Rewrite

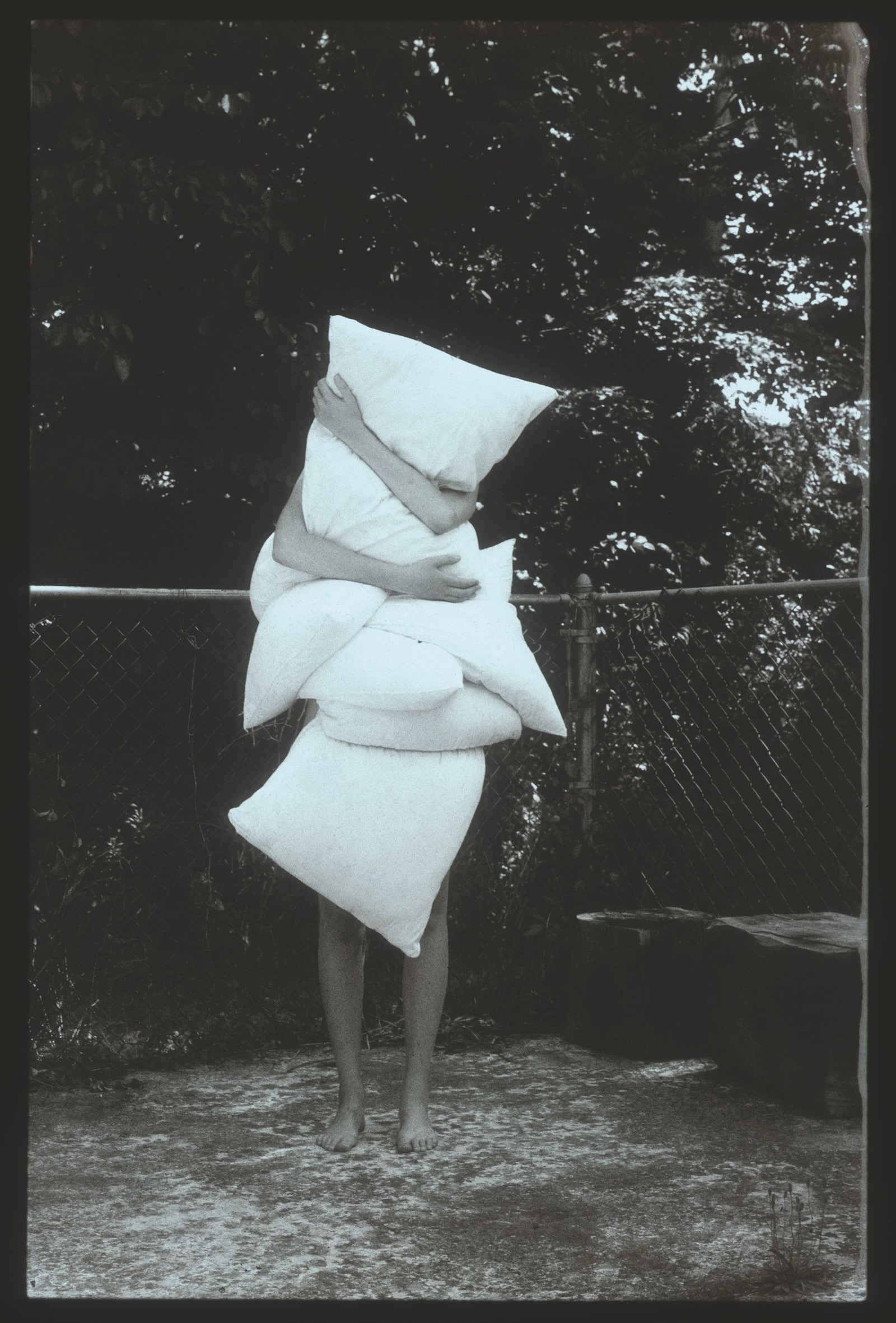

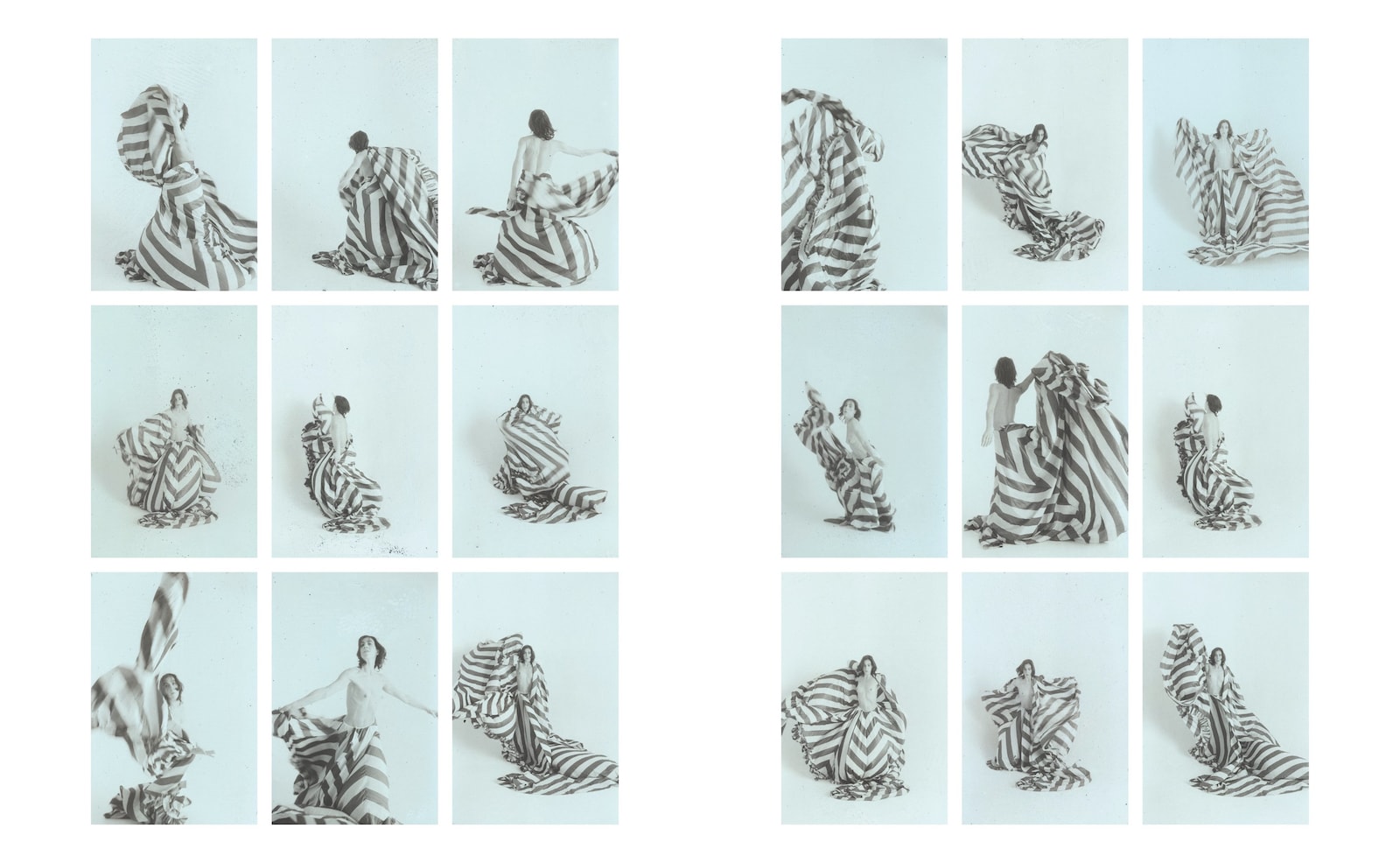

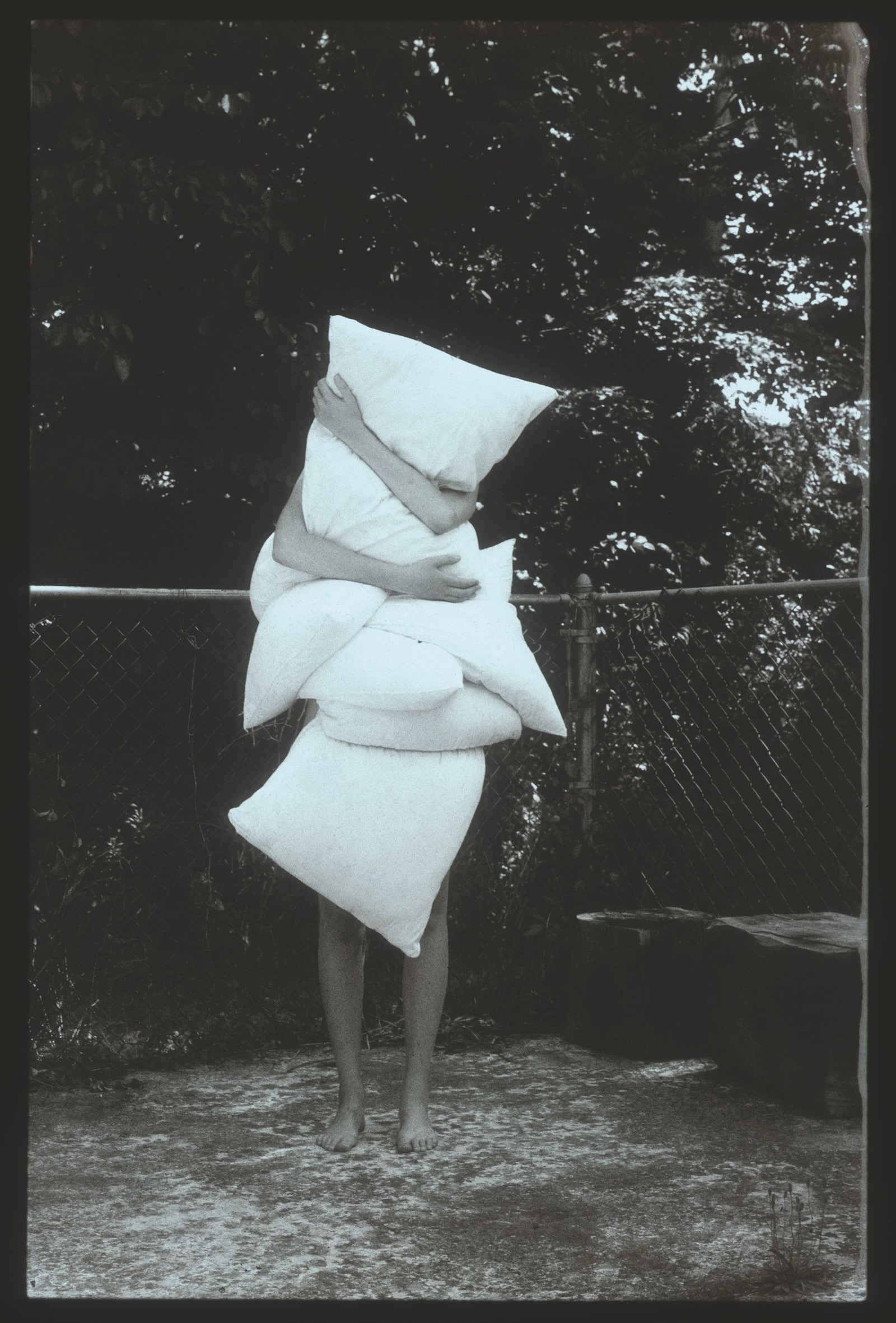

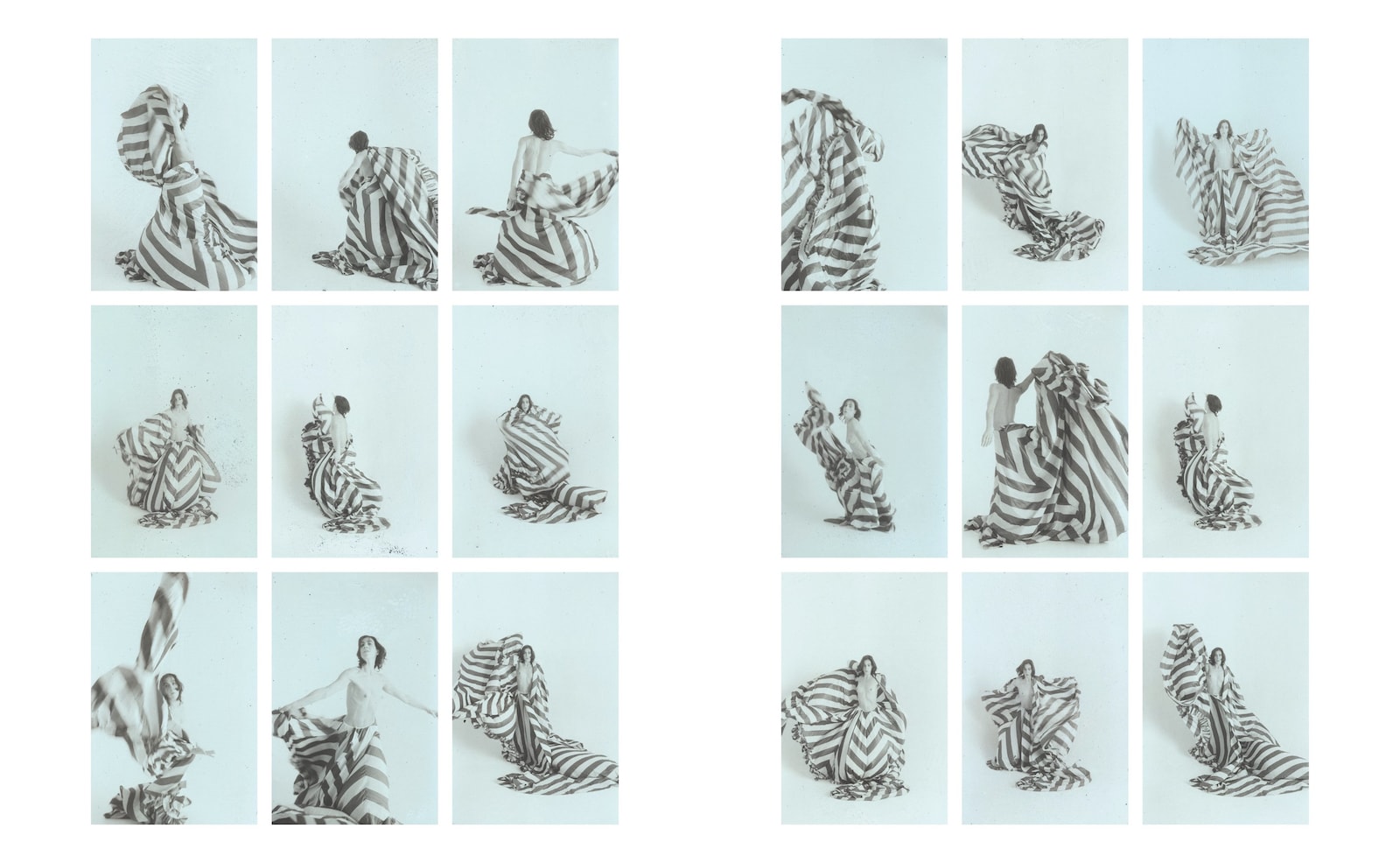

Lead ImageOut of Date: Pola Pan 1984-1996Photography by Mark Borthwick

There is a light that inflitrates the world when we create spaciousness – when we let life happen of its own volition. Mark Borthwick knows this light well: it leaks, flares and spills across his photographs. He has always embraced errors as apertures, reminders that the most revealing moments are the ones never planned.

If his new book is titled Out of Date – a reference to Pola Pan, a now-extinct 35mm black-and-white Polaroid film, that he used to photograph Paris and New York throughout the 1980s and 90s – it is perhaps more fitting to understand it as beyond date, beyond time: his photography and poetry forming a portal along the lemniscate of life. “You learn that because you document the same things over the years, everything you love, you’re actually just documenting a mirror image of yourself,” he says.

Borthwick has always lived in the blind spot between real life and its hallucinations. Raised in the English countryside, he sought refuge in the forest, guided by light, voices, fairies – the first shimmers of the spiritual world that plant medicine would reopen decades later. Through them, he learnt that meaning isn’t sought out through thought, but felt through instinct: through attention, through listening.

In the following conversation, the photographer, poet and musician shares his reflections on time, presence, creativity and the universe that reveals itself when you make space for it.

Madeleine Rothery: I’ve been thinking about time recently – how Western culture insists on linearity – yet how letting go of that opens everything up. And your book does just that: it looks back across time yet is very much you now.

Mark Borthwick: Absolutely. We’re confined by this notion of time, but we’re also aware – if we allow ourselves – that we can function outside it. There’s a simplicity in knowing that we are the creators of our own time and that we can create within that realm. Ask yourself: what are you paying attention to in the first place? And then pay attention to this incredible gift we’re given every single day.

MR: I’ve started to realise that the less I plan to do, the more I get done.

MB: And that makes a lot of sense. We waste so much time thinking about things when it’s so much easier to just do them. So, you follow your instinct and allow a space for things to happen upon their own volition.

I don’t do fashion shoots very often, but when I do, I never think about them beforehand. Because when I arrive, I’m excited, and something magical happens – something completely unexpected – and that creates an energy [that] the whole day runs off. If I knew what I was doing beforehand, I wouldn’t be open to the magic. Things always happen that you can’t control.

I’ve recently started doing talks, and they’ll say, “We’d love to speak beforehand about what we want to cover.” And I say, “Wait, please, I don’t want to know anything!” I’m not a thinker; I’m a doer. Knowing what we’re going to talk about or having to prepare … it abolishes solitude.

“Go inward. That’s where the vocabulary of your work already lives” – Mark Borthwick

MR: Do you think photography is a way of listening?

MB: I think photography is an incredibly beautiful way of listening – a way of engaging with the whole. It slows time down. It instils a sense of presence. It captures spirit. Everyone has different eyes, of course. I can only speak from mine. I’ve never studied photography, never researched it, never spent much time looking at it. I’m overwhelmed enough by my own senses – by feeling, by instinct. There’s always been this little mystical spark that guides me toward creation. I never really look through the lens of the camera, the camera is here – to the side of my head – because my eyes are just so besotted by what’s in front of me.

Fashion photography is just one small part of that. Most of my photographs were of my children as they grew, and I never shared them because that world felt too personal, too sacred. The same with nature. I’ve shared small glimpses over the years, but most of it has never been seen.

MR: So why did you choose to share these photos now?

MB: I was woken up by doing plant medicine. I’d never planned not to share any of this work – I’d simply never thought about it. I’m not ambitious in that sense. I never felt, “I must show this, I must get this gallery.” I’ve always had a lifetime of time in front of me.

When my children were born, something miraculous happened. I didn’t have a close relationship with my own father, and I know that we have this innate way of repeating our parents, but my spiritual guides took me under their wings. So, when Bibi [Borthwick’s daughter] arrived, I put photography aside and just raised my kids. That became the most beautiful time of my life.

I documented every single step. Yet at that time, I was aware that there were so many great photographers whose body of work revolved around that. But I decided I’m telling this story in my own personal way – and I was already telling so many other stories through my fashion work – that I just thought “these are the stories of one’s life, let’s give them space, and one day I’ll publish that book.” Less is more for me. If I did too many stories a year, I’d only repeat myself.

MR: I know what you mean. When I read back on my old writing, even though so much has changed, I still see myself.

MB: Exactly. When I compiled the text for the Pola Pan book – all my writing from 1976 to 1996 – I saw that nothing really changed. The mistakes, the naivety, the awkwardness … they all have meaning because they’re portals back to who you were then. It would be so silly to say “this is good” or “this is bad,” because I’m not trying to be a “great writer” or “poet.” This is just my way of expressing myself … a form of letting go. Words have their own life: they morph, shift, carry light. And some words stay with you for decades.

MR: There’s something comforting about everyone sharing the same words and somehow making them personal.

MB: Words are there to charm us. And nothing is really “ours” anyway. I once taught at Yale, and a student was teased for “copying” me because he photographed trees. But I didn’t create the tree – Mother Nature did. If he spends 20 years photographing trees, that universe becomes his.

Everything comes from somewhere. Pay attention to what you vibrate with – abandoned buildings, oceans, city walks, wilderness, films, animals. Christmas lights! Choice is a powerful tool. Go inward. That’s where the vocabulary of your work already lives.

MR: There’s pressure now to make things complex, as if complexity equals value.

MB: Being human is complex enough. Choose simplicity. Choose feeling. Choose the universe that’s already inside you. And on that note, I think it’s time we go dance!

Out of Date: Pola Pan 1984-1996 by Mark Borthwick is published by Rizzoli and is out now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageOut of Date: Pola Pan 1984-1996Photography by Mark Borthwick

There is a light that inflitrates the world when we create spaciousness – when we let life happen of its own volition. Mark Borthwick knows this light well: it leaks, flares and spills across his photographs. He has always embraced errors as apertures, reminders that the most revealing moments are the ones never planned.

If his new book is titled Out of Date – a reference to Pola Pan, a now-extinct 35mm black-and-white Polaroid film, that he used to photograph Paris and New York throughout the 1980s and 90s – it is perhaps more fitting to understand it as beyond date, beyond time: his photography and poetry forming a portal along the lemniscate of life. “You learn that because you document the same things over the years, everything you love, you’re actually just documenting a mirror image of yourself,” he says.

Borthwick has always lived in the blind spot between real life and its hallucinations. Raised in the English countryside, he sought refuge in the forest, guided by light, voices, fairies – the first shimmers of the spiritual world that plant medicine would reopen decades later. Through them, he learnt that meaning isn’t sought out through thought, but felt through instinct: through attention, through listening.

In the following conversation, the photographer, poet and musician shares his reflections on time, presence, creativity and the universe that reveals itself when you make space for it.

Madeleine Rothery: I’ve been thinking about time recently – how Western culture insists on linearity – yet how letting go of that opens everything up. And your book does just that: it looks back across time yet is very much you now.

Mark Borthwick: Absolutely. We’re confined by this notion of time, but we’re also aware – if we allow ourselves – that we can function outside it. There’s a simplicity in knowing that we are the creators of our own time and that we can create within that realm. Ask yourself: what are you paying attention to in the first place? And then pay attention to this incredible gift we’re given every single day.

MR: I’ve started to realise that the less I plan to do, the more I get done.

MB: And that makes a lot of sense. We waste so much time thinking about things when it’s so much easier to just do them. So, you follow your instinct and allow a space for things to happen upon their own volition.

I don’t do fashion shoots very often, but when I do, I never think about them beforehand. Because when I arrive, I’m excited, and something magical happens – something completely unexpected – and that creates an energy [that] the whole day runs off. If I knew what I was doing beforehand, I wouldn’t be open to the magic. Things always happen that you can’t control.

I’ve recently started doing talks, and they’ll say, “We’d love to speak beforehand about what we want to cover.” And I say, “Wait, please, I don’t want to know anything!” I’m not a thinker; I’m a doer. Knowing what we’re going to talk about or having to prepare … it abolishes solitude.

“Go inward. That’s where the vocabulary of your work already lives” – Mark Borthwick

MR: Do you think photography is a way of listening?

MB: I think photography is an incredibly beautiful way of listening – a way of engaging with the whole. It slows time down. It instils a sense of presence. It captures spirit. Everyone has different eyes, of course. I can only speak from mine. I’ve never studied photography, never researched it, never spent much time looking at it. I’m overwhelmed enough by my own senses – by feeling, by instinct. There’s always been this little mystical spark that guides me toward creation. I never really look through the lens of the camera, the camera is here – to the side of my head – because my eyes are just so besotted by what’s in front of me.

Fashion photography is just one small part of that. Most of my photographs were of my children as they grew, and I never shared them because that world felt too personal, too sacred. The same with nature. I’ve shared small glimpses over the years, but most of it has never been seen.

MR: So why did you choose to share these photos now?

MB: I was woken up by doing plant medicine. I’d never planned not to share any of this work – I’d simply never thought about it. I’m not ambitious in that sense. I never felt, “I must show this, I must get this gallery.” I’ve always had a lifetime of time in front of me.

When my children were born, something miraculous happened. I didn’t have a close relationship with my own father, and I know that we have this innate way of repeating our parents, but my spiritual guides took me under their wings. So, when Bibi [Borthwick’s daughter] arrived, I put photography aside and just raised my kids. That became the most beautiful time of my life.

I documented every single step. Yet at that time, I was aware that there were so many great photographers whose body of work revolved around that. But I decided I’m telling this story in my own personal way – and I was already telling so many other stories through my fashion work – that I just thought “these are the stories of one’s life, let’s give them space, and one day I’ll publish that book.” Less is more for me. If I did too many stories a year, I’d only repeat myself.

MR: I know what you mean. When I read back on my old writing, even though so much has changed, I still see myself.

MB: Exactly. When I compiled the text for the Pola Pan book – all my writing from 1976 to 1996 – I saw that nothing really changed. The mistakes, the naivety, the awkwardness … they all have meaning because they’re portals back to who you were then. It would be so silly to say “this is good” or “this is bad,” because I’m not trying to be a “great writer” or “poet.” This is just my way of expressing myself … a form of letting go. Words have their own life: they morph, shift, carry light. And some words stay with you for decades.

MR: There’s something comforting about everyone sharing the same words and somehow making them personal.

MB: Words are there to charm us. And nothing is really “ours” anyway. I once taught at Yale, and a student was teased for “copying” me because he photographed trees. But I didn’t create the tree – Mother Nature did. If he spends 20 years photographing trees, that universe becomes his.

Everything comes from somewhere. Pay attention to what you vibrate with – abandoned buildings, oceans, city walks, wilderness, films, animals. Christmas lights! Choice is a powerful tool. Go inward. That’s where the vocabulary of your work already lives.

MR: There’s pressure now to make things complex, as if complexity equals value.

MB: Being human is complex enough. Choose simplicity. Choose feeling. Choose the universe that’s already inside you. And on that note, I think it’s time we go dance!

Out of Date: Pola Pan 1984-1996 by Mark Borthwick is published by Rizzoli and is out now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.