Rewrite

Expanding on the theme of AnOther Magazine’s Autumn/Winter 2025 issue, we present ten enduring films on the past

Memory – like cinema, in Andrei Tarkovsky’s conception of the form – can be seen as a kind of “sculpting in time”. In such an understanding of the term, the process of remembering is less like taking books from a neatly ordered library shelf and more like an act of creation in and of itself, a complex pulling of threads to produce an image that is true only insofar as it expresses something deep about its maker’s subconscious. We’ve all felt that question arise as to whether a memory is real or somehow counterfeit, drawn either from stories that we tell or the ones we get from family or friends, books or the screen. Many of the best films about memory acknowledge this ambiguity, the absoluteness of the image and its paradoxical unreliability, to convey something of its magic.

To mark a new issue of AnOther devoted to the theme, here are ten films about memory not easily forgotten.

Child slavery, suicide, elder abuse: Kenji Mizoguchi’s period epic of an aristocratic family brought low is dark in ways modern-day edgelords can only dream of. The story turns on the separation of a young governor’s wife from her children, Zushiō and Anju, who are sold as slaves to a local jitō (steward), Sansho. The kids were raised to be good by their kind-hearted father, who was forced into exile when they were young, but soon the years pass and Zushiō learns the cruel indifference of his masters. When a young woman arrives at the camp from the island where her mother was taken, Anju is able to glean from a song that she may still be alive. The song becomes a refrain calling Zushiō back to his humanity, even as it leads Anju down a darker path.

“Nothing distinguishes memories from ordinary moments,” says the narrator in La Jetée, a seminal science-fiction short that’s inspired countless imitators from The Terminator to Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys. “It is only later that they claim remembrance, when they show their scars.” Chris Marker’s film tells the story of a nuclear fallout survivor, ‘the man’ (Davos Hanich), forced into a dangerous time-travel experiment to ensure the survival of the human race. Told through third-person voiceover and a poetic montage of black-and-white stills, it’s a peerless work of imagination whose full meaning, like the memory afflicting its protagonist, only becomes clear when it’s too late.

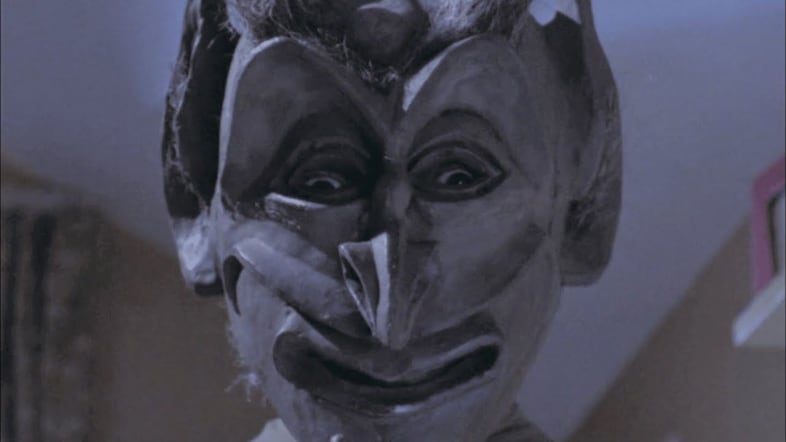

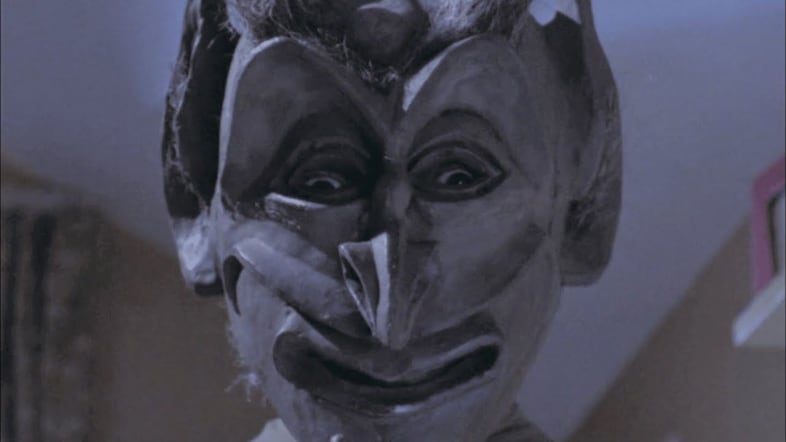

A work of visionary power that almost seems to defy description – its own director, Alan Clarke, claimed not to know what it was about – Penda’s Fen was originally broadcast on BBC1 as part of the Play for Today series, which showcased the work of countless great British dramatists. At heart, it’s the story of a young vicar’s son coming into his sexuality around the same time he starts to question his ultra-conservative Christian values. But that doesn’t begin to explain the weird mystical overtones of writer David Rudkin’s screenplay, which pits competing versions of England’s green and pleasant land against each other in a story taking in William Blake, Edward Elgar, old pagan kings and a whole host of angel and demon figures. Imagine The Wicker Man crossed with Lindsay Anderson’s If …, and you get something of the revolutionary flavour of this film, without doubt one of the weirdest and best things to air on British telly.

Memory was one of Andrei Tarkovsky’s great themes as a director, and Mirror is perhaps his defining word on the subject, plumbing its mysteries through masterful cinematic technique. Notionally telling the story of a dying poet as he recollects scenes from his life, the real star here is a series of haunting and enigmatic images as indelible as anything put on screen, paired with a deeply disorienting, non-narrative structure that casts memory as a phenomenon outside of time.

It’s no coincidence many of the films on this list draw on their authors’ pasts, perhaps none more deeply than Louis Malle’s shattering account of a childhood friendship cut short in Nazi-occupied France. Julien is a factory owner’s kid at a boarding school who grows close to Jean, a new arrival hiding a secret. Unsparing in its judgments on French society under Nazi rule, the whole thing builds to a look between the boys – the hapless wave is particularly soul crushing – and a closing line, “I’ll remember every second of that January morning till the day that I die”, that ranks among the most devastating in all of cinema.

The terraced streets of Liverpool become a tableau vivant in Terence Davies’ sublime autobiographical drama, centred on a working class Catholic family terrorised by its patriarch in the years either side of the Second World War. Drawing heavily on a songbook of music hall, jazz and Hollywood musical numbers to instil a mood of heavy nostalgia, the film wards off sentimentality through its seamlessly edited, time hopping structure and ghostly camerawork comprised of long, processional tracking shots and friezes with the actors looking just off camera. The effect is something like a seance, peering into the lighted windows of a past that remains forever out of reach.

A man is plagued by a series of surveillance videotapes sent anonymously to his home in Michael Haneke’s typically chilly study of repressed cultural memory. The question of who sent them is left deliberately hanging in the air, the better to express its themes of unresolved guilt, but gradually we are led to believe it has something to do with a dark episode in the man’s past. Haneke was inspired by the Paris massacre of Algerians in 1961 for his story; one of the film’s eeriest images comes right at the start, a fixed-camera shot of a bougie Paris neighbourhood suggesting memories that reside not in individual bodies but in actual bricks and mortar, as the untold stories that lie behind Europe’s façade of civilisation.

Read our guide to the films of Michael Haneke here.

“In memories there is no now and then, true or false,” says a character in Long Day’s Journey Into Night, another teasing and elliptical journey through cinematic time from Chinese filmmaker Bi Gan. A disciple of Tarkovsky who shares the master’s love of textured rot and riddling, metaphysical airs, Gan splits his story of a man haunted by the memory of his love into two parts: first, a fragmented account of Luo’s (Huang Jue) affair with gangster’s moll Wan (Tang Wei) and his attempt to track her down years after she vanished. And second, a hallucinatory, hour-long scene filmed as a single, unbroken take – in 3D, no less – that follows Luo down the rabbit hole as he endlessly circles the object of his obsession. It’s a hypnotic, often mystifying watch, Gan’s direction suggesting how our memories can infuse the present and make us replay certain scenes over and over.

A young girl’s holiday with her dad becomes a scene of childhood discovery and trauma in Charlotte Wells’ unforgettable debut, which helped bring Paul Mescal to acclaim as a young dad struggling with the weight of his depression. Loosely autobiographical in nature – Wells’ own father died when she was a teenager – the film frames Mescal’s character, Calum, in ways both mysterious and monumental, honouring the child’s-eye view of a parent whose issues she is only just beginning to understand. It also makes superb use of music as an emotional trigger, from protagonist Sophie’s sad karaoke rendition of Losing My Religion to the climactic scene in which the grown-up Sophie dances with her dad to Queen and David Bowie’s Under Pressure. Looking back on the film three years out from its release, its success seems part of a wider pop-cultural trend towards depicting the 90s as a kind of vanished, pre-digital paradise, just another strand in the film’s prismatic reflection on memory.

Read our interview with Aftersun director Charlotte Wells, here.

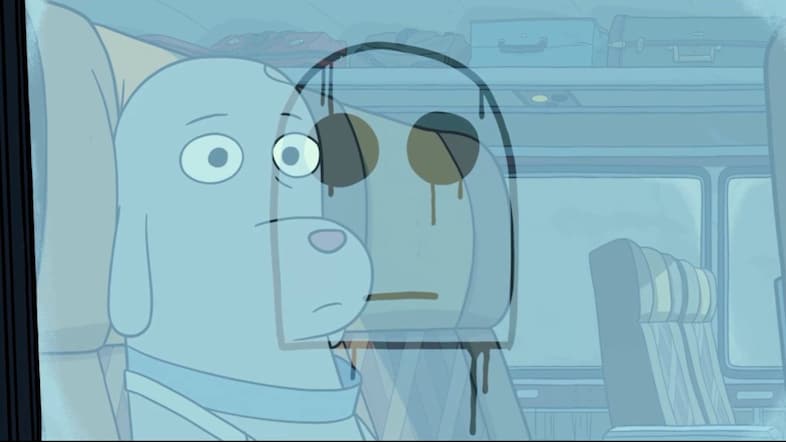

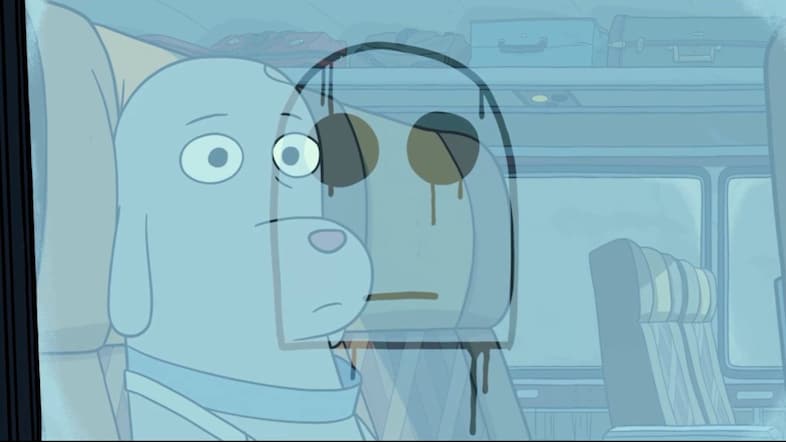

Pablo Berger’s first animated film is a delight from start to finish, but it’s the ending that really makes it sing and secures its spot on this list. When a lonely dog living in 80s New York City orders a robot companion in the post, the pair form a deep but fleeting friendship set to the euphoric strains of Earth, Wind & Fire’s November. Later, when a trip to the beach ends in disaster, they are left to dwell on what might have been – until new friends arrive on the scene to pick up the pieces. The ending brings the reunion we’ve all been hoping for, but Robot makes a decision to leave the past untouched in a way that will honour its memory.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Expanding on the theme of AnOther Magazine’s Autumn/Winter 2025 issue, we present ten enduring films on the past

Memory – like cinema, in Andrei Tarkovsky’s conception of the form – can be seen as a kind of “sculpting in time”. In such an understanding of the term, the process of remembering is less like taking books from a neatly ordered library shelf and more like an act of creation in and of itself, a complex pulling of threads to produce an image that is true only insofar as it expresses something deep about its maker’s subconscious. We’ve all felt that question arise as to whether a memory is real or somehow counterfeit, drawn either from stories that we tell or the ones we get from family or friends, books or the screen. Many of the best films about memory acknowledge this ambiguity, the absoluteness of the image and its paradoxical unreliability, to convey something of its magic.

To mark a new issue of AnOther devoted to the theme, here are ten films about memory not easily forgotten.

Child slavery, suicide, elder abuse: Kenji Mizoguchi’s period epic of an aristocratic family brought low is dark in ways modern-day edgelords can only dream of. The story turns on the separation of a young governor’s wife from her children, Zushiō and Anju, who are sold as slaves to a local jitō (steward), Sansho. The kids were raised to be good by their kind-hearted father, who was forced into exile when they were young, but soon the years pass and Zushiō learns the cruel indifference of his masters. When a young woman arrives at the camp from the island where her mother was taken, Anju is able to glean from a song that she may still be alive. The song becomes a refrain calling Zushiō back to his humanity, even as it leads Anju down a darker path.

“Nothing distinguishes memories from ordinary moments,” says the narrator in La Jetée, a seminal science-fiction short that’s inspired countless imitators from The Terminator to Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys. “It is only later that they claim remembrance, when they show their scars.” Chris Marker’s film tells the story of a nuclear fallout survivor, ‘the man’ (Davos Hanich), forced into a dangerous time-travel experiment to ensure the survival of the human race. Told through third-person voiceover and a poetic montage of black-and-white stills, it’s a peerless work of imagination whose full meaning, like the memory afflicting its protagonist, only becomes clear when it’s too late.

A work of visionary power that almost seems to defy description – its own director, Alan Clarke, claimed not to know what it was about – Penda’s Fen was originally broadcast on BBC1 as part of the Play for Today series, which showcased the work of countless great British dramatists. At heart, it’s the story of a young vicar’s son coming into his sexuality around the same time he starts to question his ultra-conservative Christian values. But that doesn’t begin to explain the weird mystical overtones of writer David Rudkin’s screenplay, which pits competing versions of England’s green and pleasant land against each other in a story taking in William Blake, Edward Elgar, old pagan kings and a whole host of angel and demon figures. Imagine The Wicker Man crossed with Lindsay Anderson’s If …, and you get something of the revolutionary flavour of this film, without doubt one of the weirdest and best things to air on British telly.

Memory was one of Andrei Tarkovsky’s great themes as a director, and Mirror is perhaps his defining word on the subject, plumbing its mysteries through masterful cinematic technique. Notionally telling the story of a dying poet as he recollects scenes from his life, the real star here is a series of haunting and enigmatic images as indelible as anything put on screen, paired with a deeply disorienting, non-narrative structure that casts memory as a phenomenon outside of time.

It’s no coincidence many of the films on this list draw on their authors’ pasts, perhaps none more deeply than Louis Malle’s shattering account of a childhood friendship cut short in Nazi-occupied France. Julien is a factory owner’s kid at a boarding school who grows close to Jean, a new arrival hiding a secret. Unsparing in its judgments on French society under Nazi rule, the whole thing builds to a look between the boys – the hapless wave is particularly soul crushing – and a closing line, “I’ll remember every second of that January morning till the day that I die”, that ranks among the most devastating in all of cinema.

The terraced streets of Liverpool become a tableau vivant in Terence Davies’ sublime autobiographical drama, centred on a working class Catholic family terrorised by its patriarch in the years either side of the Second World War. Drawing heavily on a songbook of music hall, jazz and Hollywood musical numbers to instil a mood of heavy nostalgia, the film wards off sentimentality through its seamlessly edited, time hopping structure and ghostly camerawork comprised of long, processional tracking shots and friezes with the actors looking just off camera. The effect is something like a seance, peering into the lighted windows of a past that remains forever out of reach.

A man is plagued by a series of surveillance videotapes sent anonymously to his home in Michael Haneke’s typically chilly study of repressed cultural memory. The question of who sent them is left deliberately hanging in the air, the better to express its themes of unresolved guilt, but gradually we are led to believe it has something to do with a dark episode in the man’s past. Haneke was inspired by the Paris massacre of Algerians in 1961 for his story; one of the film’s eeriest images comes right at the start, a fixed-camera shot of a bougie Paris neighbourhood suggesting memories that reside not in individual bodies but in actual bricks and mortar, as the untold stories that lie behind Europe’s façade of civilisation.

Read our guide to the films of Michael Haneke here.

“In memories there is no now and then, true or false,” says a character in Long Day’s Journey Into Night, another teasing and elliptical journey through cinematic time from Chinese filmmaker Bi Gan. A disciple of Tarkovsky who shares the master’s love of textured rot and riddling, metaphysical airs, Gan splits his story of a man haunted by the memory of his love into two parts: first, a fragmented account of Luo’s (Huang Jue) affair with gangster’s moll Wan (Tang Wei) and his attempt to track her down years after she vanished. And second, a hallucinatory, hour-long scene filmed as a single, unbroken take – in 3D, no less – that follows Luo down the rabbit hole as he endlessly circles the object of his obsession. It’s a hypnotic, often mystifying watch, Gan’s direction suggesting how our memories can infuse the present and make us replay certain scenes over and over.

A young girl’s holiday with her dad becomes a scene of childhood discovery and trauma in Charlotte Wells’ unforgettable debut, which helped bring Paul Mescal to acclaim as a young dad struggling with the weight of his depression. Loosely autobiographical in nature – Wells’ own father died when she was a teenager – the film frames Mescal’s character, Calum, in ways both mysterious and monumental, honouring the child’s-eye view of a parent whose issues she is only just beginning to understand. It also makes superb use of music as an emotional trigger, from protagonist Sophie’s sad karaoke rendition of Losing My Religion to the climactic scene in which the grown-up Sophie dances with her dad to Queen and David Bowie’s Under Pressure. Looking back on the film three years out from its release, its success seems part of a wider pop-cultural trend towards depicting the 90s as a kind of vanished, pre-digital paradise, just another strand in the film’s prismatic reflection on memory.

Read our interview with Aftersun director Charlotte Wells, here.

Pablo Berger’s first animated film is a delight from start to finish, but it’s the ending that really makes it sing and secures its spot on this list. When a lonely dog living in 80s New York City orders a robot companion in the post, the pair form a deep but fleeting friendship set to the euphoric strains of Earth, Wind & Fire’s November. Later, when a trip to the beach ends in disaster, they are left to dwell on what might have been – until new friends arrive on the scene to pick up the pieces. The ending brings the reunion we’ve all been hoping for, but Robot makes a decision to leave the past untouched in a way that will honour its memory.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.