Rewrite

As Peter Hujar’s Day is released, here are ten films and documentaries that show what the life of a photographer is really like behind the lens

They may not enjoy being on the other side of the lens, but photographers make for fascinating subjects. Thankfully for us, there’s no shortage of films, both fictional and factual, that turn the camera the other way and show us what it’s really like to be a photographer.

In just the past year, several documentaries were released that centred on specific photographers: the late Martin Parr in Lee Shulman’s I Am Martin Parr and Joel Meyerowitz (with his wife Maggie Barrett) in the brilliant Two Strangers Trying Not to Kill Each Other. Most recently, National Geographic released Love + War, a documentary about the Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Lynsey Addario. This last year has also seen fictional films released where the main character is a photographer, like Amazon Prime’s Picture This.

The reason for the abundance of titles is simple. Photographers, perhaps with the exception of the paparazzi, enjoy social currency in our culture. As audiences, we’re eager to understand what the life of a photographer is really like behind the mystique of artistry. We all secretly long to know what artists do all day.

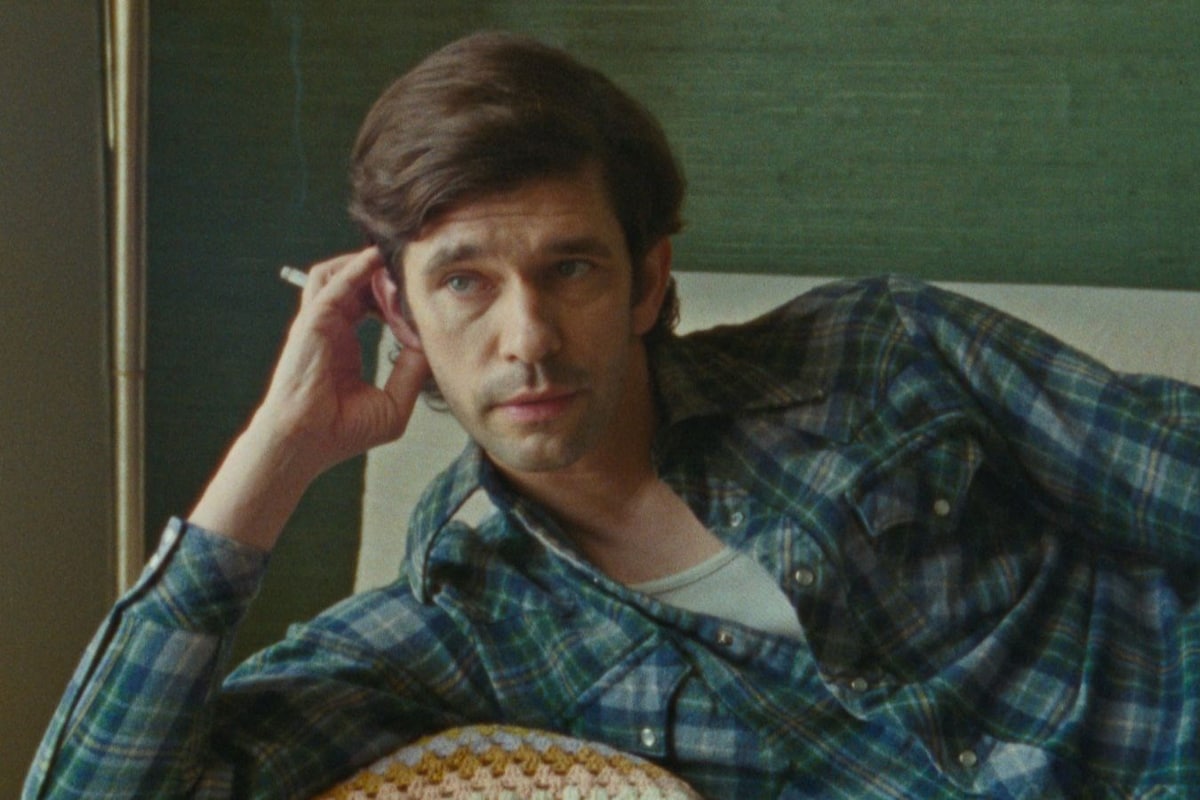

Ira Sachs’s new film Peter Hujar’s Day explores this idea quite literally. Based on Linda Rosenkrantz’s book, the film is simply a conversation between Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall) and the American photographer Peter Hujar (Ben Whishaw), in which Rosenkrantz asks Hujar to recount what he did the previous day. Luckily for viewers, Hujar had a busy day – a phone call from Susan Sontag, negotiations with editors, a photoshoot with Allen Ginsberg. Peter Hujar’s Day is not particularly eventful – it’s simply a conversation, albeit one that’s beautifully shot – but the film reveals the mundanities and contradictions inherent in professional photography: glamour and praise is mixed with creative jealousies and anxieties about money. As with most photographers, there’s always a more complex truth hidden beneath surface appearances.

As Peter Hujar’s Day is released in cinemas, here are ten more films about being a photographer.

Nan Goldin made a name for herself photographing the queer scene in 1980s New York. In recent years, she has become one of America’s most ardent campaigners as the country battles the opioid epidemic. Directed by legendary documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed is a biography of Goldin, both as photographer and as social activist. Slides from Goldin’s legendary series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency are mixed with footage of her direct actions targeting the Sackler family (for its role in fueling the opioid crisis) and the art galleries that accept Sackler money.

Read our interview with the director here.

When John Maloof bought a box of photo negatives at an auction, he had no idea he was about to stumble upon one of photography’s greatest mysteries. Vivian Maier, who died in 2009, left over 100,000 negatives. She is now regarded as one of the greatest street photographers of all time, but she was fiercely private, working as a nanny in New York and never showing her photographs to anyone. Finding Vivian Maier confronts a difficult question. Maier purposely did not share her work while she was alive, and so Maloof and others ponder the balance between respecting privacy and sharing the work of a great photographer with the world.

Read our feature on Vivian Maier here.

For Sally Mann, beauty is never just beautiful; there is always a current of disquiet beneath her large-format images. Mann came to public attention in the early 90s for her photographs of her children, often in the nude. Steven Cantor’s 2005 documentary follows Mann as she continues to photograph her family, her landscape and, in the film’s most memorable sequence, dead bodies left to decompose in the open air as part of a medical research project. What remains shows the precariousness of being an artist: we see Mann’s reaction to New York’s Pace Gallery deciding to cancel a planned show of her work four months before the scheduled opening.

Read our interview with Sally Mann here.

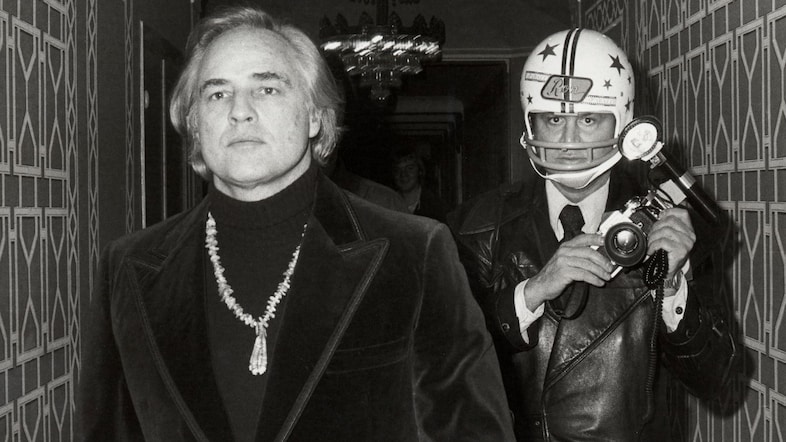

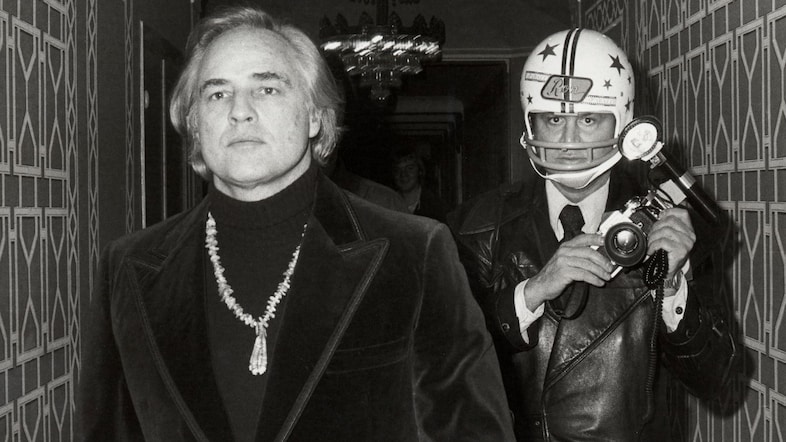

Ron Galella was the king of paparazzi photography. As the documentary Smash His Camera explores, Galella’s behaviour was close to stalking. He had no qualms about photographing celebrities whenever he could, and naturally, made quite a few enemies. (In 1973, Marlon Brando punched Galella outside of a Chinese restaurant, breaking his jaw. The next time Galella photographed the actor, he wore a football helmet.) Smash His Camera is good as a way of thinking about the ethics of photography – though one may be legally allowed to take a photograph in public, does that mean it’s right? Galella was fearless. It’s why he is considered the greatest paparazzo to have ever lived. And why so many people wanted to smash his camera.

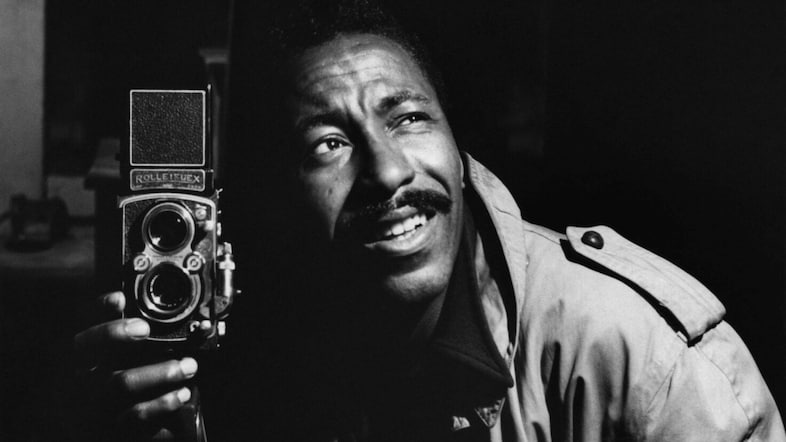

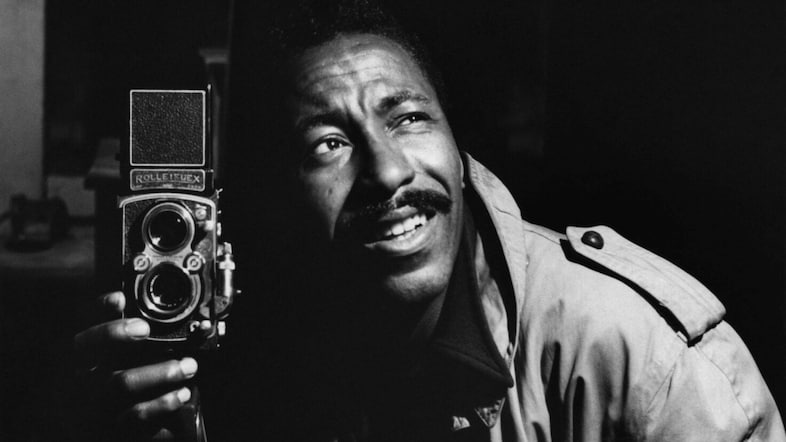

Gordon Parks was a man of many talents. He was a film director, a poet, a novelist, a musician, as well as an iconic photographer, capturing racial injustice in the United States. For Parks, the camera was a weapon; he might have turned to the gun or the knife, he once said, but instead he turned to the camera. What makes A Choice of Weapons special is its focus not just on Parks himself but on contemporary photographers who have been inspired by him. A Choice of Weapons is as much about today’s generation of photographers – shooting protests and social movements – as it is about Parks, which is a pretty decent way to honour his legacy.

Read our feature on Gordon Parks here.

Matt Smith gave a memorable performance as Robert Mapplethorpe in Ondi Timoner’s 2018 biopic of the provocative photographer. Mapplethorpe made his name with his bold, sexually charged images of the BDSM scene, leather and penises. Even his flowers are erotic and phallic. Mapplethorpe charts the photographer’s ascension to fame, his drug troubles and his eventual death from HIV/AIDS. But the film raises important questions about professional photography – namely, the importance of artistic vision versus technical perfection, and the hypocrisy of an art market that hates you one minute and loves you the next, when they realise they can make money from your name.

Read more about Robert Mapplethorpe here.

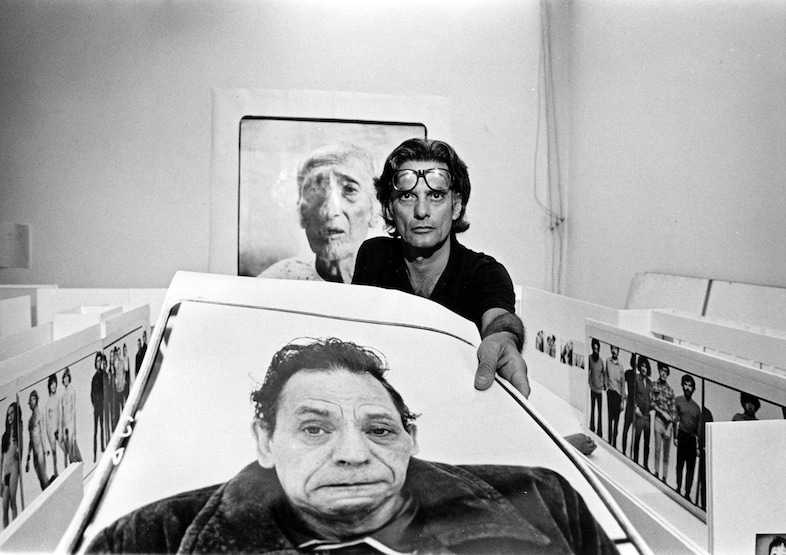

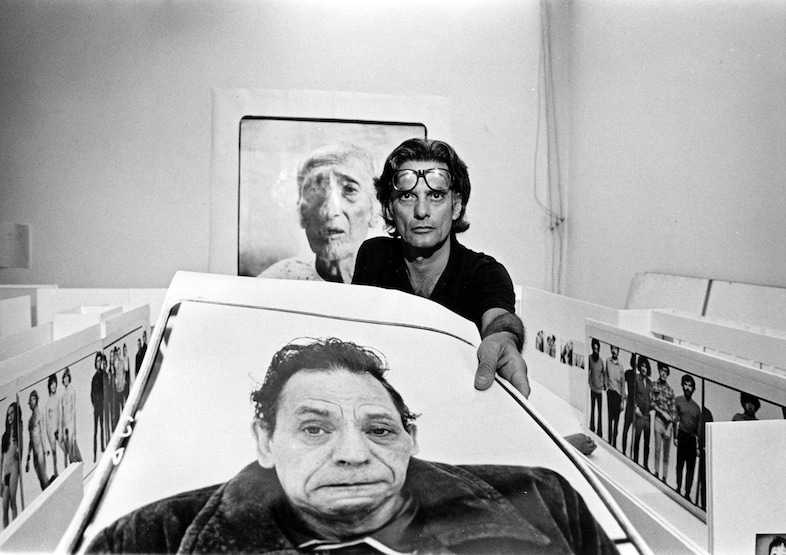

Richard Avedon’s style was simple: black-and-white portraits in front of a white background. But with his stripped back approach, Avedon created some of the most iconic portraits of the 20th century. His subjects ranged from Robert Oppenheimer to Marilyn Monroe to ordinary farmers in Texas. Made when he was still alive, Darkness and Light sees Avedon talk about his work and approach to photography. The film is littered with anecdotes from one of fashion’s greatest photographers, but also insights into why Avedon chose this profession. The camera helped Avedon confront things he didn’t understand, like women and death.

As the title suggests, Fur is not an accurate biography of Diane Arbus. In real life, the photographer was drawn to people on the margins in mid-century America: cross-dressers, nudists, carnival performers, people with disabilities. In Fur, Arbus (played by Nicole Kidman) falls in love with Lionel Sweeney, a man afflicted by abnormal hair growth, played by Robert Downey Jr. The film received mixed reviews, with many taking issue with the film’s lax approach to fact and fiction. But despite what some people think, photography has never been synonymous with objective truth. Moreover, Arbus was one of photography’s most ethically divisive figures. (Susan Sontag criticised her work as being exploitative and without compassion.) A film that takes liberties with the truth therefore is a pretty appropriate tribute to Arbus.

Read our feature on Diane Arbus here.

If any photographer is deserving of a biopic, it’s Lee Miller. She was a model in Paris, a collaborator and muse of Man Ray, and a frequent photographer for Vogue. But Lee, starring and produced by Kate Winslet, skips over much of this glamour, focusing instead on Miller’s war photography. Angry at the access granted to her male peers, Miller found a way to shoot the battlefields of World War II and was among the first photographers to shoot the horrors of the Holocaust shortly after liberation. The experiences of war had a profound effect on her, which Lee acutely captures.

Read our feature on Lee Miller here.

There have been a few documentaries made about Helmut Newton – Frames from the Edge (1989) and The Bad and the Beautiful (2020) – but none are as illuminating as the one made by his wife, Helmut by June. Shot on a home video camera, the film is an intriguing cinéma vérité look at a man whose photography is synonymous with sex, nudity and provocation from the loving eye of a spouse. Helmut by June is more intimate than just a fly-on-the-wall observation; we hear June’s narration as we watch her husband photograph nude models – “He loves big women … because he can manipulate them” – and get a glimpse of being married to photography’s famous enfant terrible.

Peter Hujar’s Day is out in UK cinemas now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

As Peter Hujar’s Day is released, here are ten films and documentaries that show what the life of a photographer is really like behind the lens

They may not enjoy being on the other side of the lens, but photographers make for fascinating subjects. Thankfully for us, there’s no shortage of films, both fictional and factual, that turn the camera the other way and show us what it’s really like to be a photographer.

In just the past year, several documentaries were released that centred on specific photographers: the late Martin Parr in Lee Shulman’s I Am Martin Parr and Joel Meyerowitz (with his wife Maggie Barrett) in the brilliant Two Strangers Trying Not to Kill Each Other. Most recently, National Geographic released Love + War, a documentary about the Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Lynsey Addario. This last year has also seen fictional films released where the main character is a photographer, like Amazon Prime’s Picture This.

The reason for the abundance of titles is simple. Photographers, perhaps with the exception of the paparazzi, enjoy social currency in our culture. As audiences, we’re eager to understand what the life of a photographer is really like behind the mystique of artistry. We all secretly long to know what artists do all day.

Ira Sachs’s new film Peter Hujar’s Day explores this idea quite literally. Based on Linda Rosenkrantz’s book, the film is simply a conversation between Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall) and the American photographer Peter Hujar (Ben Whishaw), in which Rosenkrantz asks Hujar to recount what he did the previous day. Luckily for viewers, Hujar had a busy day – a phone call from Susan Sontag, negotiations with editors, a photoshoot with Allen Ginsberg. Peter Hujar’s Day is not particularly eventful – it’s simply a conversation, albeit one that’s beautifully shot – but the film reveals the mundanities and contradictions inherent in professional photography: glamour and praise is mixed with creative jealousies and anxieties about money. As with most photographers, there’s always a more complex truth hidden beneath surface appearances.

As Peter Hujar’s Day is released in cinemas, here are ten more films about being a photographer.

Nan Goldin made a name for herself photographing the queer scene in 1980s New York. In recent years, she has become one of America’s most ardent campaigners as the country battles the opioid epidemic. Directed by legendary documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed is a biography of Goldin, both as photographer and as social activist. Slides from Goldin’s legendary series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency are mixed with footage of her direct actions targeting the Sackler family (for its role in fueling the opioid crisis) and the art galleries that accept Sackler money.

Read our interview with the director here.

When John Maloof bought a box of photo negatives at an auction, he had no idea he was about to stumble upon one of photography’s greatest mysteries. Vivian Maier, who died in 2009, left over 100,000 negatives. She is now regarded as one of the greatest street photographers of all time, but she was fiercely private, working as a nanny in New York and never showing her photographs to anyone. Finding Vivian Maier confronts a difficult question. Maier purposely did not share her work while she was alive, and so Maloof and others ponder the balance between respecting privacy and sharing the work of a great photographer with the world.

Read our feature on Vivian Maier here.

For Sally Mann, beauty is never just beautiful; there is always a current of disquiet beneath her large-format images. Mann came to public attention in the early 90s for her photographs of her children, often in the nude. Steven Cantor’s 2005 documentary follows Mann as she continues to photograph her family, her landscape and, in the film’s most memorable sequence, dead bodies left to decompose in the open air as part of a medical research project. What remains shows the precariousness of being an artist: we see Mann’s reaction to New York’s Pace Gallery deciding to cancel a planned show of her work four months before the scheduled opening.

Read our interview with Sally Mann here.

Ron Galella was the king of paparazzi photography. As the documentary Smash His Camera explores, Galella’s behaviour was close to stalking. He had no qualms about photographing celebrities whenever he could, and naturally, made quite a few enemies. (In 1973, Marlon Brando punched Galella outside of a Chinese restaurant, breaking his jaw. The next time Galella photographed the actor, he wore a football helmet.) Smash His Camera is good as a way of thinking about the ethics of photography – though one may be legally allowed to take a photograph in public, does that mean it’s right? Galella was fearless. It’s why he is considered the greatest paparazzo to have ever lived. And why so many people wanted to smash his camera.

Gordon Parks was a man of many talents. He was a film director, a poet, a novelist, a musician, as well as an iconic photographer, capturing racial injustice in the United States. For Parks, the camera was a weapon; he might have turned to the gun or the knife, he once said, but instead he turned to the camera. What makes A Choice of Weapons special is its focus not just on Parks himself but on contemporary photographers who have been inspired by him. A Choice of Weapons is as much about today’s generation of photographers – shooting protests and social movements – as it is about Parks, which is a pretty decent way to honour his legacy.

Read our feature on Gordon Parks here.

Matt Smith gave a memorable performance as Robert Mapplethorpe in Ondi Timoner’s 2018 biopic of the provocative photographer. Mapplethorpe made his name with his bold, sexually charged images of the BDSM scene, leather and penises. Even his flowers are erotic and phallic. Mapplethorpe charts the photographer’s ascension to fame, his drug troubles and his eventual death from HIV/AIDS. But the film raises important questions about professional photography – namely, the importance of artistic vision versus technical perfection, and the hypocrisy of an art market that hates you one minute and loves you the next, when they realise they can make money from your name.

Read more about Robert Mapplethorpe here.

Richard Avedon’s style was simple: black-and-white portraits in front of a white background. But with his stripped back approach, Avedon created some of the most iconic portraits of the 20th century. His subjects ranged from Robert Oppenheimer to Marilyn Monroe to ordinary farmers in Texas. Made when he was still alive, Darkness and Light sees Avedon talk about his work and approach to photography. The film is littered with anecdotes from one of fashion’s greatest photographers, but also insights into why Avedon chose this profession. The camera helped Avedon confront things he didn’t understand, like women and death.

As the title suggests, Fur is not an accurate biography of Diane Arbus. In real life, the photographer was drawn to people on the margins in mid-century America: cross-dressers, nudists, carnival performers, people with disabilities. In Fur, Arbus (played by Nicole Kidman) falls in love with Lionel Sweeney, a man afflicted by abnormal hair growth, played by Robert Downey Jr. The film received mixed reviews, with many taking issue with the film’s lax approach to fact and fiction. But despite what some people think, photography has never been synonymous with objective truth. Moreover, Arbus was one of photography’s most ethically divisive figures. (Susan Sontag criticised her work as being exploitative and without compassion.) A film that takes liberties with the truth therefore is a pretty appropriate tribute to Arbus.

Read our feature on Diane Arbus here.

If any photographer is deserving of a biopic, it’s Lee Miller. She was a model in Paris, a collaborator and muse of Man Ray, and a frequent photographer for Vogue. But Lee, starring and produced by Kate Winslet, skips over much of this glamour, focusing instead on Miller’s war photography. Angry at the access granted to her male peers, Miller found a way to shoot the battlefields of World War II and was among the first photographers to shoot the horrors of the Holocaust shortly after liberation. The experiences of war had a profound effect on her, which Lee acutely captures.

Read our feature on Lee Miller here.

There have been a few documentaries made about Helmut Newton – Frames from the Edge (1989) and The Bad and the Beautiful (2020) – but none are as illuminating as the one made by his wife, Helmut by June. Shot on a home video camera, the film is an intriguing cinéma vérité look at a man whose photography is synonymous with sex, nudity and provocation from the loving eye of a spouse. Helmut by June is more intimate than just a fly-on-the-wall observation; we hear June’s narration as we watch her husband photograph nude models – “He loves big women … because he can manipulate them” – and get a glimpse of being married to photography’s famous enfant terrible.

Peter Hujar’s Day is out in UK cinemas now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.