Volcano tells the story behind Queer Dyke Cruising.

Amelia Abraham: The photos in Queer Dyke Cruising were shot around a historic cruising site, mostly for men. Was this somewhere you and other dykes went to cruise?

Del LaGrace Volcano: I had been there myself and a couple of gay friends took it upon themselves to educate me in all things cruising. When I went there alone I was more of a femme dyke. Even though I tried to butch it up, I was not successful. It was only once I let my beard grow that I had a modicum of success in Hampstead Heath.

I like making work out in the world, combining the urban or natural landscape with the artificial or constructed, where we perform for the camera, for each other, and for the sheer pleasure of being seen on our own terms. In the Hampstead Heath pictures, I was out with two dyke couples who might have been poly but the session was semi-staged, not like the film Pansexual Public Porn (1997), made in the same location later, where people having sex in the woods with strangers spontaneously happened.

AA: I was interested to read in the text in Queer Dyke Cruising that you cruised yourself when you were younger.

DLV: I didn’t think of it as cruising back then but it was similar in the sense that fear of the unknowable was an ever-present factor. Looking back today, I actually find it somewhat hard to understand what was driving me to do all the super kinky things I did.

“Women having casual sex or sex in public are positioned as ‘sluts’ or drunk. How often do you hear a woman say: ‘I have to go out and get fucked now’?” – Del LaGrace Volcano

AA: You mention “stranger danger” to describe compulsive risky sex. I relate. On some subconscious level, maybe it was wanting to have a right to that as an AFAB person.

DLV: I think there’s some truth to that for me, but I also now know I have a rogue Y chromosome flying around. Could that have any determining effect on my behaviour? It wasn’t like, “I’m doing this for political reasons! No one’s going to stop me!” It was a bodily thing. I talk to gay male friends about how cruising feels dangerous and that’s part of the attraction to the whole practice. I know I’m not the only person AFAB who goes out and does this stuff. But being AFAB is often cast in a way that gives you less agency. For example, women having casual sex or sex in public are positioned as “sluts” or drunk. How often do you hear a woman say: “I have to go out and get fucked now”? That comes back to the role play in these images. Roleplaying is a way of permitting oneself to step away from regulation and social control, something we all need at times.

AA: How do you think the context between when these images were first made and now has changed or not changed, in terms of cultural ideas around sex?

DLV: They’ve definitely changed. I don’t want to put it in terms of some hackneyed progress narrative at all, but cruising isn’t specifically criminalised anymore, depending on where you do it. It’s something more queer people have seen as part of our cultural heritage, whether you’ve done it or not. Especially given the British history of Oscar Wilde and many others who were damaged by policing and anti-gay laws. It’s not illegal but it still has that edge because it was illegal.

AA: As Dominic Johnson writes in the book: “Cruising lets us get off, but it also sends a message: we queers are killable, by hatred, violence and disease – but our culture is not.”

DLV: Right. And I’m sure they exist, but I do not know of an archive of AFAB people cruising, or other people who have taken those kinds of photos. Do you?

AA: Maybe Jill Posener’s sexier photos, or Phyllis Christopher’s photos of lesbian dark rooms. Interestingly, you all spent time in San Francisco. How did living between San Francisco and London in the 80s inform your photography?

DLV: It was at Scott’s Bar (a working class dyke bar in San Francisco) where I first started making dyke work. I had also joined the first lesbian S&M group Samois in San Francisco, and was ecstatic to learn a new way of talking about sex and desire. But then I fell deeply in love with a British lesbian separatist and decided to move to London in 1982, to a separatist housing collective called Hurricane in Ladbroke Grove. I renounced S&M and for six months I spoke to no men!

When I returned to London in October 1987 everything seemed very different. In London I found I had more time – so many of us were on the dole and living in ways that aren’t possible now. By sheer kismet, I ended up living in the shared flat where the north London branch of the Chain Reaction collective met to plot. I knew I was in the perfect place to continue making work about the culture I was part of, the culture the images helped to create.

Also, in San Francisco, so many people were dying because of HIV/Aids. I was quite traumatised by losing friends and taking certain photos seemed crass. In the UK there was a slightly different atmosphere. Perhaps people were not realising how serious the Aids crisis would become. In the UK, my photos felt more like a form of resistance, and there was a distance for me from the grief of losing close friends and lovers.

AA: We often talk about work that was made in response to HIV/Aids, not the work that wasn’t made because people were unwell or grieving. When you look at these images, there’s a kind of haunting reading, seeing these AFAB people enacting past encounters.

DLV: My first thought was that was a way of being in touch with them or bringing them back. They’re also not documentary photographs. I don’t think you’d have had permission to go down to Hampstead Heath and shoot “real” men cruising either. What’s extraordinary about these cruising photos is they’re staged but they’re also real experiences. I want to create a safe space for people to perform their fantasies. That’s what Queer Dyke Cruising was – a performance of a fantasy.

AA: How does the camera interact with the eroticism of the act itself? Did you find it hot shooting them? Did the people find it hot being in them?

DLV: I’ve written about photography in the context of a lesbian S&M relationship where I accept the position of the top. Therefore it is my job to create a safe space where magic can happen. My own pleasure is absolutely intertwined with theirs. Although I must confess that there have been times when those in front of the camera create their own path and I’m along for the ride. That’s beautiful too. It’s always part improv and part intention.

AA: Before our call, you asked why these photos might be interesting to people now. What do you think, or at least hope, in answer to that question?

DLV: I am really curious about how these images are going to land and where they will travel. The potential audience for this work goes beyond experience, both in generational terms and in many other ways I cannot begin to know. Let’s leave it as an open question.

Queer Dyke Cruising by Del LaGrace Volcano is published by Climax Books, and is out now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.