Rewrite

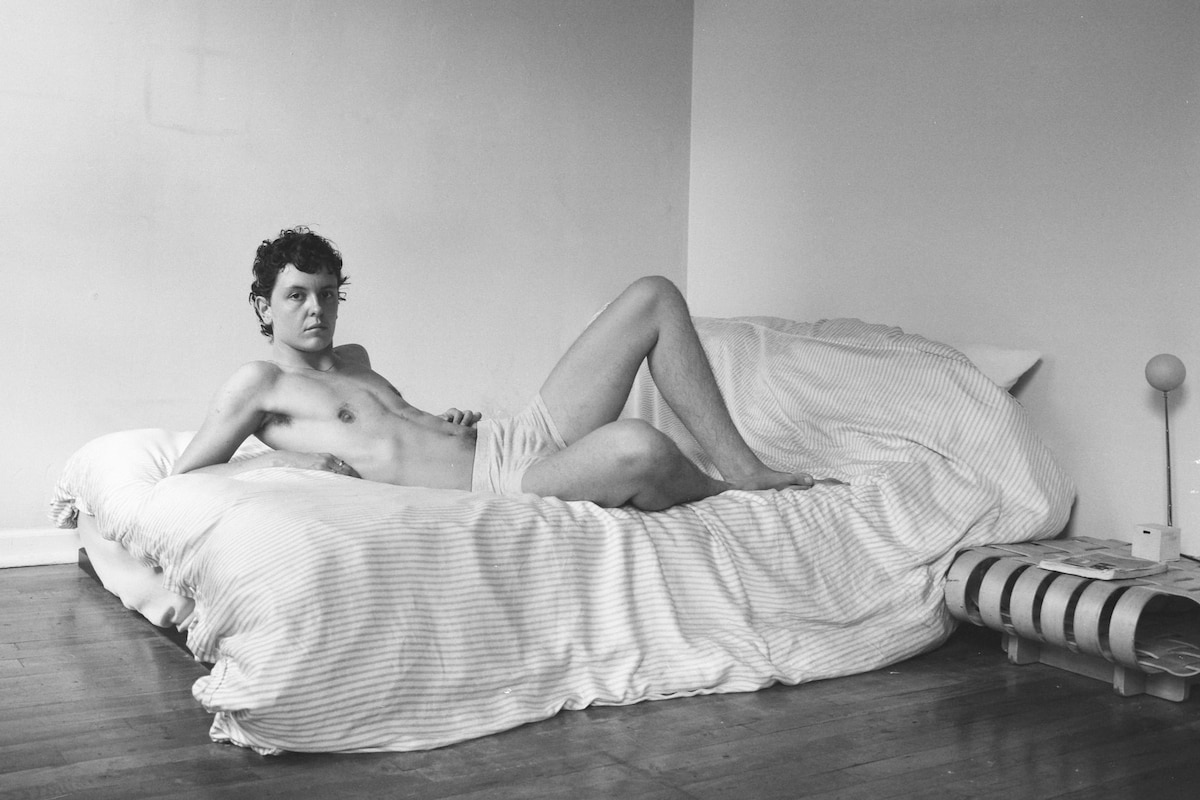

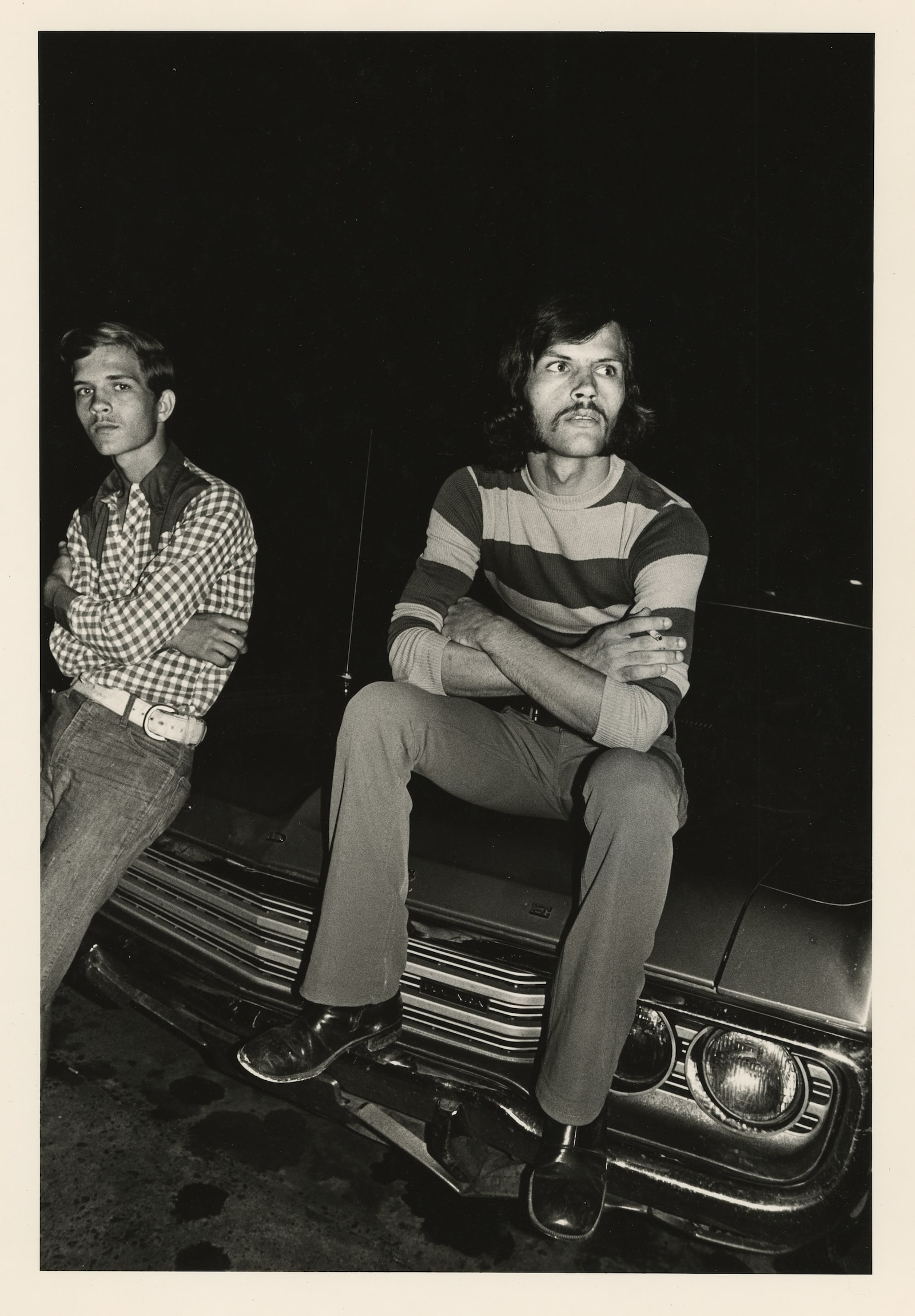

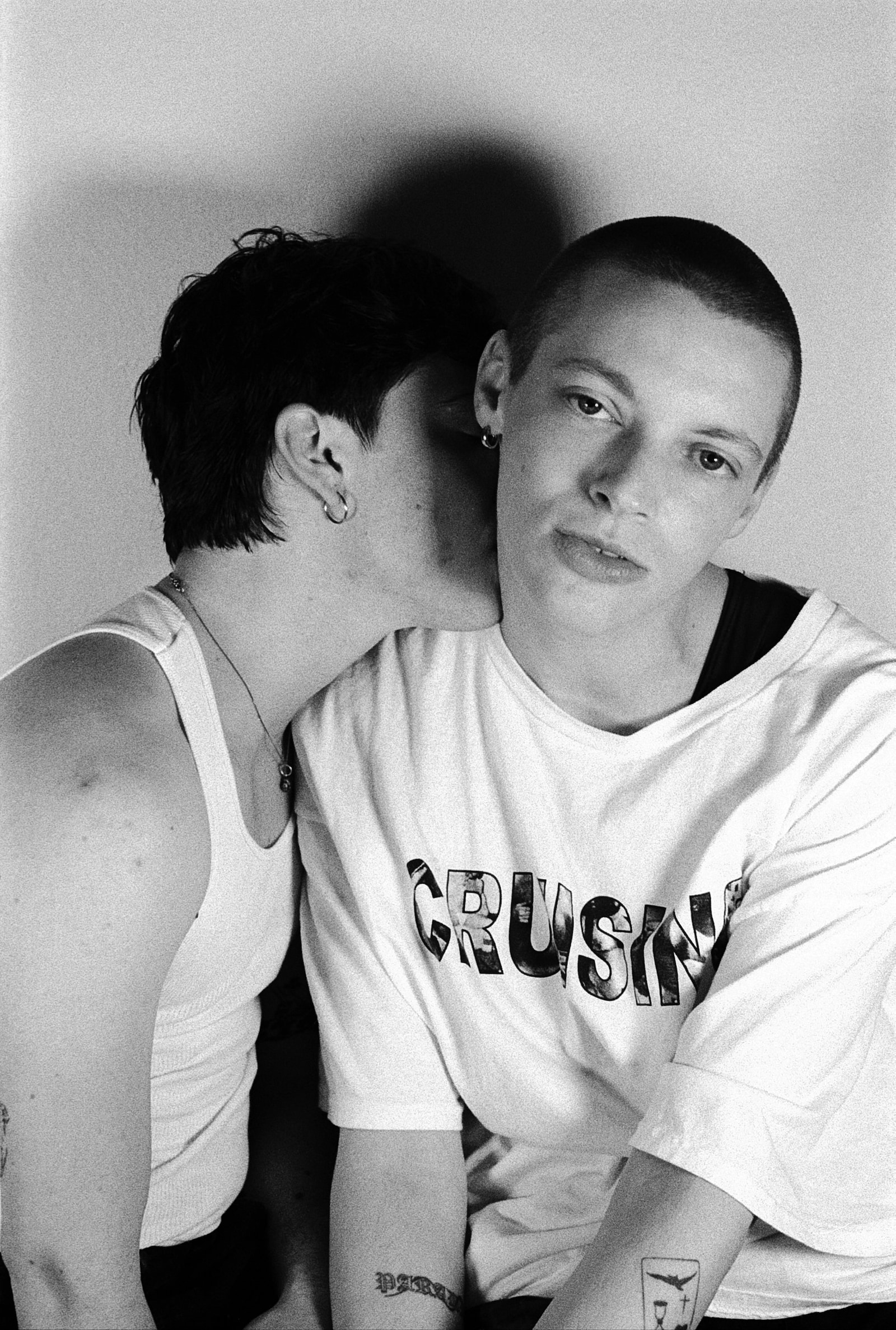

Lead ImagePaul Burnham Schwartz, MateusPhotography by Paul Burnham Schwartz

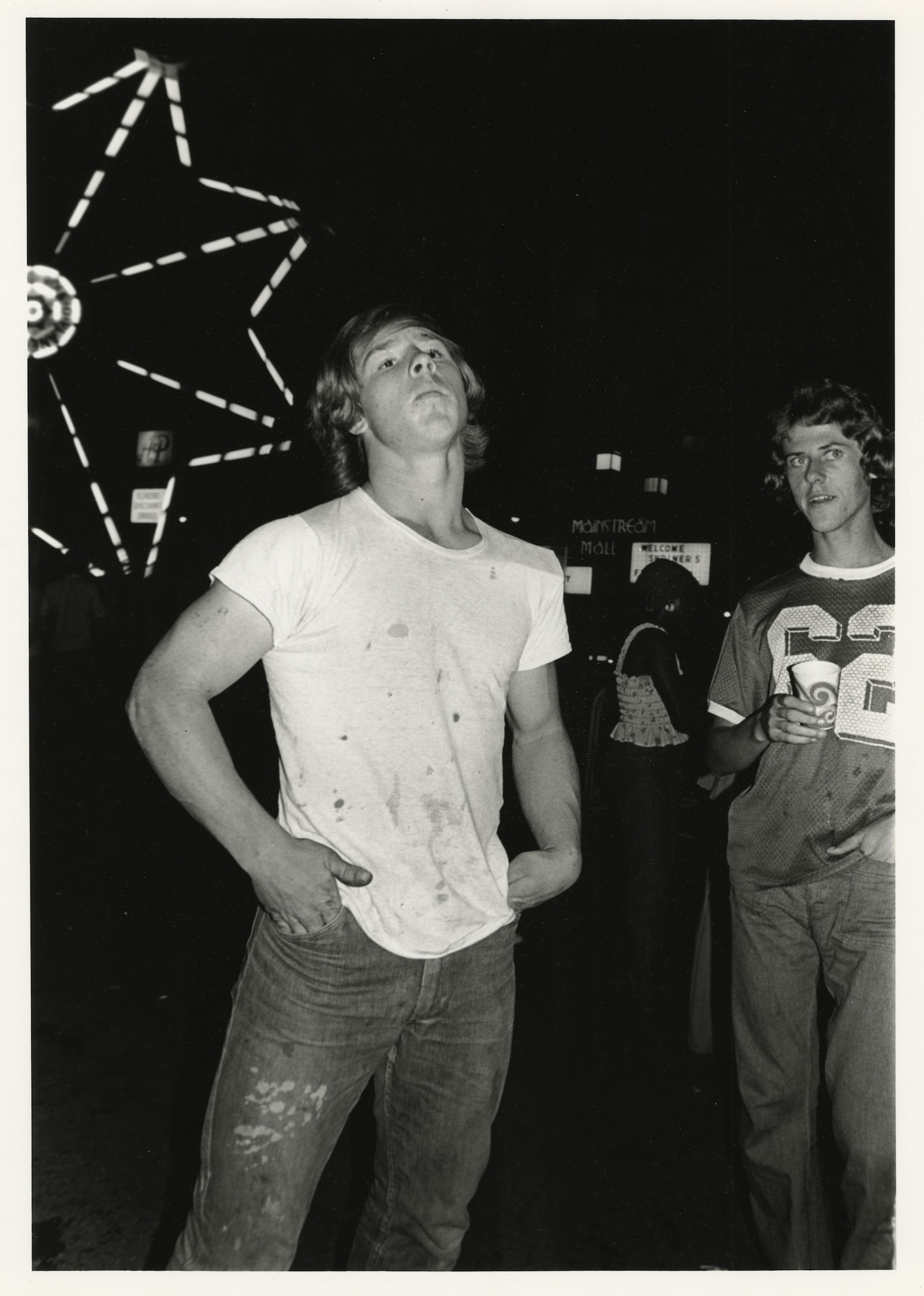

Contemporary queer art often feels like it’s grappling with the past; as if it’s still trying to find a way out from the shadow of the Aids crisis. The photographer Paul Burnham Schwartz grapples with not just the loss brought about by the Aids epidemic, but by the art and artists that documented it. By continuing the lineage of gay male portraiture from the 20th century, seen in the work of artists like Peter Hujar and Allen Frame – often monochromatic, stark, intimate images – Schwartz creates a dialogue between queer history, and the possibilities within a queer future, asserting that this history can serve as a lineage of queer manhood for contemporary transgender men. Matte, a contemporary photography magazine edited by Matthew Leifheit, recently published a book of Paul’s photographs, with writing from The New Yorker’s Holden Seidlitz.

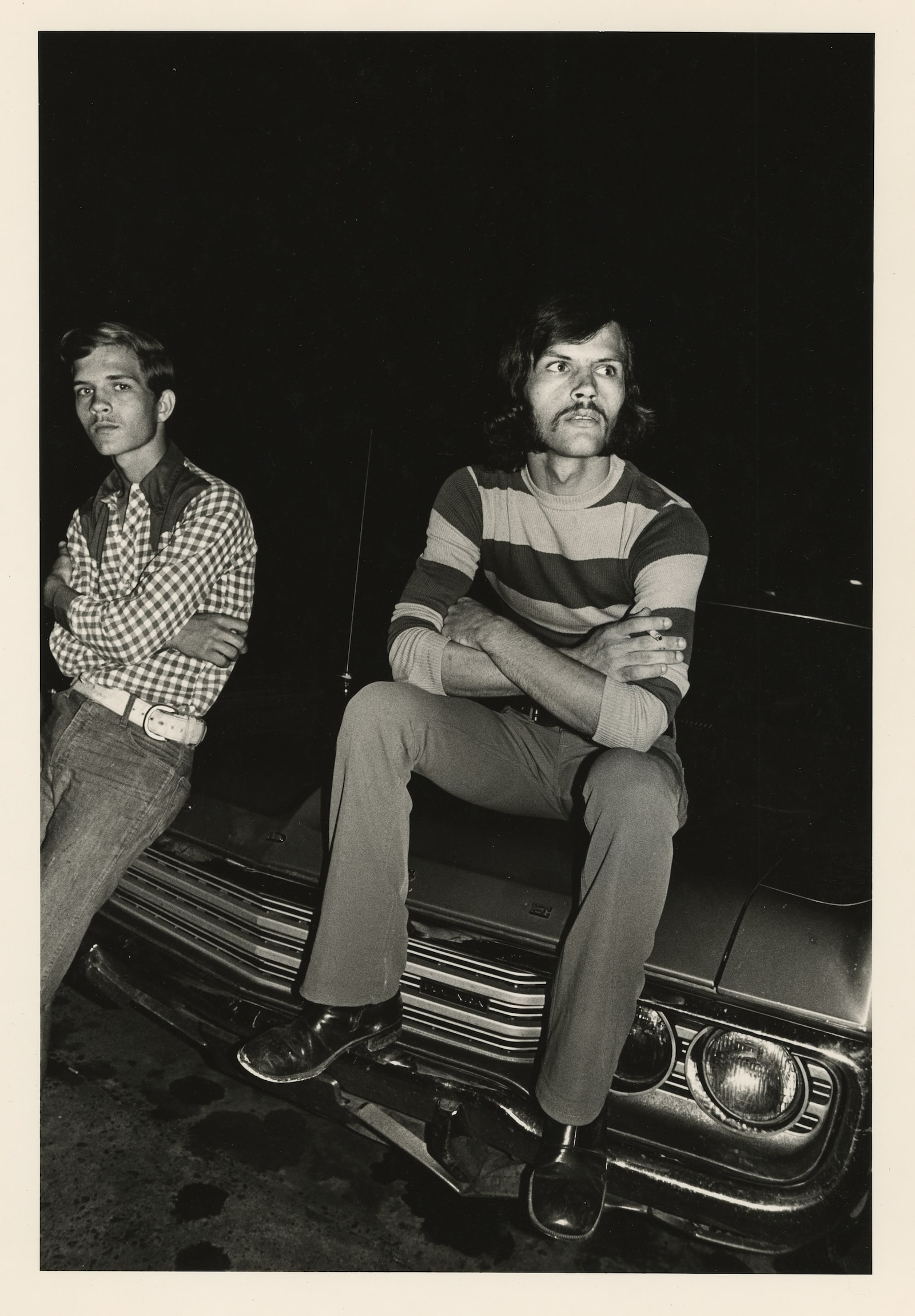

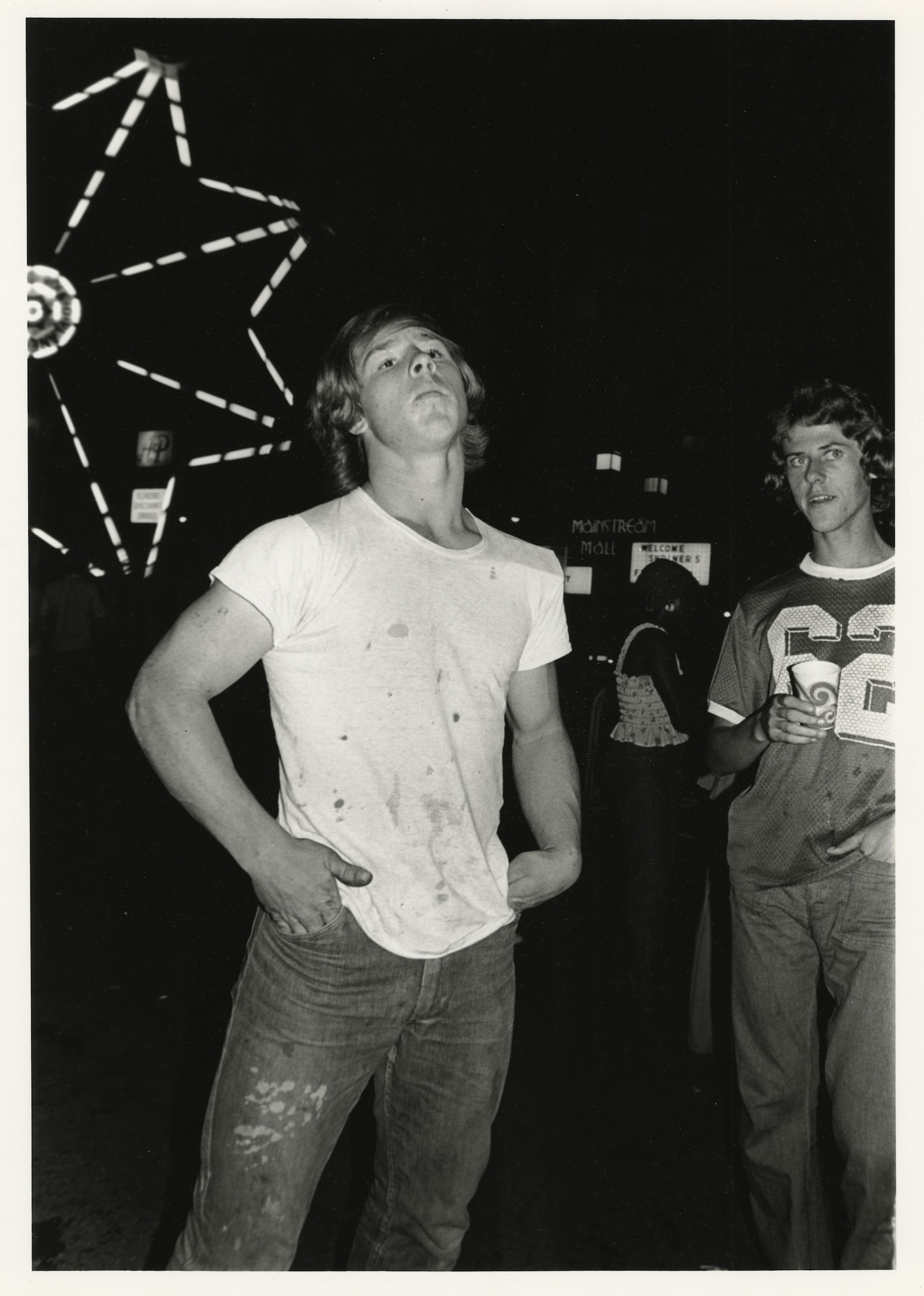

Allen Frame is an early member of the Boston School of photographers; a contemporary of artists like David Armstrong and Nan Goldin. Like Goldin, Frame presents images of friends and acquaintances, captured somewhere between nonchalance and the staged poses of a photography studio. There’s an unguarded intimacy to his work, a sense of being granted the permission to see something private, and to hold onto it like a secret.

Here, the two artists discuss the looming nature of history and influence, why they photograph their friends, and what lies in store for queer art.

Paul Burnham Schwartz: I really came into my practice through New York City history, queer history, Aids history, with the feeling that it’s important to have a theory of history for the place where you live. I’ve only lived in Brooklyn for eight years, so I guess I still can’t even really consider myself a New Yorker.

But before I took photos, I was reading a lot of writing from late 20th century gay male writers, David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives, but also From Welfare State to Real Estate and Gentrification of the Mind by Sarah Schulman. And the first photographers I became interested in were also gay male photographers working at this time, Boston School photographers like you, David Armstrong, Mark Morrisroe, and then, later, Peter Hujar. I started photographing dinner parties I was having at my apartment and later moved into more formal portraiture, which is what’s in the magazine.

Allen Frame: I’m happy that we had the chance to meet through your launch recently. I’ve known Matthew [Leifheit] for a while and I really trust his vision.

PBS: Matt gave me your book around the time we first met, and I saw that in Fever you were making photographs in a similar context to me: in our homes, with our friends, cooking food. What’s compelling to me about the Boston School is seeing them do what has been coined “insider documentary” photography; the idea that working with your friends, the spaces where you exist, could be important work and material for great art.

“My work is art first, not identity first … I want my pictures to be good pictures before anything else” – Paul Burnham Schwartz

AF: I’m more comfortable photographing friends and family than strangers. If photography had only been about strangers throughout the 20th century, I probably would have gone into another medium. One of the things that made me want to be a photographer was seeing the work of Emmet Gowin. I saw his work on family and neighbours and Diane Arbus’ work in the same show. Then the first teacher I had, Henry Horenstein, was photographing his friends and parents and their friends. So that kind of work legitimised the photography that had been relegated to albums and snapshots.

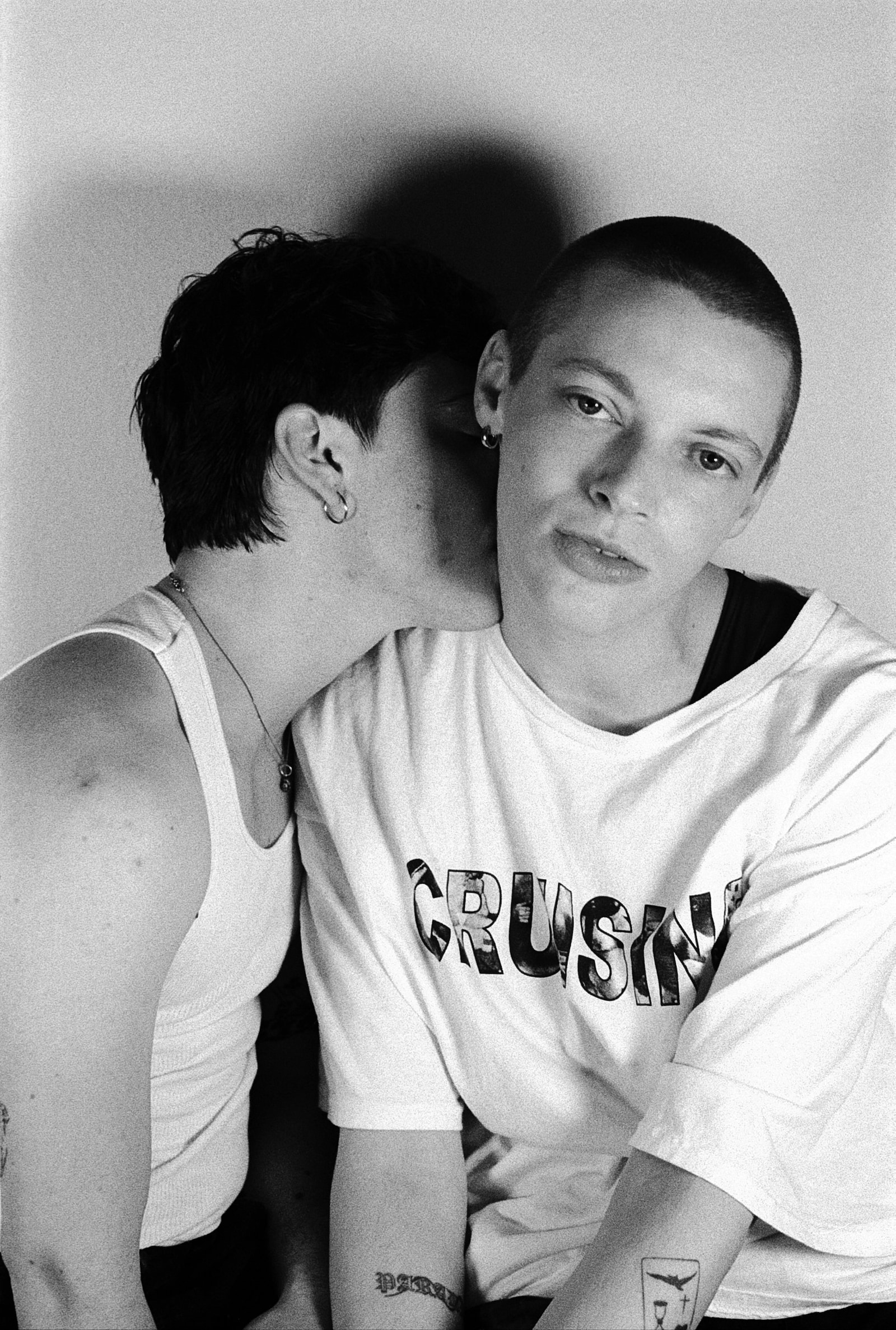

PBS: One of the theses for the work in Matte is that gay male history is a lineage for transgender men and transmasculine people. The trans experience has a particular relationship to lineage in that you adopt it at an older age. Looking through gay male photographic archival materials – porn and physique magazines like Physique Pictorial and Straight to Hell, photo books, etcetera – and making work in their lineage was an identity formation project for me. Queer people long to ground themselves in history in a way that makes the search more desperate, almost like an appeal for our humanity, that people like us have always existed.

AF: In my case, what I was doing with photography was queering the canon that had been created mostly by straight men. In art history, however, the artist I’m still more excited by than anybody is Caravaggio, who was queer. I was grateful to discover any artists that came before me. On another level, mentorship was hugely important to me, gay men of an older generation who told me stories of their experience.

PBS: Ira Sachs has The Last Address Project, a walking tour of the last addresses of artists in New York who died of Aids. Living in New York is living among ghosts. There’s an absence of intergenerational relationships, and art, and all sorts of things that will never come to pass.

“As a reaction to Aids trauma, there was very little work about sexuality after the early 90s … people just didn’t have the capacity to think about that” – Allen Frame

AF: I also find it a haunted cityscape. My salvation has been being able to live in different neighbourhoods, moving from the East Village to Williamsburg. I’m in Sunnyside, Queens now, where I don’t know anybody. I’m happy because it’s such a fresh space. Of course, I had many losses. When I think of the 80s, I think of how brutal it all was. I could inventory wonderful, pivotal, great experiences, but it’s all very much overshadowed by the devastation of the Aids pandemic.

PBS: I think part of having a theory of history is knowing that nothing is ever truly novel. Of course, it’s ever been this way before now, but what’s so comforting is people have felt the way we feel, and they’ve lived through it.

AF: As a reaction to Aids trauma, there was very little work about sexuality after the early 90s. There was a lot of work about identity, but there was a tapering off of work about sexuality. People just didn’t have the capacity to think about that.

But when Ryan McGinley came on the scene in 2002, a lot of his work was about his friends in Williamsburg, and some of that was very much about sexuality. And it was kind of a shock because it hadn’t been seen in a long time. And then the floodgates were open and more people were able to deal with that and express it.

PBS: Another value I hold in my work is that it’s art first, not identity first. There’s this phenomenon that we’ve all witnessed where work is pigeonholed as “trans art” or “queer art” and put beyond proper critique because people fear cancellation if they say anything. That’s such a disservice to queer and trans artists, but also to the public. I want my pictures to be good pictures before anything else.

Matte Magazine Issue 65: Paul Burnham Schwartz is out now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImagePaul Burnham Schwartz, MateusPhotography by Paul Burnham Schwartz

Contemporary queer art often feels like it’s grappling with the past; as if it’s still trying to find a way out from the shadow of the Aids crisis. The photographer Paul Burnham Schwartz grapples with not just the loss brought about by the Aids epidemic, but by the art and artists that documented it. By continuing the lineage of gay male portraiture from the 20th century, seen in the work of artists like Peter Hujar and Allen Frame – often monochromatic, stark, intimate images – Schwartz creates a dialogue between queer history, and the possibilities within a queer future, asserting that this history can serve as a lineage of queer manhood for contemporary transgender men. Matte, a contemporary photography magazine edited by Matthew Leifheit, recently published a book of Paul’s photographs, with writing from The New Yorker’s Holden Seidlitz.

Allen Frame is an early member of the Boston School of photographers; a contemporary of artists like David Armstrong and Nan Goldin. Like Goldin, Frame presents images of friends and acquaintances, captured somewhere between nonchalance and the staged poses of a photography studio. There’s an unguarded intimacy to his work, a sense of being granted the permission to see something private, and to hold onto it like a secret.

Here, the two artists discuss the looming nature of history and influence, why they photograph their friends, and what lies in store for queer art.

Paul Burnham Schwartz: I really came into my practice through New York City history, queer history, Aids history, with the feeling that it’s important to have a theory of history for the place where you live. I’ve only lived in Brooklyn for eight years, so I guess I still can’t even really consider myself a New Yorker.

But before I took photos, I was reading a lot of writing from late 20th century gay male writers, David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives, but also From Welfare State to Real Estate and Gentrification of the Mind by Sarah Schulman. And the first photographers I became interested in were also gay male photographers working at this time, Boston School photographers like you, David Armstrong, Mark Morrisroe, and then, later, Peter Hujar. I started photographing dinner parties I was having at my apartment and later moved into more formal portraiture, which is what’s in the magazine.

Allen Frame: I’m happy that we had the chance to meet through your launch recently. I’ve known Matthew [Leifheit] for a while and I really trust his vision.

PBS: Matt gave me your book around the time we first met, and I saw that in Fever you were making photographs in a similar context to me: in our homes, with our friends, cooking food. What’s compelling to me about the Boston School is seeing them do what has been coined “insider documentary” photography; the idea that working with your friends, the spaces where you exist, could be important work and material for great art.

“My work is art first, not identity first … I want my pictures to be good pictures before anything else” – Paul Burnham Schwartz

AF: I’m more comfortable photographing friends and family than strangers. If photography had only been about strangers throughout the 20th century, I probably would have gone into another medium. One of the things that made me want to be a photographer was seeing the work of Emmet Gowin. I saw his work on family and neighbours and Diane Arbus’ work in the same show. Then the first teacher I had, Henry Horenstein, was photographing his friends and parents and their friends. So that kind of work legitimised the photography that had been relegated to albums and snapshots.

PBS: One of the theses for the work in Matte is that gay male history is a lineage for transgender men and transmasculine people. The trans experience has a particular relationship to lineage in that you adopt it at an older age. Looking through gay male photographic archival materials – porn and physique magazines like Physique Pictorial and Straight to Hell, photo books, etcetera – and making work in their lineage was an identity formation project for me. Queer people long to ground themselves in history in a way that makes the search more desperate, almost like an appeal for our humanity, that people like us have always existed.

AF: In my case, what I was doing with photography was queering the canon that had been created mostly by straight men. In art history, however, the artist I’m still more excited by than anybody is Caravaggio, who was queer. I was grateful to discover any artists that came before me. On another level, mentorship was hugely important to me, gay men of an older generation who told me stories of their experience.

PBS: Ira Sachs has The Last Address Project, a walking tour of the last addresses of artists in New York who died of Aids. Living in New York is living among ghosts. There’s an absence of intergenerational relationships, and art, and all sorts of things that will never come to pass.

“As a reaction to Aids trauma, there was very little work about sexuality after the early 90s … people just didn’t have the capacity to think about that” – Allen Frame

AF: I also find it a haunted cityscape. My salvation has been being able to live in different neighbourhoods, moving from the East Village to Williamsburg. I’m in Sunnyside, Queens now, where I don’t know anybody. I’m happy because it’s such a fresh space. Of course, I had many losses. When I think of the 80s, I think of how brutal it all was. I could inventory wonderful, pivotal, great experiences, but it’s all very much overshadowed by the devastation of the Aids pandemic.

PBS: I think part of having a theory of history is knowing that nothing is ever truly novel. Of course, it’s ever been this way before now, but what’s so comforting is people have felt the way we feel, and they’ve lived through it.

AF: As a reaction to Aids trauma, there was very little work about sexuality after the early 90s. There was a lot of work about identity, but there was a tapering off of work about sexuality. People just didn’t have the capacity to think about that.

But when Ryan McGinley came on the scene in 2002, a lot of his work was about his friends in Williamsburg, and some of that was very much about sexuality. And it was kind of a shock because it hadn’t been seen in a long time. And then the floodgates were open and more people were able to deal with that and express it.

PBS: Another value I hold in my work is that it’s art first, not identity first. There’s this phenomenon that we’ve all witnessed where work is pigeonholed as “trans art” or “queer art” and put beyond proper critique because people fear cancellation if they say anything. That’s such a disservice to queer and trans artists, but also to the public. I want my pictures to be good pictures before anything else.

Matte Magazine Issue 65: Paul Burnham Schwartz is out now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.