Rewrite

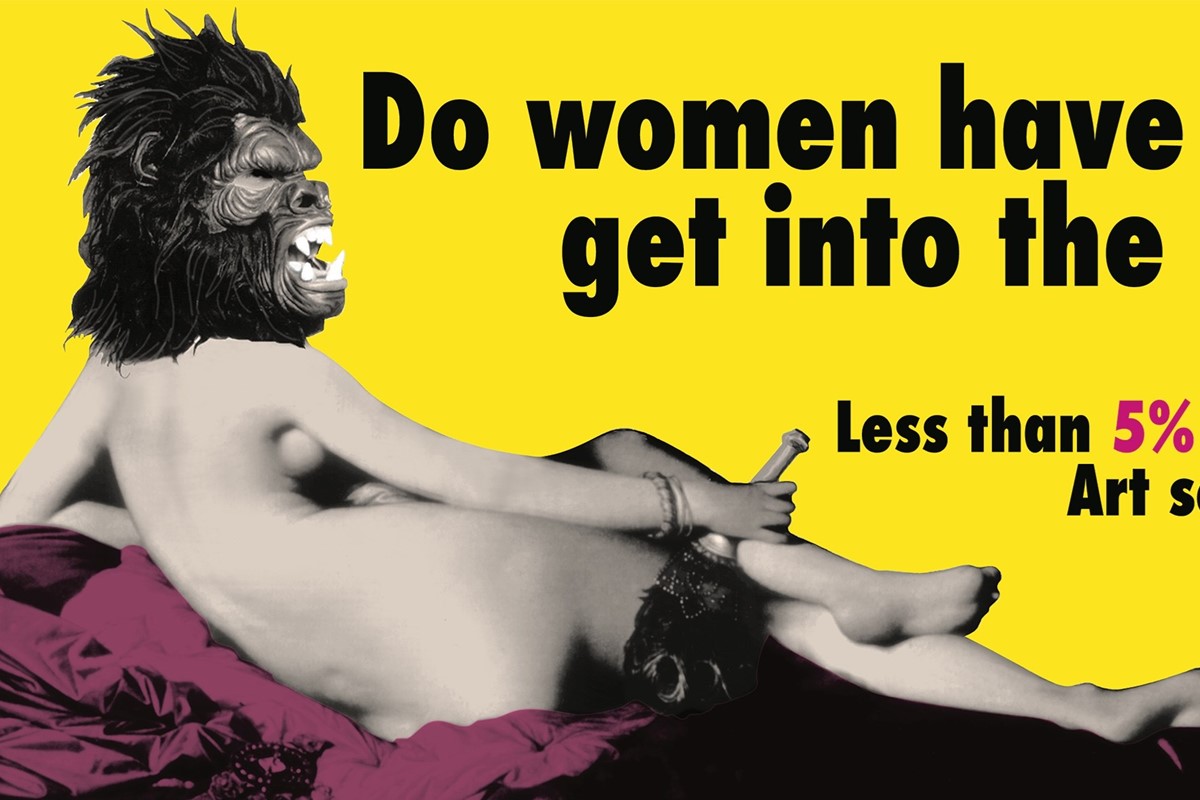

Lead ImageDo Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?, 1989Courtesy of Guerrilla Girls

As a group, the Guerrilla Girls have reached iconic status, yet their individual identities remain hidden behind identical gorilla masks (they are each anonymous and styled after high-profile women from previous generations). They got together in 1985, following a protest by women artists at MoMA which highlighted the lack of diversity in the museum’s survey show An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture.

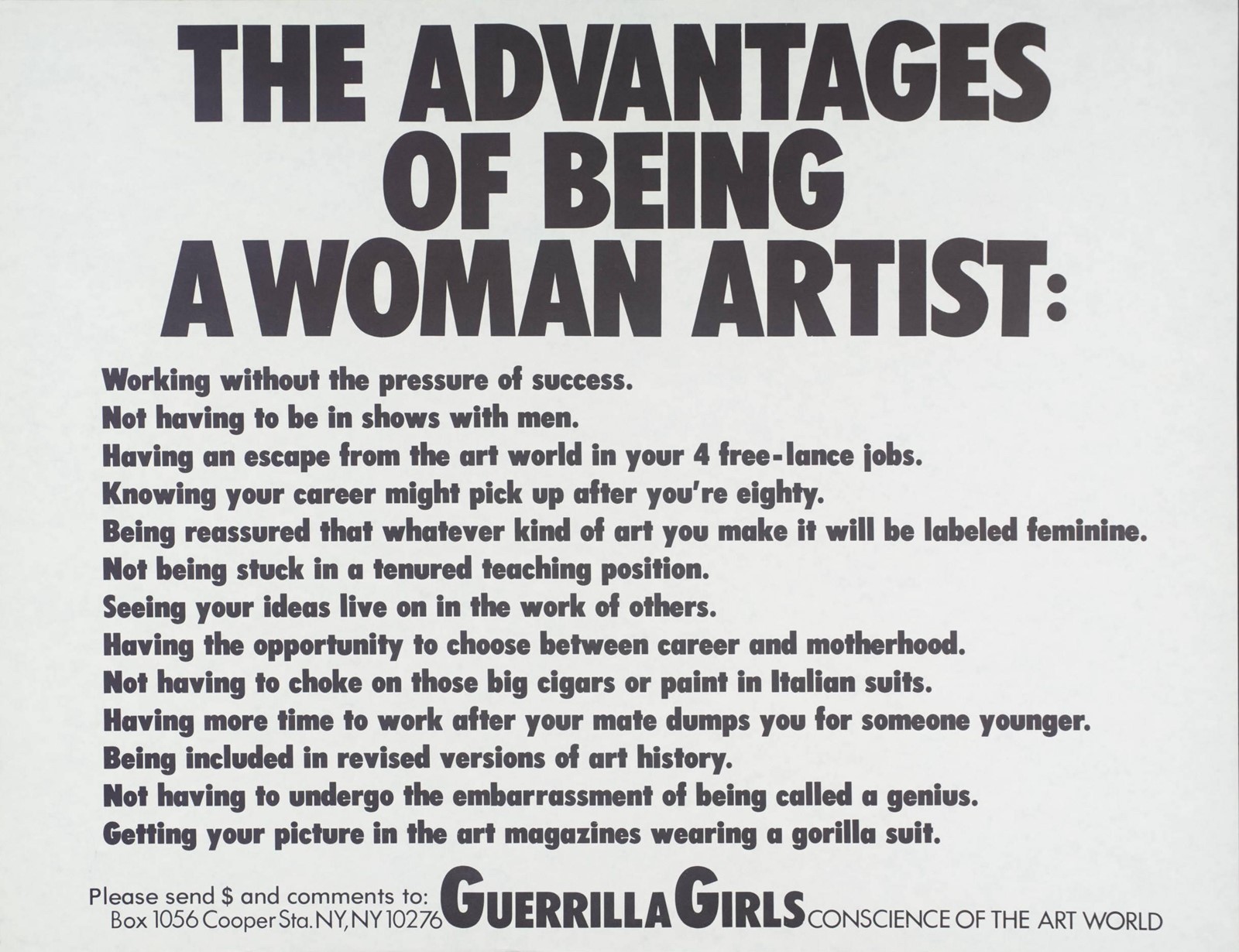

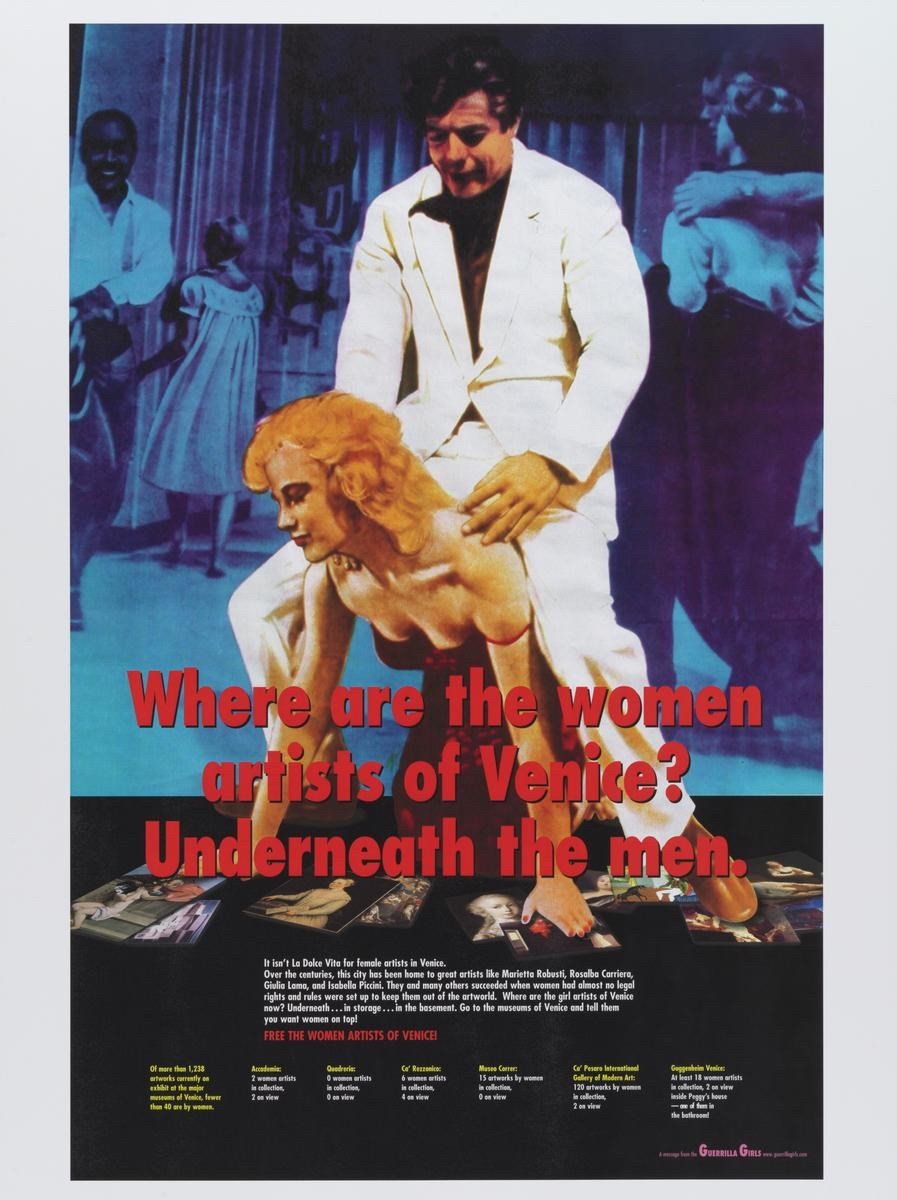

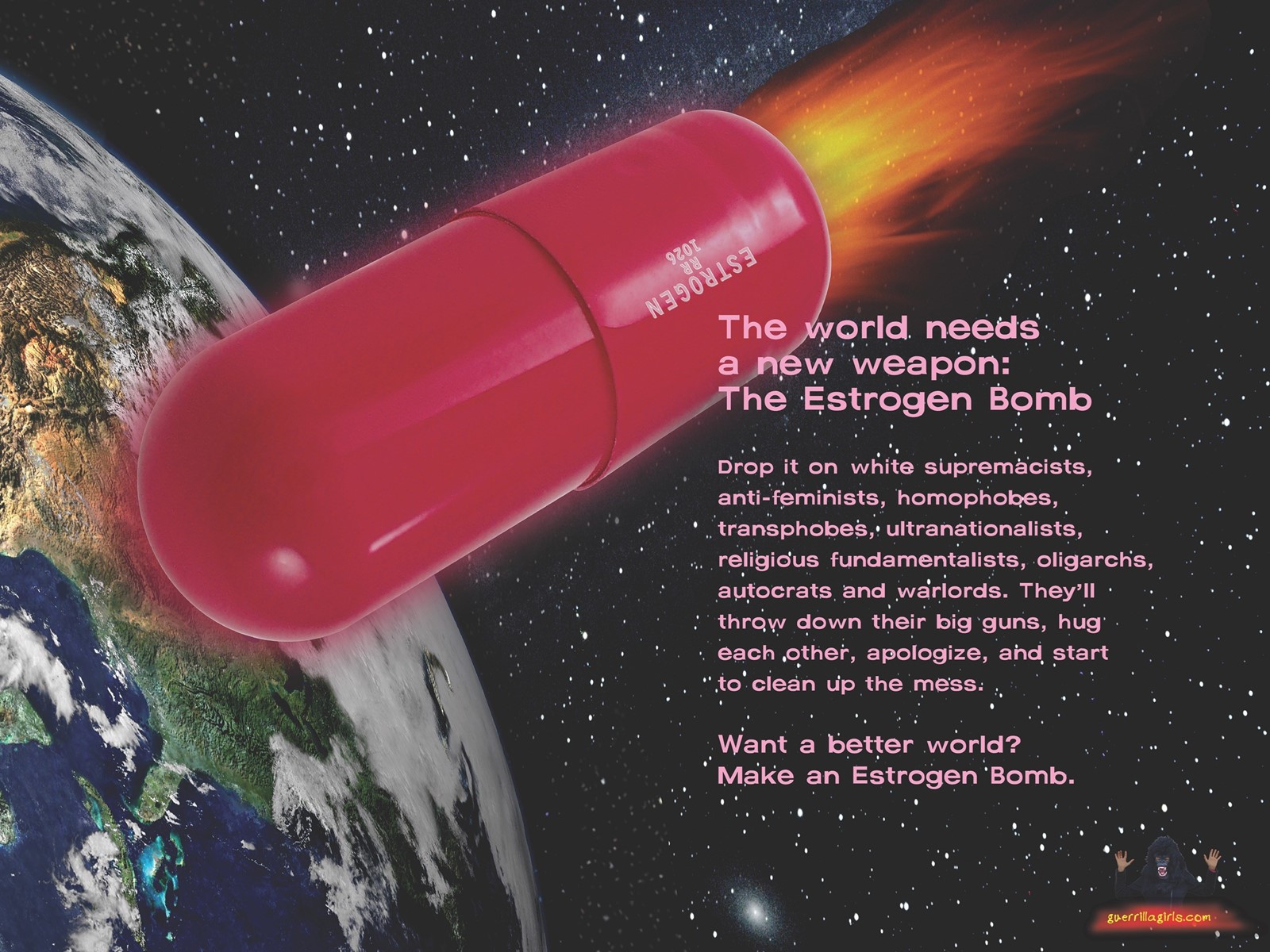

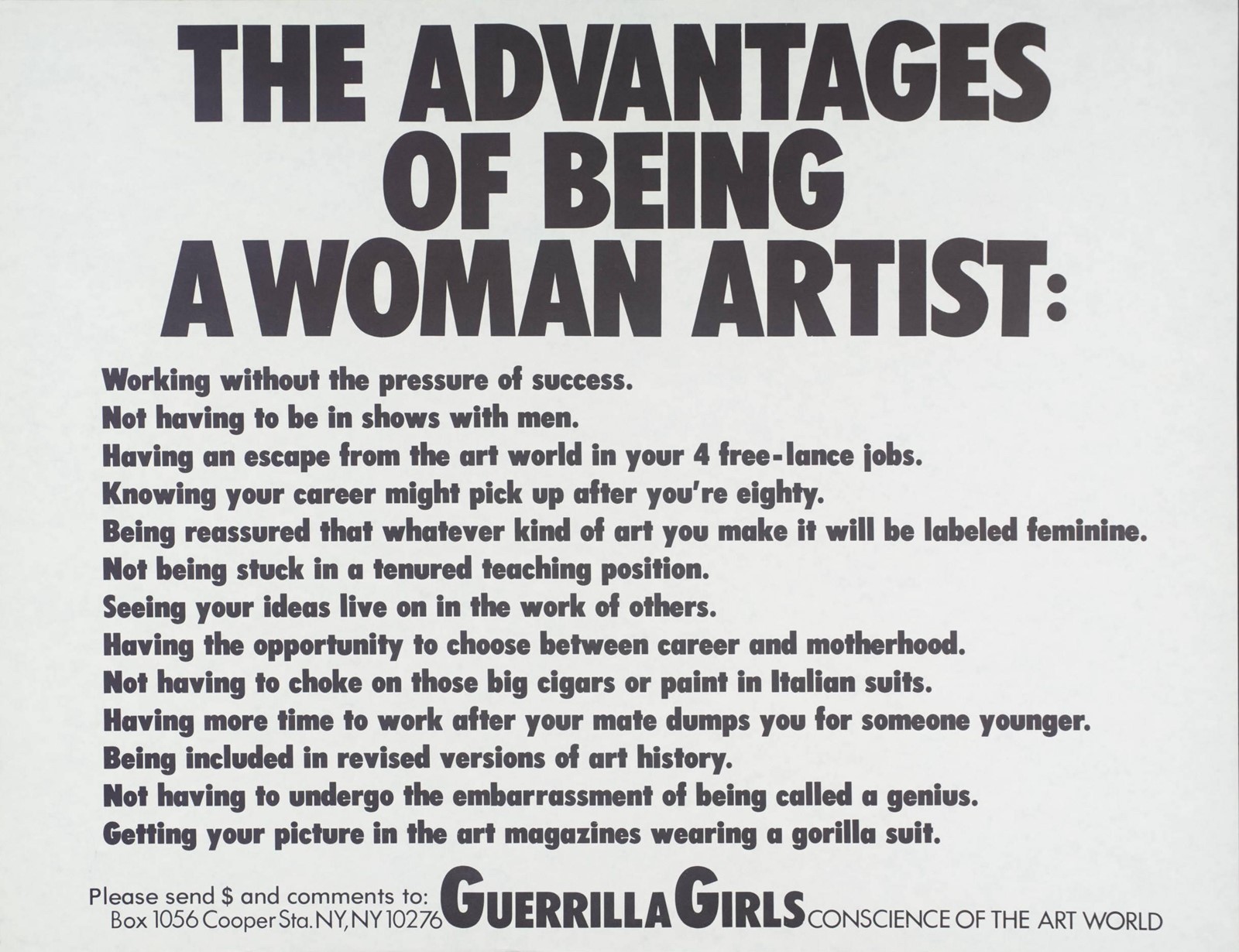

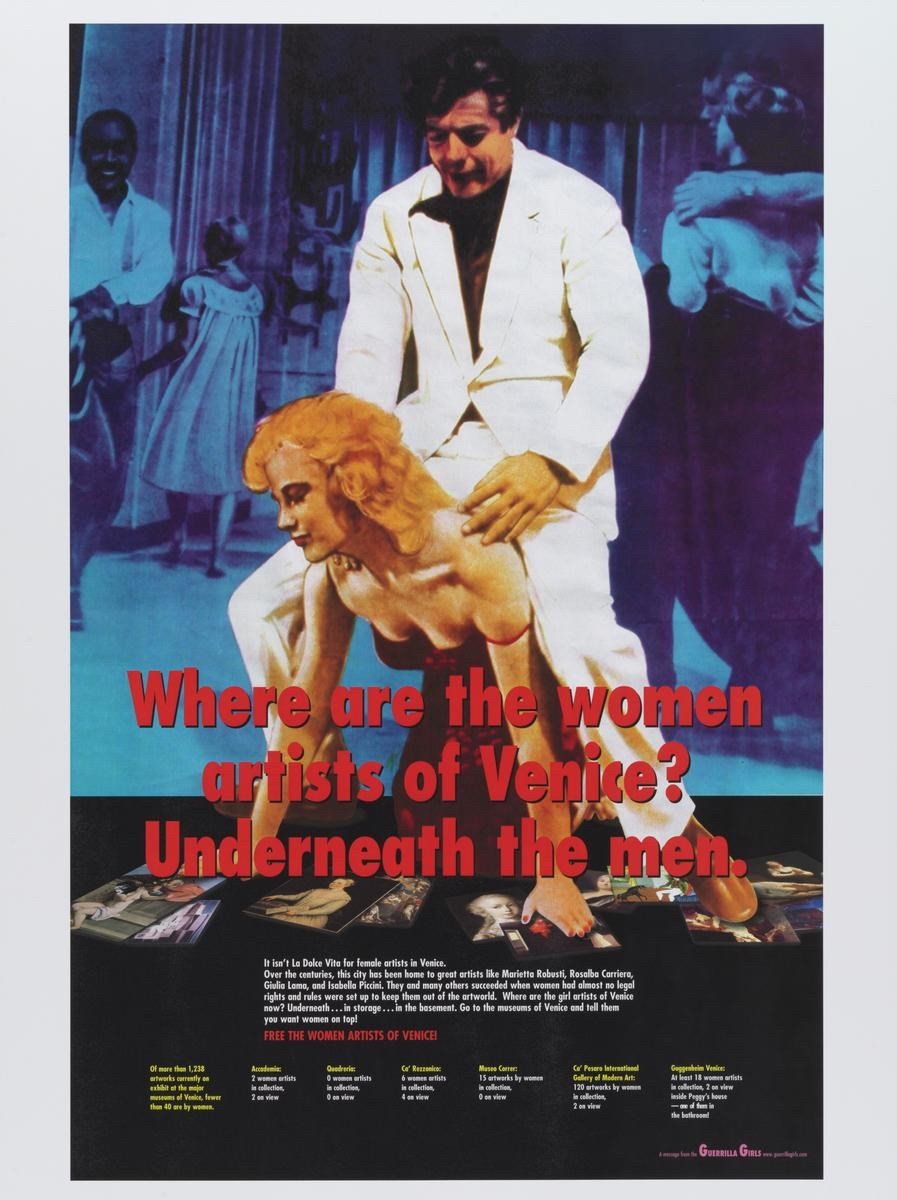

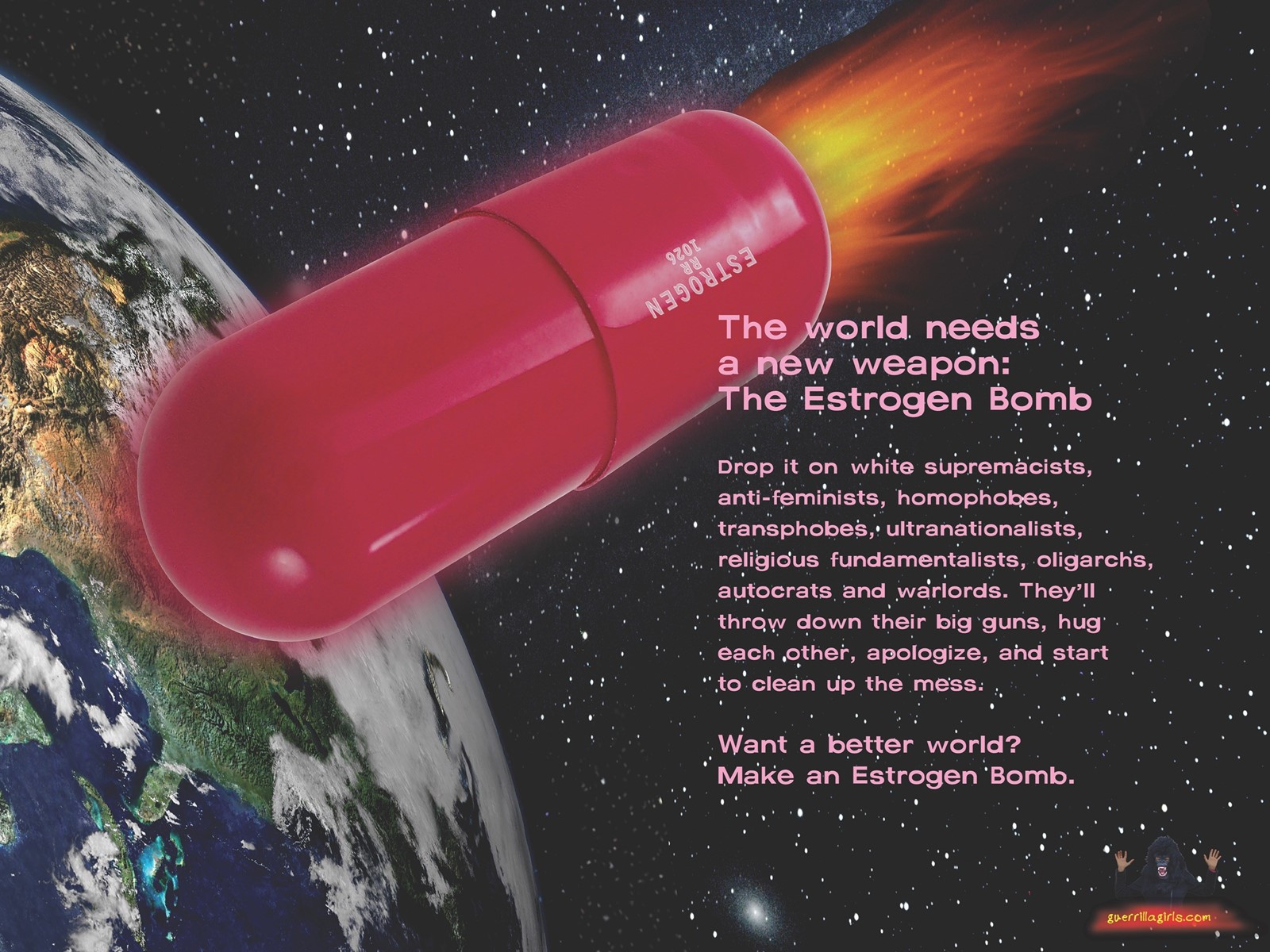

Their street posters from the early years remain instantly recognisable: black text on white backgrounds highlighting the cold stats of collections and museums that almost always sway in favour of white men. Aimed at shaking up the art establishment, these pieces called on fellow artists, curators, collectors and gallerists to take action. Since then, they’ve used their bold visuals and no-nonsense approach to talk directly about abortion, imprisonment, and Trump’s crooked cabinet. Over the years, their pieces have taken on more colour and experimental design, sometimes featuring pictures of masked group members, or splashy graphics designed to grab attention.

Their work is now held in collections around the world, including Tate and Getty, challenging the dynamics and statistics of the institutions themselves. They are also recognised for their powerful impact on street and protest art. Case in point, they have just opened a show at Beyond the Streets in Los Angeles, Laugh, Cry, Fight! … With the Guerrilla Girls, which looks back on their illustrious career.

Here, in their own words, the Guerrilla Girls’ two founding members – known as Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz – recount the energetic activism of their early years and share their hopes (and fears) for the future of US art and culture.

Frida Kahlo: When we started trying to make our way in the art world, we felt like it was a level playing field. Those of us who went to art school really felt we had the same opportunities as our fellow students. But when we started to look around it became clear that most opportunities were going to white men. At first we took it personally, like there was something wrong with us, and then when we talked to one another we realised there was something wrong with the system. I always felt like an outsider because I come from a completely different background from most of the people I encountered in the art world, so it seemed natural for me to start taking pokes at the establishment.

Käthe Kollwitz: We went to the demonstration at MoMA in 1985. A lot of women artists from every kind of art and background were really pissed off. The issue was, what do you do about it? The picket line did nothing. But that was the aha moment. There had to be a better way, a really in-your-face way of talking about, looking at, and thinking about this to change peoples’ minds. They thought that whatever was in the museum was the best. But if you weed out most of the artist population, how can that be?

FK: I felt particularly encouraged by other female artists but also by the feminist discourse that was coming up at the time. It gave me energy and courage. We started talking around; there were between seven and ten of us who got together from many different backgrounds and different ages. There were veterans of the early feminist movement and younger people. It was a very heady and wonderful time as we realised something had to be done. We knew that the art world was unfair in many ways, not just in terms of gender but in terms of ethnic background, age and social class. We had a lot of learning to do in terms of listening to other people and understanding it was all part of the same institutional problem.

KK: There were protests, people were talking about the incredible discrimination of women and people of colour, but nobody listened. The question was, how are we going to get the message out when nobody wants to hear it? The answer was: the street. It’s a place where people can look or not look, and we tried to make them different to the usual political posters.

“It’s not the history of culture but the history of wealth and power” – Guerrilla Girls

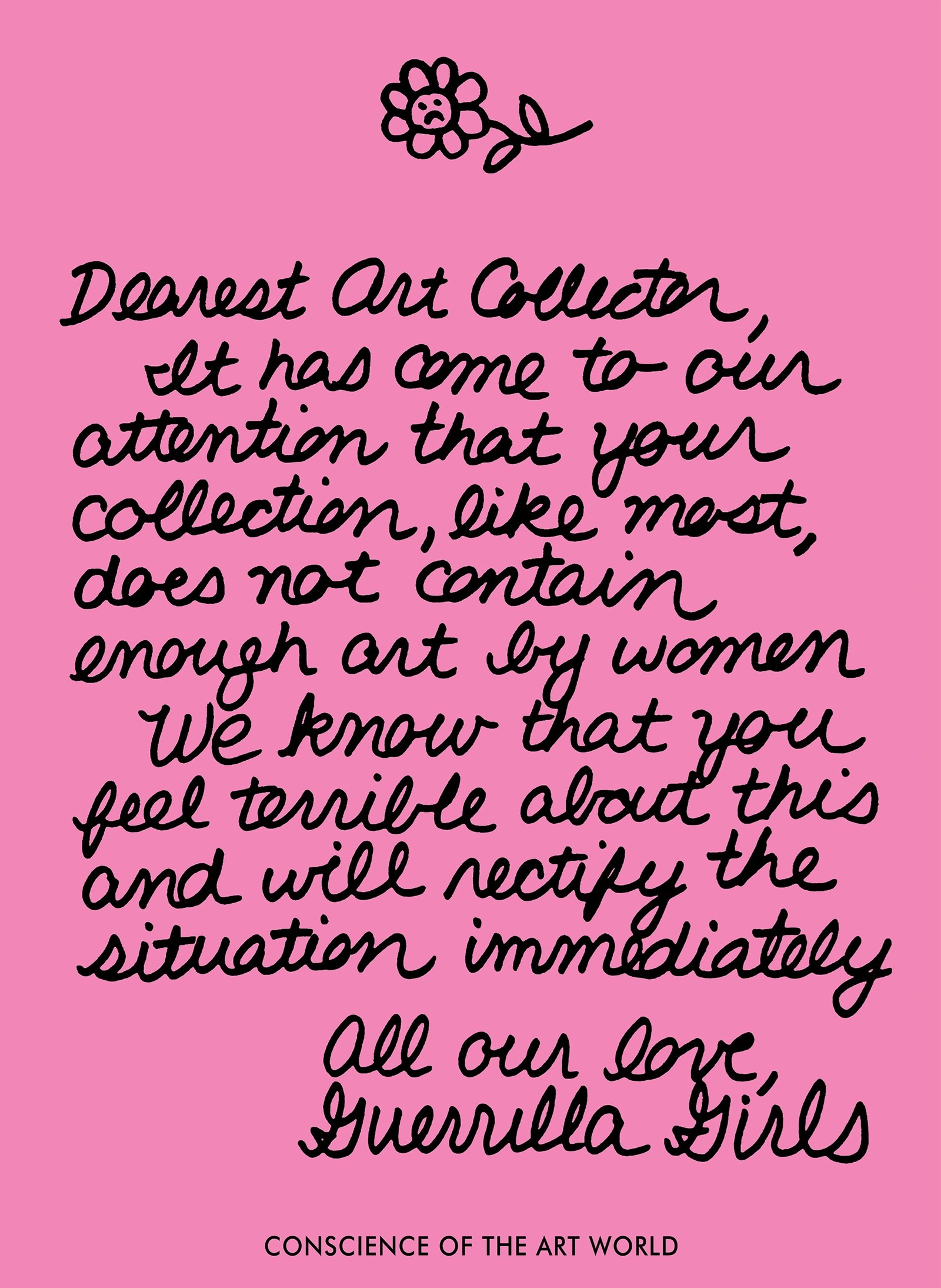

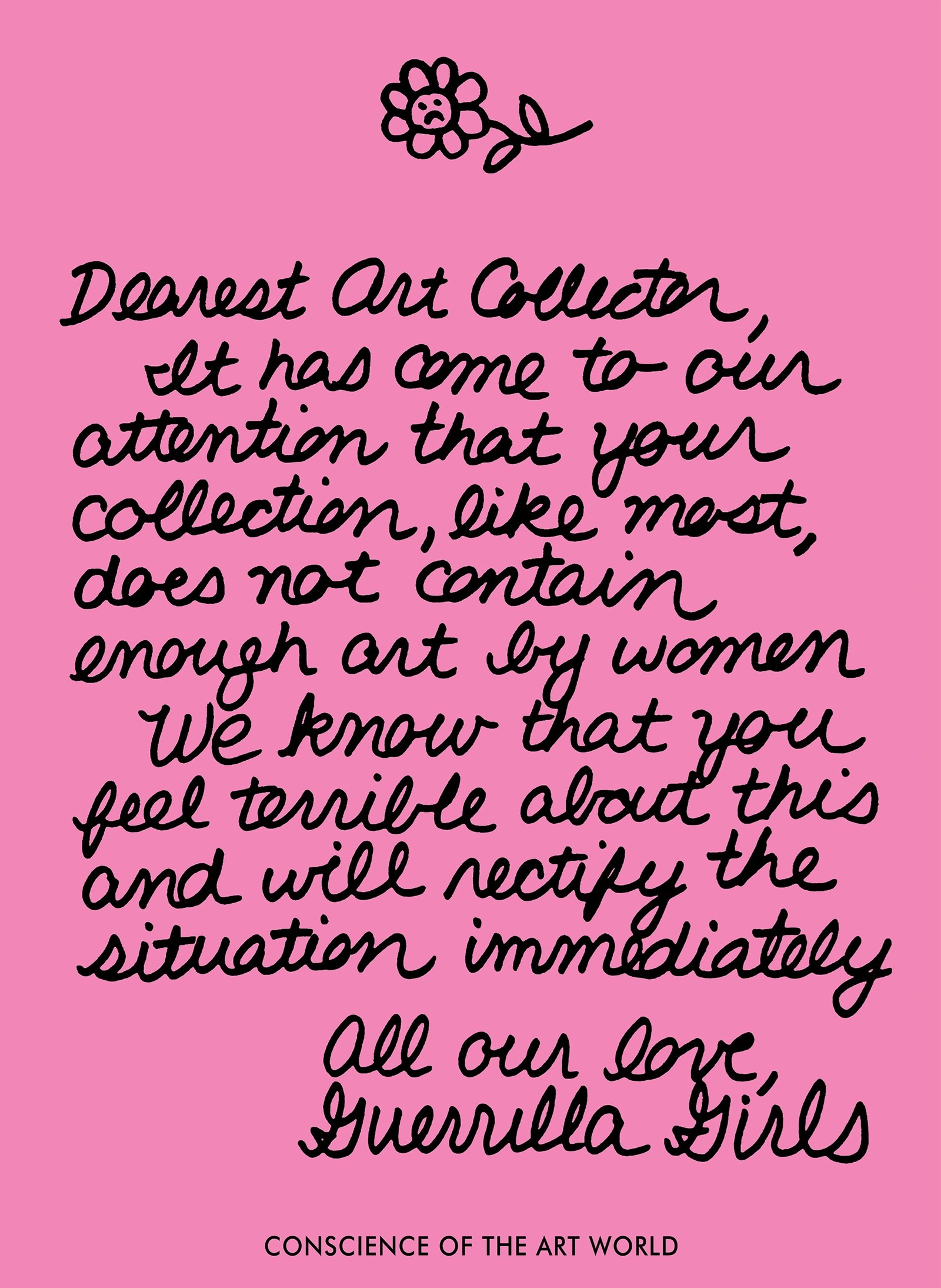

FK: We put every subgroup of the art world on the block to see what they had to say because everyone said that it was someone else’s fault. Why did our fellow artists allow their work to be shown at galleries that didn’t show women? What were the most egregious galleries? How many women were put in exhibitions? And then when we got to the collectors, we realised we had to suck up to them a little! We wrote them a pretty pink letter.

KK: It was a time when it was really difficult to get things printed. Almost 40 years ago, you had to have special skills to be able to give something to the printer and we couldn’t afford to do colour. It’s why the first posters were very simple; in your face. There wasn’t much argument about that. But later, as we did more things in different ways, there was a lot of back and forth. Some people in our group didn’t like humour. That was hard because in general, everybody was on board with that.

FK: Some people loved us, some hated us, but they couldn’t stop talking about us. We’d put the posters up on a Friday night around the galleries and go out on a Saturday afternoon and hear people talking about them. People were arguing and we could see they were thinking about something they hadn’t before, with new information. We always came away from those eavesdropping sessions with new ideas.

We were encouraged by the success we had in the art world and we wanted to change things on a larger scale. The abortion poster in 1992 was the year of one of the big pro-choice marches on Washington. You have to do a double take and read the small print [the poster’s top line reads “Guerrilla Girls Demand a Return to Traditional Values on Abortion”]. We made the scandalous statement and everyone went “What! You’re abandoning the March for choice?” And then we’d point to the small print [which begins, “Before the mid-19th century, abortion in the first few months of pregnancy was legal …”]. We were trying to say that abortion was a traditional value.

KK: People asked us to do new things, we were always trying stuff out. But the ideals stayed the same. Tell people something they didn’t know before in a way they can’t forget. At a certain point, the museums of the world came calling which was really interesting. Criticising a museum on its own walls was an amazing way for us to reach even more people.

FK: I think the consciousness of the art world has changed now, but systemically, it’s based on money. It used to be in Europe that the kings and queens and tsars told the rest of us what our high culture was. We live in a more democratic age now, so we should expect that taste isn’t informed by the rich and powerful, but the way the art market is organised. There’s a handful of billionaires who create the market and artists unfortunately feed them. It’s like feeding the beast. It’s a lousy way to write art history, it’s not the history of culture but the history of wealth and power. When we started that wasn’t necessarily the case.

KK: We are now in a really difficult time in the United States. Like many people, we are going to be speaking up and doing whatever we can.

“Tell people something they didn’t know before in a way they can’t forget” – Guerrilla Girls

FK: I think the challenge will be to continue doing critical thinking about the world of culture. The powers that be can’t keep us from thinking, researching, investigating, and continuing to write the incredible, interesting, rich, ever-evolving history of our culture as expressed through the arts. We can’t predict what’s going to happen and we can’t predict what people protesting it are going to do. Anyone who’s been involved in civil rights movements knows it’s two steps forward, one step back. We have to keep the trajectory heading towards progress, but it isn’t always a smooth ride. One thing we can do individually is make sure the people in our lives don’t behave badly. And call them out when they do.

KK: We value the art of complaining. We can’t make everything change, but so many people are at least trying. Art museums and the fancy art world aren’t the only things. Most of the creative work now is online, it’s a whole different world. You don’t have to wait for the powers that be to select you.

FK: The art world is looked upon by the political environment right now as a bunch of elitists. As a response, arts institutions can become a fortress to preserve cultural values until things get better.

Laugh, Cry, Fight! … With The Guerrilla Girls is on show at Beyond the Streets in Los Angeles until 18 January 2025.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageDo Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?, 1989Courtesy of Guerrilla Girls

As a group, the Guerrilla Girls have reached iconic status, yet their individual identities remain hidden behind identical gorilla masks (they are each anonymous and styled after high-profile women from previous generations). They got together in 1985, following a protest by women artists at MoMA which highlighted the lack of diversity in the museum’s survey show An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture.

Their street posters from the early years remain instantly recognisable: black text on white backgrounds highlighting the cold stats of collections and museums that almost always sway in favour of white men. Aimed at shaking up the art establishment, these pieces called on fellow artists, curators, collectors and gallerists to take action. Since then, they’ve used their bold visuals and no-nonsense approach to talk directly about abortion, imprisonment, and Trump’s crooked cabinet. Over the years, their pieces have taken on more colour and experimental design, sometimes featuring pictures of masked group members, or splashy graphics designed to grab attention.

Their work is now held in collections around the world, including Tate and Getty, challenging the dynamics and statistics of the institutions themselves. They are also recognised for their powerful impact on street and protest art. Case in point, they have just opened a show at Beyond the Streets in Los Angeles, Laugh, Cry, Fight! … With the Guerrilla Girls, which looks back on their illustrious career.

Here, in their own words, the Guerrilla Girls’ two founding members – known as Frida Kahlo and Käthe Kollwitz – recount the energetic activism of their early years and share their hopes (and fears) for the future of US art and culture.

Frida Kahlo: When we started trying to make our way in the art world, we felt like it was a level playing field. Those of us who went to art school really felt we had the same opportunities as our fellow students. But when we started to look around it became clear that most opportunities were going to white men. At first we took it personally, like there was something wrong with us, and then when we talked to one another we realised there was something wrong with the system. I always felt like an outsider because I come from a completely different background from most of the people I encountered in the art world, so it seemed natural for me to start taking pokes at the establishment.

Käthe Kollwitz: We went to the demonstration at MoMA in 1985. A lot of women artists from every kind of art and background were really pissed off. The issue was, what do you do about it? The picket line did nothing. But that was the aha moment. There had to be a better way, a really in-your-face way of talking about, looking at, and thinking about this to change peoples’ minds. They thought that whatever was in the museum was the best. But if you weed out most of the artist population, how can that be?

FK: I felt particularly encouraged by other female artists but also by the feminist discourse that was coming up at the time. It gave me energy and courage. We started talking around; there were between seven and ten of us who got together from many different backgrounds and different ages. There were veterans of the early feminist movement and younger people. It was a very heady and wonderful time as we realised something had to be done. We knew that the art world was unfair in many ways, not just in terms of gender but in terms of ethnic background, age and social class. We had a lot of learning to do in terms of listening to other people and understanding it was all part of the same institutional problem.

KK: There were protests, people were talking about the incredible discrimination of women and people of colour, but nobody listened. The question was, how are we going to get the message out when nobody wants to hear it? The answer was: the street. It’s a place where people can look or not look, and we tried to make them different to the usual political posters.

“It’s not the history of culture but the history of wealth and power” – Guerrilla Girls

FK: We put every subgroup of the art world on the block to see what they had to say because everyone said that it was someone else’s fault. Why did our fellow artists allow their work to be shown at galleries that didn’t show women? What were the most egregious galleries? How many women were put in exhibitions? And then when we got to the collectors, we realised we had to suck up to them a little! We wrote them a pretty pink letter.

KK: It was a time when it was really difficult to get things printed. Almost 40 years ago, you had to have special skills to be able to give something to the printer and we couldn’t afford to do colour. It’s why the first posters were very simple; in your face. There wasn’t much argument about that. But later, as we did more things in different ways, there was a lot of back and forth. Some people in our group didn’t like humour. That was hard because in general, everybody was on board with that.

FK: Some people loved us, some hated us, but they couldn’t stop talking about us. We’d put the posters up on a Friday night around the galleries and go out on a Saturday afternoon and hear people talking about them. People were arguing and we could see they were thinking about something they hadn’t before, with new information. We always came away from those eavesdropping sessions with new ideas.

We were encouraged by the success we had in the art world and we wanted to change things on a larger scale. The abortion poster in 1992 was the year of one of the big pro-choice marches on Washington. You have to do a double take and read the small print [the poster’s top line reads “Guerrilla Girls Demand a Return to Traditional Values on Abortion”]. We made the scandalous statement and everyone went “What! You’re abandoning the March for choice?” And then we’d point to the small print [which begins, “Before the mid-19th century, abortion in the first few months of pregnancy was legal …”]. We were trying to say that abortion was a traditional value.

KK: People asked us to do new things, we were always trying stuff out. But the ideals stayed the same. Tell people something they didn’t know before in a way they can’t forget. At a certain point, the museums of the world came calling which was really interesting. Criticising a museum on its own walls was an amazing way for us to reach even more people.

FK: I think the consciousness of the art world has changed now, but systemically, it’s based on money. It used to be in Europe that the kings and queens and tsars told the rest of us what our high culture was. We live in a more democratic age now, so we should expect that taste isn’t informed by the rich and powerful, but the way the art market is organised. There’s a handful of billionaires who create the market and artists unfortunately feed them. It’s like feeding the beast. It’s a lousy way to write art history, it’s not the history of culture but the history of wealth and power. When we started that wasn’t necessarily the case.

KK: We are now in a really difficult time in the United States. Like many people, we are going to be speaking up and doing whatever we can.

“Tell people something they didn’t know before in a way they can’t forget” – Guerrilla Girls

FK: I think the challenge will be to continue doing critical thinking about the world of culture. The powers that be can’t keep us from thinking, researching, investigating, and continuing to write the incredible, interesting, rich, ever-evolving history of our culture as expressed through the arts. We can’t predict what’s going to happen and we can’t predict what people protesting it are going to do. Anyone who’s been involved in civil rights movements knows it’s two steps forward, one step back. We have to keep the trajectory heading towards progress, but it isn’t always a smooth ride. One thing we can do individually is make sure the people in our lives don’t behave badly. And call them out when they do.

KK: We value the art of complaining. We can’t make everything change, but so many people are at least trying. Art museums and the fancy art world aren’t the only things. Most of the creative work now is online, it’s a whole different world. You don’t have to wait for the powers that be to select you.

FK: The art world is looked upon by the political environment right now as a bunch of elitists. As a response, arts institutions can become a fortress to preserve cultural values until things get better.

Laugh, Cry, Fight! … With The Guerrilla Girls is on show at Beyond the Streets in Los Angeles until 18 January 2025.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.