Rewrite

目次

- 1 Ahead of the release of a new documentary about the late singer and actress, we return to the pages of the Spring/Summer 2015 issue, where the inimitable artist shared her most treasured texts

- 2 Late Victorian Holocaust by Nick Cave

- 3 Bomb by Gregory Corso

- 4 The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

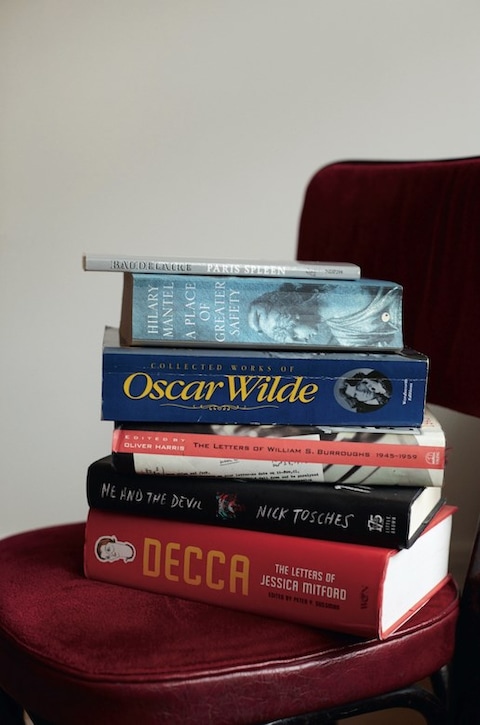

- 5 Paris Spleen by Charles Baudelaire

- 6 The Last Days of Mankind by Frank McGuinness

- 7 A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel

- 8 Manifesto: Woman and Painting by Marlene Dumas

- 9 In the Hand of Dante by Nick Tosches

- 10 Silent Highway by Anthony Howell

- 11 Further Reading

- 12 Ahead of the release of a new documentary about the late singer and actress, we return to the pages of the Spring/Summer 2015 issue, where the inimitable artist shared her most treasured texts

- 13 Late Victorian Holocaust by Nick Cave

- 14 Bomb by Gregory Corso

- 15 The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

- 16 Paris Spleen by Charles Baudelaire

- 17 The Last Days of Mankind by Frank McGuinness

- 18 A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel

- 19 Manifesto: Woman and Painting by Marlene Dumas

- 20 In the Hand of Dante by Nick Tosches

- 21 Silent Highway by Anthony Howell

- 22 Further Reading

Ahead of the release of a new documentary about the late singer and actress, we return to the pages of the Spring/Summer 2015 issue, where the inimitable artist shared her most treasured texts

This story is taken from the Spring/Summer 2015 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Imagine the following a salon of sorts, with Marianne Faithfull in the chair. You have to keep up, with Marianne. She’s fiercely well-read, steeped in and fuelled by an exuberant, riotous love of literature. Discussing those decadent writer heroes of hers – Oscar Wilde, Baudelaire – she has a lovely knack of making you feel as if they’re old friends who might drop by at any moment, rather than brittle names chiselled into stone in Père Lachaise or Montparnasse cemeteries. Her conversation skips across time and geography, from Weimar Berlin to Shelley to The Jungle Book to Mick Jagger’s old love letters.

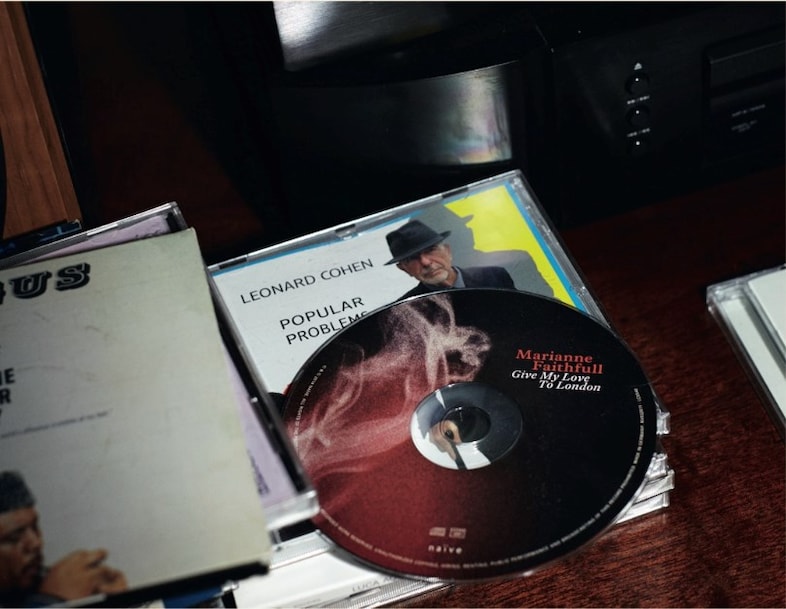

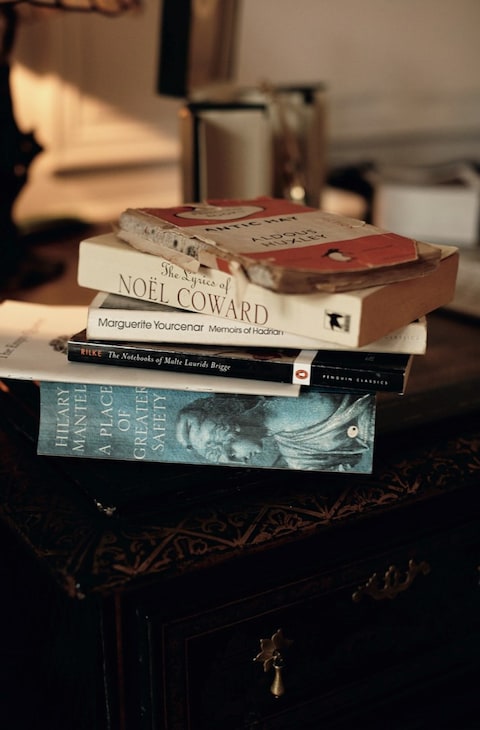

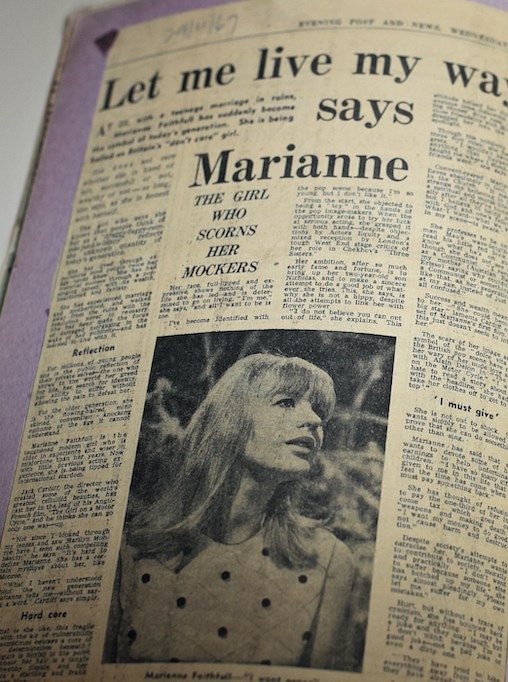

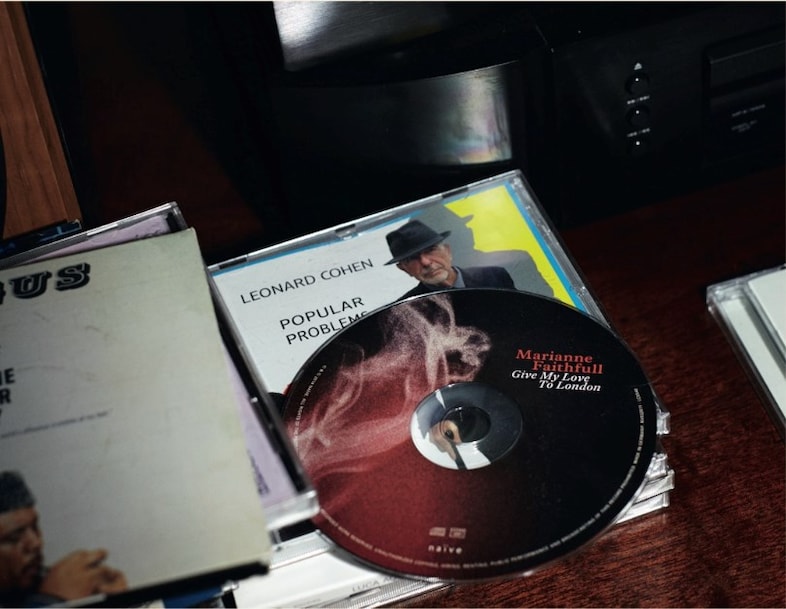

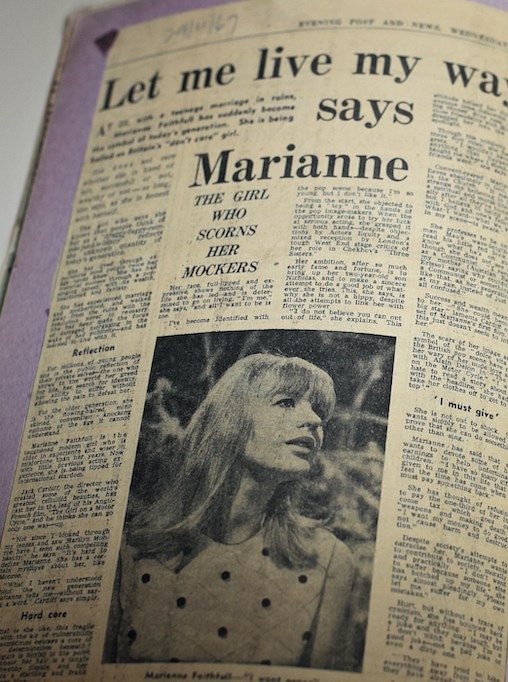

We met Marianne in a London hotel room when she was mid-way through her 50th anniversary tour. Over the evening – alternating between sipping tea and an e-cigarette – she conjured enough ideas to fill the Document twice over. Which is not to say she hasn’t got definite tastes; some authors were dismissed as “total shit”, at the mention of others she looked like she’d swallowed a light bulb and reeled off verses in a reverie. A few weeks later we visited her Paris apartment to shoot the photographs featured here. Her rooms are an Aladdin’s cave of mementos and talismans from a life worthy of fiction, a life Wilde or Rimbaud would have approved of. On the walls were newspaper clippings from the infamous Redlands bust (“girl in a fur-skin rug”), photographs of William Burroughs, sketches by her rock ‘n’ roll partner in crime, Anita Pallenberg, and books, hundreds of well-thumbed books jostling for space on her shelves.

Marianne’s original plan for this Document was to focus on English literature, in a vain attempt to narrow down her sweeping, kaleidoscopic knowledge into these 32 pages. But soon she was discussing her friends – Nick Cave, Gregory Corso – and the selection inevitably widened into this snapshot – by no means definitive – of writers whose words she holds close to her heart. Those that made it in: Charles Baudelaire, Nick Cave, Gregory Corso, Anthony Howell, Hilary Mantel, Frank McGuinness, Nick Tosches and Oscar Wilde. There were so many more we didn’t have room for; some are listed as Further Reading, which includes many authors Marianne first discovered as a teenage convent girl. When the nuns gave her the Index, the Catholic Church’s list of forbidden books, it changed her life in a way they certainly didn’t intend. She decided to read every single one of those “heretical” texts, an appropriate training in decadence for her life to come. “It was a good place to start …” she says.

Late Victorian Holocaust by Nick Cave

“Nick wrote this song for me. He said Late Victorian Holocaust was about a girl getting up to mischief in London. I think that sums it up! Being very young, very silly, very naughty and very sad. It’s wonderful. I don’t think of lyrics as poetry. To me lyrics are lyrics and poetry is poetry, they’re quite separate. The only person who’s close is Nick Cave.”

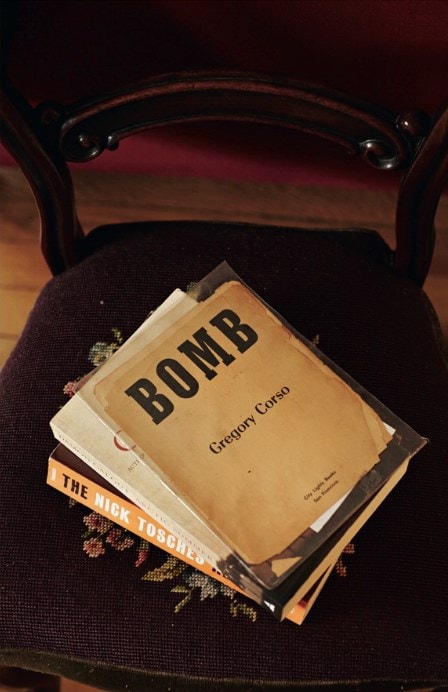

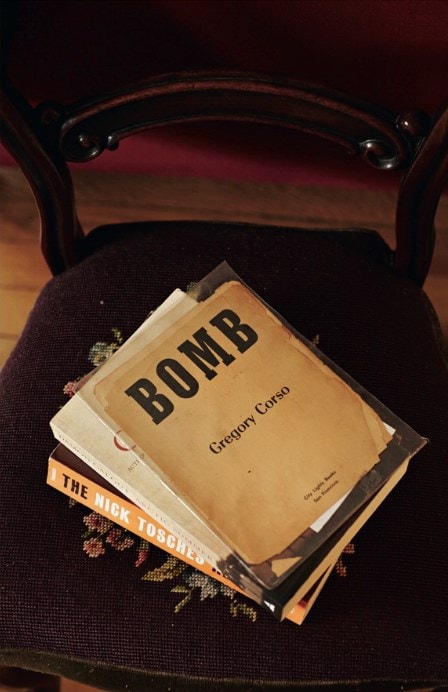

Bomb by Gregory Corso

“Gregory was my favourite. He was the naughtiest. He was impossible, but so sweet and very good-looking. He really is the greatest poet I think, even though Allen is wonderful of course, and Burroughs. I met Gregory at the Beat Hotel, at 9 rue Git-le-Coeur in Paris, where he wrote Bomb. He was on Brompton mixture at the time, which is half heroin, half cocaine, a liquid they give to cancer patients. So I didn’t really ‘meet’ Gregory then exactly, he was comatose. Occasionally he would wake up, take some more Brompton mixture and go out again.

“As a young man Gregory spent a lot of time in jail, he was a hellraiser. When he got out of jail and met Allen Ginsberg, he showed Al what he’d written, and Al said, “You’re a poet. That’s it, you’re the next Shelley.” And he was. What Allen and I knew was that as long as Gregory had a little room, rather like a cell, with just a typewriter, a bit of food, no alcohol, and no company, he would work, he would write beautiful, beautiful things. So strange how awful things can help you – he was quite happy in a small space with books and a typewriter and an idea. He didn’t even need a view. That was how he wrote. But when he went out socialising, he would get drunk. And then he was impossible. But what could you do?

“You couldn’t stop Gregory. Allen tried. He was a bit in love with Gregory. Everyone was a bit in love with Gregory. And Gregory was a bit in love with me, too.”

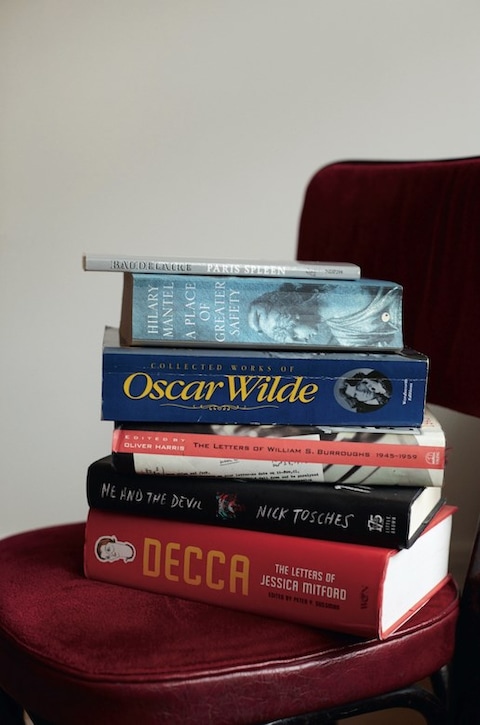

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

“From the corner of the divan of Persian saddle-bags on which he was lying, smoking, as was his custom, innumerable opium-tainted cigarettes …” The Picture Of Dorian Gray was the first really decadent book I read; I read it very young and it changed my life. It was all uphill after that. What I know, and what I hope you know too, is that to be decadent is not to mean that you need to smoke opium-tainted cigarettes; it’s a state of mind, and Oscar had it. My favourite story about Oscar: When he was in Paris he met Paul Claudel, a great and very well-known dramatist and poet – everyone worshipped him at the time. He was devoutly Catholic and of course believed in God, and not Oscar. They would meet at parties, and disagree. When Oscar died, Claudel received a telegram the next day which read: “God does not exist. Oscar.” Even dying, Oscar had worked out how to deal with Paul Claudel! Naughty Oscar. He had to have the last word. Poor Claudel must have been hopping.“

Paris Spleen by Charles Baudelaire

“I first read Baudelaire when I was about 14 or 15: just perfect for corruption. At the convent we were given a list called the Index, all the forbidden books of literature, banned by the Catholic Church. On the Index is all the great literature of the world, going right back to Petronius, Le Rouge et le Noir, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Oscar Wilde … everything you could think of is on the Catholic Index. I remember we had a week’s retreat with a Jesuit priest and so my friend Sally Oldfield and I decided to put ourselves through a long, long training of reading everything on the list, and we nearly did. All the forbidden books of history. It was a good start …”

The Last Days of Mankind by Frank McGuinness

“I lived in Ireland for 15 years. In 1991, I played Pirate Jenny in The Threepenny Opera in Dublin, adapted from Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Will’s original by the playwright and poet Frank McGuinness. Frank’s from Buncrana in County Donegal. As he did the translation, he obviously had to approve of me playing Pirate Jenny, so he came up to Shell Cottage where I lived, and we had a wonderful time. We’ve worked a lot together over the years: he wrote, or helped me write, Sleep, The Wedding, After The Ceasefire, and The Old House on my record Horses and High Heels. When I can’t write and I get a block, I get hold of Frank. He does the job. I sit there reading the Daily Mirror with my feet up. I’ve got this theory that if you’re in the room, you help write the song. Not all musicians agree with me, but Frank does.

“The following piece came out of us wanting to do a song cycle together: I had been reading Karl Kraus – Kraus was a great writer. He had a really hip magazine in Vienna called Die Fackel, which translates as ‘The Torch’. He was Jewish, and he was appalled by the first world war. In 1919 he published a play, The Last Days Of Mankind, in a series of special Die Fackel issues. The play was three days long – not an easy production! It came from what he’d seen during the first world war and what he saw coming in the future, which made it very interesting for Frank and for me. Frank wrote the following translation of The Last Days Of Mankind, which was going to be a song, but we never managed to get it together. But I think it’s absolutely wonderful.”

A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel

“The first half of A Place of Greater Safety, about the French Revolution, is genius. The great characters in this book are Georges-Jacques Danton and Camille Desmoulins. “A la lanterne!” It was Camille who thought of that slogan. The French Revolution was a favourite subject of the Romantic poets and one of the things I love about living in Paris. I think you have to treat people differently here, because of the revolution. If you get into a taxi or go into a shop or do any kind of transaction in Paris, you have to say, “Bonjour Monsieur” or “Bonsoir Madame.” You can’t just do as they do in New York: “Take me to 42nd Street!” It doesn’t work. You have to treat people first as human beings and then as their job. This book was the first Hilary Mantel I read, and it turned me on to all her others.”

Manifesto: Woman and Painting by Marlene Dumas

“A few years ago, I curated an exhibition for the Tate Liverpool with John Dunbar, my first husband, who is a very good artist himself. It was fantastic fun. They gave me the whole of the Tate catalogue to play with, and I found a painting in the archives by Marlene Dumas of Ulrike Meinhof (co-founder of the Red Army Faction) lying dead on the prison floor in Stuttgart – a brilliant picture, which I put in the exhibition. That was the first I knew anything about Marlene at all. Two years later, I discovered that she had done a portrait of me. The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam explained they were doing a big Marlene retrospective and were showing my portrait. I went and met Marlene there, and I sang Broken English for her. This is her 1993 piece Woman and Painting, and the portrait, which hangs in my home.”

In the Hand of Dante by Nick Tosches

“My God, I’m a fan of Nick Tosches! I adore him. These extracts are from his novel In the Hand of Dante, one of my favourites. It features a fictional version of Nick who comes across an allegedly authentic manuscript of Dante’s The Divine Comedy.”

Silent Highway by Anthony Howell

“Anthony is my oldest friend, he’s beautiful. He went to the Quaker School that was next door to my convent. Later he became a member of the Royal Ballet company, all the time writing poetry, and eventually he couldn’t dance any more and became this great poet who also does the tango. This is an extract from his new collection. He’s got better and better. And with Silent Highway, he’s got there.“

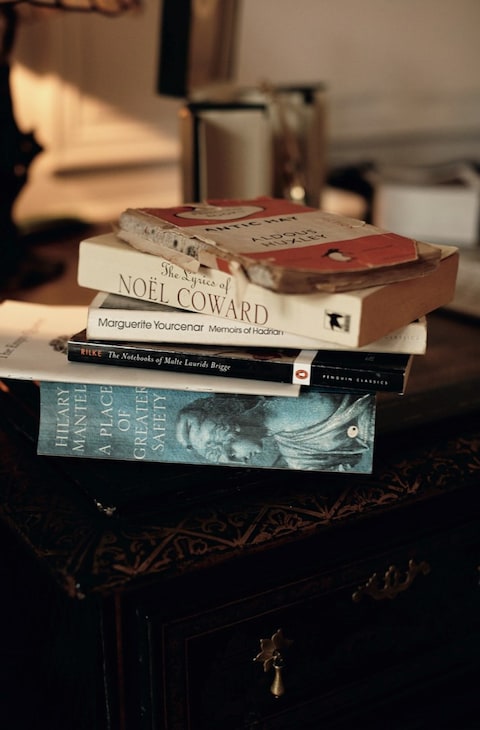

Further Reading

“At the moment I’m giving myself a course in Aldous Huxley and W.G. Sebald, neither of whom I ever properly read. I’m using Nabokov’s Speak, Memory to write with, and Coleridge, and my great, great uncle, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch [author of Venus in Furs]. As a young dancer in Berlin, my mother knew Georges Grosz and Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht – and yet she never told me anything of those people! She wanted me to grow up completely untouched by all that. She had a wonderful time in Weimar Berlin; she was bisexual, pursued by rich men, given fur coats and diamonds – didn’t want any of them, just had a ball. Then the war came, and she wanted to forget. But she read me The Jungle Book as a child. What she really liked were adventure stories – we had very different tastes. My father was the intellectual. He introduced me to Thomas De Quincey, Robert Graves, William Blake. And I was brought up on the Fattypuffs And The Thinifers (Patapoufs et Filifers in French), a children’s book by André Maurois written just after the second world war, a very anti-war piece with wonderful drawings.”

Blake, William (2007), Songs Of Innocence And Experience. Tate, London.

Burroughs, William S. (1994), The Letters Of William S. Burroughs. Penguin Books, New York.

Cave, Nick (2010), The Death Of Bunny Munro. Canongate Books, Edinburgh.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (1957), The Complete Poetical Works Of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

De Quincey, Thomas (2003), Confessions Of An English Opium-Eater. Penguin Classics, London.

Fraser, Antonia (2007), Love And Louis Xiv: The Women In The Life Of The Sun King. Anchor Books, New York.

Huxley, Aldous (2004), Antic Hay. Vintage Classics, London.

Kipling, Rudyard (2014), The Jungle Book. Macmillan Children’s Books, London.

Larkin, Philip (2003), Philip Larkin: Collected Poems. Faber & Faber, London.

Maurois, André (2000), Fattypuffs And The Thinifers. Jane Nissen Books, London.

Milton, John (2003), Paradise Lost. Penguin Classics, London.

Mosley, Charlotte (1994), Love From Nancy: The Letters Of Nancy Mitford. Sceptre, London.

Nabokov, Vladimir (2000), Speak, Memory. Penguin Classics, London.

Ono, Yoko (2013), Acorn. Or Books, New York.

Poe, Edgar Allan (2008), The Complete Poetry Of Edgar Allan Poe. Signet Classics, New York.

Rilke, Rainer Maria (1987), Sonnets To Orpheus. Wesleyan University Press, Middletown.

Sebald, W.G. (1997), The Emigrants. New Directions, New York.

Shakespeare, William (2005), The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Southern, Terry (1997), Blue Movie. Grove Press, New York.

Tart, Donna (2013), The Goldfinch. Little, Brown, London.

Tosches, Nick (2000), The Nick Tosches Reader. Da Capo, Cambridge.

Von Sacher-Masoch, Leopold (2012), (German Language), Don Juan Von Kolomea. Tredition Classics, Hamburg.

Wilde, Oscar (2010), The Ballad Of Reading Gaol And Other Poems. Penguin Classics, London.

Wyatt, Thomas (2012), The Heart’s Forest. Faber & Faber, London.

Yourcenar, Marguerite (2000), Memoirs Of Hadrian. Penguin Classics, London.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Ahead of the release of a new documentary about the late singer and actress, we return to the pages of the Spring/Summer 2015 issue, where the inimitable artist shared her most treasured texts

This story is taken from the Spring/Summer 2015 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Imagine the following a salon of sorts, with Marianne Faithfull in the chair. You have to keep up, with Marianne. She’s fiercely well-read, steeped in and fuelled by an exuberant, riotous love of literature. Discussing those decadent writer heroes of hers – Oscar Wilde, Baudelaire – she has a lovely knack of making you feel as if they’re old friends who might drop by at any moment, rather than brittle names chiselled into stone in Père Lachaise or Montparnasse cemeteries. Her conversation skips across time and geography, from Weimar Berlin to Shelley to The Jungle Book to Mick Jagger’s old love letters.

We met Marianne in a London hotel room when she was mid-way through her 50th anniversary tour. Over the evening – alternating between sipping tea and an e-cigarette – she conjured enough ideas to fill the Document twice over. Which is not to say she hasn’t got definite tastes; some authors were dismissed as “total shit”, at the mention of others she looked like she’d swallowed a light bulb and reeled off verses in a reverie. A few weeks later we visited her Paris apartment to shoot the photographs featured here. Her rooms are an Aladdin’s cave of mementos and talismans from a life worthy of fiction, a life Wilde or Rimbaud would have approved of. On the walls were newspaper clippings from the infamous Redlands bust (“girl in a fur-skin rug”), photographs of William Burroughs, sketches by her rock ‘n’ roll partner in crime, Anita Pallenberg, and books, hundreds of well-thumbed books jostling for space on her shelves.

Marianne’s original plan for this Document was to focus on English literature, in a vain attempt to narrow down her sweeping, kaleidoscopic knowledge into these 32 pages. But soon she was discussing her friends – Nick Cave, Gregory Corso – and the selection inevitably widened into this snapshot – by no means definitive – of writers whose words she holds close to her heart. Those that made it in: Charles Baudelaire, Nick Cave, Gregory Corso, Anthony Howell, Hilary Mantel, Frank McGuinness, Nick Tosches and Oscar Wilde. There were so many more we didn’t have room for; some are listed as Further Reading, which includes many authors Marianne first discovered as a teenage convent girl. When the nuns gave her the Index, the Catholic Church’s list of forbidden books, it changed her life in a way they certainly didn’t intend. She decided to read every single one of those “heretical” texts, an appropriate training in decadence for her life to come. “It was a good place to start …” she says.

Late Victorian Holocaust by Nick Cave

“Nick wrote this song for me. He said Late Victorian Holocaust was about a girl getting up to mischief in London. I think that sums it up! Being very young, very silly, very naughty and very sad. It’s wonderful. I don’t think of lyrics as poetry. To me lyrics are lyrics and poetry is poetry, they’re quite separate. The only person who’s close is Nick Cave.”

Bomb by Gregory Corso

“Gregory was my favourite. He was the naughtiest. He was impossible, but so sweet and very good-looking. He really is the greatest poet I think, even though Allen is wonderful of course, and Burroughs. I met Gregory at the Beat Hotel, at 9 rue Git-le-Coeur in Paris, where he wrote Bomb. He was on Brompton mixture at the time, which is half heroin, half cocaine, a liquid they give to cancer patients. So I didn’t really ‘meet’ Gregory then exactly, he was comatose. Occasionally he would wake up, take some more Brompton mixture and go out again.

“As a young man Gregory spent a lot of time in jail, he was a hellraiser. When he got out of jail and met Allen Ginsberg, he showed Al what he’d written, and Al said, “You’re a poet. That’s it, you’re the next Shelley.” And he was. What Allen and I knew was that as long as Gregory had a little room, rather like a cell, with just a typewriter, a bit of food, no alcohol, and no company, he would work, he would write beautiful, beautiful things. So strange how awful things can help you – he was quite happy in a small space with books and a typewriter and an idea. He didn’t even need a view. That was how he wrote. But when he went out socialising, he would get drunk. And then he was impossible. But what could you do?

“You couldn’t stop Gregory. Allen tried. He was a bit in love with Gregory. Everyone was a bit in love with Gregory. And Gregory was a bit in love with me, too.”

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

“From the corner of the divan of Persian saddle-bags on which he was lying, smoking, as was his custom, innumerable opium-tainted cigarettes …” The Picture Of Dorian Gray was the first really decadent book I read; I read it very young and it changed my life. It was all uphill after that. What I know, and what I hope you know too, is that to be decadent is not to mean that you need to smoke opium-tainted cigarettes; it’s a state of mind, and Oscar had it. My favourite story about Oscar: When he was in Paris he met Paul Claudel, a great and very well-known dramatist and poet – everyone worshipped him at the time. He was devoutly Catholic and of course believed in God, and not Oscar. They would meet at parties, and disagree. When Oscar died, Claudel received a telegram the next day which read: “God does not exist. Oscar.” Even dying, Oscar had worked out how to deal with Paul Claudel! Naughty Oscar. He had to have the last word. Poor Claudel must have been hopping.“

Paris Spleen by Charles Baudelaire

“I first read Baudelaire when I was about 14 or 15: just perfect for corruption. At the convent we were given a list called the Index, all the forbidden books of literature, banned by the Catholic Church. On the Index is all the great literature of the world, going right back to Petronius, Le Rouge et le Noir, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Oscar Wilde … everything you could think of is on the Catholic Index. I remember we had a week’s retreat with a Jesuit priest and so my friend Sally Oldfield and I decided to put ourselves through a long, long training of reading everything on the list, and we nearly did. All the forbidden books of history. It was a good start …”

The Last Days of Mankind by Frank McGuinness

“I lived in Ireland for 15 years. In 1991, I played Pirate Jenny in The Threepenny Opera in Dublin, adapted from Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Will’s original by the playwright and poet Frank McGuinness. Frank’s from Buncrana in County Donegal. As he did the translation, he obviously had to approve of me playing Pirate Jenny, so he came up to Shell Cottage where I lived, and we had a wonderful time. We’ve worked a lot together over the years: he wrote, or helped me write, Sleep, The Wedding, After The Ceasefire, and The Old House on my record Horses and High Heels. When I can’t write and I get a block, I get hold of Frank. He does the job. I sit there reading the Daily Mirror with my feet up. I’ve got this theory that if you’re in the room, you help write the song. Not all musicians agree with me, but Frank does.

“The following piece came out of us wanting to do a song cycle together: I had been reading Karl Kraus – Kraus was a great writer. He had a really hip magazine in Vienna called Die Fackel, which translates as ‘The Torch’. He was Jewish, and he was appalled by the first world war. In 1919 he published a play, The Last Days Of Mankind, in a series of special Die Fackel issues. The play was three days long – not an easy production! It came from what he’d seen during the first world war and what he saw coming in the future, which made it very interesting for Frank and for me. Frank wrote the following translation of The Last Days Of Mankind, which was going to be a song, but we never managed to get it together. But I think it’s absolutely wonderful.”

A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel

“The first half of A Place of Greater Safety, about the French Revolution, is genius. The great characters in this book are Georges-Jacques Danton and Camille Desmoulins. “A la lanterne!” It was Camille who thought of that slogan. The French Revolution was a favourite subject of the Romantic poets and one of the things I love about living in Paris. I think you have to treat people differently here, because of the revolution. If you get into a taxi or go into a shop or do any kind of transaction in Paris, you have to say, “Bonjour Monsieur” or “Bonsoir Madame.” You can’t just do as they do in New York: “Take me to 42nd Street!” It doesn’t work. You have to treat people first as human beings and then as their job. This book was the first Hilary Mantel I read, and it turned me on to all her others.”

Manifesto: Woman and Painting by Marlene Dumas

“A few years ago, I curated an exhibition for the Tate Liverpool with John Dunbar, my first husband, who is a very good artist himself. It was fantastic fun. They gave me the whole of the Tate catalogue to play with, and I found a painting in the archives by Marlene Dumas of Ulrike Meinhof (co-founder of the Red Army Faction) lying dead on the prison floor in Stuttgart – a brilliant picture, which I put in the exhibition. That was the first I knew anything about Marlene at all. Two years later, I discovered that she had done a portrait of me. The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam explained they were doing a big Marlene retrospective and were showing my portrait. I went and met Marlene there, and I sang Broken English for her. This is her 1993 piece Woman and Painting, and the portrait, which hangs in my home.”

In the Hand of Dante by Nick Tosches

“My God, I’m a fan of Nick Tosches! I adore him. These extracts are from his novel In the Hand of Dante, one of my favourites. It features a fictional version of Nick who comes across an allegedly authentic manuscript of Dante’s The Divine Comedy.”

Silent Highway by Anthony Howell

“Anthony is my oldest friend, he’s beautiful. He went to the Quaker School that was next door to my convent. Later he became a member of the Royal Ballet company, all the time writing poetry, and eventually he couldn’t dance any more and became this great poet who also does the tango. This is an extract from his new collection. He’s got better and better. And with Silent Highway, he’s got there.“

Further Reading

“At the moment I’m giving myself a course in Aldous Huxley and W.G. Sebald, neither of whom I ever properly read. I’m using Nabokov’s Speak, Memory to write with, and Coleridge, and my great, great uncle, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch [author of Venus in Furs]. As a young dancer in Berlin, my mother knew Georges Grosz and Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht – and yet she never told me anything of those people! She wanted me to grow up completely untouched by all that. She had a wonderful time in Weimar Berlin; she was bisexual, pursued by rich men, given fur coats and diamonds – didn’t want any of them, just had a ball. Then the war came, and she wanted to forget. But she read me The Jungle Book as a child. What she really liked were adventure stories – we had very different tastes. My father was the intellectual. He introduced me to Thomas De Quincey, Robert Graves, William Blake. And I was brought up on the Fattypuffs And The Thinifers (Patapoufs et Filifers in French), a children’s book by André Maurois written just after the second world war, a very anti-war piece with wonderful drawings.”

Blake, William (2007), Songs Of Innocence And Experience. Tate, London.

Burroughs, William S. (1994), The Letters Of William S. Burroughs. Penguin Books, New York.

Cave, Nick (2010), The Death Of Bunny Munro. Canongate Books, Edinburgh.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (1957), The Complete Poetical Works Of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

De Quincey, Thomas (2003), Confessions Of An English Opium-Eater. Penguin Classics, London.

Fraser, Antonia (2007), Love And Louis Xiv: The Women In The Life Of The Sun King. Anchor Books, New York.

Huxley, Aldous (2004), Antic Hay. Vintage Classics, London.

Kipling, Rudyard (2014), The Jungle Book. Macmillan Children’s Books, London.

Larkin, Philip (2003), Philip Larkin: Collected Poems. Faber & Faber, London.

Maurois, André (2000), Fattypuffs And The Thinifers. Jane Nissen Books, London.

Milton, John (2003), Paradise Lost. Penguin Classics, London.

Mosley, Charlotte (1994), Love From Nancy: The Letters Of Nancy Mitford. Sceptre, London.

Nabokov, Vladimir (2000), Speak, Memory. Penguin Classics, London.

Ono, Yoko (2013), Acorn. Or Books, New York.

Poe, Edgar Allan (2008), The Complete Poetry Of Edgar Allan Poe. Signet Classics, New York.

Rilke, Rainer Maria (1987), Sonnets To Orpheus. Wesleyan University Press, Middletown.

Sebald, W.G. (1997), The Emigrants. New Directions, New York.

Shakespeare, William (2005), The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Southern, Terry (1997), Blue Movie. Grove Press, New York.

Tart, Donna (2013), The Goldfinch. Little, Brown, London.

Tosches, Nick (2000), The Nick Tosches Reader. Da Capo, Cambridge.

Von Sacher-Masoch, Leopold (2012), (German Language), Don Juan Von Kolomea. Tredition Classics, Hamburg.

Wilde, Oscar (2010), The Ballad Of Reading Gaol And Other Poems. Penguin Classics, London.

Wyatt, Thomas (2012), The Heart’s Forest. Faber & Faber, London.

Yourcenar, Marguerite (2000), Memoirs Of Hadrian. Penguin Classics, London.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.