Rewrite

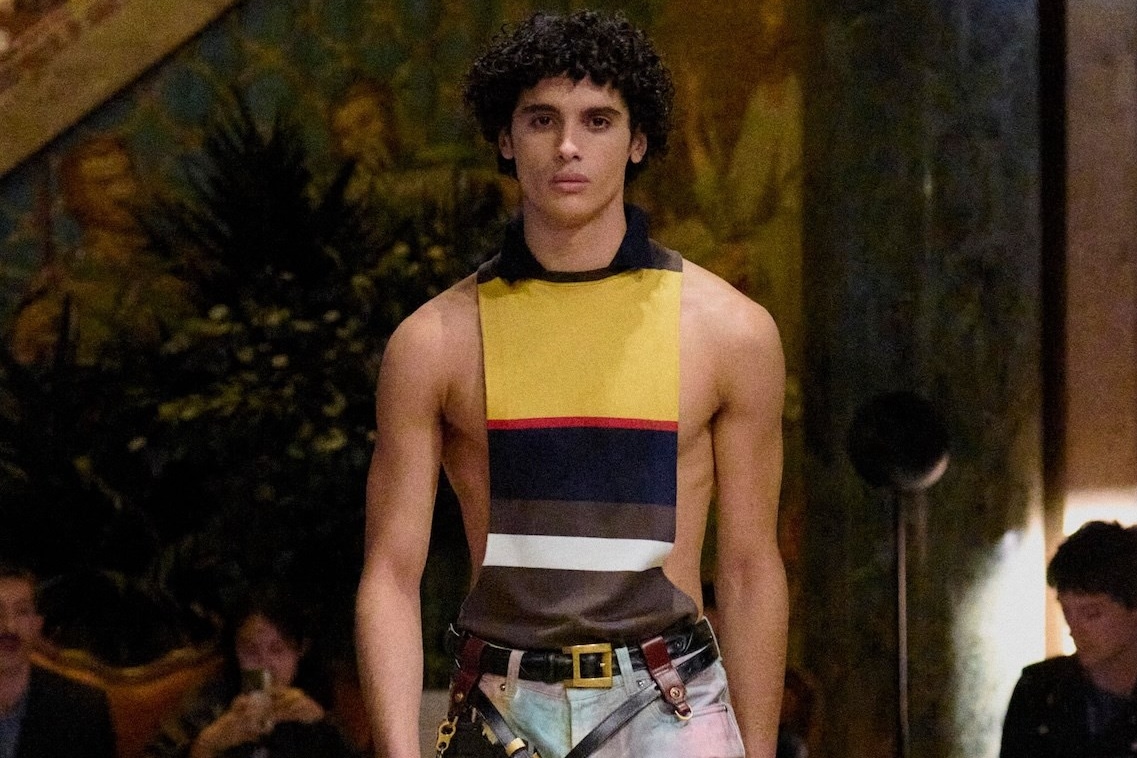

Lead ImageVersace Spring/Summer 2026Courtesy of Versace

To paraphrase The Sound of Music – possibly the least appropriate filmic reference ever, given the subject matter – how do you solve a problem like Versace? Actually, that’s rude. Versace isn’t a problem, it’s a fucking gem, a treasure, a vaulted palazzo ceiling of fat floating cherubs and cow-eyed gods and goddesses. It’s a Caravaggio painting, a Puccini opera. In short, an Italian masterpiece. But how do you tackle the problem of living up to the Versace legacy, and to the weight of its baggage – simultaneously fashionable, cultural, and emotional?

Only two people have had to answer that question. One is Donatella Versace, Gianni’s sister, former right-hand woman and until earlier this year, creative director of the label bearing their name. She herself sometimes struggled, with triumphs that at times equalled her brother’s work – when we’re talking about that dress, it could equally be Liz Hurley’s 1994 safety-pinned Gianni number, or Donatella’s racy, jungle-leafed slit-to-the-tit Jennifer Lopez dress, the original Internet-breaker. That’s a great legacy for Donatella to leave. She’s written her place in the fashion history books, and done her brother proud.

The second person to answer is Dario Vitale, Versace’s new creative director. And he isn’t unaware of the scale of the task at hand. He was born in 1983, five years after the foundation of the label – so he’s never not known it. And he’s Italian, which adds another layer, given that Gianni Versace was a national hero, basically beatified following his death in 1997. Donatella is something of a treasure too.

Here’s his plan for scaling the Sisyphean task of living up to those two Italian icons, season in and season out. “It’s the feeling of the legacy of Versace rather than the pieces themselves – the spirit of Versace,” Vitale said after his show, his voice clear above the hubbub of a thick scrum of journalists that recall the famously frenzied throngs that habitually surround his former employer, Miuccia Prada. Vitale had been pulling pieces from the archive, something Donatella had always been understandably loath to do – too heavy as they were with a personal rather than a professional history. Vitale could appreciate them as works of fashion, rather than fragments of a life ended too soon. Sometimes, distance helps.

The first example of this was the dress Vitale made for Julia Roberts to wear to the Venice Film Festival in August – a harlequin-embroidered evening gown that riffed back on op-art dresses Gianni designed for his winter 1986 show. In the opulent palazzo that Vitale borrowed for his debut, another version of that dress, in black beads and chocolate-brown silk, was casually tossed over a marble balustrade. It wasn’t apparent if it was old or new, which was kind of the point of the clothes he showed on warm bodies, too.

That said, Vitale didn’t base this collection – nor, it seems, his Versace as a whole – in analytical study. “Versace is almost like Coca-Cola,” he said. “I hope it doesn’t come across as offensive, but I knew it. It belongs to pop culture – I know it by heart.” So instead of a decorous redux of Versace’s greatest hits – by Gianni, or Donatella – Vitale worked off instinct, reflex. There was also a shunning of chronology, so ideas filched from Versace collections across the years – but, generally, spanning the first decade of Vitale’s own life, 1983-1993, I’d say – were combined in unexpected outfits. Casual, high-waisted striped jeans may be belted beneath a beaded, Atelier Versace-esque brassiere, a pair of nasty cone-heel satin pumps underfoot. A single floral embroidered glove might accompany hiked-up pants, a baroque-n-roll studded leather vest, and a grey marl knit. Roberts’ dress emerged chopped short in different colour ways. The menswear was pure himbo, part Versace men without ties, part the Tom, Dick and Harry that manservanted Isabella Rossellini’s Lisle Von Rhuman in Death Becomes Her. That’s a very specific reference, but those Fabio-ish beefcakes were very, very Versace.

The interesting thing here was that the elements were all Versace, but the mix shouldn’t have been. And yet, somehow, it was. That’s probably because, at the core of it all, was a throb of sex appeal that sat underneath everything Gianni himself undertook. Remember, Versace referenced that high Renaissance art next to the attire of sadomasochist dungeons, classical gods crossed with the sex workers that paraded past his childhood home in Reggio Calabria. To the young Gianni, their clothes were so much more appealing than the ones knocked up for the local bourgeoisie by his mother, the town’s dressmaker. Incidentally, Vitale’s mother wore Versace, he said. And when it comes to sex, he wanted to open a dialogue rather than answer definitively. “What is sexy?” he posited backstage. “We will never get an answer, so we’ll keep on trying.”

Sexy at this Versace was, actually, pretty hardcore. The crotches of some of the trousers were left open; the backs of dresses scooped low or slit entirely to reveal flashes of Versace underwear, and the menswear, especially, was spliced out and meatily crotched. But rather than a performative, staged sexuality, this all felt real. And – most importantly of all – relevant.

Gianni Versace and Giorgio Armani were once fashion foes, in the rich old Italian tradition of the Medici and Sforzas – rival camps, battling it out for control of the landscape. Following the death of Giorgio Armani earlier this month, succession plans must be afoot. They’d do well to glance sideways at their old antagonists, to see what’s going on with Vitale at Versace. They’re getting it right.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageVersace Spring/Summer 2026Courtesy of Versace

To paraphrase The Sound of Music – possibly the least appropriate filmic reference ever, given the subject matter – how do you solve a problem like Versace? Actually, that’s rude. Versace isn’t a problem, it’s a fucking gem, a treasure, a vaulted palazzo ceiling of fat floating cherubs and cow-eyed gods and goddesses. It’s a Caravaggio painting, a Puccini opera. In short, an Italian masterpiece. But how do you tackle the problem of living up to the Versace legacy, and to the weight of its baggage – simultaneously fashionable, cultural, and emotional?

Only two people have had to answer that question. One is Donatella Versace, Gianni’s sister, former right-hand woman and until earlier this year, creative director of the label bearing their name. She herself sometimes struggled, with triumphs that at times equalled her brother’s work – when we’re talking about that dress, it could equally be Liz Hurley’s 1994 safety-pinned Gianni number, or Donatella’s racy, jungle-leafed slit-to-the-tit Jennifer Lopez dress, the original Internet-breaker. That’s a great legacy for Donatella to leave. She’s written her place in the fashion history books, and done her brother proud.

The second person to answer is Dario Vitale, Versace’s new creative director. And he isn’t unaware of the scale of the task at hand. He was born in 1983, five years after the foundation of the label – so he’s never not known it. And he’s Italian, which adds another layer, given that Gianni Versace was a national hero, basically beatified following his death in 1997. Donatella is something of a treasure too.

Here’s his plan for scaling the Sisyphean task of living up to those two Italian icons, season in and season out. “It’s the feeling of the legacy of Versace rather than the pieces themselves – the spirit of Versace,” Vitale said after his show, his voice clear above the hubbub of a thick scrum of journalists that recall the famously frenzied throngs that habitually surround his former employer, Miuccia Prada. Vitale had been pulling pieces from the archive, something Donatella had always been understandably loath to do – too heavy as they were with a personal rather than a professional history. Vitale could appreciate them as works of fashion, rather than fragments of a life ended too soon. Sometimes, distance helps.

The first example of this was the dress Vitale made for Julia Roberts to wear to the Venice Film Festival in August – a harlequin-embroidered evening gown that riffed back on op-art dresses Gianni designed for his winter 1986 show. In the opulent palazzo that Vitale borrowed for his debut, another version of that dress, in black beads and chocolate-brown silk, was casually tossed over a marble balustrade. It wasn’t apparent if it was old or new, which was kind of the point of the clothes he showed on warm bodies, too.

That said, Vitale didn’t base this collection – nor, it seems, his Versace as a whole – in analytical study. “Versace is almost like Coca-Cola,” he said. “I hope it doesn’t come across as offensive, but I knew it. It belongs to pop culture – I know it by heart.” So instead of a decorous redux of Versace’s greatest hits – by Gianni, or Donatella – Vitale worked off instinct, reflex. There was also a shunning of chronology, so ideas filched from Versace collections across the years – but, generally, spanning the first decade of Vitale’s own life, 1983-1993, I’d say – were combined in unexpected outfits. Casual, high-waisted striped jeans may be belted beneath a beaded, Atelier Versace-esque brassiere, a pair of nasty cone-heel satin pumps underfoot. A single floral embroidered glove might accompany hiked-up pants, a baroque-n-roll studded leather vest, and a grey marl knit. Roberts’ dress emerged chopped short in different colour ways. The menswear was pure himbo, part Versace men without ties, part the Tom, Dick and Harry that manservanted Isabella Rossellini’s Lisle Von Rhuman in Death Becomes Her. That’s a very specific reference, but those Fabio-ish beefcakes were very, very Versace.

The interesting thing here was that the elements were all Versace, but the mix shouldn’t have been. And yet, somehow, it was. That’s probably because, at the core of it all, was a throb of sex appeal that sat underneath everything Gianni himself undertook. Remember, Versace referenced that high Renaissance art next to the attire of sadomasochist dungeons, classical gods crossed with the sex workers that paraded past his childhood home in Reggio Calabria. To the young Gianni, their clothes were so much more appealing than the ones knocked up for the local bourgeoisie by his mother, the town’s dressmaker. Incidentally, Vitale’s mother wore Versace, he said. And when it comes to sex, he wanted to open a dialogue rather than answer definitively. “What is sexy?” he posited backstage. “We will never get an answer, so we’ll keep on trying.”

Sexy at this Versace was, actually, pretty hardcore. The crotches of some of the trousers were left open; the backs of dresses scooped low or slit entirely to reveal flashes of Versace underwear, and the menswear, especially, was spliced out and meatily crotched. But rather than a performative, staged sexuality, this all felt real. And – most importantly of all – relevant.

Gianni Versace and Giorgio Armani were once fashion foes, in the rich old Italian tradition of the Medici and Sforzas – rival camps, battling it out for control of the landscape. Following the death of Giorgio Armani earlier this month, succession plans must be afoot. They’d do well to glance sideways at their old antagonists, to see what’s going on with Vitale at Versace. They’re getting it right.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.