Rewrite

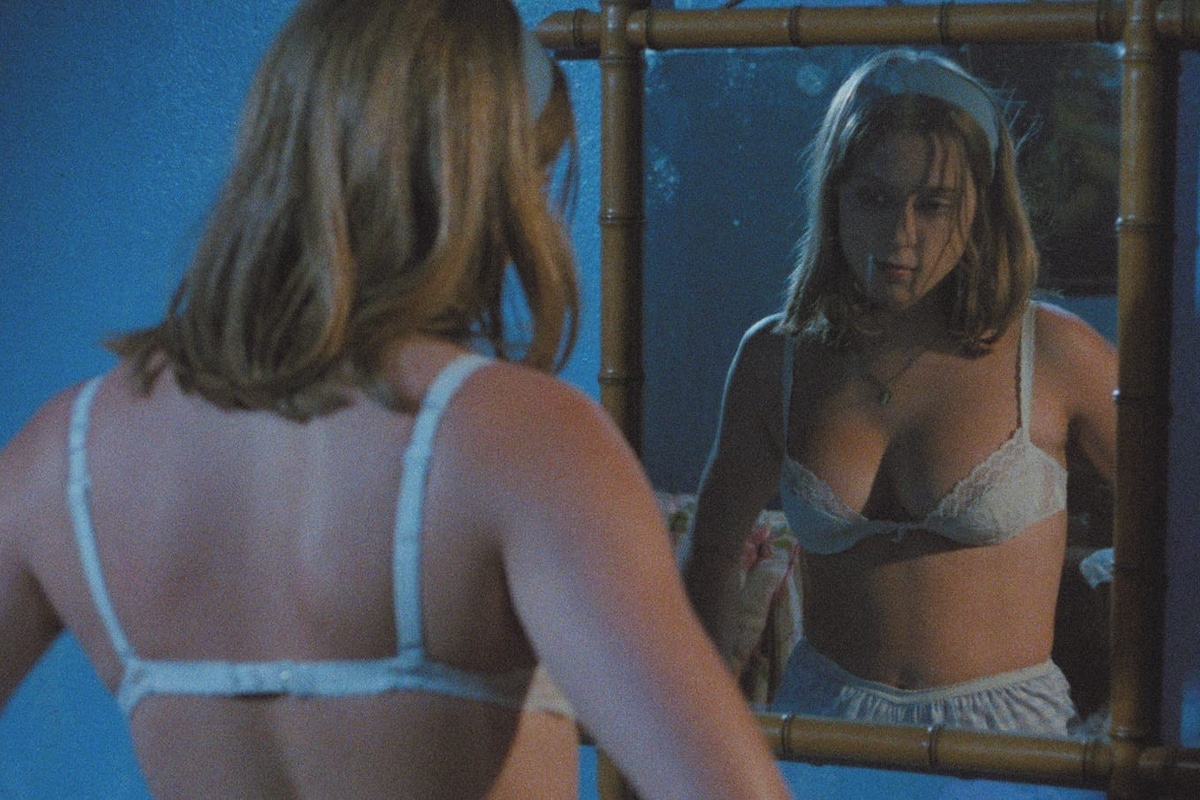

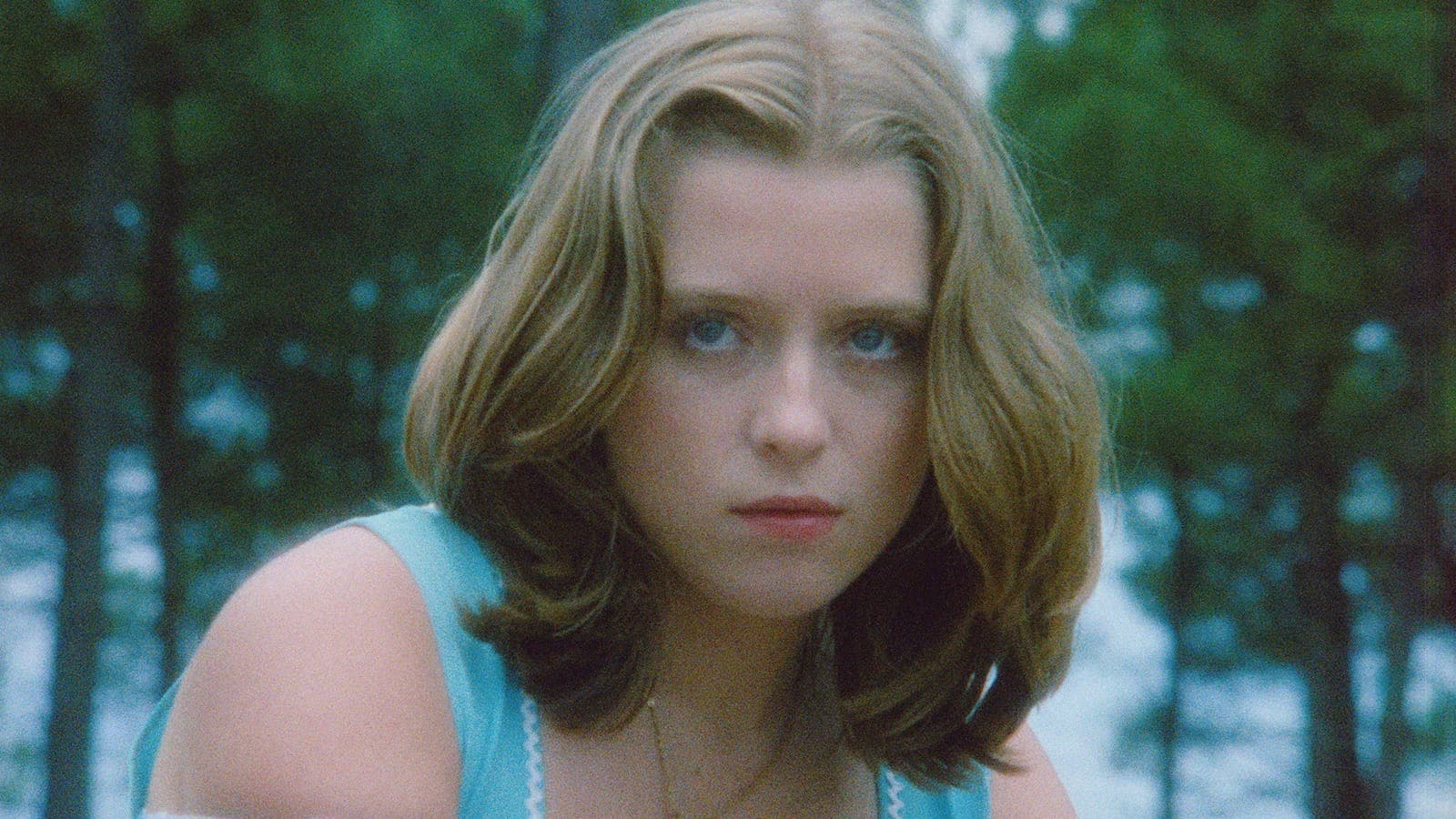

Lead ImageA Real Young Girl, 1976(Film still)

The fifth season of Girlhood Studies is called Primary Sources. How have notions of adaptation, translation, and the thin line between fiction and memory formed depictions of girlhood? Expect the same studies of film and visual culture, but with a closer look at the texts they draw from.

Catherine Breillat has a great anecdote about Roberto Rossellini from the evening before she began filming A Real Young Girl (1976). Over dinner, the director-elder asked her a question. “What do you think you’re going to add to the portrayal of young girls that hasn’t already been done by men?” Even at 22, Breillat answered with the signature precision that would define her filmmaking. “The gaze of shame. You’re the ones who gave us our shame, and we’re the ones who carry it.”

A new book by Breillat released this month via Semiotext(e) – in-conversation with Murielle Joudet, translated by Christine Pichini – consists of a long-form discussion with the director of that debut feature, as well as 36 Fillette (1988), Romance (1999), Fat Girl (2001), Last Summer (2023), and many others. In dialogue with Joudet over a series of meet-ups, the filmmaker discusses her career, her inspirations, her traumas and her recoveries of various kinds. Reading it, I found myself underlining nearly the entire book: “Adolescence is a muddle, and you sort it out afterward”; “Unpacking ugliness, I find that very, very beautiful”; “Everything has to be sublime in a movie dress, especially a red one.” Like the harsh conclusions she draws in most of her films, even the book’s title hits you with a short, sharp, shock: I Only Believe in Myself.

At a glance, Breillat is an unusual topic for a column dedicated to girlhood: not because her films haven’t featured many teenage girls, but because the sex, death and visceral abjection they depict are so strictly 18 plus. In a lifelong examination of the primal, sex is the currency Breillat’s women trade in; the line between pleasure and pain the rate of exchange. Still, I assumed I had written about her in this column before, but I can’t see that I have. Turns out Breillat is hard to write about, just as she is hard to watch.

From the outset, Breillat’s interviewer Joudet declares her stance: the young-girlness of Breillat is core to understanding her work. As she writes in the book’s introduction, brilliantly titled An Old Young Girl (it could be an alternative name for my own project), even when the director films adult actresses in adult scenarios, “she captures absolute adolescence.” Joudet writes of her own long summer holidays in Lebanon as a teenager: all swimming pools, “thundering boredom”, and waiting for adult life, sexual and free, to begin. Soon enough, she finds all those “silent, incommunicable experiences” expressed, or illuminated, in Breillat.

I don’t suggest that the sexually explicit content of these films is suited to the very young. But Breillat’s book prompted me to think about what the director’s expressions of girlhood really evidence; that is, the fact that coming-of-age in a masculine and misogynist world, women have a different relationship to the notion of shame and exposure onscreen in the first place. We can sit in that bright light, because that feeling of being under a gaze has always been there. It’s no wonder Breillat’s films are always uncomfortably lit, almost too sharp (I think of the stark white interiors and dress of Romance, or the colour-blocked clothes in Fat Girl, lifted from a sitcom). And it’s no wonder male critics have struggled to understand what Breillat is getting at.

Banned and unseen in most countries for some decades, A Real Young Girl (based on Breillat’s novel Le Soupirail) is an uninhibited portrait of burgeoning sexuality over the course of a bored summer at home. The year is 1963, and the setting is a dreary seaside town (a continuing obsession of Breillat’s). That the character is called Alice lends itself well to the character’s headband and girlish garments, but also to the surrealistic landscape the director sends her questing through: sandy beaches with dog carcasses, woodland thickets in soft focus. Critics latched onto the extreme depictions of masturbation – one, famously, involving worms – but for me, it’s the more domestic moments that stick in the mind, like Alice serving her parents food in their dirty kitchen wearing a bikini. In one early scene, Alice, alone in her bedroom, examines and touches her body in the mirror, changing into a hyper-babyish pyjama set. She then immediately vomits all over it once in bed. It’s like a corporeal rejection of what an audience expects when a young girl undresses in front of the camera (and has its comparable moment in Fat Girl, in the scene in which Anaïs lifts up her nightie in front of the mirror). The gaze, in A Real Young Girl, is always Alice’s herself. “Alice doesn’t do languid poses for the [male] photographer’s eye,” Breillat confirms. “She makes a devastating inventory of that body that’s blossoming and oozing from everywhere from her own, unforgiving eye.”

I Only Believe in Myself is especially revealing on the origins of 36 Fillette, Breillat’s third film. Known in English as Virgin or Junior Size 36, and based on her 1987 novel, it is the film that most closely maps onto the director’s own memories of girlhood: specifically, her survival of an attempted rape at the age of 14. In 36 Fillette, Lili (Delphine Zentout), who is holidaying with her family on the French coast, hitchhikes to a local disco where she meets a much older playboy. Breillat tells the anecdote the story is based on in the book’s first pages: a time when she thought “nightclubs were the most important thing in the world”, and she hitchhiked to one with her sister every night of the summer vacation. Like Lili, she met a man there (“very seductive, but already decaying”) and was convinced to go up to his hotel room one night. As adapted in 36 Fillette, the experience consists of a painfully drawn-out negotiation in which the man continues to pressure Lili into sex, and ends with her injuring him and escaping. (It’s during this sequence that we also see an early iteration of the girl’s fingers spread over her eyes that would become one of the most memorable stills of Fat Girl).

For Breillat, filming something deemed unfilmable is the essence of cinema – and is what makes it “not obscene.” But reading interviews with the director, it’s clear that most of what we find shocking in her work comes from inside the house. Breillat’s powerful memories of her actual girlhood give them their substance. That includes the violence of her real encounter as a 14-year-old, for instance, but also banal textures of girlhood’s dailiness: family fights, sitting in cafes, waiting around, waiting for the bus. Sometimes you could blink and be in an Éric Rohmer film (incidentally, Breillat sometimes drew on Rohmerienne dialogue to rehearse her actors). But in Rohmer’s modest films, the teenagers are contained; Breillat’s are caged creatures barking to be freed. But even among all their distressing events, Breillat’s endless summer vacations pay tribute to the space boredom offers – the way female adolescence “lets you dream, (and) create your own world that protects you from any conditioning”, as she states in I Only Believe in Myself.

Alice, Anaïs, Lili: even in their wildness, they have the self-possession of the not-yet-conditioned. It’s the other side of the coin of girlhood’s naivety: it brings the girls into extreme scenarios with men, but there is also a certain resilience in the “not-knowing-yet.” It’s the undomesticated energy of these teen-girl protagonists that is so enthralling; it’s what, as Breillat reveals, pulls her back to that time like an eternal return. “It’s my favourite cinematic subject!” she giggles about her tendency to only ever refer to “young girls”, rarely women. “I don’t know what a woman is!”

In the classic ‘rape revenge’ drama, a young woman seeks vengeance against her attacker, taking justice into her own hands. But the violence of Breillat’s movies, when it does occur, is never typically structured. These movies are, after all, very funny. And the men, at least in A Real Young Girl and 36 Fillette, are there to be laughed at. To be observed by us, in all their nudity and ridiculousness, and found wanting. Yes, the men pose a threat. But at the same time, in her filmmaking, Breillat twists them and makes their very masculinity seem small. She takes the glare of the shame she felt in her own girlhood – the one she mentioned to Rossellini – and throws it over men like a fluorescent overhead light.

Just think of the long, drawn-out seduction scene of 36 Fillette, inspired by the actual playboy who targeted Breillat as a girl. In it, Lili tells him off, and makes him absurd. “You wanna cut me in half, huh!”, she cries, calling him a pig as she throws on her jacket to leave. (According to the interview, Breillat said that in real life, too). We can see Breillat’s filmmaking in the same way: as a kind of “getting the final word”. The most memorable image of 36 Fillette, in the end, is the vivid smile Lili breaks into at the end of the film.

“The artistic act isn’t mannered, it’s violent, whether you like it or not.” The carnage of Breillat’s films – the violence, blood and sexual explicitness – renders them not suitable for girls of the age she is depicting. They are made, instead, for women for whom cinema has offered few total mirrors to our experience. As she puts it: “I’m a woman who started making cinema in an era when they talked about ‘women’s films’: delicateness, modesty and feminine refinement. And I wanted … scratch! A man’s thing.” There’s a reason all of us old young girls do not find Breillat’s films as ‘unwatchable’ as old young men. Because even at the extreme edge of what’s allowable, they are all a conversation with the unseen parts of ourselves.

I Only Believe in Myself. Somehow, I needed to hear that.

I Only Believe in Myself: Conversation with Murielle Joudet by Catherine Breillat is published by Semiotext(e) and is out now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageA Real Young Girl, 1976(Film still)

The fifth season of Girlhood Studies is called Primary Sources. How have notions of adaptation, translation, and the thin line between fiction and memory formed depictions of girlhood? Expect the same studies of film and visual culture, but with a closer look at the texts they draw from.

Catherine Breillat has a great anecdote about Roberto Rossellini from the evening before she began filming A Real Young Girl (1976). Over dinner, the director-elder asked her a question. “What do you think you’re going to add to the portrayal of young girls that hasn’t already been done by men?” Even at 22, Breillat answered with the signature precision that would define her filmmaking. “The gaze of shame. You’re the ones who gave us our shame, and we’re the ones who carry it.”

A new book by Breillat released this month via Semiotext(e) – in-conversation with Murielle Joudet, translated by Christine Pichini – consists of a long-form discussion with the director of that debut feature, as well as 36 Fillette (1988), Romance (1999), Fat Girl (2001), Last Summer (2023), and many others. In dialogue with Joudet over a series of meet-ups, the filmmaker discusses her career, her inspirations, her traumas and her recoveries of various kinds. Reading it, I found myself underlining nearly the entire book: “Adolescence is a muddle, and you sort it out afterward”; “Unpacking ugliness, I find that very, very beautiful”; “Everything has to be sublime in a movie dress, especially a red one.” Like the harsh conclusions she draws in most of her films, even the book’s title hits you with a short, sharp, shock: I Only Believe in Myself.

At a glance, Breillat is an unusual topic for a column dedicated to girlhood: not because her films haven’t featured many teenage girls, but because the sex, death and visceral abjection they depict are so strictly 18 plus. In a lifelong examination of the primal, sex is the currency Breillat’s women trade in; the line between pleasure and pain the rate of exchange. Still, I assumed I had written about her in this column before, but I can’t see that I have. Turns out Breillat is hard to write about, just as she is hard to watch.

From the outset, Breillat’s interviewer Joudet declares her stance: the young-girlness of Breillat is core to understanding her work. As she writes in the book’s introduction, brilliantly titled An Old Young Girl (it could be an alternative name for my own project), even when the director films adult actresses in adult scenarios, “she captures absolute adolescence.” Joudet writes of her own long summer holidays in Lebanon as a teenager: all swimming pools, “thundering boredom”, and waiting for adult life, sexual and free, to begin. Soon enough, she finds all those “silent, incommunicable experiences” expressed, or illuminated, in Breillat.

I don’t suggest that the sexually explicit content of these films is suited to the very young. But Breillat’s book prompted me to think about what the director’s expressions of girlhood really evidence; that is, the fact that coming-of-age in a masculine and misogynist world, women have a different relationship to the notion of shame and exposure onscreen in the first place. We can sit in that bright light, because that feeling of being under a gaze has always been there. It’s no wonder Breillat’s films are always uncomfortably lit, almost too sharp (I think of the stark white interiors and dress of Romance, or the colour-blocked clothes in Fat Girl, lifted from a sitcom). And it’s no wonder male critics have struggled to understand what Breillat is getting at.

Banned and unseen in most countries for some decades, A Real Young Girl (based on Breillat’s novel Le Soupirail) is an uninhibited portrait of burgeoning sexuality over the course of a bored summer at home. The year is 1963, and the setting is a dreary seaside town (a continuing obsession of Breillat’s). That the character is called Alice lends itself well to the character’s headband and girlish garments, but also to the surrealistic landscape the director sends her questing through: sandy beaches with dog carcasses, woodland thickets in soft focus. Critics latched onto the extreme depictions of masturbation – one, famously, involving worms – but for me, it’s the more domestic moments that stick in the mind, like Alice serving her parents food in their dirty kitchen wearing a bikini. In one early scene, Alice, alone in her bedroom, examines and touches her body in the mirror, changing into a hyper-babyish pyjama set. She then immediately vomits all over it once in bed. It’s like a corporeal rejection of what an audience expects when a young girl undresses in front of the camera (and has its comparable moment in Fat Girl, in the scene in which Anaïs lifts up her nightie in front of the mirror). The gaze, in A Real Young Girl, is always Alice’s herself. “Alice doesn’t do languid poses for the [male] photographer’s eye,” Breillat confirms. “She makes a devastating inventory of that body that’s blossoming and oozing from everywhere from her own, unforgiving eye.”

I Only Believe in Myself is especially revealing on the origins of 36 Fillette, Breillat’s third film. Known in English as Virgin or Junior Size 36, and based on her 1987 novel, it is the film that most closely maps onto the director’s own memories of girlhood: specifically, her survival of an attempted rape at the age of 14. In 36 Fillette, Lili (Delphine Zentout), who is holidaying with her family on the French coast, hitchhikes to a local disco where she meets a much older playboy. Breillat tells the anecdote the story is based on in the book’s first pages: a time when she thought “nightclubs were the most important thing in the world”, and she hitchhiked to one with her sister every night of the summer vacation. Like Lili, she met a man there (“very seductive, but already decaying”) and was convinced to go up to his hotel room one night. As adapted in 36 Fillette, the experience consists of a painfully drawn-out negotiation in which the man continues to pressure Lili into sex, and ends with her injuring him and escaping. (It’s during this sequence that we also see an early iteration of the girl’s fingers spread over her eyes that would become one of the most memorable stills of Fat Girl).

For Breillat, filming something deemed unfilmable is the essence of cinema – and is what makes it “not obscene.” But reading interviews with the director, it’s clear that most of what we find shocking in her work comes from inside the house. Breillat’s powerful memories of her actual girlhood give them their substance. That includes the violence of her real encounter as a 14-year-old, for instance, but also banal textures of girlhood’s dailiness: family fights, sitting in cafes, waiting around, waiting for the bus. Sometimes you could blink and be in an Éric Rohmer film (incidentally, Breillat sometimes drew on Rohmerienne dialogue to rehearse her actors). But in Rohmer’s modest films, the teenagers are contained; Breillat’s are caged creatures barking to be freed. But even among all their distressing events, Breillat’s endless summer vacations pay tribute to the space boredom offers – the way female adolescence “lets you dream, (and) create your own world that protects you from any conditioning”, as she states in I Only Believe in Myself.

Alice, Anaïs, Lili: even in their wildness, they have the self-possession of the not-yet-conditioned. It’s the other side of the coin of girlhood’s naivety: it brings the girls into extreme scenarios with men, but there is also a certain resilience in the “not-knowing-yet.” It’s the undomesticated energy of these teen-girl protagonists that is so enthralling; it’s what, as Breillat reveals, pulls her back to that time like an eternal return. “It’s my favourite cinematic subject!” she giggles about her tendency to only ever refer to “young girls”, rarely women. “I don’t know what a woman is!”

In the classic ‘rape revenge’ drama, a young woman seeks vengeance against her attacker, taking justice into her own hands. But the violence of Breillat’s movies, when it does occur, is never typically structured. These movies are, after all, very funny. And the men, at least in A Real Young Girl and 36 Fillette, are there to be laughed at. To be observed by us, in all their nudity and ridiculousness, and found wanting. Yes, the men pose a threat. But at the same time, in her filmmaking, Breillat twists them and makes their very masculinity seem small. She takes the glare of the shame she felt in her own girlhood – the one she mentioned to Rossellini – and throws it over men like a fluorescent overhead light.

Just think of the long, drawn-out seduction scene of 36 Fillette, inspired by the actual playboy who targeted Breillat as a girl. In it, Lili tells him off, and makes him absurd. “You wanna cut me in half, huh!”, she cries, calling him a pig as she throws on her jacket to leave. (According to the interview, Breillat said that in real life, too). We can see Breillat’s filmmaking in the same way: as a kind of “getting the final word”. The most memorable image of 36 Fillette, in the end, is the vivid smile Lili breaks into at the end of the film.

“The artistic act isn’t mannered, it’s violent, whether you like it or not.” The carnage of Breillat’s films – the violence, blood and sexual explicitness – renders them not suitable for girls of the age she is depicting. They are made, instead, for women for whom cinema has offered few total mirrors to our experience. As she puts it: “I’m a woman who started making cinema in an era when they talked about ‘women’s films’: delicateness, modesty and feminine refinement. And I wanted … scratch! A man’s thing.” There’s a reason all of us old young girls do not find Breillat’s films as ‘unwatchable’ as old young men. Because even at the extreme edge of what’s allowable, they are all a conversation with the unseen parts of ourselves.

I Only Believe in Myself. Somehow, I needed to hear that.

I Only Believe in Myself: Conversation with Murielle Joudet by Catherine Breillat is published by Semiotext(e) and is out now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.