Rewrite

Lead ImageVirgil Abloh takes bow at the close of his first Louis Vuitton Men’s collection, 2018Photography by Jonas Gustavsson. Courtesy of Penguin Books

When the late fashion designer Virgil Abloh first saw Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ, it triggered an epiphany. An engineering student at the time, Abloh marvelled at the notion that an artist could alter the course of history with a single innovation. That kind of stratospheric, culture-shifting impact is something Abloh would accomplish in his short lifetime.

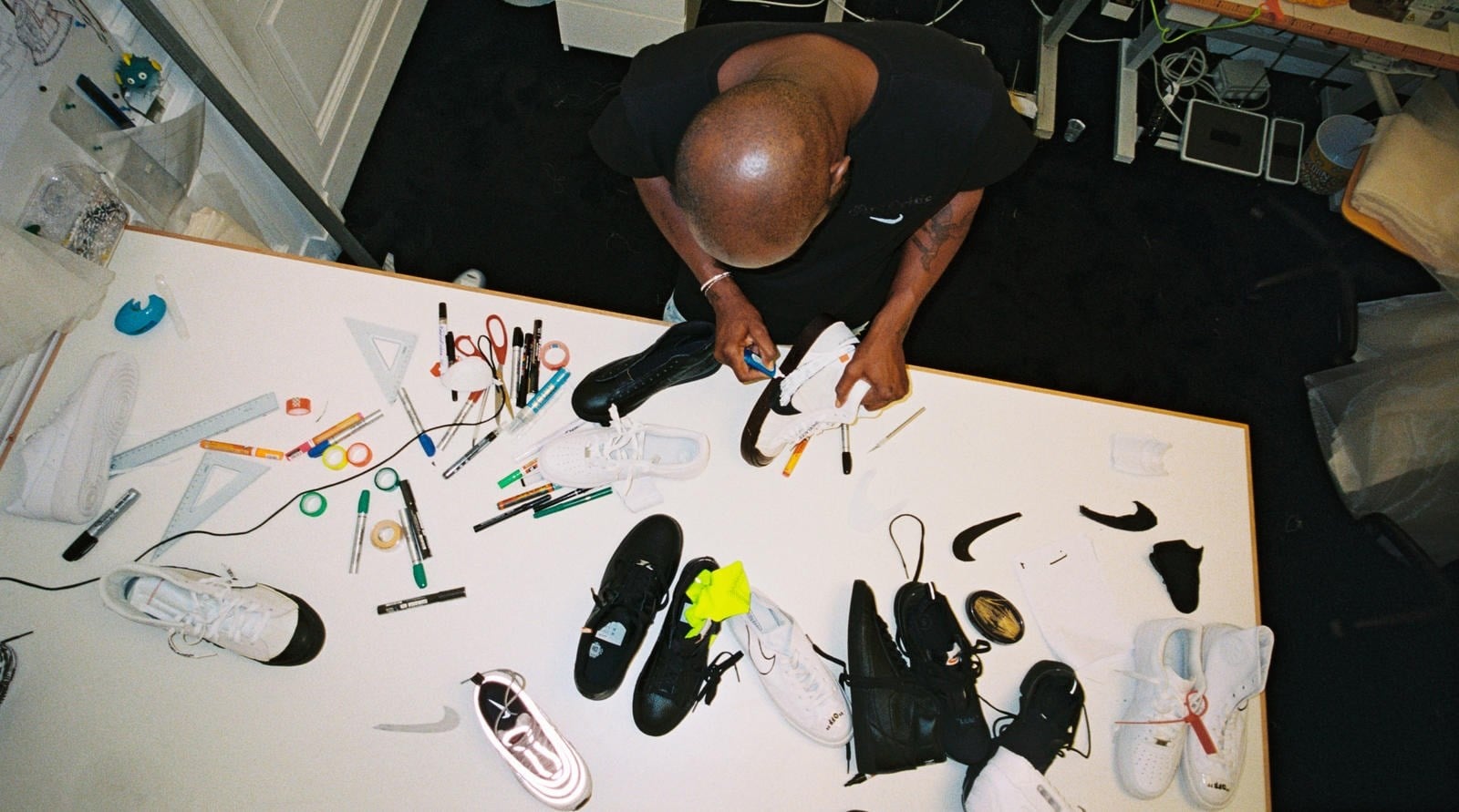

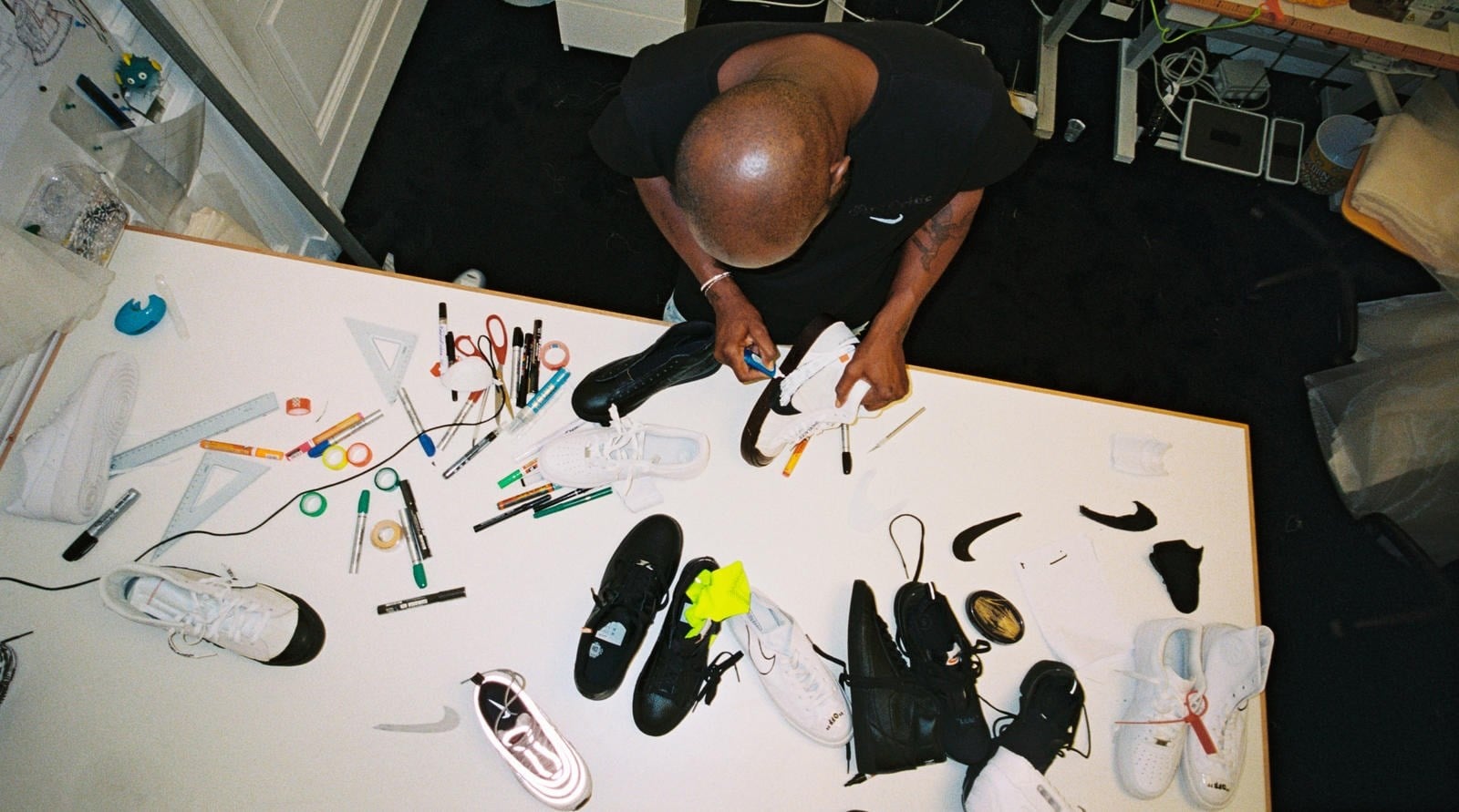

Once described as ‘the Warhol of our time’, Abloh’s dynamic practice spanned DJing, furniture making, and creative direction. He studied architecture (as did a long list of trailblazers in fashion, including Tom Ford, Raf Simons, Thierry Mugler, and Rei Kawakubo), which drove his understanding of and approach to design. Under his label Off-White, he created a number of iconic designs and collaborated with Kanye West, Ikea, and Nike. In 2015, he received an LVMH Prize nomination for Best New Designer, and in 2017, a British Fashion Award. He capped off these achievements in 2018 with an appointment at Louis Vuitton as artistic director of its menswear line.

Abloh’s philosophy has forever left an imprint on fashion and design, from his controversial three per cent approach (the idea that one only needs to alter something by three per cent in order to create something new) and unabashed love of irony, to his comfort with appropriation and insistence that streetwear is a form of art. He was obsessed with finding – and working from – a place where both “the tourist” and “the purist” could meet, a zone of openness and rigorous play.

In her new book Make it Ours: Crashing the Gates of Culture with Virgil Abloh, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Robin Givhan chronicles Abloh’s ascent to the heights of the fashion world. Givhan tracks pivotal moments in Abloh’s journey alongside the major cultural events and transformations in fashion, music, and politics that allowed him to take centre stage. Particularly insightful is her research on Abloh’s forbearers – Black designers such as Ozwald Boateng, Edward Buchanan, Gordon Henderson, and Patrick Kelly – who paved the way for Abloh. Make it Ours is a fascinating deep-dive into how fashion has evolved throughout the 21st century, as well as the rise and continued influence of streetwear.

Here, Robin Givhan speaks on Make It Ours and the lasting cultural impact of the late designer.

Elodie Saint-Louis: What made you want to write a book about Virgil, and why now?

Robin Givhan: I feel like there’s this bell curve of fans: the ones who really looked at him as this iconic, game-changing figure, and others who felt very concerned about the way that he approached creativity and copyright. The idea of changing something by three per cent to make it completely new … it interested me that those two things were really in tension when it came to his legacy.

When he passed away, I recognised the deeply intimate emotions people felt and wanted to explore that. But you never really know what the circumstances [are] going to be when the book actually goes out into the world. It is arriving at a time that is making it more impactful because so many of the topics that are addressed in the book really come down to cultural narratives and who’s in charge of them. I think we’re in the midst of that whole conversation right now as a country.

ESL: Virgil really embodied flipping those structures on their head. We’re in this moment where we’re experiencing a lot of backlash around DEI. What’s your sense of where we’re at today?

RG: In some ways, the lesson that I took from the book was about the power of optimism. It’s not about being naive or putting your head in the sand or ignoring what’s going on. It’s actively choosing to believe that things can change, things can be better, people can be better.

I’m going to stay neutral on the lessons that corporations learned as entities, because I do think that, to some degree, corporations didn’t take the full nuance or the thoughtful lessons of Virgil’s success. I think the lesson that they really took was, if you hire somebody who has tentacles in all these other parts of the culture, they can bring that to your brand. I think they missed the sense of Virgil as this outsider, Virgil as this person who wanted to be very transparent, who wanted to break down the walls and help people really see inside the industry. I think that got lost, unfortunately.

“The lesson that I took from the book was about the power of optimism. It’s actively choosing to believe that things can change” – Robin Givhan

ESL: What was it about Virgil that was so transformative? A big comparison you make throughout the book is between him and Kanye.

RG: Those first ten years of [Kanye’s] career, there was such creativity and ambition and optimism and sense of possibility. Virgil met Kanye during those early years, he had just come off of College Dropout. Kanye really wanted to build a fashion brand and it was just a cyclone of creative energy. Virgil certainly benefited from that.

But, and Virgil talked a bit about this, he was the accessible one, the one with the open arms, welcoming people in. Even then, Kanye could be very mercurial. He could be difficult and unpredictable. As I was doing interviews for the book, people talked so much about Virgil’s temperament. They talked about what a nice person he was. They talked about how he had such an even keel. How they rarely, if ever, saw him express public anger or be ill-tempered. I think some of that was Virgil’s nature. I also think some of it came from a sense of confidence and his ability and focus. It was one of the things that he got called out on the carpet for later, during the Black Lives Matter protests. He was very much a centrist when it came to how you deal with issues related to race or prejudice, or assumptions. He was very, “I’m not out here to turn over tables. I’ve got my eye focused on where I want to go.”

ESL: Did you discover anything surprising while interviewing people for the book?

RG: I was fascinated by how many layers there were to the simple fact that people describe him as the son of Ghanaian immigrants. That was always the phrase. I found it so interesting that he was never referred to as just African American, which would have been equally as accurate. I remember asking someone whose parents were Ghanaian, “Did your parents ever say you have to be twice as good to get just as far?” He told me, “No, the expectation is that you already know you’re twice as good.” With Virgil, that comes through sometimes in the audacity of his asks.

I was surprised when Julie Gilhart told me that Virgil had said to her, “I want Givenchy. Who do I talk to to get the Givenchy job?” She was knocked off her heels because frankly, she just didn’t think he was qualified. She said later, in hindsight, it was just a failure of her imagination. He didn’t have the qualifications she was used to, but it didn’t mean the qualifications that he had weren’t as valuable. He saw them as valuable. That’s such an audacious and admirable way to be. It wasn’t hubris, it was just, “Yeah, I know I’m great. So why shouldn’t I be up for this job?”

“I don’t want to say that Virgil was inevitable, but I think the circumstances were such that someone akin to Virgil was inevitable. He was the one who had the talent and the wherewithal” – Robin Givhan

ESL: Did you ever meet Virgil?

RG: The first time I met him is when he was up for the LVMH Prize. There was a bit of a scram of media around his cubicle. Kanye was there and was pulling things out and talking about how great Virgil was, really hyping him up. He was just this very calm – I don’t want to say unassuming – quiet water in the midst of the waves of commotion that Kanye was causing. It was very much about engaging with the fashion industry, not putting himself above it or outside of it.

ESL: Did you ever have a chance to see any of his shows in person?

RV: Yes. One show in particular [stands out] – it was 2018, just before he got the Louis Vuitton appointment. It was his women’s show in this event space in the centre of Paris. Earlier in the day, Virgil had done a sneaker event and he had dropped on his Instagram, “Hey, I’m having a show. Y’all come.” Which is not what a designer typically does. There was this massive crush of sneakerheads who decided to come and see the show without an actual invitation or seat.

ESL: It sounds like people were just really excited to be there.

RG: It was a combination of fans and industry people who were looking at it from a critical perspective. I think their reactions were much more nuanced and complicated. Virgil was, for instance, a huge fan of Raf Simons. And Raf was quoted as saying, “I think Virgil is a really nice guy.” But he didn’t have a lot of complimentary things to say about the collections because he felt that they were derivative. Virgil’s response to that was basically, “I’m still a huge Raf Simons fan.”

ESL: Has your opinion of Virgil changed since writing the book?

RG: [The book] showed me the way fashion was leading up to this moment. When you’re in the midst of it, it’s impossible to see what the ramifications are going to be ten years down the road. I don’t want to say that Virgil was inevitable, but I think the circumstances were such that someone akin to Virgil was inevitable. He was the one who had the talent and the wherewithal to step onto that ground and flourish.

Make it Ours: Crashing the Gates of Culture by Robin Givhan is published by Penguin and is out now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageVirgil Abloh takes bow at the close of his first Louis Vuitton Men’s collection, 2018Photography by Jonas Gustavsson. Courtesy of Penguin Books

When the late fashion designer Virgil Abloh first saw Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ, it triggered an epiphany. An engineering student at the time, Abloh marvelled at the notion that an artist could alter the course of history with a single innovation. That kind of stratospheric, culture-shifting impact is something Abloh would accomplish in his short lifetime.

Once described as ‘the Warhol of our time’, Abloh’s dynamic practice spanned DJing, furniture making, and creative direction. He studied architecture (as did a long list of trailblazers in fashion, including Tom Ford, Raf Simons, Thierry Mugler, and Rei Kawakubo), which drove his understanding of and approach to design. Under his label Off-White, he created a number of iconic designs and collaborated with Kanye West, Ikea, and Nike. In 2015, he received an LVMH Prize nomination for Best New Designer, and in 2017, a British Fashion Award. He capped off these achievements in 2018 with an appointment at Louis Vuitton as artistic director of its menswear line.

Abloh’s philosophy has forever left an imprint on fashion and design, from his controversial three per cent approach (the idea that one only needs to alter something by three per cent in order to create something new) and unabashed love of irony, to his comfort with appropriation and insistence that streetwear is a form of art. He was obsessed with finding – and working from – a place where both “the tourist” and “the purist” could meet, a zone of openness and rigorous play.

In her new book Make it Ours: Crashing the Gates of Culture with Virgil Abloh, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Robin Givhan chronicles Abloh’s ascent to the heights of the fashion world. Givhan tracks pivotal moments in Abloh’s journey alongside the major cultural events and transformations in fashion, music, and politics that allowed him to take centre stage. Particularly insightful is her research on Abloh’s forbearers – Black designers such as Ozwald Boateng, Edward Buchanan, Gordon Henderson, and Patrick Kelly – who paved the way for Abloh. Make it Ours is a fascinating deep-dive into how fashion has evolved throughout the 21st century, as well as the rise and continued influence of streetwear.

Here, Robin Givhan speaks on Make It Ours and the lasting cultural impact of the late designer.

Elodie Saint-Louis: What made you want to write a book about Virgil, and why now?

Robin Givhan: I feel like there’s this bell curve of fans: the ones who really looked at him as this iconic, game-changing figure, and others who felt very concerned about the way that he approached creativity and copyright. The idea of changing something by three per cent to make it completely new … it interested me that those two things were really in tension when it came to his legacy.

When he passed away, I recognised the deeply intimate emotions people felt and wanted to explore that. But you never really know what the circumstances [are] going to be when the book actually goes out into the world. It is arriving at a time that is making it more impactful because so many of the topics that are addressed in the book really come down to cultural narratives and who’s in charge of them. I think we’re in the midst of that whole conversation right now as a country.

ESL: Virgil really embodied flipping those structures on their head. We’re in this moment where we’re experiencing a lot of backlash around DEI. What’s your sense of where we’re at today?

RG: In some ways, the lesson that I took from the book was about the power of optimism. It’s not about being naive or putting your head in the sand or ignoring what’s going on. It’s actively choosing to believe that things can change, things can be better, people can be better.

I’m going to stay neutral on the lessons that corporations learned as entities, because I do think that, to some degree, corporations didn’t take the full nuance or the thoughtful lessons of Virgil’s success. I think the lesson that they really took was, if you hire somebody who has tentacles in all these other parts of the culture, they can bring that to your brand. I think they missed the sense of Virgil as this outsider, Virgil as this person who wanted to be very transparent, who wanted to break down the walls and help people really see inside the industry. I think that got lost, unfortunately.

“The lesson that I took from the book was about the power of optimism. It’s actively choosing to believe that things can change” – Robin Givhan

ESL: What was it about Virgil that was so transformative? A big comparison you make throughout the book is between him and Kanye.

RG: Those first ten years of [Kanye’s] career, there was such creativity and ambition and optimism and sense of possibility. Virgil met Kanye during those early years, he had just come off of College Dropout. Kanye really wanted to build a fashion brand and it was just a cyclone of creative energy. Virgil certainly benefited from that.

But, and Virgil talked a bit about this, he was the accessible one, the one with the open arms, welcoming people in. Even then, Kanye could be very mercurial. He could be difficult and unpredictable. As I was doing interviews for the book, people talked so much about Virgil’s temperament. They talked about what a nice person he was. They talked about how he had such an even keel. How they rarely, if ever, saw him express public anger or be ill-tempered. I think some of that was Virgil’s nature. I also think some of it came from a sense of confidence and his ability and focus. It was one of the things that he got called out on the carpet for later, during the Black Lives Matter protests. He was very much a centrist when it came to how you deal with issues related to race or prejudice, or assumptions. He was very, “I’m not out here to turn over tables. I’ve got my eye focused on where I want to go.”

ESL: Did you discover anything surprising while interviewing people for the book?

RG: I was fascinated by how many layers there were to the simple fact that people describe him as the son of Ghanaian immigrants. That was always the phrase. I found it so interesting that he was never referred to as just African American, which would have been equally as accurate. I remember asking someone whose parents were Ghanaian, “Did your parents ever say you have to be twice as good to get just as far?” He told me, “No, the expectation is that you already know you’re twice as good.” With Virgil, that comes through sometimes in the audacity of his asks.

I was surprised when Julie Gilhart told me that Virgil had said to her, “I want Givenchy. Who do I talk to to get the Givenchy job?” She was knocked off her heels because frankly, she just didn’t think he was qualified. She said later, in hindsight, it was just a failure of her imagination. He didn’t have the qualifications she was used to, but it didn’t mean the qualifications that he had weren’t as valuable. He saw them as valuable. That’s such an audacious and admirable way to be. It wasn’t hubris, it was just, “Yeah, I know I’m great. So why shouldn’t I be up for this job?”

“I don’t want to say that Virgil was inevitable, but I think the circumstances were such that someone akin to Virgil was inevitable. He was the one who had the talent and the wherewithal” – Robin Givhan

ESL: Did you ever meet Virgil?

RG: The first time I met him is when he was up for the LVMH Prize. There was a bit of a scram of media around his cubicle. Kanye was there and was pulling things out and talking about how great Virgil was, really hyping him up. He was just this very calm – I don’t want to say unassuming – quiet water in the midst of the waves of commotion that Kanye was causing. It was very much about engaging with the fashion industry, not putting himself above it or outside of it.

ESL: Did you ever have a chance to see any of his shows in person?

RV: Yes. One show in particular [stands out] – it was 2018, just before he got the Louis Vuitton appointment. It was his women’s show in this event space in the centre of Paris. Earlier in the day, Virgil had done a sneaker event and he had dropped on his Instagram, “Hey, I’m having a show. Y’all come.” Which is not what a designer typically does. There was this massive crush of sneakerheads who decided to come and see the show without an actual invitation or seat.

ESL: It sounds like people were just really excited to be there.

RG: It was a combination of fans and industry people who were looking at it from a critical perspective. I think their reactions were much more nuanced and complicated. Virgil was, for instance, a huge fan of Raf Simons. And Raf was quoted as saying, “I think Virgil is a really nice guy.” But he didn’t have a lot of complimentary things to say about the collections because he felt that they were derivative. Virgil’s response to that was basically, “I’m still a huge Raf Simons fan.”

ESL: Has your opinion of Virgil changed since writing the book?

RG: [The book] showed me the way fashion was leading up to this moment. When you’re in the midst of it, it’s impossible to see what the ramifications are going to be ten years down the road. I don’t want to say that Virgil was inevitable, but I think the circumstances were such that someone akin to Virgil was inevitable. He was the one who had the talent and the wherewithal to step onto that ground and flourish.

Make it Ours: Crashing the Gates of Culture by Robin Givhan is published by Penguin and is out now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.