Rewrite

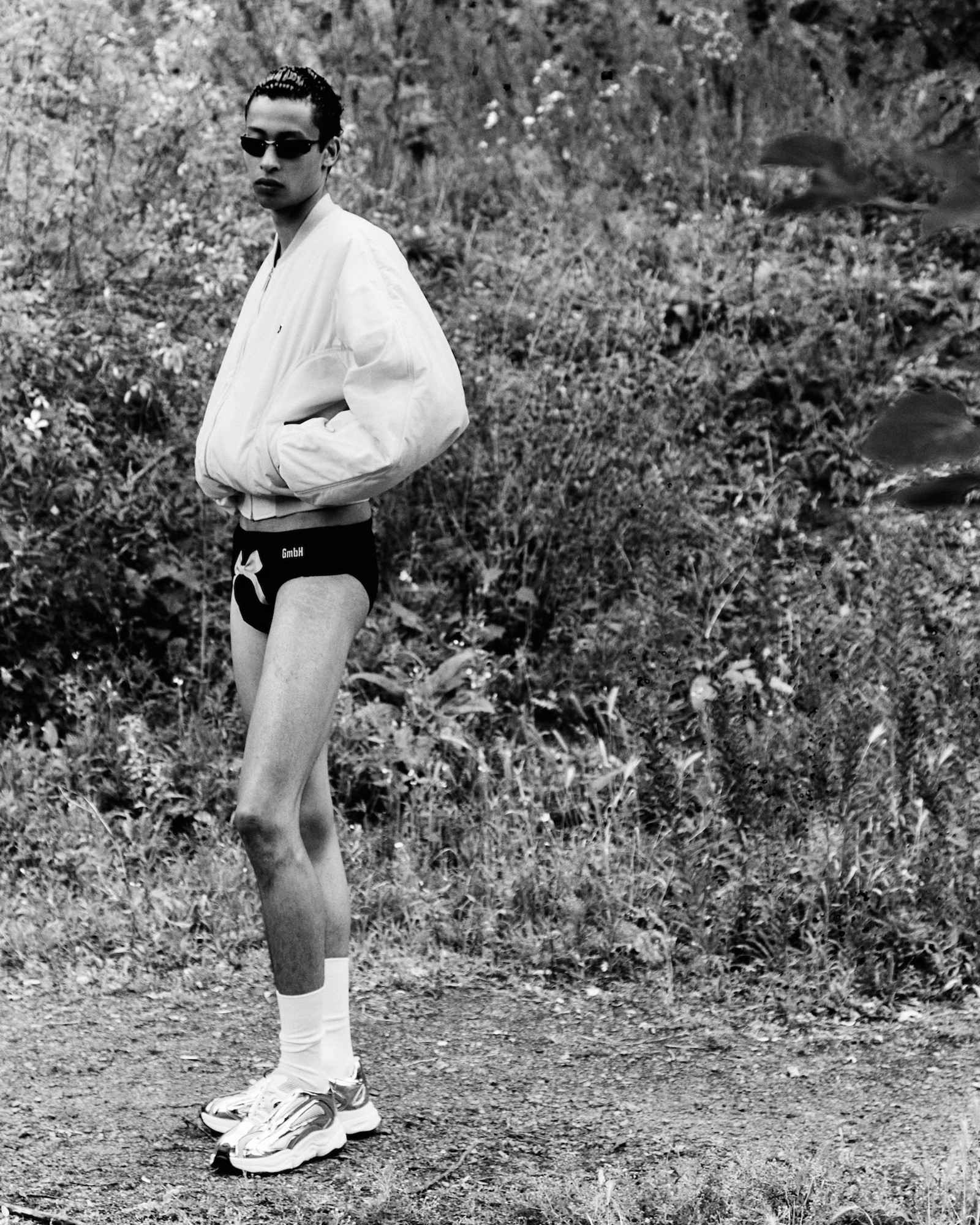

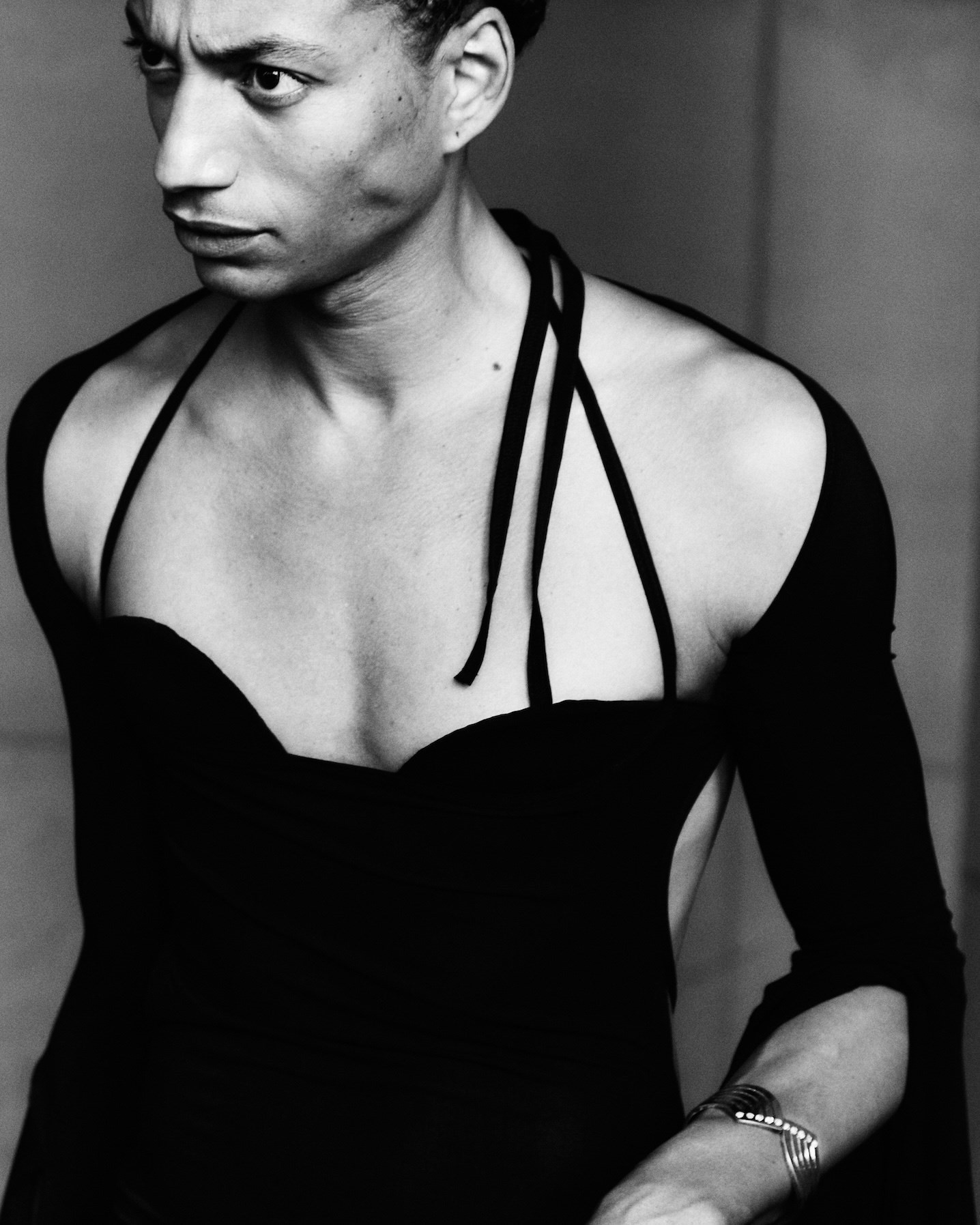

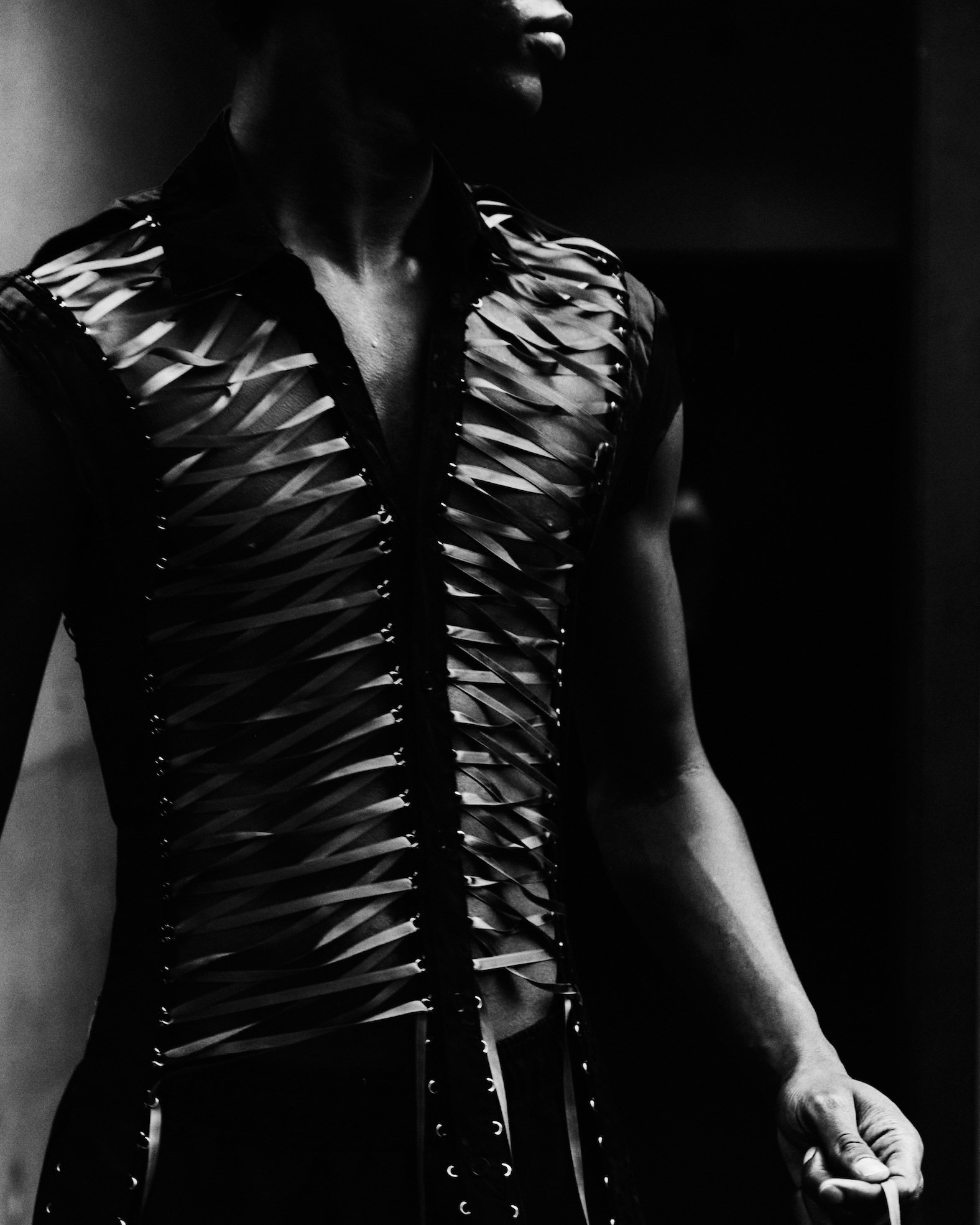

Lead ImageGmbH Spring/Summer 2025Photography by Harry Miller

The heavens opened a few minutes before GmbH were set to present their Spring/Summer 2025 collection on the open roof of Berlin’s Tempodrom, as eager teams of ultra-fashionable art school kids smoked under slivers of shelter and PRs whipped out paper towels to mop the soggy benches. The label’s founders Benjamin Alexander Huseby and Serhat Işık had explained over Zoom the week prior that the show would pay tribute to their friends and allies in intersectional communities fighting for a better world in a steadily far-right-leaning climate. So, as the models emerged onto the runway, there was beautiful apropos in that drizzle.

As a catch-all descriptor, ‘radical’ is used a lot when considering the work of many designers, but there’s real justification when it comes to Huseby and Işık. Where other brands accept political complexities and address them sweepingly in show notes, or allow them to inform a general ‘mood’, Huseby and Işık elucidate a sense of humanity so fluently they’ve been known to bring their spectators to tears. GmbH has always had multiculturalism at its heart – Huseby is of Pakistani-Norwegian descent, Işık is Turkish-German – and their designs speak to a vast community beyond Berlin and the sweaty dancefloors where the brand was born. “This collection is a celebration of resistance in many ways, from within our community, whether queer, brown, or a part of an intersectional community,” Huseby explains.

Here, resistance manifested in a readiness to fight. Through the wet, out came blazers with lapels that turn into hoods, akin to the gowns boxers wear in the ring, while skimpy shorts were fitted with a thick, elasticated Muay Thai waistband. “Physical and protective clothing has always been a part of our work, but it’s also the spiritual and emotional side of fighting back,” says Işık. “I guess you can think of our lineup as a fight club for ‘love and justice’.” That mantra came printed on skin-tight vests and utilitarian bomber jackets, referencing the Japanese manga series Sailor Moon, while asymmetrical dresses were given a superhero feel with handkerchief sleeves that plume from the wrist. Styled for the first time by Another Man editor-in-chief Ellie Grace Cumming, the big takeaway was a sense of louche self-preservation – a modern armour for the socially powerful but politically vulnerable, pumped through the carnal frisson of the throbbing Berlin party scene. “Now, more than ever, it’s important to show our culture and community in Berlin, our hometown,” says Huseby.

Despite the liberal, bohemian myths that surrounds Berlin, the last nine months have been a challenging period for their immigrant artists. In an intense bout of censorship, German authorities have recently cancelled hundreds of events, including talks, film screenings and exhibitions, either due to them directly addressing Palestinian issues or because the artists involved had previously expressed pro-Palestinian views. A wave of police brutality has also ripped through Arab communities in response to protests against the genocide in the Gaza Strip. More generally across the country, this has been accompanied by a soaring cost of living, the cutting back of arts funding, and a notable rise in young people voting for the far-right parties in the European elections. “It’s a strange environment now. As of yesterday, if you like a post that [the authorities] thinks is ‘incorrect’ you can actually be deported,” says Huseby, who is choosing his words carefully to avoid the same fate. “Broad strokes of politicians and press have really tried to criminalise so many people over the last seven or eight months: artists, Jews, Palestinians, Arabs – anyone that speaks up against war crimes, or with any kind of criticism.”

“Now, more than ever, it’s important to show our culture and community in Berlin, our hometown” – Benjamin Alexander Huseby

In January of this year, at the GmbH show in Paris, the designers took to a podium wearing keffiyehs to give a powerful ten-minute speech about the ongoing genocide in Gaza, where the death toll had reached around 25,000. Now, at the time of publishing, this number has spiralled to almost 38,000, with a further two million displaced. The speech paged for an immediate ceasefire, a release of all hostages, called out the parallel rise of antisemitism, and concluded with a lengthy excerpt from Arundhati Roy’s powerful speech Come September. “It felt like a collective sigh of relief,” Işık says of the public reception to the speech. “We said something within the industry that a lot of people were thinking for a long time, but maybe weren’t ready or able to speak about it.” Fashion doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and this vision of empathy is, frustratingly, a rarity. “It felt cathartic,” Huseby adds. “I don’t know anyone else who has opened a scheduled fashion show with a ten-minute speech. It seems incredibly self-indulgent, but it felt important.”

Since that moment, the net was cast for a wider community united in their objective for peace. At the Tempodrom, many members of the community sat in the front row, while others, like dancer and choreographer MJ Harper, flew to Berlin to walk. “What’s come out of this, and what gives me hope, is the stronger bonds between certain communities, and what I will call a sense of resistance across different cultural fields,” says Huseby. “There is hope, even though it seems dark at times.”

The duo know what it is like to live in a world where the cards are stacked against you, and they understand that there is a power in clothing that can be easily forgotten when politics become fraught. Even without a ten-minute speech, the GmbH voices of dissent remain crystal clear. Perhaps their actions do speak as loud as their words. “A lot of the topics we talk about are very heavy,” says Huseby, “but it’s important to see this show as a celebration.”

Just as the models made their final heroic procession, the clouds seemed to shift, umbrellas were collapsed, and a warm sunlight made its way from above. Better late than never. Backstage after the show, surrounded by their friends and community who each hugged and kissed them, Huseby and Işık were touched to hear there had been a happy ending. It felt like part of a larger message about the triumph of good over evil, where their gesture towards a radical version of beauty not only renewed some faith in their home of Berlin, but in fashion in general. This was a version of beauty that stood proudly with migrants, queers, Muslims and Jews. As a tribute to those who believe in a better world and are willing to fight for it, I can’t think of a better conclusion than that.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageGmbH Spring/Summer 2025Photography by Harry Miller

The heavens opened a few minutes before GmbH were set to present their Spring/Summer 2025 collection on the open roof of Berlin’s Tempodrom, as eager teams of ultra-fashionable art school kids smoked under slivers of shelter and PRs whipped out paper towels to mop the soggy benches. The label’s founders Benjamin Alexander Huseby and Serhat Işık had explained over Zoom the week prior that the show would pay tribute to their friends and allies in intersectional communities fighting for a better world in a steadily far-right-leaning climate. So, as the models emerged onto the runway, there was beautiful apropos in that drizzle.

As a catch-all descriptor, ‘radical’ is used a lot when considering the work of many designers, but there’s real justification when it comes to Huseby and Işık. Where other brands accept political complexities and address them sweepingly in show notes, or allow them to inform a general ‘mood’, Huseby and Işık elucidate a sense of humanity so fluently they’ve been known to bring their spectators to tears. GmbH has always had multiculturalism at its heart – Huseby is of Pakistani-Norwegian descent, Işık is Turkish-German – and their designs speak to a vast community beyond Berlin and the sweaty dancefloors where the brand was born. “This collection is a celebration of resistance in many ways, from within our community, whether queer, brown, or a part of an intersectional community,” Huseby explains.

Here, resistance manifested in a readiness to fight. Through the wet, out came blazers with lapels that turn into hoods, akin to the gowns boxers wear in the ring, while skimpy shorts were fitted with a thick, elasticated Muay Thai waistband. “Physical and protective clothing has always been a part of our work, but it’s also the spiritual and emotional side of fighting back,” says Işık. “I guess you can think of our lineup as a fight club for ‘love and justice’.” That mantra came printed on skin-tight vests and utilitarian bomber jackets, referencing the Japanese manga series Sailor Moon, while asymmetrical dresses were given a superhero feel with handkerchief sleeves that plume from the wrist. Styled for the first time by Another Man editor-in-chief Ellie Grace Cumming, the big takeaway was a sense of louche self-preservation – a modern armour for the socially powerful but politically vulnerable, pumped through the carnal frisson of the throbbing Berlin party scene. “Now, more than ever, it’s important to show our culture and community in Berlin, our hometown,” says Huseby.

Despite the liberal, bohemian myths that surrounds Berlin, the last nine months have been a challenging period for their immigrant artists. In an intense bout of censorship, German authorities have recently cancelled hundreds of events, including talks, film screenings and exhibitions, either due to them directly addressing Palestinian issues or because the artists involved had previously expressed pro-Palestinian views. A wave of police brutality has also ripped through Arab communities in response to protests against the genocide in the Gaza Strip. More generally across the country, this has been accompanied by a soaring cost of living, the cutting back of arts funding, and a notable rise in young people voting for the far-right parties in the European elections. “It’s a strange environment now. As of yesterday, if you like a post that [the authorities] thinks is ‘incorrect’ you can actually be deported,” says Huseby, who is choosing his words carefully to avoid the same fate. “Broad strokes of politicians and press have really tried to criminalise so many people over the last seven or eight months: artists, Jews, Palestinians, Arabs – anyone that speaks up against war crimes, or with any kind of criticism.”

“Now, more than ever, it’s important to show our culture and community in Berlin, our hometown” – Benjamin Alexander Huseby

In January of this year, at the GmbH show in Paris, the designers took to a podium wearing keffiyehs to give a powerful ten-minute speech about the ongoing genocide in Gaza, where the death toll had reached around 25,000. Now, at the time of publishing, this number has spiralled to almost 38,000, with a further two million displaced. The speech paged for an immediate ceasefire, a release of all hostages, called out the parallel rise of antisemitism, and concluded with a lengthy excerpt from Arundhati Roy’s powerful speech Come September. “It felt like a collective sigh of relief,” Işık says of the public reception to the speech. “We said something within the industry that a lot of people were thinking for a long time, but maybe weren’t ready or able to speak about it.” Fashion doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and this vision of empathy is, frustratingly, a rarity. “It felt cathartic,” Huseby adds. “I don’t know anyone else who has opened a scheduled fashion show with a ten-minute speech. It seems incredibly self-indulgent, but it felt important.”

Since that moment, the net was cast for a wider community united in their objective for peace. At the Tempodrom, many members of the community sat in the front row, while others, like dancer and choreographer MJ Harper, flew to Berlin to walk. “What’s come out of this, and what gives me hope, is the stronger bonds between certain communities, and what I will call a sense of resistance across different cultural fields,” says Huseby. “There is hope, even though it seems dark at times.”

The duo know what it is like to live in a world where the cards are stacked against you, and they understand that there is a power in clothing that can be easily forgotten when politics become fraught. Even without a ten-minute speech, the GmbH voices of dissent remain crystal clear. Perhaps their actions do speak as loud as their words. “A lot of the topics we talk about are very heavy,” says Huseby, “but it’s important to see this show as a celebration.”

Just as the models made their final heroic procession, the clouds seemed to shift, umbrellas were collapsed, and a warm sunlight made its way from above. Better late than never. Backstage after the show, surrounded by their friends and community who each hugged and kissed them, Huseby and Işık were touched to hear there had been a happy ending. It felt like part of a larger message about the triumph of good over evil, where their gesture towards a radical version of beauty not only renewed some faith in their home of Berlin, but in fashion in general. This was a version of beauty that stood proudly with migrants, queers, Muslims and Jews. As a tribute to those who believe in a better world and are willing to fight for it, I can’t think of a better conclusion than that.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.

この記事の最初の掲載場所: www.anothermag.com