Rewrite

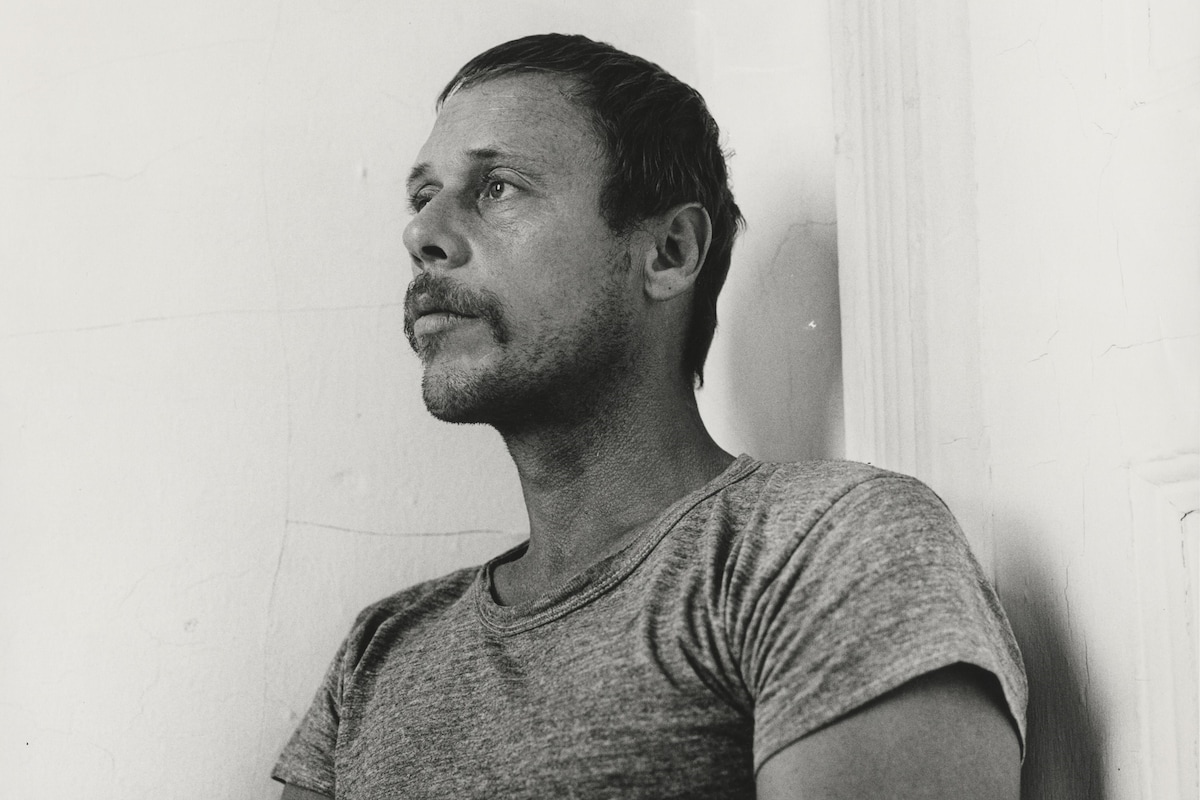

Lead ImagePeter Hujar, Paul Thek (IV), 1975© 2025 The Peter Hujar Archive / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, DACS London. 2025

In 1975, an image of Paul Thek was captured by his then-lover, downtown New York photographer Peter Hujar. Thek wears a grey marl T-shirt, tight at the arms, positioned in profile against a bare wall. Although the photograph is printed in black and white, his skin looks sun-warmed, weathered. He’s beautiful in a classical way, moustached, angular, sweat on his neck. This is the face of one of the most important artists whom no one remembers.

Hujar and Thek were not true habitués of Andy Warhol’s Factory, but in 1964, they sat for Screen Tests, three-minute cinematic talking-head portraits. Their impassive faces would sometimes appear on the walls at Warhol parties, as part of screening events entitled Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys, testifying to Thek’s beauty.

Born in Brooklyn in 1933, Thek was raised in a Catholic family. Later, he became close to Susan Sontag, who dedicated her first book, Against Interpretation (1966), to him. Thek was one of the most radical contemporary artists to emerge during the 1960s, yet his work has been largely unrecognised for decades. Now, Thek’s paintings are on show at Thomas Dane Gallery in London in a new exhibition, Seized by Joy: Paintings 1965–1988, curated by Kenny Schachter and designer Jonathan Anderson.

Here, Kenny Schachter, Lynne Tillman, Andrew Durbin, Gary Schneider, Jack O’Brien, Fiona Anderson, Tarek Lakhrissi, and Francis Schichtel speak on the lasting legacy of Paul Thek.

目次

- 1 Kenny Schachter, Artist, Writer and Curator

- 2 Lynne Tillman, Novelist

- 3 Andrew Durbin, Author and Editor-in-Chief of Frieze

- 4 Gary Schneider, Photographer

- 5 Jack O’Brien, Artist

- 6 Fiona Anderson, Art Historian and Author

- 7 Tarek Lakhrissi, Artist

- 8 Francis Schichtel, Archivist and Photographer

- 9 Kenny Schachter, Artist, Writer and Curator

- 10 Lynne Tillman, Novelist

- 11 Andrew Durbin, Author and Editor-in-Chief of Frieze

- 12 Gary Schneider, Photographer

- 13 Jack O’Brien, Artist

- 14 Fiona Anderson, Art Historian and Author

- 15 Tarek Lakhrissi, Artist

- 16 Francis Schichtel, Archivist and Photographer

Kenny Schachter, Artist, Writer and Curator

“I saw Thek’s Witte de With show in Rotterdam in the mid-90s – The Wonderful World That Almost Was – and I was floored. It was one of the most extraordinary art experiences I’ve ever had, and it’s still so bitterly with me. Those pieces are profound and remain to this day absolutely unprecedented and unparalleled by anything sculpturally that’s come before or after them.

“I’ve been literally coexisting with Paul’s work for more than 30 years. To drive home my point, I took two drawings off the wall from the show, and they’re hanging where I’m staying [in an Airbnb in Spain]. These are beautiful drawings. It’s a two-page self-portrait; he’s in bed, naked. I press my nose up against his work. Some lines are so heavily wrought you can see the lead reflecting where he gouged the surface. Every day, it seizes me with joy. I don’t think a day’s gone by where I haven’t spent a night with Paul Thek, having never met him. And that’s really my love affair.”

Lynne Tillman, Novelist

“The art of Paul Thek, a near-mythical figure, is sui generis. Thek’s brilliant, curious, startling art has rarely been exhibited. This happens to artists who are beyond category; they confound critics, gallerists and collectors. Fortunately, Andrew Durbin’s biography and cultural history of Thek and photographer Peter Hujar will tell the story of their formative years, relationship and aesthetic development. Durbin is doing the important work of excavating Paul Thek’s unique oeuvre.”

“I don’t think a day’s gone by where I haven’t spent a night with Paul Thek, having never met him. And that’s really my love affair” – Kenny Schachter

Andrew Durbin, Author and Editor-in-Chief of Frieze

“In his lifetime, Thek kept more than 125 diaries, in which he copied favourite passages from books, sketched landscapes and lovers and friends and little objects, drafted poems, reflected on his childhood and life, conducted self-interviews, and wrote autofiction. In writing my forthcoming book about Thek and his friend, Peter Hujar, I fell madly in love with Paul’s writing. Lines from his notebooks and letters still return to me as guiding lights.

“Right now, I’m thinking of a phrase from a 1988 painting, one of his last works, made when he was dying: ‘While there’s still time, let’s go out and feel everything.’ Those words capture his attitude as an artist. Keenly aware of the limits placed on any human life, he sought, always, experience. “Reaching out to experience is really so key to joie de vivre,” a friend recently remarked to me after the death of Edmund White, another great lover of life. Thek understood that intuitively, and it guided his work to the very end. His work says, go and live. That is his greatness – and his generosity.”

Gary Schneider, Photographer

“In 1977, when I first visited Peter Hujar’s live/work loft, a large painting hung in the entrance. Paul Thek painted it in 1963 during the height of their romantic relationship. It is a grid composed of 25 fragments of Peter’s face. The Thek painting was included in the Hujar exhibition, Eyes Open in the Dark, that John Douglas Millar and I co-curated at Raven Row in London. I was staying in a flat in the museum and was able to visit the painting every day, which was an emotional experience for me each time. In the painting I had known, the dominant tonality had been an orange, white and muddy black – the accumulation of Peter’s heavy cigarette smoking. The conserved painting has bright whites with inky blacks. I’m grateful that I got to experience it in its original glory.”

Jack O’Brien, Artist

“I still think about the works from Thek’s series Technological Reliquaries – that hand, the pink flesh, the mirrored vitrines. They’re such brutal and devotional objects. He presented a sculptural language that was so lush and so perishable it almost refused to be historicised, but nonetheless, it laid the groundwork for artists like myself. I think about how he staged collapse and camp at the same time, offering a kind of moral choreography for objects, like they were performing their own fragility.

“In my own work, I’ve used impoverished and overly familiar materials – used leather chairs, silver coins, loose cords – trying to tune themselves into something excessive or devotional, but never quite resolved. I think Thek did that with enormous grace. There’s also something in the theatricality – how his installations tilt between ritual and rehearsal – that feels close to me now, especially in thinking about sculpture as stage, prop, or accidental gag.“

Fiona Anderson, Art Historian and Author

“Seeing some of the Technological Reliquaries in person for the first time at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 2010, I was caught off guard by their strange, intermediate size, evoking something between farm animal and human being, and by their tenderness and their humour.

“The small scale of La Corazza di Michelangelo (1963), a cheap souvenir reproduction of an armoured Roman breastplate (bought in Italy with the photographer Peter Hujar) encrusted with lumps of wax and red acrylic paint, moved me in particular. It was compelling, disgusting, and sexy. Thek made this work after visiting the Palermo catacombs with Hujar and, as he famously told the critic Gene Swenson in 1966, picking up what he thought was a piece of paper and finding it crumble in his hand, realised it was a piece of dried thigh. In La Corazza, the boundaries between ancient history and Thek’s present, pain and pleasure, disgust and attraction, self and other, collapse. Thek’s sculptures offer a queer way of thinking about bodies and sculpture in 1960s America. But in their tender humour and sense of play and pleasure, they elude straightforward scholarly analysis, too. As Thek’s friend Susan Sontag argued: ‘In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art’.”

“Thek is less an influence than a companion: someone who opened the door for queer aesthetics to be both wounded and luminous, or bright” – Tarek Lakhrissi

Tarek Lakhrissi, Artist

“Paul Thek’s work resonates deeply with my own practice, especially in how he embraces fragility, spirituality, and the body as sites of resistance and transformation. As a queer artist working across video, sculpture, and poetry, I see in Thek a kind of spiritual predecessor, someone who dared to make the vulnerable sacred. Like Thek, I often draw on language, myth, and ritual to confront dominant narratives and imagine alternative futures. Thek is less an influence than a companion: someone who opened the door for queer aesthetics to be both wounded and luminous, or bright.”

Francis Schichtel, Archivist and Photographer

“I came to Paul Thek through my work at the Peter Hujar Archive where I scanned all of Hujar’s negatives. In a small, windowless storage unit, I spent three years going through each roll shot by Peter. I remember coming across his photos where Thek first appears in 1956, in Coral Gables. The images are tender, curious, and there’s a beauty in the way they explored each other. I followed their travels through Italy, trips to Fire Island, and watched both of their artistic practices evolve. Their powerful relationship is right there in pictures. I was so moved by Thek’s gorgeous face and the way Peter saw him. And there was something in the way I imagined they lived that inspired me.

“I later discovered Thek’s letters to Hujar, and was totally riveted. Their romance, playfulness, charm, and humility were captivating, and it put words to the images and relationship I spent so much time looking at. The letters read like a novel. Paul Thek and Peter Hujar: Stay Away from Nothing will be coming out this autumn, published by Primary Information. It collects all of Thek’s letters to Hujar (Thek didn’t save any of Hujar’s letters), and includes Hujar’s photos of Thek throughout their relationship.”

Seized by Joy: Paintings 1965–1988 by Paul Thek is on show at Thomas Dane Gallery in London until 2 August 2025.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImagePeter Hujar, Paul Thek (IV), 1975© 2025 The Peter Hujar Archive / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, DACS London. 2025

In 1975, an image of Paul Thek was captured by his then-lover, downtown New York photographer Peter Hujar. Thek wears a grey marl T-shirt, tight at the arms, positioned in profile against a bare wall. Although the photograph is printed in black and white, his skin looks sun-warmed, weathered. He’s beautiful in a classical way, moustached, angular, sweat on his neck. This is the face of one of the most important artists whom no one remembers.

Hujar and Thek were not true habitués of Andy Warhol’s Factory, but in 1964, they sat for Screen Tests, three-minute cinematic talking-head portraits. Their impassive faces would sometimes appear on the walls at Warhol parties, as part of screening events entitled Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys, testifying to Thek’s beauty.

Born in Brooklyn in 1933, Thek was raised in a Catholic family. Later, he became close to Susan Sontag, who dedicated her first book, Against Interpretation (1966), to him. Thek was one of the most radical contemporary artists to emerge during the 1960s, yet his work has been largely unrecognised for decades. Now, Thek’s paintings are on show at Thomas Dane Gallery in London in a new exhibition, Seized by Joy: Paintings 1965–1988, curated by Kenny Schachter and designer Jonathan Anderson.

Here, Kenny Schachter, Lynne Tillman, Andrew Durbin, Gary Schneider, Jack O’Brien, Fiona Anderson, Tarek Lakhrissi, and Francis Schichtel speak on the lasting legacy of Paul Thek.

Kenny Schachter, Artist, Writer and Curator

“I saw Thek’s Witte de With show in Rotterdam in the mid-90s – The Wonderful World That Almost Was – and I was floored. It was one of the most extraordinary art experiences I’ve ever had, and it’s still so bitterly with me. Those pieces are profound and remain to this day absolutely unprecedented and unparalleled by anything sculpturally that’s come before or after them.

“I’ve been literally coexisting with Paul’s work for more than 30 years. To drive home my point, I took two drawings off the wall from the show, and they’re hanging where I’m staying [in an Airbnb in Spain]. These are beautiful drawings. It’s a two-page self-portrait; he’s in bed, naked. I press my nose up against his work. Some lines are so heavily wrought you can see the lead reflecting where he gouged the surface. Every day, it seizes me with joy. I don’t think a day’s gone by where I haven’t spent a night with Paul Thek, having never met him. And that’s really my love affair.”

Lynne Tillman, Novelist

“The art of Paul Thek, a near-mythical figure, is sui generis. Thek’s brilliant, curious, startling art has rarely been exhibited. This happens to artists who are beyond category; they confound critics, gallerists and collectors. Fortunately, Andrew Durbin’s biography and cultural history of Thek and photographer Peter Hujar will tell the story of their formative years, relationship and aesthetic development. Durbin is doing the important work of excavating Paul Thek’s unique oeuvre.”

“I don’t think a day’s gone by where I haven’t spent a night with Paul Thek, having never met him. And that’s really my love affair” – Kenny Schachter

Andrew Durbin, Author and Editor-in-Chief of Frieze

“In his lifetime, Thek kept more than 125 diaries, in which he copied favourite passages from books, sketched landscapes and lovers and friends and little objects, drafted poems, reflected on his childhood and life, conducted self-interviews, and wrote autofiction. In writing my forthcoming book about Thek and his friend, Peter Hujar, I fell madly in love with Paul’s writing. Lines from his notebooks and letters still return to me as guiding lights.

“Right now, I’m thinking of a phrase from a 1988 painting, one of his last works, made when he was dying: ‘While there’s still time, let’s go out and feel everything.’ Those words capture his attitude as an artist. Keenly aware of the limits placed on any human life, he sought, always, experience. “Reaching out to experience is really so key to joie de vivre,” a friend recently remarked to me after the death of Edmund White, another great lover of life. Thek understood that intuitively, and it guided his work to the very end. His work says, go and live. That is his greatness – and his generosity.”

Gary Schneider, Photographer

“In 1977, when I first visited Peter Hujar’s live/work loft, a large painting hung in the entrance. Paul Thek painted it in 1963 during the height of their romantic relationship. It is a grid composed of 25 fragments of Peter’s face. The Thek painting was included in the Hujar exhibition, Eyes Open in the Dark, that John Douglas Millar and I co-curated at Raven Row in London. I was staying in a flat in the museum and was able to visit the painting every day, which was an emotional experience for me each time. In the painting I had known, the dominant tonality had been an orange, white and muddy black – the accumulation of Peter’s heavy cigarette smoking. The conserved painting has bright whites with inky blacks. I’m grateful that I got to experience it in its original glory.”

Jack O’Brien, Artist

“I still think about the works from Thek’s series Technological Reliquaries – that hand, the pink flesh, the mirrored vitrines. They’re such brutal and devotional objects. He presented a sculptural language that was so lush and so perishable it almost refused to be historicised, but nonetheless, it laid the groundwork for artists like myself. I think about how he staged collapse and camp at the same time, offering a kind of moral choreography for objects, like they were performing their own fragility.

“In my own work, I’ve used impoverished and overly familiar materials – used leather chairs, silver coins, loose cords – trying to tune themselves into something excessive or devotional, but never quite resolved. I think Thek did that with enormous grace. There’s also something in the theatricality – how his installations tilt between ritual and rehearsal – that feels close to me now, especially in thinking about sculpture as stage, prop, or accidental gag.“

Fiona Anderson, Art Historian and Author

“Seeing some of the Technological Reliquaries in person for the first time at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 2010, I was caught off guard by their strange, intermediate size, evoking something between farm animal and human being, and by their tenderness and their humour.

“The small scale of La Corazza di Michelangelo (1963), a cheap souvenir reproduction of an armoured Roman breastplate (bought in Italy with the photographer Peter Hujar) encrusted with lumps of wax and red acrylic paint, moved me in particular. It was compelling, disgusting, and sexy. Thek made this work after visiting the Palermo catacombs with Hujar and, as he famously told the critic Gene Swenson in 1966, picking up what he thought was a piece of paper and finding it crumble in his hand, realised it was a piece of dried thigh. In La Corazza, the boundaries between ancient history and Thek’s present, pain and pleasure, disgust and attraction, self and other, collapse. Thek’s sculptures offer a queer way of thinking about bodies and sculpture in 1960s America. But in their tender humour and sense of play and pleasure, they elude straightforward scholarly analysis, too. As Thek’s friend Susan Sontag argued: ‘In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art’.”

“Thek is less an influence than a companion: someone who opened the door for queer aesthetics to be both wounded and luminous, or bright” – Tarek Lakhrissi

Tarek Lakhrissi, Artist

“Paul Thek’s work resonates deeply with my own practice, especially in how he embraces fragility, spirituality, and the body as sites of resistance and transformation. As a queer artist working across video, sculpture, and poetry, I see in Thek a kind of spiritual predecessor, someone who dared to make the vulnerable sacred. Like Thek, I often draw on language, myth, and ritual to confront dominant narratives and imagine alternative futures. Thek is less an influence than a companion: someone who opened the door for queer aesthetics to be both wounded and luminous, or bright.”

Francis Schichtel, Archivist and Photographer

“I came to Paul Thek through my work at the Peter Hujar Archive where I scanned all of Hujar’s negatives. In a small, windowless storage unit, I spent three years going through each roll shot by Peter. I remember coming across his photos where Thek first appears in 1956, in Coral Gables. The images are tender, curious, and there’s a beauty in the way they explored each other. I followed their travels through Italy, trips to Fire Island, and watched both of their artistic practices evolve. Their powerful relationship is right there in pictures. I was so moved by Thek’s gorgeous face and the way Peter saw him. And there was something in the way I imagined they lived that inspired me.

“I later discovered Thek’s letters to Hujar, and was totally riveted. Their romance, playfulness, charm, and humility were captivating, and it put words to the images and relationship I spent so much time looking at. The letters read like a novel. Paul Thek and Peter Hujar: Stay Away from Nothing will be coming out this autumn, published by Primary Information. It collects all of Thek’s letters to Hujar (Thek didn’t save any of Hujar’s letters), and includes Hujar’s photos of Thek throughout their relationship.”

Seized by Joy: Paintings 1965–1988 by Paul Thek is on show at Thomas Dane Gallery in London until 2 August 2025.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.