Rewrite

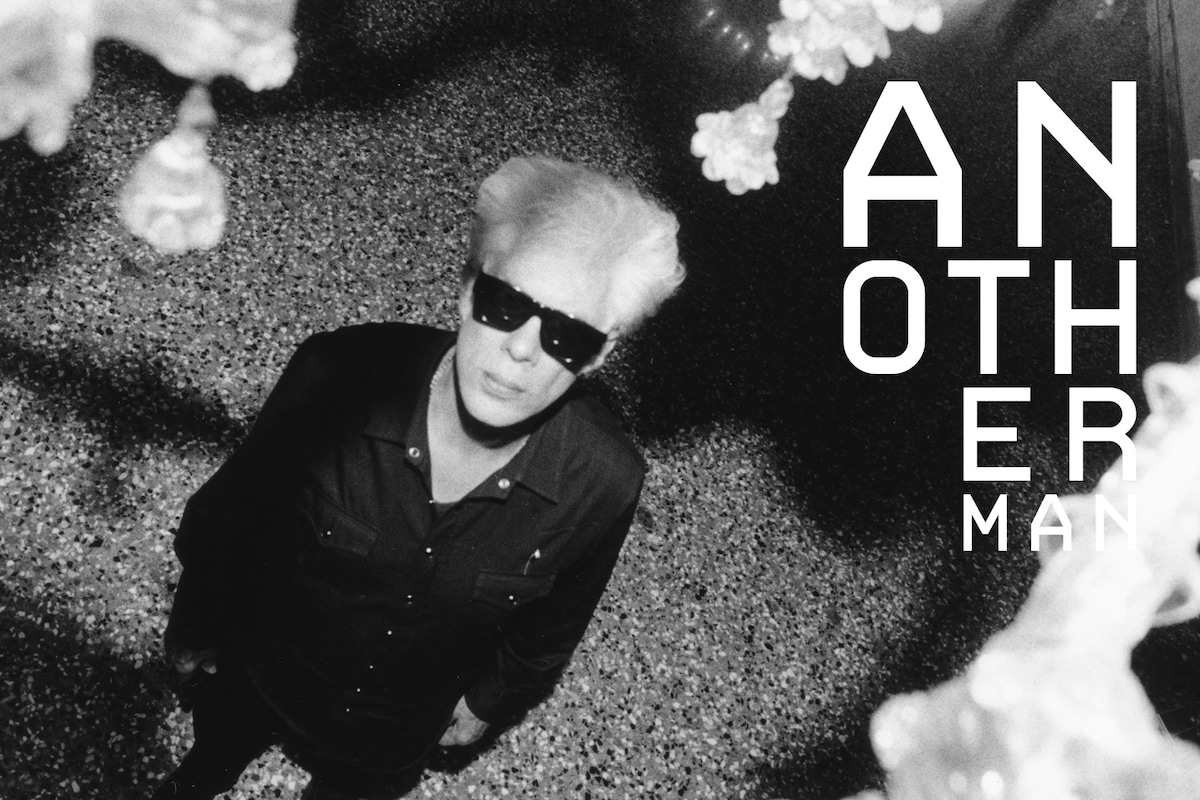

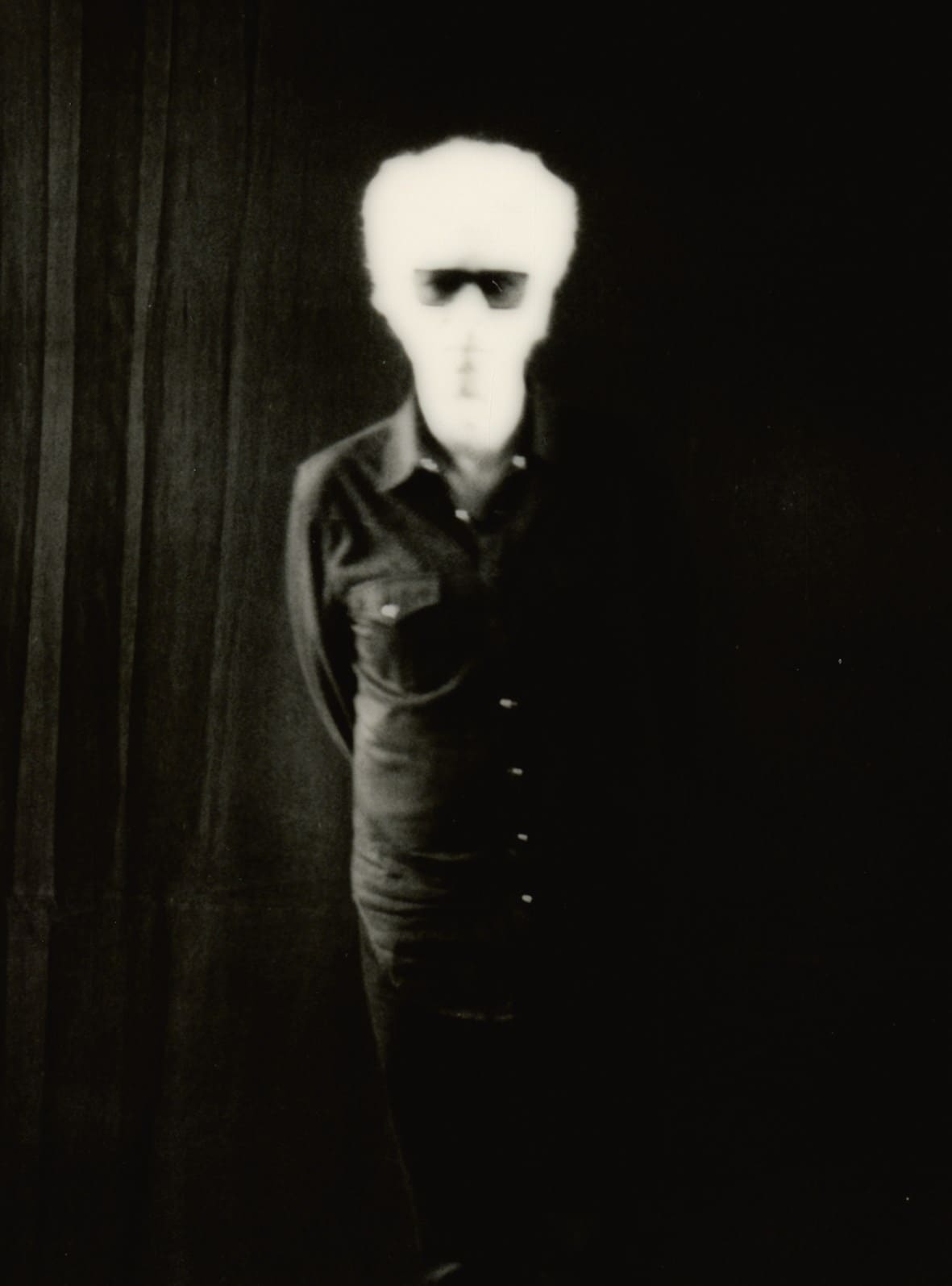

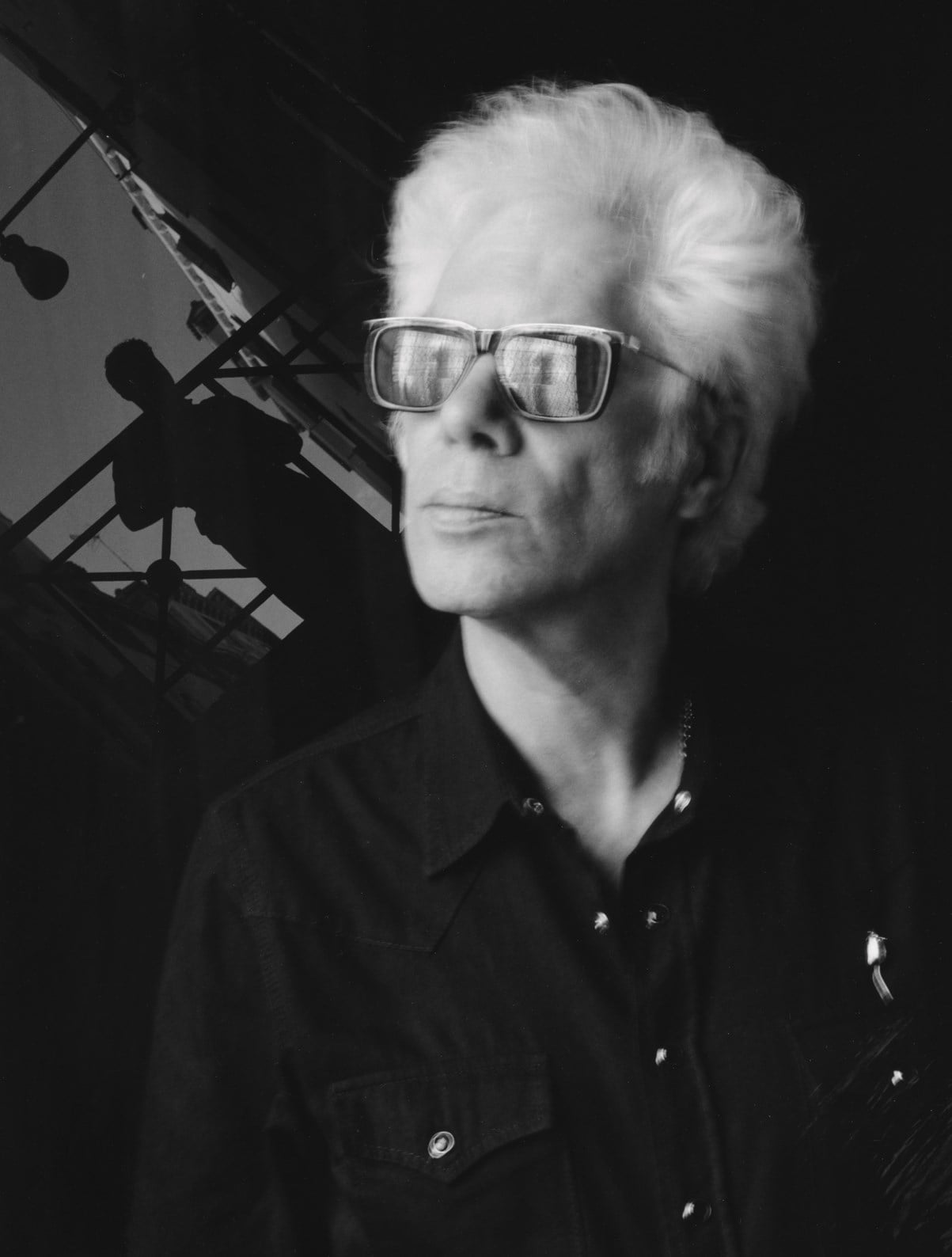

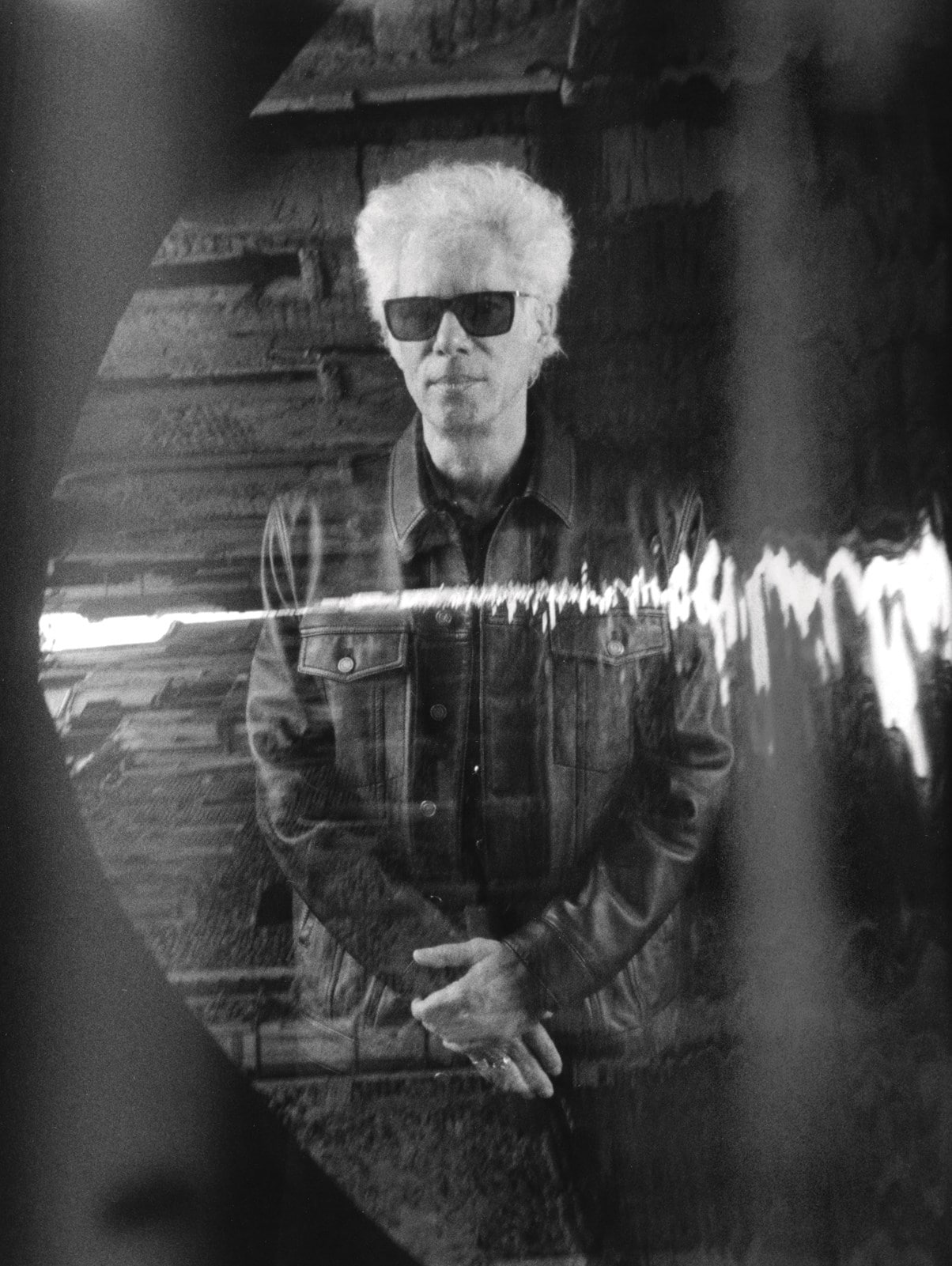

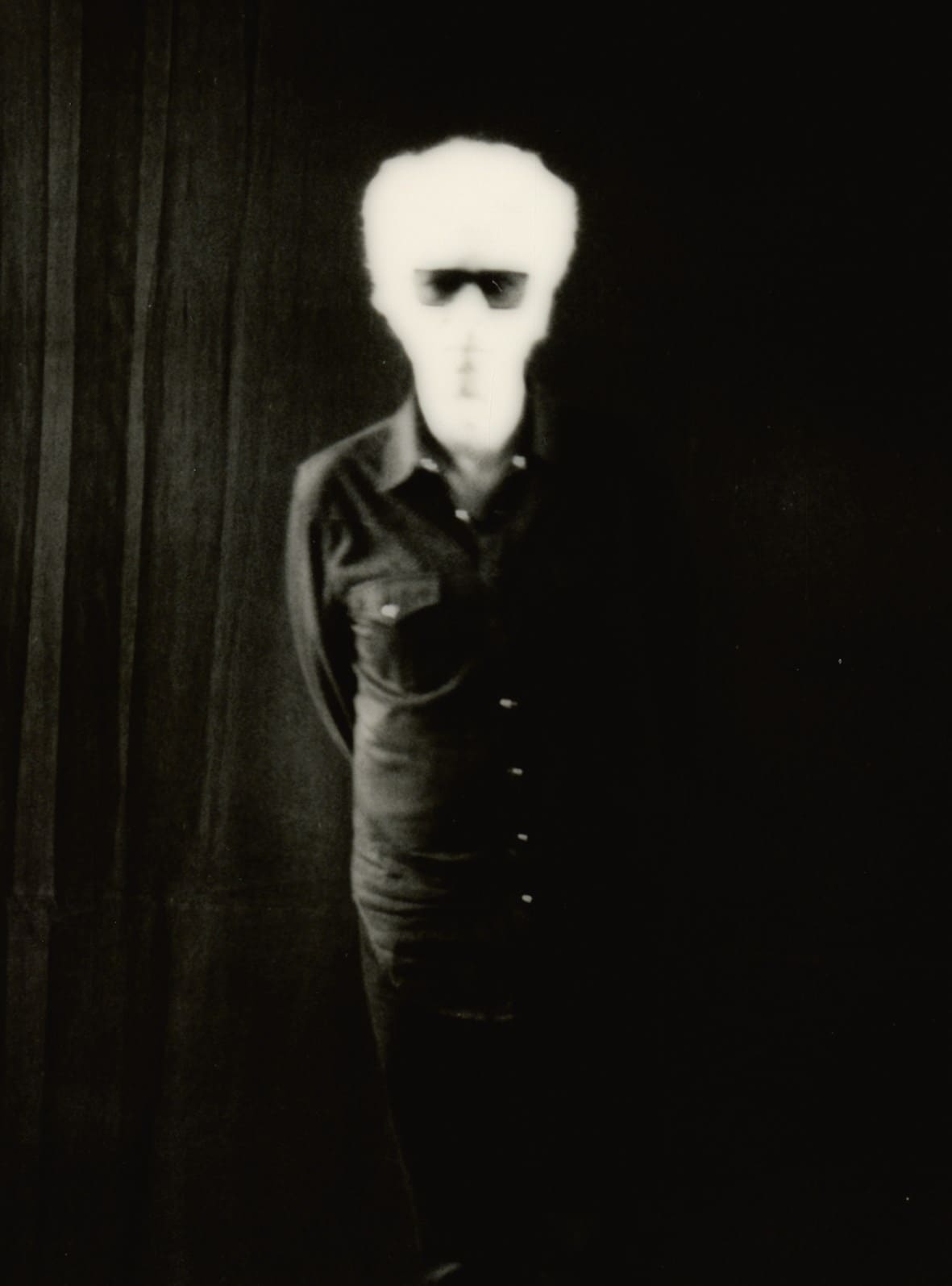

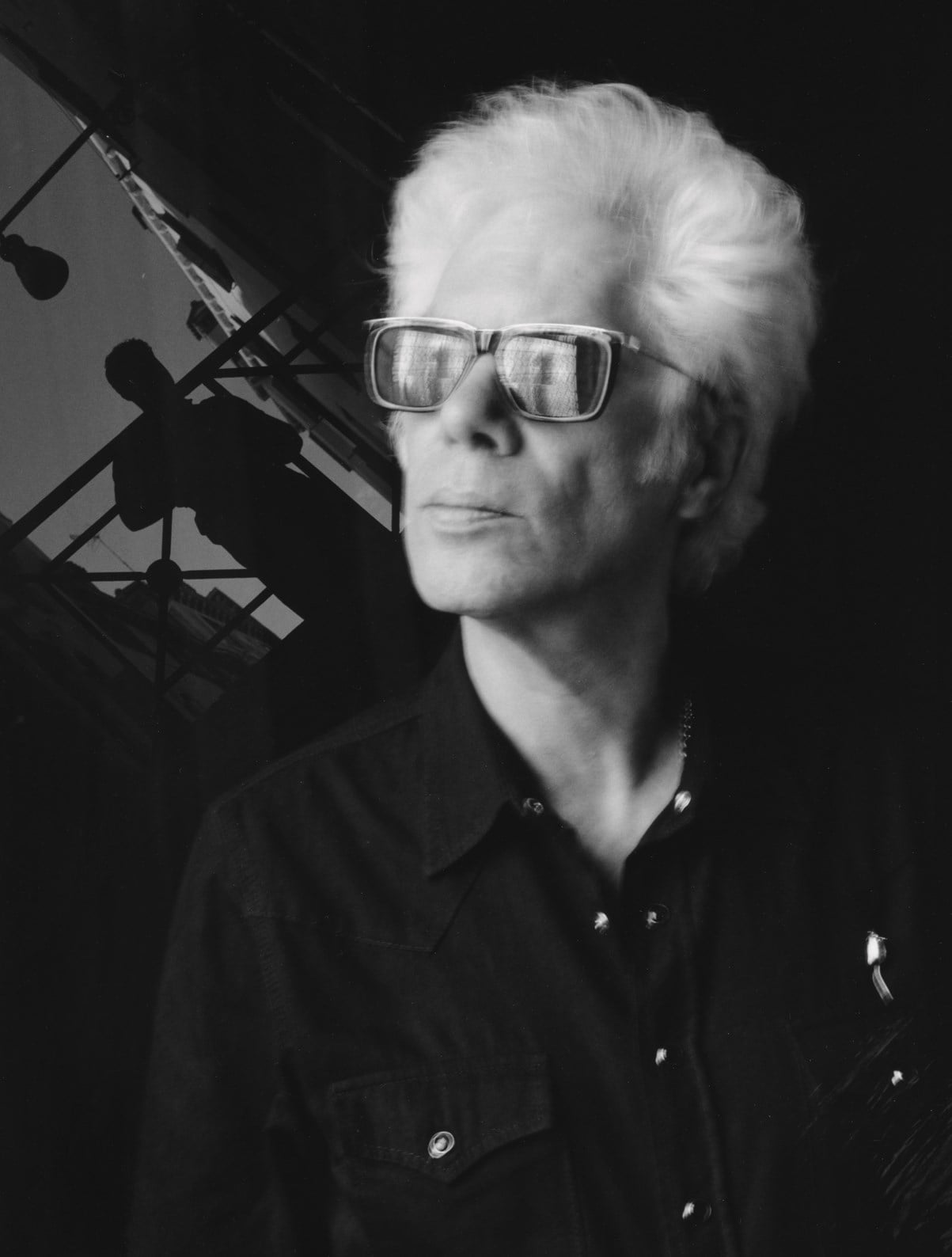

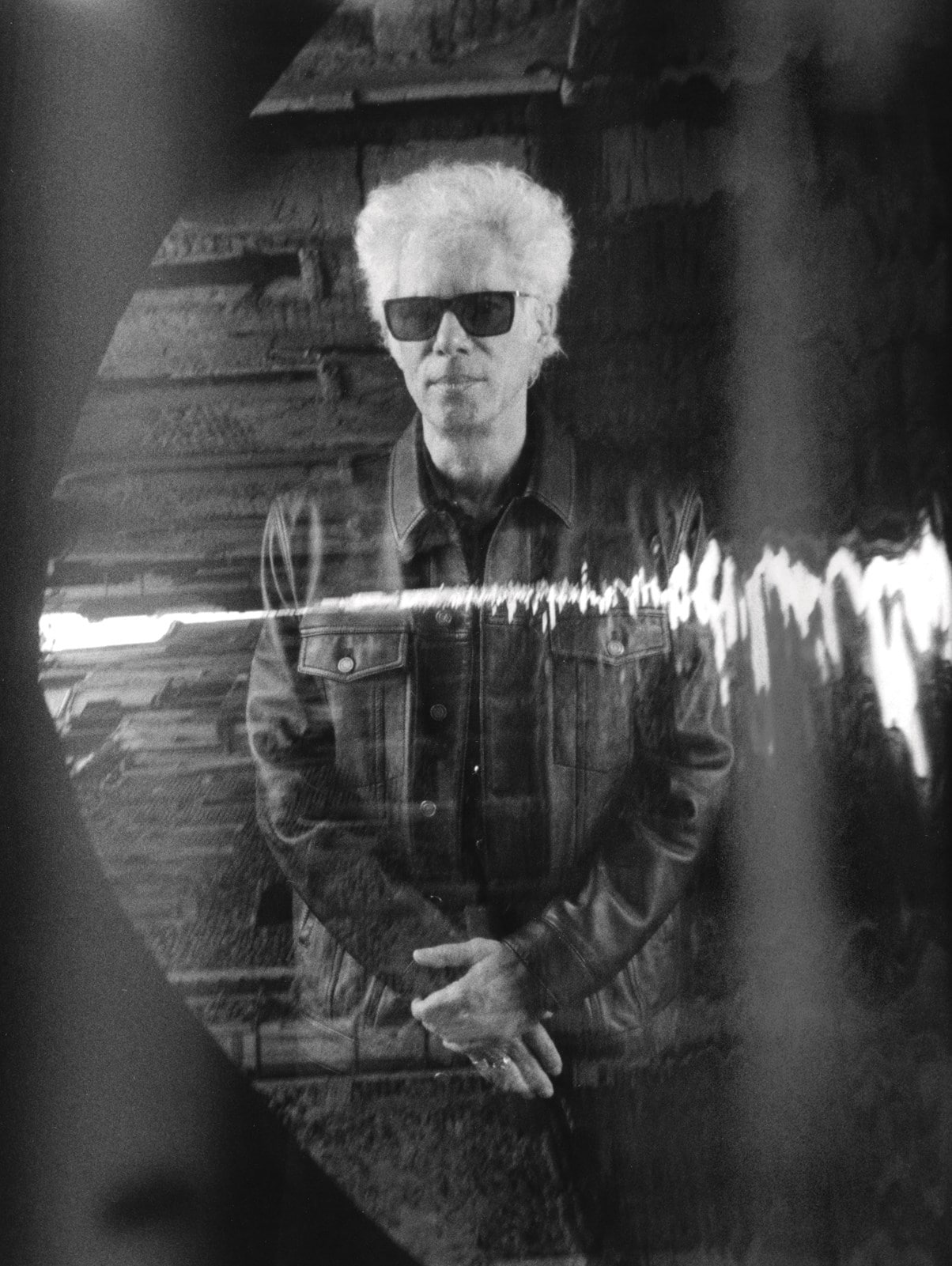

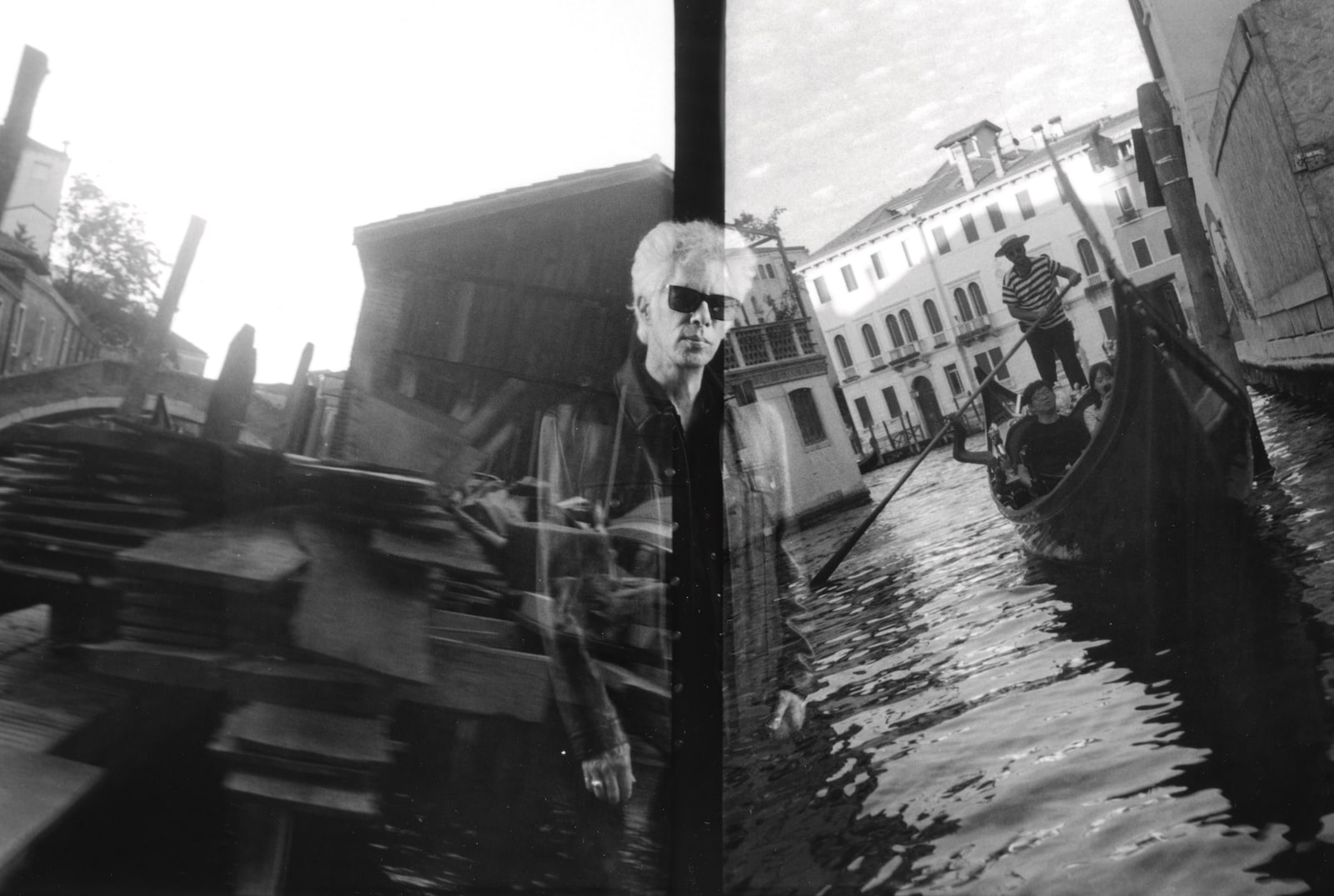

Lead ImageJim Jarmusch is wearing Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from October 30. Pre-order here.

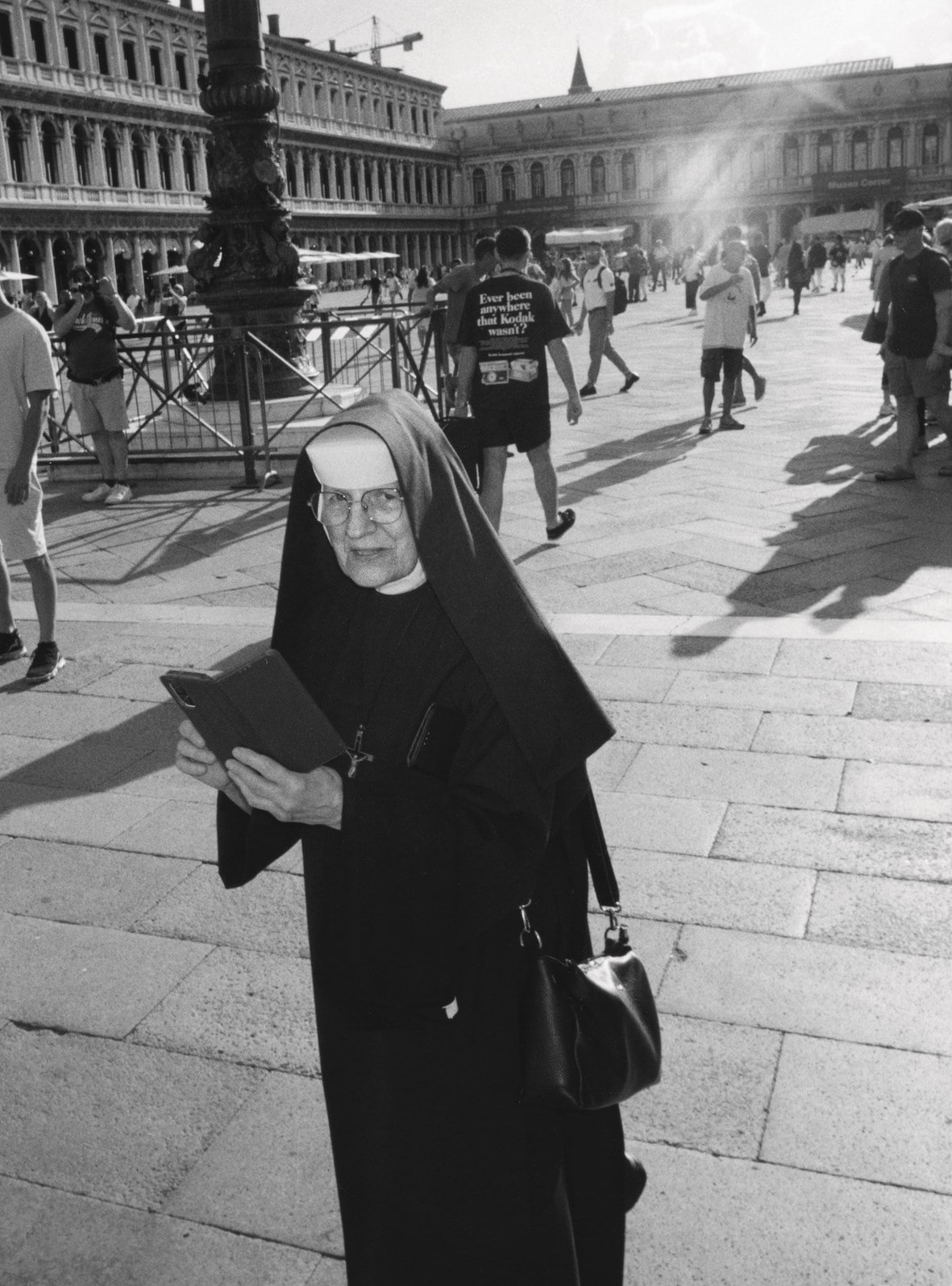

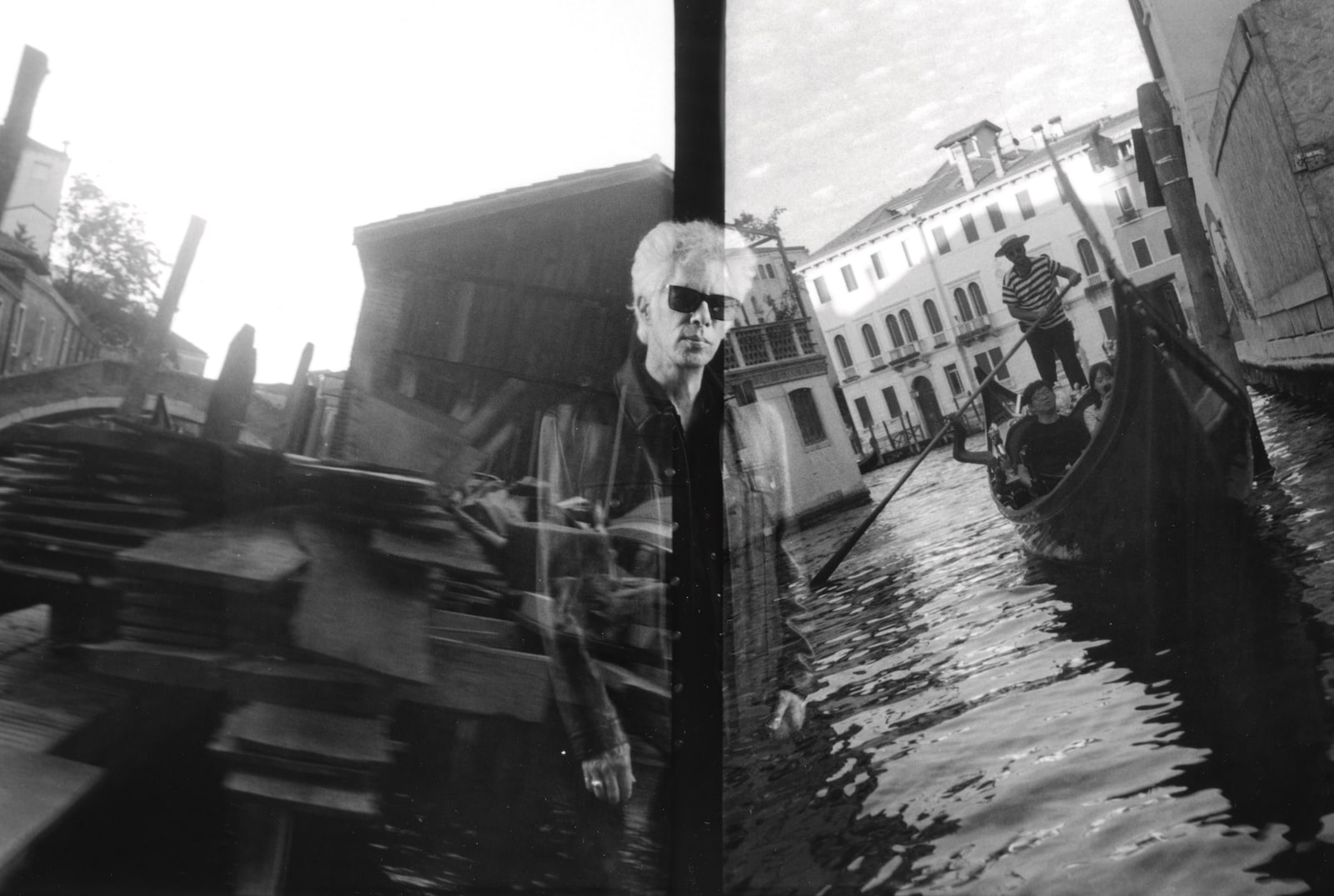

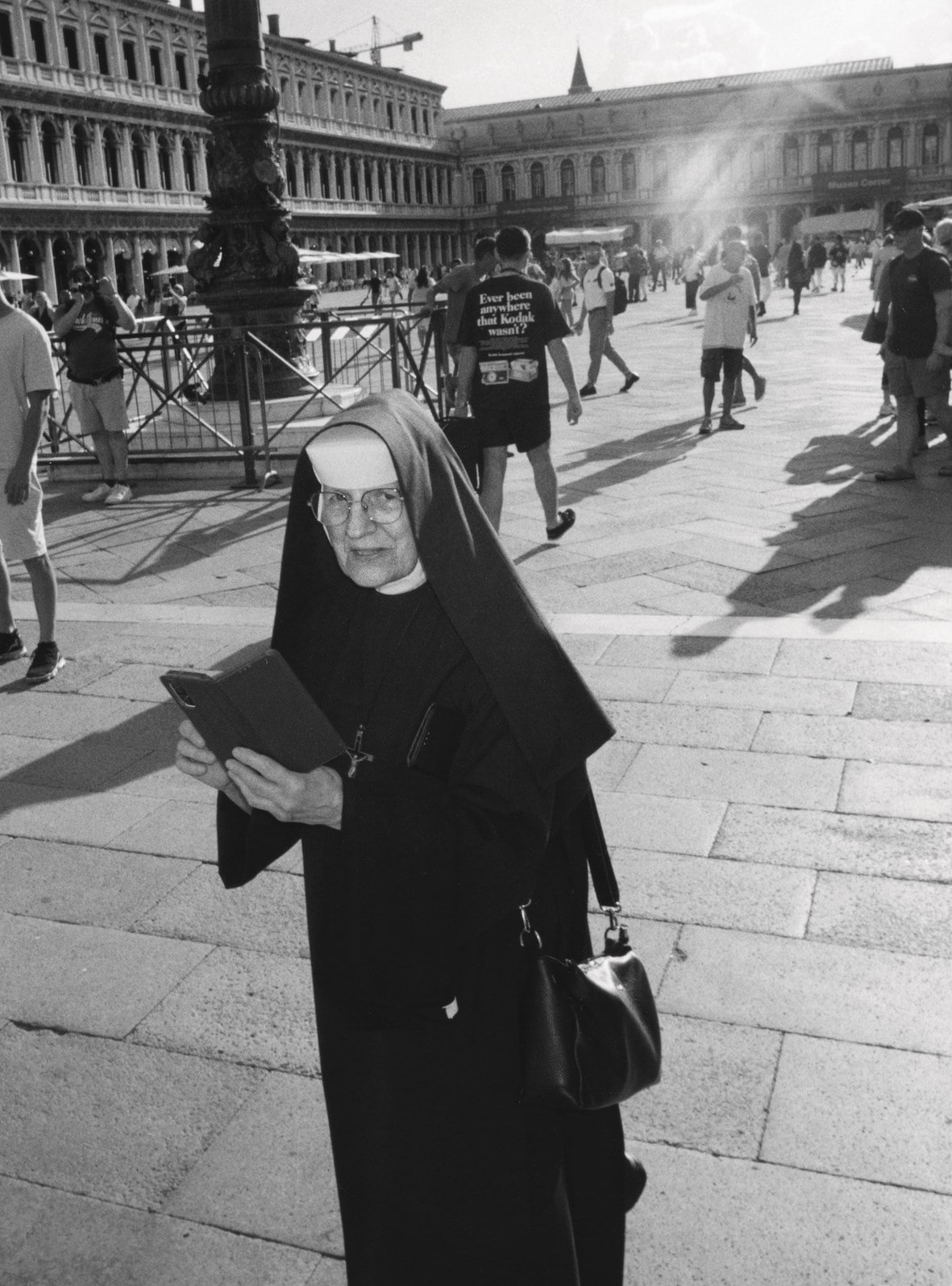

We meet Jim Jarmusch on Venice’s grand canal, in a 15th-century gothic palazzo – all chandeliers, marble floors and the ghosts of past guests who ranged from Proust to Verdi. It’s the kind of bewitched location the erudite, centuries-old vampires in the filmmaker’s Only Lovers Left Alive might appreciate, with the exception of the Italian sunshine, glinting off green lagoon waters outside. Jarmusch is in the floating city for the premiere of his bittersweet jewel of a film, Father Mother Sister Brother, a beautifully paced, wise, and minutely observed triptych that dwells on the complex interplay between parents and their grown-up children. “It’s anti-action,” says the uncompromising director, with his distinctive, laconic delivery. “It doesn’t have any drama really: no violence, no sex, no nudity, no agenda.” He is three days away from winning the festival’s Golden Lion for it.

Jarmusch is a Johnny Cash kind of dresser, in shades and in black, aside from the tiny gold stickpin mouse on his lapel, and a polkadot patterned notebook in his hands. “I wrote some things in here half asleep…” he explains, “a song called New York Jesus, about Lou Reed.” He writes all his scripts by hand too, in notebooks stashed around his home in the Catskills, and his films feel similarly handmade – closer to paintings, or perhaps the poetry he studied as a student under Kenneth Koch at Columbia. His camera finds the small details and in between moments – the coffee-and-cigarette breaks, taxi rides and throwaway asides that might die on the cutting-room floor in more conventional hands. “Have you seen Buster Keaton’s 1925 film Go West? He sells all his belongings for a train ticket and one sandwich. The whole trip is about the sandwich. How minimal could you get?” he says, delighted. Meanwhile he’ll sometimes skip the drama many directors might consider the point – bypass a prison-escape entirely, say, in swampy 1986 three-hander, Down By Law, which starred longtime comrade Tom Waits.

Almost 40 years after that film, it’s Waits who opens the first chapter of Jarmusch’s latest, as a bohemian father puttering around his weather-beaten New Jersey home on the occasion of a rare visit by his two, much straighter children (Adam Driver and Mayim Bialik). Filled with mordant humour, it sets the course for the film’s meditation on the roles we play among those who share our DNA, the dissonance and fractured communication, the bonds and memories that endure. In Dublin, Charlotte Rampling invites her two daughters (Vicky Krieps and Cate Blanchett) for an awkward annual ritual of tea and cakes, the stilted surface conversation sporadically breaking to reveal glimpses of the inner lives bubbling beneath. Two French-American twins (Luka Sabbat and Indya Moore) grapple with their late parents’ legacy in the final third, a dreamy, beguiling closer set in Paris that envelopes its viewer in the soft melancholy of a Nico song. Between all three, Jarmusch weaves variations and echoes, which extend to his characters’ subtly colourcoordinated clothes, courtesy of Anthony Vaccarello and Saint Laurent, who also co-produced the film.

Since his earliest movies – Permanent Vacation’s tale of a Charlie-Parker-obsessed drifter, shot around a weed-ridden Lower East Side; the grimy, deadpan Stranger Than Paradise, made with leftover film stock gifted by Wim Wenders – Jarmusch has centred the misfits and outsiders, whether bus-driver poets or zombies, conflicted hitmen or Japanese tourists lugging a suitcase around Memphis in search of the spirit of Elvis. The now 72-year-old has remained an inveterate outsider himself, choosing creative control over a studio paycheck and carving his own, idiosyncratic path, an attitude that might have been forged amid the nocturnal life of Downtown New York, where he arrived fresh from America’s industrial heartland – Cuyahoga Falls, a suburb of Akron, Ohio – in the 1970s. The rackety, near bankrupt city he found had blackouts, widespread arson and a prowling serial killer, Son of Sam, but also rock-bottom rents, a pinballing creative scene and a DIY sense of possibility – the Mudd club and CBGBs, where Jarmusch played with his band The Del-Byzanteens, prized expression over technical skill. The director’s love of music continues to run parallel to and inform his filmmaking today, encompassing his current musical outfit, SQÜRL, the documentaries he has made on Crazy Horse and the Stooges, and the singular, spellbinding rhythm of his films.

In his company, it’s easy to see why the cosmopolitan circle of accomplices drawn into Jarmusch’s orbit tend to return again and again, becoming friends as well as collaborators. He is generous and interested, with a magpie-mind for details esoteric and wide-ranging (his “special thanks” credits are always a rewarding read, spanning Joe Strummer to Mary Shelley). Rather like his films, a conversation with Jarmusch takes mercurial detours into unexpected territory. “Yeah,” he says, “but tangents are what it’s all about, man.”

Hannah Lack: Can you talk about the process of writing Father Mother Sister Brother? Do you gather ideas in notebooks like that one you’re holding?

Jim Jarmusch: Yeah, I gather little details and disparate things until they start to form a picture. One thing I do as an exercise before I begin writing is read some prose by Marguerite Duras. She has a beautiful way of reducing things – “She responded with a negative gesture.” I always use Duras to clear my head, try to get a voice close to her style. With my film Paterson I carried ideas for 20 years. This last one came pretty fast, I wrote it in three weeks. And then it’s connect-the-dots – you know those drawings where you don’t know what it’s going to be quite yet? The script is not literature; it’s a map. To me, shooting a film is gathering the things from which you will make the film in the cutting room. I don’t have storyboards, like Hitchcock, very precise. I follow my intuition. But it’s not totally random. This film has a three-part structure that cannot be separated. I worked very hard to have an accumulation of things emotionally. If you watched one without the others, I would be mortified.

HL: You’ve cast many regular collaborators, including Tom Waits. What are the creative pleasures of working with someone like Tom over such a long stretch now?

JJ: Yes, Cate Blanchett and Adam Driver too – you get a kind of shorthand. Tom’s particular, because we’ve been close friends for many years and have had a lot of very strange experiences together.

HL: Can you tell me one?

JJ: Oh gosh, where would I begin? Well, when we were shooting Down By Law, we borrowed this black Jaguar for a few scenes. And at night Tom would say, “Jim, let’s go in the production office, get the keys to the Jag and drive through New Orleans all night.” Which we did, three nights in a row, just Tom and me. We had one cassette in the car, which was Julie London singing Cry Me a River. The third night I said, “Tom, we only got this one song…” He said, “Jim, what more do we need, man?”

HL: Where did you two first meet?

JJ: 1985, at a party that Jean-Michel Basquiat had at Mr. Chow in New York. I knew Jean-Michel, and Andy Warhol was there. Tom and I ended up going out all night to various venues, to Danceteria… we’ve been friends ever since, done five films together now.

“You cannot bludgeon a film into the preconceived thing. You bring what you gathered and then it tells you what it wants” – Jim Jarmusch

HL: You’ve worked with many musicians on scores – John Lurie, Neil Young, RZA… but this one you wrote yourself.

JJ: Yeah I’ve done it a few times. I make a playlist while I’m writing and it informs the end music. With Ghost Dog, I bought all the DJ vinyl of Wu-Tang, which on the B-side had just the instrumental beats. I did a similar thing for Dead Man, where I took the Neil Young/Crazy Horse wilder stuff and patched it together with instrumental sections from Zuma and On the Beach. Oddly for Father Mother I had no music in my head. The music is very spare. With my film Paterson, making the music with Carter Logan wasn’t hard because it’s a central character and his perception of the world. Father Mother has no central character, no viewpoint. So the music ended up being minimal, little cloud formations here and there. I think the film wanted that. I’ve learned that in the editing room, you must listen to what the film wants to be. You cannot bludgeon it into the preconceived thing. You bring what you gathered and then it tells you what it wants. Like when I write good dialogue, I’m hearing the characters talk. It’s kind of weird. They start talking and I write it down.

HL: Is there a particular place you like to go to create your music or do your writing?

JJ: Yes. I have a place up in the Catskill Mountains. It’s quite secluded, very wooded, no people around. A lot of bears, coywolves, birds and raccoons, and beautiful trees. I converted part of the garage into a little recording studio/art room, kind of a teenager’s dream studio. I have my instruments and amplifiers and microphones, and I write there too. But I write all around my place upstate, outside. I write by hand, never on a keyboard. I’m always moving with my notebooks.

HL: I think people imagine you as a city person…

JJ: Well, I love cities dearly. Most cities I fall in love with. Other people think, “Really? You like Baltimore?” New York is my city since I ran away from home at 17. And Paris is very important in my life. So those two are my real lovers. But my New York lover, she’s kind of pushing me away now. She gave me so much energy but now she’s cashing it in on me. But the history of New York is about change. When people say, “Oh, you should have been there in the eighties”–New York is always in flux and always about hustling and money. It’s just less interesting now because young people can’t afford to live there. Paris I got to on a student exchange year and I did not complete my studies because I discovered the Cinémathéque. That’s where I became obsessed with movies.

HL: Not as a kid in Akron, Ohio?

JJ: No, in Akron I saw monster movies. My mother, before she had children, was a movie reviewer for the Akron Beacon Journal, but she was more into Hollywood movies from the 40s and 50s. In Paris I saw films from all over the world, discovered ones that reflect this quiet style that Father Mother has – Ozu, Bresson, Carl Dreyer.

HL: Who were your mentors during those early years?

JJ: Robert Frank was a friend. And two American directors – Nick Ray, I was his ‘assistant’, in quotes, the last two years of his life. I love his films. Johnny Guitar is such a Brechtian Western. You know Nick studied architecture with Frank Lloyd Wright and he designed the sets for it, but they look like cheesy ski lodges. It’s not supposed to be accurately a Western, they all have 60s haircuts. Sam Fuller (Shock Corridor, White Dog) was also a mentor, I hung out with him in Berlin, Paris, New York, LA and Brazil. And William Burroughs I met on the documentary Howard Brookner made about him, just the two of us were the crew. In New York, Burroughs was living in the ‘bunker’ on the Bowery, but we also went to these ghost towns in Colorado with him, and to London. Burroughs was very influential to me in other ways.

HL: In the collage art what do you do?

JJ: Yes. I used to sit with William sometimes when he worked on his scrapbooks, which was him finding juxtapositions in random things he’d find in the newspaper: “It says here: ‘Murdered man found in Kansas, the victim’s body was stuffed in a burlap bag.’ And here’s an advertisement for burlap, made in Oklahoma…” What a mind, my God. He should have been a secret agent. He could have been in the CIA – instead he was this countercultural subversive. One thing I loved that he said to me once: “Jim, we have no reason to assume these aliens are in any way benevolent.” But my real mentors too, are the New York School poets, because I studied with Kenneth Koch, David Shapiro, and Ron Padgett, who wrote the poems for Paterson. In Father Mother, the poet Anne Waldman is the mother you see in the photograph as Tom Waits’ wife. And Frank O’Hara is important because Frank had a manifesto in 1959 called personism, which basically said, you write the poem or make the painting to one person, to a lover or to a friend. I kind of always do that; I don’t want to proclaim to the world. With Father Mother I’m really not trying to say anything. I’m just trying to observe non-judgmentally the complexities of interrelations, in this case familial ones. But there’s no moral, there’s no lesson to be learned. That’s not my thing.

“I’ve always avoided Hollywood or anyone else telling me how to make my films” – Jim Jarmusch

HL: The variations and echoes between the three chapters feel very intricate. Did you let your actors play around with the language?

JJ: They’re all different. Like, Adam and Mayim are very precise actors. Tom needs a longer leash. The first day of shooting, Tom took me aside and said, “Jim, you hired two professional killers. What do I do?” I said, “Tom, we do our way. We know each other; you trust me?” “Yeah, otherwise I wouldn’t be here.” “So, this is going to be great.” I worked with Robert Mitchum for Dead Man and Mr. Mitchum does not improvise. Michael Wincott in Dead Man, I ended up letting him improvise every line because he’d come up with something better.

HL: In your last film, The Dead Don’t Die, you were dealing with zombies, bad weather… how did this shoot compare?

JJ: With The Dead Don’t Die, the financing was on my back about money all the time. Aesthetically, nobody interferes. I have full artistic control. But I would be getting calls about budget – it was very unpleasant. I didn’t want to make a film for four or five years because I didn’t want to go to hospital for the stress of making a movie. This is what I love doing and I’ve always avoided Hollywood or anyone telling me how to make my films. I have final cut, otherwise I don’t do it; I’m not doing this to make commercial films. So, Father Mother was a kind of study in observational filmmaking. It’s anti-action. It doesn’t have any drama really: no violence, no sex, no nudity, no agenda. It’s very cumulative, very delicate. But it was no easier to make. It’s easier to make zombies come out of their graves than to be watching Cate Blanchett’s eyelid flicker. What’s the quote? It takes a lot of effort to make something look effortless. I’m very meticulous about details but once the film is done and I’ve seen it–not at a festival, but with a real audience who don’t know I’m there – after that I never see it again. My French crew on this was fantastic though, a 65 percent female crew, who worked so hard and had an ashtray glued to the camera cart because they’re French and they need to smoke. I’m getting them all back if I can for the next.

HL: Do you speak French?

JJ: I do. Paris and French culture have always been very important to me.

HL: Do you always have projects ongoing?

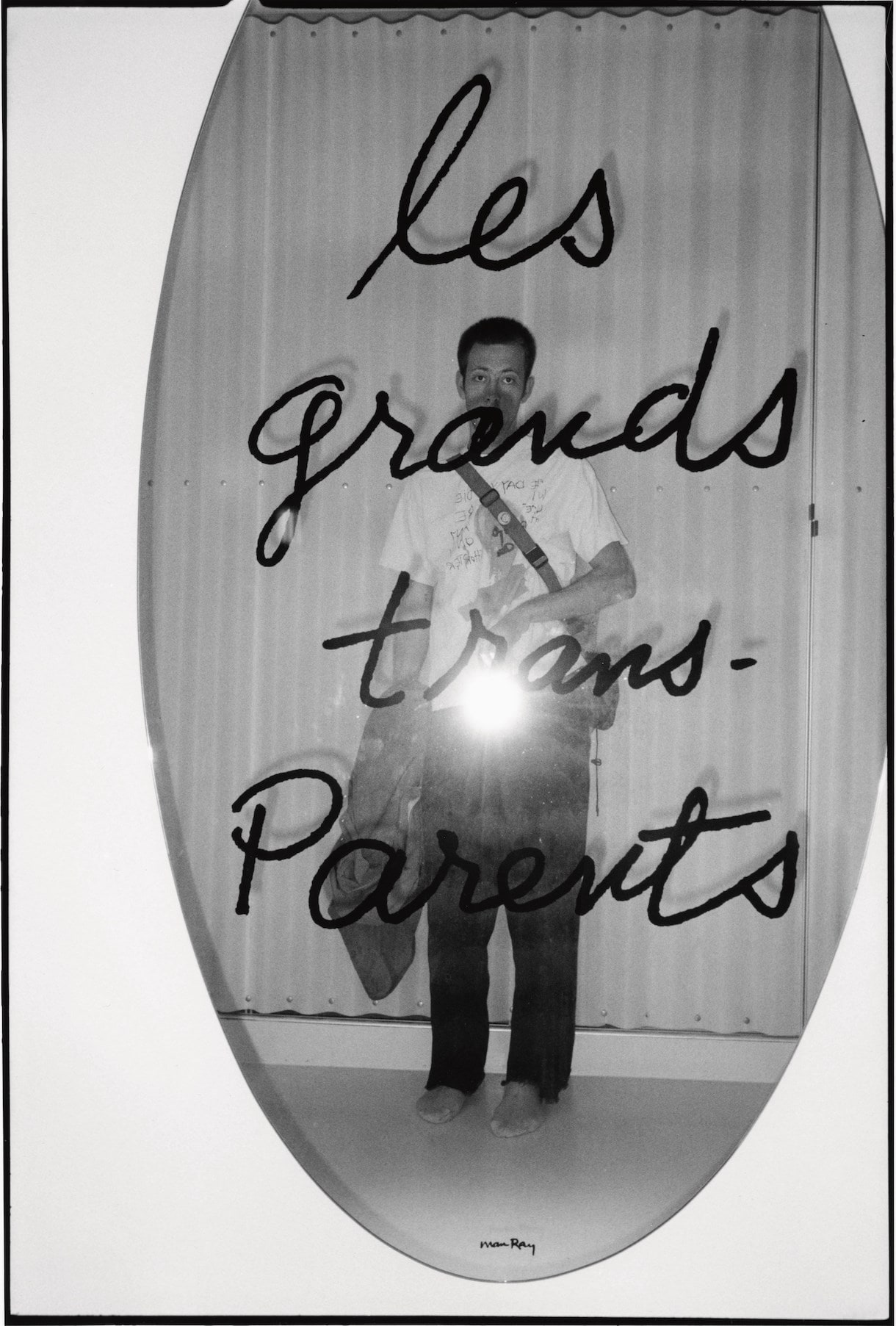

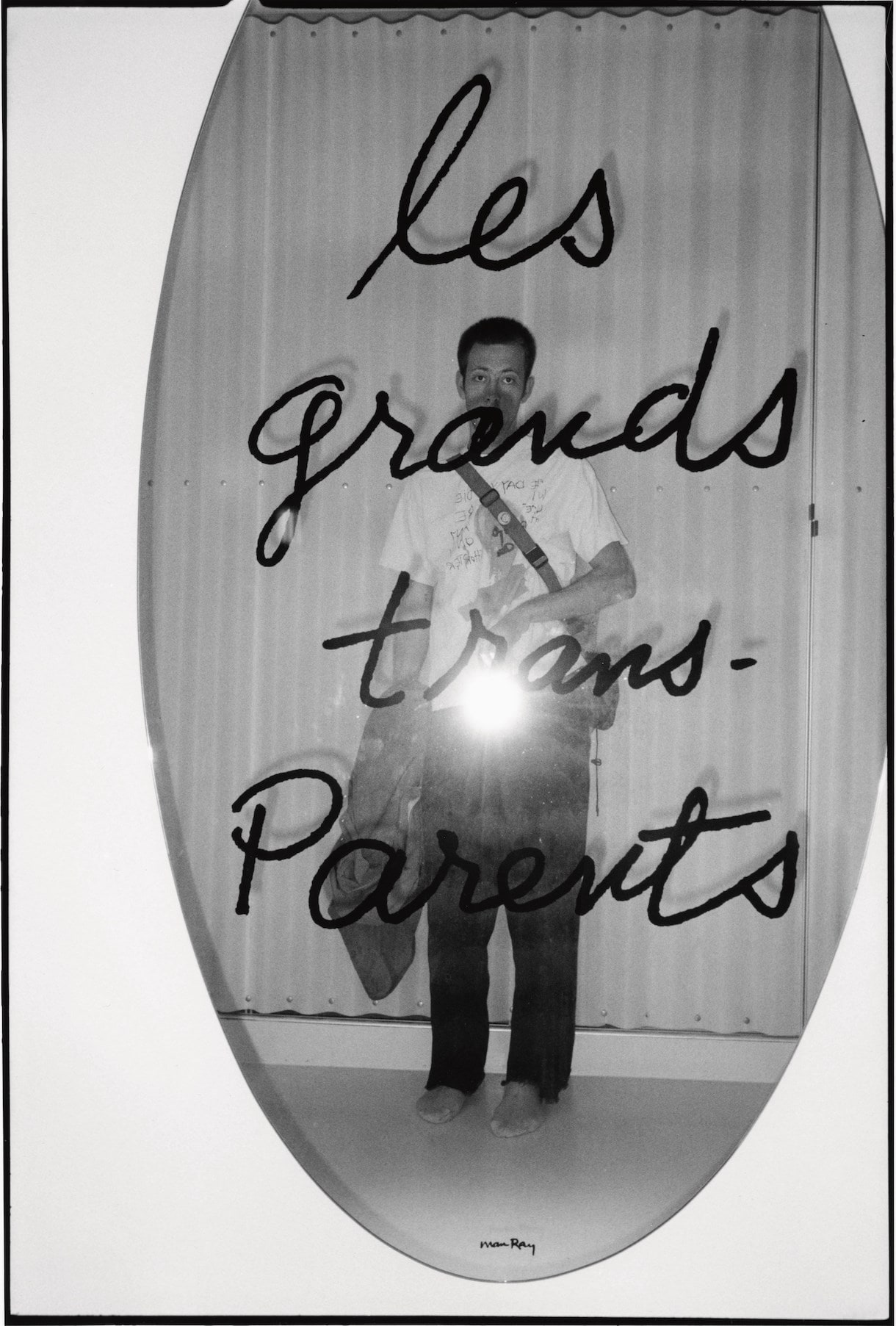

JJ: I used to do one thing at a time, but in the last few years, I do a lot of stuff. I published a book of my newsprint collages, had shows in LA and New York. I curated Paris Photo last year. I have musical projects – did live scores to Man Ray films, a little European tour with Jozef van Wissem. I have my band, SQÜRL. I did a remix of a Rimbaud thing for Patti Smith, a record with Lee Ranaldo, and we’re going to do another improvised record in early January.

HL: What are the different satisfactions of making music as opposed to films?

JJ: Music is very immediate and it’s a conversation. I’m not the captain of the ship as I am with film. Once I was working on a script for months, and I was with Tom Waits and he sits down at a piano, plays a beautiful little song, sings for me, and then it just floats off into the air. It’s a magical, ephemeral thing. And here I’m working on this fucking thing endlessly. I once introduced Tom and Neil Young, had dinner with the two of them and listened to them talk about where their ideas come from. Neil’s metaphor was fishing and Tom’s was waiting to catch a rabbit coming out of a hole.

HL: You’ve spoken about the liberating idea in late seventies New York that people didn’t need to be virtuosos of their craft. This is your 14th film, how has that feeling changed with all the experience you now have?

JJ: I still don’t know what I’m doing. I’m learning each time. Making Father, Mother, I learned a few things about the intimacy of the camera that will inform my next film. I’m a student, always, of everything. I’m a dilettante because I’m interested in too many things, there are no boundaries to it.

HL: What’s something that you are currently obsessed with?

JJ: The theory of a single consciousness in the universe. I’ve been reading Jung and Schrödinger and Terence McKenna. Also psilocybin has been very important to me as a kind of medicine that helps you understand this. I’m obsessed. Now when I walk in the woods upstate it’s like the trees are saying to me, “Aha, we know now that you know the secret.” They speak; it’s very weird. I’m an amateur mycologist. Did you know that?

“It’s easier to make zombies come out of their graves than to be watching Cate Blanchett’s eyelid flicker” – Jim Jarmsuch

HL: I read that you were poisoned by a mushroom.

JJ: Yes, 12 or 15 years ago. I was in a restaurant in downtown New York, and I had wild mushroom pappardelle – it was delicious. Ten o’clock at night I started feeling unwell and by midnight all my internal organs were shutting down. I was rushed to hospital, my stomach was pumped, I lost consciousness. The doctors said an hour later, you’d have gone. They realised the only thing it could have been was a poisonous mushroom, maybe a tiny piece of a death cap. So after that, I became obsessed.

HL: Many people wouldn’t go near them again…

JJ: No, I got drawn to them very strongly. John Cage was a mycologist; he trained Tōru Takemitsu, the Japanese composer. I find them fascinating; they’re far closer in DNA to animals than plants. The mycologist Paul Stamets has this theory: psilocybe used to only grow in meadows and forests but over the last 100 years, they’ve come extremely close to humans. Now they really flourish where there’s been a disaster or humans have changed the landscape. Stamets thinks they’re moving towards us because they’re concerned that we fucked everything up. I mean – we have. He thinks they’re trying to help enlighten us in some way. I think it’s too late, but they’re trying. And I’m trying to listen to them.

Lighting: Alessandro Tranchini. Photographic assistant: Melissa Heane. Styling assistant: Bella Kavanagh. Executive production: DoBeDo Represents. Local production: MAI Productions. Producer: Francesca Miani. Production manager: Alessandro Berreta. Production assistant: Arturo Pagnin. Special thanks to Arielle de Saint Phalle. Jim’s own jewellery (worn throughout)

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from October 30. Pre-order here.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageJim Jarmusch is wearing Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from October 30. Pre-order here.

We meet Jim Jarmusch on Venice’s grand canal, in a 15th-century gothic palazzo – all chandeliers, marble floors and the ghosts of past guests who ranged from Proust to Verdi. It’s the kind of bewitched location the erudite, centuries-old vampires in the filmmaker’s Only Lovers Left Alive might appreciate, with the exception of the Italian sunshine, glinting off green lagoon waters outside. Jarmusch is in the floating city for the premiere of his bittersweet jewel of a film, Father Mother Sister Brother, a beautifully paced, wise, and minutely observed triptych that dwells on the complex interplay between parents and their grown-up children. “It’s anti-action,” says the uncompromising director, with his distinctive, laconic delivery. “It doesn’t have any drama really: no violence, no sex, no nudity, no agenda.” He is three days away from winning the festival’s Golden Lion for it.

Jarmusch is a Johnny Cash kind of dresser, in shades and in black, aside from the tiny gold stickpin mouse on his lapel, and a polkadot patterned notebook in his hands. “I wrote some things in here half asleep…” he explains, “a song called New York Jesus, about Lou Reed.” He writes all his scripts by hand too, in notebooks stashed around his home in the Catskills, and his films feel similarly handmade – closer to paintings, or perhaps the poetry he studied as a student under Kenneth Koch at Columbia. His camera finds the small details and in between moments – the coffee-and-cigarette breaks, taxi rides and throwaway asides that might die on the cutting-room floor in more conventional hands. “Have you seen Buster Keaton’s 1925 film Go West? He sells all his belongings for a train ticket and one sandwich. The whole trip is about the sandwich. How minimal could you get?” he says, delighted. Meanwhile he’ll sometimes skip the drama many directors might consider the point – bypass a prison-escape entirely, say, in swampy 1986 three-hander, Down By Law, which starred longtime comrade Tom Waits.

Almost 40 years after that film, it’s Waits who opens the first chapter of Jarmusch’s latest, as a bohemian father puttering around his weather-beaten New Jersey home on the occasion of a rare visit by his two, much straighter children (Adam Driver and Mayim Bialik). Filled with mordant humour, it sets the course for the film’s meditation on the roles we play among those who share our DNA, the dissonance and fractured communication, the bonds and memories that endure. In Dublin, Charlotte Rampling invites her two daughters (Vicky Krieps and Cate Blanchett) for an awkward annual ritual of tea and cakes, the stilted surface conversation sporadically breaking to reveal glimpses of the inner lives bubbling beneath. Two French-American twins (Luka Sabbat and Indya Moore) grapple with their late parents’ legacy in the final third, a dreamy, beguiling closer set in Paris that envelopes its viewer in the soft melancholy of a Nico song. Between all three, Jarmusch weaves variations and echoes, which extend to his characters’ subtly colourcoordinated clothes, courtesy of Anthony Vaccarello and Saint Laurent, who also co-produced the film.

Since his earliest movies – Permanent Vacation’s tale of a Charlie-Parker-obsessed drifter, shot around a weed-ridden Lower East Side; the grimy, deadpan Stranger Than Paradise, made with leftover film stock gifted by Wim Wenders – Jarmusch has centred the misfits and outsiders, whether bus-driver poets or zombies, conflicted hitmen or Japanese tourists lugging a suitcase around Memphis in search of the spirit of Elvis. The now 72-year-old has remained an inveterate outsider himself, choosing creative control over a studio paycheck and carving his own, idiosyncratic path, an attitude that might have been forged amid the nocturnal life of Downtown New York, where he arrived fresh from America’s industrial heartland – Cuyahoga Falls, a suburb of Akron, Ohio – in the 1970s. The rackety, near bankrupt city he found had blackouts, widespread arson and a prowling serial killer, Son of Sam, but also rock-bottom rents, a pinballing creative scene and a DIY sense of possibility – the Mudd club and CBGBs, where Jarmusch played with his band The Del-Byzanteens, prized expression over technical skill. The director’s love of music continues to run parallel to and inform his filmmaking today, encompassing his current musical outfit, SQÜRL, the documentaries he has made on Crazy Horse and the Stooges, and the singular, spellbinding rhythm of his films.

In his company, it’s easy to see why the cosmopolitan circle of accomplices drawn into Jarmusch’s orbit tend to return again and again, becoming friends as well as collaborators. He is generous and interested, with a magpie-mind for details esoteric and wide-ranging (his “special thanks” credits are always a rewarding read, spanning Joe Strummer to Mary Shelley). Rather like his films, a conversation with Jarmusch takes mercurial detours into unexpected territory. “Yeah,” he says, “but tangents are what it’s all about, man.”

Hannah Lack: Can you talk about the process of writing Father Mother Sister Brother? Do you gather ideas in notebooks like that one you’re holding?

Jim Jarmusch: Yeah, I gather little details and disparate things until they start to form a picture. One thing I do as an exercise before I begin writing is read some prose by Marguerite Duras. She has a beautiful way of reducing things – “She responded with a negative gesture.” I always use Duras to clear my head, try to get a voice close to her style. With my film Paterson I carried ideas for 20 years. This last one came pretty fast, I wrote it in three weeks. And then it’s connect-the-dots – you know those drawings where you don’t know what it’s going to be quite yet? The script is not literature; it’s a map. To me, shooting a film is gathering the things from which you will make the film in the cutting room. I don’t have storyboards, like Hitchcock, very precise. I follow my intuition. But it’s not totally random. This film has a three-part structure that cannot be separated. I worked very hard to have an accumulation of things emotionally. If you watched one without the others, I would be mortified.

HL: You’ve cast many regular collaborators, including Tom Waits. What are the creative pleasures of working with someone like Tom over such a long stretch now?

JJ: Yes, Cate Blanchett and Adam Driver too – you get a kind of shorthand. Tom’s particular, because we’ve been close friends for many years and have had a lot of very strange experiences together.

HL: Can you tell me one?

JJ: Oh gosh, where would I begin? Well, when we were shooting Down By Law, we borrowed this black Jaguar for a few scenes. And at night Tom would say, “Jim, let’s go in the production office, get the keys to the Jag and drive through New Orleans all night.” Which we did, three nights in a row, just Tom and me. We had one cassette in the car, which was Julie London singing Cry Me a River. The third night I said, “Tom, we only got this one song…” He said, “Jim, what more do we need, man?”

HL: Where did you two first meet?

JJ: 1985, at a party that Jean-Michel Basquiat had at Mr. Chow in New York. I knew Jean-Michel, and Andy Warhol was there. Tom and I ended up going out all night to various venues, to Danceteria… we’ve been friends ever since, done five films together now.

“You cannot bludgeon a film into the preconceived thing. You bring what you gathered and then it tells you what it wants” – Jim Jarmusch

HL: You’ve worked with many musicians on scores – John Lurie, Neil Young, RZA… but this one you wrote yourself.

JJ: Yeah I’ve done it a few times. I make a playlist while I’m writing and it informs the end music. With Ghost Dog, I bought all the DJ vinyl of Wu-Tang, which on the B-side had just the instrumental beats. I did a similar thing for Dead Man, where I took the Neil Young/Crazy Horse wilder stuff and patched it together with instrumental sections from Zuma and On the Beach. Oddly for Father Mother I had no music in my head. The music is very spare. With my film Paterson, making the music with Carter Logan wasn’t hard because it’s a central character and his perception of the world. Father Mother has no central character, no viewpoint. So the music ended up being minimal, little cloud formations here and there. I think the film wanted that. I’ve learned that in the editing room, you must listen to what the film wants to be. You cannot bludgeon it into the preconceived thing. You bring what you gathered and then it tells you what it wants. Like when I write good dialogue, I’m hearing the characters talk. It’s kind of weird. They start talking and I write it down.

HL: Is there a particular place you like to go to create your music or do your writing?

JJ: Yes. I have a place up in the Catskill Mountains. It’s quite secluded, very wooded, no people around. A lot of bears, coywolves, birds and raccoons, and beautiful trees. I converted part of the garage into a little recording studio/art room, kind of a teenager’s dream studio. I have my instruments and amplifiers and microphones, and I write there too. But I write all around my place upstate, outside. I write by hand, never on a keyboard. I’m always moving with my notebooks.

HL: I think people imagine you as a city person…

JJ: Well, I love cities dearly. Most cities I fall in love with. Other people think, “Really? You like Baltimore?” New York is my city since I ran away from home at 17. And Paris is very important in my life. So those two are my real lovers. But my New York lover, she’s kind of pushing me away now. She gave me so much energy but now she’s cashing it in on me. But the history of New York is about change. When people say, “Oh, you should have been there in the eighties”–New York is always in flux and always about hustling and money. It’s just less interesting now because young people can’t afford to live there. Paris I got to on a student exchange year and I did not complete my studies because I discovered the Cinémathéque. That’s where I became obsessed with movies.

HL: Not as a kid in Akron, Ohio?

JJ: No, in Akron I saw monster movies. My mother, before she had children, was a movie reviewer for the Akron Beacon Journal, but she was more into Hollywood movies from the 40s and 50s. In Paris I saw films from all over the world, discovered ones that reflect this quiet style that Father Mother has – Ozu, Bresson, Carl Dreyer.

HL: Who were your mentors during those early years?

JJ: Robert Frank was a friend. And two American directors – Nick Ray, I was his ‘assistant’, in quotes, the last two years of his life. I love his films. Johnny Guitar is such a Brechtian Western. You know Nick studied architecture with Frank Lloyd Wright and he designed the sets for it, but they look like cheesy ski lodges. It’s not supposed to be accurately a Western, they all have 60s haircuts. Sam Fuller (Shock Corridor, White Dog) was also a mentor, I hung out with him in Berlin, Paris, New York, LA and Brazil. And William Burroughs I met on the documentary Howard Brookner made about him, just the two of us were the crew. In New York, Burroughs was living in the ‘bunker’ on the Bowery, but we also went to these ghost towns in Colorado with him, and to London. Burroughs was very influential to me in other ways.

HL: In the collage art what do you do?

JJ: Yes. I used to sit with William sometimes when he worked on his scrapbooks, which was him finding juxtapositions in random things he’d find in the newspaper: “It says here: ‘Murdered man found in Kansas, the victim’s body was stuffed in a burlap bag.’ And here’s an advertisement for burlap, made in Oklahoma…” What a mind, my God. He should have been a secret agent. He could have been in the CIA – instead he was this countercultural subversive. One thing I loved that he said to me once: “Jim, we have no reason to assume these aliens are in any way benevolent.” But my real mentors too, are the New York School poets, because I studied with Kenneth Koch, David Shapiro, and Ron Padgett, who wrote the poems for Paterson. In Father Mother, the poet Anne Waldman is the mother you see in the photograph as Tom Waits’ wife. And Frank O’Hara is important because Frank had a manifesto in 1959 called personism, which basically said, you write the poem or make the painting to one person, to a lover or to a friend. I kind of always do that; I don’t want to proclaim to the world. With Father Mother I’m really not trying to say anything. I’m just trying to observe non-judgmentally the complexities of interrelations, in this case familial ones. But there’s no moral, there’s no lesson to be learned. That’s not my thing.

“I’ve always avoided Hollywood or anyone else telling me how to make my films” – Jim Jarmusch

HL: The variations and echoes between the three chapters feel very intricate. Did you let your actors play around with the language?

JJ: They’re all different. Like, Adam and Mayim are very precise actors. Tom needs a longer leash. The first day of shooting, Tom took me aside and said, “Jim, you hired two professional killers. What do I do?” I said, “Tom, we do our way. We know each other; you trust me?” “Yeah, otherwise I wouldn’t be here.” “So, this is going to be great.” I worked with Robert Mitchum for Dead Man and Mr. Mitchum does not improvise. Michael Wincott in Dead Man, I ended up letting him improvise every line because he’d come up with something better.

HL: In your last film, The Dead Don’t Die, you were dealing with zombies, bad weather… how did this shoot compare?

JJ: With The Dead Don’t Die, the financing was on my back about money all the time. Aesthetically, nobody interferes. I have full artistic control. But I would be getting calls about budget – it was very unpleasant. I didn’t want to make a film for four or five years because I didn’t want to go to hospital for the stress of making a movie. This is what I love doing and I’ve always avoided Hollywood or anyone telling me how to make my films. I have final cut, otherwise I don’t do it; I’m not doing this to make commercial films. So, Father Mother was a kind of study in observational filmmaking. It’s anti-action. It doesn’t have any drama really: no violence, no sex, no nudity, no agenda. It’s very cumulative, very delicate. But it was no easier to make. It’s easier to make zombies come out of their graves than to be watching Cate Blanchett’s eyelid flicker. What’s the quote? It takes a lot of effort to make something look effortless. I’m very meticulous about details but once the film is done and I’ve seen it–not at a festival, but with a real audience who don’t know I’m there – after that I never see it again. My French crew on this was fantastic though, a 65 percent female crew, who worked so hard and had an ashtray glued to the camera cart because they’re French and they need to smoke. I’m getting them all back if I can for the next.

HL: Do you speak French?

JJ: I do. Paris and French culture have always been very important to me.

HL: Do you always have projects ongoing?

JJ: I used to do one thing at a time, but in the last few years, I do a lot of stuff. I published a book of my newsprint collages, had shows in LA and New York. I curated Paris Photo last year. I have musical projects – did live scores to Man Ray films, a little European tour with Jozef van Wissem. I have my band, SQÜRL. I did a remix of a Rimbaud thing for Patti Smith, a record with Lee Ranaldo, and we’re going to do another improvised record in early January.

HL: What are the different satisfactions of making music as opposed to films?

JJ: Music is very immediate and it’s a conversation. I’m not the captain of the ship as I am with film. Once I was working on a script for months, and I was with Tom Waits and he sits down at a piano, plays a beautiful little song, sings for me, and then it just floats off into the air. It’s a magical, ephemeral thing. And here I’m working on this fucking thing endlessly. I once introduced Tom and Neil Young, had dinner with the two of them and listened to them talk about where their ideas come from. Neil’s metaphor was fishing and Tom’s was waiting to catch a rabbit coming out of a hole.

HL: You’ve spoken about the liberating idea in late seventies New York that people didn’t need to be virtuosos of their craft. This is your 14th film, how has that feeling changed with all the experience you now have?

JJ: I still don’t know what I’m doing. I’m learning each time. Making Father, Mother, I learned a few things about the intimacy of the camera that will inform my next film. I’m a student, always, of everything. I’m a dilettante because I’m interested in too many things, there are no boundaries to it.

HL: What’s something that you are currently obsessed with?

JJ: The theory of a single consciousness in the universe. I’ve been reading Jung and Schrödinger and Terence McKenna. Also psilocybin has been very important to me as a kind of medicine that helps you understand this. I’m obsessed. Now when I walk in the woods upstate it’s like the trees are saying to me, “Aha, we know now that you know the secret.” They speak; it’s very weird. I’m an amateur mycologist. Did you know that?

“It’s easier to make zombies come out of their graves than to be watching Cate Blanchett’s eyelid flicker” – Jim Jarmsuch

HL: I read that you were poisoned by a mushroom.

JJ: Yes, 12 or 15 years ago. I was in a restaurant in downtown New York, and I had wild mushroom pappardelle – it was delicious. Ten o’clock at night I started feeling unwell and by midnight all my internal organs were shutting down. I was rushed to hospital, my stomach was pumped, I lost consciousness. The doctors said an hour later, you’d have gone. They realised the only thing it could have been was a poisonous mushroom, maybe a tiny piece of a death cap. So after that, I became obsessed.

HL: Many people wouldn’t go near them again…

JJ: No, I got drawn to them very strongly. John Cage was a mycologist; he trained Tōru Takemitsu, the Japanese composer. I find them fascinating; they’re far closer in DNA to animals than plants. The mycologist Paul Stamets has this theory: psilocybe used to only grow in meadows and forests but over the last 100 years, they’ve come extremely close to humans. Now they really flourish where there’s been a disaster or humans have changed the landscape. Stamets thinks they’re moving towards us because they’re concerned that we fucked everything up. I mean – we have. He thinks they’re trying to help enlighten us in some way. I think it’s too late, but they’re trying. And I’m trying to listen to them.

Lighting: Alessandro Tranchini. Photographic assistant: Melissa Heane. Styling assistant: Bella Kavanagh. Executive production: DoBeDo Represents. Local production: MAI Productions. Producer: Francesca Miani. Production manager: Alessandro Berreta. Production assistant: Arturo Pagnin. Special thanks to Arielle de Saint Phalle. Jim’s own jewellery (worn throughout)

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally from October 30. Pre-order here.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.