Rewrite

Lead ImagePeter Hujar, La marchesa Fioravanti, 1963© The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (Ars), Ny

Performance and Portraiture / Italian Journeys, a new exhibition of Peter Hujar’s photography at the Centro Pucci gallery in Prato, is the latest in a series of major retrospectives devoted to the once-neglected photographer. Even during his professional heyday in the 1970s and 80s, when he enjoyed quiet acclaim and was championed by Susan Sontag, Hujar led a life of ascetic poverty (washing his clothes by hand in the sink, sometimes surviving on hor d’oeuvres handed out at parties) which was almost, but not quite, deliberate. He resented being poor but seemed to sabotage every opportunity for financial advancement which came his way, whether through his notorious temper or an obstinate refusal to compromise his creative vision, even while working on commercial projects. When Hujar died of an AIDS-related illness in 1987, he was more or less penniless.

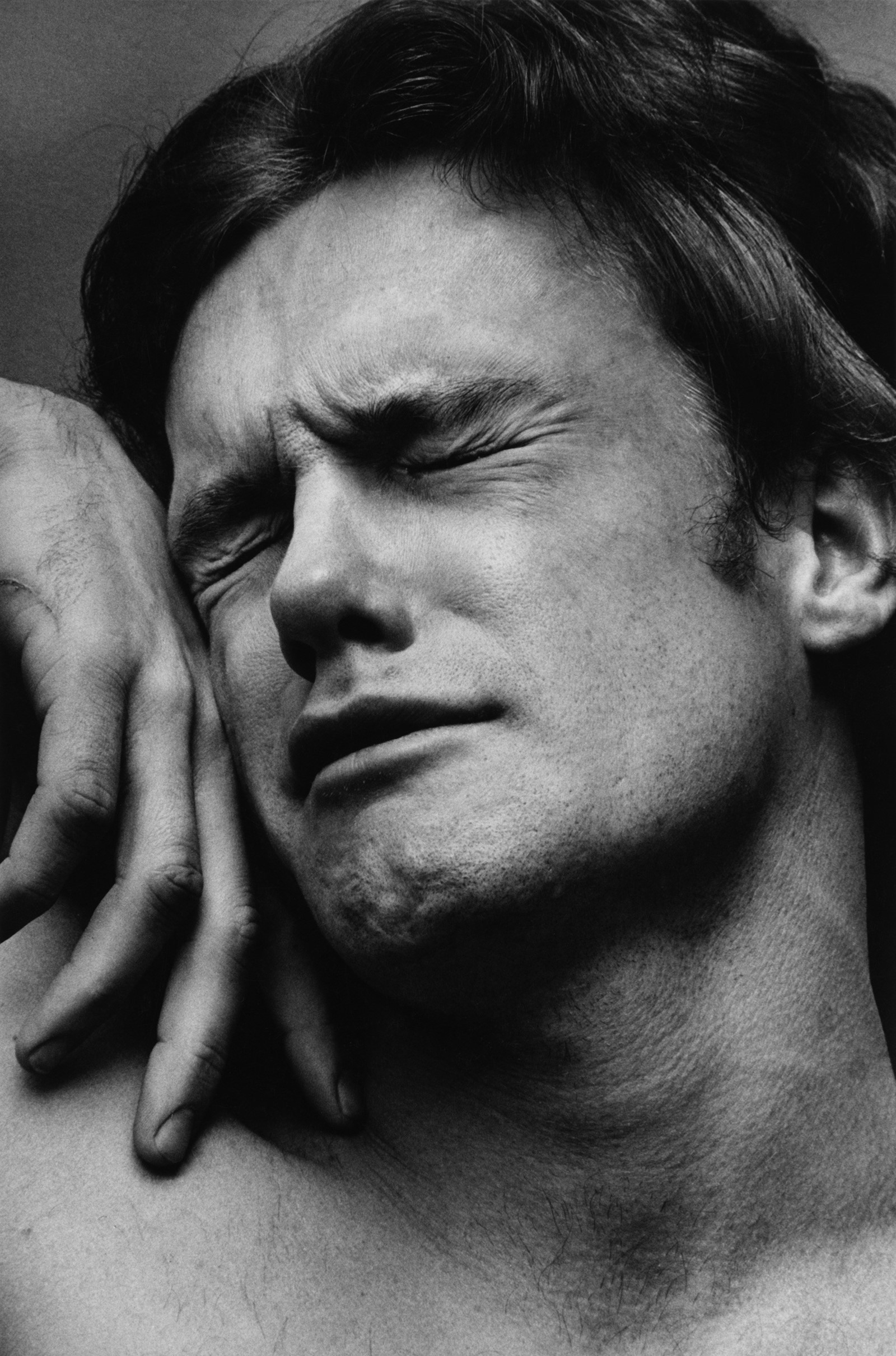

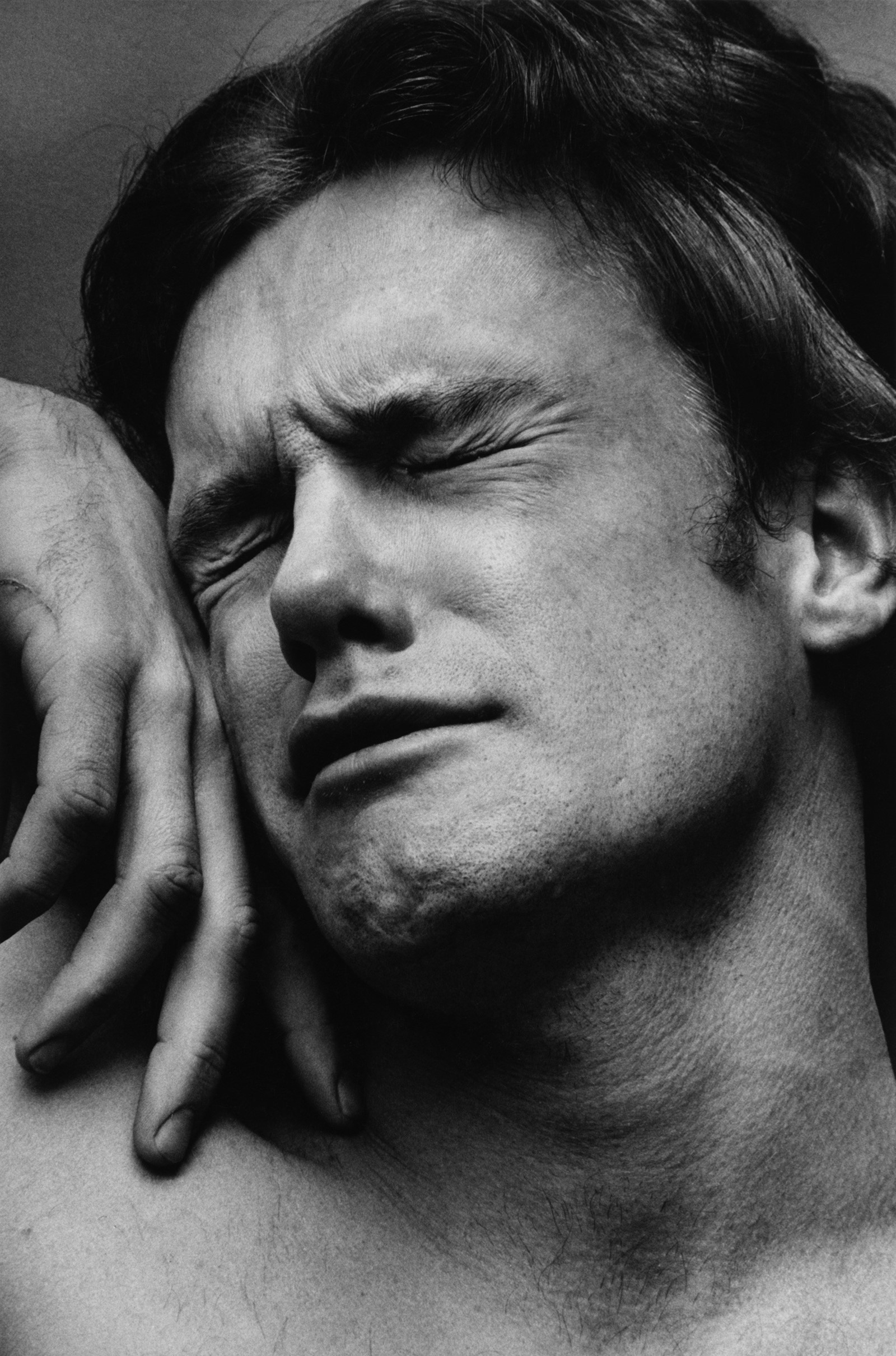

But Hujar always suspected that his work would enjoy greater acclaim after his death, and he was right. His stock has continued to rise over the last two decades, his prints now selling at top auction houses for tens of thousands of dollars, and a handful of his images have permeated culture to the point of being instantly recognisable. One of the earliest iterations of the Hujar renaissance came in 2005 when his arrestingly beautiful portrait of drag queen Candy Darling on her hospital deathbed was used as the album cover for Anohni and the Johnsons’ I Am a Bird Now. Cynthia Carr’s A Fire In The Belly, a masterful biography of David Wojnarowicz and the downtown arts scene of the 70s and 80s, in which Hujar features heavily, was published in 2013, marking the beginning of an intense wave of interest in the art of the Aids crisis which would continue throughout the decade and further bolster Hujar’s standing. In 2015, one of his three Orgasmic Man portraits graced the cover of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, which was to become a best-selling literary sensation, and two years later the Morgan Gallery in New York staged the first major retrospective of his work: Peter Hujar: Speed of Light. Next week, a large exhibition of his work will open at Raven Row in London.

While we are yet to see any Hujar-themed collections at H&M or posthumous collaborations with high-end luggage brands, he was referenced last year at Loewe’s Spring/Summer 2025 show at Paris Fashion Week; designer Helmut Lang has previously released a limited-edition T-shirt range bearing his photographs. A biopic, Peter Hujar’s Day, will be released later this year, directed by Ira Sachs (Passages) and starring Ben Whishaw. In a more abstract sense, Hujar has joined the pantheon of 20th-century queer artistic icons, finally catching up with contemporaries like Keith Haring and Robert Mapplethorpe (a rival) who eclipsed his success at the time.

Centro Pecci’s new exhibition, Performance and Portraiture / Italian Journeys, shows the breadth of Hujar’s relatively short career, with a particular emphasis on his photographs of the performance scene in 70s New York and his travels through Italy, taking in animals, corpses, urban scenes and pastoral landscapes.

In Susan Sontag’s introduction to Hujar’s 1976 monograph Portraits in Life and Death (the only book he published in his lifetime), she wrote that “photography converts the whole world into a cemetery” and that “Peter Hujar knows that portraits in life are always, also, portraits in death.” This interplay is present most explicitly in the first room of the exhibition, which displays the photographs Hujar took at the Palermo Catacombs, where the bodies are clothed and in various degrees of decay, from skeletons to mummies.

You don’t need to be a visionary to capture the macabre quality of the Catacombs, but Hujar draws out a remarkable expressiveness from its inhabitants. One of them appears to be staring directly into the camera, in a state of repose similar to so many of Hujar’s living subjects. There is a clear parallel between these shots and the portraits on display in the same room, many of them depicting Hujar’s friends, beautiful and very much alive: David Wojnarowicz for instance, his eyes drooping and mouth slightly ajar, looking impossibly sultry as he lounges on a chair.

Many of Hujar’s subjects were queer artists and performers, who lived in New York during one of the city’s most generative, if impoverished, historical periods. This placed many of them in the strange position of being at the absolute forefront of culture while simultaneously existing on the margins of society, stigmatised and often poor. Hujar’s attitude, however, towards these people was one of pure respect. “The people I photograph are not freaks or curiosities to me,” he once said (unlike, say, Diane Arbus, who did refer to her subjects as “freaks”). There isn’t a sense of distance between Hujar and his subjects; they are not strange or uncanny to him; his gaze is one of kinship rather than anthropological curiosity.

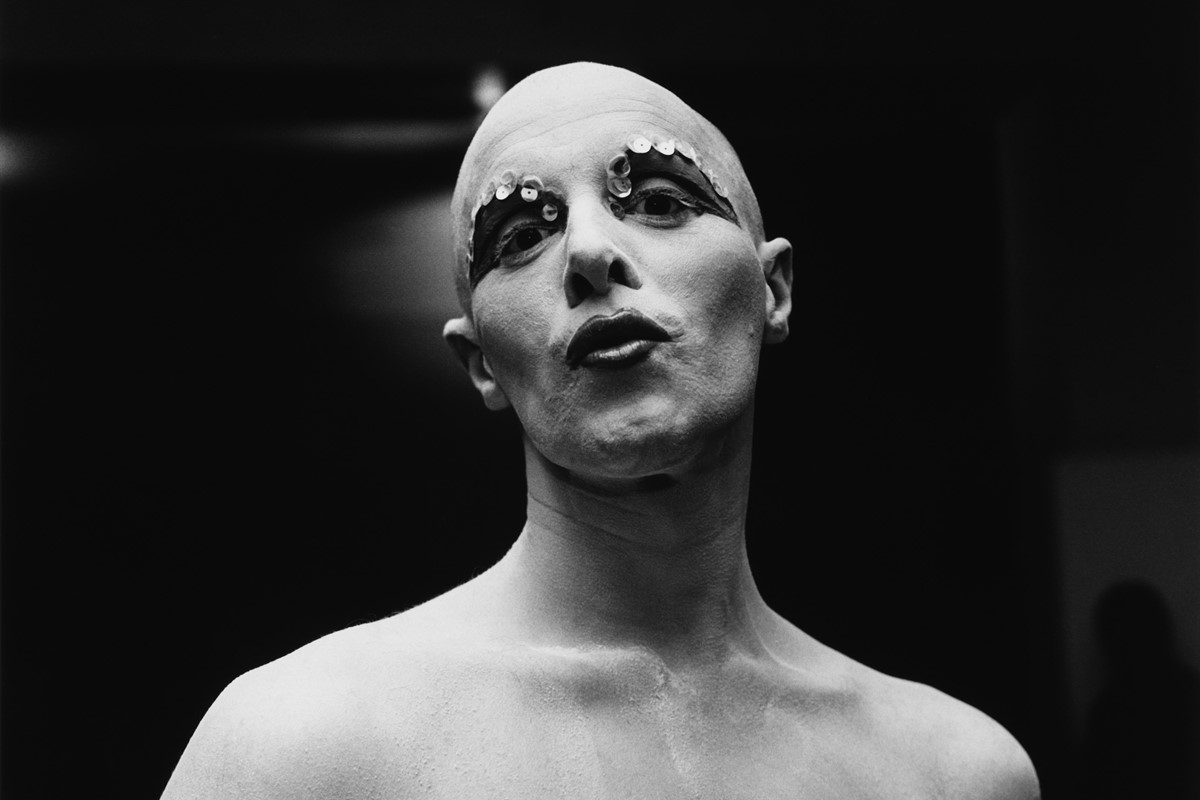

One of the exhibition’s rooms is devoted to Hujar’s shots of the downtown performance scene in the 70s, encompassing punk gigs, drag shows and radical theatre. Larry Ree Backstage (1973), which shows the ballet dancer Larry Ree pouting in full make-up, uses the same stark chiaroscuro of many of Hujar’s studio shots. Like much of his work, it bestows the stately dignity of traditional portraiture on the kind of people (queer, gender non-conforming) who were often denied any dignity and portrayed as trivial, grotesque or ridiculous. A similarly elegant composition is brought to bear in John Flowers Backstage at Palm Casino Review (1974), which presents a far more chaotic scene: Flowers, in full drag and devil horns, squats on a toilet with a wild grin and a cigarette dangling from his lips. Hujar captures the downtown scene with real energy, vitality and affection.

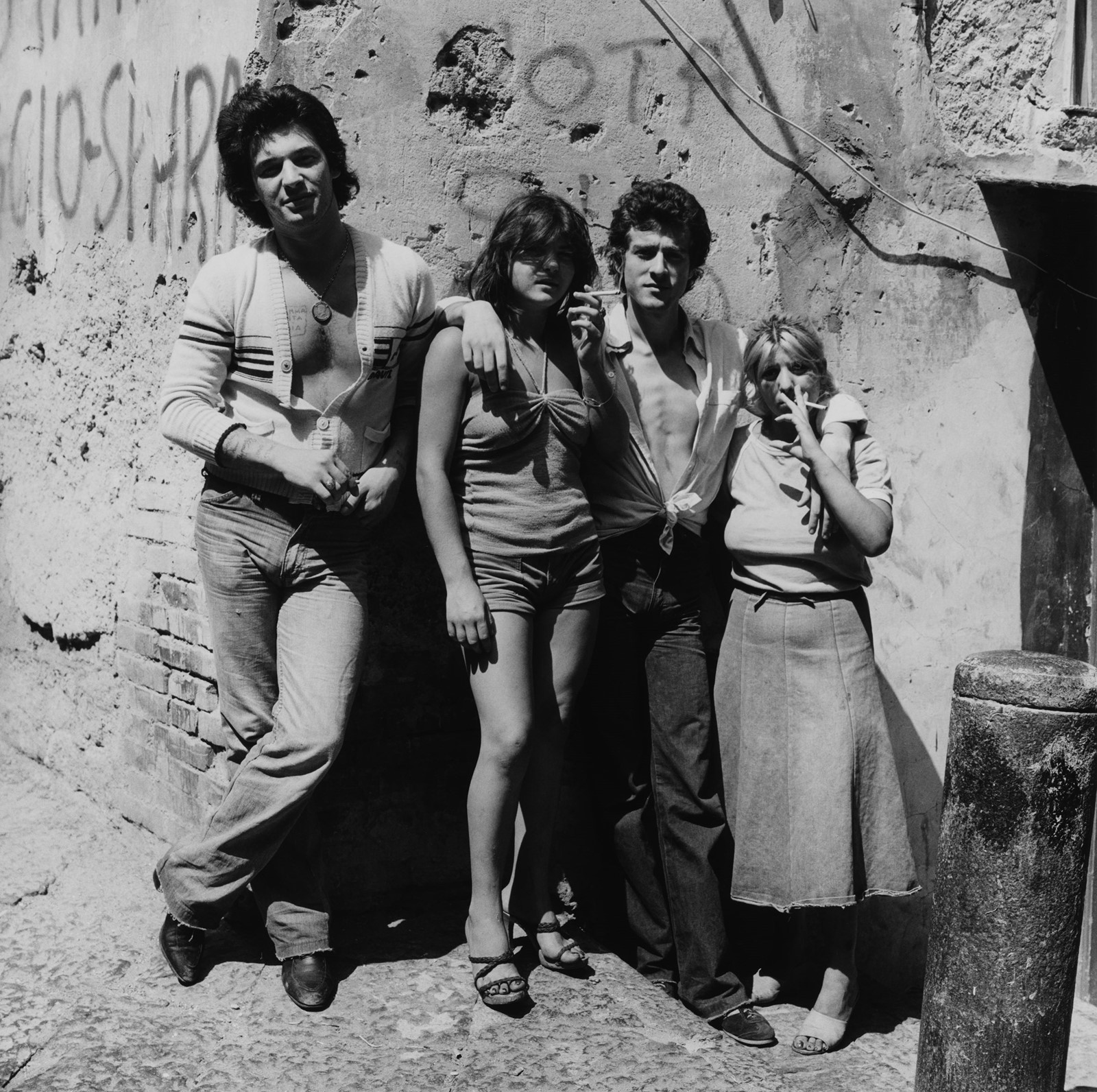

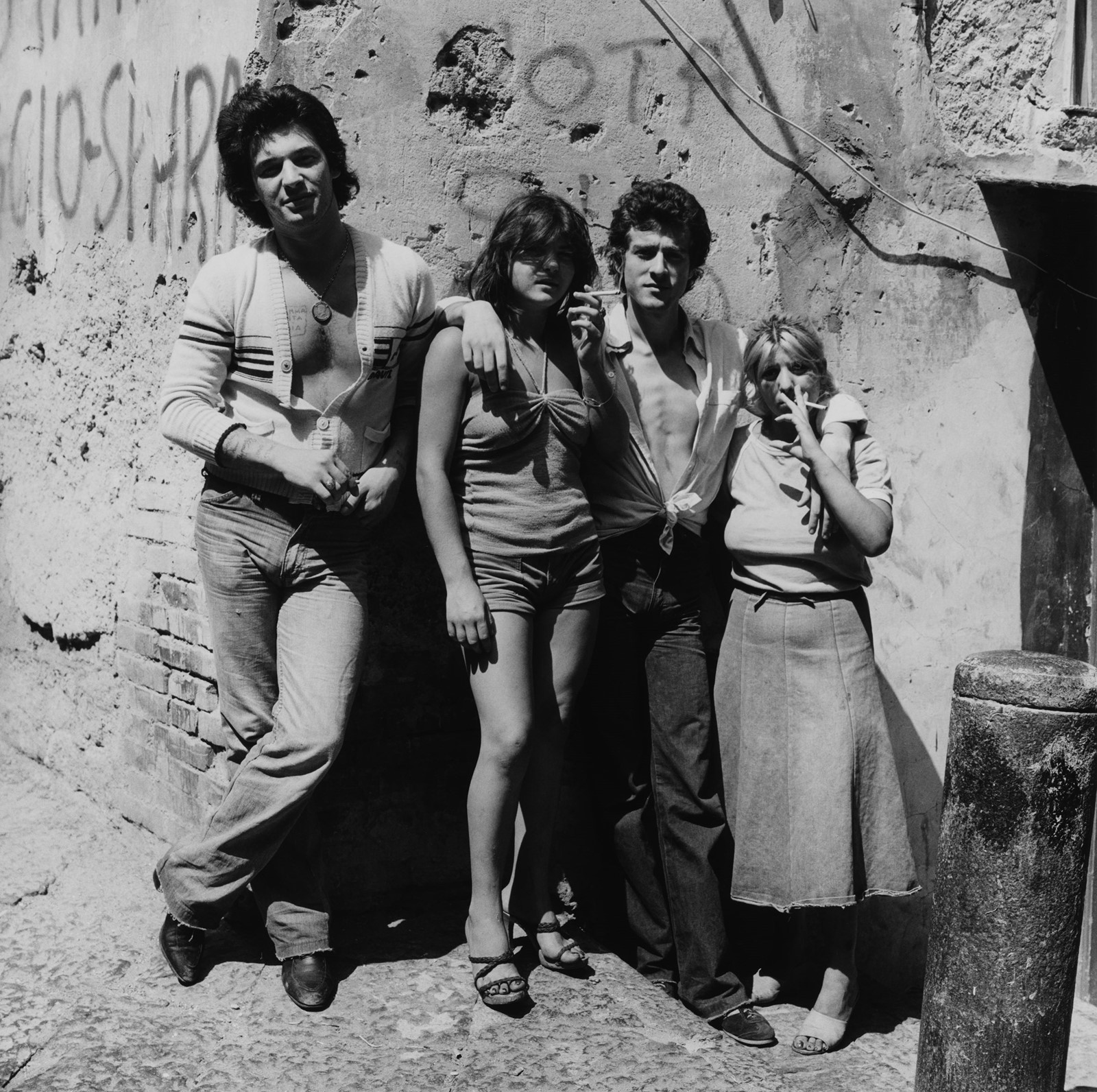

The final room of the exhibition displays photographs that Hujar took during several trips to Italy he took between the 50s and 70s, offering a different perspective on an artist whose work is so indelibly associated with New York. Here we see Hujar stripped of his famous friends, the glamorous if grungy milieu he inhabited and the slick technical mastery he was able to exert in his studio. We see different sides to post-war Italy, from bucolic gardens to grimy, squalid streets. There are several portraits of animals, a practice Hujar was drawn to throughout his career: in Dog in a Doghouse (1978) a rather mournful Dalmation stares reproachfully into the camera as though dreaming of escape, while Colt With Mother (1978) seems to convey a kind of gangly, adolescent diffidence. Hujar captures these animals as living, feeling beings but without ever resorting to cheap anthropomorphism.

Like many of his contemporaries, Hujar has today been subsumed into a glossy Instagram aesthetic, a kind of queer nostalgia suggestive of tasteful melancholy and a bygone age of bohemianism. But Centro Pecci’s exhibition shows that there’s far more to his work than that. Ambitious and formally experimental, beautiful and emphatic, his images are as resonant today as they ever were.

Performance and Portraiture / Italian Journeys by Peter Hujar is on show at Centro Pecci in Prato until 11 May 2025.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImagePeter Hujar, La marchesa Fioravanti, 1963© The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (Ars), Ny

Performance and Portraiture / Italian Journeys, a new exhibition of Peter Hujar’s photography at the Centro Pucci gallery in Prato, is the latest in a series of major retrospectives devoted to the once-neglected photographer. Even during his professional heyday in the 1970s and 80s, when he enjoyed quiet acclaim and was championed by Susan Sontag, Hujar led a life of ascetic poverty (washing his clothes by hand in the sink, sometimes surviving on hor d’oeuvres handed out at parties) which was almost, but not quite, deliberate. He resented being poor but seemed to sabotage every opportunity for financial advancement which came his way, whether through his notorious temper or an obstinate refusal to compromise his creative vision, even while working on commercial projects. When Hujar died of an AIDS-related illness in 1987, he was more or less penniless.

But Hujar always suspected that his work would enjoy greater acclaim after his death, and he was right. His stock has continued to rise over the last two decades, his prints now selling at top auction houses for tens of thousands of dollars, and a handful of his images have permeated culture to the point of being instantly recognisable. One of the earliest iterations of the Hujar renaissance came in 2005 when his arrestingly beautiful portrait of drag queen Candy Darling on her hospital deathbed was used as the album cover for Anohni and the Johnsons’ I Am a Bird Now. Cynthia Carr’s A Fire In The Belly, a masterful biography of David Wojnarowicz and the downtown arts scene of the 70s and 80s, in which Hujar features heavily, was published in 2013, marking the beginning of an intense wave of interest in the art of the Aids crisis which would continue throughout the decade and further bolster Hujar’s standing. In 2015, one of his three Orgasmic Man portraits graced the cover of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, which was to become a best-selling literary sensation, and two years later the Morgan Gallery in New York staged the first major retrospective of his work: Peter Hujar: Speed of Light. Next week, a large exhibition of his work will open at Raven Row in London.

While we are yet to see any Hujar-themed collections at H&M or posthumous collaborations with high-end luggage brands, he was referenced last year at Loewe’s Spring/Summer 2025 show at Paris Fashion Week; designer Helmut Lang has previously released a limited-edition T-shirt range bearing his photographs. A biopic, Peter Hujar’s Day, will be released later this year, directed by Ira Sachs (Passages) and starring Ben Whishaw. In a more abstract sense, Hujar has joined the pantheon of 20th-century queer artistic icons, finally catching up with contemporaries like Keith Haring and Robert Mapplethorpe (a rival) who eclipsed his success at the time.

Centro Pecci’s new exhibition, Performance and Portraiture / Italian Journeys, shows the breadth of Hujar’s relatively short career, with a particular emphasis on his photographs of the performance scene in 70s New York and his travels through Italy, taking in animals, corpses, urban scenes and pastoral landscapes.

In Susan Sontag’s introduction to Hujar’s 1976 monograph Portraits in Life and Death (the only book he published in his lifetime), she wrote that “photography converts the whole world into a cemetery” and that “Peter Hujar knows that portraits in life are always, also, portraits in death.” This interplay is present most explicitly in the first room of the exhibition, which displays the photographs Hujar took at the Palermo Catacombs, where the bodies are clothed and in various degrees of decay, from skeletons to mummies.

You don’t need to be a visionary to capture the macabre quality of the Catacombs, but Hujar draws out a remarkable expressiveness from its inhabitants. One of them appears to be staring directly into the camera, in a state of repose similar to so many of Hujar’s living subjects. There is a clear parallel between these shots and the portraits on display in the same room, many of them depicting Hujar’s friends, beautiful and very much alive: David Wojnarowicz for instance, his eyes drooping and mouth slightly ajar, looking impossibly sultry as he lounges on a chair.

Many of Hujar’s subjects were queer artists and performers, who lived in New York during one of the city’s most generative, if impoverished, historical periods. This placed many of them in the strange position of being at the absolute forefront of culture while simultaneously existing on the margins of society, stigmatised and often poor. Hujar’s attitude, however, towards these people was one of pure respect. “The people I photograph are not freaks or curiosities to me,” he once said (unlike, say, Diane Arbus, who did refer to her subjects as “freaks”). There isn’t a sense of distance between Hujar and his subjects; they are not strange or uncanny to him; his gaze is one of kinship rather than anthropological curiosity.

One of the exhibition’s rooms is devoted to Hujar’s shots of the downtown performance scene in the 70s, encompassing punk gigs, drag shows and radical theatre. Larry Ree Backstage (1973), which shows the ballet dancer Larry Ree pouting in full make-up, uses the same stark chiaroscuro of many of Hujar’s studio shots. Like much of his work, it bestows the stately dignity of traditional portraiture on the kind of people (queer, gender non-conforming) who were often denied any dignity and portrayed as trivial, grotesque or ridiculous. A similarly elegant composition is brought to bear in John Flowers Backstage at Palm Casino Review (1974), which presents a far more chaotic scene: Flowers, in full drag and devil horns, squats on a toilet with a wild grin and a cigarette dangling from his lips. Hujar captures the downtown scene with real energy, vitality and affection.

The final room of the exhibition displays photographs that Hujar took during several trips to Italy he took between the 50s and 70s, offering a different perspective on an artist whose work is so indelibly associated with New York. Here we see Hujar stripped of his famous friends, the glamorous if grungy milieu he inhabited and the slick technical mastery he was able to exert in his studio. We see different sides to post-war Italy, from bucolic gardens to grimy, squalid streets. There are several portraits of animals, a practice Hujar was drawn to throughout his career: in Dog in a Doghouse (1978) a rather mournful Dalmation stares reproachfully into the camera as though dreaming of escape, while Colt With Mother (1978) seems to convey a kind of gangly, adolescent diffidence. Hujar captures these animals as living, feeling beings but without ever resorting to cheap anthropomorphism.

Like many of his contemporaries, Hujar has today been subsumed into a glossy Instagram aesthetic, a kind of queer nostalgia suggestive of tasteful melancholy and a bygone age of bohemianism. But Centro Pecci’s exhibition shows that there’s far more to his work than that. Ambitious and formally experimental, beautiful and emphatic, his images are as resonant today as they ever were.

Performance and Portraiture / Italian Journeys by Peter Hujar is on show at Centro Pecci in Prato until 11 May 2025.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.