Rewrite

As Caught Stealing arrives in UK cinemas, we examine one of contemporary Hollywood’s most disturbing and divisive oeuvres

If there is a rule to Darren Aronofsky’s work, it is that any given film from his nine feature-strong oeuvre will be a gruelling watch. Never going easy on the grossness, toe-stubbing, head-drilling, anguish and misery – whether a sweeping Biblical epic (Noah) or a tightly wound ballerina tragedy (Black Swan) – Aronofsky has cemented his status as one of contemporary cinema’s most divisive directors. Part of the reason behind his stylistic audacity could be sheer confidence or fear-dissolving ambition: the now 56-year-old director founded his own production company straight after making his student graduation film, aged 28.

First crashing on to the film festival circuit in 1998 as his head-turning debut Pi premiered at Sundance, Aronofsky has been an explosive presence ever since. His work is often met with torrid debate (as well as, occasionally, censorship or bans), the accusations levelled at the director spanning voyeurism, manipulation and exploitation. True to his anthropological roots (after training as a field biologist in Kenya and Alaska as a teen, he studied anthropology at Harvard), the Brooklynite’s special subject is usually the mind: he unrelentingly plunders the psyches of his main characters to probe the hellish limits of human behaviour.

Packing a visceral sucker punch, his latest, Caught Stealing, is a wild ride through the medley of subcultures and communities that make up 1990s New York. Adapted for the screen by Charlie Huston from his own novel, Austin Butler’s protagonist Hank makes the mistake of agreeing to cat-sit for his punk neighbour (Matt Smith) and winds up at the epicentre of a standoff between feuding drug lords. For a director known for dealing with mercilessly dark themes, it’s a swerve into lighter territory, although still hanging together by an existential thread.

As Caught Stealing lands in UK cinemas, here’s our guide for newcomers to Darren Aronofsky and his bold, histrionic body of work.

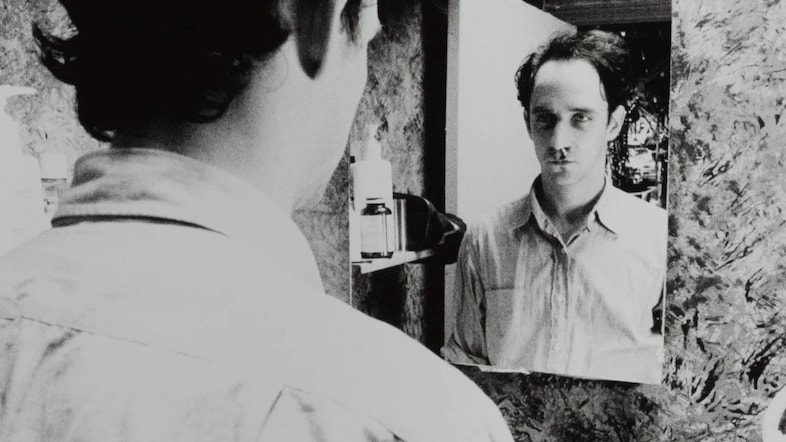

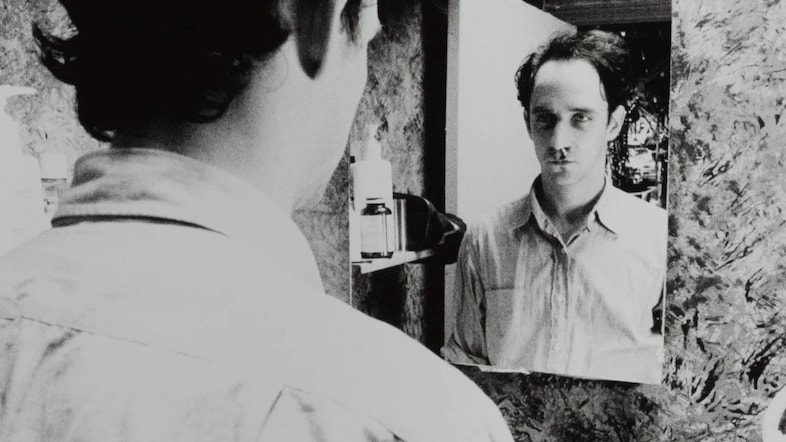

Aronofsky’s drum’n’bass-scored debut shattered thriller conventions and planted the thematic seeds which would flower in all his features to follow, from refrains of addiction to religion and mental breakdown. Paying tribute to his Jewish heritage, the film revolves around an antisocial, reclusive mathematician (Sean Gullette) living in Manhattan, who is trying to crack the stock market – but winds up feeding the Torah into his computer. A convulsive, high-octane black-and-white drama with notes of Akira Kurosawa and Satoshi Kon, this esoteric character study was miles ahead of The Da Vinci Code. Appropriately, it also became the first film downloadable on the internet.

A full-pelt, delirious and even nauseating riot of fast cuts, split screens, body-rigged cameras and time lapses, Aronofsky’s innovative attempt to represent the experience of drug use on screen was unsurprisingly contentious. Its double helix of a plot concerns a mother (Ellen Burstyn, Aronofsky managing to convince the acclaimed actress to come on board as an ailing widow) and son (Jared Leto), both contending with addiction in different forms. Adapted from Hubert Selby Jr’s 1978 novel of the same name, its hallucinatory sequences and subjective shots serve as much as a takedown of the flawed characters Aronofsky portrays as of the cruel systems they find themselves in.

For a filmmaker often defined by his dizzying ambition, Aronofsky’s mesmeric third film is undeniably his biggest leap of faith. Vaulting epically between time and space, the love shared by Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz’s characters ties them together across a trinity of interweaving existences: as a conquistador in the Mayan age, a traveller in the 26th century and a present-day surgeon seeking a cure for cancer. Facing several hurdles on its journey to completion – not least Brad Pitt, who was set to star, abandoning the production – the film was undeservedly maligned upon release. Inspired by the writings of Eduardo Galeano, this contemplation of the fragility of mortality is possibly Aronofsky’s most honest work.

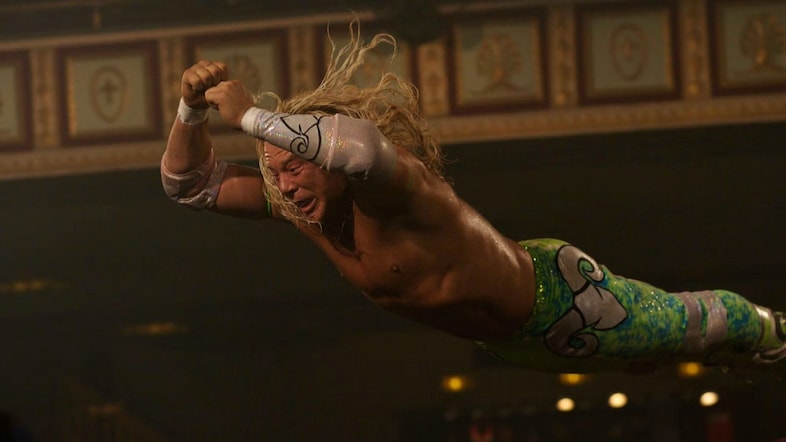

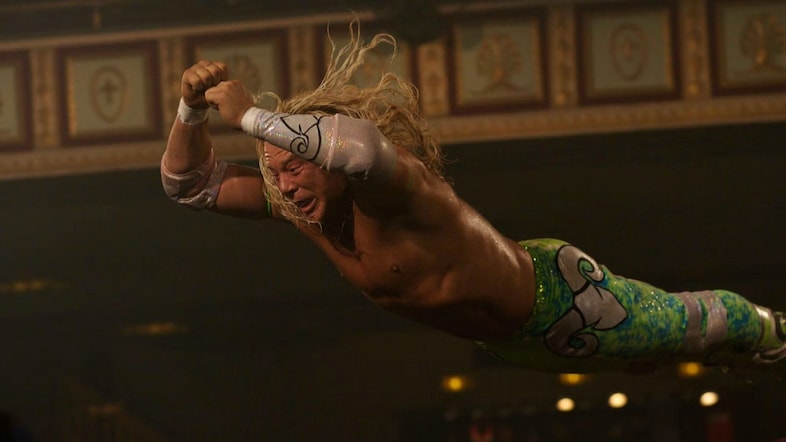

Aronofsky and lead actor Mickey Rourke’s fraught onset relationship brought a meta dimension to this long-gestating story of a washed-up wrestler under strain: the pair often came to blows, the director reportedly having to rally Rourke to get out of bed and prevent him from wearing sunglasses while filming. Their efforts paid off, with the former pro boxer giving an understated, effortlessly moving performance as The Ram. A shimmering, colourful companion piece to Black Swan, where the latter is about the chains of femininity and gendered oppression, the former explores the strictures of toxic masculinity. But beneath the entrancing spectacle, both share an unstoppable death drive pushing them toward their tragic ends.

Aronofsky’s later work gained a double edge – most obvious here, where the pastel pinks of a New York City Ballet dancer’s kitsch, claustrophobic childhood bedroom (where she continues to sleep as an adult) and present-day wardrobe are pitted against the gothic blacks of her sinister alter ego. Natalie Portman gives a career-topping performance as Nina Sayers, the actor training to dance most of the giddying sequences that made the final cut. When an enigmatic new dancer (Mila Kunis) joins the company, threatening to take Nina’s long-awaited role, tensions are stoked and Nina descends into a whirlpool of repressed desire and self-loathing.

Opening – a little heavy-handedly – with Jennifer Lawrence uttering the word “baby?”, Aronofsky’s follow-up to Noah built on its biblical themes. Part ecological parable, part indictment of the artist as a self-centred man, the film sees a sheeny, goddess-like Lawrence have her perfectly preserved country haven transformed into a funeral parlour, a cult shrine and eventually a full-blown war zone – a show home for the worst of humanity. Infamously (and unfairly), the film gained a notorious F rating from CinemaScore and was branded the “worst film of the century”. Real-life brothers Domhnall and Brian Gleeson make a cameo as Cain and Abel.

Caught Stealing is out in UK cinemas now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

As Caught Stealing arrives in UK cinemas, we examine one of contemporary Hollywood’s most disturbing and divisive oeuvres

If there is a rule to Darren Aronofsky’s work, it is that any given film from his nine feature-strong oeuvre will be a gruelling watch. Never going easy on the grossness, toe-stubbing, head-drilling, anguish and misery – whether a sweeping Biblical epic (Noah) or a tightly wound ballerina tragedy (Black Swan) – Aronofsky has cemented his status as one of contemporary cinema’s most divisive directors. Part of the reason behind his stylistic audacity could be sheer confidence or fear-dissolving ambition: the now 56-year-old director founded his own production company straight after making his student graduation film, aged 28.

First crashing on to the film festival circuit in 1998 as his head-turning debut Pi premiered at Sundance, Aronofsky has been an explosive presence ever since. His work is often met with torrid debate (as well as, occasionally, censorship or bans), the accusations levelled at the director spanning voyeurism, manipulation and exploitation. True to his anthropological roots (after training as a field biologist in Kenya and Alaska as a teen, he studied anthropology at Harvard), the Brooklynite’s special subject is usually the mind: he unrelentingly plunders the psyches of his main characters to probe the hellish limits of human behaviour.

Packing a visceral sucker punch, his latest, Caught Stealing, is a wild ride through the medley of subcultures and communities that make up 1990s New York. Adapted for the screen by Charlie Huston from his own novel, Austin Butler’s protagonist Hank makes the mistake of agreeing to cat-sit for his punk neighbour (Matt Smith) and winds up at the epicentre of a standoff between feuding drug lords. For a director known for dealing with mercilessly dark themes, it’s a swerve into lighter territory, although still hanging together by an existential thread.

As Caught Stealing lands in UK cinemas, here’s our guide for newcomers to Darren Aronofsky and his bold, histrionic body of work.

Aronofsky’s drum’n’bass-scored debut shattered thriller conventions and planted the thematic seeds which would flower in all his features to follow, from refrains of addiction to religion and mental breakdown. Paying tribute to his Jewish heritage, the film revolves around an antisocial, reclusive mathematician (Sean Gullette) living in Manhattan, who is trying to crack the stock market – but winds up feeding the Torah into his computer. A convulsive, high-octane black-and-white drama with notes of Akira Kurosawa and Satoshi Kon, this esoteric character study was miles ahead of The Da Vinci Code. Appropriately, it also became the first film downloadable on the internet.

A full-pelt, delirious and even nauseating riot of fast cuts, split screens, body-rigged cameras and time lapses, Aronofsky’s innovative attempt to represent the experience of drug use on screen was unsurprisingly contentious. Its double helix of a plot concerns a mother (Ellen Burstyn, Aronofsky managing to convince the acclaimed actress to come on board as an ailing widow) and son (Jared Leto), both contending with addiction in different forms. Adapted from Hubert Selby Jr’s 1978 novel of the same name, its hallucinatory sequences and subjective shots serve as much as a takedown of the flawed characters Aronofsky portrays as of the cruel systems they find themselves in.

For a filmmaker often defined by his dizzying ambition, Aronofsky’s mesmeric third film is undeniably his biggest leap of faith. Vaulting epically between time and space, the love shared by Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz’s characters ties them together across a trinity of interweaving existences: as a conquistador in the Mayan age, a traveller in the 26th century and a present-day surgeon seeking a cure for cancer. Facing several hurdles on its journey to completion – not least Brad Pitt, who was set to star, abandoning the production – the film was undeservedly maligned upon release. Inspired by the writings of Eduardo Galeano, this contemplation of the fragility of mortality is possibly Aronofsky’s most honest work.

Aronofsky and lead actor Mickey Rourke’s fraught onset relationship brought a meta dimension to this long-gestating story of a washed-up wrestler under strain: the pair often came to blows, the director reportedly having to rally Rourke to get out of bed and prevent him from wearing sunglasses while filming. Their efforts paid off, with the former pro boxer giving an understated, effortlessly moving performance as The Ram. A shimmering, colourful companion piece to Black Swan, where the latter is about the chains of femininity and gendered oppression, the former explores the strictures of toxic masculinity. But beneath the entrancing spectacle, both share an unstoppable death drive pushing them toward their tragic ends.

Aronofsky’s later work gained a double edge – most obvious here, where the pastel pinks of a New York City Ballet dancer’s kitsch, claustrophobic childhood bedroom (where she continues to sleep as an adult) and present-day wardrobe are pitted against the gothic blacks of her sinister alter ego. Natalie Portman gives a career-topping performance as Nina Sayers, the actor training to dance most of the giddying sequences that made the final cut. When an enigmatic new dancer (Mila Kunis) joins the company, threatening to take Nina’s long-awaited role, tensions are stoked and Nina descends into a whirlpool of repressed desire and self-loathing.

Opening – a little heavy-handedly – with Jennifer Lawrence uttering the word “baby?”, Aronofsky’s follow-up to Noah built on its biblical themes. Part ecological parable, part indictment of the artist as a self-centred man, the film sees a sheeny, goddess-like Lawrence have her perfectly preserved country haven transformed into a funeral parlour, a cult shrine and eventually a full-blown war zone – a show home for the worst of humanity. Infamously (and unfairly), the film gained a notorious F rating from CinemaScore and was branded the “worst film of the century”. Real-life brothers Domhnall and Brian Gleeson make a cameo as Cain and Abel.

Caught Stealing is out in UK cinemas now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.