Rewrite

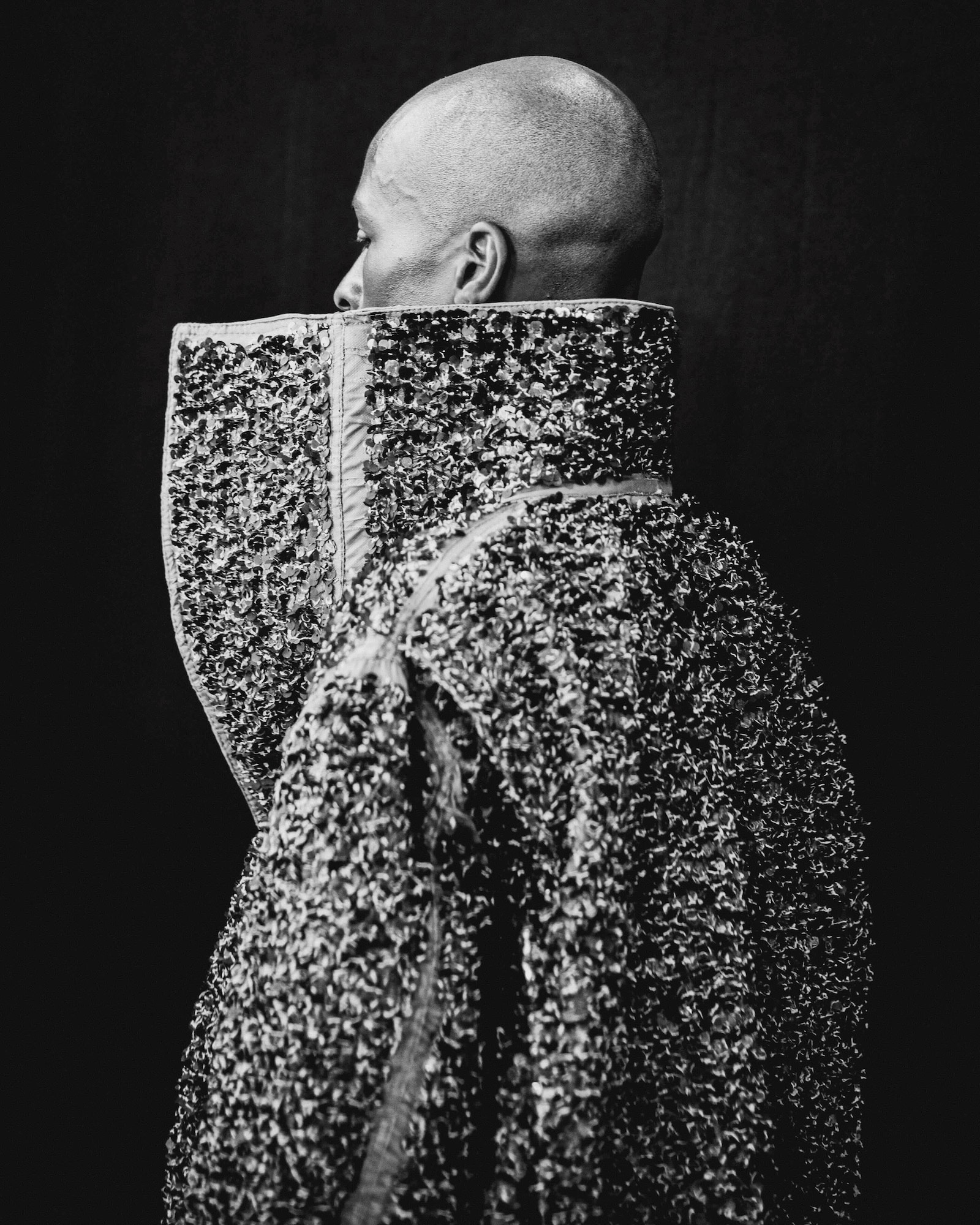

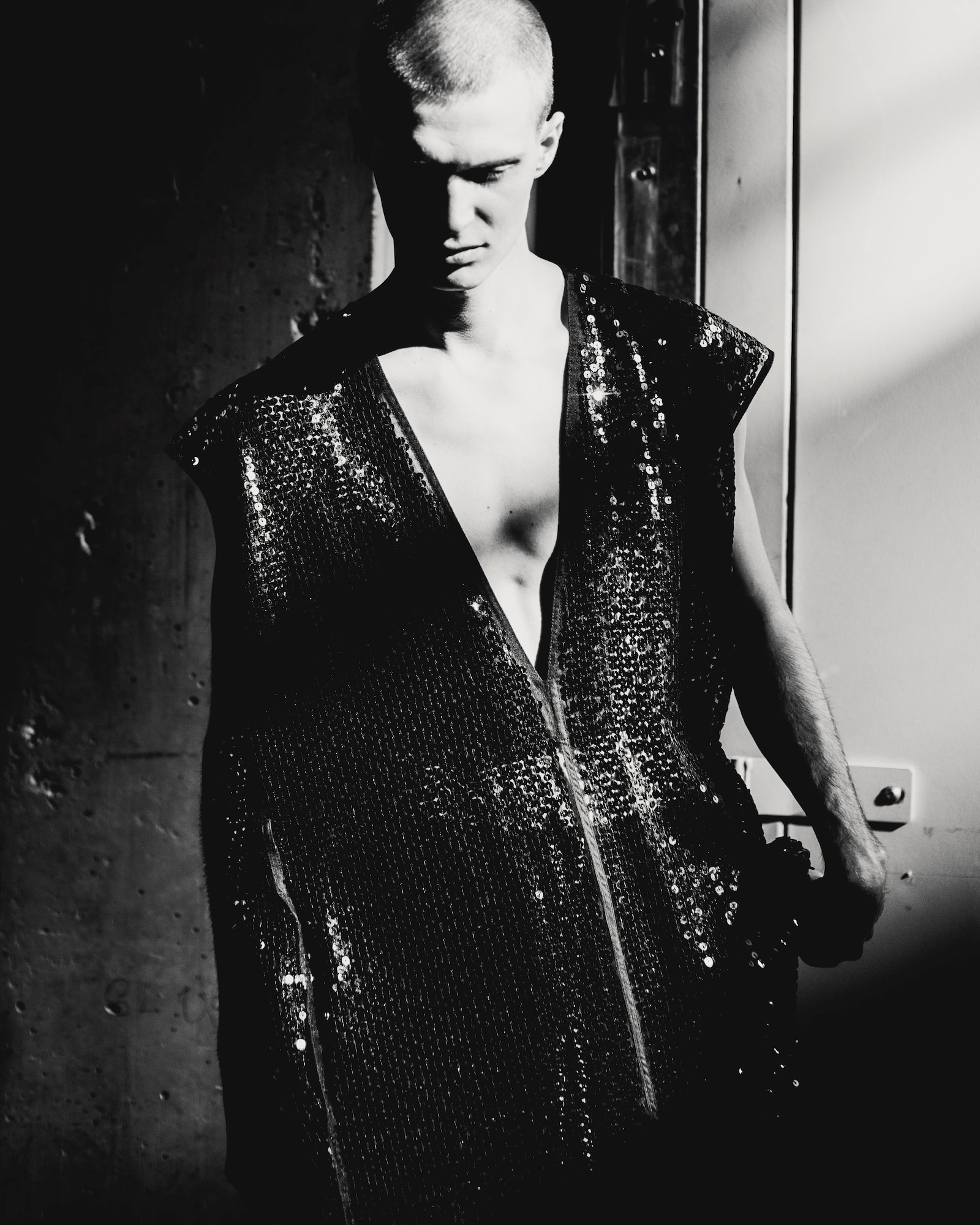

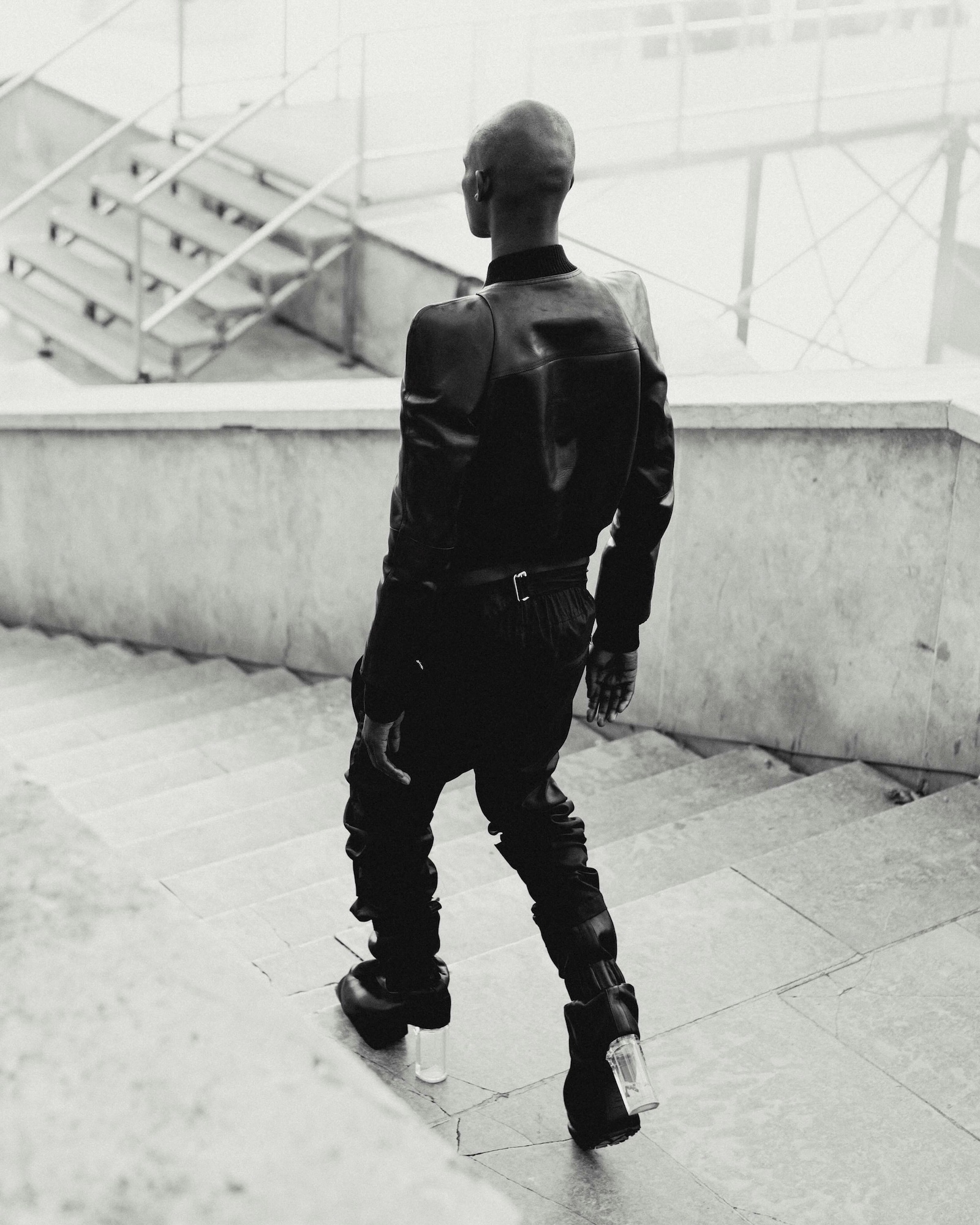

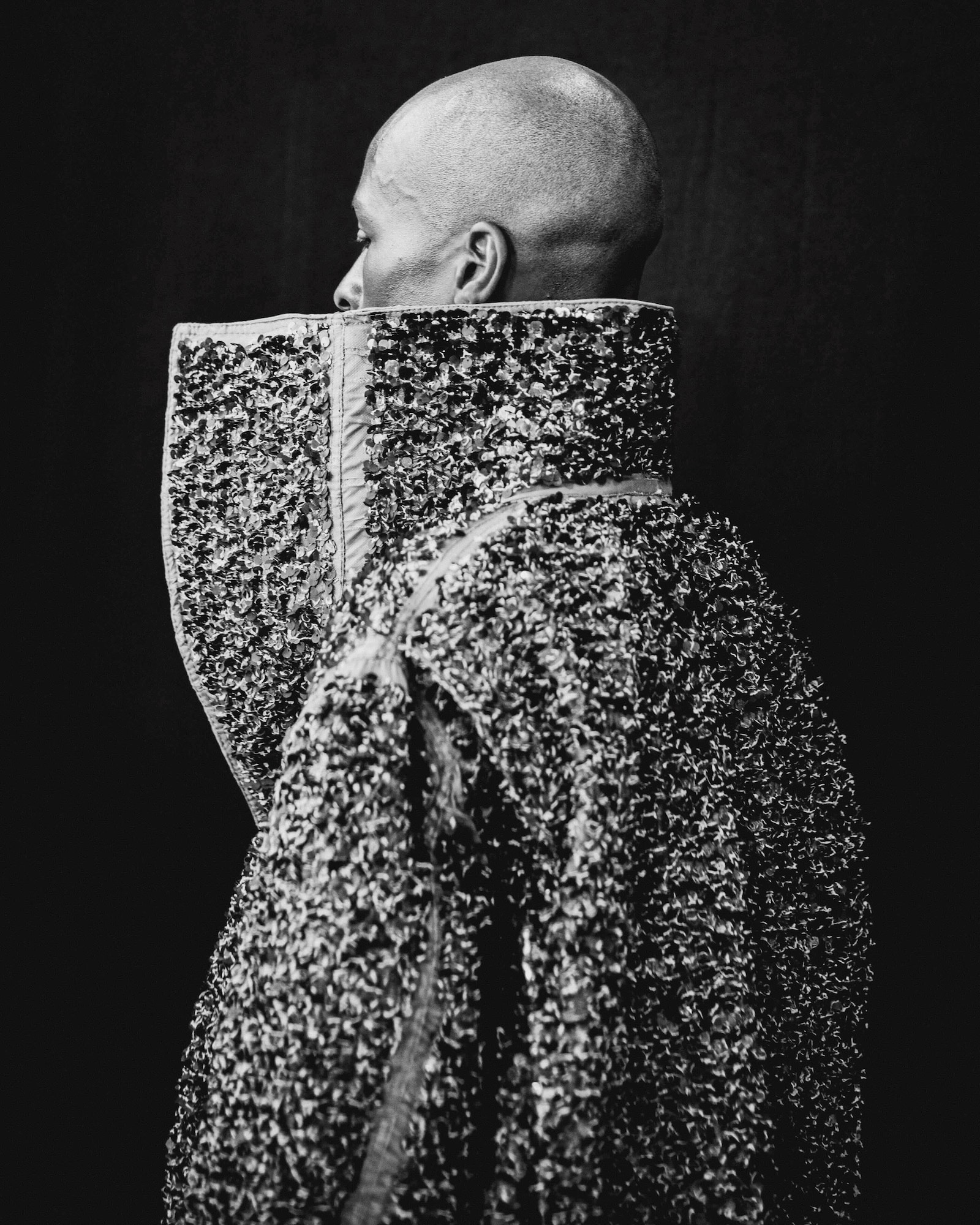

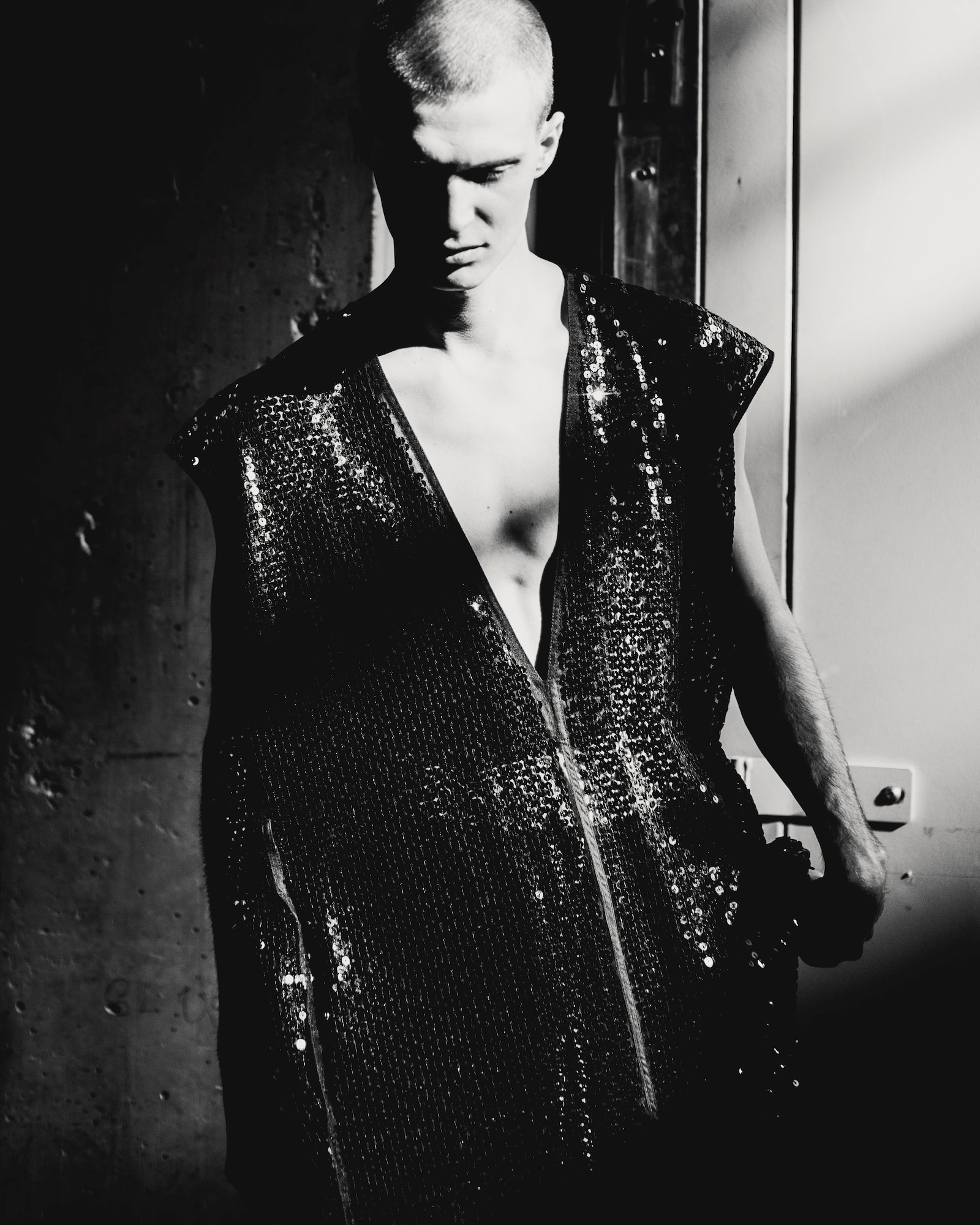

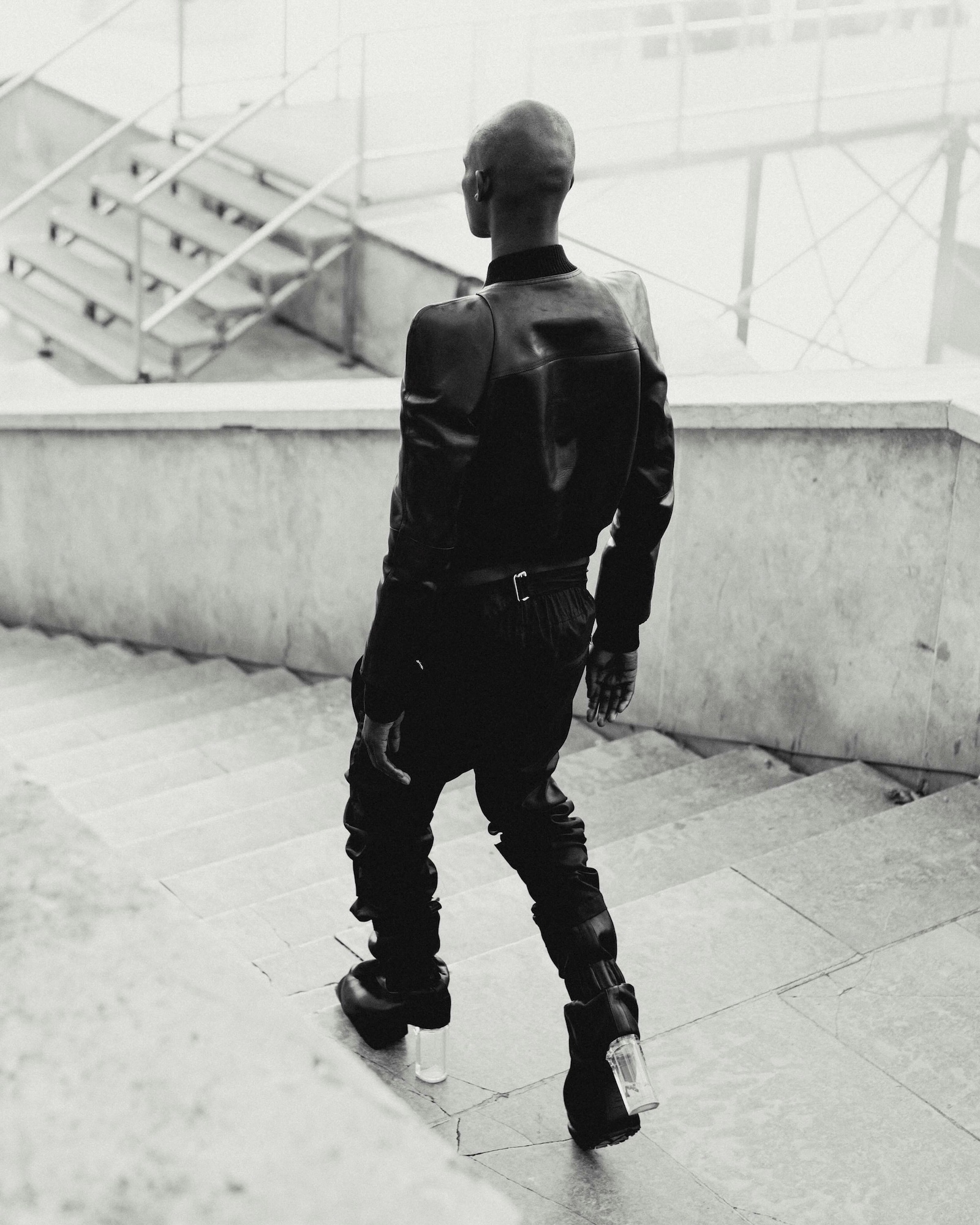

Lead ImageRick Owens Spring/Summer 2026 MenswearPhotography by Paul Phung

Rick Owens is a great designer – like, canon of the great greats, down in the history books of all-time greats. Alongside Charles James, and Marc Jacobs, and maybe outliers like Gilbert Adrian, Claire McCardell or Geoffrey Beene (love me some Beene), he’s one of the forgers of the modern identity of American fashion.

But what sometimes doesn’t come across so great in Owens’ great, great shows is how nice he is. Which is, maybe, an anodyne word – Owens is warm, passionate, affectionate, deadpan funny – but nice truly sums everything up. Owens makes you feel warm inside – as a man, for sure, and often with his clothes. They’re dark and cold on the outside, warm and fuzzy inside. They’re great.

So that’s why it makes sense that the Palais Galliera exhibition of Owens’ clothes was called Temple of Love – because you get the sense that Owens loves what he does, and that positive energy radiates from everything he creates. Sounds a bit hippy-drippy, but Owens is from California, after all. And besides, in Owens’ own words, “‘love’ is a word really worth promoting right now.” The mannequins in the show are also hiked up high, like icons on altars to be worshipped. But whether those are benevolent gods or otherwise remains to be seen – staring up at them also reminded me of Don’t Look Up, the somewhat-maligned 2021 political satire of an approaching comet that will destroy human life. Although of course, here, the only way to look was into the eye – of creation, rather than destruction.

Lots of fashion designers ignore exhibitions about their life’s work. They especially shudder at the idea of calling it ‘retrospective’ – I can’t think of any designer who has revelled in that, except maybe Yves Saint Laurent, a man so obsessed with securing his own place in destiny, he used to write “Musée” on the labels of clothes in his fashion shows he felt belonged in his self-built mausoleum of greatest hits. Morbid – quite up Rick’s rue.

“A retrospective summons up thoughts of peaking, finality and decline,” said Owens the satirist. “I was delighted to lean into that.” He even called his Spring/Summer 2026 collection ‘Temple’, after the show, and marched his audience over the museum right afterwards to bask in his glory. Indeed, if Christ expelled the traders and money-lenders from the temple, Rick Owens invited us all right back in.

But this collection was no self-indulgent, onanistic exercise in auto-reference. In the middle of the fountain of the Palais de Tokyo, under baking sun, Owens built a scaffold structure topped with a metal spire – a temple, see – and then challenged his models to scramble down the sides in his signature perspex platform heels. It made you wonder if Owens was hankering after a human sacrifice at this altar to high fashion – there was something a bit Wicker Man about the edifice, in all honesty – but luckily no models were harmed in the making of this epic fashion moment. They then began to wade knee-deep in the stagnant water, pausing once to ‘baptise’ themselves, and several thousand pounds of next-season Owens, in the murky depths.

It reminded me of the reverse of something Owens once told me, of his creative and business independence: “It’s not like I’m obligated to make any compromises, which is a wonderful thing. I probably sound a little gloaty to say that, or a little boastful, but it’s significant. I could just burn the whole fucking place down.” Or, indeed, drown it all.

Rick Owens always has the sublime confidence to allow his clothes to, sometimes, be subsumed by the theatricality of their presentation. Sometimes he scales it back, sometimes piles it on to excess – this was the latter. But he still knows they’re great. This time, for Owens, there was a sense of looking back, referencing fetishwear of the sex workers on Hollywood Boulevard, where Owens began his business in the 1990s – “the pursuit of glamour and sleaze” is how he termed it – but also a double-speak of the industrial and couture, the elegant and the bestial. Meaning an outfit could reference a slithery Madeleine Vionnet evening gown in sequinned chiffon, or sport a high-rise collar and arching cocoon-back akin to Cristobal Balenciaga, and be juxtaposed with chewed-up and shredded leathers like seventies punks. Goddesses of fashion meets Richard Hell – an unholy alliance.

Owens strung his models with straps, because he said men liked the look of them – a form of macho decoration, imbued with utility and industry, and a hint of BDSM appreciated by a smaller clique. But, in the next breath, he compared them to “garlands held by nymphs to trap a satyr in William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s sylvan neoclassical paintings.” I guess, if you squint hard enough?

So allow me a bit of poetic license myself. At the finale of Owens’ show, when his models clambered back up his tower and laid themselves out, a few dangling preciously on ledges and turrets, utilising those decorative straps to lash themselves to the construction. It reminded me of the vast, over-life-size Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault, that takes up an entire wall (just about) in the Louvre. Owens’ vision, however, is even bigger.

I called it the finale up there – nix that. Climax is much better, as fountains gushed up into the air to herald Owens’ bow. The man knows how to put on a show. Actually, this time we got two for the price of one. We came, we saw, he conquered.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageRick Owens Spring/Summer 2026 MenswearPhotography by Paul Phung

Rick Owens is a great designer – like, canon of the great greats, down in the history books of all-time greats. Alongside Charles James, and Marc Jacobs, and maybe outliers like Gilbert Adrian, Claire McCardell or Geoffrey Beene (love me some Beene), he’s one of the forgers of the modern identity of American fashion.

But what sometimes doesn’t come across so great in Owens’ great, great shows is how nice he is. Which is, maybe, an anodyne word – Owens is warm, passionate, affectionate, deadpan funny – but nice truly sums everything up. Owens makes you feel warm inside – as a man, for sure, and often with his clothes. They’re dark and cold on the outside, warm and fuzzy inside. They’re great.

So that’s why it makes sense that the Palais Galliera exhibition of Owens’ clothes was called Temple of Love – because you get the sense that Owens loves what he does, and that positive energy radiates from everything he creates. Sounds a bit hippy-drippy, but Owens is from California, after all. And besides, in Owens’ own words, “‘love’ is a word really worth promoting right now.” The mannequins in the show are also hiked up high, like icons on altars to be worshipped. But whether those are benevolent gods or otherwise remains to be seen – staring up at them also reminded me of Don’t Look Up, the somewhat-maligned 2021 political satire of an approaching comet that will destroy human life. Although of course, here, the only way to look was into the eye – of creation, rather than destruction.

Lots of fashion designers ignore exhibitions about their life’s work. They especially shudder at the idea of calling it ‘retrospective’ – I can’t think of any designer who has revelled in that, except maybe Yves Saint Laurent, a man so obsessed with securing his own place in destiny, he used to write “Musée” on the labels of clothes in his fashion shows he felt belonged in his self-built mausoleum of greatest hits. Morbid – quite up Rick’s rue.

“A retrospective summons up thoughts of peaking, finality and decline,” said Owens the satirist. “I was delighted to lean into that.” He even called his Spring/Summer 2026 collection ‘Temple’, after the show, and marched his audience over the museum right afterwards to bask in his glory. Indeed, if Christ expelled the traders and money-lenders from the temple, Rick Owens invited us all right back in.

But this collection was no self-indulgent, onanistic exercise in auto-reference. In the middle of the fountain of the Palais de Tokyo, under baking sun, Owens built a scaffold structure topped with a metal spire – a temple, see – and then challenged his models to scramble down the sides in his signature perspex platform heels. It made you wonder if Owens was hankering after a human sacrifice at this altar to high fashion – there was something a bit Wicker Man about the edifice, in all honesty – but luckily no models were harmed in the making of this epic fashion moment. They then began to wade knee-deep in the stagnant water, pausing once to ‘baptise’ themselves, and several thousand pounds of next-season Owens, in the murky depths.

It reminded me of the reverse of something Owens once told me, of his creative and business independence: “It’s not like I’m obligated to make any compromises, which is a wonderful thing. I probably sound a little gloaty to say that, or a little boastful, but it’s significant. I could just burn the whole fucking place down.” Or, indeed, drown it all.

Rick Owens always has the sublime confidence to allow his clothes to, sometimes, be subsumed by the theatricality of their presentation. Sometimes he scales it back, sometimes piles it on to excess – this was the latter. But he still knows they’re great. This time, for Owens, there was a sense of looking back, referencing fetishwear of the sex workers on Hollywood Boulevard, where Owens began his business in the 1990s – “the pursuit of glamour and sleaze” is how he termed it – but also a double-speak of the industrial and couture, the elegant and the bestial. Meaning an outfit could reference a slithery Madeleine Vionnet evening gown in sequinned chiffon, or sport a high-rise collar and arching cocoon-back akin to Cristobal Balenciaga, and be juxtaposed with chewed-up and shredded leathers like seventies punks. Goddesses of fashion meets Richard Hell – an unholy alliance.

Owens strung his models with straps, because he said men liked the look of them – a form of macho decoration, imbued with utility and industry, and a hint of BDSM appreciated by a smaller clique. But, in the next breath, he compared them to “garlands held by nymphs to trap a satyr in William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s sylvan neoclassical paintings.” I guess, if you squint hard enough?

So allow me a bit of poetic license myself. At the finale of Owens’ show, when his models clambered back up his tower and laid themselves out, a few dangling preciously on ledges and turrets, utilising those decorative straps to lash themselves to the construction. It reminded me of the vast, over-life-size Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault, that takes up an entire wall (just about) in the Louvre. Owens’ vision, however, is even bigger.

I called it the finale up there – nix that. Climax is much better, as fountains gushed up into the air to herald Owens’ bow. The man knows how to put on a show. Actually, this time we got two for the price of one. We came, we saw, he conquered.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.