Rewrite

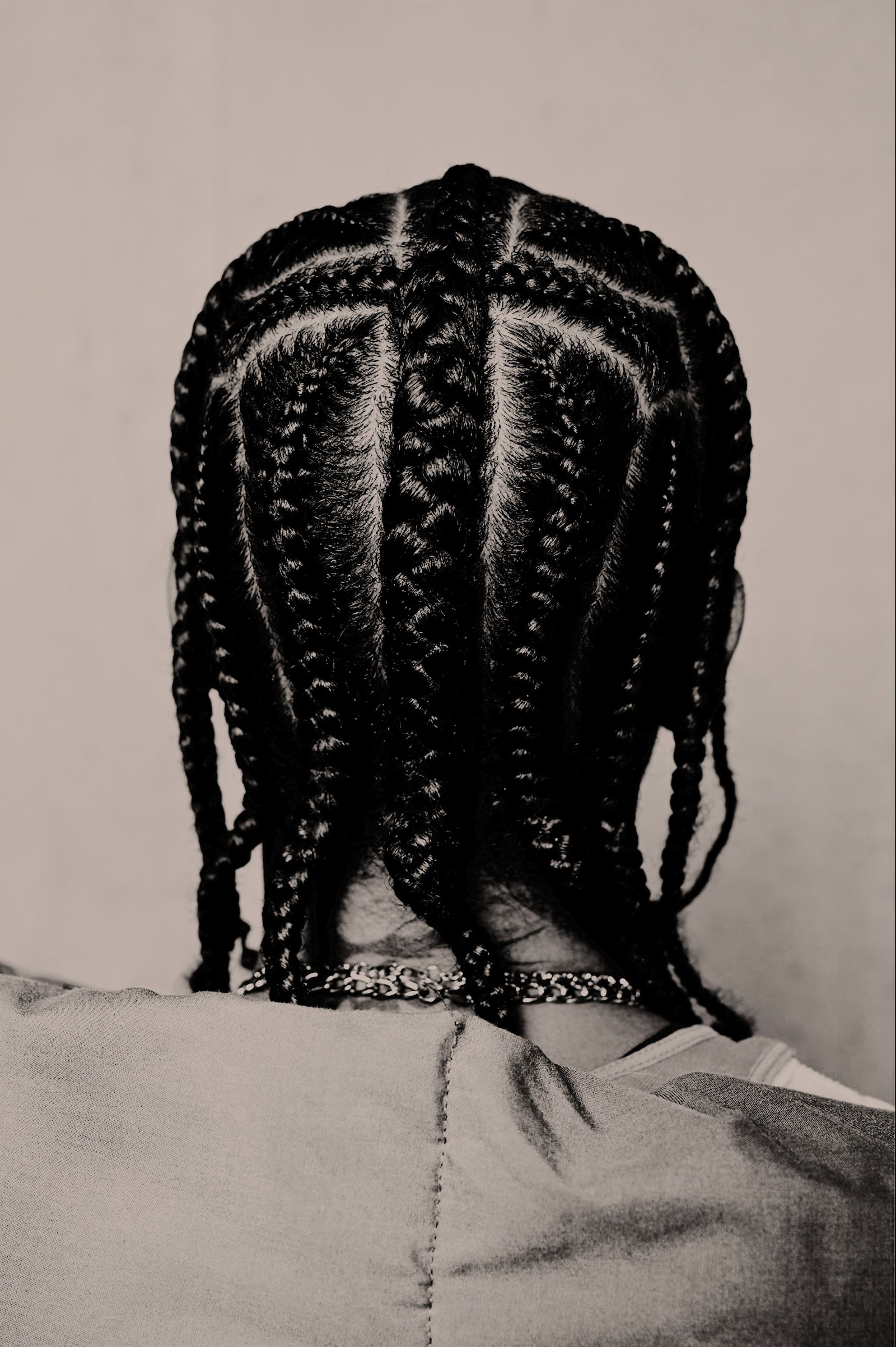

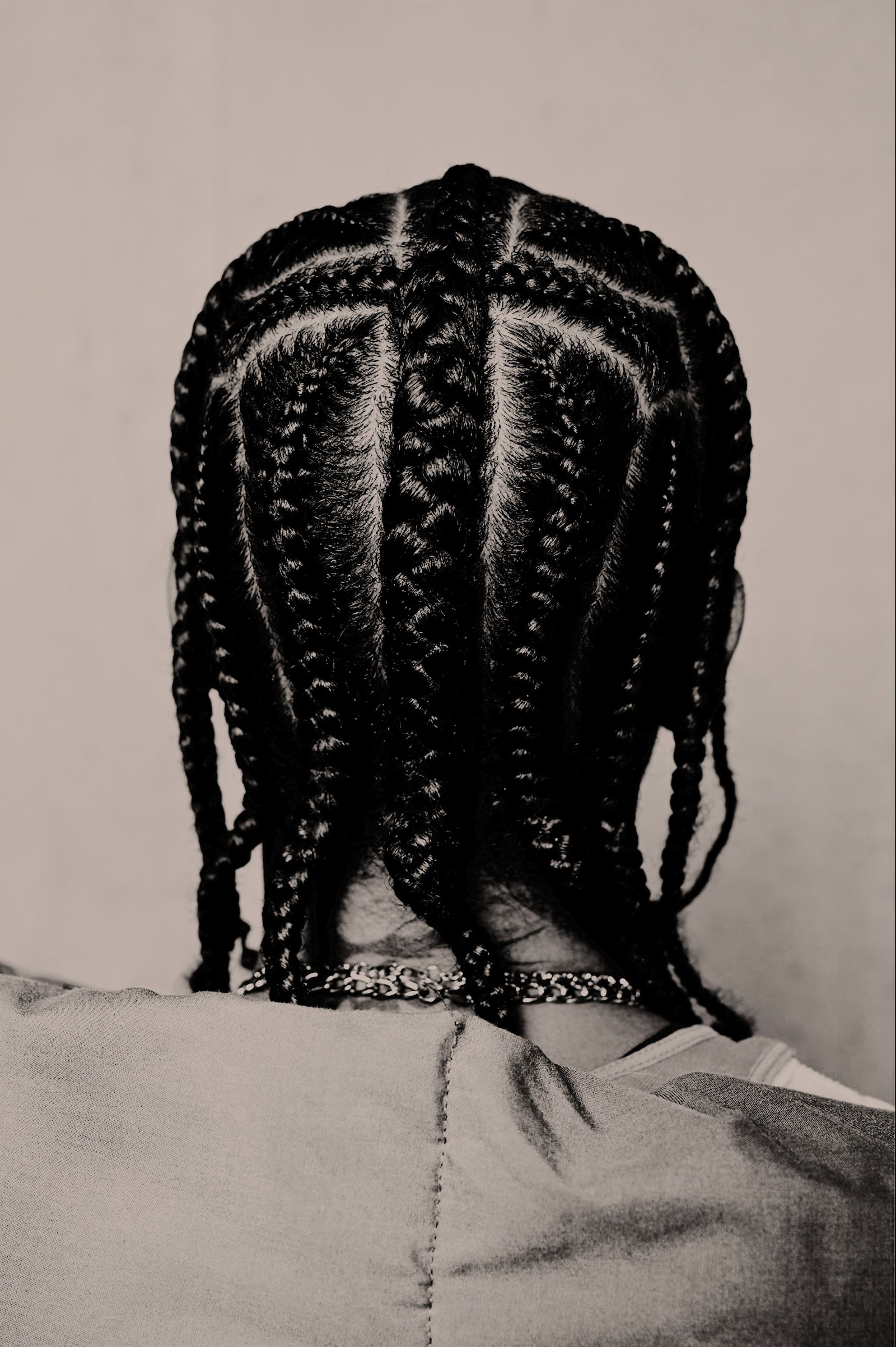

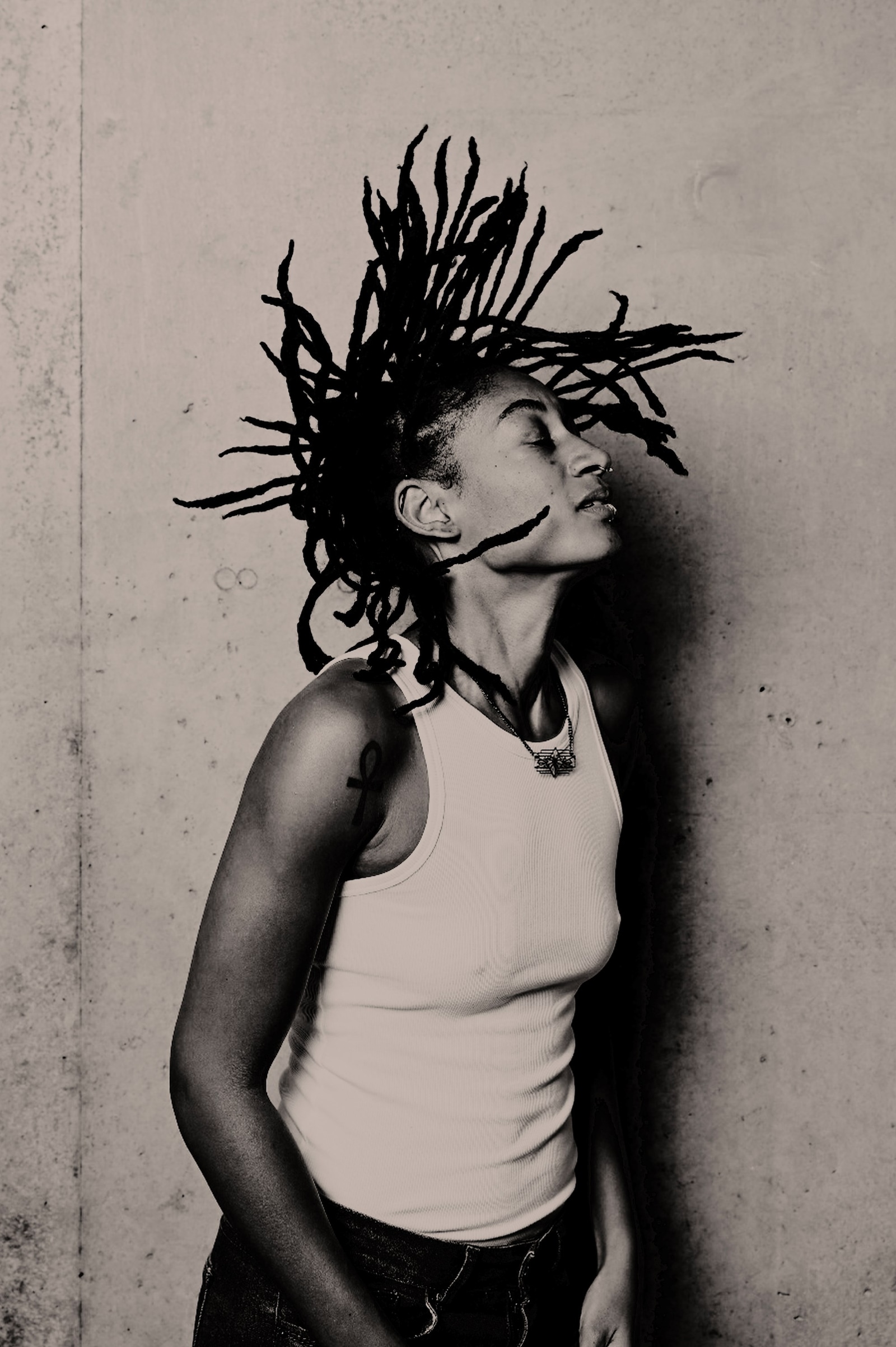

Lead ImagePhotography by Késsia Riany, Tauana Sofia, Pedro Henrique. Styling by Stella Nunes

As Central Saint Martins’ MA Fashion Communication course celebrates a decade of talent with a debut publication, which follows a public exhibition at Granary Square, Rethinking Fashion Image, a clear thread emerges among this year’s graduates. “Fashion image makers on our MA often treat the word ‘fashion’ rather loosely. We encourage that,” says course leader Roger Tredre. “For the tenth anniversary of the course, we brought together the best of this year’s work into our own magazine, with the subtitle How We Feel Now. It reflects the power and immediacy of photography in conveying emotions.”

Across its pages, six artists explore the subtleties of contemporary identity with striking intimacy. “Although quite different in style and created in locations around the world, each project is very much rooted in the personal experience of each image maker,” adds fashion image course leader Adam Murray.

Below, find out more about the projects created by these photographers, stylists and art directors.

For Yongjie Hu, capturing the beauty of an intimate relationship is a way to testify honestly to his emotions and to his evolving place in the world. There is no sense of ceremony in his approach: the Chinese photographer is driven by a desire to preserve the reality of moments he never wants to forget.

Working with 120 and 135 format film cameras, Hu weaves together spontaneous snapshots and carefully staged self-portraits, often placing himself and his boyfriend within the same frame. “These photographs resemble less commemorative portraits and more an act of deliberate contemplation: placing our relationship upon a stage, replicating it, confronting it, scrutinising it, and tenderly embracing it,” Hu explains.

Through his work, Hu explores emotional relationships as a fluid form, embracing the fluidity and vulnerability that come with intimacy. His images become an imprint of time itself. “Each time I press the shutter, it feels like telling my present self: ‘Even if all this will change, it truly existed in this moment.’” By acknowledging these emotional fluctuations, he restores their legitimacy: even if the feeling fades tomorrow, it was real.

Jordy Nasa crafts images the way musicians shape sound: through rhythm, intuition and a language that speaks without words. An art director and stylist from Atlanta, they operate between fine art and fashion photography, treating clothing and composition as instruments of storytelling.

Nasa’s work turns to the writings of Frantz Fanon, pulling apart the mechanisms of the white gaze and its fractured vision of Black identity in America. Shaped by their moves between Huntsville, Atlanta, and New York, they reconstruct these ideas visually, reclaiming the Black gaze through themes of diaspora, ego, duality, the shifting terrain of the self, and the constant negotiation of belonging.

Nasa returns to Atlanta with a renewed gaze. “Atlanta still has something to say. Living in Europe now, I realised that there was an opportunity to display a more diverse and intimate representation that people may not have been exposed to,” they say. Shot by Kourtney Iman and Xavier Thompson in their hometown, the result is a portrait of Atlanta shaped by love and memory, capturing its people in a state of pure authenticity.

Pacor Wang is the ultimate street style anthropologist. The Shanghai-native photographer navigates the visual landscape with a documentary gaze, treating the camera as a tool to bridge the split between the curated and the candid. “I like observing how people behave in natural, unposed states. These moments inspire me to bring a sense of authenticity and contemporaneity into my work,” he says.

Wang’s practice operates in that tricky space where reality and virtuality intersect. He rejects the idea that fashion imagery must be hyper-polished, drawing instead from the “unconscious seeing” of daily life. That could be the posture of a commuter on the tube or the stillness of a stranger in a park.

For his recent project, Wang turned this observational lens toward the diverse youth community of Hackney, the borough he has called home since September. Recognising it as one of London’s most vital cultural arteries, he sought to document the palpable sense of community that pulses through its streets – from the green expanses of London Fields and Victoria Park to the dynamism of Hackney Wick and the tranquil life along the River Lea.

Besides camera duties, Wang focused on connecting with individuals who embody the specific spirit and energy of the neighbourhood. This approach merges the everyday moments observed in his research with his photography, capturing a vital sense of connection between these young people and their environment. “What fascinated me was the atmosphere,” he says. “You can even see the ‘creatures’ of the area appearing in my frames – small birds and wild cats – all of which together shape the diverse and vibrant cultural and artistic landscape of Hackney.”

Stella Nunes admits she is a bit of a voyeur. Born in São Paulo, Brazil, the stylist and art director grew up in a sensory haze of turpentine and cigarette smoke in her father’s painting studio, learning early on how to look at the world before learning how to dress it. “My process is about mixing the intellectual references from art with the sensory experiences of the world,” Nunes says. “Textures, colours, sounds and feelings often become the start of an image for me.”

Her latest project, titled Risco, is a visual rebellion against the tropical caricature often plastered over Latin America. Nunes is interested in the concrete reality of São Paulo, a city she likens to the grey intensity of London or New York. To get there, she opened up her personal archive: a collection of chrome wheels, low-rider decals and garage doors she’s been obsessively cataloguing since 2019.

She takes these symbols of masculine noise and spectacle (along with carnival-inspired fantasy) and strips them of their volume. It’s a specific kind of alchemy; one that mixes the grit of automotive paint with a stillness that feels intimate and strongly feminine. “The project also became a reflection on female existence, probably my own,” she says. “The images sit somewhere melancholic and serene. There is a quiet interplay between vivid cultural references and still, distant bodies that shapes the tone I am always searching for.”

Where does one belong when their history resides in two places? This is the aesthetic territory claimed by Kaine Harrys. Born in Udine, Italy, to Nigerian parents and now orbiting between London and Milan, the self-taught photographer builds images that feel both hushed and intensely charged.

Much of Harrys’ recent work circles around migration as both a movement and a condition, returning to that liminal zone where the body is moving through time and space, uncertain of its anchor. “I know the feeling of carrying one’s past while leaning toward another future,” he says. “That rhythm shaped my parents’ arrival in Italy in the 90s and continues to echo across borders today, living on wherever people are forced to begin again.”

It’s this sensibility that underpins 900 (Novecento), his major project at Central Saint Martins, photographed between Milan and the volcanic terrain of Stromboli. The series looks at Italian identity through the lens of the Black body – not as an outsider peering in, but as an author claiming space within the country’s visual memory. Controlled yet emotionally loaded, the images from 900 are what he calls “quiet but intentional,” stripped to their essentials and anchored in posture, negative space and the faint hum of tension. “I think of them as both documents and propositions,” he says. “[They’re] rooted in reality yet in dialogue with fantasy and memory.”

Do screens inspire us, or do they alienate us? Before joining Central Saint Martins, Lorane Hochstatter had idealised her new London life, carried by the dream of England shaped by visual culture. “The Skins-like life I had imagined didn’t happen,” she says. Confronted with the dissonance between fantasy and experience, she turned to photography, yet another screen, to explore her inner world and personal insecurity.

The Swiss photographer restages fragments of her own life: familiar London streets, intimate interiors, and quintessentially English details, often alongside her friends. By suspending these moments, almost as if in a state of dissociation, Hochstatter creates an in-between space where the desire to escape reality through images ultimately becomes a trap. “Screens don’t just reflect; they build. They overlay new worlds on top of your own, blurring the boundary until the two collapse.”

Her work interrogates the nature of the gaze: obsessive, voyeuristic, constructed through screens. These reassuring yet hollow false realities lull us into fantasising about a better life, while leaving us unprepared for the solitude and uncertainty of the present.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImagePhotography by Késsia Riany, Tauana Sofia, Pedro Henrique. Styling by Stella Nunes

As Central Saint Martins’ MA Fashion Communication course celebrates a decade of talent with a debut publication, which follows a public exhibition at Granary Square, Rethinking Fashion Image, a clear thread emerges among this year’s graduates. “Fashion image makers on our MA often treat the word ‘fashion’ rather loosely. We encourage that,” says course leader Roger Tredre. “For the tenth anniversary of the course, we brought together the best of this year’s work into our own magazine, with the subtitle How We Feel Now. It reflects the power and immediacy of photography in conveying emotions.”

Across its pages, six artists explore the subtleties of contemporary identity with striking intimacy. “Although quite different in style and created in locations around the world, each project is very much rooted in the personal experience of each image maker,” adds fashion image course leader Adam Murray.

Below, find out more about the projects created by these photographers, stylists and art directors.

For Yongjie Hu, capturing the beauty of an intimate relationship is a way to testify honestly to his emotions and to his evolving place in the world. There is no sense of ceremony in his approach: the Chinese photographer is driven by a desire to preserve the reality of moments he never wants to forget.

Working with 120 and 135 format film cameras, Hu weaves together spontaneous snapshots and carefully staged self-portraits, often placing himself and his boyfriend within the same frame. “These photographs resemble less commemorative portraits and more an act of deliberate contemplation: placing our relationship upon a stage, replicating it, confronting it, scrutinising it, and tenderly embracing it,” Hu explains.

Through his work, Hu explores emotional relationships as a fluid form, embracing the fluidity and vulnerability that come with intimacy. His images become an imprint of time itself. “Each time I press the shutter, it feels like telling my present self: ‘Even if all this will change, it truly existed in this moment.’” By acknowledging these emotional fluctuations, he restores their legitimacy: even if the feeling fades tomorrow, it was real.

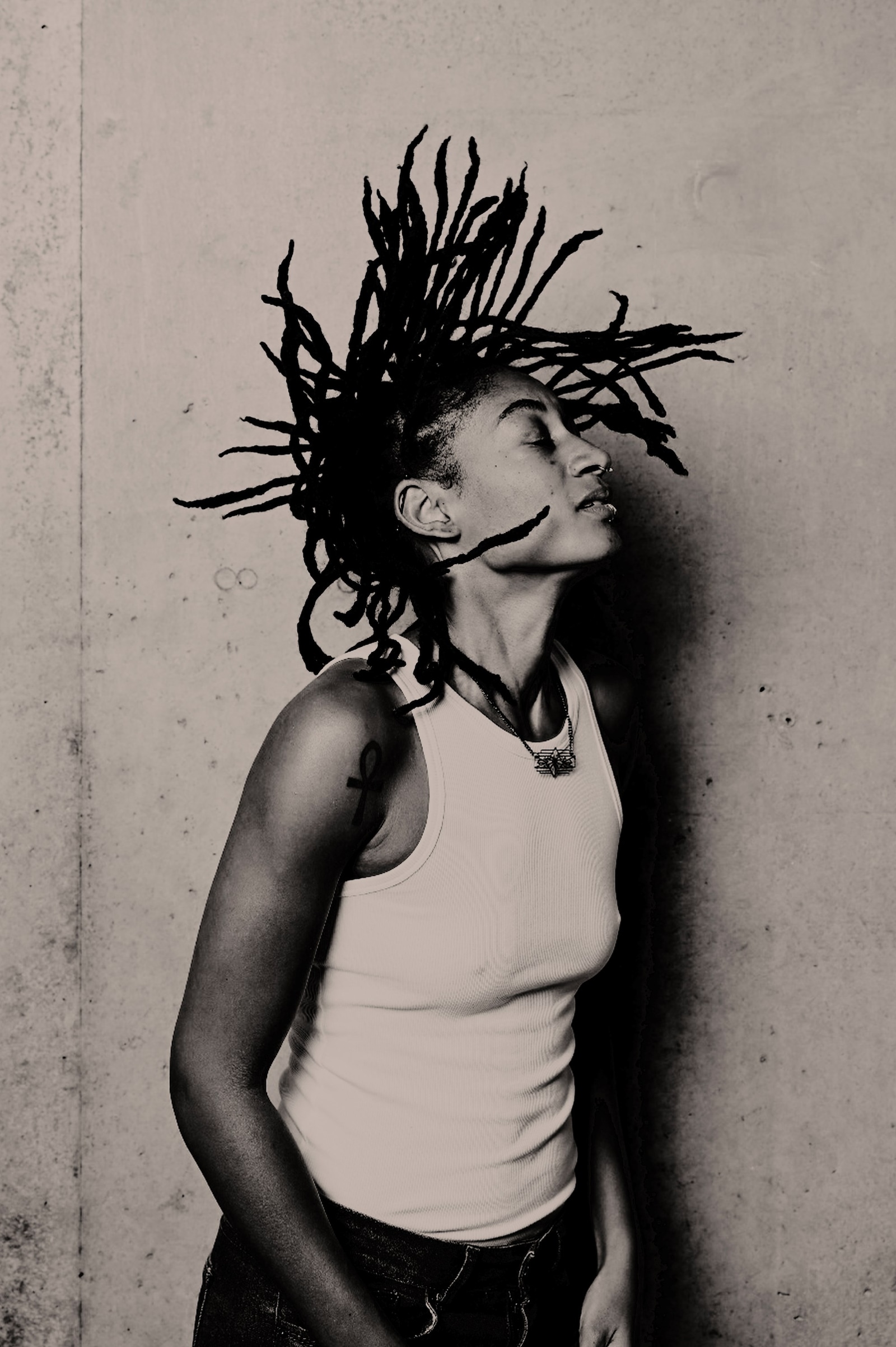

Jordy Nasa crafts images the way musicians shape sound: through rhythm, intuition and a language that speaks without words. An art director and stylist from Atlanta, they operate between fine art and fashion photography, treating clothing and composition as instruments of storytelling.

Nasa’s work turns to the writings of Frantz Fanon, pulling apart the mechanisms of the white gaze and its fractured vision of Black identity in America. Shaped by their moves between Huntsville, Atlanta, and New York, they reconstruct these ideas visually, reclaiming the Black gaze through themes of diaspora, ego, duality, the shifting terrain of the self, and the constant negotiation of belonging.

Nasa returns to Atlanta with a renewed gaze. “Atlanta still has something to say. Living in Europe now, I realised that there was an opportunity to display a more diverse and intimate representation that people may not have been exposed to,” they say. Shot by Kourtney Iman and Xavier Thompson in their hometown, the result is a portrait of Atlanta shaped by love and memory, capturing its people in a state of pure authenticity.

Pacor Wang is the ultimate street style anthropologist. The Shanghai-native photographer navigates the visual landscape with a documentary gaze, treating the camera as a tool to bridge the split between the curated and the candid. “I like observing how people behave in natural, unposed states. These moments inspire me to bring a sense of authenticity and contemporaneity into my work,” he says.

Wang’s practice operates in that tricky space where reality and virtuality intersect. He rejects the idea that fashion imagery must be hyper-polished, drawing instead from the “unconscious seeing” of daily life. That could be the posture of a commuter on the tube or the stillness of a stranger in a park.

For his recent project, Wang turned this observational lens toward the diverse youth community of Hackney, the borough he has called home since September. Recognising it as one of London’s most vital cultural arteries, he sought to document the palpable sense of community that pulses through its streets – from the green expanses of London Fields and Victoria Park to the dynamism of Hackney Wick and the tranquil life along the River Lea.

Besides camera duties, Wang focused on connecting with individuals who embody the specific spirit and energy of the neighbourhood. This approach merges the everyday moments observed in his research with his photography, capturing a vital sense of connection between these young people and their environment. “What fascinated me was the atmosphere,” he says. “You can even see the ‘creatures’ of the area appearing in my frames – small birds and wild cats – all of which together shape the diverse and vibrant cultural and artistic landscape of Hackney.”

Stella Nunes admits she is a bit of a voyeur. Born in São Paulo, Brazil, the stylist and art director grew up in a sensory haze of turpentine and cigarette smoke in her father’s painting studio, learning early on how to look at the world before learning how to dress it. “My process is about mixing the intellectual references from art with the sensory experiences of the world,” Nunes says. “Textures, colours, sounds and feelings often become the start of an image for me.”

Her latest project, titled Risco, is a visual rebellion against the tropical caricature often plastered over Latin America. Nunes is interested in the concrete reality of São Paulo, a city she likens to the grey intensity of London or New York. To get there, she opened up her personal archive: a collection of chrome wheels, low-rider decals and garage doors she’s been obsessively cataloguing since 2019.

She takes these symbols of masculine noise and spectacle (along with carnival-inspired fantasy) and strips them of their volume. It’s a specific kind of alchemy; one that mixes the grit of automotive paint with a stillness that feels intimate and strongly feminine. “The project also became a reflection on female existence, probably my own,” she says. “The images sit somewhere melancholic and serene. There is a quiet interplay between vivid cultural references and still, distant bodies that shapes the tone I am always searching for.”

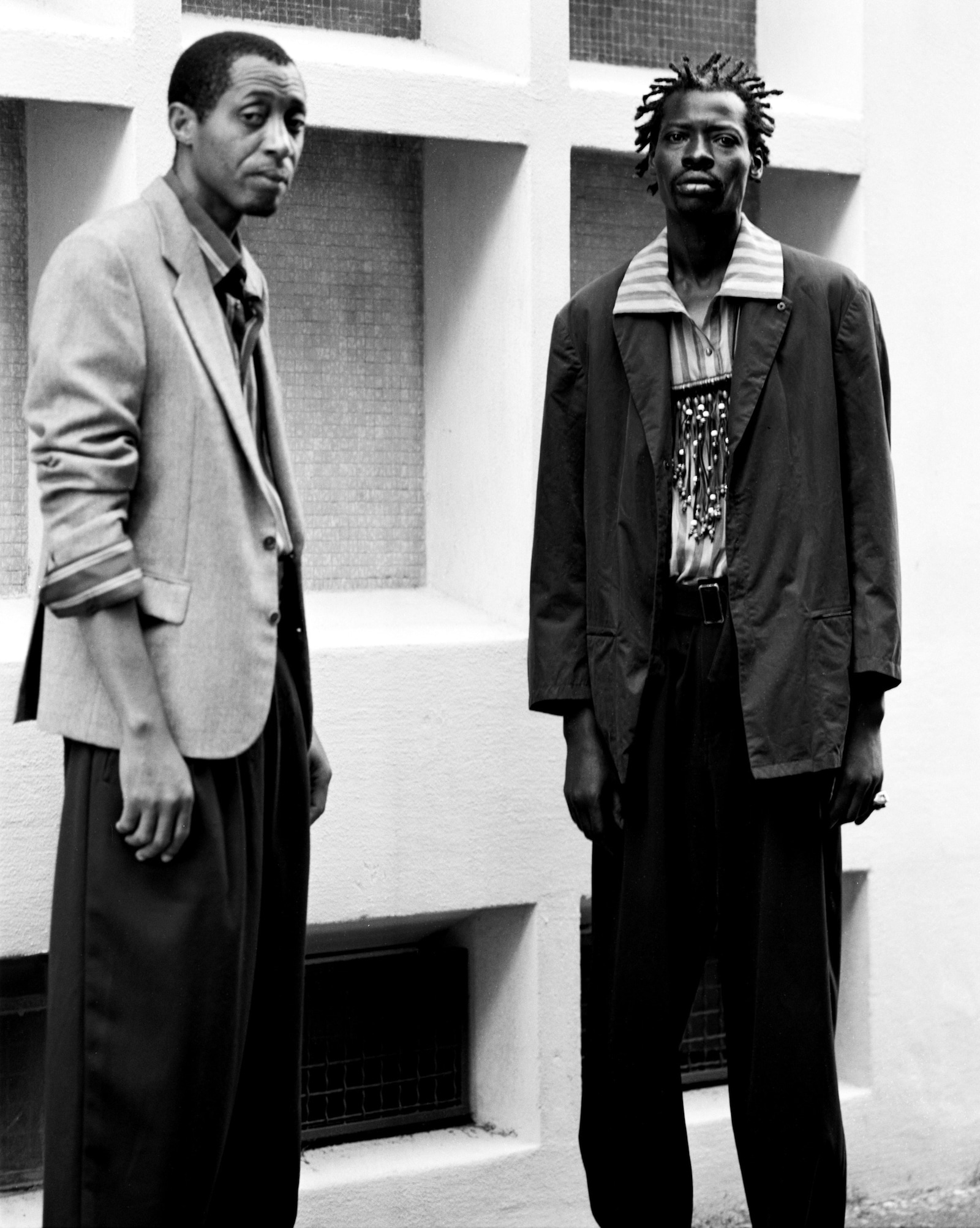

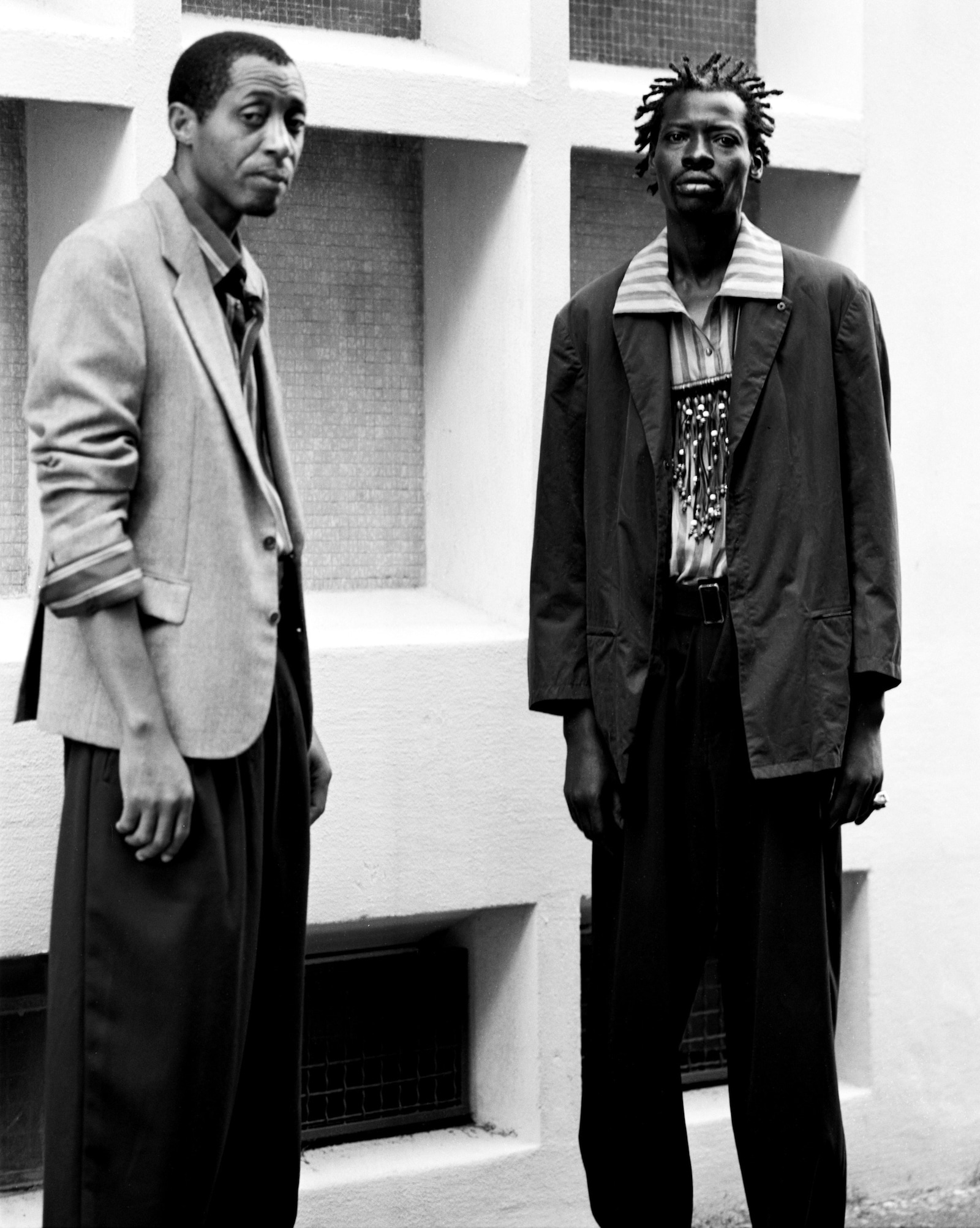

Where does one belong when their history resides in two places? This is the aesthetic territory claimed by Kaine Harrys. Born in Udine, Italy, to Nigerian parents and now orbiting between London and Milan, the self-taught photographer builds images that feel both hushed and intensely charged.

Much of Harrys’ recent work circles around migration as both a movement and a condition, returning to that liminal zone where the body is moving through time and space, uncertain of its anchor. “I know the feeling of carrying one’s past while leaning toward another future,” he says. “That rhythm shaped my parents’ arrival in Italy in the 90s and continues to echo across borders today, living on wherever people are forced to begin again.”

It’s this sensibility that underpins 900 (Novecento), his major project at Central Saint Martins, photographed between Milan and the volcanic terrain of Stromboli. The series looks at Italian identity through the lens of the Black body – not as an outsider peering in, but as an author claiming space within the country’s visual memory. Controlled yet emotionally loaded, the images from 900 are what he calls “quiet but intentional,” stripped to their essentials and anchored in posture, negative space and the faint hum of tension. “I think of them as both documents and propositions,” he says. “[They’re] rooted in reality yet in dialogue with fantasy and memory.”

Do screens inspire us, or do they alienate us? Before joining Central Saint Martins, Lorane Hochstatter had idealised her new London life, carried by the dream of England shaped by visual culture. “The Skins-like life I had imagined didn’t happen,” she says. Confronted with the dissonance between fantasy and experience, she turned to photography, yet another screen, to explore her inner world and personal insecurity.

The Swiss photographer restages fragments of her own life: familiar London streets, intimate interiors, and quintessentially English details, often alongside her friends. By suspending these moments, almost as if in a state of dissociation, Hochstatter creates an in-between space where the desire to escape reality through images ultimately becomes a trap. “Screens don’t just reflect; they build. They overlay new worlds on top of your own, blurring the boundary until the two collapse.”

Her work interrogates the nature of the gaze: obsessive, voyeuristic, constructed through screens. These reassuring yet hollow false realities lull us into fantasising about a better life, while leaving us unprepared for the solitude and uncertainty of the present.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.