Rewrite

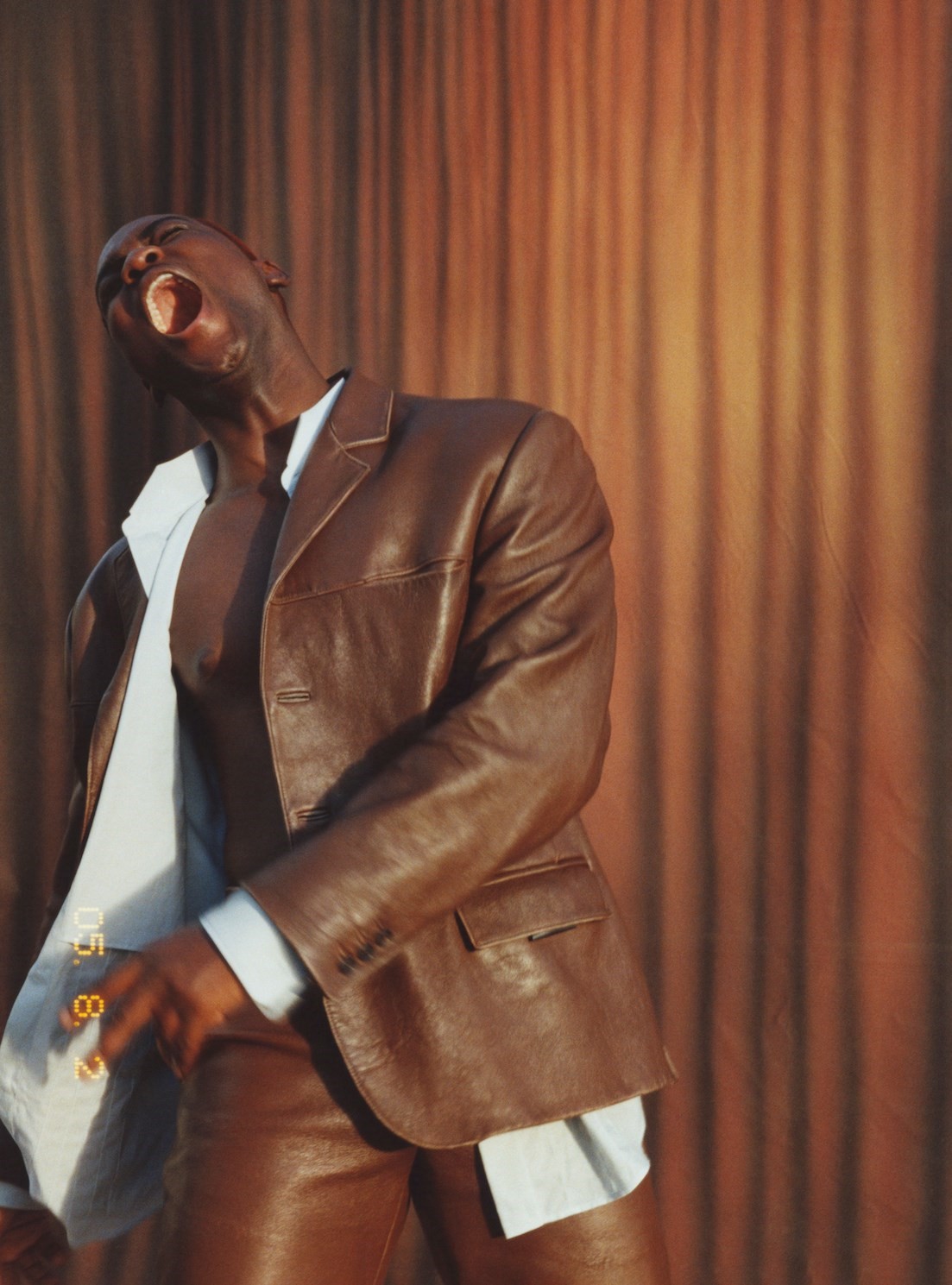

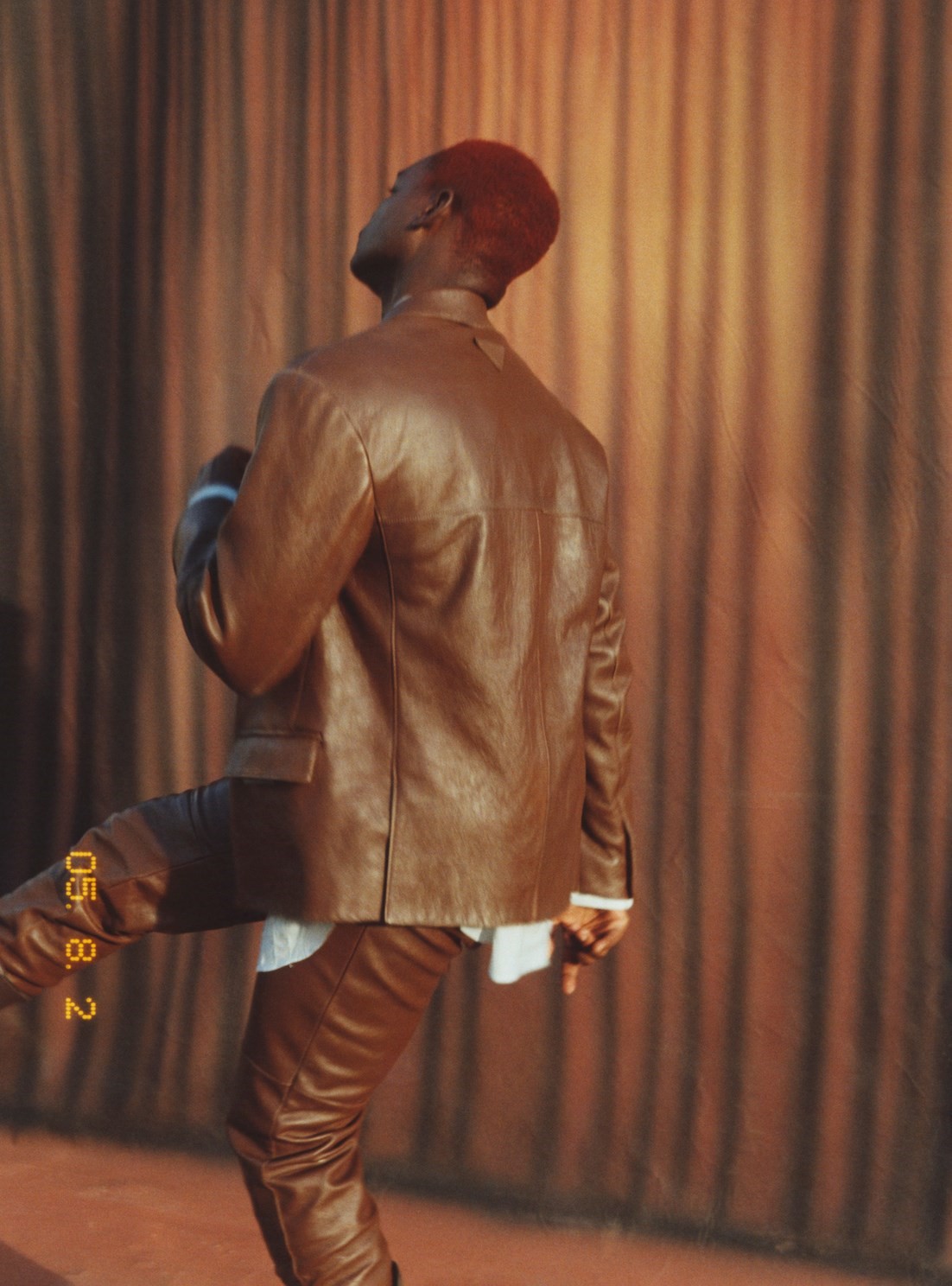

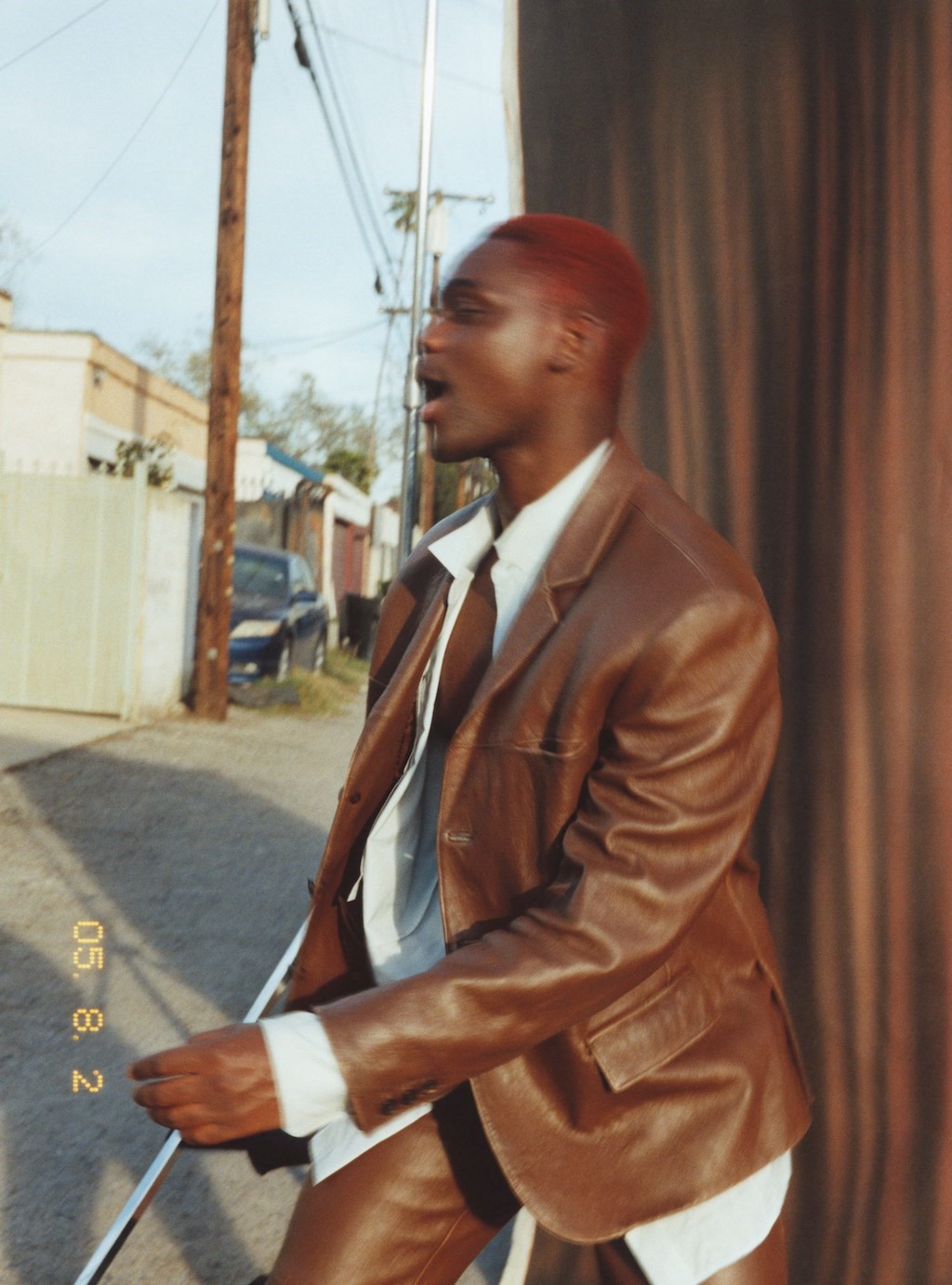

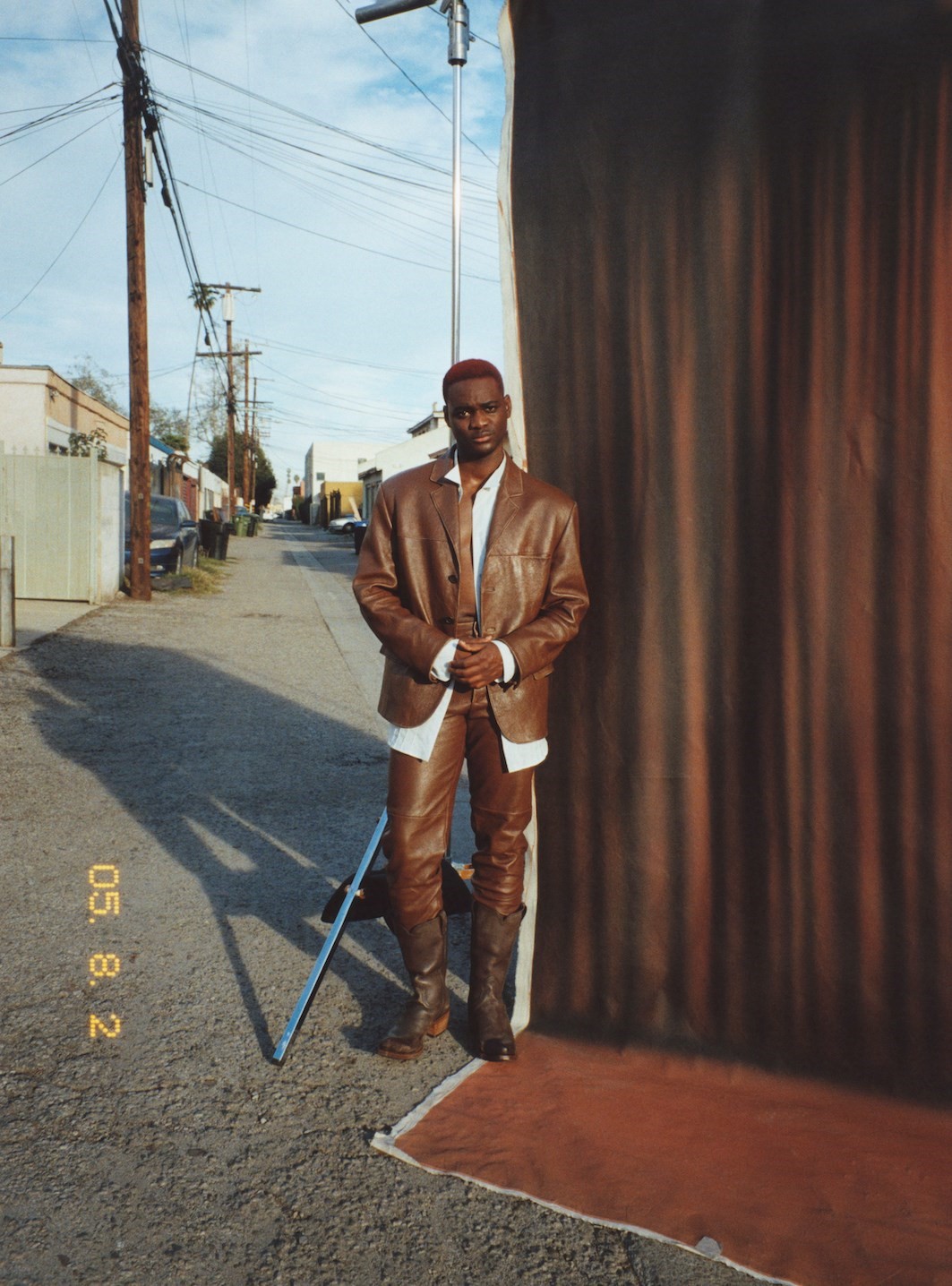

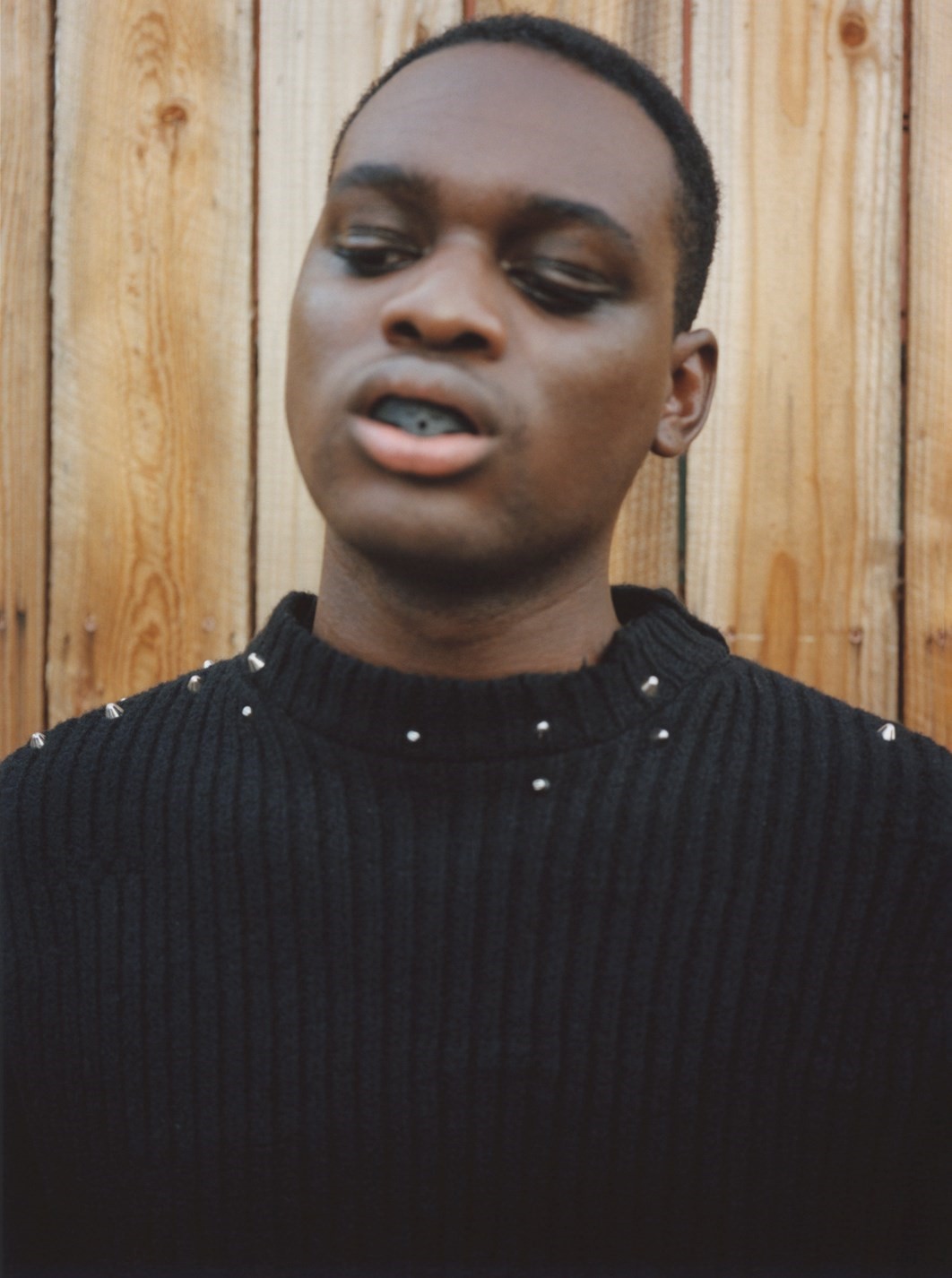

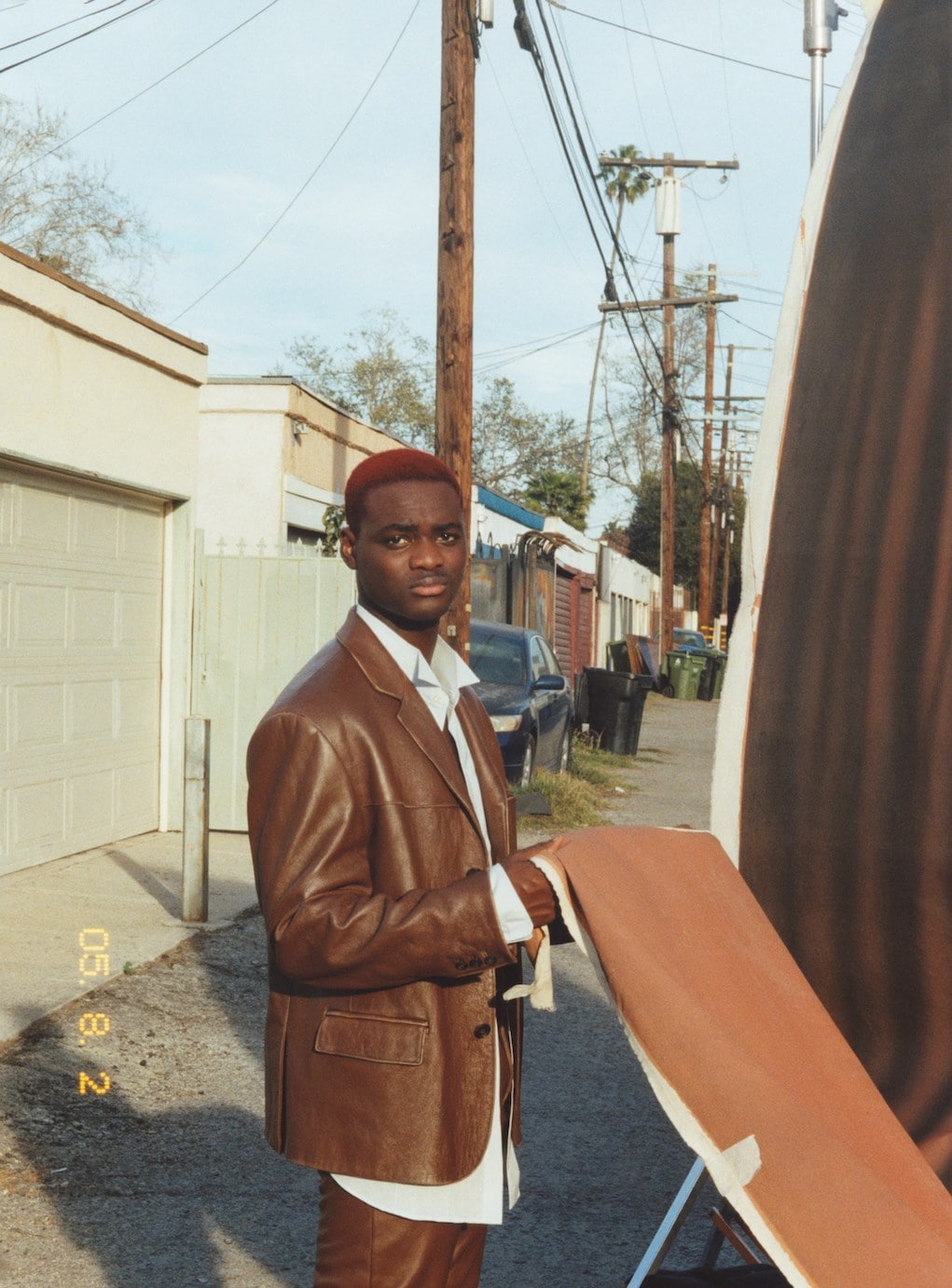

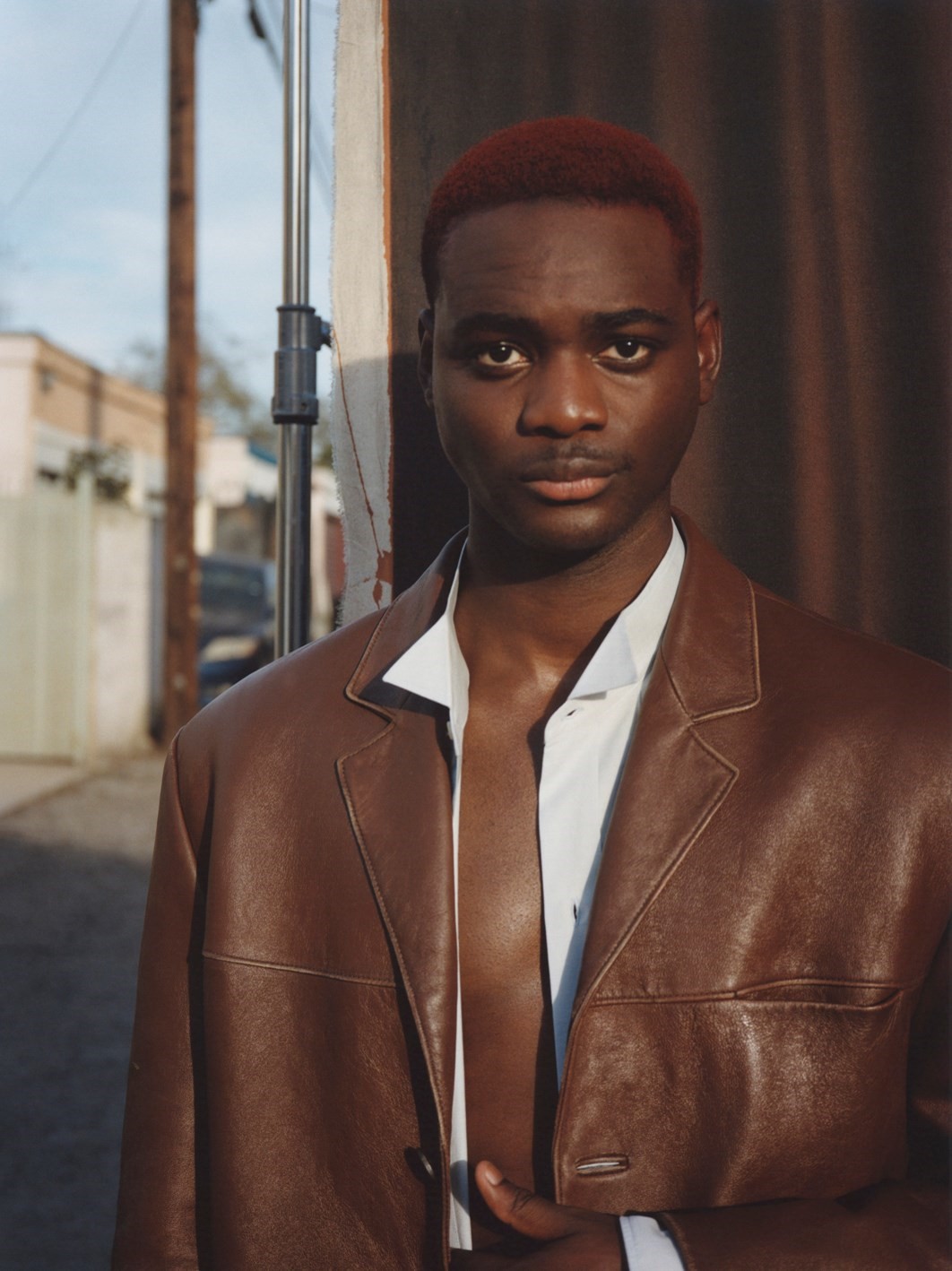

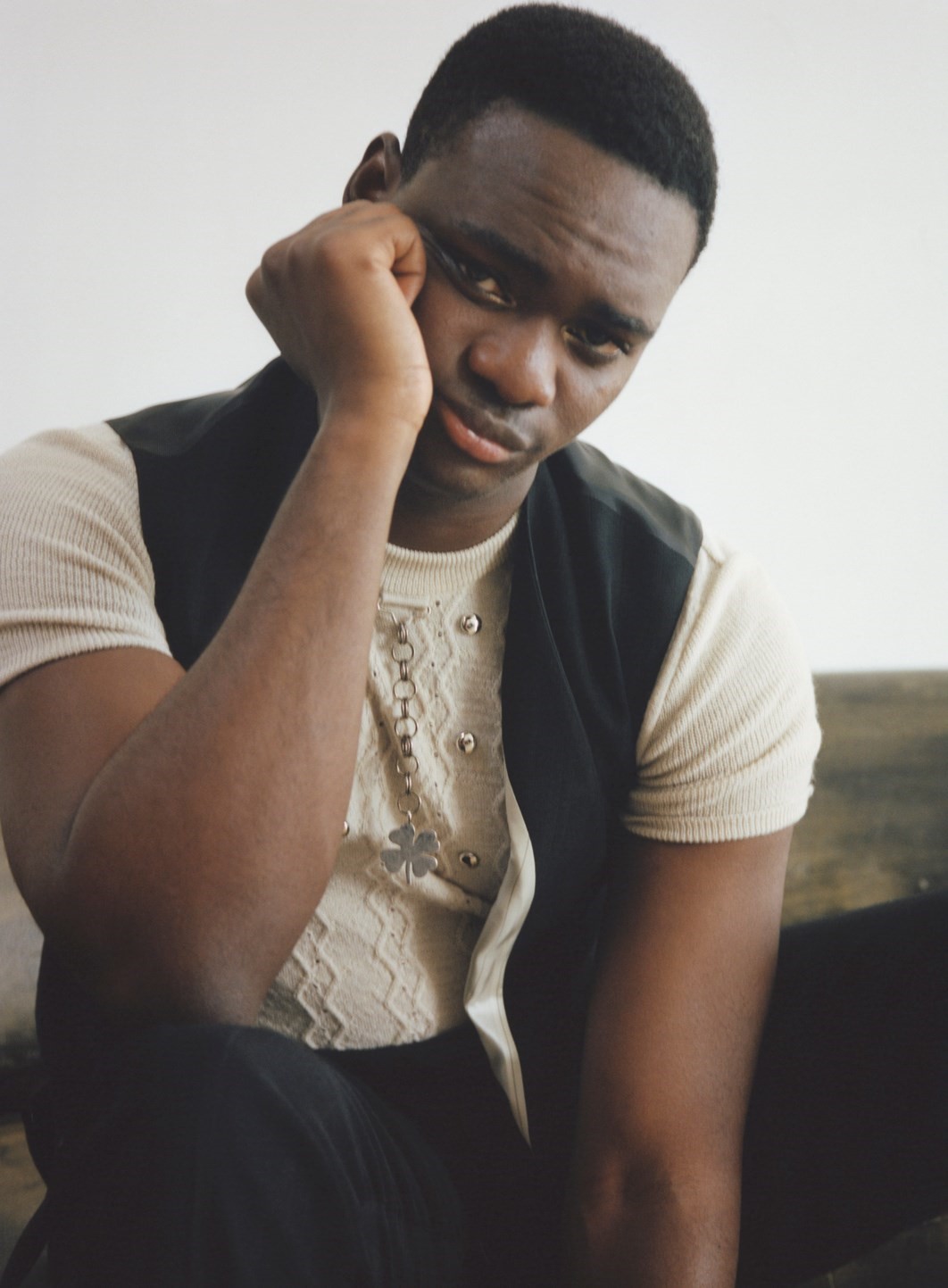

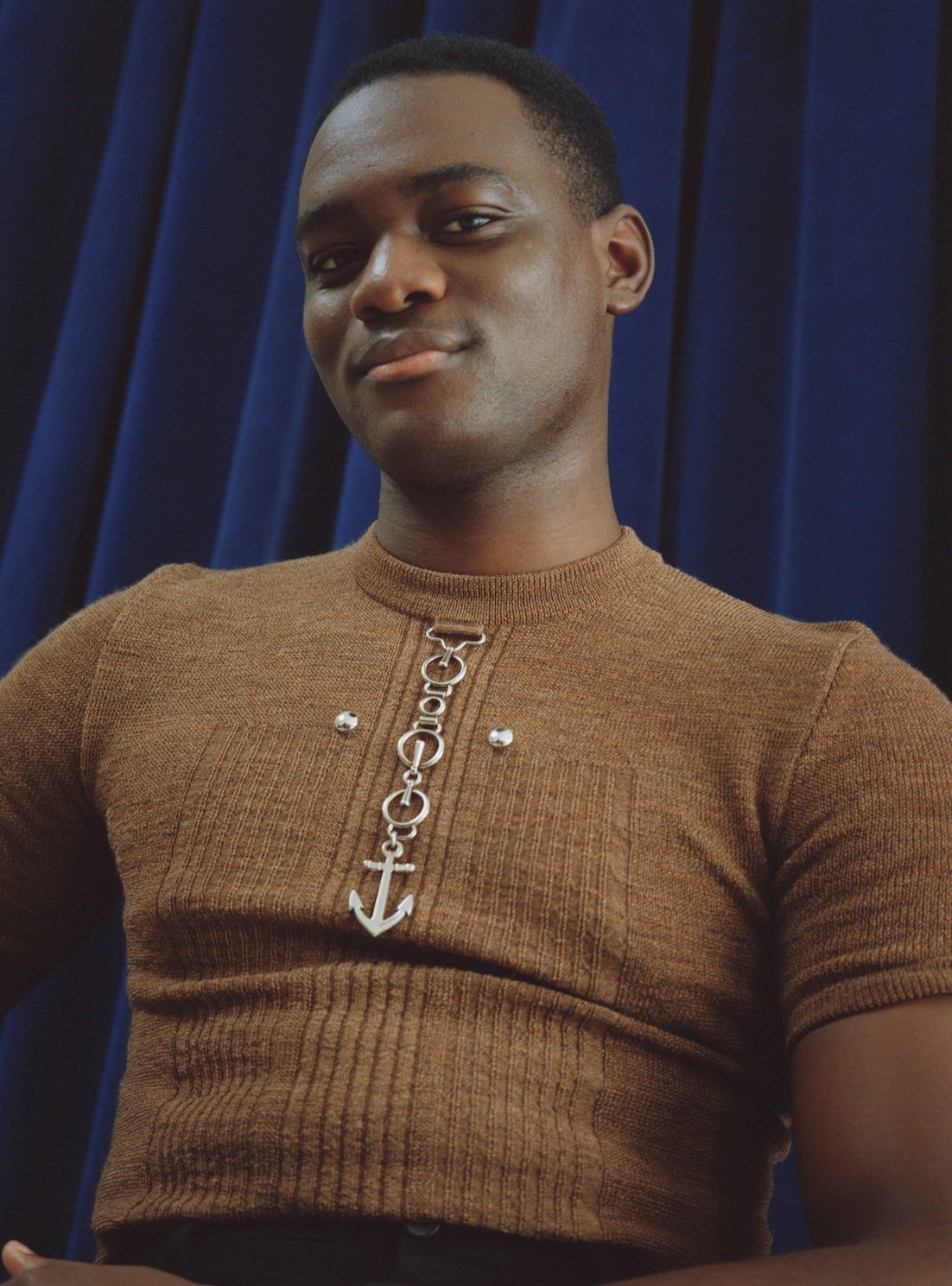

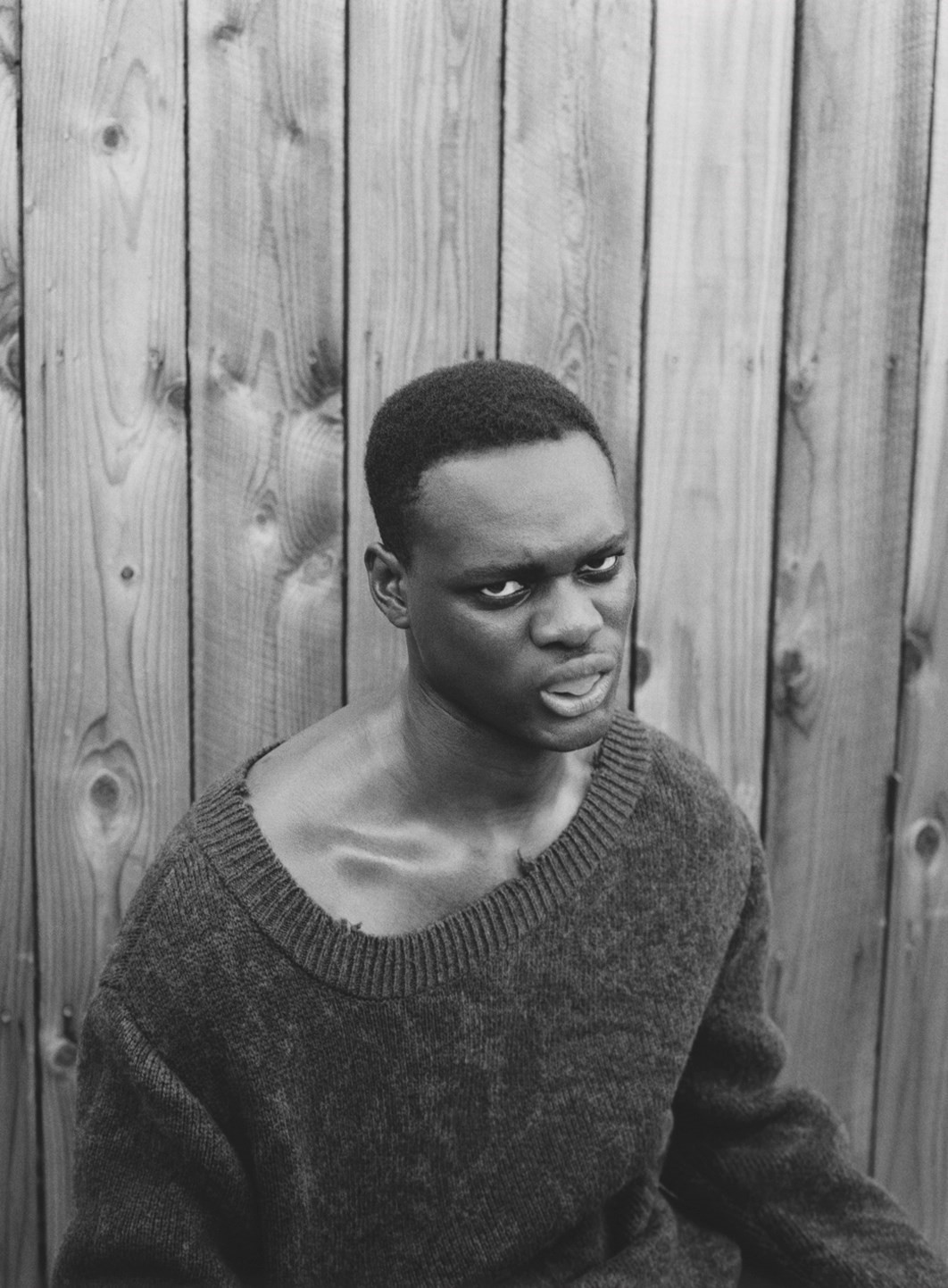

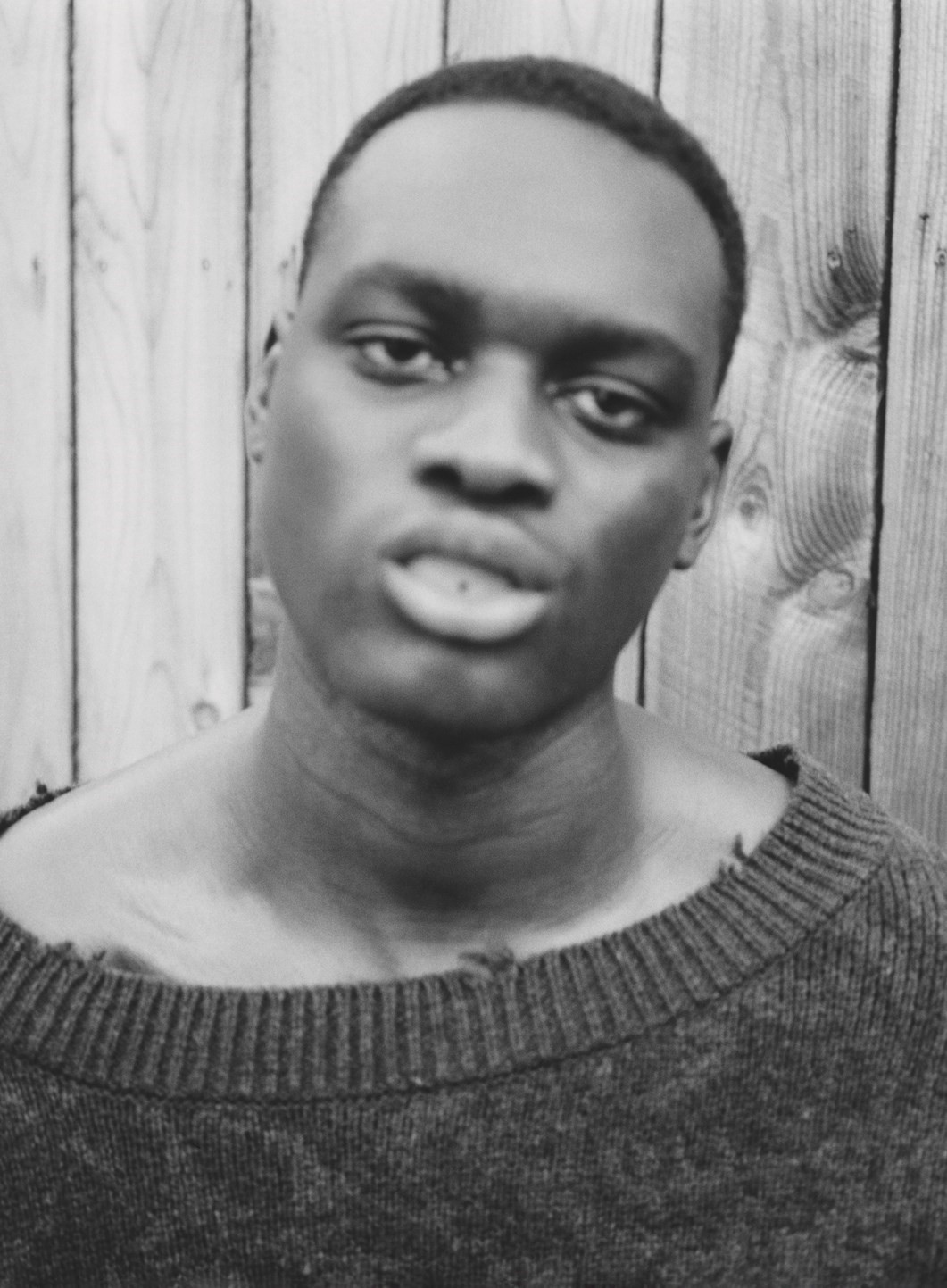

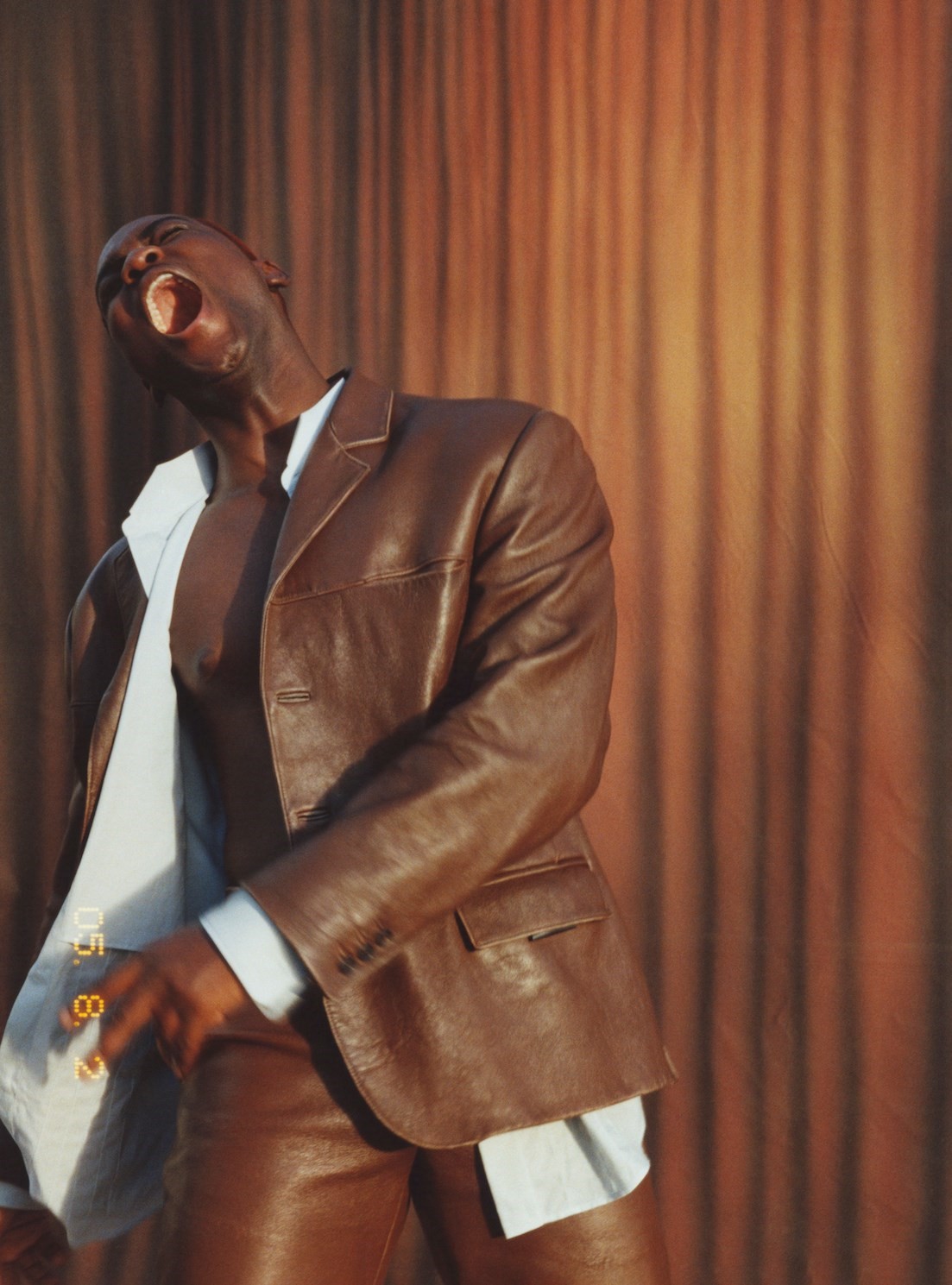

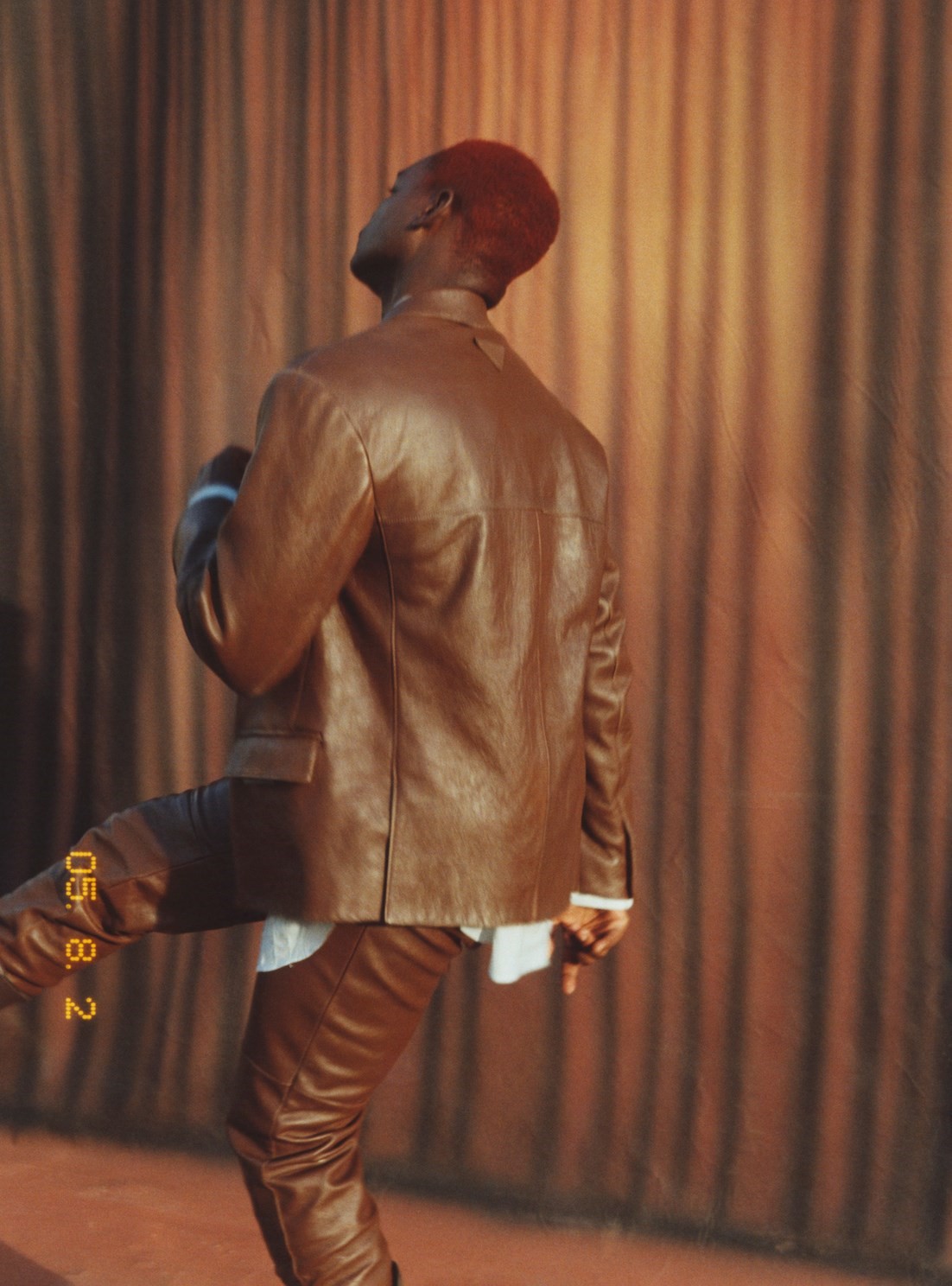

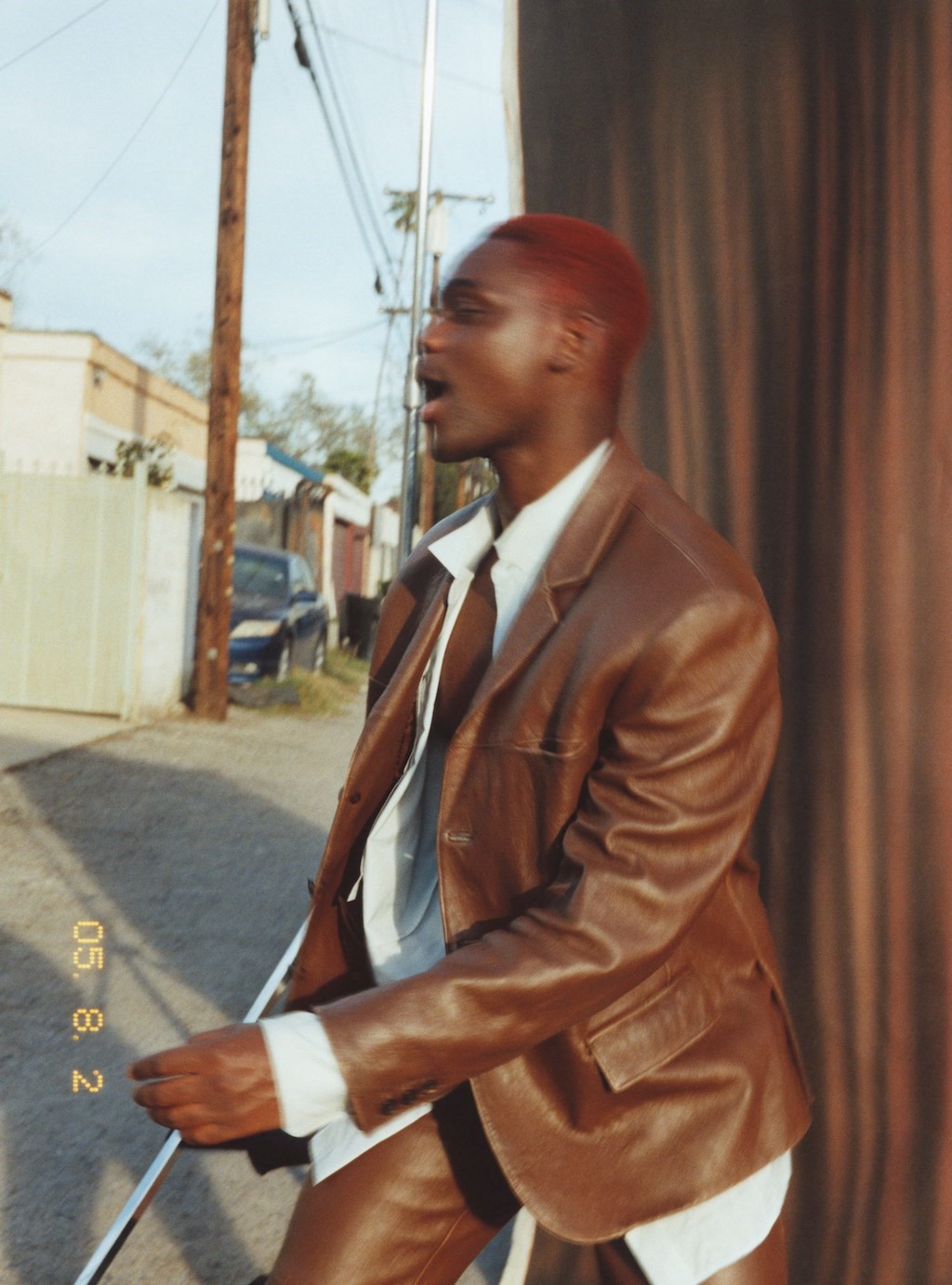

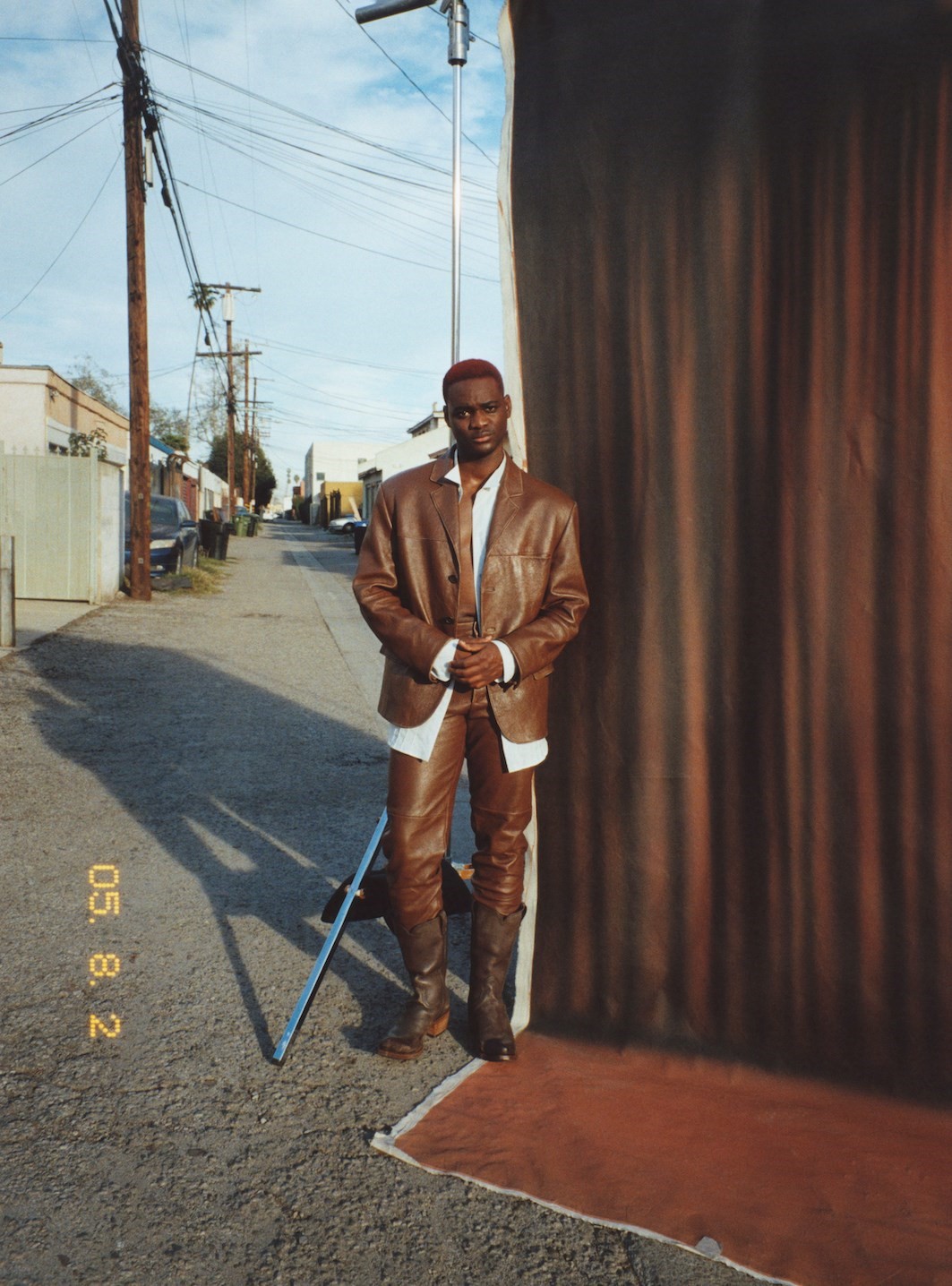

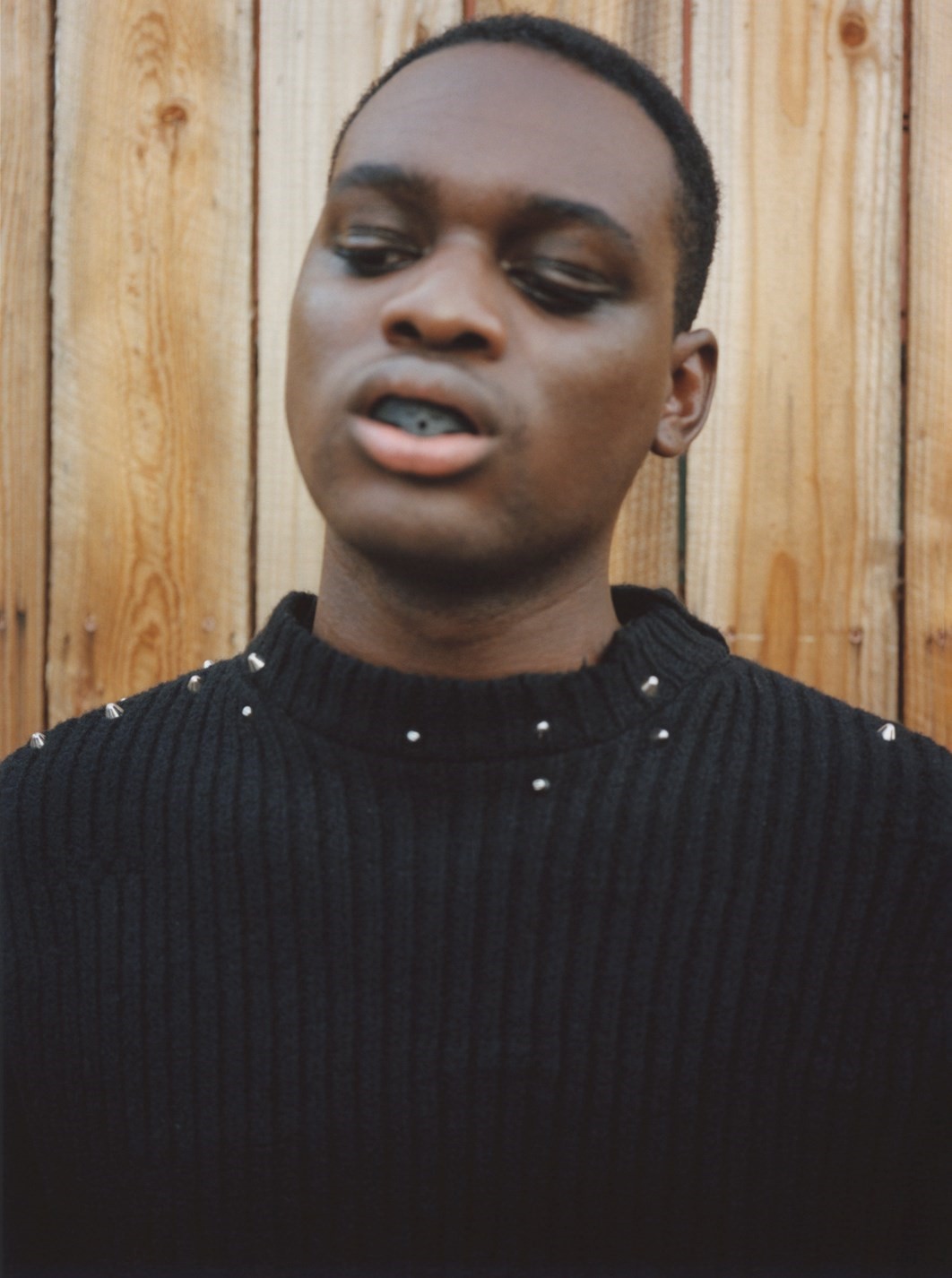

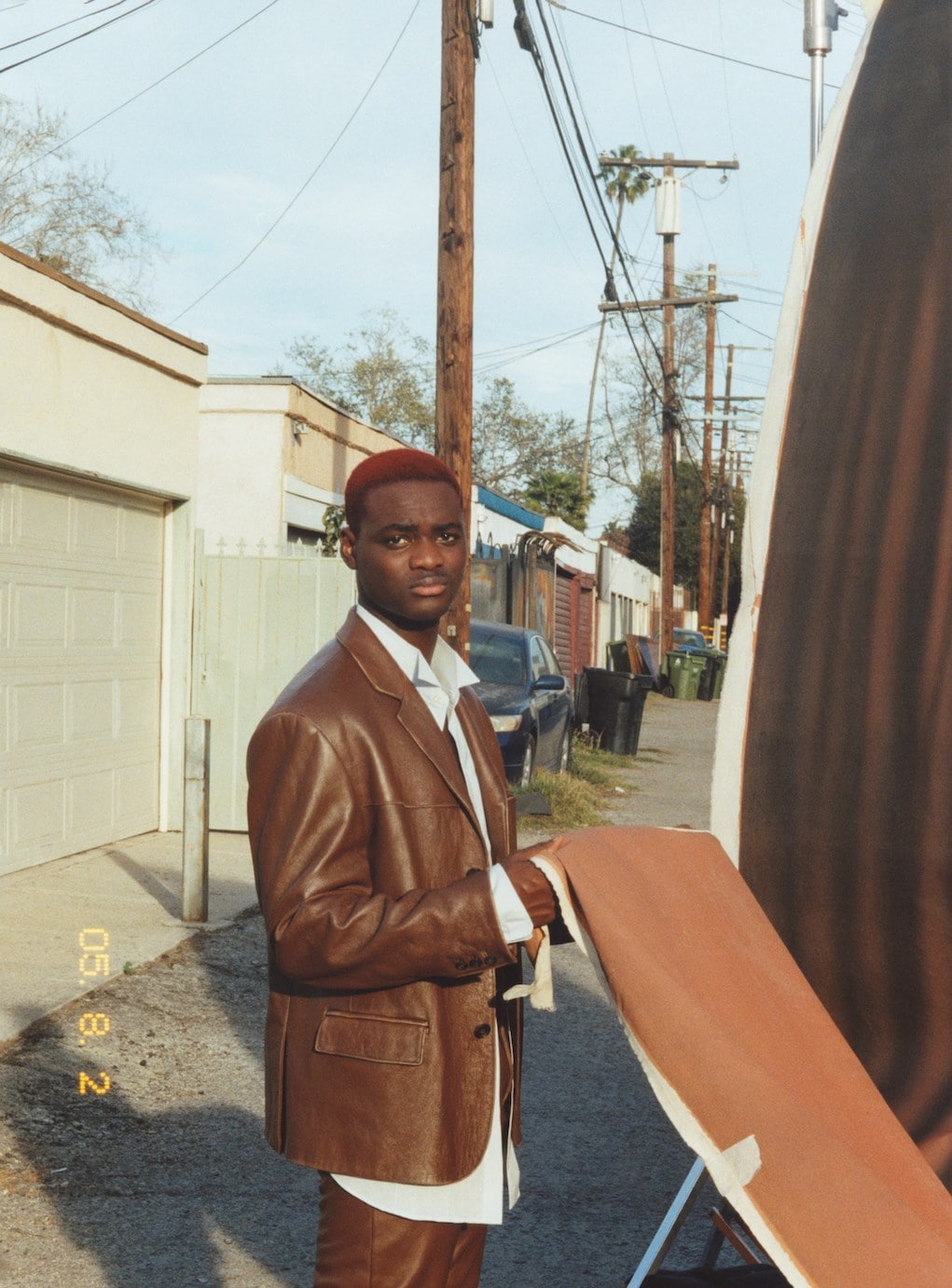

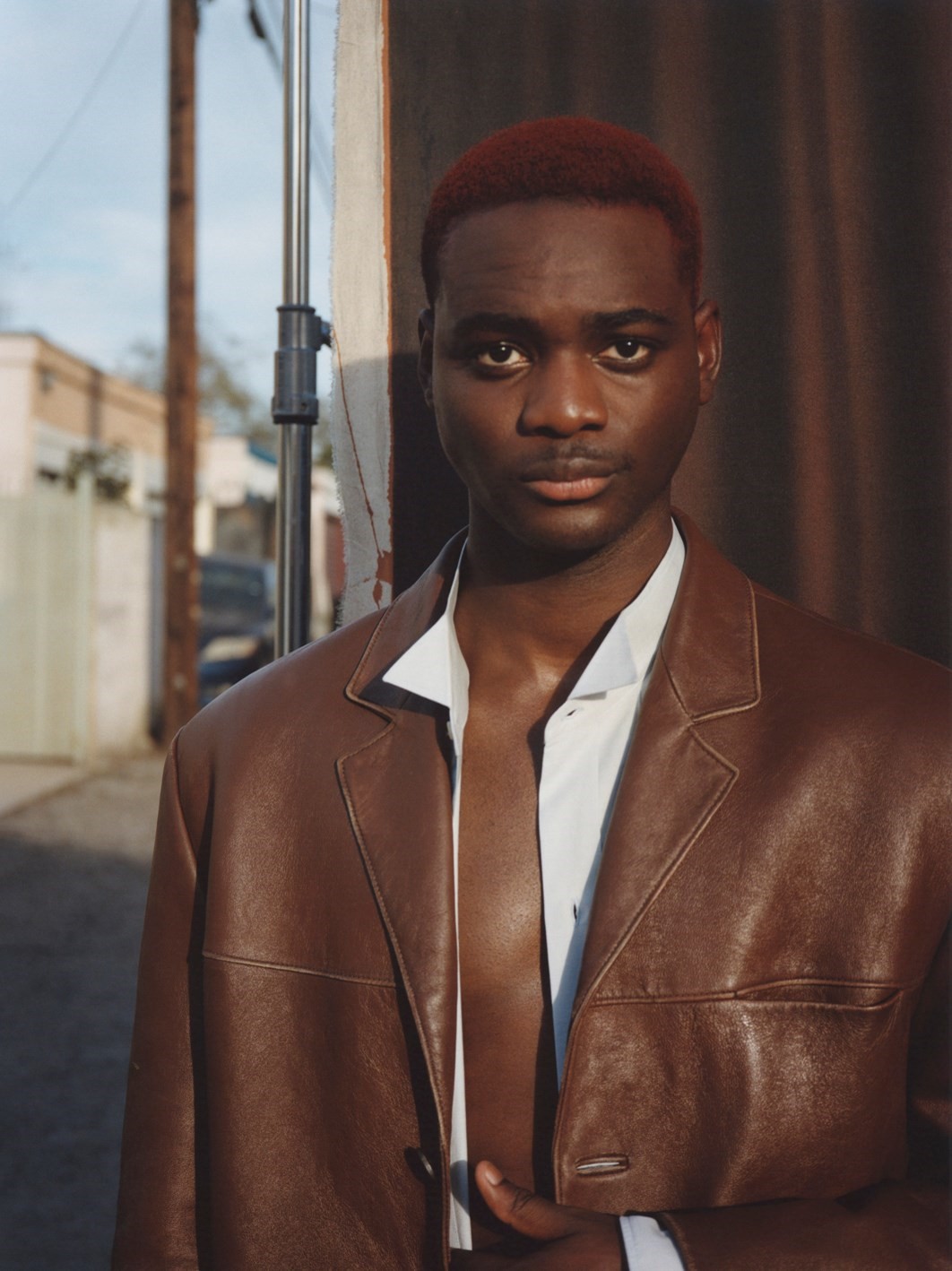

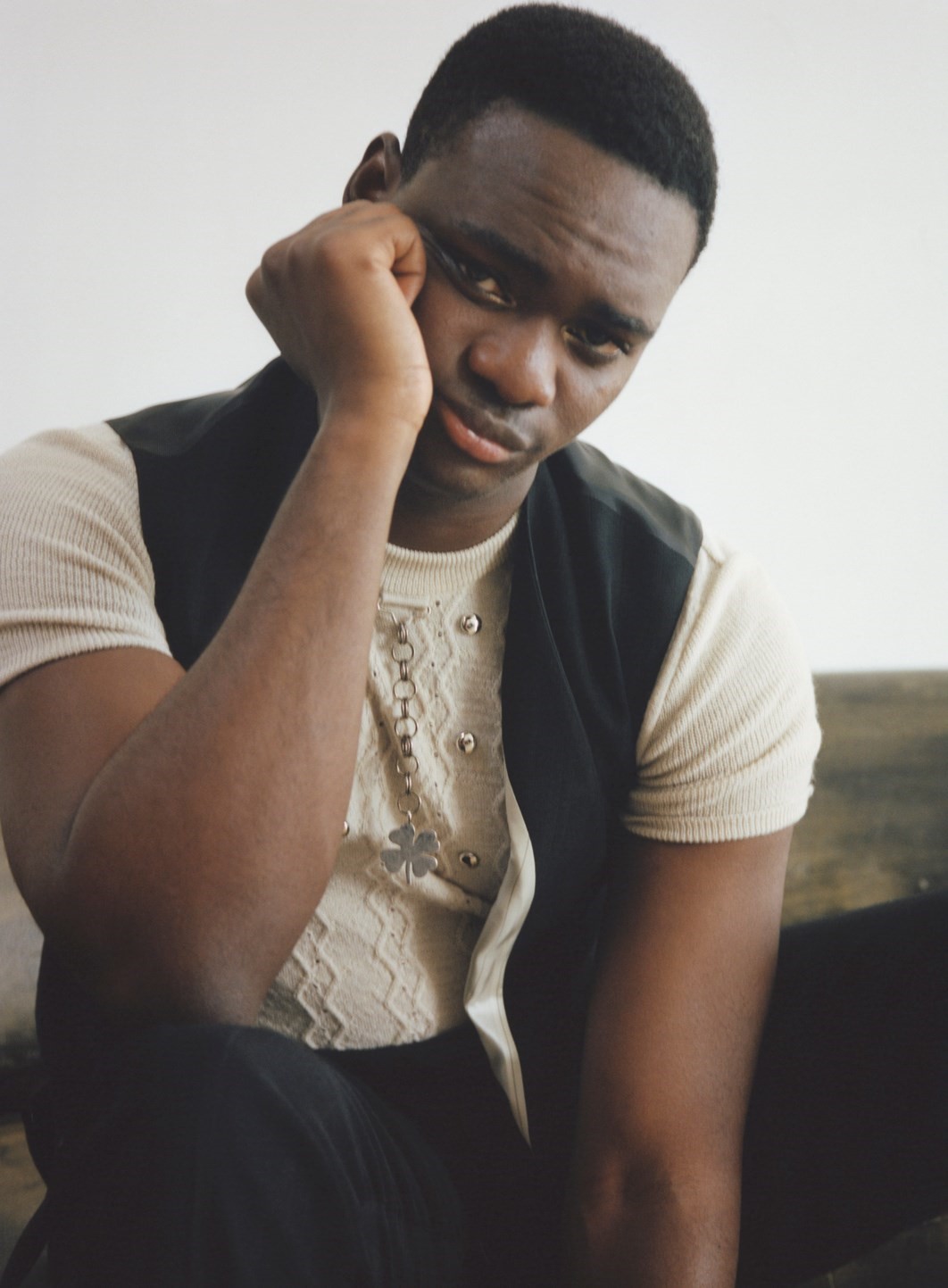

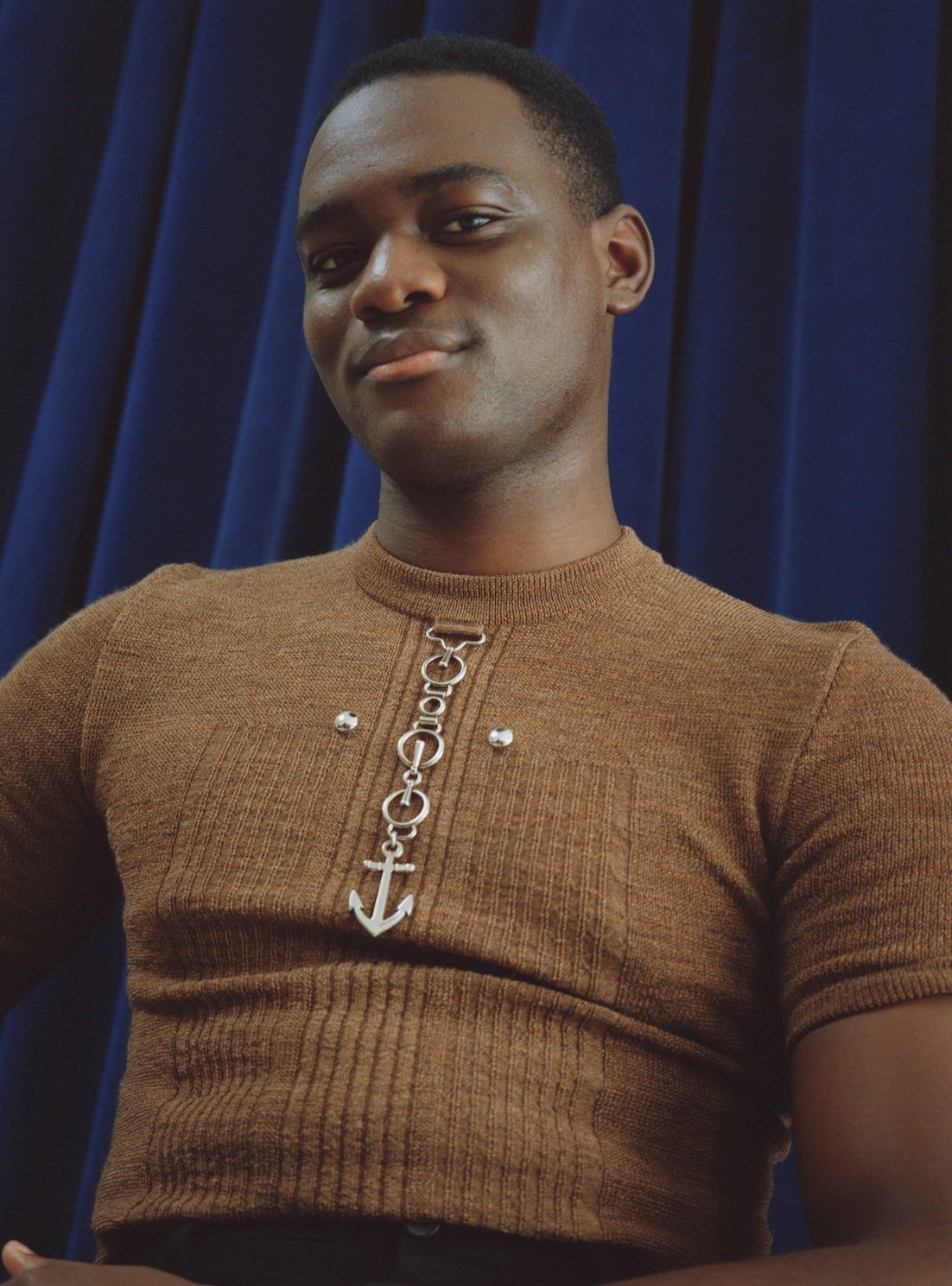

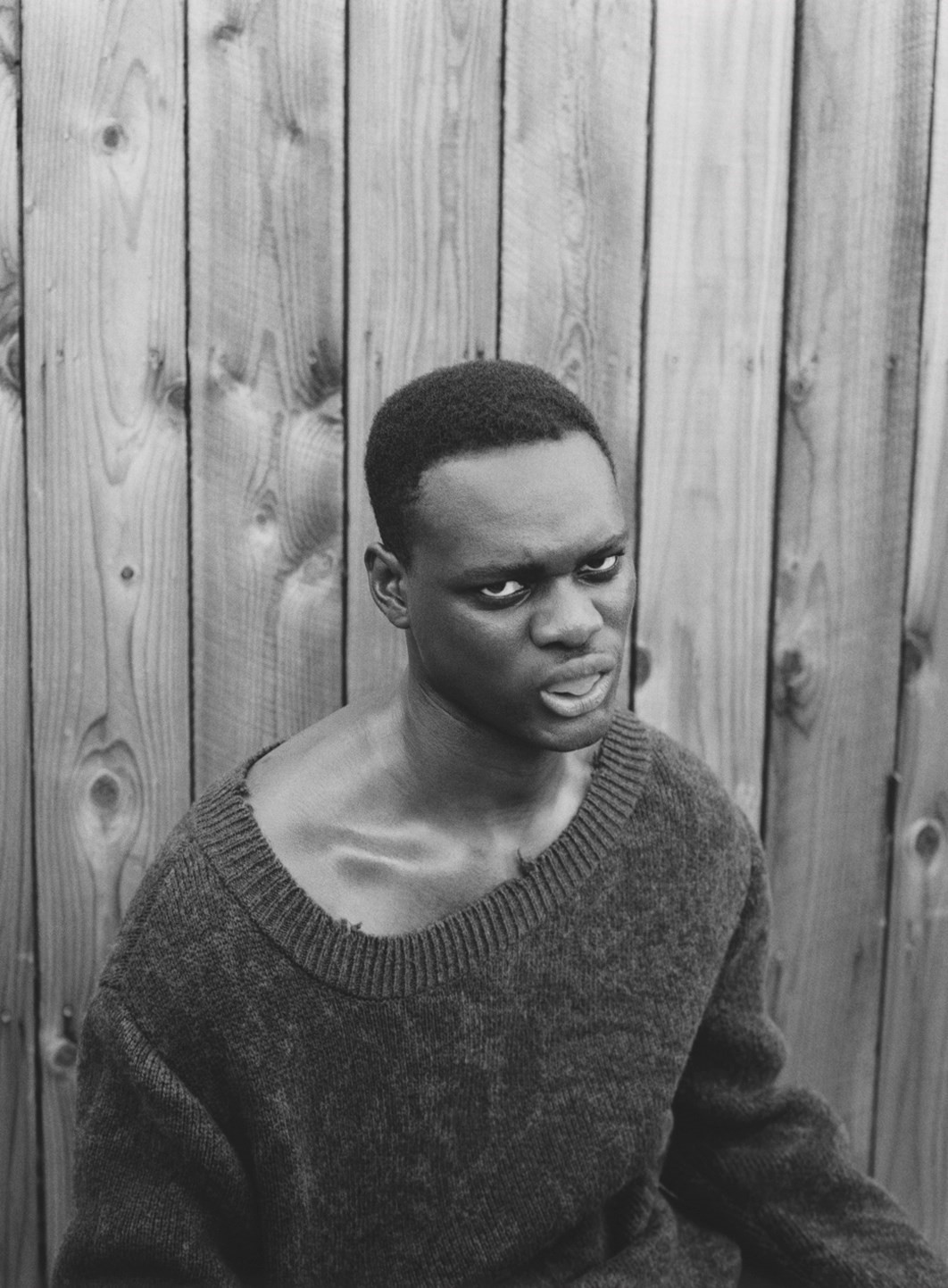

Lead ImageEthan Herisse wears Prada AW25Photography by Martine Syms, Styling by Julie Ragolia

This story is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from April 24.

Ethan Herisse was not expecting a callback. The chemistry read, he thought, had gone well enough by most metrics. They gelled. It felt good. But when it was over, the director for Nickel Boys, RaMell Ross, who had beamed into the audition room via Zoom, said to Brandon Wilson, “OK, Brandon – I’ll talk to you later,” and to Herisse he said, “Goodbye.”

“I was just like, ‘Damn, right in front of me like that is craaazy,’” jokes the 24-year-old, glancing around his bedroom in mock exasperation. The room is dark, lit only by a bedside lamp behind him and the glow of the computer screen reflected in his silver glasses, but I can make out a couple of items: movie posters above the bed, a street sign that reads “DO NOT ENTER: WRONG WAY”, another, beneath it, that says “BENVENUE ST”. He’s dressed in a greyish-blue zip-up chambray shirt – which he occasionally uses to clean his lenses – silver hoops in his ears, and a thin, silver chain around his right wrist.

Wilson, he says, who had already done a read with a different actor by the time he met Herisse, was sure this one was it, that some covalent bond had spontaneously formed between them in that room and they would be making the movie together, but Herisse wasn’t so sure. “Brandon’s a lot more confident than me about that sort of thing,” he says. For a young actor at the beginning of his career, much of the invisible administrative work involves inoculating the ego against rejection, bracing constantly for bad news like a traumatised survivalist. The breakout, ever dreamed about, is always deferred.

And he’d been excited about the script, this balletic meditation on trauma, memory, the machinery of American racism, the nuances of Black male friendship, and the boundaries between the self and the Other. “I had already read The Underground Railroad, and really liked it,” says Herisse, who is naturally interested in the embarrassing, under-examined aspects of American history — stories, jettisoned into the the dark corners of the public imagination, that reveal to him his own ignorance, his own belated encounters with slavery’s many afterlives. Ross’s film, set in 1960s Florida and adapted from the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Colson Whitehead, follows the tragedy of Elwood Curtis, a brilliant, idealistic young student whose life is upended when he’s interned at an abusive “reform school” for hitching a ride, accidentally, in a stolen Pontiac. At Nickel Academy – based on the real-life Dozier School for Boys, where Black boys as young as eight could be held for “charges” as innocuous as truancy and where, in 2019, dozens of graves were discovered – Elwood is befriended by Turner (Wilson), a cynical, charismatic boy around his age who defends him and shows him the ropes, including literal, frayed ones used for lynchings in the forest. At Nickel Academy, the boys attempt to keep each other alive.

A couple of days after the audition, Herisse’s phone buzzed. He was in class at UC Irvine. It’s difficult to speak to your manager about the results of a chemistry read when you’re being bombarded with a lesson on actual, molecular chemistry – particularly when it’s an arduous course exploring the synthesis and behaviours of inorganic compounds, whatever that means – and so Herisse, who was in the home stretch of his degree, declined the call like a good, responsible student. “We were only a few weeks in, and I was already getting my ass beat,” he admits. (Studying chemistry, not acting, is the hardest thing he’s ever done.) But his manager insisted it was an emergency, and when he excused himself to ring her back, she patched his agent and his parents onto the call. “I walked back into that classroom, and I didn’t take a single other note,” says Herisse. “I sat down, turned to my friend, and was like, ‘I’m not coming back for the rest of the quarter. See you later!’” Obviously, he got the part. It was the best drive home of his life.

Ethan Herisse is not new to the camera though. He’s been acting in some form or another since he was 11 years old, when he chaperoned his younger sister to her acting classes and then decided he wanted to perform, too. There were other gigs before this one, small TV parts in The Mindy Project and Key & Peele and Chicago Med, and back in 2019, he had to take a furlough from his studies to film Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us, a harrowing miniseries based on the infamous case of the Central Park Five. But Nickel Boys promised to be different, his first lead role on the big screen.

And it’s an ambitious gambit. Probably, most actors do not expect their breakthrough roles to be for films in which they hardly ever appear directly. (“I like the movie,” a friend sheepishly told him after seeing it. “I just wish I saw your face more.”) But Ross, a six-foot-six former basketball player and current professor of visual art at Brown University, wanted to adapt the story through an impressionistic, experimental prism, and has rendered it in a collage-like accretion of sensual, first-person images. “Make the camera an organ,” he wrote in Renew the Encounter, a 2019 manifesto on photography and the white gaze. “Take it into your body. Shoot toward a personal poetics.”

What we witness, then, is a big bang of subjectivity, the extraordinary birth of a consciousness and the requisite storm of darkening images that breach the Black child’s innocence: glittering, falling ribbons of Christmas tinsel, a boozy house party witnessed at table level, the open face of a sermonising Martin Luther King in a stack of storefront televisions – each memory is swept away, gradually and then all at once, by hand-drawn lynching cartoons scrawled in a textbook, the hard partition in the back of a police car, an orange grove refashioned into a contemporary plantation. We don’t actually see Elwood until 36 minutes of the film have elapsed, and when we finally do, in a breathtaking body-jump that replays, from Turner’s perspective, a scene we have just witnessed, Herisse conveys to us the exact shape of Elwood’s deflation: his posture is resigned, his eye contact furtive, his voice slightly trembling. He cried when he first watched it back with his parents, hardly recognised himself until the credits rolled. His dad was speechless. “You need to do a comedy next,” his mother told him. (When They See Us is not exactly Sunday morning viewing, either.) She has gone back to watch it again three other times. His dad went back twice.

The net effect of the film is devastating, but the experience of shooting it was not. Ross, he says, has a curious, relaxed way of working. He would sometimes see Herisse meandering around, playing with a spider web or wrapping a string around his finger, and then he would put it in the film. In this way, the film becomes, at times, a reflection of its lead actor’s own sensitivities, his own particular gaze. He got really close with his co-star, Wilson, and that intimacy somehow suffuses the movie, though they appear together in just one single, breathtaking frame over the course of the whole two hours. The crew shot Nickel Boys in New Orleans, and the week they were supposed to begin, Ross got Covid. “For the week that production was shut down, B and I were just, like, roaming the city,” says Herisse. They went to the movies and saw Tár (Wilson’s favourite), Bones & All (Herisse’s favourite), and The Banshees of Inisherin (neither of their favourites, but they liked it). They went to Bourbon and Frenchmen Streets, had their senses overwhelmed by drunken chaos and the swell of jazz music.

“My manager made a joke the other day where she was like, ‘If someone asks about you for a project, I have to ask, ‘Well, is it heavy? Will something awful happen to him?’ If the answer is yes, then I know you’ll probably do it’” – Ethan Herisse

And they went to Waffle House. “Bro, Brandon does not play about Waffle House,” he says. It was Wilson who introduced Herisse to Waffle House, and eventually, the pair established Waffle House Mondays: whenever they would wrap shooting on a Monday, they’d find the nearest one and invite everyone. (Herisse would get the All Star Special. Ross would get six eggs and grits. In college, they called him Six Eggs. Eventually, he brought it down to five.)

The boys of Nickel Boys represent a political philosophy divided, a bond that turns out to be ionic. Elwood, a disciple of King, is righteous and a little bit romantic, a near- unwavering believer in one man’s capacity to change a world intent to destroy him; Turner, who has been at Nickel for longer, whose alcoholic mother abandoned him, is more of a defeatist, having witnessed so much degradation and found no salve or solution. “When I was reading the script, I was seeing Elwood as I saw myself at 16,” says Herisse.

“I’ve always been an optimistic person. I think I have this wide-eyed, naïve outlook on the world, and I’ve always been protected from a lot of the harshness by my siblings and my parents. It’s similar to Elwood, who’s able to have this outlook and grow into his morality because he was shielded from certain things that Turner wasn’t, and raised with a lot of love by his grandmother. And so when he starts to develop his political consciousness, he feels like there’s this one way things should work, and it feels obvious to him.”

Like Elwood, Herisse was born in Florida, but he was raised in Massachusetts, in a town called Randolph. Perhaps it’s only the afterglow of the film – seeing his face this close, staring into the webcam lens, is a bit disorienting after my two back-to-back viewings of the film – but the memories he recalls feel somehow Nickel Boys-esque: squelching into the backseat as he waits for the car to warm in the winter months, his father clearing snow off the window; the chorus of voices and laughter from his aunts, uncles and cousins in the house, always packed with relatives; the Saturdays spent on the hardwood floors of his family friend’s studio, where his parents would ballroom dance all night and where he was left to play with the other kids. “My dad’s side of the family was pretty artistic: my late aunt was a talented singer, and my grandpa plays the guitar, the piano, and sings.”

Their artistic predilections may have contributed to his love for performance, but he can also trace it back to another, less likely scene. “Man, Step Up – you ever seen that?” he asks. (Of course I have seen Step Up. I am a gay man with a mother who dances salsa and kizomba.) “I feel like that was the real catalyst,” he says. He liked to dance with his sister and his cousins, perform for their families like they’d been torn from the fabric of the movie, and eventually they developed a love for music videos, then Dancing with the Stars. But Herisse always thought he would be a basketball player, until he accompanied his pageant-girl sister to some acting classes and decided to sign up for himself.

He got hooked, fast. In 2011, he attended an acting showcase in Los Angeles where agents and managers scouted new talent, and he was asked to come back for another. Soon enough, his parents were taking him to representation meetings, and he has a clear memory of the serious discussion they staged in their living room. “They sat me down and they were like, ‘Alright, do you really want to do this? Is this your dream?’ I think I was 11 at the time. I wanted my cousins to see me on Nickelodeon.” He said yes, and there was no doubt: they moved to Los Angeles. “As I get older, I realise how incredible that is – how they were willing to sacrifice so much for me,” he says.

In middle school, Herisse went to auditions between classes. He did show choir, played Seaweed J Stubbs in his sophomore year production of Hairspray, and slowly it dawned on him that his love of performance was not evaporating with age. It didn’t hurt, either, that being on stage was the first time girls really noticed him. When he was 17, he had his first big break, in Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us. He was cast as Yusef Salaam, who was only 15 years old when he was wrongly convicted and imprisoned for seven years for the rape and assault of a white woman in Central Park. “It was my first introduction to understanding what I was capable of,” he says dreamily. It was also his first time in New York City, and he was on a set with the likes of Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor (who played his mother, and who plays his grandmother in Nickel Boys), Jharrel Jerome (post-Moonlight), Joshua Jackson, and the late Michael K Williams. “I just felt like, if I’m in this space, it’s gotta mean something,” says Herisse.

Like Nickel Boys, When They See Us introduced Herisse to a fragment of American life that he had not been privy to, and that he hadn’t realised was so near to the present. (The Central Park Five were not exonerated until 2002; Dozier School wasn’t shut down until 2011.) “It was so weird, seeing the Exonerated Five, these gentle souls, and knowing that this happened to them – that it could happen to any of us,” says Herisse. “I didn’t realise the gravity of it all until I met Yusef. I was a bit intimidated to meet his mom. I remember thinking, ‘I hope I actually look like him.’ I remember when he stepped into the room for that meeting, he just had the biggest smile on his face, and this pleasant aura, and we hugged and I thought, ‘There’s no way this happened to you. If this is how you are now, after everything you’ve suffered through, what did they take from you?’ He told me about his dreams as a kid, how he was interested in fashion. For all of these guys, it’s like the world was at their fingertips, and then the worst possible thing happened.” It’s a shame, says Herisse, that he’s had to learn about these darker corners of history through performance, instead of in class. “But it’s a privilege and an honour to be able to bring them to light so other people can learn about them,” he says. “I’m thankful to be learning alongside everyone else.”

However, Herisse is not planning to bear the whole weight of African-American history in every performance. “My manager made a joke the other day where she was like, ‘If someone asks about you for a project, I have to ask, ‘Well, is it heavy? Will something awful happen to him?’ If the answer is yes, then I know you’ll probably do it.’” He laughs. Working with Ross on Nickel Boys has been formative for him, just as working with DuVernay was, and he speaks about his castmates and directors with palpable reverence. Still, he’s excited to see what other opportunities open themselves up to him now, in a world where Nickel Boys was an Oscar nominee for Best Picture. He’s already made fans of so many people he admires: Sean Baker, Denis Villeneuve (one of his favourite working directors), Jeremy Strong, Sebastian Stan, the whole cast of The Piano Lesson. He’d love to do a comedy with Ayo Edebiri, whom he met while she was leaving a screening of Nickel Boys. “I don’t really know what’s next,” he says. “It’s so crazy to think that all of this is happening at 24, because I never would have thought … ” A call from his girlfriend interrupts him.

For now, Herisse is going to wait. After this call, he’s probably going to play Marvel Rivals with his friends. He hasn’t been to the movies in a while, or just laid on a hammock and watched the clouds pass. And he wants to get better at taking care of his plants. He’s in the process of overwintering the seeds for a bonsai tree, from a kit his friend bought him in Japan. “My biggest dream,” he says, “is to one day own a greenhouse.” For now, Herisse is busy cultivating his own garden.

Hair: Johnnie Sapong at The Wall Group. Make-up: Alana Palau. Talent: Ethan Herisse. Set design: Jeremy Reimnitz at Spencer Vrooman Studio. Casting: Greg Krelenstein. Photographic assistants: Tyler Adams and Tristan Hirsch. Styling assistant: Megan King. Hair assistant: Matthew Leadabrand. Production: Wes Olson at Connect The Dots. Production manager: Nicole Morra. Production assistants: Mateo Calvo and Khari Cousins

This story is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from April 24.

Film by Martine Syms. Editing by Alice Wade

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageEthan Herisse wears Prada AW25Photography by Martine Syms, Styling by Julie Ragolia

This story is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from April 24.

Ethan Herisse was not expecting a callback. The chemistry read, he thought, had gone well enough by most metrics. They gelled. It felt good. But when it was over, the director for Nickel Boys, RaMell Ross, who had beamed into the audition room via Zoom, said to Brandon Wilson, “OK, Brandon – I’ll talk to you later,” and to Herisse he said, “Goodbye.”

“I was just like, ‘Damn, right in front of me like that is craaazy,’” jokes the 24-year-old, glancing around his bedroom in mock exasperation. The room is dark, lit only by a bedside lamp behind him and the glow of the computer screen reflected in his silver glasses, but I can make out a couple of items: movie posters above the bed, a street sign that reads “DO NOT ENTER: WRONG WAY”, another, beneath it, that says “BENVENUE ST”. He’s dressed in a greyish-blue zip-up chambray shirt – which he occasionally uses to clean his lenses – silver hoops in his ears, and a thin, silver chain around his right wrist.

Wilson, he says, who had already done a read with a different actor by the time he met Herisse, was sure this one was it, that some covalent bond had spontaneously formed between them in that room and they would be making the movie together, but Herisse wasn’t so sure. “Brandon’s a lot more confident than me about that sort of thing,” he says. For a young actor at the beginning of his career, much of the invisible administrative work involves inoculating the ego against rejection, bracing constantly for bad news like a traumatised survivalist. The breakout, ever dreamed about, is always deferred.

And he’d been excited about the script, this balletic meditation on trauma, memory, the machinery of American racism, the nuances of Black male friendship, and the boundaries between the self and the Other. “I had already read The Underground Railroad, and really liked it,” says Herisse, who is naturally interested in the embarrassing, under-examined aspects of American history — stories, jettisoned into the the dark corners of the public imagination, that reveal to him his own ignorance, his own belated encounters with slavery’s many afterlives. Ross’s film, set in 1960s Florida and adapted from the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Colson Whitehead, follows the tragedy of Elwood Curtis, a brilliant, idealistic young student whose life is upended when he’s interned at an abusive “reform school” for hitching a ride, accidentally, in a stolen Pontiac. At Nickel Academy – based on the real-life Dozier School for Boys, where Black boys as young as eight could be held for “charges” as innocuous as truancy and where, in 2019, dozens of graves were discovered – Elwood is befriended by Turner (Wilson), a cynical, charismatic boy around his age who defends him and shows him the ropes, including literal, frayed ones used for lynchings in the forest. At Nickel Academy, the boys attempt to keep each other alive.

A couple of days after the audition, Herisse’s phone buzzed. He was in class at UC Irvine. It’s difficult to speak to your manager about the results of a chemistry read when you’re being bombarded with a lesson on actual, molecular chemistry – particularly when it’s an arduous course exploring the synthesis and behaviours of inorganic compounds, whatever that means – and so Herisse, who was in the home stretch of his degree, declined the call like a good, responsible student. “We were only a few weeks in, and I was already getting my ass beat,” he admits. (Studying chemistry, not acting, is the hardest thing he’s ever done.) But his manager insisted it was an emergency, and when he excused himself to ring her back, she patched his agent and his parents onto the call. “I walked back into that classroom, and I didn’t take a single other note,” says Herisse. “I sat down, turned to my friend, and was like, ‘I’m not coming back for the rest of the quarter. See you later!’” Obviously, he got the part. It was the best drive home of his life.

Ethan Herisse is not new to the camera though. He’s been acting in some form or another since he was 11 years old, when he chaperoned his younger sister to her acting classes and then decided he wanted to perform, too. There were other gigs before this one, small TV parts in The Mindy Project and Key & Peele and Chicago Med, and back in 2019, he had to take a furlough from his studies to film Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us, a harrowing miniseries based on the infamous case of the Central Park Five. But Nickel Boys promised to be different, his first lead role on the big screen.

And it’s an ambitious gambit. Probably, most actors do not expect their breakthrough roles to be for films in which they hardly ever appear directly. (“I like the movie,” a friend sheepishly told him after seeing it. “I just wish I saw your face more.”) But Ross, a six-foot-six former basketball player and current professor of visual art at Brown University, wanted to adapt the story through an impressionistic, experimental prism, and has rendered it in a collage-like accretion of sensual, first-person images. “Make the camera an organ,” he wrote in Renew the Encounter, a 2019 manifesto on photography and the white gaze. “Take it into your body. Shoot toward a personal poetics.”

What we witness, then, is a big bang of subjectivity, the extraordinary birth of a consciousness and the requisite storm of darkening images that breach the Black child’s innocence: glittering, falling ribbons of Christmas tinsel, a boozy house party witnessed at table level, the open face of a sermonising Martin Luther King in a stack of storefront televisions – each memory is swept away, gradually and then all at once, by hand-drawn lynching cartoons scrawled in a textbook, the hard partition in the back of a police car, an orange grove refashioned into a contemporary plantation. We don’t actually see Elwood until 36 minutes of the film have elapsed, and when we finally do, in a breathtaking body-jump that replays, from Turner’s perspective, a scene we have just witnessed, Herisse conveys to us the exact shape of Elwood’s deflation: his posture is resigned, his eye contact furtive, his voice slightly trembling. He cried when he first watched it back with his parents, hardly recognised himself until the credits rolled. His dad was speechless. “You need to do a comedy next,” his mother told him. (When They See Us is not exactly Sunday morning viewing, either.) She has gone back to watch it again three other times. His dad went back twice.

The net effect of the film is devastating, but the experience of shooting it was not. Ross, he says, has a curious, relaxed way of working. He would sometimes see Herisse meandering around, playing with a spider web or wrapping a string around his finger, and then he would put it in the film. In this way, the film becomes, at times, a reflection of its lead actor’s own sensitivities, his own particular gaze. He got really close with his co-star, Wilson, and that intimacy somehow suffuses the movie, though they appear together in just one single, breathtaking frame over the course of the whole two hours. The crew shot Nickel Boys in New Orleans, and the week they were supposed to begin, Ross got Covid. “For the week that production was shut down, B and I were just, like, roaming the city,” says Herisse. They went to the movies and saw Tár (Wilson’s favourite), Bones & All (Herisse’s favourite), and The Banshees of Inisherin (neither of their favourites, but they liked it). They went to Bourbon and Frenchmen Streets, had their senses overwhelmed by drunken chaos and the swell of jazz music.

“My manager made a joke the other day where she was like, ‘If someone asks about you for a project, I have to ask, ‘Well, is it heavy? Will something awful happen to him?’ If the answer is yes, then I know you’ll probably do it’” – Ethan Herisse

And they went to Waffle House. “Bro, Brandon does not play about Waffle House,” he says. It was Wilson who introduced Herisse to Waffle House, and eventually, the pair established Waffle House Mondays: whenever they would wrap shooting on a Monday, they’d find the nearest one and invite everyone. (Herisse would get the All Star Special. Ross would get six eggs and grits. In college, they called him Six Eggs. Eventually, he brought it down to five.)

The boys of Nickel Boys represent a political philosophy divided, a bond that turns out to be ionic. Elwood, a disciple of King, is righteous and a little bit romantic, a near- unwavering believer in one man’s capacity to change a world intent to destroy him; Turner, who has been at Nickel for longer, whose alcoholic mother abandoned him, is more of a defeatist, having witnessed so much degradation and found no salve or solution. “When I was reading the script, I was seeing Elwood as I saw myself at 16,” says Herisse.

“I’ve always been an optimistic person. I think I have this wide-eyed, naïve outlook on the world, and I’ve always been protected from a lot of the harshness by my siblings and my parents. It’s similar to Elwood, who’s able to have this outlook and grow into his morality because he was shielded from certain things that Turner wasn’t, and raised with a lot of love by his grandmother. And so when he starts to develop his political consciousness, he feels like there’s this one way things should work, and it feels obvious to him.”

Like Elwood, Herisse was born in Florida, but he was raised in Massachusetts, in a town called Randolph. Perhaps it’s only the afterglow of the film – seeing his face this close, staring into the webcam lens, is a bit disorienting after my two back-to-back viewings of the film – but the memories he recalls feel somehow Nickel Boys-esque: squelching into the backseat as he waits for the car to warm in the winter months, his father clearing snow off the window; the chorus of voices and laughter from his aunts, uncles and cousins in the house, always packed with relatives; the Saturdays spent on the hardwood floors of his family friend’s studio, where his parents would ballroom dance all night and where he was left to play with the other kids. “My dad’s side of the family was pretty artistic: my late aunt was a talented singer, and my grandpa plays the guitar, the piano, and sings.”

Their artistic predilections may have contributed to his love for performance, but he can also trace it back to another, less likely scene. “Man, Step Up – you ever seen that?” he asks. (Of course I have seen Step Up. I am a gay man with a mother who dances salsa and kizomba.) “I feel like that was the real catalyst,” he says. He liked to dance with his sister and his cousins, perform for their families like they’d been torn from the fabric of the movie, and eventually they developed a love for music videos, then Dancing with the Stars. But Herisse always thought he would be a basketball player, until he accompanied his pageant-girl sister to some acting classes and decided to sign up for himself.

He got hooked, fast. In 2011, he attended an acting showcase in Los Angeles where agents and managers scouted new talent, and he was asked to come back for another. Soon enough, his parents were taking him to representation meetings, and he has a clear memory of the serious discussion they staged in their living room. “They sat me down and they were like, ‘Alright, do you really want to do this? Is this your dream?’ I think I was 11 at the time. I wanted my cousins to see me on Nickelodeon.” He said yes, and there was no doubt: they moved to Los Angeles. “As I get older, I realise how incredible that is – how they were willing to sacrifice so much for me,” he says.

In middle school, Herisse went to auditions between classes. He did show choir, played Seaweed J Stubbs in his sophomore year production of Hairspray, and slowly it dawned on him that his love of performance was not evaporating with age. It didn’t hurt, either, that being on stage was the first time girls really noticed him. When he was 17, he had his first big break, in Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us. He was cast as Yusef Salaam, who was only 15 years old when he was wrongly convicted and imprisoned for seven years for the rape and assault of a white woman in Central Park. “It was my first introduction to understanding what I was capable of,” he says dreamily. It was also his first time in New York City, and he was on a set with the likes of Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor (who played his mother, and who plays his grandmother in Nickel Boys), Jharrel Jerome (post-Moonlight), Joshua Jackson, and the late Michael K Williams. “I just felt like, if I’m in this space, it’s gotta mean something,” says Herisse.

Like Nickel Boys, When They See Us introduced Herisse to a fragment of American life that he had not been privy to, and that he hadn’t realised was so near to the present. (The Central Park Five were not exonerated until 2002; Dozier School wasn’t shut down until 2011.) “It was so weird, seeing the Exonerated Five, these gentle souls, and knowing that this happened to them – that it could happen to any of us,” says Herisse. “I didn’t realise the gravity of it all until I met Yusef. I was a bit intimidated to meet his mom. I remember thinking, ‘I hope I actually look like him.’ I remember when he stepped into the room for that meeting, he just had the biggest smile on his face, and this pleasant aura, and we hugged and I thought, ‘There’s no way this happened to you. If this is how you are now, after everything you’ve suffered through, what did they take from you?’ He told me about his dreams as a kid, how he was interested in fashion. For all of these guys, it’s like the world was at their fingertips, and then the worst possible thing happened.” It’s a shame, says Herisse, that he’s had to learn about these darker corners of history through performance, instead of in class. “But it’s a privilege and an honour to be able to bring them to light so other people can learn about them,” he says. “I’m thankful to be learning alongside everyone else.”

However, Herisse is not planning to bear the whole weight of African-American history in every performance. “My manager made a joke the other day where she was like, ‘If someone asks about you for a project, I have to ask, ‘Well, is it heavy? Will something awful happen to him?’ If the answer is yes, then I know you’ll probably do it.’” He laughs. Working with Ross on Nickel Boys has been formative for him, just as working with DuVernay was, and he speaks about his castmates and directors with palpable reverence. Still, he’s excited to see what other opportunities open themselves up to him now, in a world where Nickel Boys was an Oscar nominee for Best Picture. He’s already made fans of so many people he admires: Sean Baker, Denis Villeneuve (one of his favourite working directors), Jeremy Strong, Sebastian Stan, the whole cast of The Piano Lesson. He’d love to do a comedy with Ayo Edebiri, whom he met while she was leaving a screening of Nickel Boys. “I don’t really know what’s next,” he says. “It’s so crazy to think that all of this is happening at 24, because I never would have thought … ” A call from his girlfriend interrupts him.

For now, Herisse is going to wait. After this call, he’s probably going to play Marvel Rivals with his friends. He hasn’t been to the movies in a while, or just laid on a hammock and watched the clouds pass. And he wants to get better at taking care of his plants. He’s in the process of overwintering the seeds for a bonsai tree, from a kit his friend bought him in Japan. “My biggest dream,” he says, “is to one day own a greenhouse.” For now, Herisse is busy cultivating his own garden.

Hair: Johnnie Sapong at The Wall Group. Make-up: Alana Palau. Talent: Ethan Herisse. Set design: Jeremy Reimnitz at Spencer Vrooman Studio. Casting: Greg Krelenstein. Photographic assistants: Tyler Adams and Tristan Hirsch. Styling assistant: Megan King. Hair assistant: Matthew Leadabrand. Production: Wes Olson at Connect The Dots. Production manager: Nicole Morra. Production assistants: Mateo Calvo and Khari Cousins

This story is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from April 24.

Film by Martine Syms. Editing by Alice Wade

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.