Rewrite

As the newest name on the BFC’s Newgen schedule, Oscar Ouyang unveils his Autumn/Winter 2025 campaign exclusively with AnOther: a world of mossy knits, coded symbols and softness with intent

- Who is it? Oscar Ouyang is a Central Saint Martins graduate specialising in knitwear, and the newest name on the BFC’s Newgen schedule

- Why do I want it? Texturally rich pieces inspired by Studio Ghibli films and the clothing real people wear

- Where can I find it? At Garden, Baby’s All Right, Blend Market, Palette de Art, Labelhood, Roadsign, Empty, Opener as well as Dover Street Market London, Paris, New York and Ginza

Who is it? Oscar Ouyang’s work is quietly maximal – rich with detail, layered symbolism and always, somehow, grounded. Fair Isle jumpers are woven with motifs borrowed from 15th-century Italian manuscripts. Botanical appliqué recalls the swelling, humid flora of Southeast Asia. Some pieces seem to sprout or grow across the shoulders like moss on stone. Others have a cinematic stillness, which owes more to Studio Ghibli than to fashion history. “I create imaginary worlds,” he says.

Since graduating from Central Saint Martins (Ouyang completed a BA in fashion design with knitwear in 2020, followed by an MA in fashion with a knitwear specialisation in 2023), he has built a practice rooted in material storytelling. Ouyang constructs garments from the thread up, using discontinued knitting machines, letting texture guide form. The process is slow, sometimes stubborn, but that’s part of the point. It’s a way of resisting ease and repetition in a fashion landscape where menswear, in particular, “can be so derivative”. Knitwear, on the other hand, he says, still has room for surprise.

That approach was formally recognised earlier this year when Ouyang was awarded a place on the British Fashion Council’s Newgen programme – a mentorship and funding scheme for emerging designers, and a platform at London Fashion Week. But with stockists across the US, Asia and Europe, Ouyang has also shown a clear instinct for how to translate creative vision into commercial reach, without compromising the integrity of his work.

Ouyang grew up in Beijing’s Haidian district, a neighbourhood known for its academic intensity, where creativity was encouraged as long as it stayed within boundaries. His childhood was filled with structured lessons: piano, violin, art. But “if you said you wanted to be an artist, they’d say, ‘No, no – that’s just a hobby,” he says. Still, he drew. While other boys played football, Ouyang stayed indoors sketching clothes onto paper dolls, not just dressing them but imagining the lives they might lead. “I was plotting my escape since I was a kid,” he says. The escape, when it came, wasn’t abrupt. By the time his parents began pulling back their support – less art classes, no more supplies – his direction was already set.

At Central Saint Martins, he found a different kind of creative pressure. “They throw everyone together like a cocktail, and see what comes out,” he says. That intensity pushed him to find a point of difference, and in doing so, to identify what was already his. “It wasn’t about being super chic. That wasn’t my strong suit then. But storytelling through texture? That was mine.”

Why do I want it? That narrative instinct has matured for Ouyang’s Autumn/Winter 2025 collection, which feels like a considered expansion of the world he introduced during his MA. “It’s a continuation, inspired by Studio Ghibli,” he says. “But translated into modern fashion.” The result is not costume or fantasy for its own sake, but clothing with a quiet charge – pieces that are functional, wearable, and full of meaning if you know where to look. “A lot of our references come from street photography – people like Chris Killip, Helmut Newton, Jeff Wall, even newer names like Thomas Rousset or Wolfgang Tillmans,” Ouyang explains. “We look at real people and how they dress. The storytelling element is more from animation and games. Zelda, that kind of thing.”

His Fair Isle knits reflect that sensibility, replacing traditional motifs with talismanic symbols: swords, shells, scabbards. “We had a lot of leftover yarn from an Italian mill that donated during my MA,” Ouyang says. “So we asked, what can we do with this? That’s when we started designing the pattern – our version of a print.” That print was shaped in part by a historical discovery. “We came across [Florio Vavassore] while looking through the Met’s digital library,” he says. “They scan all these old manuscripts and fashion exhibitions in high resolution. His work had these pixelated leafy patterns that translated beautifully into knit. When you’re designing knitwear, you have to work within technical limits – like a punch card with 24 or 60 stitches per repeat. His visuals just worked perfectly within that.”

There’s a quiet toughness in these clothes, a sense of armour hidden within softness. “London can be a dodgy place,” Ouyang says. “Dressing can be a form of self-protection. Especially as a queer person, you sometimes dress to be invisible. This collection plays with that.” But not everything is defensive. A white cashmere coat with an alpaca collar is cut to keep warmth close without bulk. A shearling-edged wool balaclava, sculpted into a mohawk, feels at once playful and deliberate.

Military elements stipple the collection, but they’re refracted through a Japanese lens. “In Asia, we don’t really have that traditional British workwear influence – unless you work in finance and wear a suit,” Ouyang says. Instead, his nods to utility come shaped by Japanese designers like Jun Takahashi and Number (N)ine, where structure meets irregularity, and garments carry a quiet charge. A knee-length coat in wool bouclé echoes tactical outerwear in its weight and wrap. As always, there’s a kind of camouflage at play: clothes that protect, conceal or declare, depending on how you choose to wear them.

Texture is paramount throughout. The yarns are sourced from Mongolia – yak, cashmere, alpaca – selected for the way they feel against the skin. “We’re in that mid to high price tier, and I think if someone’s paying close to £1,000 for a coat, it should feel like it,” he says. Most people still discover the label through touch – on a rail at Dover Street Market, in a boutique in Seoul or Tokyo – so the finish matters. If a sleeve doesn’t register as something to be worn, kept, and remembered, the spell breaks. And increasingly, he’s not interested in the one-off. At CSM, he says, there was pressure to go maximal. Now he’s more interested in what people want to wear again and again: “I want a niche, but also something practical and desirable.”

This collection delivers both. Its softness is purposeful, with a bite, and its symbolism doesn’t need explanation. “It’s not an aggressive collection,” Ouyang says. “It’s subtle – more about texture and atmosphere.”

Where can I find it? At Garden, Baby’s All Right, Blend Market, Palette de Art, Labelhood, Roadsign, Empty, Opener as well as Dover Street Market London, Paris and Ginza.

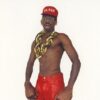

Photographer: Josie Hall at MMXX. Stylist and Consultant: Jack Collins. Casting: Najia Li Saad at Huxley. Make-up: Porsche Poon at Total Management. Hair: Yoko Setoyama at Dawes & Co. Production: MMXX. Model: Vinnie at Kate Moss Agency

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

As the newest name on the BFC’s Newgen schedule, Oscar Ouyang unveils his Autumn/Winter 2025 campaign exclusively with AnOther: a world of mossy knits, coded symbols and softness with intent

- Who is it? Oscar Ouyang is a Central Saint Martins graduate specialising in knitwear, and the newest name on the BFC’s Newgen schedule

- Why do I want it? Texturally rich pieces inspired by Studio Ghibli films and the clothing real people wear

- Where can I find it? At Garden, Baby’s All Right, Blend Market, Palette de Art, Labelhood, Roadsign, Empty, Opener as well as Dover Street Market London, Paris, New York and Ginza

Who is it? Oscar Ouyang’s work is quietly maximal – rich with detail, layered symbolism and always, somehow, grounded. Fair Isle jumpers are woven with motifs borrowed from 15th-century Italian manuscripts. Botanical appliqué recalls the swelling, humid flora of Southeast Asia. Some pieces seem to sprout or grow across the shoulders like moss on stone. Others have a cinematic stillness, which owes more to Studio Ghibli than to fashion history. “I create imaginary worlds,” he says.

Since graduating from Central Saint Martins (Ouyang completed a BA in fashion design with knitwear in 2020, followed by an MA in fashion with a knitwear specialisation in 2023), he has built a practice rooted in material storytelling. Ouyang constructs garments from the thread up, using discontinued knitting machines, letting texture guide form. The process is slow, sometimes stubborn, but that’s part of the point. It’s a way of resisting ease and repetition in a fashion landscape where menswear, in particular, “can be so derivative”. Knitwear, on the other hand, he says, still has room for surprise.

That approach was formally recognised earlier this year when Ouyang was awarded a place on the British Fashion Council’s Newgen programme – a mentorship and funding scheme for emerging designers, and a platform at London Fashion Week. But with stockists across the US, Asia and Europe, Ouyang has also shown a clear instinct for how to translate creative vision into commercial reach, without compromising the integrity of his work.

Ouyang grew up in Beijing’s Haidian district, a neighbourhood known for its academic intensity, where creativity was encouraged as long as it stayed within boundaries. His childhood was filled with structured lessons: piano, violin, art. But “if you said you wanted to be an artist, they’d say, ‘No, no – that’s just a hobby,” he says. Still, he drew. While other boys played football, Ouyang stayed indoors sketching clothes onto paper dolls, not just dressing them but imagining the lives they might lead. “I was plotting my escape since I was a kid,” he says. The escape, when it came, wasn’t abrupt. By the time his parents began pulling back their support – less art classes, no more supplies – his direction was already set.

At Central Saint Martins, he found a different kind of creative pressure. “They throw everyone together like a cocktail, and see what comes out,” he says. That intensity pushed him to find a point of difference, and in doing so, to identify what was already his. “It wasn’t about being super chic. That wasn’t my strong suit then. But storytelling through texture? That was mine.”

Why do I want it? That narrative instinct has matured for Ouyang’s Autumn/Winter 2025 collection, which feels like a considered expansion of the world he introduced during his MA. “It’s a continuation, inspired by Studio Ghibli,” he says. “But translated into modern fashion.” The result is not costume or fantasy for its own sake, but clothing with a quiet charge – pieces that are functional, wearable, and full of meaning if you know where to look. “A lot of our references come from street photography – people like Chris Killip, Helmut Newton, Jeff Wall, even newer names like Thomas Rousset or Wolfgang Tillmans,” Ouyang explains. “We look at real people and how they dress. The storytelling element is more from animation and games. Zelda, that kind of thing.”

His Fair Isle knits reflect that sensibility, replacing traditional motifs with talismanic symbols: swords, shells, scabbards. “We had a lot of leftover yarn from an Italian mill that donated during my MA,” Ouyang says. “So we asked, what can we do with this? That’s when we started designing the pattern – our version of a print.” That print was shaped in part by a historical discovery. “We came across [Florio Vavassore] while looking through the Met’s digital library,” he says. “They scan all these old manuscripts and fashion exhibitions in high resolution. His work had these pixelated leafy patterns that translated beautifully into knit. When you’re designing knitwear, you have to work within technical limits – like a punch card with 24 or 60 stitches per repeat. His visuals just worked perfectly within that.”

There’s a quiet toughness in these clothes, a sense of armour hidden within softness. “London can be a dodgy place,” Ouyang says. “Dressing can be a form of self-protection. Especially as a queer person, you sometimes dress to be invisible. This collection plays with that.” But not everything is defensive. A white cashmere coat with an alpaca collar is cut to keep warmth close without bulk. A shearling-edged wool balaclava, sculpted into a mohawk, feels at once playful and deliberate.

Military elements stipple the collection, but they’re refracted through a Japanese lens. “In Asia, we don’t really have that traditional British workwear influence – unless you work in finance and wear a suit,” Ouyang says. Instead, his nods to utility come shaped by Japanese designers like Jun Takahashi and Number (N)ine, where structure meets irregularity, and garments carry a quiet charge. A knee-length coat in wool bouclé echoes tactical outerwear in its weight and wrap. As always, there’s a kind of camouflage at play: clothes that protect, conceal or declare, depending on how you choose to wear them.

Texture is paramount throughout. The yarns are sourced from Mongolia – yak, cashmere, alpaca – selected for the way they feel against the skin. “We’re in that mid to high price tier, and I think if someone’s paying close to £1,000 for a coat, it should feel like it,” he says. Most people still discover the label through touch – on a rail at Dover Street Market, in a boutique in Seoul or Tokyo – so the finish matters. If a sleeve doesn’t register as something to be worn, kept, and remembered, the spell breaks. And increasingly, he’s not interested in the one-off. At CSM, he says, there was pressure to go maximal. Now he’s more interested in what people want to wear again and again: “I want a niche, but also something practical and desirable.”

This collection delivers both. Its softness is purposeful, with a bite, and its symbolism doesn’t need explanation. “It’s not an aggressive collection,” Ouyang says. “It’s subtle – more about texture and atmosphere.”

Where can I find it? At Garden, Baby’s All Right, Blend Market, Palette de Art, Labelhood, Roadsign, Empty, Opener as well as Dover Street Market London, Paris and Ginza.

Photographer: Josie Hall at MMXX. Stylist and Consultant: Jack Collins. Casting: Najia Li Saad at Huxley. Make-up: Porsche Poon at Total Management. Hair: Yoko Setoyama at Dawes & Co. Production: MMXX. Model: Vinnie at Kate Moss Agency

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.