Rewrite

“Today those images of sex and drugs are not as impactful, so we chose ones that had a bit more subtlety,” says Larry Clark of his new and updated version of Tulsa

An intimate and harrowing study of the transgressive lifestyle adopted by his own immediate circle of suburban teenagers, Larry Clark’s Tulsa was a shock to the system of picket-fence America when it was released in 1971. “This is not a picture book that will lie quietly and without protest on coffee tables,” observed Dick Cheverton in a review for The Detroit Free Press, published at the time under the moniker A Devastating Portrait of an American Tragedy. “Nor is this book easy to pick up, confront, challenge. For this is a collection of photographs that assail, lacerate, devastate. And ultimately indict.”

“This was not the image of America that people were interested in portraying,” says the controversial photographer and filmmaker over email. “At the time, it was all about selling this idea that everything was like a Norman Rockwell painting. This was what I was witnessing though, and I thought it was important to show a more realistic viewpoint of the world.” Made in 1963, 1968 and 1971, around his move to New York (1964) and subsequent deployment to Vietnam (1964-65), after which he returned to his hometown, the pictures foreground drug abuse and the surrounding culture (mainly guns and sex), of which Clark himself was a part: experimenting with amphetamines at 16, he’d graduated to heroin by the age of 20.

Because of its outlaw-adjacent subjects, the series was difficult to get published until the photographer Ralph Gibson, a friend of Clark’s, stepped in; Danny Seymour, whose own photobook A Loud Song preceded it, footed the bill. “Once we had put out Tulsa, it was flying off the shelves,” recalls Clark. “I think it sold out in maybe two days, something like that. Once that happened, it made sense to keep photographing the things I was interested in, as it seemed others were also interested in seeing those things.”

Indeed, the tone and visceral nature of Tulsa set it far apart from other work of the era, and it would go on to shape a generation of photographers and directors, most notably informing Gus Van Sant’s 1989 film Drugstore Cowboy (later, Van Sant would be credited as an executive producer on Clark’s notorious debut film, Kids).

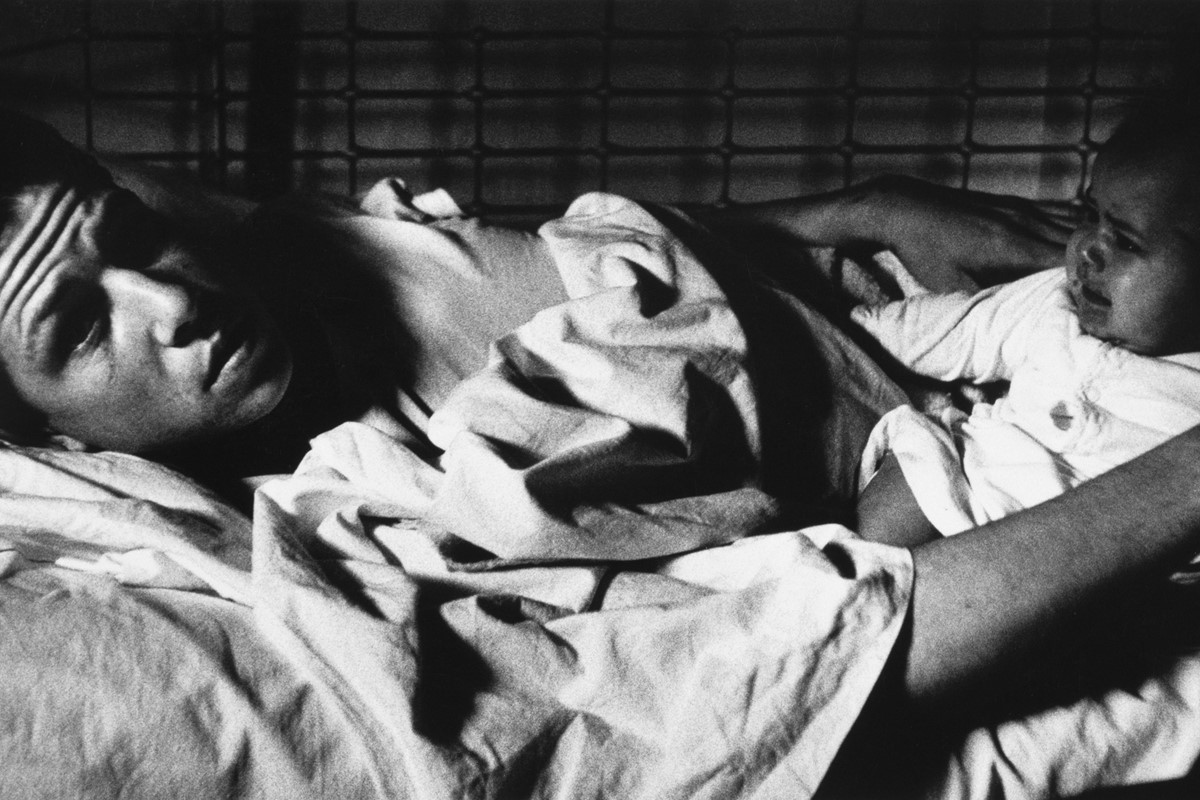

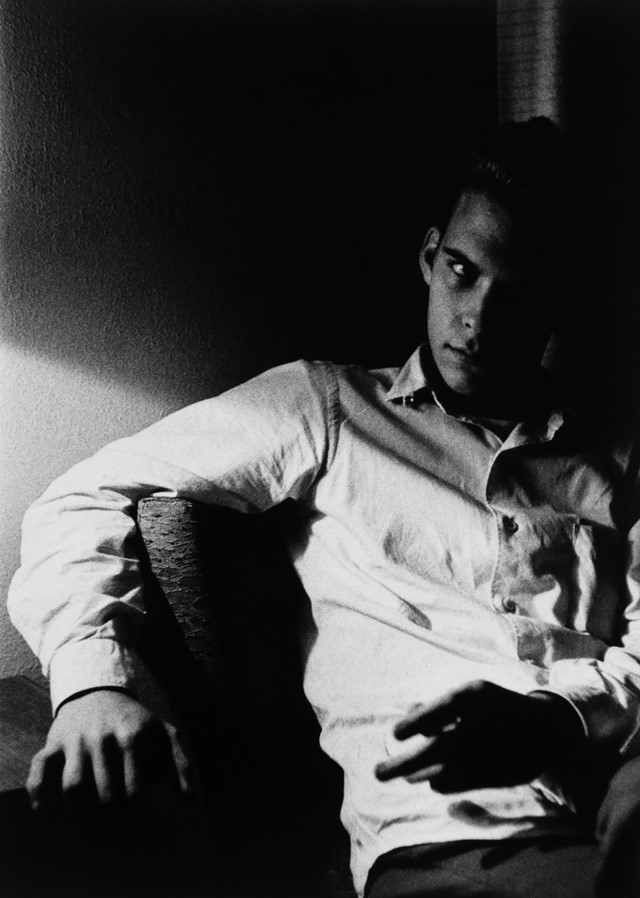

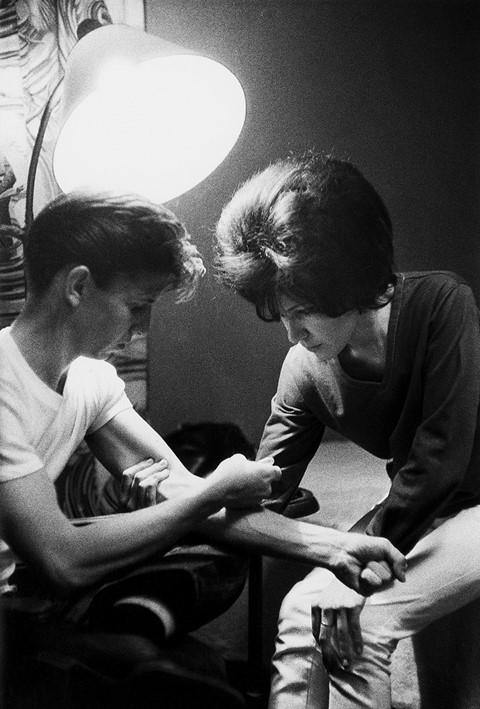

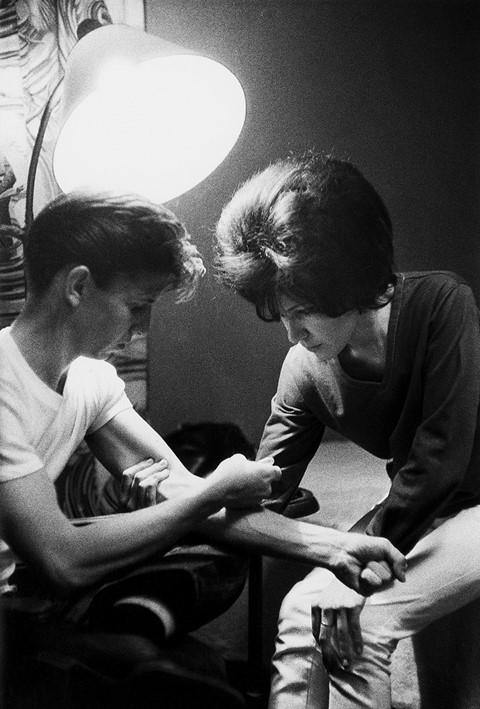

50 years later, Tulsa is now being revisited under a new title – Return – in a new book published by Stanley/Barker. “They wanted to do something with some of my older photographs that hadn’t been seen, so my assistant Zeljko and I selected a delicate and sensual collection,” offers Clark, relaying how the monograph came together. “At the time Tulsa came out, the more over-the-top ones made the most sense, but today those images of sex and drugs are not as impactful, so we chose ones that had a bit more subtlety.” While the claim doesn’t ring false, Return remains explicit nonetheless and sometimes jarring; in contrast to the grainy quality of the images, Clark’s protagonists disrupt preconceptions of heroin addicts, typically dressed in a clean-cut fashion that mirrors the aesthetics of Teruyoshi Hayashida’s Take Ivy. These kids, it suggests, could be anyone.

Similarly discernable is the intimacy afforded by Clark. While his initial entry point into photography was via his mother, a door-to-door baby photographer whom Clark assisted in his mid-teens – a “humiliating” experience, he told the New York Times – with his friends he felt comfortable. “You wouldn’t have been able to take those kinds of pictures if people weren’t okay with it,” he says. “And I always had a camera with me. If I forgot it people would say, ‘Hey Larry, where’s your camera?’ It’s always been important to me to show the way that the world is around me.” Absorbed in the present, the images speak to a particular moment, often tightly cropped, focused on a specific hit or the aftermath. And what of Clark’s subjects today – have they settled down? “Some of my friends were thinking about the future, and partnered up and had kids,” he says. “For me, it wasn’t until I was around 40 that I started to think that way.”

Return by Larry Clark is published by Stanley/Barker, and is out now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

“Today those images of sex and drugs are not as impactful, so we chose ones that had a bit more subtlety,” says Larry Clark of his new and updated version of Tulsa

An intimate and harrowing study of the transgressive lifestyle adopted by his own immediate circle of suburban teenagers, Larry Clark’s Tulsa was a shock to the system of picket-fence America when it was released in 1971. “This is not a picture book that will lie quietly and without protest on coffee tables,” observed Dick Cheverton in a review for The Detroit Free Press, published at the time under the moniker A Devastating Portrait of an American Tragedy. “Nor is this book easy to pick up, confront, challenge. For this is a collection of photographs that assail, lacerate, devastate. And ultimately indict.”

“This was not the image of America that people were interested in portraying,” says the controversial photographer and filmmaker over email. “At the time, it was all about selling this idea that everything was like a Norman Rockwell painting. This was what I was witnessing though, and I thought it was important to show a more realistic viewpoint of the world.” Made in 1963, 1968 and 1971, around his move to New York (1964) and subsequent deployment to Vietnam (1964-65), after which he returned to his hometown, the pictures foreground drug abuse and the surrounding culture (mainly guns and sex), of which Clark himself was a part: experimenting with amphetamines at 16, he’d graduated to heroin by the age of 20.

Because of its outlaw-adjacent subjects, the series was difficult to get published until the photographer Ralph Gibson, a friend of Clark’s, stepped in; Danny Seymour, whose own photobook A Loud Song preceded it, footed the bill. “Once we had put out Tulsa, it was flying off the shelves,” recalls Clark. “I think it sold out in maybe two days, something like that. Once that happened, it made sense to keep photographing the things I was interested in, as it seemed others were also interested in seeing those things.”

Indeed, the tone and visceral nature of Tulsa set it far apart from other work of the era, and it would go on to shape a generation of photographers and directors, most notably informing Gus Van Sant’s 1989 film Drugstore Cowboy (later, Van Sant would be credited as an executive producer on Clark’s notorious debut film, Kids).

50 years later, Tulsa is now being revisited under a new title – Return – in a new book published by Stanley/Barker. “They wanted to do something with some of my older photographs that hadn’t been seen, so my assistant Zeljko and I selected a delicate and sensual collection,” offers Clark, relaying how the monograph came together. “At the time Tulsa came out, the more over-the-top ones made the most sense, but today those images of sex and drugs are not as impactful, so we chose ones that had a bit more subtlety.” While the claim doesn’t ring false, Return remains explicit nonetheless and sometimes jarring; in contrast to the grainy quality of the images, Clark’s protagonists disrupt preconceptions of heroin addicts, typically dressed in a clean-cut fashion that mirrors the aesthetics of Teruyoshi Hayashida’s Take Ivy. These kids, it suggests, could be anyone.

Similarly discernable is the intimacy afforded by Clark. While his initial entry point into photography was via his mother, a door-to-door baby photographer whom Clark assisted in his mid-teens – a “humiliating” experience, he told the New York Times – with his friends he felt comfortable. “You wouldn’t have been able to take those kinds of pictures if people weren’t okay with it,” he says. “And I always had a camera with me. If I forgot it people would say, ‘Hey Larry, where’s your camera?’ It’s always been important to me to show the way that the world is around me.” Absorbed in the present, the images speak to a particular moment, often tightly cropped, focused on a specific hit or the aftermath. And what of Clark’s subjects today – have they settled down? “Some of my friends were thinking about the future, and partnered up and had kids,” he says. “For me, it wasn’t until I was around 40 that I started to think that way.”

Return by Larry Clark is published by Stanley/Barker, and is out now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.