Rewrite

To mark a major new retrospective at the BFI, we present our picks from one of modern European cinema’s most shocking and masterful oeuvres

Michael Haneke was born in Austria 1942, growing up through one of the most fraught periods of contemporary Europe’s history. A filmmaker of formal minimalism and rich thematic interests, Haneke made a name for himself with controversial commentaries on the relationship between violence and image-making (Benny’s Video, Funny Games and its English-language remake). But his reputation as one of his generation’s finest filmmakers was cemented with a series of psychological dramas connecting the tensions of romantic and familial relationships with a deep societal malaise. Never sentimental or polemic, they explore the pain people thrust onto one another in order to feel more secure.

With the re-release of The Piano Teacher and Hidden in cinemas this month, Curzon and BFI have compiled Complicit, a thorough retrospective of Haneke’s work tracing his dramas for West German and Austrian television through his pre-millennium ‘glaciation trilogy’ of European social disintegration, culminating with his major works of the 21st century, including The White Ribbon and Amour. To prime you (but maybe not prepare you) for the visceral and uncompromising work of a European master, AnOther has selected a range of highlights that confront us with the shared destructive urges and apathy of our world.

Haneke’s deeply upsetting debut feature breaks open the full, terrifying potential of his themes across 111 elliptical minutes, during which the hidden but certain violence of modern European malaise is unveiled. Over a three-year period, a middle-class Austrian couple wear out their mundane domestic routines and dryly decide to destroy their lives with their young daughter in tow. Even if you can’t read between the lines of Haneke’s deliberate and ominous buildup in the first half, then the moment of unified, fatalistic certainty shared by the small family inside an automated carwash confirms the abject terror of what’s to come.

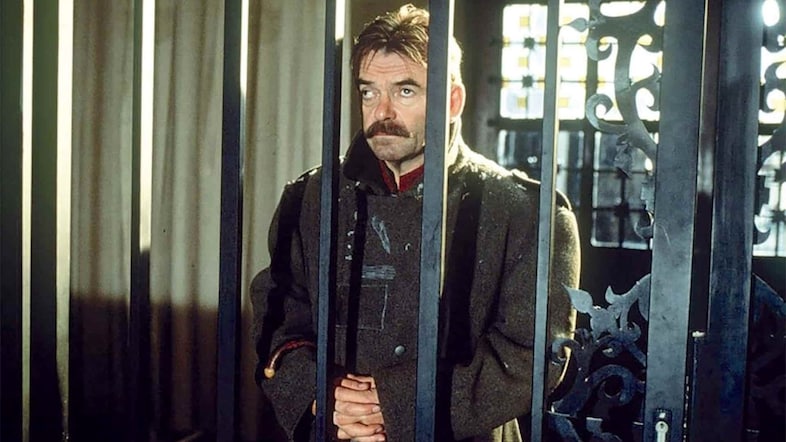

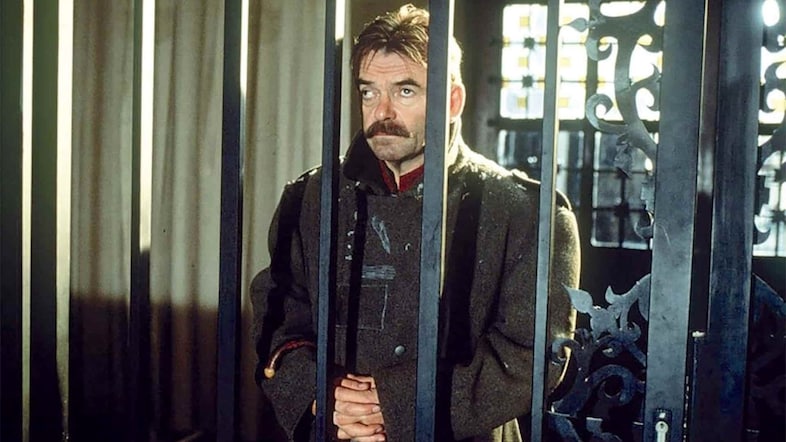

Even though Michael Haneke directed for television before graduating to theatrical distribution, this TV film adaptation of Joseph Roth’s novel followed up his second film, the controversial Benny’s Video. Die Rebellion is a tragic tale from the interwar period about Andreas Pum (Branko Samarovski), an amputee whose acceptance of his compromised position as a disabled veteran in the first Austrian republic does not protect him from bureaucratic hostility and ableism. Haneke’s trademark minimalist editing and austere compositions are intact on the small screen, but there’s an economic simplicity with the TV form that amplifies the tragedy of Andreas’ resilience. By sticking close to his style, Haneke’s film avoids exaggerated sentimentality, making strong use of a novelistic narrator who speaks plainly but astutely about an unstable society that paved the way for Nazism.

Haneke’s masterwork dedicates itself to thorny and uncomfortable questions about self-harm, interrogating pain as a valve for alleviating inner suffering. It stars a career-defining Isabelle Huppert as Erika, a rigid, wounded and repressed piano teacher who pursues and thwarts in equal measure her own sexual satisfaction. Erika is tempted by a taboo relationship with her amorous student Walter (Benoît Magimel), but her asphyxiating Electra complex and rigid sexual demands trigger waves of shame and resentment that Haneke navigates with expert empathy and scrutiny. Nothing about The Piano Teacher – especially its shocking violence – is easy to swallow, but Haneke’s melodrama excels as an unsparing dissection of a very human pain.

One of Haneke’s most divisive films, Time of the Wolf is an apocalyptic story that is both incredibly direct and typically evasive. When a cataclysmic event drives city dwellers into the eerie, hostile countryside, a mother (Isabelle Huppert) and her two children confront the inherent individualism of survival in a suitably unsparing and Hanekian fashion. Time of the Wolf follows its miserable but astute line of questioning without wavering for its near-two-hour runtime, risking didacticism more than his dramas in order to maintain a strict focus on his anxieties about societal violence. Can a culture made up of self-dependent and hierarchical units hope to survive at society’s collapse? Does surviving without collectivity and community even resemble ‘survival’? And eventually, how does hope manifest?

The masculine double to The Piano Teacher’s treatise on repressed desire, Hidden (also known as Caché) capitalises on the latent dread of seeing our lives reflected back to us on the grainy fabric of videotape. A middle-class Parisian couple (Daniel Auteuil and Juliette Binoche) are suddenly implicated by the inexplicable appearance of handmade surveillance tapes of their home. As the 50-something husband lashes out against the creeping sense of guilt provoked by these subtly metaphysical missives, Haneke mines the contradictions of Europe distancing itself from the colonial atrocities of recent history – the result is a portrait of flailing ego against a backdrop of barely concealed societal violence. Hidden is a textbook example of his beguiling dramatic structure – akin to opening a wound and inspecting it past the point of the onlooker’s comfort, refusing to stitch it back up again.

One of the most confronting 21st-century texts on Nazi psychology and a clear antecedent to Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest (both films share a lead actor, Christian Friedel), The White Ribbon is a monochromatic examination of the abusive conditions of a traditional Protestant German village leading up to the first world war. Sheltered by upstanding domestic privacy, parents impose their authority on their offspring as acts of anonymous barbarity crop up around the village, all connected to figures of patriarchal power. The White Ribbon isn’t so much a mystery as an exercise in historical pattern recognition: the children’s cruelty is charged with a fraught sense of rebellion that, even though Haneke deploys a trademark unresolved ending before the breakout of war, we know will assure an entire generation that they will be rewarded for punitive mob violence.

Complicit: The Films of Michael Haneke is at BFI throughout June.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

To mark a major new retrospective at the BFI, we present our picks from one of modern European cinema’s most shocking and masterful oeuvres

Michael Haneke was born in Austria 1942, growing up through one of the most fraught periods of contemporary Europe’s history. A filmmaker of formal minimalism and rich thematic interests, Haneke made a name for himself with controversial commentaries on the relationship between violence and image-making (Benny’s Video, Funny Games and its English-language remake). But his reputation as one of his generation’s finest filmmakers was cemented with a series of psychological dramas connecting the tensions of romantic and familial relationships with a deep societal malaise. Never sentimental or polemic, they explore the pain people thrust onto one another in order to feel more secure.

With the re-release of The Piano Teacher and Hidden in cinemas this month, Curzon and BFI have compiled Complicit, a thorough retrospective of Haneke’s work tracing his dramas for West German and Austrian television through his pre-millennium ‘glaciation trilogy’ of European social disintegration, culminating with his major works of the 21st century, including The White Ribbon and Amour. To prime you (but maybe not prepare you) for the visceral and uncompromising work of a European master, AnOther has selected a range of highlights that confront us with the shared destructive urges and apathy of our world.

Haneke’s deeply upsetting debut feature breaks open the full, terrifying potential of his themes across 111 elliptical minutes, during which the hidden but certain violence of modern European malaise is unveiled. Over a three-year period, a middle-class Austrian couple wear out their mundane domestic routines and dryly decide to destroy their lives with their young daughter in tow. Even if you can’t read between the lines of Haneke’s deliberate and ominous buildup in the first half, then the moment of unified, fatalistic certainty shared by the small family inside an automated carwash confirms the abject terror of what’s to come.

Even though Michael Haneke directed for television before graduating to theatrical distribution, this TV film adaptation of Joseph Roth’s novel followed up his second film, the controversial Benny’s Video. Die Rebellion is a tragic tale from the interwar period about Andreas Pum (Branko Samarovski), an amputee whose acceptance of his compromised position as a disabled veteran in the first Austrian republic does not protect him from bureaucratic hostility and ableism. Haneke’s trademark minimalist editing and austere compositions are intact on the small screen, but there’s an economic simplicity with the TV form that amplifies the tragedy of Andreas’ resilience. By sticking close to his style, Haneke’s film avoids exaggerated sentimentality, making strong use of a novelistic narrator who speaks plainly but astutely about an unstable society that paved the way for Nazism.

Haneke’s masterwork dedicates itself to thorny and uncomfortable questions about self-harm, interrogating pain as a valve for alleviating inner suffering. It stars a career-defining Isabelle Huppert as Erika, a rigid, wounded and repressed piano teacher who pursues and thwarts in equal measure her own sexual satisfaction. Erika is tempted by a taboo relationship with her amorous student Walter (Benoît Magimel), but her asphyxiating Electra complex and rigid sexual demands trigger waves of shame and resentment that Haneke navigates with expert empathy and scrutiny. Nothing about The Piano Teacher – especially its shocking violence – is easy to swallow, but Haneke’s melodrama excels as an unsparing dissection of a very human pain.

One of Haneke’s most divisive films, Time of the Wolf is an apocalyptic story that is both incredibly direct and typically evasive. When a cataclysmic event drives city dwellers into the eerie, hostile countryside, a mother (Isabelle Huppert) and her two children confront the inherent individualism of survival in a suitably unsparing and Hanekian fashion. Time of the Wolf follows its miserable but astute line of questioning without wavering for its near-two-hour runtime, risking didacticism more than his dramas in order to maintain a strict focus on his anxieties about societal violence. Can a culture made up of self-dependent and hierarchical units hope to survive at society’s collapse? Does surviving without collectivity and community even resemble ‘survival’? And eventually, how does hope manifest?

The masculine double to The Piano Teacher’s treatise on repressed desire, Hidden (also known as Caché) capitalises on the latent dread of seeing our lives reflected back to us on the grainy fabric of videotape. A middle-class Parisian couple (Daniel Auteuil and Juliette Binoche) are suddenly implicated by the inexplicable appearance of handmade surveillance tapes of their home. As the 50-something husband lashes out against the creeping sense of guilt provoked by these subtly metaphysical missives, Haneke mines the contradictions of Europe distancing itself from the colonial atrocities of recent history – the result is a portrait of flailing ego against a backdrop of barely concealed societal violence. Hidden is a textbook example of his beguiling dramatic structure – akin to opening a wound and inspecting it past the point of the onlooker’s comfort, refusing to stitch it back up again.

One of the most confronting 21st-century texts on Nazi psychology and a clear antecedent to Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest (both films share a lead actor, Christian Friedel), The White Ribbon is a monochromatic examination of the abusive conditions of a traditional Protestant German village leading up to the first world war. Sheltered by upstanding domestic privacy, parents impose their authority on their offspring as acts of anonymous barbarity crop up around the village, all connected to figures of patriarchal power. The White Ribbon isn’t so much a mystery as an exercise in historical pattern recognition: the children’s cruelty is charged with a fraught sense of rebellion that, even though Haneke deploys a trademark unresolved ending before the breakout of war, we know will assure an entire generation that they will be rewarded for punitive mob violence.

Complicit: The Films of Michael Haneke is at BFI throughout June.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.