Rewrite

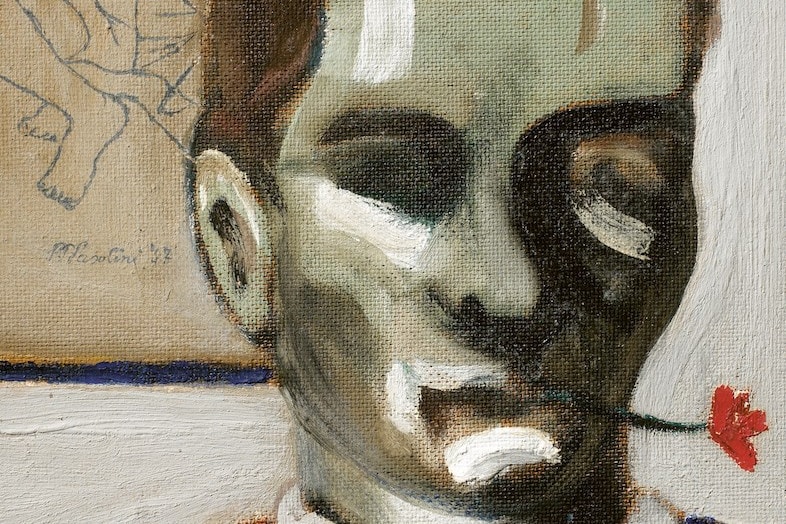

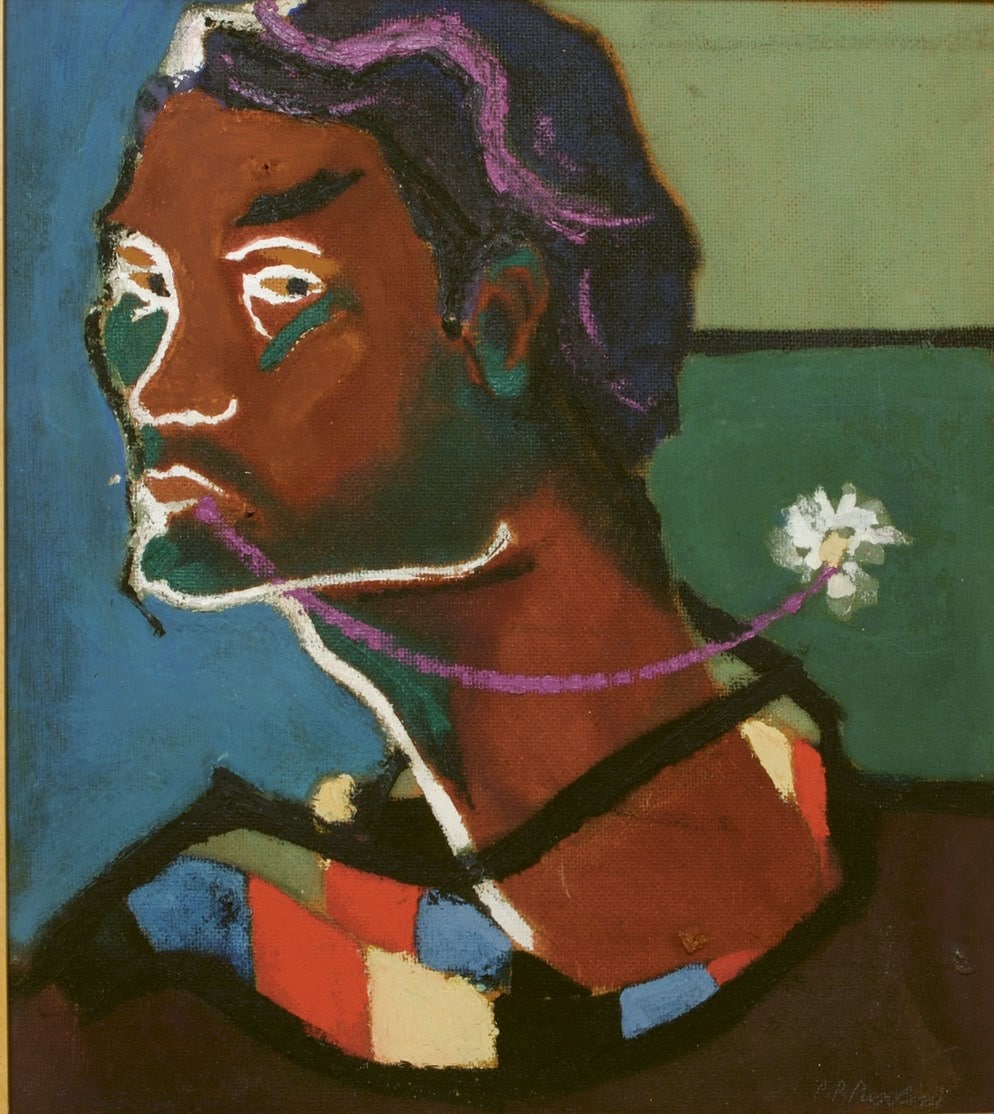

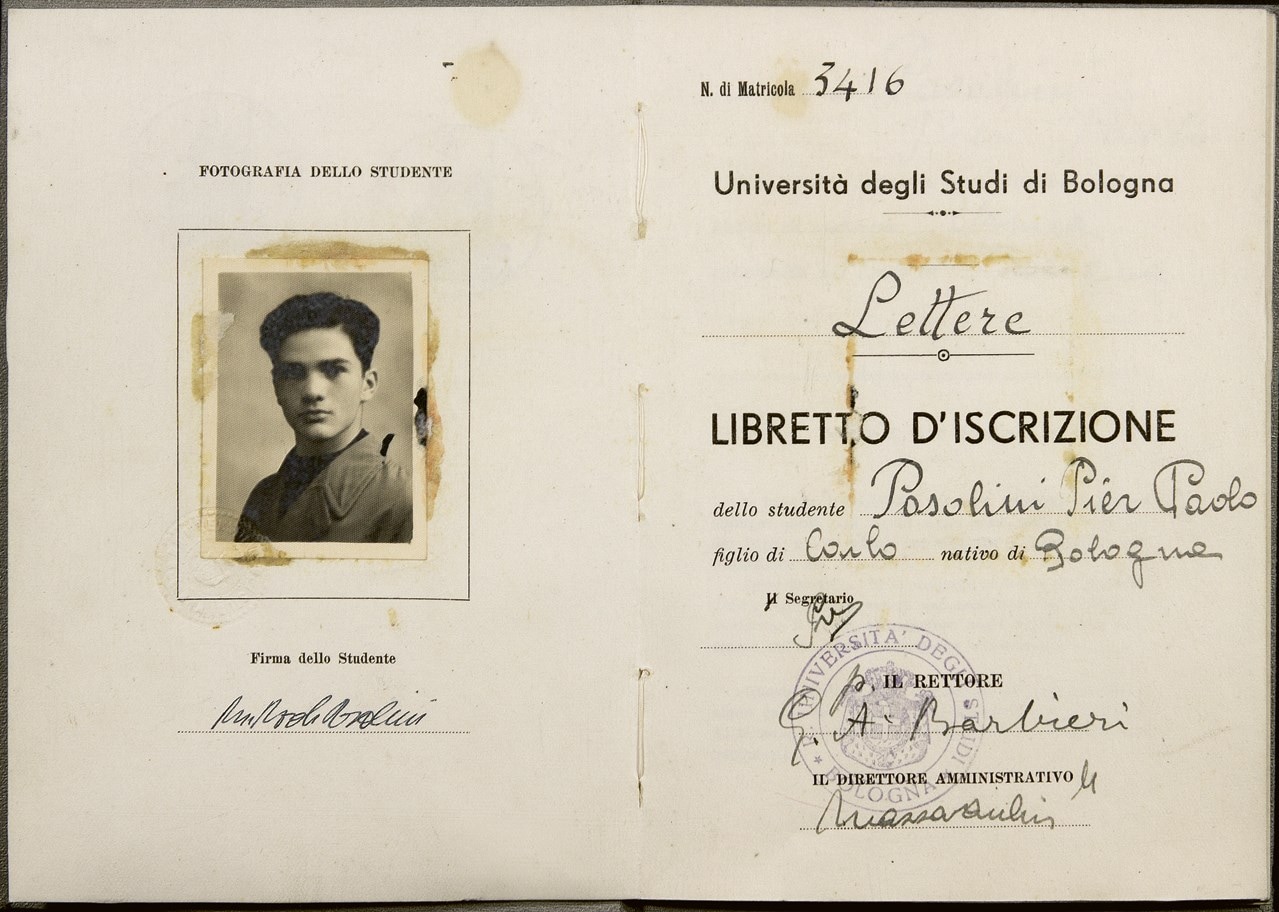

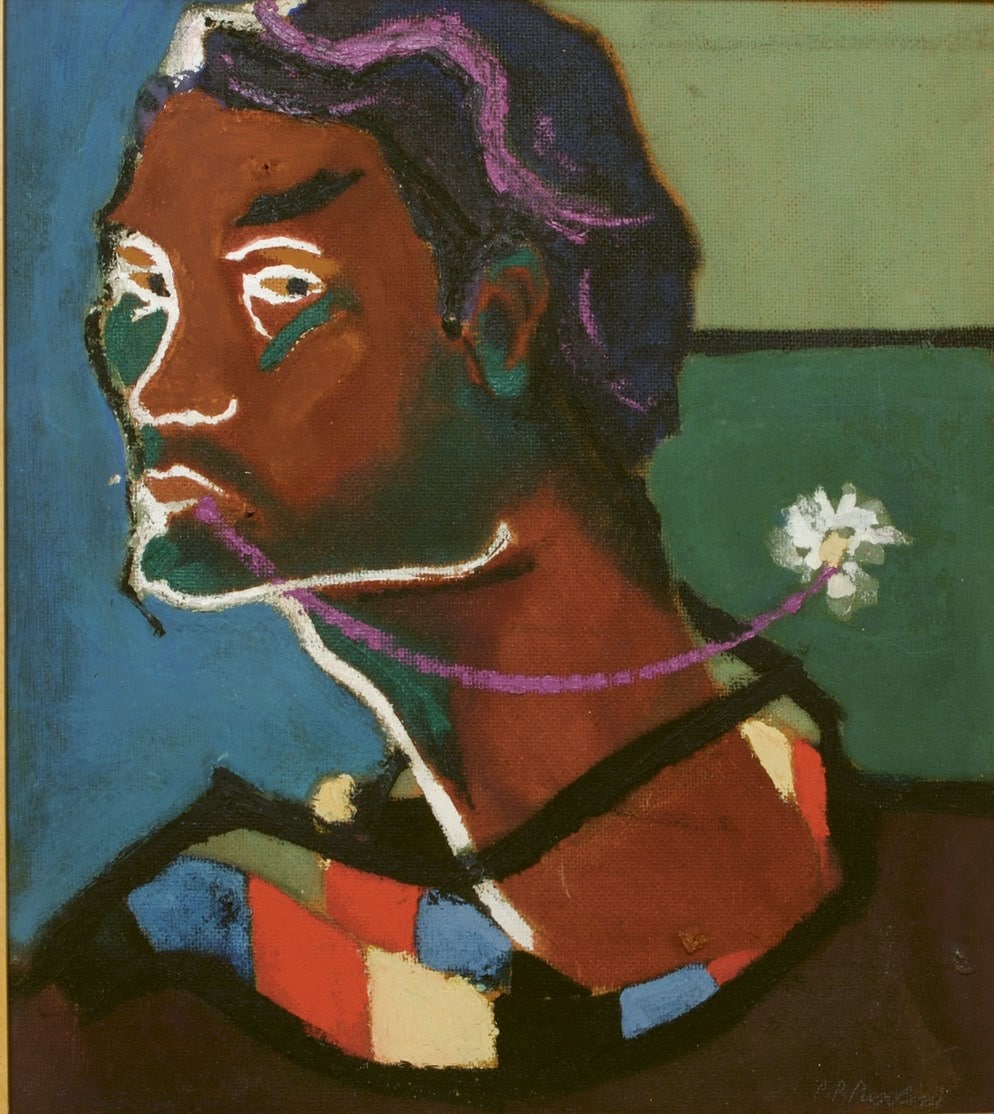

Lead ImagePier Paolo Pasolini, Autoritratto col fiore in bocca (Self-portrait with a flower in her mouth), oil on hardboard, 1947Florence Pasolini archive material courtesy of Archivio Contemporaneo Vieusseux and Graziella Chiarcossi

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale now. Order here.

目次

- 1 Olivia Laing, author

- 2 John Alexander Skelton, fashion designer

- 3 Bruce LaBruce, photographer and filmmaker

- 4 These New Puritans (Jack Barnett), musician

- 5 Eileen Myles, writer and poet

- 6 Colleen Kelsey, film journalist

- 7 Durga Chew-Bose, writer and filmmaker

- 8 Willem Dafoe, actor

- 9 Olivia Laing, author

- 10 John Alexander Skelton, fashion designer

- 11 Bruce LaBruce, photographer and filmmaker

- 12 These New Puritans (Jack Barnett), musician

- 13 Eileen Myles, writer and poet

- 14 Colleen Kelsey, film journalist

- 15 Durga Chew-Bose, writer and filmmaker

- 16 Willem Dafoe, actor

Olivia Laing, author

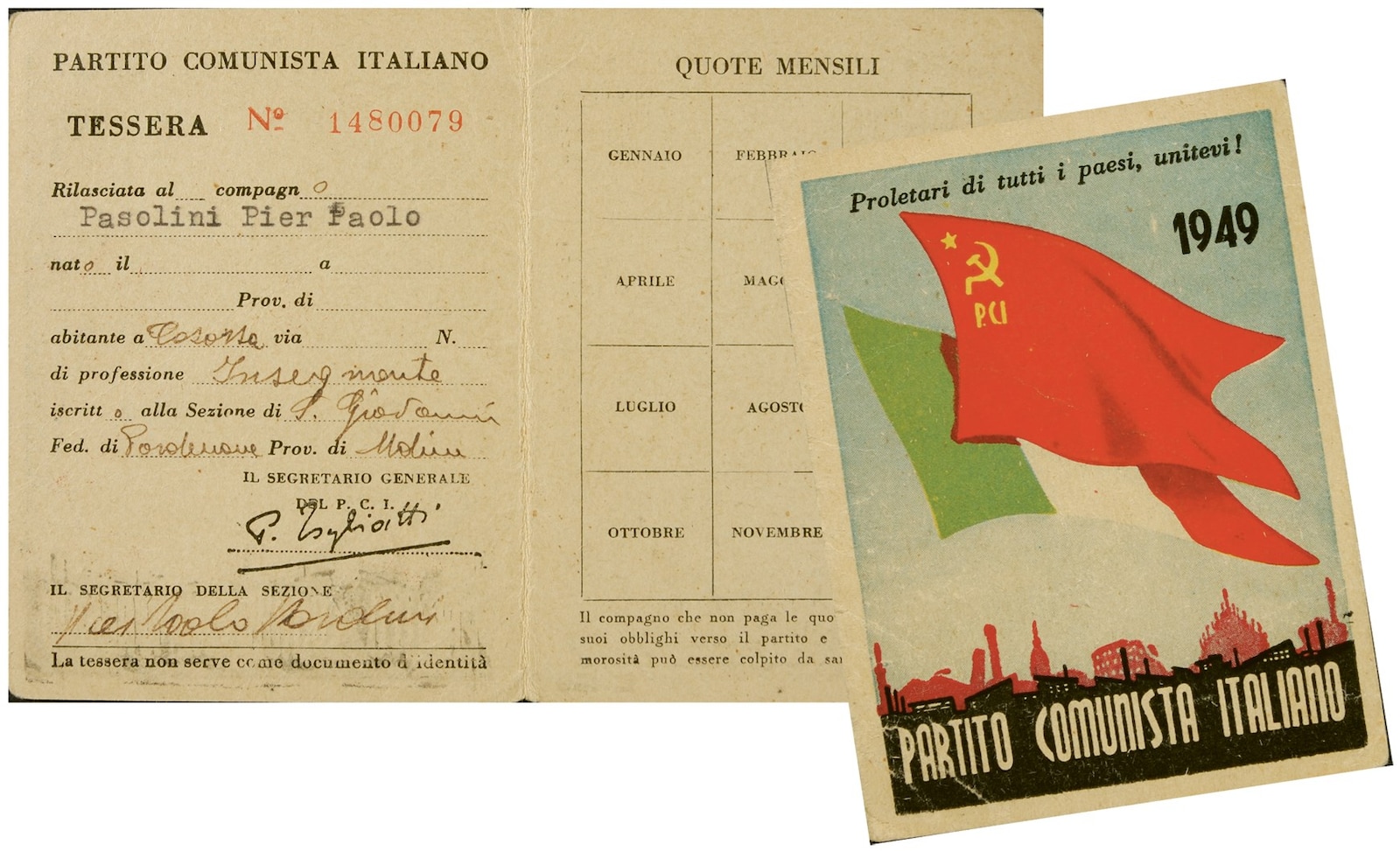

Pier Paolo Pasolini: prophet. He saw what was coming, and Salò, that apocalyptic masterpiece, was his final warning. Almost his last recorded sentence, a few hours before his brutal murder, was “we are all in danger”, siamo tutti in pericolo. Wasn’t he right about that? He warned that capitalism was the new fascism, he dared to say that fireflies were worth more than the industrialisation that was poisoning the Italy he loved. He was a knot of complexities that do not resolve into easy slogans. He inhabited a night-world and left behind him a trail of irreconcilable visions, unlike anything else in cinema. When I wrote The Silver Book (which comes out on November 6 via Penguin), I wanted him to be a mystery even to his closest friends: driven, enigmatic, unknowable, gentle, always working, always alone. I read somewhere that nobody cared about his murder, but the record shows the opposite. The whole vast space of Campo de’ Fiori was packed for his funeral. The street boys he championed, fucked, befriended, placed at the centre of the story: they all came out for him and when the coffin was carried through the crowd, they raised their fists in valediction.

John Alexander Skelton, fashion designer

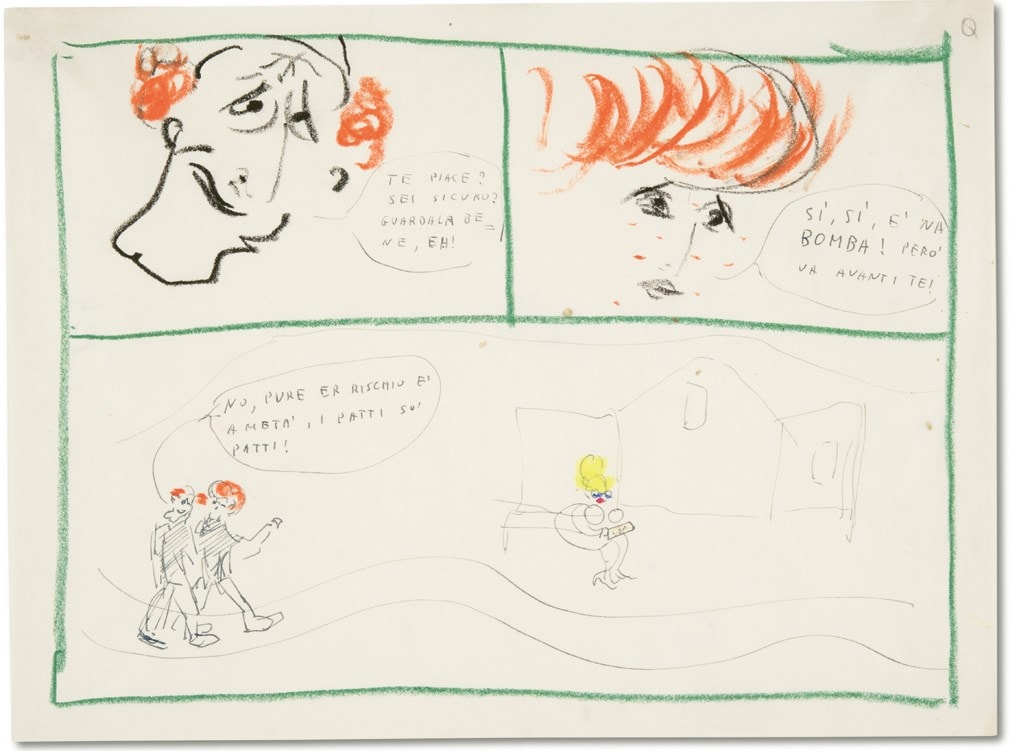

It’s hard to recall the exact moment (I first discovered his work), but it would be around the time I started (my) Masters at Central St Martins. Louise Wilson had made reading and film lists that we received prior to starting on the course which I’m fairly sure included Pasolini. His name had been on the periphery of my consciousness for a while, and my younger brother Ryan had spoken highly of him, especially in relation to Salò. I looked him up prior to seeing any of the films and watched a short interview with him that was published by the Criterion Channel. It was really this that captivated me and made me want to see his work. He speaks of the people he loves the most as “very plain, simple people”, non-intellectuals that “always have a certain grace”. He makes the distinction that unlike the petite bourgeoisie, they are not “corrupted by culture”. This really resonated with me, because when I talk about my work with a stranger, my preference is always this type of person. Whilst it’s clearly not his greatest work, The Canterbury Tales stands out – which at face value is possibly the most uninteresting and obvious choice visually, for me. However, it’s not the visual aspect alone that I find captivating about this film, it’s more the way it’s made, which lots of film buffs criticise but in contrast I find particularly enchanting. It has a chaos to it, a slapdash energy and playfulness that I find very appealing. The way in which Pasolini shows his disdain for societal hierarchy in the film is comedic, yet very effective in demonstrating the ludicrous nature of each narrative. His political commentary feels more relevant than ever, in the current climate.

Bruce LaBruce, photographer and filmmaker

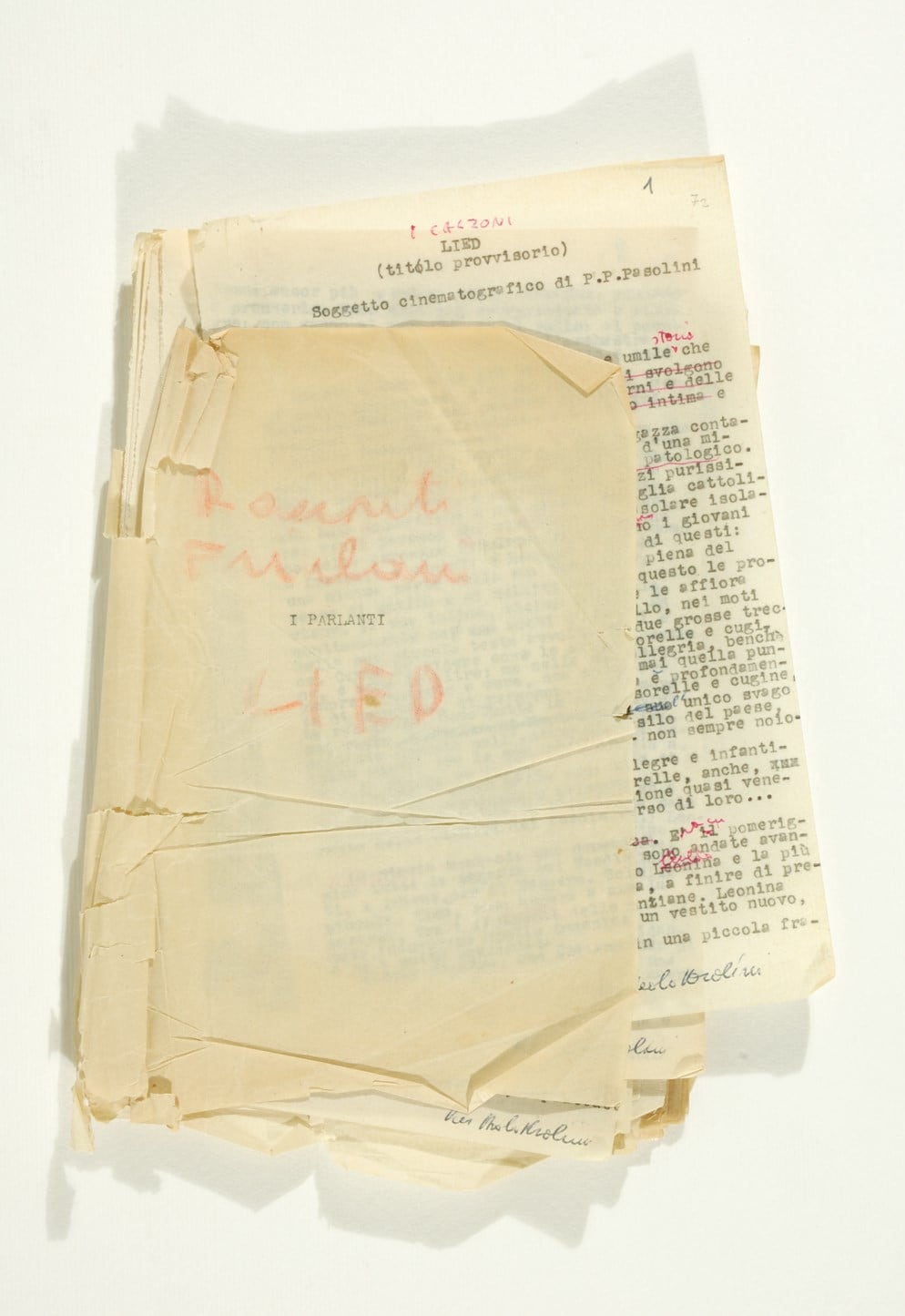

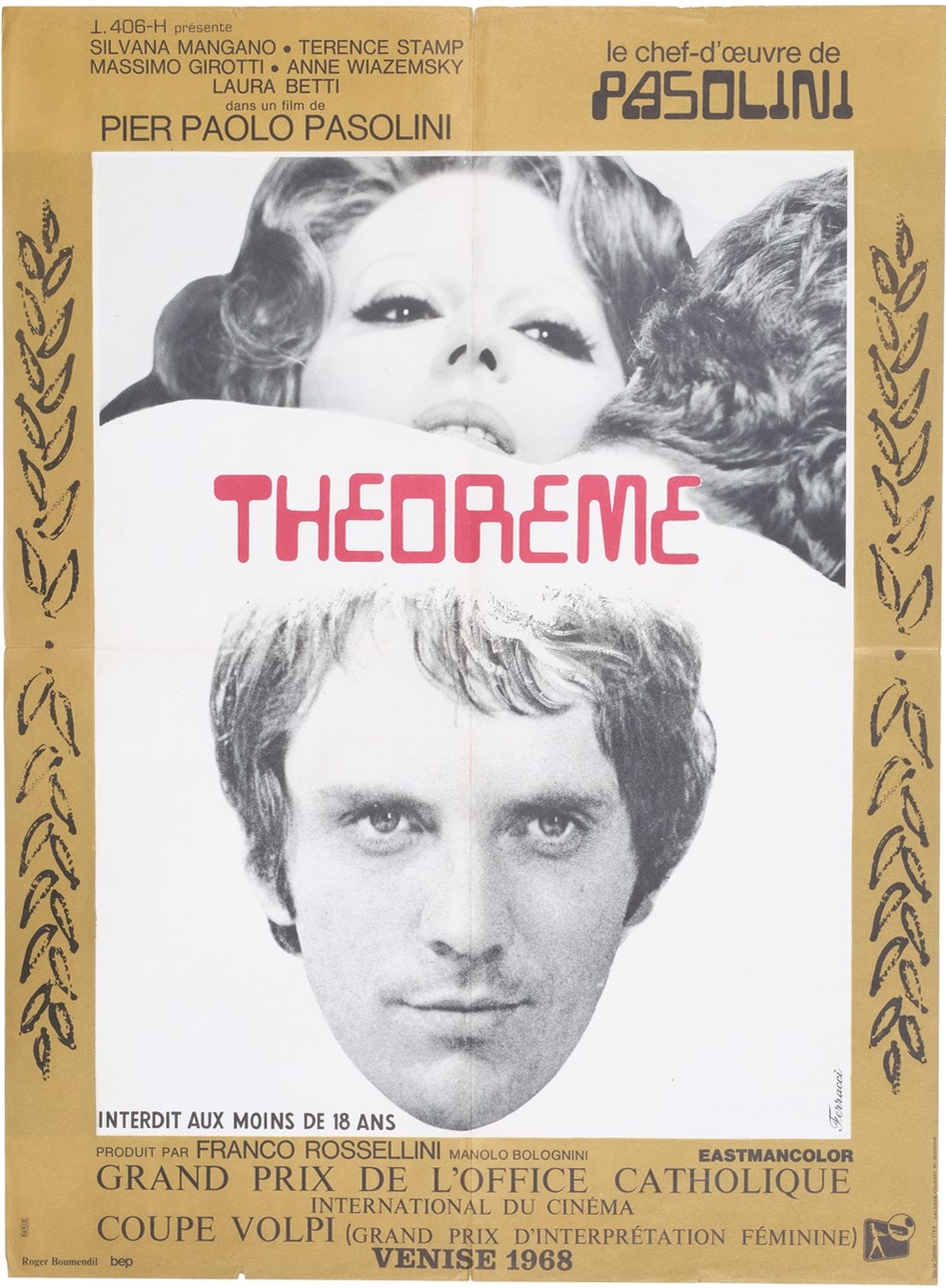

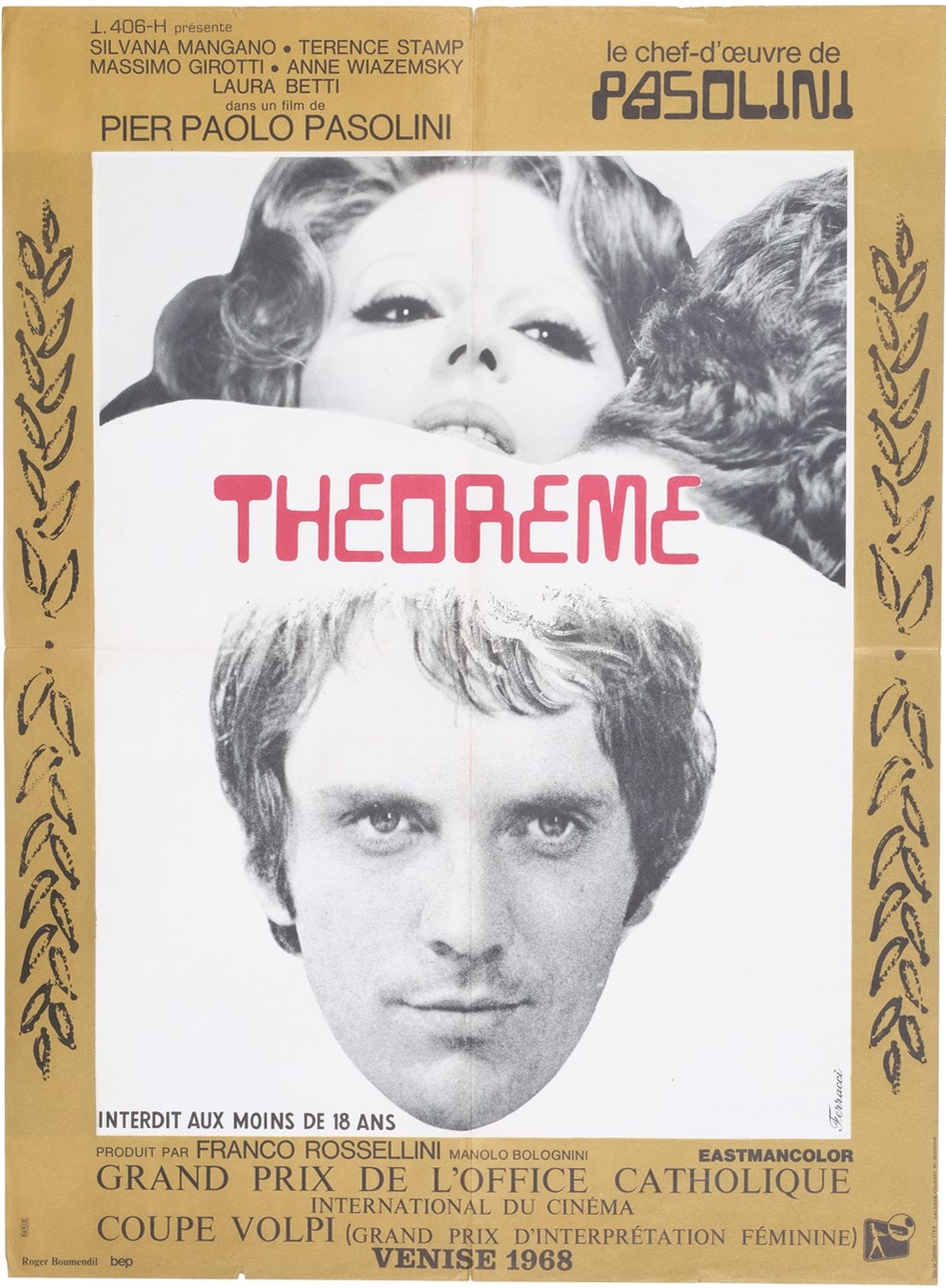

I’m a huge Pasolini aficionado, someone who still agonizes over the time-worn riddle of his death: was he randomly murdered by hustlers, or were they paid in a conspiracy to assassinate him just before his magnum opus and most controversial film, Salò, was to be released. (It’s the sign of a great filmmaker that so many people wanted him dead!) I’ve loved his movies since I was a film student in Toronto in the eighties, when I watched badly dubbed, scratchy prints of his Life trilogy. At the time I thought it was softcore pornography, which in a way, for me anyway, it was. When I saw Teorema at a rep cinema shortly after, it had a profound effect on me, so much so that I had wanted to remake it for many years, which I finally accomplished with my latest movie The Visitor.

The narrative of Teorema has an interloper infiltrate a bourgeois Milanese family which he disrupts by having sex with them all, including the maid, leading each to a transformation or liberation. It’s also a movie about psychosexual relationships, including Freud’s concept of Family Romance, the sexual attraction between members of the nuclear family unit, and the strict taboo against it, which results in repression and shame. Teorema comments on the modern alienation of industrialized society. My reimagining of it reflects a more contemporary political landscape, recasting the interloper as an immigrant; a black refugee. My movie also reimagines the original using contemporary queer aesthetics and cultural politics to tell the story, including the casting of a trans masculine actor as the daughter. I also reference Salò and Pasolini’s great film Porcile in my movie, the two films, along with Teorema, that completed his final trilogy of the psychopathology of the bourgeoisie. Finally, my film is a “pornification” of Pasolini, a direction which I believe he may have himself pursued had he lived longer. It was the master’s balance of dialectical impulses–as a Catholic, a Marxist, an atheist, and a homosexual – that elevated his work to the pantheon of great artists.

These New Puritans (Jack Barnett), musician

I entered Pasolini’s world through Medea and worked my way back to reality via his earlier films. The electricity of Maria Callas’ gaze was enough to transfix me. Once I reached reality, what struck me was how he treated the lowest like saints, a shanty town hovel like a cathedral. What could be seen by another eye as a grotesque face is treated like an icon. That tension between violence and poetry, between mythology and reality, is one that’s always resonated with me. In the words of Captain Beefheart, “tonight there be ice cream, ice cream for crow.”

Eileen Myles, writer and poet

A biography of Pasolini came to me in the 1990s probably through one of my publishers, when I was going through a breakup with a filmmaker. I wanted to be a filmmaker (myself), so I took Pasolini as my model because he was a poet and a lover (and an anthologizer) of dialects – which is a great way to think of films. I was staying in my sorrow in a friend’s house in the country and got DVDs of each Pasolini film. I was transformed not (only) into a filmmaker but a better writer, I think. His essay The Long Take, about editing and mortality, is one of the best things I’ve ever read. He was a genius among many things, an artist who managed – until he didn’t – to break all rules as to what a person could be, or say, or do publicly. They didn’t stop him in his death, (they only) canonized him. I still think of myself as a filmmaker dreaming of being a writer, thanks to him.

Colleen Kelsey, film journalist

In college, I spent a lot of time in the far back corner of the library – in what was called the media room – watching movies marked “special material,” i.e., films too important to loan out. Though I was an early convert to Buñuel’s icy satire and Fassbinder’s operatic cruelty, Pasolini was intimidating. With his reputation, I was unsure what I would find. Soon, I would realize that the sensibility I anticipated – a violent synthesis of ecstasy and degradation – was what I responded to in his films. A decade later, I saw Medea (1969) on 35mm in downtown Manhattan, less than a hundred blocks from where my affinity for Pasolini began. That it was Maria Callas’ only film role was something I found romantic, filmed after Aristotle Onassis left her for Jackie O., and with one of her closest confidants. (It’s been said that Pasolini told Callas she was the only woman he’d ever loved…aside from his mother.) Lurid with sun-scorched landscapes, Piero Tosi’s wildly intricate costumes, and music chosen in collaboration with the Italian writer Elsa Morante, Medea articulates Pasolini’s mythic interpretation of the dispossessed. Callas’ performance is an explosion, lending the film’s destructive beauty true volatility. I find Pasolini’s genius in his commitment to confrontation. An ancient text, made novel. Deviance, made essential.

Durga Chew-Bose, writer and filmmaker

“On this blurry shot, ‘Ciao, Pier Paolo Pasolini.’” The year is 1967 and the voice of Agnès Varda bids a gentle adieu to the Italian director, following a quick, three minute exchange set against New York City’s 42nd street. The whir of passersby, the saturated grit of 16mm, and the streaks of red and yellow neon – all of it – find harmony with Pasolini’s words, his musings about his obscure relationship to religion, his painterly approach to the frame, and cinema’s hold on reality vs. fiction. It’s a brief encounter, uncoerced and profuse. It’s Pasolini in a bottle. It’s Pasolini sings the blues. It’s Pasolini exactly as we’ve come to know him – even out of focus… forever persuasive, poetic.

Willem Dafoe, actor

My interest in Pier Paolo Pasolini started some maybe 40 years ago when Mark Rappaport, a New York independent filmmaker, started speaking to me about participating in some abstract film about him (the film never happened). In that period, I watched Salò and Teorema. Then when Martin Scorsese cast me in The Last Temptation of Christ, he told me to watch The Gospel According to Matthew to give me an idea of the essential (I guess) Neo-Realist tradition he wanted to approach for the shoot. When I started living in Italy around 2005, and my Roman wife gave me a crash course in Italian cinema, I saw pretty much everything he shot or wrote. Then, in preparation for Pasolini by Abel Ferrara, I started reading not only biographical material and his poetry, but watching interviews, shorts and his documentary Comizi d’Amore. Above all, I was impressed by his Corsair Writings on the “anthropological revolution” in Italy. As if he were a seer, many ideas he posited were incredibly prescient. I mention all these different aspects of his work because I cannot separate them from his films – and his films are as varied as his ever-challenging intellectual inquiry. Some I like a great deal, some are clunky – but I always forgive imperfection, because he was such a free thinking and inspiring artist. To partially put his cinema into context, I always think about the fact that he shot the scruffy Salò at the same time Bertolucci was shooting the lush 1900 only kilometers away near Parma in the spring of 1975. There’s even a documentary about a soccer match that these very different crews played against each other, Centoventi contro Novecento. His vision was singular and unique, and it stays with me.

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale now. Order here.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImagePier Paolo Pasolini, Autoritratto col fiore in bocca (Self-portrait with a flower in her mouth), oil on hardboard, 1947Florence Pasolini archive material courtesy of Archivio Contemporaneo Vieusseux and Graziella Chiarcossi

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale now. Order here.

Olivia Laing, author

Pier Paolo Pasolini: prophet. He saw what was coming, and Salò, that apocalyptic masterpiece, was his final warning. Almost his last recorded sentence, a few hours before his brutal murder, was “we are all in danger”, siamo tutti in pericolo. Wasn’t he right about that? He warned that capitalism was the new fascism, he dared to say that fireflies were worth more than the industrialisation that was poisoning the Italy he loved. He was a knot of complexities that do not resolve into easy slogans. He inhabited a night-world and left behind him a trail of irreconcilable visions, unlike anything else in cinema. When I wrote The Silver Book (which comes out on November 6 via Penguin), I wanted him to be a mystery even to his closest friends: driven, enigmatic, unknowable, gentle, always working, always alone. I read somewhere that nobody cared about his murder, but the record shows the opposite. The whole vast space of Campo de’ Fiori was packed for his funeral. The street boys he championed, fucked, befriended, placed at the centre of the story: they all came out for him and when the coffin was carried through the crowd, they raised their fists in valediction.

John Alexander Skelton, fashion designer

It’s hard to recall the exact moment (I first discovered his work), but it would be around the time I started (my) Masters at Central St Martins. Louise Wilson had made reading and film lists that we received prior to starting on the course which I’m fairly sure included Pasolini. His name had been on the periphery of my consciousness for a while, and my younger brother Ryan had spoken highly of him, especially in relation to Salò. I looked him up prior to seeing any of the films and watched a short interview with him that was published by the Criterion Channel. It was really this that captivated me and made me want to see his work. He speaks of the people he loves the most as “very plain, simple people”, non-intellectuals that “always have a certain grace”. He makes the distinction that unlike the petite bourgeoisie, they are not “corrupted by culture”. This really resonated with me, because when I talk about my work with a stranger, my preference is always this type of person. Whilst it’s clearly not his greatest work, The Canterbury Tales stands out – which at face value is possibly the most uninteresting and obvious choice visually, for me. However, it’s not the visual aspect alone that I find captivating about this film, it’s more the way it’s made, which lots of film buffs criticise but in contrast I find particularly enchanting. It has a chaos to it, a slapdash energy and playfulness that I find very appealing. The way in which Pasolini shows his disdain for societal hierarchy in the film is comedic, yet very effective in demonstrating the ludicrous nature of each narrative. His political commentary feels more relevant than ever, in the current climate.

Bruce LaBruce, photographer and filmmaker

I’m a huge Pasolini aficionado, someone who still agonizes over the time-worn riddle of his death: was he randomly murdered by hustlers, or were they paid in a conspiracy to assassinate him just before his magnum opus and most controversial film, Salò, was to be released. (It’s the sign of a great filmmaker that so many people wanted him dead!) I’ve loved his movies since I was a film student in Toronto in the eighties, when I watched badly dubbed, scratchy prints of his Life trilogy. At the time I thought it was softcore pornography, which in a way, for me anyway, it was. When I saw Teorema at a rep cinema shortly after, it had a profound effect on me, so much so that I had wanted to remake it for many years, which I finally accomplished with my latest movie The Visitor.

The narrative of Teorema has an interloper infiltrate a bourgeois Milanese family which he disrupts by having sex with them all, including the maid, leading each to a transformation or liberation. It’s also a movie about psychosexual relationships, including Freud’s concept of Family Romance, the sexual attraction between members of the nuclear family unit, and the strict taboo against it, which results in repression and shame. Teorema comments on the modern alienation of industrialized society. My reimagining of it reflects a more contemporary political landscape, recasting the interloper as an immigrant; a black refugee. My movie also reimagines the original using contemporary queer aesthetics and cultural politics to tell the story, including the casting of a trans masculine actor as the daughter. I also reference Salò and Pasolini’s great film Porcile in my movie, the two films, along with Teorema, that completed his final trilogy of the psychopathology of the bourgeoisie. Finally, my film is a “pornification” of Pasolini, a direction which I believe he may have himself pursued had he lived longer. It was the master’s balance of dialectical impulses–as a Catholic, a Marxist, an atheist, and a homosexual – that elevated his work to the pantheon of great artists.

These New Puritans (Jack Barnett), musician

I entered Pasolini’s world through Medea and worked my way back to reality via his earlier films. The electricity of Maria Callas’ gaze was enough to transfix me. Once I reached reality, what struck me was how he treated the lowest like saints, a shanty town hovel like a cathedral. What could be seen by another eye as a grotesque face is treated like an icon. That tension between violence and poetry, between mythology and reality, is one that’s always resonated with me. In the words of Captain Beefheart, “tonight there be ice cream, ice cream for crow.”

Eileen Myles, writer and poet

A biography of Pasolini came to me in the 1990s probably through one of my publishers, when I was going through a breakup with a filmmaker. I wanted to be a filmmaker (myself), so I took Pasolini as my model because he was a poet and a lover (and an anthologizer) of dialects – which is a great way to think of films. I was staying in my sorrow in a friend’s house in the country and got DVDs of each Pasolini film. I was transformed not (only) into a filmmaker but a better writer, I think. His essay The Long Take, about editing and mortality, is one of the best things I’ve ever read. He was a genius among many things, an artist who managed – until he didn’t – to break all rules as to what a person could be, or say, or do publicly. They didn’t stop him in his death, (they only) canonized him. I still think of myself as a filmmaker dreaming of being a writer, thanks to him.

Colleen Kelsey, film journalist

In college, I spent a lot of time in the far back corner of the library – in what was called the media room – watching movies marked “special material,” i.e., films too important to loan out. Though I was an early convert to Buñuel’s icy satire and Fassbinder’s operatic cruelty, Pasolini was intimidating. With his reputation, I was unsure what I would find. Soon, I would realize that the sensibility I anticipated – a violent synthesis of ecstasy and degradation – was what I responded to in his films. A decade later, I saw Medea (1969) on 35mm in downtown Manhattan, less than a hundred blocks from where my affinity for Pasolini began. That it was Maria Callas’ only film role was something I found romantic, filmed after Aristotle Onassis left her for Jackie O., and with one of her closest confidants. (It’s been said that Pasolini told Callas she was the only woman he’d ever loved…aside from his mother.) Lurid with sun-scorched landscapes, Piero Tosi’s wildly intricate costumes, and music chosen in collaboration with the Italian writer Elsa Morante, Medea articulates Pasolini’s mythic interpretation of the dispossessed. Callas’ performance is an explosion, lending the film’s destructive beauty true volatility. I find Pasolini’s genius in his commitment to confrontation. An ancient text, made novel. Deviance, made essential.

Durga Chew-Bose, writer and filmmaker

“On this blurry shot, ‘Ciao, Pier Paolo Pasolini.’” The year is 1967 and the voice of Agnès Varda bids a gentle adieu to the Italian director, following a quick, three minute exchange set against New York City’s 42nd street. The whir of passersby, the saturated grit of 16mm, and the streaks of red and yellow neon – all of it – find harmony with Pasolini’s words, his musings about his obscure relationship to religion, his painterly approach to the frame, and cinema’s hold on reality vs. fiction. It’s a brief encounter, uncoerced and profuse. It’s Pasolini in a bottle. It’s Pasolini sings the blues. It’s Pasolini exactly as we’ve come to know him – even out of focus… forever persuasive, poetic.

Willem Dafoe, actor

My interest in Pier Paolo Pasolini started some maybe 40 years ago when Mark Rappaport, a New York independent filmmaker, started speaking to me about participating in some abstract film about him (the film never happened). In that period, I watched Salò and Teorema. Then when Martin Scorsese cast me in The Last Temptation of Christ, he told me to watch The Gospel According to Matthew to give me an idea of the essential (I guess) Neo-Realist tradition he wanted to approach for the shoot. When I started living in Italy around 2005, and my Roman wife gave me a crash course in Italian cinema, I saw pretty much everything he shot or wrote. Then, in preparation for Pasolini by Abel Ferrara, I started reading not only biographical material and his poetry, but watching interviews, shorts and his documentary Comizi d’Amore. Above all, I was impressed by his Corsair Writings on the “anthropological revolution” in Italy. As if he were a seer, many ideas he posited were incredibly prescient. I mention all these different aspects of his work because I cannot separate them from his films – and his films are as varied as his ever-challenging intellectual inquiry. Some I like a great deal, some are clunky – but I always forgive imperfection, because he was such a free thinking and inspiring artist. To partially put his cinema into context, I always think about the fact that he shot the scruffy Salò at the same time Bertolucci was shooting the lush 1900 only kilometers away near Parma in the spring of 1975. There’s even a documentary about a soccer match that these very different crews played against each other, Centoventi contro Novecento. His vision was singular and unique, and it stays with me.

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale now. Order here.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.