Rewrite

A slice-of-life look at early ’80s NYC, cult classic Wild Style is the endlessly sampled snapshot of an exciting underground movement in its infancy. Over 30 years later, independent filmmaker Charlie Ahearn breaks down the original hip-hop feature in a Wonderland exclusive.

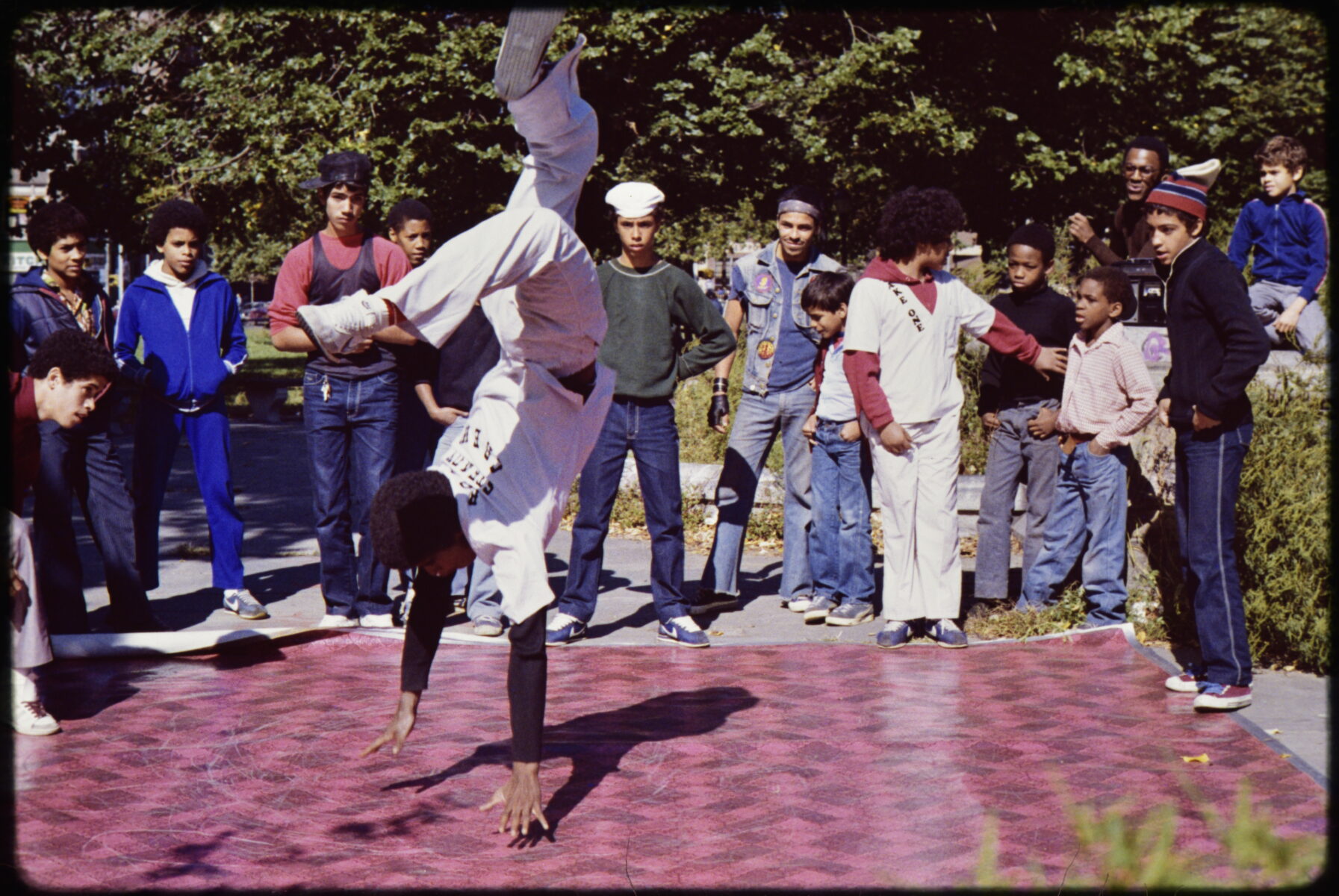

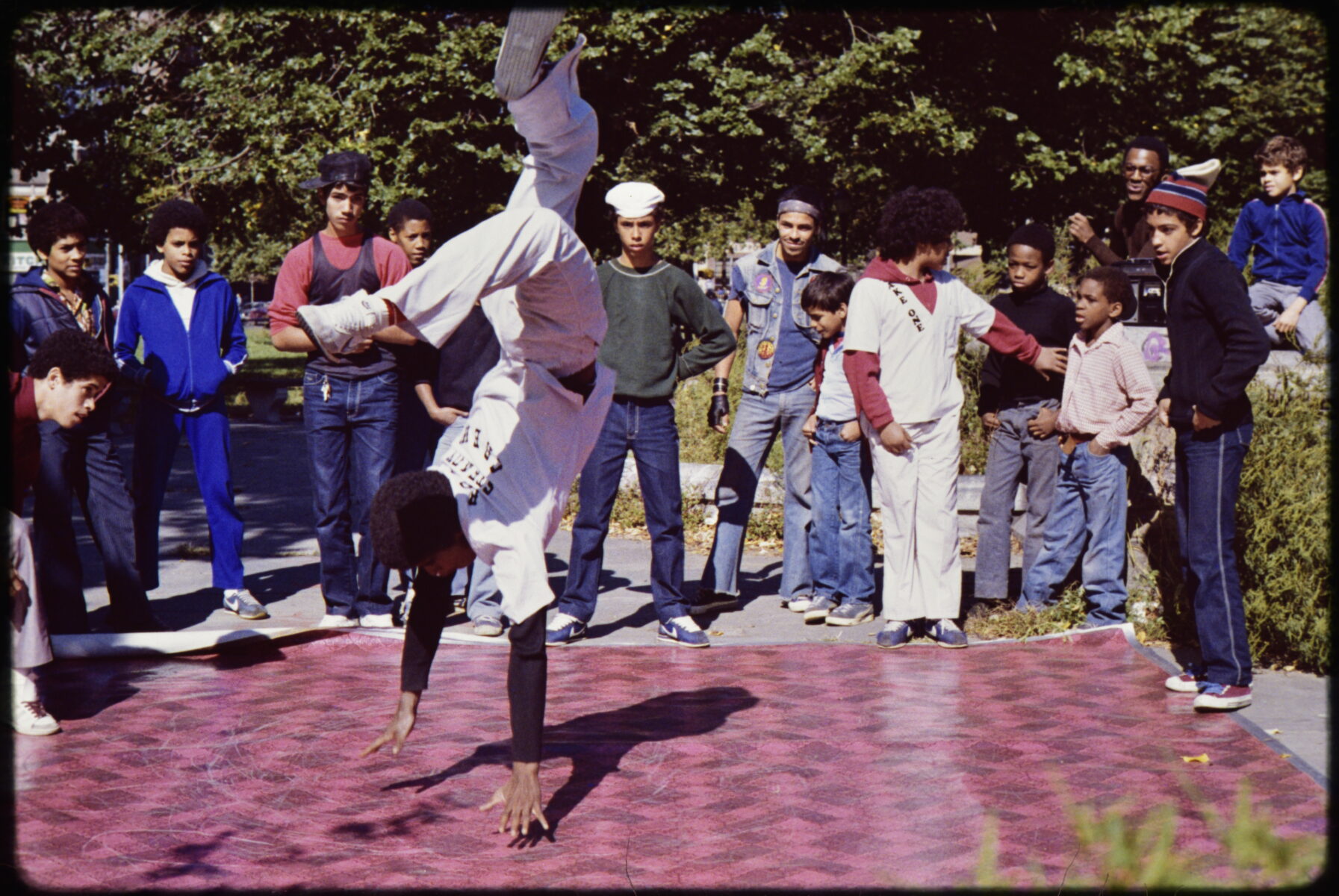

Before eventual world domination, hip-hop began with the DJ Kool Herc block parties of the 70s. It thrived as a South Bronx scene that brought together uber-talented graffiti artists and breakdancing b-boys. MCs with two turntables and a microphone to their name. To this day, it remains the truest portrait of a time long past, and continues to be regarded as one of the most important and imitated music films ever made.

Returning via an exclusive 4K restoration glow-up courtesy of Arrow Films, Wild Style recently celebrated its legacy at the 2025 BFI London Film Festival with two screenings, its maker Charlie Ahearn in attendance. “I was wearing a Wild Style cap the whole time I was in London, people probably thought I slept with that on,” Ahearn, in a velvety red Harrington jacket and a matching baker boy hat, tells me over Zoom. Hung behind him is a painting from a photograph he took at his first hip-hop jam, with Grand Wizzard Theodore’s hand on the decks, and etched in white, the word “SCRATCH”.

For those unfamiliar with Ahearn’s seminal picture, one may recognise his 1992 home movie Doin’ Time in Times Square. A remarkable bird’s-eye view account of frequent criminal activity, Ahearn captures chaotic scenes from his 43rd street apartment window, intercut with family life and the time between the birth of his first and second child. You can imagine my surprise, then, when the film’s star, Ahearn’s son Joe, steps in as tech support for his father’s interview setup.“I shot film on Super 8, on a 16mm Bolex camera, like all good independent filmmakers. The funny thing about that movie was that it was his birth that led me to buy a video camera.”

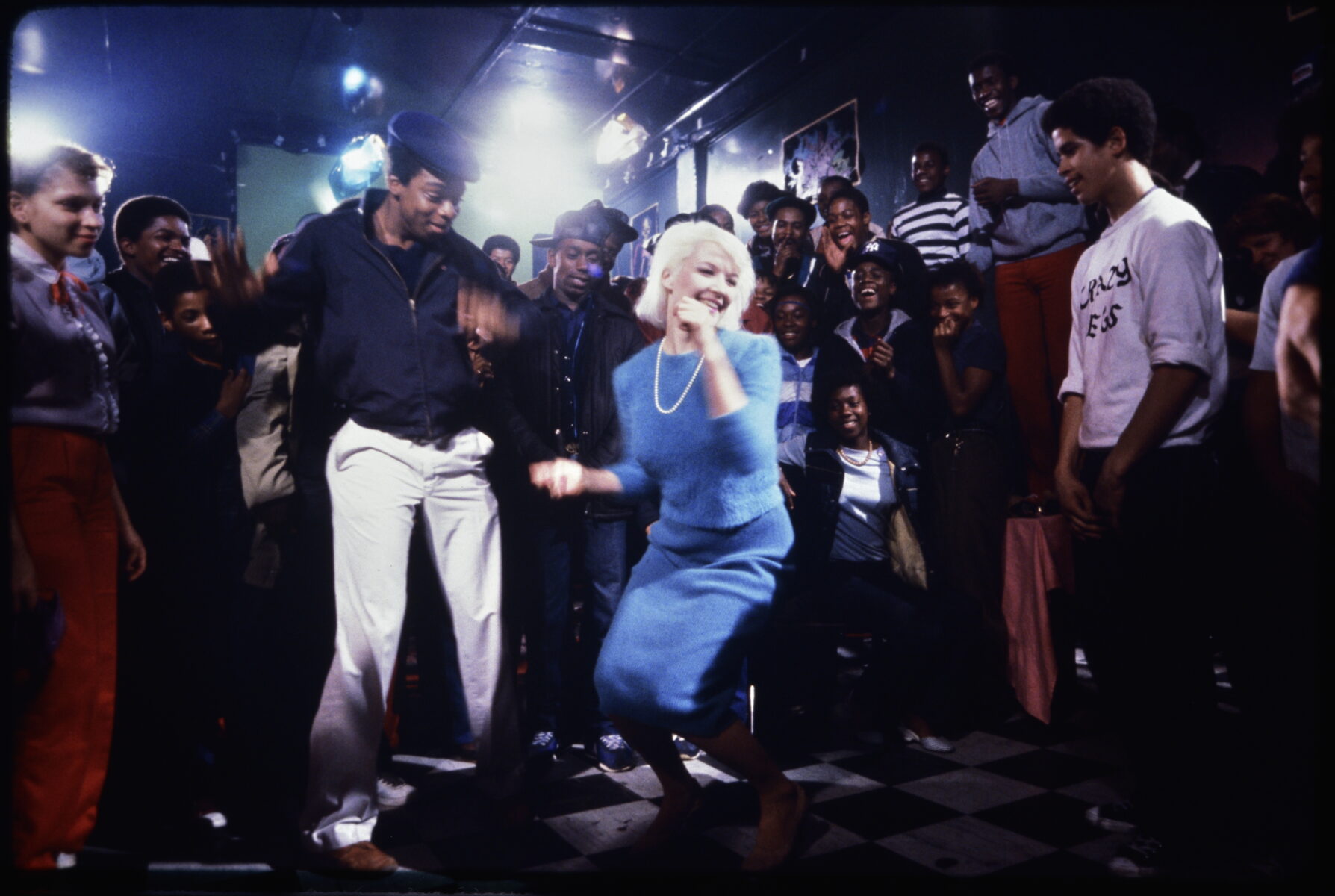

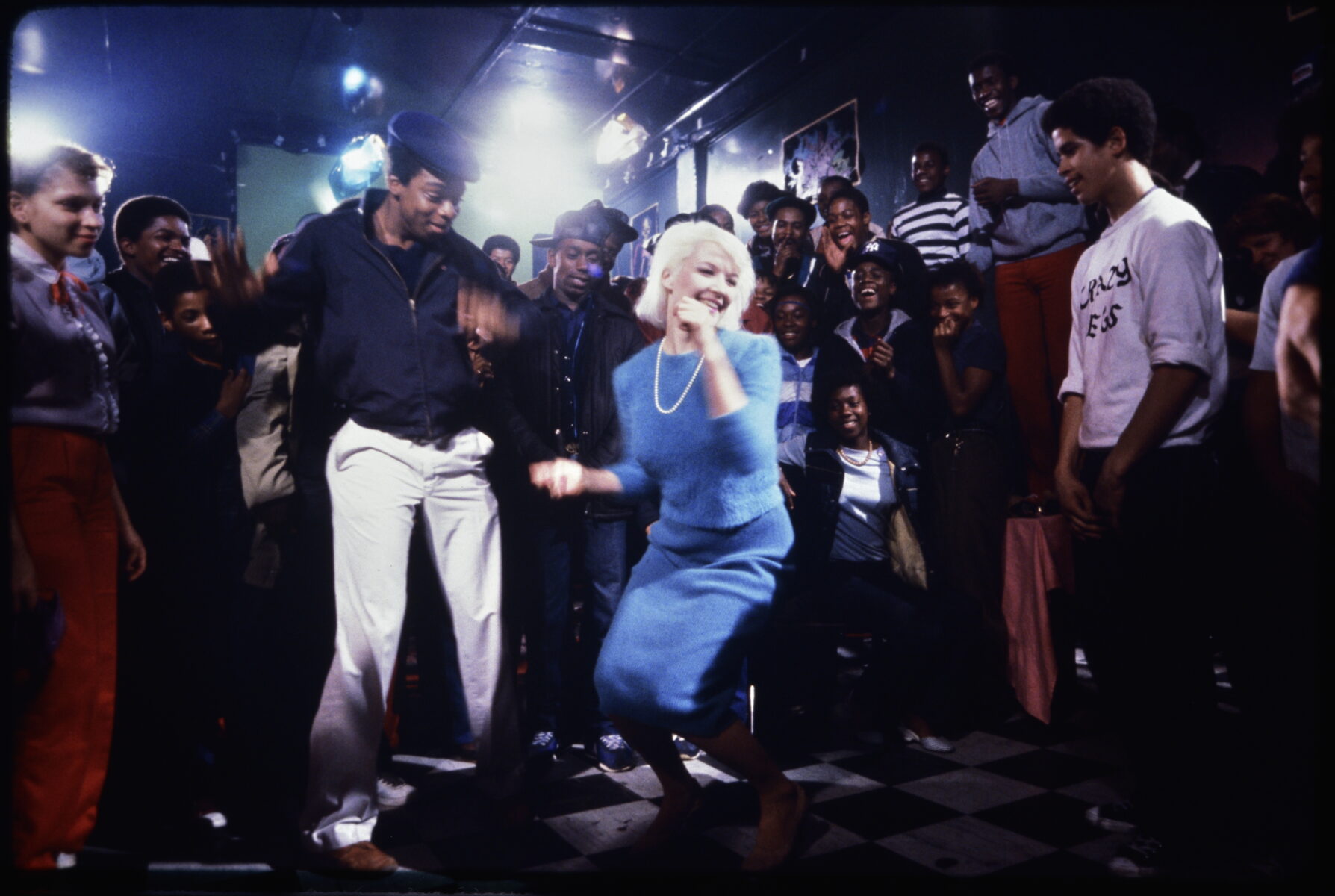

Wild Style is the one that started it all, of course. Ahearn and downtown artist Fred “Fab 5 Freddy” Brathwaite ventured uptown with the aim of documenting an undocumented curiosity. A gloriously gritty, semi-biographical oddity, the story reflects the experiences of its creators. Journalist character Virginia, played by No Wave cinema star Patti Astor, brings uptown hip-hop culture to the attention of the downtown art world.

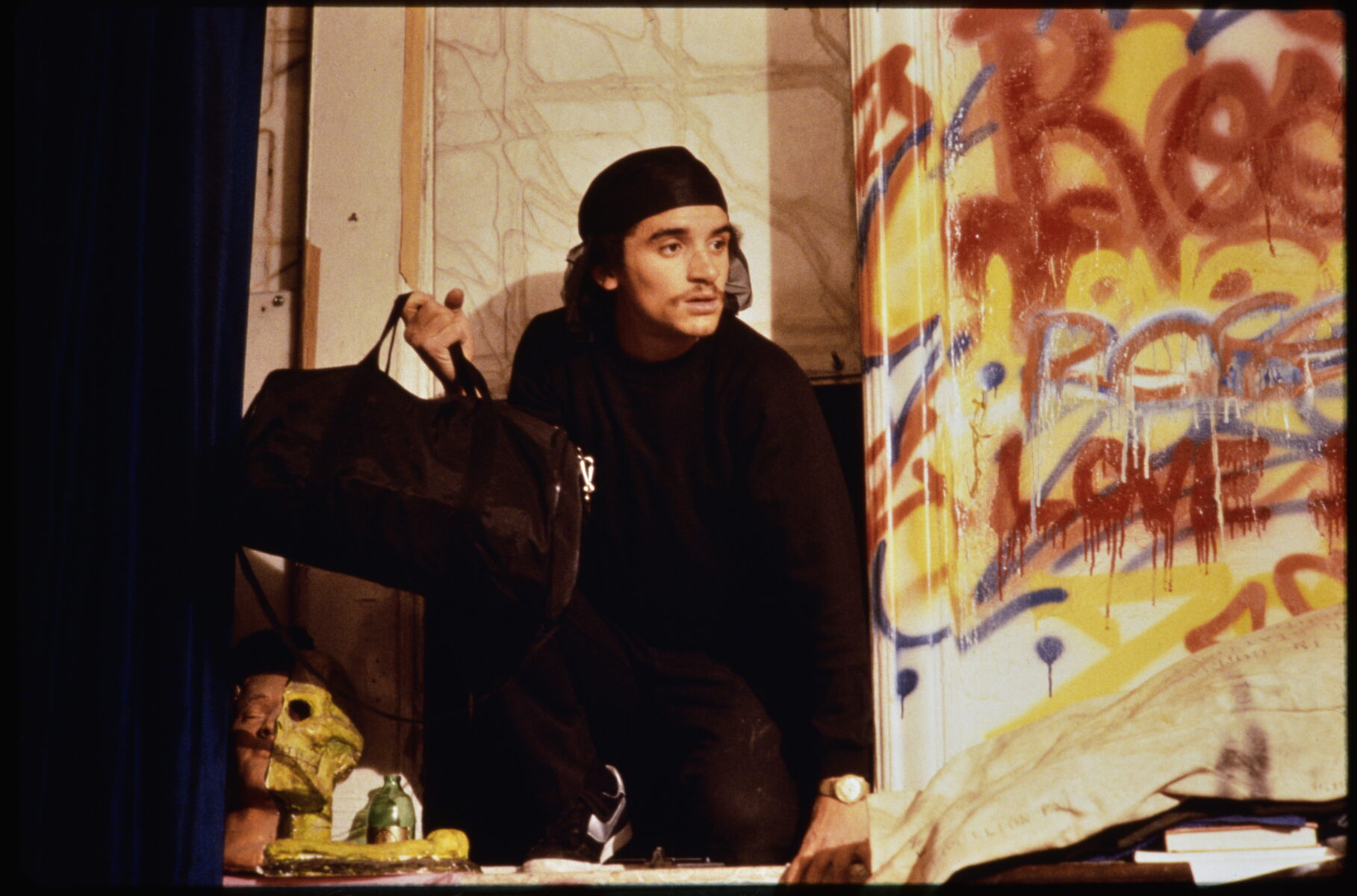

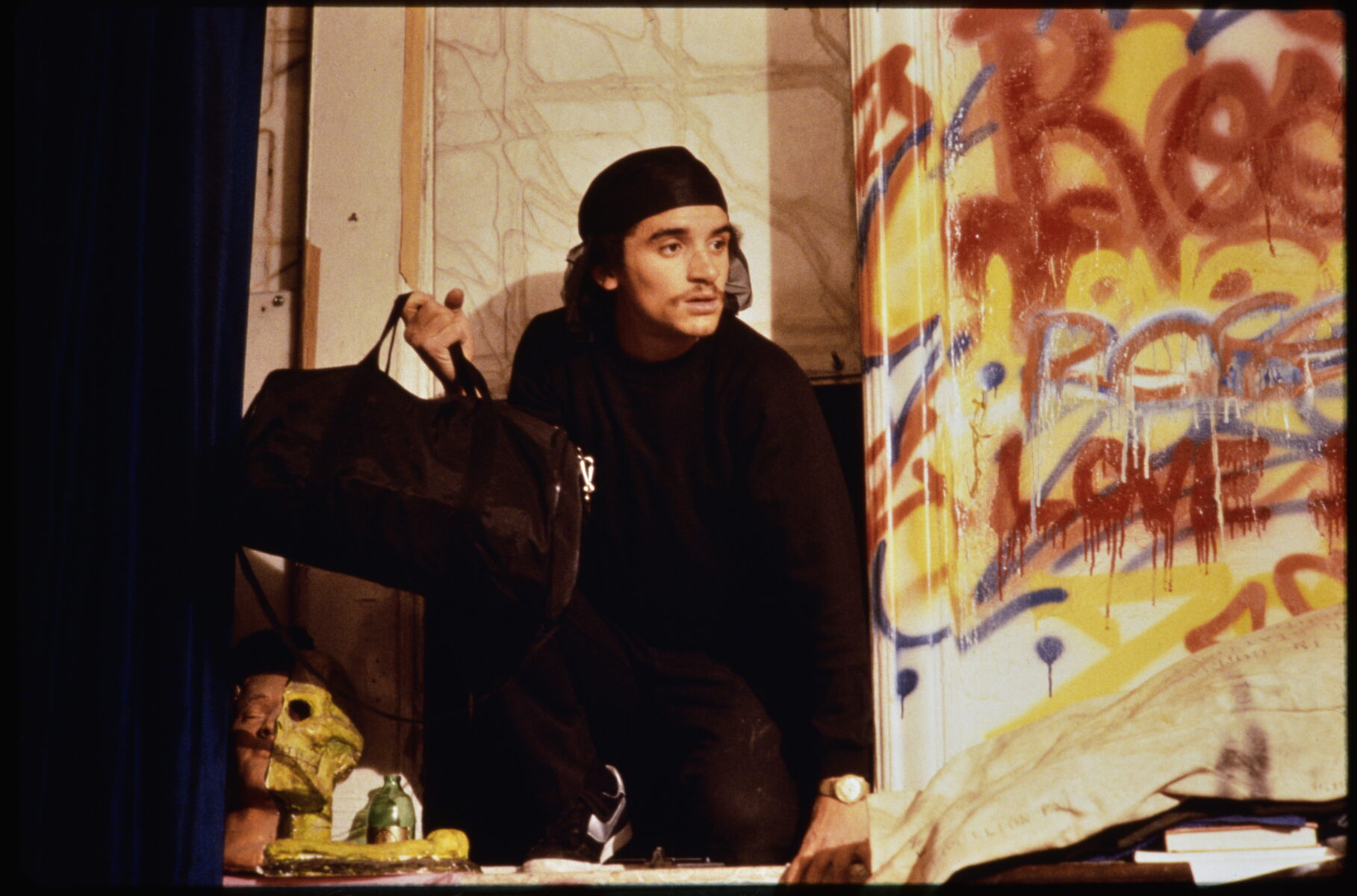

In a case of art imitating life, Lee Quiñones is Raymond, a lone, anonymous graffiti artist under the pseudonym “Zoro”, who scorns the legitimate, commissioned murals of the Union Crew on the walls of playgrounds and business establishments. Sandra “Lady Pink” Fabara plays his love interest. A who’s who of music performances from Grandmaster Flash, Busy Bee, The Fantastic Five, The Cold Crush Brothers and The Rock Steady Crew are sprinkled within the film’s runtime. A band shell decorated by Raymond on the Lower East Side is the source of a culminating rap-break concert.

Entwined with rapper and breaker extended encounters, Wild Style’s soundtrack is just as vibrant and vivacious as the attractive graffiti scrawled across subway trains. Blondie’s Chris Stein collaborated with Brathwaite to produce the breakbeats used in the film, an inspired decision and a source of fixation for future crate diggers. From Mr Bongo comes a special edition reissue package, with bonus Flexi, on colourful blue/orange vinyl.

Hot on the heels of his first solo UK exhibition at Woodbury House, Charlie Ahearn shares anecdotes from his travels in London and his time spent in New York, how Wild Style came to be, and the indelible mark his movie has left on the people touched by its foundational footprint.

How did audiences at the London Film Festival respond to the newly restored version of the film?

We worked for two years on the restoration, and it seems hard to believe. Each theatre at the London Film Festival would hold 400 people; these are large spaces. The fact that it’s blown up in this way, even though it’s so-called a digital copy, it’s way better than what was originally seen in a 35mm projection in a movie theatre back in 1983. What we have is much closer to the original film, and it’s of better quality.

I terribly miss London. They created a second screening at the Prince Charles Cinema, everyone told me that that was the best place to show your film because they have an interest in special pictures. We had a party in the back on the way to the cinema. Lee Quiñones and James White, who’s the person who paid for the 4K restoration, we’re all working together to get this to happen. It was really fun to travel around in a black cab in London, I want to be there right now. We used to have what was called checker cabs in New York, which were school bus yellow. I miss them.

What has surprised you about how new generations interpret or discover the film now?

Well, the film was obviously a success in London. The two theatres were sold out, and a lot of people wanted to talk to me about their experience with the film. How they had seen it when they were 15 years old, and, ‘Now my son is here, and he’s 15.’ I like that, I’ve got grandchildren, and I like to think of things as generational. I told people at the festival that the film feels so tender. As I get older, people get younger.

‘Wild Style’, your art show at Woodbury House, ran for a limited time in tandem with the festival screenings. What did it mean to you to have your work showcased here?

For me, it was an enormous honour and an opportunity to get a chance to show several decades of paintings that I have been making. I also made a lot of new paintings just for this show, which were in some way evocative of the movie. There are a lot of portraits, I would say at least half the paintings are figurative of people like Patti Astor. I love that painting because I feel like she is a spiritual person in the movie, and she’s no longer with us. I’m glad I could paint that for her and keep her alive.

There’s a great Dot-A-Rock painting in the show, he’s on the wall, and behind him are all these flyers, there’s probably 40 at least. This was his flyer collection from hip-hop venues that were showing his group, The Fantastic Five. He was one of the best MCs of that moment in the Bronx. Here he is collecting his flyers, and he invites me over to his house to show me his flyer collection on the wall. I was stunned, and I took a snapshot of the flyers. Later, when I tried to reproduce this photograph, it wasn’t great. It was good enough that other people who collected flyers were amazed at all the variety of venues. It was like having a nice guidebook to hip-hop in 1979, 1980.

As an outsider to the culture of the Bronx in the early 80s, how did you earn the trust of those spaces and communities you wanted to capture?

People ask me, ‘How did you get the trust of people?’ I’m this white guy, I was 27 when I started to make Wild Style. Almost the whole movie is made with people who are teenagers. I think that’s a really radical thing, and it’s teenagers that are deeply involved in street culture, as much as I tried to embrace it and be involved in it. Basically, I was a guest in other people’s homes, but I was a good guest, and that’s how I made the movie. I was always invited into people’s spaces because I had curiosity and totally treated people with respect.

In those days, I didn’t use the term hip-hop very much, and nobody else did, but you would go to a jam and there were always people outside handing out flyers. I got a great flyer collection, but I kept them because they were maps of where it’s happening. There’s no one else here who’s going to be able to tell you everything. So the idea was, in a sense, by handing me a flyer, they’re inviting me to their party. I wasn’t busting into people’s private affairs with a camera; I was just attending to what they were doing, and I did it for a while.

What responsibility do filmmakers like yourself have when portraying a community?

Well, you could say that it’s almost a religious responsibility. I like the word you used. I wouldn’t normally think of it as a responsibility, because it’s such a joy that it’s hardly an irksome task. It’s instead something that’s the most fun, and for me, it’s never stopped. The relationship to at least the people who were in my film has continued on a regular basis. I went out to Cincinnati, and I showed Wild Style with Grand Wizzard Theodore, who invented scratch music when he was only 12 years old. He became the record boy for Grandmaster Flash.

I would like to think that the way in which people were invited to perform in the movie was in keeping with what they wanted from me. Their interest in me was to help them seek more audience or to get more attention and to practice in front of a camera. Certainly, some people like Fred Brathwaite, you could say, really shocked the world with how he was in front of a camera and what kind of skills he showed. But I would say, throughout, everyone got a chance to try out things.

How did early hip-hop jams inform your approach to shooting and designing the film?

The opening shot of the movie is September of ‘81. That’s hardly any time at all, but to me, it seemed like ages. During that time, I was taking pictures of everybody on slide film. No one who was normally taking pictures of their family would do that. But I was an artist, and people who are artists always shot slides because that was a way to make a record of your artwork, and then you put the slides into these plastic things and drop them off at the gallery.

I took my slide projector to the Ecstasy Garage [Disco], there were kids in there with 40oz beers listening to Grand Wizzard Theodore mix. I would be taking photographs of people, and then I would come back the next week and show them on slides on the wall, which would shock everybody. Let’s say, Busy Bee is performing on the microphone, he would talk about whoever was on the slide in the back, and it would seem like we had a show going, which we did. I would scratch on the slides, Busy Bee’s name. That allowed me to have an entranceway to the culture, and the performers, of course, like to have their picture big on the wall. It made them seem like they were stars.

What made graffiti art such an essential foundation for the story and the characters?

If you want to make a picture of early hip-hop, everyone started because they were taggers. They were writing on walls, they were writing their name in books. They were writing something cool. Herc used to write, and he knew that the best writers were on the subways. The subways were actually happening before the music, and all of it happened together. That’s why we like to say that it’s an interrelated part of a culture. This artist, named Phase 2, who is considered by me, one of the best original subway writers, was best friends with Kool Herc.

One of the film’s most famous moments is the throwdown that takes place on a basketball court, The Cold Crush Brothers versus The Fantastic Five. How did it come to be?

It’s my favourite scene in the movie. I was making a film very inexpensively, but also very quickly; spontaneity was really the sense of how things happened. Grandmaster Caz invited me to come to that park to talk about how he worked, and he would explain to me that he and the other fellas would practice their rhymes and write lyrics as they were shooting baskets. They would play basketball; there was a way to relax into so-called work. They wouldn’t sit around a desk and write; the way lyrics are written in early hip-hop was people just did them over and over again.

His apartment, where he lived with his folks, was right behind the basketball court. He wanted to show me his closet; there were, like, eight boxes of sneakers, all different colours. Hats that would match the sneakers exactly in colour. Grandmaster Caz was a fiend for looking good all the time. He then went into his closet, and he pulled out a stack of composition books, which were familiar with junior high school. He spread each of them out over the bed to show me, and they were all filled with rhymes, done in the most exact penmanship, with no cross-outs. I said, ‘How did you write like this?’ If I were writing, I would write down an idea, and I would cross it out to get it better, and I would keep changing it. He said, ‘Once I write it in the book, it’s complete, and I don’t change it. ’ But that’s the process. Isn’t that a cool story?

How has your relationship to Wild Style changed over the decades since its release?

I’m looking at the film, and I’m thinking, Lee and Pink were very, very young. Especially Pink, she was 16 when I met her. It’s puppy love, their relationship. I was sitting in the audience with Lee, which was such a gas because we’re really funny together. He’s saying, ‘I feel like I’m falling in love with her all over again’. He was talking about how he fell in love with her hair, she snaps at people, she has a really mean tongue, and she just looks beautiful in the movie. I think she’s a really dynamite actress. Of course, there are no actors in the movie; they are, in a sense, playing who they were in real life, not playing someone else. But still, just because you’re playing yourself doesn’t mean you’re going to be good. Actually, most people completely freeze up when a camera points towards them.

It’s a history of hip-hop. It was a culture built in neighbourhoods where everyone would call each other ‘cuz’ as a term of endearment. By the time [Wild Style] happened, it had already been gestating for 10 years.

Have you ever considered making a film about contemporary hip-hop?

Actually, I haven’t. Not because I’m not interested in it, but what I was looking at and experienced disappeared in a year. All those clubs that were there disappeared. The club culture was really being fed by local interest; the junior high school students knew each other and would see each other at these jams, and it sort of existed. You had Run DMC and groups that were successful, and it became like ‘what’s a DJ?’ The DJ was the centre point of the culture before that. The subway graffiti also completely disappeared by 1983. So the subway graffiti is gone, and the parties that I knew were gone.

The film was a success, which was good for me. I don’t know how much it helped everybody else. It did help some people, but probably not to the extent that the film became famous for itself. What am I going to make a film about now? I mean, you could make a film about lots of things, and certainly music is a good one. Maybe there’s some young troubadour who’s writing great rhymes, and they would make a nice portrait film.

Wild Style is available to stream exclusively now on the Arrow Video Channel and to own on 4K UHD & Blu-ray

Words – Douglas Jardim

Photography – Cathy Campbell & Martha Cooper

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

A slice-of-life look at early ’80s NYC, cult classic Wild Style is the endlessly sampled snapshot of an exciting underground movement in its infancy. Over 30 years later, independent filmmaker Charlie Ahearn breaks down the original hip-hop feature in a Wonderland exclusive.

Before eventual world domination, hip-hop began with the DJ Kool Herc block parties of the 70s. It thrived as a South Bronx scene that brought together uber-talented graffiti artists and breakdancing b-boys. MCs with two turntables and a microphone to their name. To this day, it remains the truest portrait of a time long past, and continues to be regarded as one of the most important and imitated music films ever made.

Returning via an exclusive 4K restoration glow-up courtesy of Arrow Films, Wild Style recently celebrated its legacy at the 2025 BFI London Film Festival with two screenings, its maker Charlie Ahearn in attendance. “I was wearing a Wild Style cap the whole time I was in London, people probably thought I slept with that on,” Ahearn, in a velvety red Harrington jacket and a matching baker boy hat, tells me over Zoom. Hung behind him is a painting from a photograph he took at his first hip-hop jam, with Grand Wizzard Theodore’s hand on the decks, and etched in white, the word “SCRATCH”.

For those unfamiliar with Ahearn’s seminal picture, one may recognise his 1992 home movie Doin’ Time in Times Square. A remarkable bird’s-eye view account of frequent criminal activity, Ahearn captures chaotic scenes from his 43rd street apartment window, intercut with family life and the time between the birth of his first and second child. You can imagine my surprise, then, when the film’s star, Ahearn’s son Joe, steps in as tech support for his father’s interview setup.“I shot film on Super 8, on a 16mm Bolex camera, like all good independent filmmakers. The funny thing about that movie was that it was his birth that led me to buy a video camera.”

Wild Style is the one that started it all, of course. Ahearn and downtown artist Fred “Fab 5 Freddy” Brathwaite ventured uptown with the aim of documenting an undocumented curiosity. A gloriously gritty, semi-biographical oddity, the story reflects the experiences of its creators. Journalist character Virginia, played by No Wave cinema star Patti Astor, brings uptown hip-hop culture to the attention of the downtown art world.

In a case of art imitating life, Lee Quiñones is Raymond, a lone, anonymous graffiti artist under the pseudonym “Zoro”, who scorns the legitimate, commissioned murals of the Union Crew on the walls of playgrounds and business establishments. Sandra “Lady Pink” Fabara plays his love interest. A who’s who of music performances from Grandmaster Flash, Busy Bee, The Fantastic Five, The Cold Crush Brothers and The Rock Steady Crew are sprinkled within the film’s runtime. A band shell decorated by Raymond on the Lower East Side is the source of a culminating rap-break concert.

Entwined with rapper and breaker extended encounters, Wild Style’s soundtrack is just as vibrant and vivacious as the attractive graffiti scrawled across subway trains. Blondie’s Chris Stein collaborated with Brathwaite to produce the breakbeats used in the film, an inspired decision and a source of fixation for future crate diggers. From Mr Bongo comes a special edition reissue package, with bonus Flexi, on colourful blue/orange vinyl.

Hot on the heels of his first solo UK exhibition at Woodbury House, Charlie Ahearn shares anecdotes from his travels in London and his time spent in New York, how Wild Style came to be, and the indelible mark his movie has left on the people touched by its foundational footprint.

How did audiences at the London Film Festival respond to the newly restored version of the film?

We worked for two years on the restoration, and it seems hard to believe. Each theatre at the London Film Festival would hold 400 people; these are large spaces. The fact that it’s blown up in this way, even though it’s so-called a digital copy, it’s way better than what was originally seen in a 35mm projection in a movie theatre back in 1983. What we have is much closer to the original film, and it’s of better quality.

I terribly miss London. They created a second screening at the Prince Charles Cinema, everyone told me that that was the best place to show your film because they have an interest in special pictures. We had a party in the back on the way to the cinema. Lee Quiñones and James White, who’s the person who paid for the 4K restoration, we’re all working together to get this to happen. It was really fun to travel around in a black cab in London, I want to be there right now. We used to have what was called checker cabs in New York, which were school bus yellow. I miss them.

What has surprised you about how new generations interpret or discover the film now?

Well, the film was obviously a success in London. The two theatres were sold out, and a lot of people wanted to talk to me about their experience with the film. How they had seen it when they were 15 years old, and, ‘Now my son is here, and he’s 15.’ I like that, I’ve got grandchildren, and I like to think of things as generational. I told people at the festival that the film feels so tender. As I get older, people get younger.

‘Wild Style’, your art show at Woodbury House, ran for a limited time in tandem with the festival screenings. What did it mean to you to have your work showcased here?

For me, it was an enormous honour and an opportunity to get a chance to show several decades of paintings that I have been making. I also made a lot of new paintings just for this show, which were in some way evocative of the movie. There are a lot of portraits, I would say at least half the paintings are figurative of people like Patti Astor. I love that painting because I feel like she is a spiritual person in the movie, and she’s no longer with us. I’m glad I could paint that for her and keep her alive.

There’s a great Dot-A-Rock painting in the show, he’s on the wall, and behind him are all these flyers, there’s probably 40 at least. This was his flyer collection from hip-hop venues that were showing his group, The Fantastic Five. He was one of the best MCs of that moment in the Bronx. Here he is collecting his flyers, and he invites me over to his house to show me his flyer collection on the wall. I was stunned, and I took a snapshot of the flyers. Later, when I tried to reproduce this photograph, it wasn’t great. It was good enough that other people who collected flyers were amazed at all the variety of venues. It was like having a nice guidebook to hip-hop in 1979, 1980.

As an outsider to the culture of the Bronx in the early 80s, how did you earn the trust of those spaces and communities you wanted to capture?

People ask me, ‘How did you get the trust of people?’ I’m this white guy, I was 27 when I started to make Wild Style. Almost the whole movie is made with people who are teenagers. I think that’s a really radical thing, and it’s teenagers that are deeply involved in street culture, as much as I tried to embrace it and be involved in it. Basically, I was a guest in other people’s homes, but I was a good guest, and that’s how I made the movie. I was always invited into people’s spaces because I had curiosity and totally treated people with respect.

In those days, I didn’t use the term hip-hop very much, and nobody else did, but you would go to a jam and there were always people outside handing out flyers. I got a great flyer collection, but I kept them because they were maps of where it’s happening. There’s no one else here who’s going to be able to tell you everything. So the idea was, in a sense, by handing me a flyer, they’re inviting me to their party. I wasn’t busting into people’s private affairs with a camera; I was just attending to what they were doing, and I did it for a while.

What responsibility do filmmakers like yourself have when portraying a community?

Well, you could say that it’s almost a religious responsibility. I like the word you used. I wouldn’t normally think of it as a responsibility, because it’s such a joy that it’s hardly an irksome task. It’s instead something that’s the most fun, and for me, it’s never stopped. The relationship to at least the people who were in my film has continued on a regular basis. I went out to Cincinnati, and I showed Wild Style with Grand Wizzard Theodore, who invented scratch music when he was only 12 years old. He became the record boy for Grandmaster Flash.

I would like to think that the way in which people were invited to perform in the movie was in keeping with what they wanted from me. Their interest in me was to help them seek more audience or to get more attention and to practice in front of a camera. Certainly, some people like Fred Brathwaite, you could say, really shocked the world with how he was in front of a camera and what kind of skills he showed. But I would say, throughout, everyone got a chance to try out things.

How did early hip-hop jams inform your approach to shooting and designing the film?

The opening shot of the movie is September of ‘81. That’s hardly any time at all, but to me, it seemed like ages. During that time, I was taking pictures of everybody on slide film. No one who was normally taking pictures of their family would do that. But I was an artist, and people who are artists always shot slides because that was a way to make a record of your artwork, and then you put the slides into these plastic things and drop them off at the gallery.

I took my slide projector to the Ecstasy Garage [Disco], there were kids in there with 40oz beers listening to Grand Wizzard Theodore mix. I would be taking photographs of people, and then I would come back the next week and show them on slides on the wall, which would shock everybody. Let’s say, Busy Bee is performing on the microphone, he would talk about whoever was on the slide in the back, and it would seem like we had a show going, which we did. I would scratch on the slides, Busy Bee’s name. That allowed me to have an entranceway to the culture, and the performers, of course, like to have their picture big on the wall. It made them seem like they were stars.

What made graffiti art such an essential foundation for the story and the characters?

If you want to make a picture of early hip-hop, everyone started because they were taggers. They were writing on walls, they were writing their name in books. They were writing something cool. Herc used to write, and he knew that the best writers were on the subways. The subways were actually happening before the music, and all of it happened together. That’s why we like to say that it’s an interrelated part of a culture. This artist, named Phase 2, who is considered by me, one of the best original subway writers, was best friends with Kool Herc.

One of the film’s most famous moments is the throwdown that takes place on a basketball court, The Cold Crush Brothers versus The Fantastic Five. How did it come to be?

It’s my favourite scene in the movie. I was making a film very inexpensively, but also very quickly; spontaneity was really the sense of how things happened. Grandmaster Caz invited me to come to that park to talk about how he worked, and he would explain to me that he and the other fellas would practice their rhymes and write lyrics as they were shooting baskets. They would play basketball; there was a way to relax into so-called work. They wouldn’t sit around a desk and write; the way lyrics are written in early hip-hop was people just did them over and over again.

His apartment, where he lived with his folks, was right behind the basketball court. He wanted to show me his closet; there were, like, eight boxes of sneakers, all different colours. Hats that would match the sneakers exactly in colour. Grandmaster Caz was a fiend for looking good all the time. He then went into his closet, and he pulled out a stack of composition books, which were familiar with junior high school. He spread each of them out over the bed to show me, and they were all filled with rhymes, done in the most exact penmanship, with no cross-outs. I said, ‘How did you write like this?’ If I were writing, I would write down an idea, and I would cross it out to get it better, and I would keep changing it. He said, ‘Once I write it in the book, it’s complete, and I don’t change it. ’ But that’s the process. Isn’t that a cool story?

How has your relationship to Wild Style changed over the decades since its release?

I’m looking at the film, and I’m thinking, Lee and Pink were very, very young. Especially Pink, she was 16 when I met her. It’s puppy love, their relationship. I was sitting in the audience with Lee, which was such a gas because we’re really funny together. He’s saying, ‘I feel like I’m falling in love with her all over again’. He was talking about how he fell in love with her hair, she snaps at people, she has a really mean tongue, and she just looks beautiful in the movie. I think she’s a really dynamite actress. Of course, there are no actors in the movie; they are, in a sense, playing who they were in real life, not playing someone else. But still, just because you’re playing yourself doesn’t mean you’re going to be good. Actually, most people completely freeze up when a camera points towards them.

It’s a history of hip-hop. It was a culture built in neighbourhoods where everyone would call each other ‘cuz’ as a term of endearment. By the time [Wild Style] happened, it had already been gestating for 10 years.

Have you ever considered making a film about contemporary hip-hop?

Actually, I haven’t. Not because I’m not interested in it, but what I was looking at and experienced disappeared in a year. All those clubs that were there disappeared. The club culture was really being fed by local interest; the junior high school students knew each other and would see each other at these jams, and it sort of existed. You had Run DMC and groups that were successful, and it became like ‘what’s a DJ?’ The DJ was the centre point of the culture before that. The subway graffiti also completely disappeared by 1983. So the subway graffiti is gone, and the parties that I knew were gone.

The film was a success, which was good for me. I don’t know how much it helped everybody else. It did help some people, but probably not to the extent that the film became famous for itself. What am I going to make a film about now? I mean, you could make a film about lots of things, and certainly music is a good one. Maybe there’s some young troubadour who’s writing great rhymes, and they would make a nice portrait film.

Wild Style is available to stream exclusively now on the Arrow Video Channel and to own on 4K UHD & Blu-ray

Words – Douglas Jardim

Photography – Cathy Campbell & Martha Cooper

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.