Rewrite

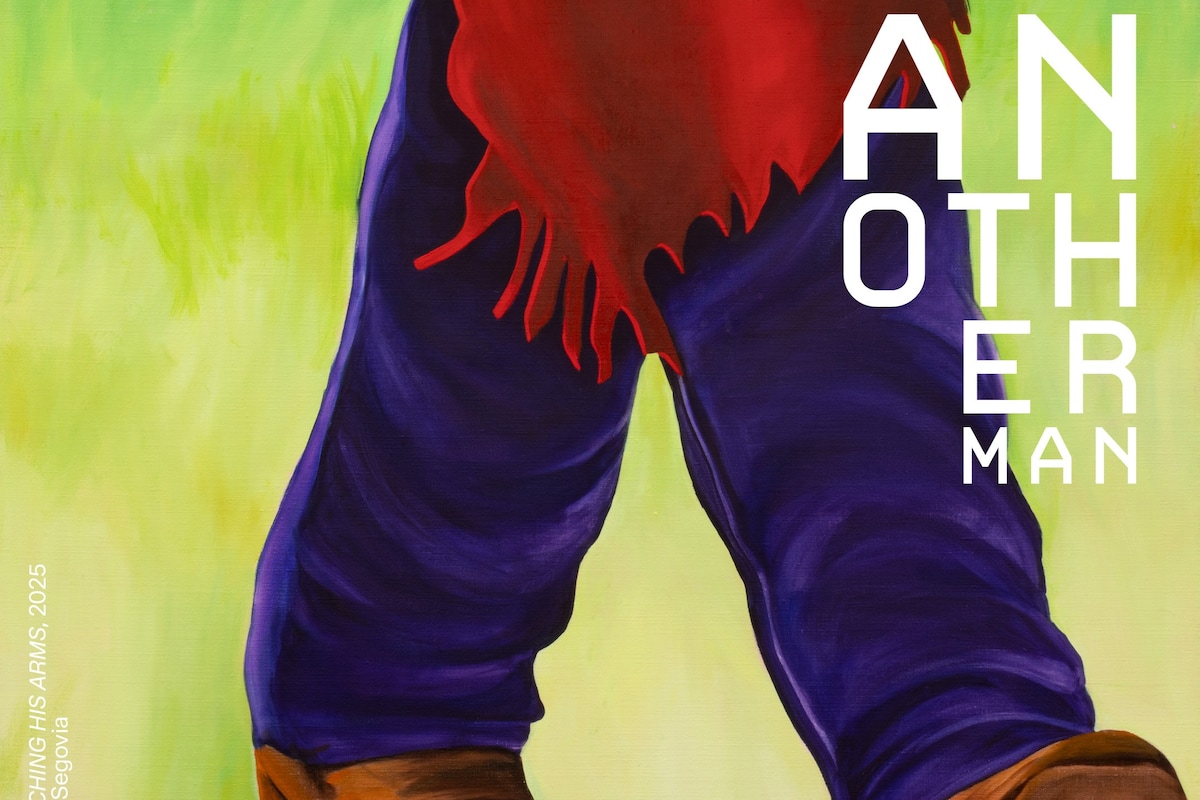

Lead ImageRamón Stretching his Arms, 2025Artwork by Ana Segovia. Courtesy of the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from October 30. Pre-order here.

I was kind of stuck, wondering what’s next, and thinking about the next thing as a departure. I was like, “Have I outgrown the cowboy?” And while I was waiting for the stretchers to come, I decided to just paint what I knew. So I went back to the cowboy, almost like an instinct, only this time something different happened. The subject matter stayed the same – it’s still about the cowboy’s type of masculinity, but the color palette completely exploded in a different way. I’m calling it the Ramón series.

My previous work was exploring the sarcastic, sardonic sense of humor to disarm that masculinity. Here, I think it was a little bit more earnest about the eros around the figure, and I think it had everything to do with the color palette, this cadmium red that gives this sort of erotic tension, and signals to this draggy sort of culture, where the chaps become go-go boots.

There is this sensuousness that I’ve always shied away from for fear of romanticizing masculinity, rather than poking fun at it. So I was excited all over again, because I realized it’s not even about a repetitive subject matter. It’s about the approach to that that shifts and becomes exciting for me to try to figure out.

I really wanted to insist on the fantastical, like this could be anywhere, but it’s probably nowhere. I wanted to be deliberate about making a body of work that felt like it was occurring at the same time of day, creating an ambiance and insisting on the cadmium red and blue jeans and these moments of color that ignite. I was trying to figure out how color relations could signify, conceptually, eros. So everything is in service of that cadmium red. Red is what’s framing the crotch and the ass.

I’m always thinking about three things in art that are important to my process: humor, eros, and aggression. In my previous work, humor was a much larger component, and in the Ramón series, the sense of humor comes from the titles, and from the framing of the body: it’s all crotches and asses. But the titles signal to Ramón doing an activity outside the frame. So the titles are like, “Ramón Eating an Apple,” but really you’re just looking at his ass.

When that occurs offscreen in film, it’s mostly sound. We hear something that we can’t see and it signals towards an activity or an action or an anticipation. There’s a tension between wanting to see something that you can’t, but then you’re forced to see that one part of the body. Any kind of visual art that contains and frames something visible is always a statement about everything that isn’t there. This is a direct sort of way of trying to comment on that, and why it becomes so important that we’re looking at this guy’s crotch.

The B-Western movies were sort of pulpy, bad movies, but they were the most important genre in Mexico. And then that went out of style, but the movies never did. They weren’t in the mainstream, but they were still being consumed, even in literature and painting. And it’s just like: why are we so attracted to that myth? The cinematic cowboy is completely mythical. We don’t get bored. Why? I think that’s an exciting question.

The hyper-sexualised male is always a cowboy, or a calendar of like, super-hot firemen. And who is this content for? Women and gay men. I’ve been thinking about the history of the hypersexual male body and the difference between the agency that the male body has, versus the female body. There’s a question here about how, when you sexualize masculinity in that way, the power doesn’t shift from the male body; it’s empowered. When you eroticize the female body it really is objectifying, it really does take away a lot of power and agency.

Tom of Finland is my favorite artist, because he had those things that I care about deeply: aggression, eros, and humor. I find that combination intoxicatingly powerful, and it really elevates the experience of looking at a work of art from, say, the pornographic or illustrative, to an interaction that creates this triangle of sensations that can’t be pinned down. It stays with you in a way that’s different from looking at a picture of the Marlboro man.

Ramón is my fantasy of who I want to be, or think I am the weird thing that happens where I picture myself as this big, strong, macho guy and then I see myself in the mirror and I’m shocked to realize that I’m not Ramón physically. But I think that Ramón has always been there. He’s a part of me, even right now.

It goes back to desire. Anne Carson is the most important translator of Sappho, and in Eros the Bittersweet, through a Sappho fragment, she talks about “desire” as a verb not just desiring a tangible thing, but desire more broadly. When I think about the trans experience, desire is such an important part of (it), because it’s not just this erotic desire towards a third person – it’s an erotic desire to oneself. Anne Carson understands that Sappho understands that the heart of desire is composed of the unattainable. And once it’s attained, desire shifts.

My relationship to Ramón is this unattainable man, an eros that’s reflected back to myself through an image that I find impossible to actually embody. And that I shouldn’t even, right? Because it’s the most toxic form of masculinity. So I shouldn’t strive for that, but it burns inside this ardent desire to see myself as Ramón.

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from October 30. Pre-order here.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageRamón Stretching his Arms, 2025Artwork by Ana Segovia. Courtesy of the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from October 30. Pre-order here.

I was kind of stuck, wondering what’s next, and thinking about the next thing as a departure. I was like, “Have I outgrown the cowboy?” And while I was waiting for the stretchers to come, I decided to just paint what I knew. So I went back to the cowboy, almost like an instinct, only this time something different happened. The subject matter stayed the same – it’s still about the cowboy’s type of masculinity, but the color palette completely exploded in a different way. I’m calling it the Ramón series.

My previous work was exploring the sarcastic, sardonic sense of humor to disarm that masculinity. Here, I think it was a little bit more earnest about the eros around the figure, and I think it had everything to do with the color palette, this cadmium red that gives this sort of erotic tension, and signals to this draggy sort of culture, where the chaps become go-go boots.

There is this sensuousness that I’ve always shied away from for fear of romanticizing masculinity, rather than poking fun at it. So I was excited all over again, because I realized it’s not even about a repetitive subject matter. It’s about the approach to that that shifts and becomes exciting for me to try to figure out.

I really wanted to insist on the fantastical, like this could be anywhere, but it’s probably nowhere. I wanted to be deliberate about making a body of work that felt like it was occurring at the same time of day, creating an ambiance and insisting on the cadmium red and blue jeans and these moments of color that ignite. I was trying to figure out how color relations could signify, conceptually, eros. So everything is in service of that cadmium red. Red is what’s framing the crotch and the ass.

I’m always thinking about three things in art that are important to my process: humor, eros, and aggression. In my previous work, humor was a much larger component, and in the Ramón series, the sense of humor comes from the titles, and from the framing of the body: it’s all crotches and asses. But the titles signal to Ramón doing an activity outside the frame. So the titles are like, “Ramón Eating an Apple,” but really you’re just looking at his ass.

When that occurs offscreen in film, it’s mostly sound. We hear something that we can’t see and it signals towards an activity or an action or an anticipation. There’s a tension between wanting to see something that you can’t, but then you’re forced to see that one part of the body. Any kind of visual art that contains and frames something visible is always a statement about everything that isn’t there. This is a direct sort of way of trying to comment on that, and why it becomes so important that we’re looking at this guy’s crotch.

The B-Western movies were sort of pulpy, bad movies, but they were the most important genre in Mexico. And then that went out of style, but the movies never did. They weren’t in the mainstream, but they were still being consumed, even in literature and painting. And it’s just like: why are we so attracted to that myth? The cinematic cowboy is completely mythical. We don’t get bored. Why? I think that’s an exciting question.

The hyper-sexualised male is always a cowboy, or a calendar of like, super-hot firemen. And who is this content for? Women and gay men. I’ve been thinking about the history of the hypersexual male body and the difference between the agency that the male body has, versus the female body. There’s a question here about how, when you sexualize masculinity in that way, the power doesn’t shift from the male body; it’s empowered. When you eroticize the female body it really is objectifying, it really does take away a lot of power and agency.

Tom of Finland is my favorite artist, because he had those things that I care about deeply: aggression, eros, and humor. I find that combination intoxicatingly powerful, and it really elevates the experience of looking at a work of art from, say, the pornographic or illustrative, to an interaction that creates this triangle of sensations that can’t be pinned down. It stays with you in a way that’s different from looking at a picture of the Marlboro man.

Ramón is my fantasy of who I want to be, or think I am the weird thing that happens where I picture myself as this big, strong, macho guy and then I see myself in the mirror and I’m shocked to realize that I’m not Ramón physically. But I think that Ramón has always been there. He’s a part of me, even right now.

It goes back to desire. Anne Carson is the most important translator of Sappho, and in Eros the Bittersweet, through a Sappho fragment, she talks about “desire” as a verb not just desiring a tangible thing, but desire more broadly. When I think about the trans experience, desire is such an important part of (it), because it’s not just this erotic desire towards a third person – it’s an erotic desire to oneself. Anne Carson understands that Sappho understands that the heart of desire is composed of the unattainable. And once it’s attained, desire shifts.

My relationship to Ramón is this unattainable man, an eros that’s reflected back to myself through an image that I find impossible to actually embody. And that I shouldn’t even, right? Because it’s the most toxic form of masculinity. So I shouldn’t strive for that, but it burns inside this ardent desire to see myself as Ramón.

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from October 30. Pre-order here.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.