Rewrite

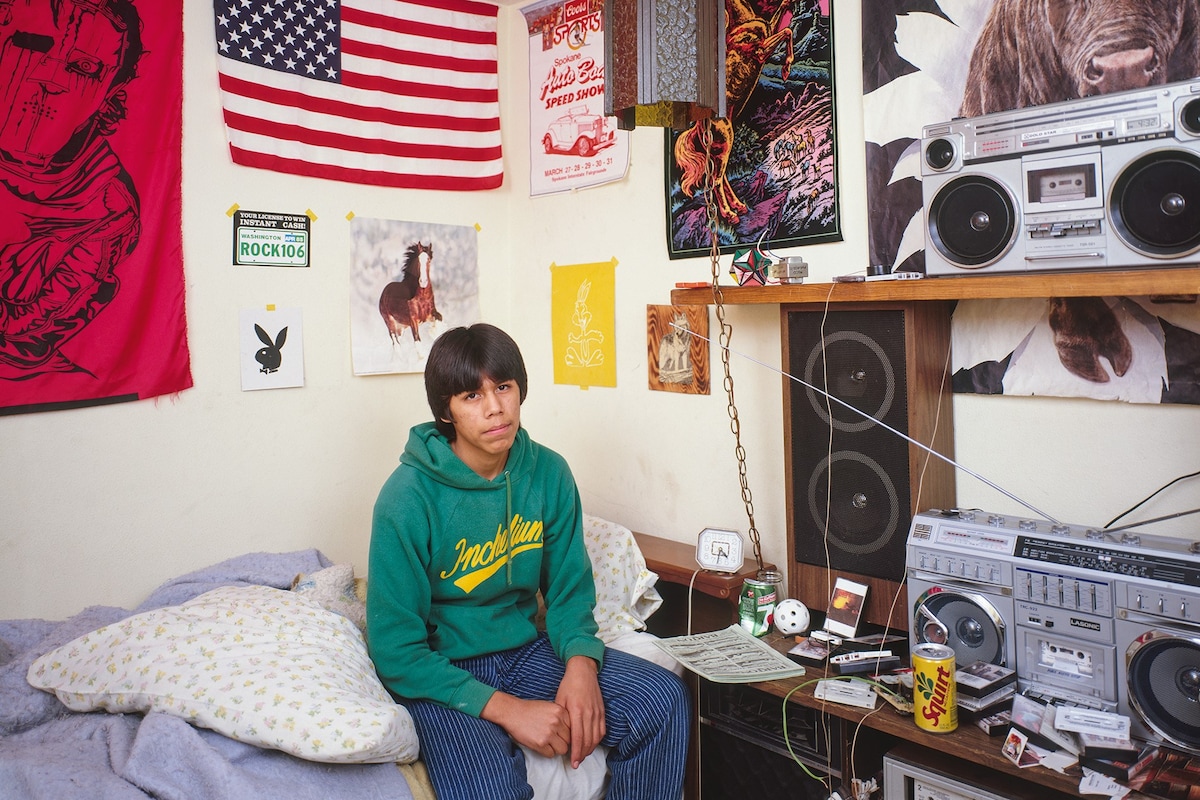

Lead ImageTeenagers in Their BedroomsPhotography by Adrienne Salinger. Courtesy of Artbook

When it comes to photographing the secret lives of teenagers, all roads lead back to Adrienne Salinger. Inspiring countless image-makers and fashion editorials, the Californian photographer’s 1995 book In My Room: Teenagers in Their Bedrooms is a classic so widely referenced and deeply coveted that originals sell on eBay for hundreds of pounds. “When I did the book the first time, my rule was for it to not cost more than a CD,” the artist says over video from her home in New Mexico. “I wanted teenagers to be able to buy it. When I saw how much they were going for these days, I thought it was time to think about a reprint.”

Salinger started the project in the late 1980s, travelling up and down the West Coast to scout for teenagers in malls, in restaurants and on the streets. “I told them not to clean up, not to prepare in any way, and no parents allowed,” she remembers. “It’s surprising to me that so many people say yes.” The project was driven by a frustration with how young people were being portrayed at the time in wider American culture. “The work was really about dismantling stereotypes,” she explains. “At the time that I started it, I just felt strongly that nobody listens to teenagers at all, yet they’re very comfortable commodifying them. I wanted to let teenagers be who they really are.”

Salinger is a warm conversationalist, answering questions with a balance of insightful thought and humour. Yet even with her easy manner, she often found approaching the kids daunting. “It is a little weird to go up to someone, say, in the restroom of a mall and ask, ‘Can I come home with you and photograph you in your bedroom?’ I don’t even know if I could pull that off now,” she says. “But I think that when you do art of any kind, the trick is to always be a little scared.”

Spending entire days in their homes, listening to their stories before photographing them, Salinger captured an authenticity in the teenagers that was unlike anything else seen at the time. Her subjects gaze into her camera – some shyly, others proudly – surrounded by the artefacts of their shifting formative years. First communion mementoes sit beside overflowing ashtrays, pages of Thrasher magazine cover walls behind beds with plush toys on pillowcases, images of heroes like Jim Morrison and Nelson Mandela are taped up in devotional arrangements, while bedside tables brim with trophies, birthday cards and study books. Capturing over 60 young people from all walks of life, each space is a microcosm of expression where versions of the self are tried on and shed, and private explorations edge closer to a world awaiting outside.

The 1995 print was an instant success, but in the years that followed Salinger began to feel she hadn’t told the teenagers’ stories with enough depth. “I felt like I’d failed with the work at that time because I hadn’t quite figured out how to give them enough of a voice,” she says. “I think a lot about representation and about photography, about the trick of it and the vulnerability required to be in photographs. I was conscious to not rip them off, but obviously I’m making the work, so it’s telling a lot about me in this space.”

Later moving to Chicago to study and teach photography, she continued the series prolifically on the East Coast and on Native Indian reserves, this time adding interviews. These later additions and writings are featured in the 2025 reprint. While Salinger is an image-maker, really it’s the stories of the teenagers that kept her coming back to the project. “I think that every single person has an interesting story,” she says. “I know that that’s sort of an obvious thing to say, but it’s true, too. I’m just a person who’s curious about other people‘s experiences.”

“When you do art of any kind, the trick is to always be a little scared” – Adrienne Salinger

Taking stock three decades on from the first portraits, the artist is aware that teenagers today navigate a very different world – one shaped by sociopolitical turbulence and the relentless demands of social media. “When I think about how the world has changed, people no longer assume that they have privacy,” she says. “I stopped teaching just a few years ago, but I found it fascinating to talk to students about privacy. They know that they’re being tracked everywhere they go. They have digital identities that they continually have to update. It’s just very different.”

Asked if teenagers today can still be teenagers, Salinger’s response is both human and academic. “We’re in such a period of change politically and socially, in every possible way,” she says. “I couldn’t possibly know how the current environment affects them. But I do know the idea of a teenager is still a relatively recent phenomenon. Before World War Two, they weren’t really considered their own group. That’s partly because I don’t think the world knew how to market to them. If you look at photographs of interiors of homes from the 1940s and before, teenagers’ rooms didn’t look different from the rest of the house. Advertising to them began at the invention of the nuclear family, in the 60s, which was also when teenagers began rebelling and having autonomy.”

Salinger has created two other bodies of work which both take a similar anthropological angle, People Living Alone and Middle Aged Men, but neither enjoyed the success of her first book. “One of the things about the work that’s kind of always been interesting to me is that I have other books that I’ve done that nobody likes,” says the artist. “The teenagers have never really disappeared for me.”

While her later books are just as visually arresting – in fact, she feels they are technically stronger – the teenagers project has perhaps resonated so widely because we are collectively obsessed with adolescence. The images seem to capture exactly why that is. More than portraits, the messy floors and craftily decorated walls simmer with transformation, rebellion, and possibility, serving as intimate studies of what it means to become oneself.

Released at a moment when young people are entering an uncertain and shifting world, the artist is curious to see how the new book might resonate today. “Often teenagers reach out saying, ‘I saw this in the library,’ or, ‘Here’s my bedroom’. Of course, I love that. I don’t know [how the new book will be received]. Some people might be interested for nostalgia purposes. Some people are just curious about others’ private lives. I’ll be curious to see what happens, but after so much work to put it together, I’m mainly relieved that it got done.”

Teenagers in Their Bedrooms by Adrienne Salinger is published by Artbook and is out August 14.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageTeenagers in Their BedroomsPhotography by Adrienne Salinger. Courtesy of Artbook

When it comes to photographing the secret lives of teenagers, all roads lead back to Adrienne Salinger. Inspiring countless image-makers and fashion editorials, the Californian photographer’s 1995 book In My Room: Teenagers in Their Bedrooms is a classic so widely referenced and deeply coveted that originals sell on eBay for hundreds of pounds. “When I did the book the first time, my rule was for it to not cost more than a CD,” the artist says over video from her home in New Mexico. “I wanted teenagers to be able to buy it. When I saw how much they were going for these days, I thought it was time to think about a reprint.”

Salinger started the project in the late 1980s, travelling up and down the West Coast to scout for teenagers in malls, in restaurants and on the streets. “I told them not to clean up, not to prepare in any way, and no parents allowed,” she remembers. “It’s surprising to me that so many people say yes.” The project was driven by a frustration with how young people were being portrayed at the time in wider American culture. “The work was really about dismantling stereotypes,” she explains. “At the time that I started it, I just felt strongly that nobody listens to teenagers at all, yet they’re very comfortable commodifying them. I wanted to let teenagers be who they really are.”

Salinger is a warm conversationalist, answering questions with a balance of insightful thought and humour. Yet even with her easy manner, she often found approaching the kids daunting. “It is a little weird to go up to someone, say, in the restroom of a mall and ask, ‘Can I come home with you and photograph you in your bedroom?’ I don’t even know if I could pull that off now,” she says. “But I think that when you do art of any kind, the trick is to always be a little scared.”

Spending entire days in their homes, listening to their stories before photographing them, Salinger captured an authenticity in the teenagers that was unlike anything else seen at the time. Her subjects gaze into her camera – some shyly, others proudly – surrounded by the artefacts of their shifting formative years. First communion mementoes sit beside overflowing ashtrays, pages of Thrasher magazine cover walls behind beds with plush toys on pillowcases, images of heroes like Jim Morrison and Nelson Mandela are taped up in devotional arrangements, while bedside tables brim with trophies, birthday cards and study books. Capturing over 60 young people from all walks of life, each space is a microcosm of expression where versions of the self are tried on and shed, and private explorations edge closer to a world awaiting outside.

The 1995 print was an instant success, but in the years that followed Salinger began to feel she hadn’t told the teenagers’ stories with enough depth. “I felt like I’d failed with the work at that time because I hadn’t quite figured out how to give them enough of a voice,” she says. “I think a lot about representation and about photography, about the trick of it and the vulnerability required to be in photographs. I was conscious to not rip them off, but obviously I’m making the work, so it’s telling a lot about me in this space.”

Later moving to Chicago to study and teach photography, she continued the series prolifically on the East Coast and on Native Indian reserves, this time adding interviews. These later additions and writings are featured in the 2025 reprint. While Salinger is an image-maker, really it’s the stories of the teenagers that kept her coming back to the project. “I think that every single person has an interesting story,” she says. “I know that that’s sort of an obvious thing to say, but it’s true, too. I’m just a person who’s curious about other people‘s experiences.”

“When you do art of any kind, the trick is to always be a little scared” – Adrienne Salinger

Taking stock three decades on from the first portraits, the artist is aware that teenagers today navigate a very different world – one shaped by sociopolitical turbulence and the relentless demands of social media. “When I think about how the world has changed, people no longer assume that they have privacy,” she says. “I stopped teaching just a few years ago, but I found it fascinating to talk to students about privacy. They know that they’re being tracked everywhere they go. They have digital identities that they continually have to update. It’s just very different.”

Asked if teenagers today can still be teenagers, Salinger’s response is both human and academic. “We’re in such a period of change politically and socially, in every possible way,” she says. “I couldn’t possibly know how the current environment affects them. But I do know the idea of a teenager is still a relatively recent phenomenon. Before World War Two, they weren’t really considered their own group. That’s partly because I don’t think the world knew how to market to them. If you look at photographs of interiors of homes from the 1940s and before, teenagers’ rooms didn’t look different from the rest of the house. Advertising to them began at the invention of the nuclear family, in the 60s, which was also when teenagers began rebelling and having autonomy.”

Salinger has created two other bodies of work which both take a similar anthropological angle, People Living Alone and Middle Aged Men, but neither enjoyed the success of her first book. “One of the things about the work that’s kind of always been interesting to me is that I have other books that I’ve done that nobody likes,” says the artist. “The teenagers have never really disappeared for me.”

While her later books are just as visually arresting – in fact, she feels they are technically stronger – the teenagers project has perhaps resonated so widely because we are collectively obsessed with adolescence. The images seem to capture exactly why that is. More than portraits, the messy floors and craftily decorated walls simmer with transformation, rebellion, and possibility, serving as intimate studies of what it means to become oneself.

Released at a moment when young people are entering an uncertain and shifting world, the artist is curious to see how the new book might resonate today. “Often teenagers reach out saying, ‘I saw this in the library,’ or, ‘Here’s my bedroom’. Of course, I love that. I don’t know [how the new book will be received]. Some people might be interested for nostalgia purposes. Some people are just curious about others’ private lives. I’ll be curious to see what happens, but after so much work to put it together, I’m mainly relieved that it got done.”

Teenagers in Their Bedrooms by Adrienne Salinger is published by Artbook and is out August 14.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.