Rewrite

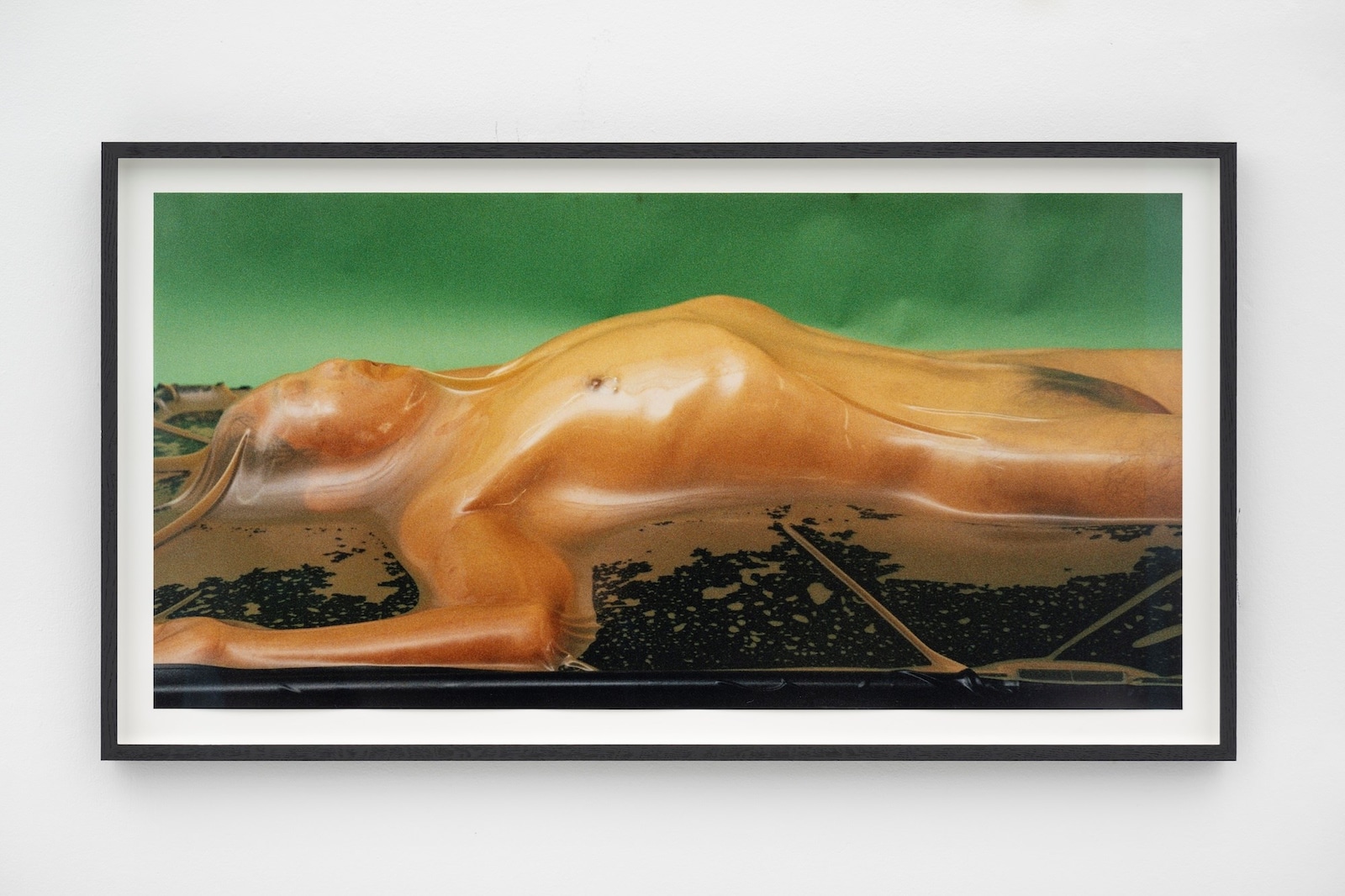

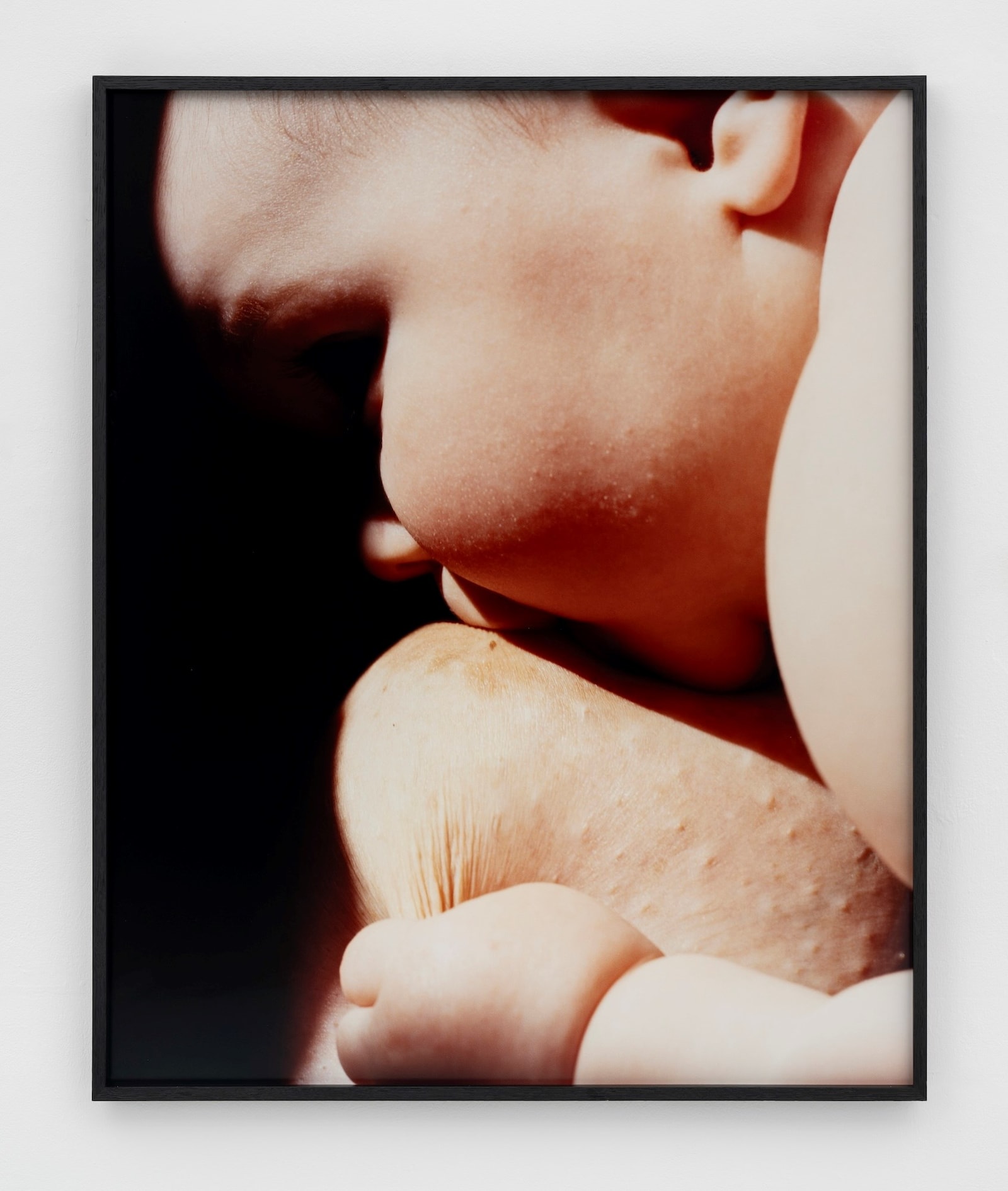

Lead ImageBed, 2007© Harley Weir Courtesy the artist and Hannah Barry Gallery, London, UK

Artists have long fallen under the spell of the garden. From Milton to Monet to Derek Jarman, the subject has inspired masterpieces of Edenic pleasure and stories shaped by the toil of growth. But Harley Weir’s take on the theme is unlike any you would have seen before. Spread across two floors of Hannah Barry Gallery in Peckham, her garden is less a pastoral sanctuary than a psychological arena – here she questions what it means to come of age as a woman.

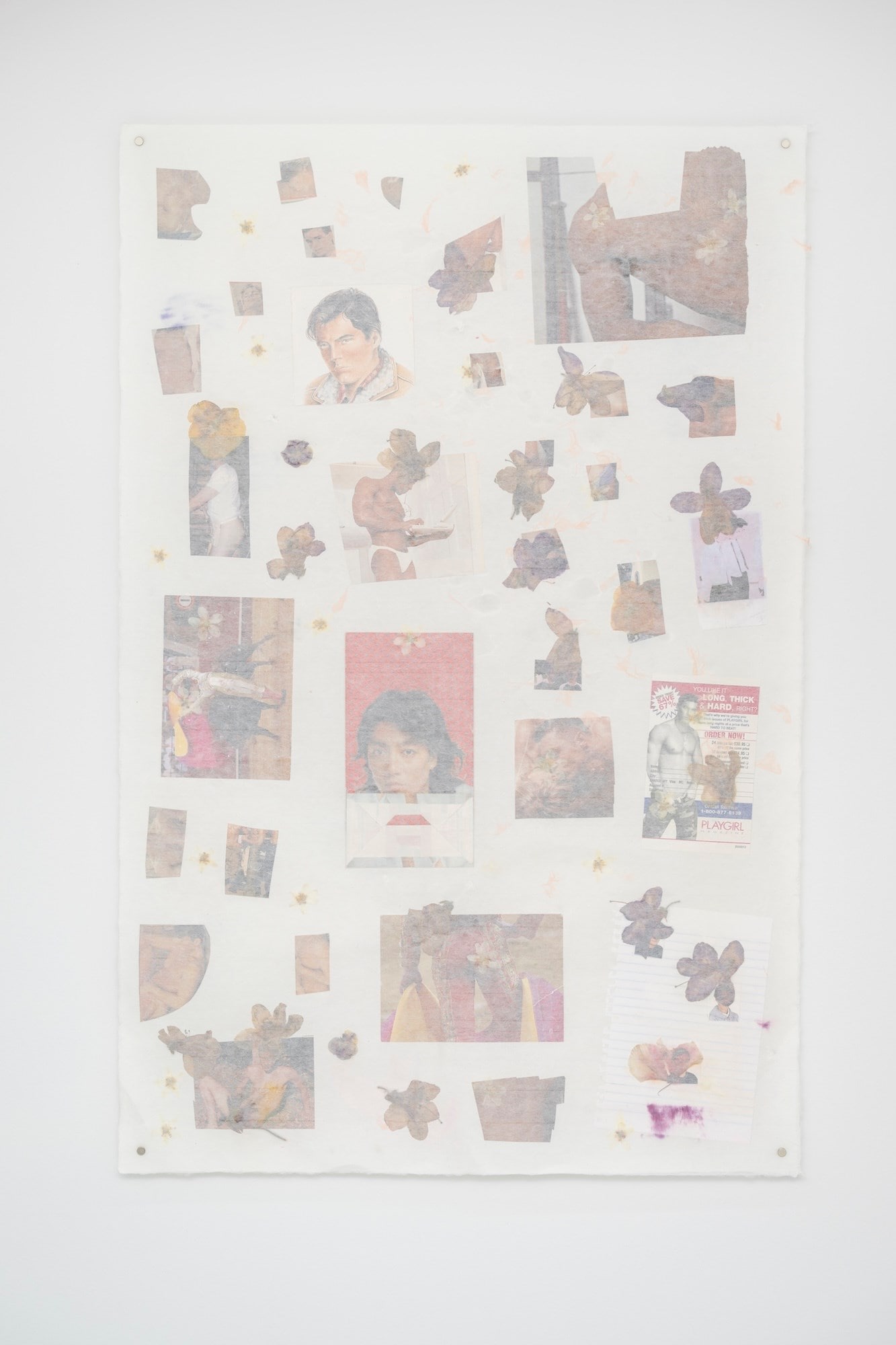

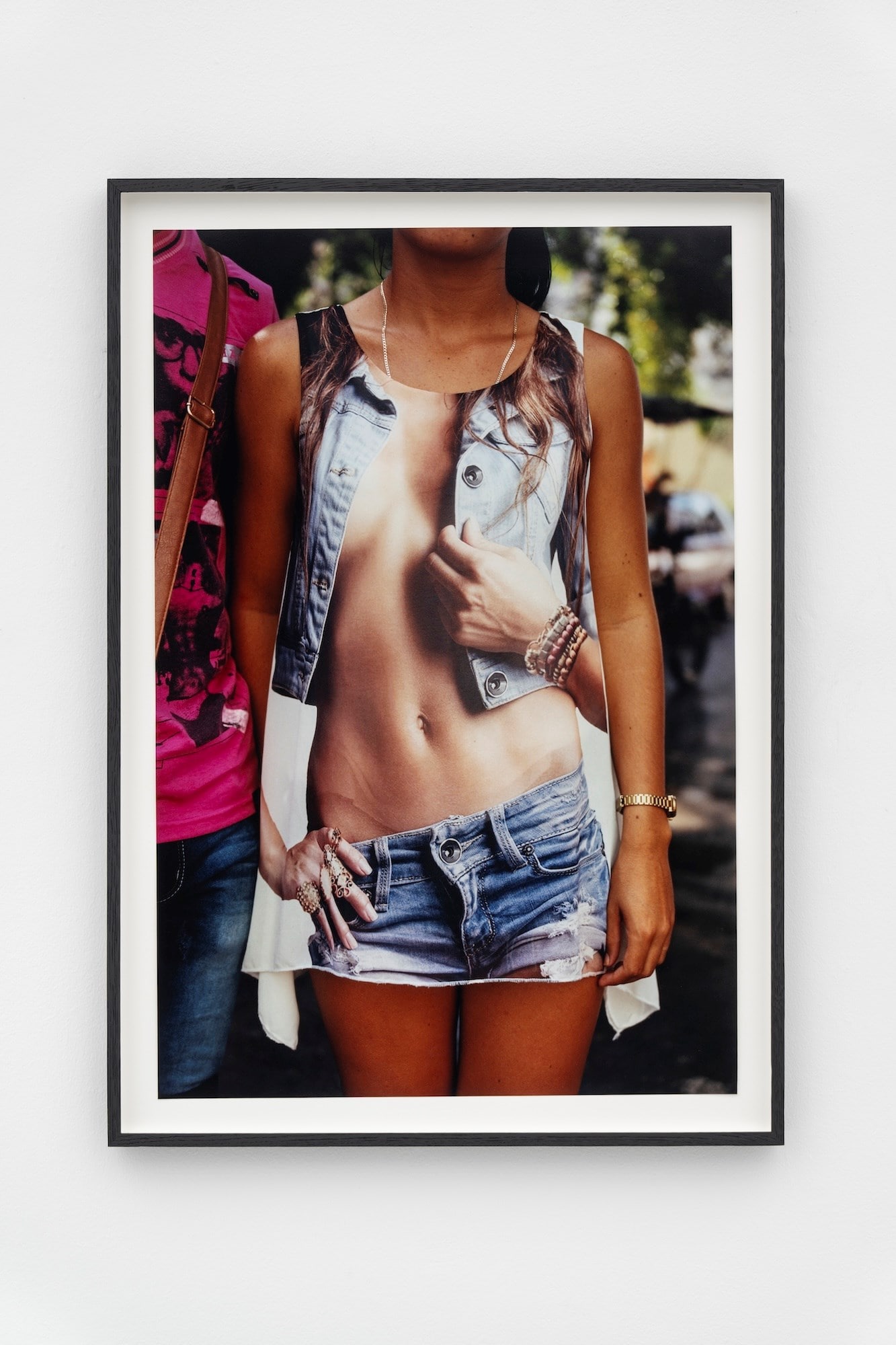

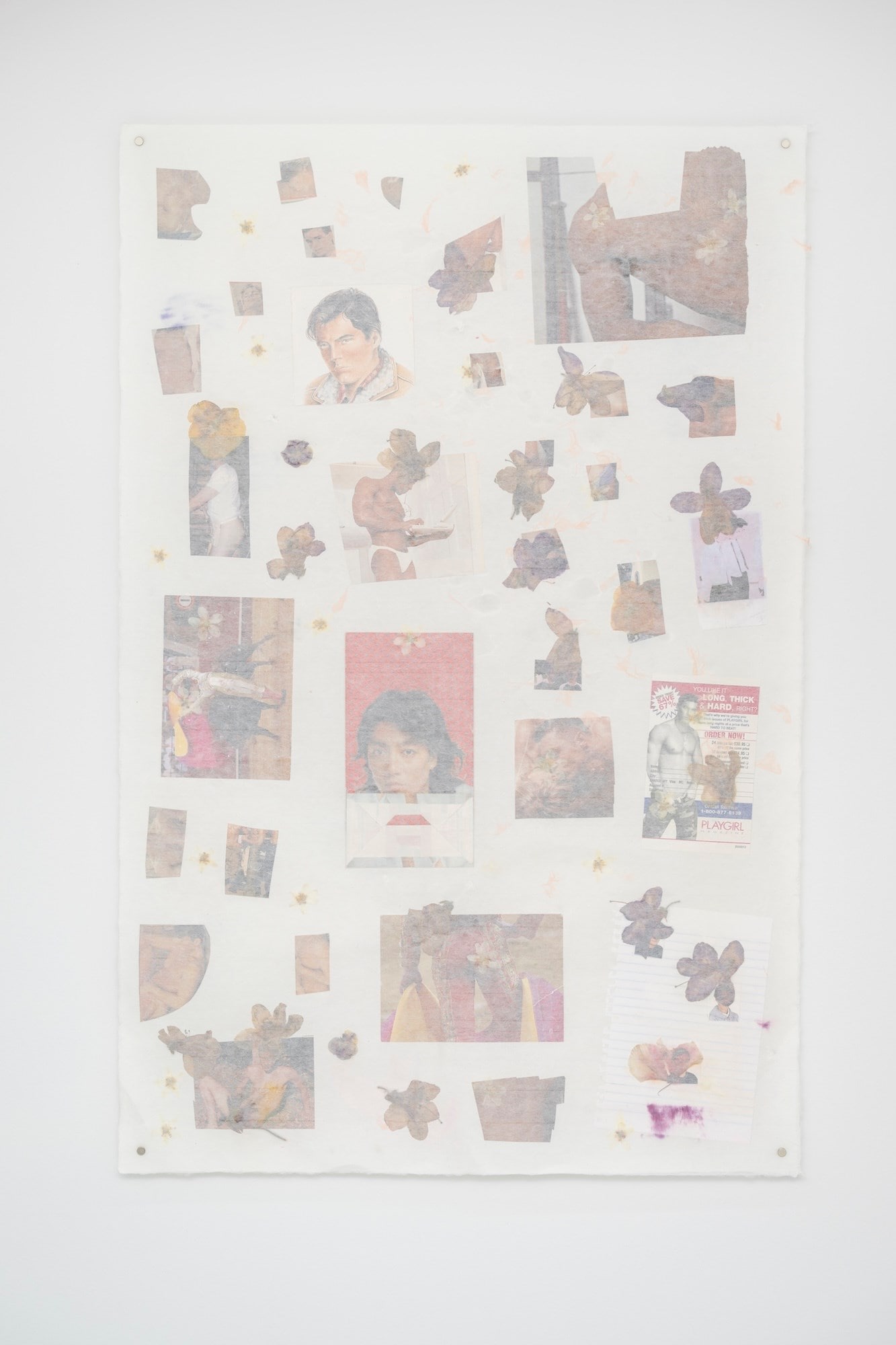

Before becoming one of fashion’s most original image-makers, Weir was a “normal” – if slightly sex-obsessed, she says – teenage girl who grew up the daughter of two toy-industry professionals in south London. The upstairs gallery presents a soft utopia that memorialises the carefree days of her youth, with new works that collage secret letters from school friends, mag cut-outs of buff men, and dried flowers under layers of pastel tissue. Made this year after a major house clear-out, they present a tactile, delicate side to her practice not seen before. Downstairs is the Weir we know better. A gut-punch awake from the daydream of her paper works, this space forces our gaze upon a second coming of age – post-35 – when women are told their bodies are beginning to expire, and the lightness of girlhood gives way to the weightier realities of adult life.

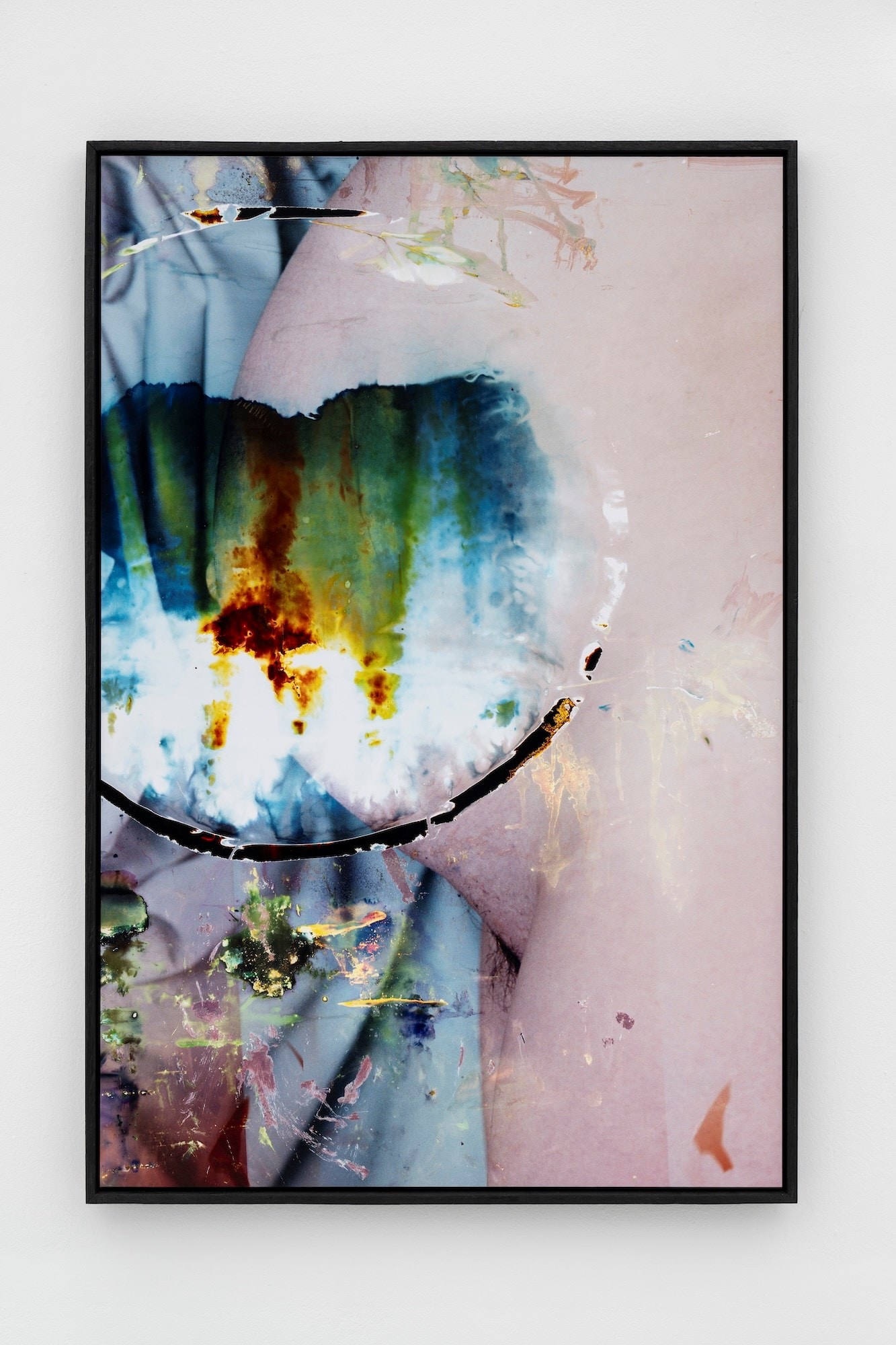

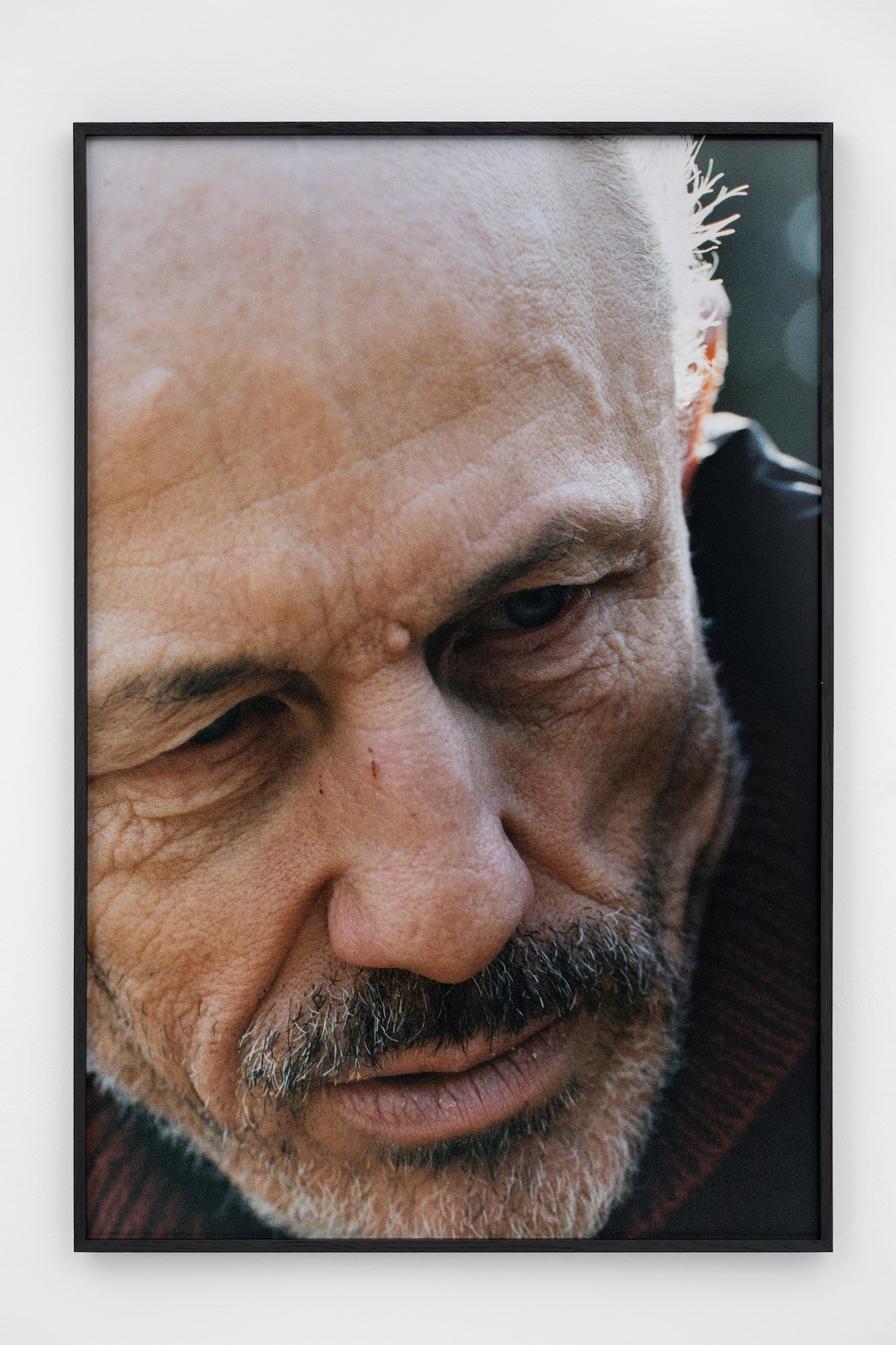

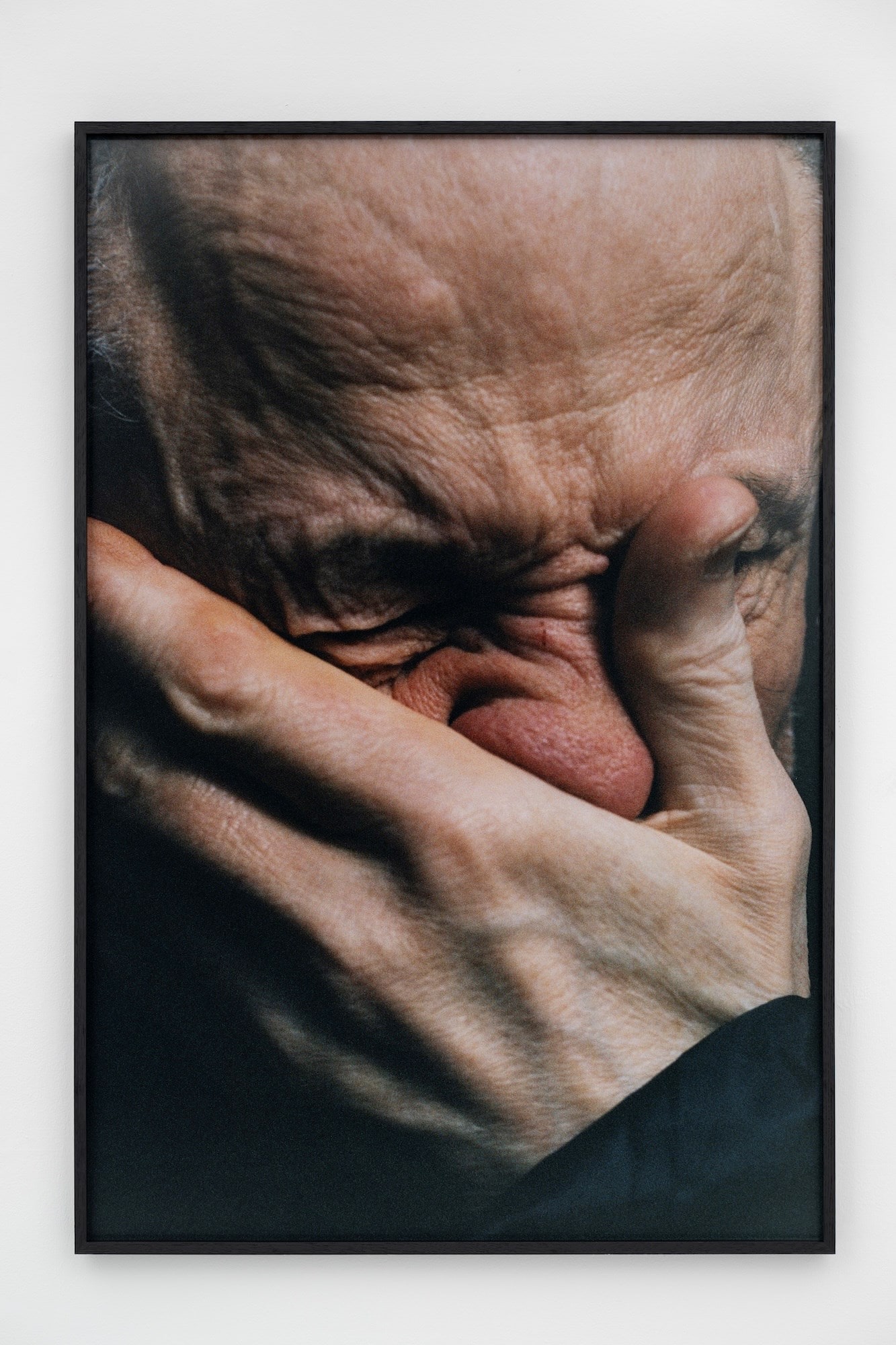

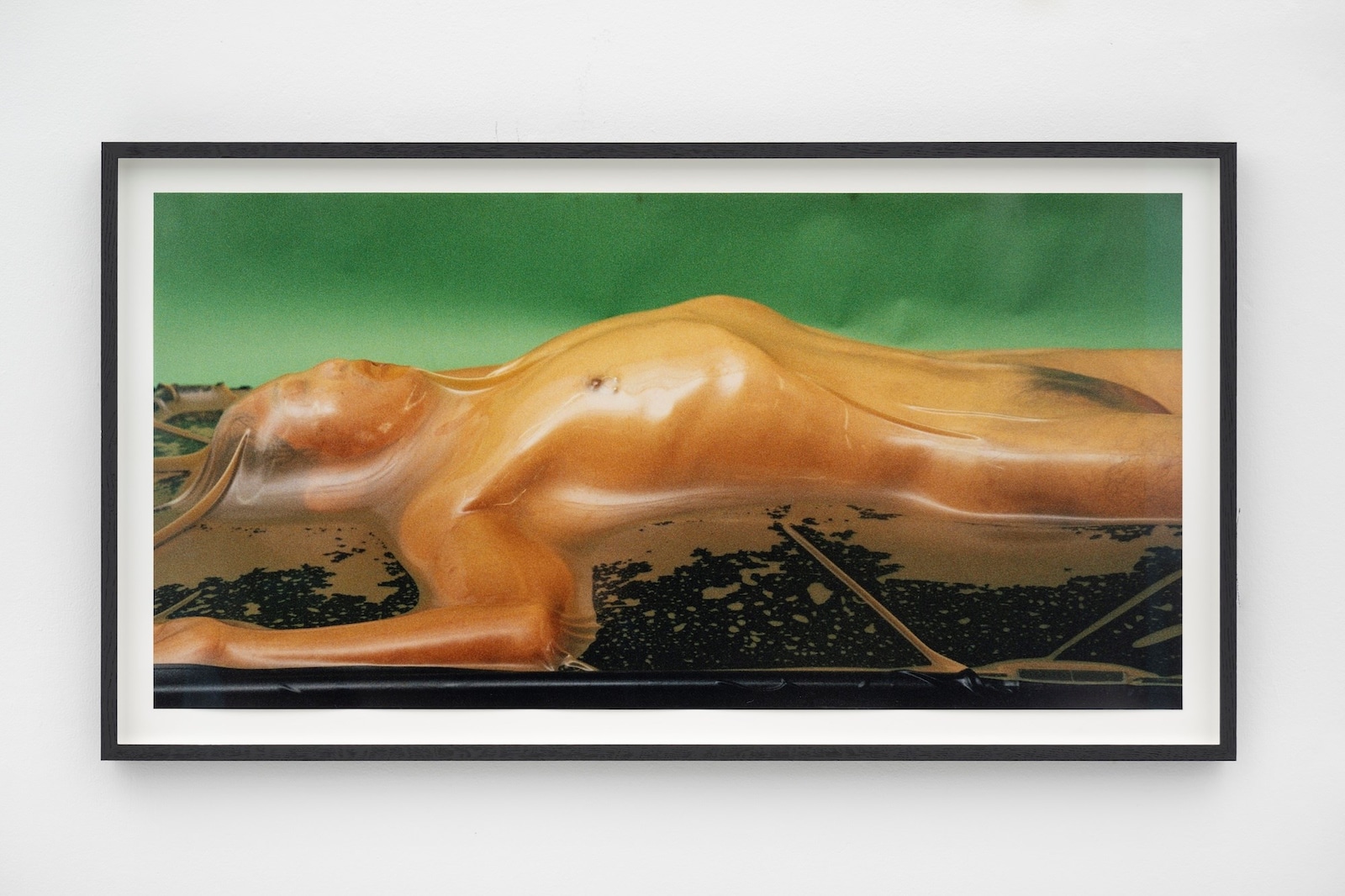

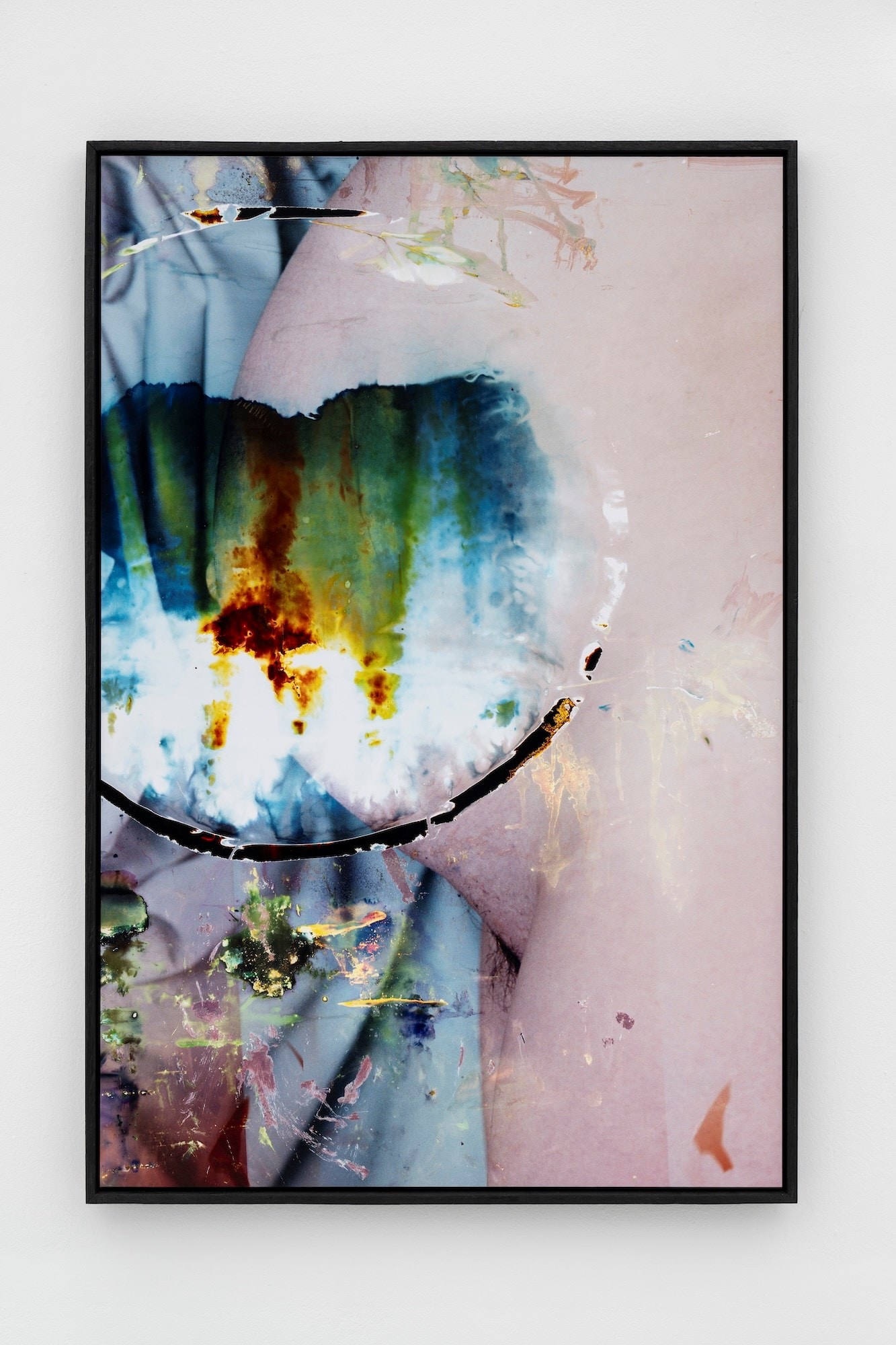

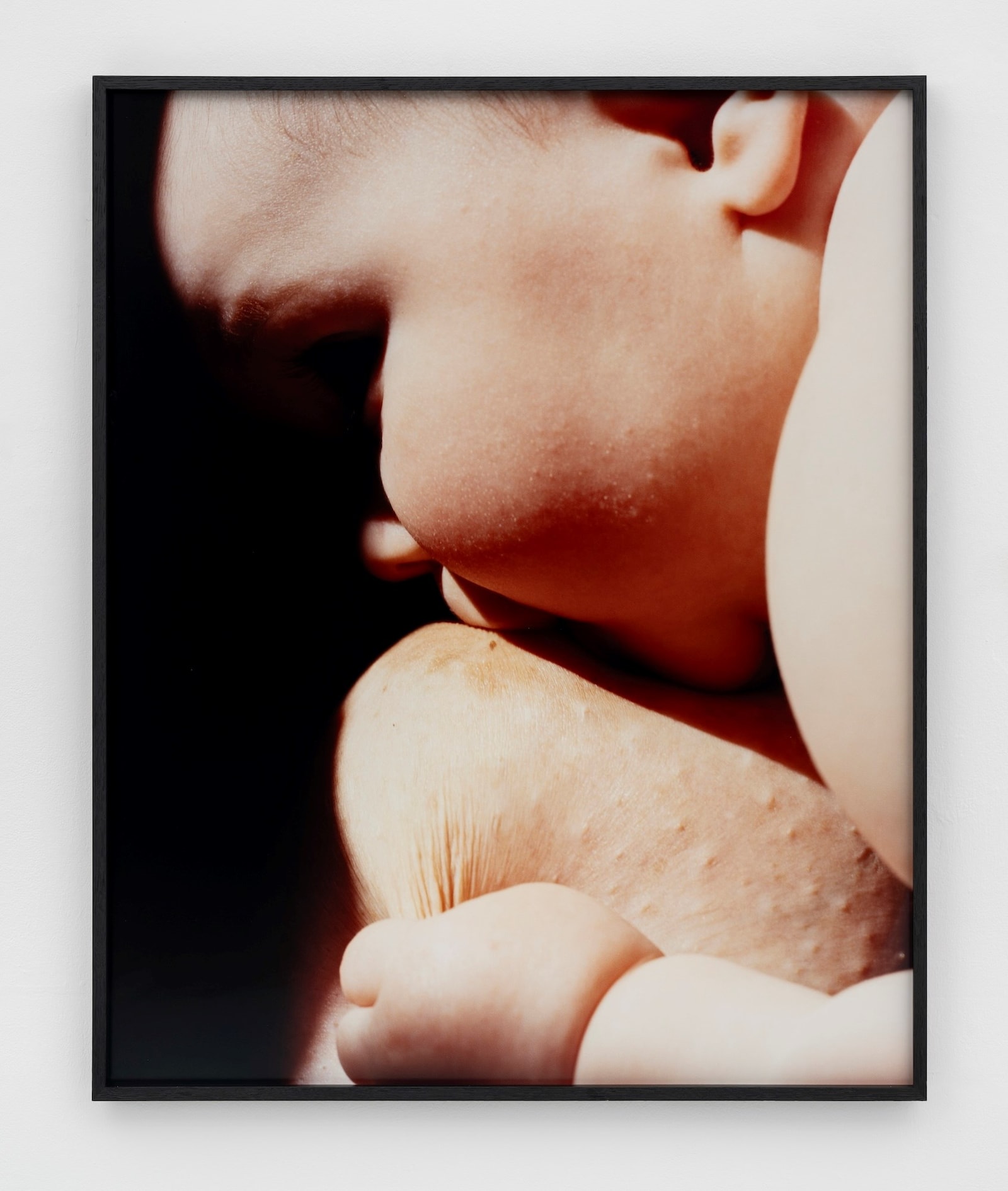

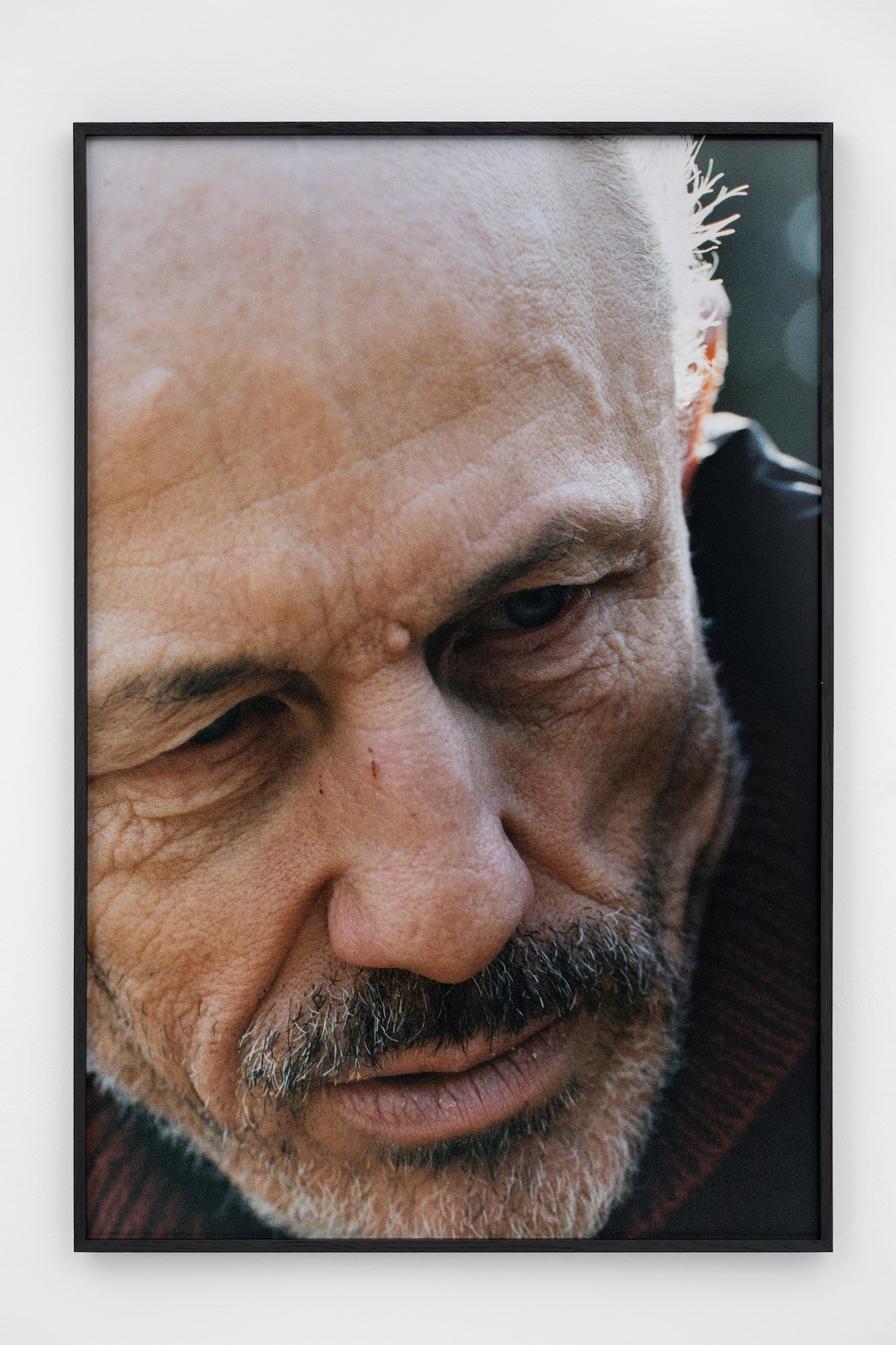

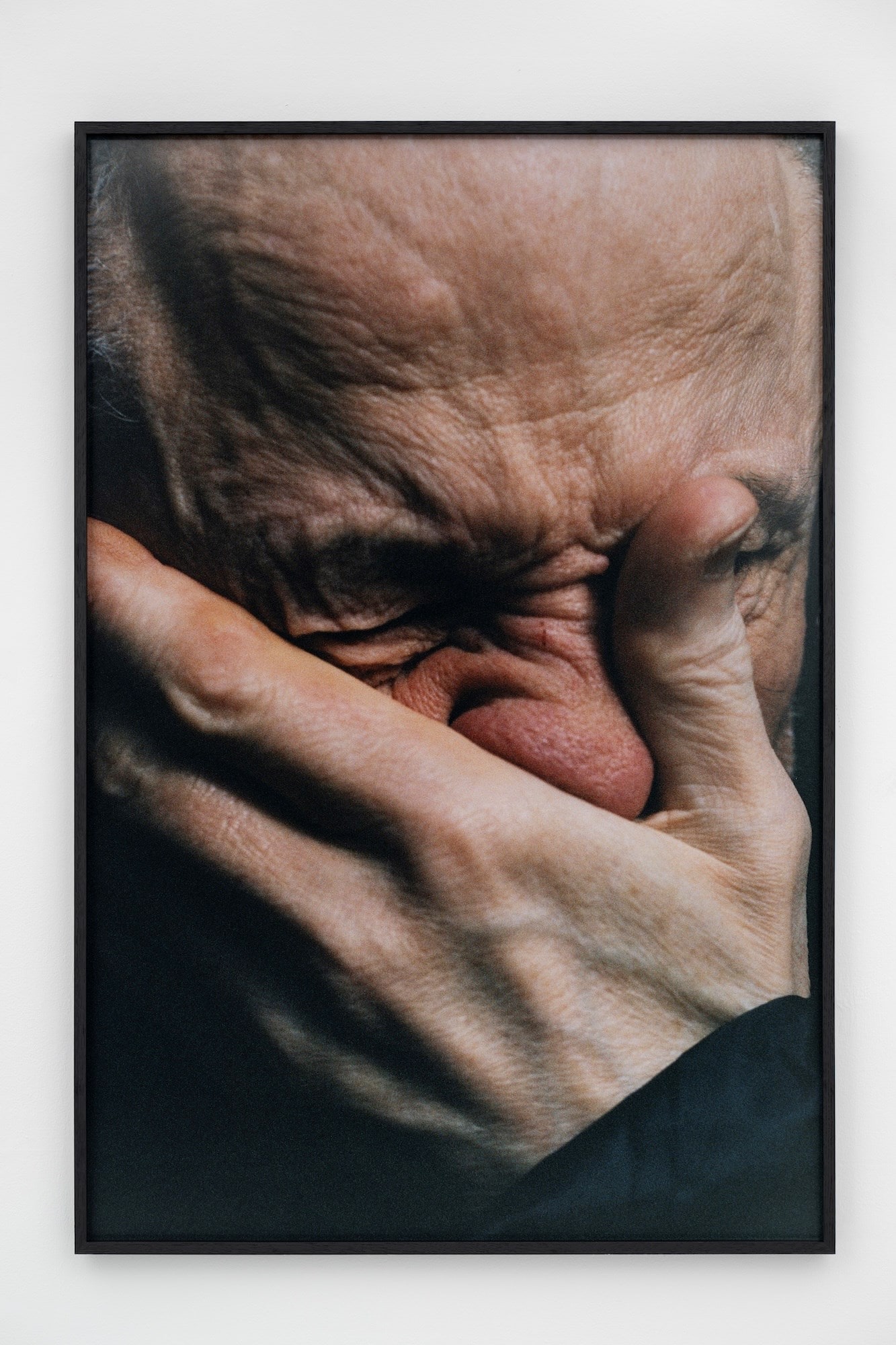

Tracing her growth as an artist, these works rove through 15 years of Weir’s multimedia genius to grasp forcefully at life’s biggest questions – birth, sex, and death – often collapsing the boundaries between them. Beautiful and disarming, the curation dares you to see the tenderness shared between a mother breastfeeding and a sex worker receiving a blowjob. Childbirth is captured with such intimate proximity it becomes as unknowable as her murky experiments, Sickos – a series started in lockdown after she decided against freezing her eggs, instead using the hormone chemicals in the darkroom. But it’s the most recent images in the show that are the most heart-wrenching – gentle portraits of her father, who has Benson’s disease (a rare form of Alzheimer’s), and no longer recognises her. They reveal the complexity of Weir’s second coming of age, where roles of care are amorphous, desire flickers in a thousand shades, and death is not as simple as a body stopping.

Here, she shares how while her garden may not be a paradise, it offers a chance to experience something more that’s perhaps more valuable – the awakening of becoming a woman:

Orla Brennan: Tell me about the exhibition title – The Garden makes me think of Eden, paradise and transformation. What does it mean to you?

Harley Weir: It’s exactly that. It’s kind of the idea of utopia or the end game. For me, I liked this idea that the journey to the garden is kind of a pipe dream. It’s something that I’ve always wanted to explore.

OB: The show is split into a teenage dreamworld upstairs, and a psychic awakening as a female artist downstairs. How did you decide to use the space?

HW: Upstairs is kind of like my first coming of age. It’s when you’re really excited about boys and life. They are hand-made paper works featuring letters written to me by my friends, around 2000 or 1999. I made sure they’re pretty illegible. You can’t really read anything.

OB: These paper works feel quite new for you – there’s a craftiness to the mix of textures with letters, the dried flowers and the memorabilia. What compelled you to make them?

HW: I’m basically a hoarder. I never threw these letters and artefacts from my teen years away. I’ve had a crazy couple of years and I was spring cleaning the other day, and I was like, ‘This shit needs to go.’ It was either burn them or make something from them.

OB: How do they capture the feeling of your teen years?

HW: I feel they are a time capsule of that time. I was looking at old magazines and they were so sexualised. It’s wild. There were even adverts for male escorts in them. I was like, Oh, I do not remember this.

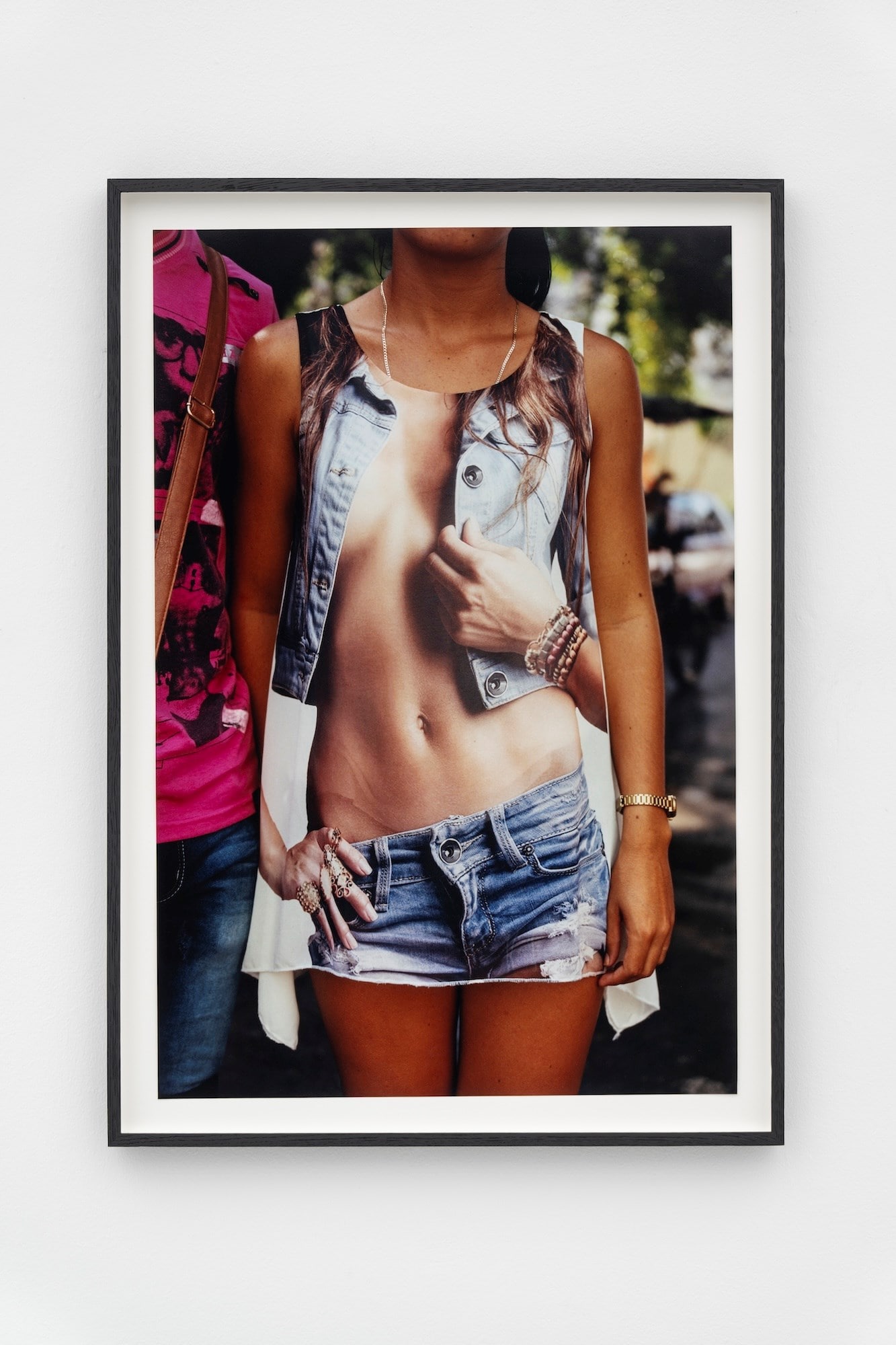

I’ve been working on a project called Men at Work, which looks at male sex workers who service women in different ways. It’s been really hard to find these people, so it was interesting seeing that brazenly out in the open.

OB: A few images from Men at Work are included downstairs, which has a much more intense feeling. What does that space represent to you?

HW: Downstairs is like my second coming of age, which for me comes after 35. It’s when the doctor’s reports say you’re starting to expire. A few years ago I decided to freeze my eggs and then changed my mind at the last minute. Some of the works that I used when I do this alchemy on photo paper use egg freezing chemicals and estrogen pills I melted down.

OB: You’ve also used blood, sperm, butterfly wings in that series, Sickos. What made you want to work with these more visceral materials? The effect is quite amazing.

OB: At first I just used spit to see what would happen. It kind of escalated from there. They are very laborious and horrible to make as you have to be in complete darkness. You’re always falling over all this crap and getting covered in stuff. That’s what was nice about the paper works – I needed some kind of outlet where I could be doing it in the daylight.

“There are so many films about coming of age as a teenager. But I feel like there’s another stage when you fully turn into an adult that’s less sung – especially for women” – Harley Weir

OB: Some of my favourite images are the ones themed on motherhood – the way you capture birth and breastfeeding is so intense. When did you get interested in that subject?

HW: Being a woman at a certain age, you get asked if you want to have kids a lot. It’s a question you constantly ask yourself. The older and older you get, the harder it is to answer. It’s just a big question.

OB: I guess it’s a huge crossroad, where which way you decide to go will change your entire life.

HW: It’s a big question. I always use photography as a form of knowledge. To me that’s what it is – a tool for me to learn. When I watched someone give birth, I thought I was going to be really terrified and think, ‘Oh, my God, it’s like an alien.’ But actually, it felt really natural watching a baby’s head come out of a vagina. I was like, I want to do that.

OB: Did it make you see motherhood differently?

I think there are so many ways to be a ‘mother’. As you get older, your parents need more looking after. In the show I put a picture of Mary next to a guy getting a blowjob. To me, the way he was holding her looked like a baby being cared for by a mother.

OB: Oh that is interesting that as a customer she wanted to pleasure him.

HW: It looks like she needs to be looked after, but actually she’s looking after him. There’s quite a holy light in the image. We were just in a really dark room and there was just like a big beam of natural sunlight on her face. It felt like a godly sort of moment.

OB: You’ve spoken before about questioning your own sense of desire after realising so much of what we see is made by men – images in magazines, porn, films, art. Has your work made you understand desire differently?

HW: It’s interesting, having done these projects with sex workers and things, it hasn’t changed my thoughts. It’s almost too late for me because of the constant feeding of those influences throughout my life.

But I do think there’s a difference between men and women’s bodies. For example, I might sexualise a pair of boobs I see on the street. At one point in my life, I thought that was because I’d watched so many things that were by men. Then I realised that actually, everyone’s first love is a breast.

OB: The newest images in the show are portraits of your dad, which you feel instantly drawn to as you enter the downstairs gallery. Why did you decide to include these?

HW: I almost didn’t put them in. My dad has something called Benson’s disease, which is not exactly Alzheimer’s, but it’s in the same bracket. You end up unable to see or understand anything. He doesn’t know who I am. I don’t know if you can tell in the images, but I’m very close to his face, and I think you can see that there’s no recognition of anyone there.

OB: That must be incredibly hard.

HW: I couldn’t take pictures of him for most of this journey so far, until recently. My mum and my sister finally had a funeral for his spirit, which might sound strange, but was really important. These pictures are about letting go. They mark a moment where I’ve not stopped caring, but I’ve understood that he’s no longer present.

OB: It’s really beautiful that they are part of the story of The Garden. The show covers these huge events of birth, desire, and death in such a powerful way.

HW: It’s that second coming of age, which is not very applauded. There are so many films about coming of age as a teenager. But I feel like there’s another stage when you fully turn into an adult that’s less sung – especially for women.

The Garden by Harley Weir is on view at Hannah Barry Gallery in London until 13 September 2025.

Harley Weir will be holding group support sessions at the gallery for individuals with loved ones affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Contact the gallery for more information.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageBed, 2007© Harley Weir Courtesy the artist and Hannah Barry Gallery, London, UK

Artists have long fallen under the spell of the garden. From Milton to Monet to Derek Jarman, the subject has inspired masterpieces of Edenic pleasure and stories shaped by the toil of growth. But Harley Weir’s take on the theme is unlike any you would have seen before. Spread across two floors of Hannah Barry Gallery in Peckham, her garden is less a pastoral sanctuary than a psychological arena – here she questions what it means to come of age as a woman.

Before becoming one of fashion’s most original image-makers, Weir was a “normal” – if slightly sex-obsessed, she says – teenage girl who grew up the daughter of two toy-industry professionals in south London. The upstairs gallery presents a soft utopia that memorialises the carefree days of her youth, with new works that collage secret letters from school friends, mag cut-outs of buff men, and dried flowers under layers of pastel tissue. Made this year after a major house clear-out, they present a tactile, delicate side to her practice not seen before. Downstairs is the Weir we know better. A gut-punch awake from the daydream of her paper works, this space forces our gaze upon a second coming of age – post-35 – when women are told their bodies are beginning to expire, and the lightness of girlhood gives way to the weightier realities of adult life.

Tracing her growth as an artist, these works rove through 15 years of Weir’s multimedia genius to grasp forcefully at life’s biggest questions – birth, sex, and death – often collapsing the boundaries between them. Beautiful and disarming, the curation dares you to see the tenderness shared between a mother breastfeeding and a sex worker receiving a blowjob. Childbirth is captured with such intimate proximity it becomes as unknowable as her murky experiments, Sickos – a series started in lockdown after she decided against freezing her eggs, instead using the hormone chemicals in the darkroom. But it’s the most recent images in the show that are the most heart-wrenching – gentle portraits of her father, who has Benson’s disease (a rare form of Alzheimer’s), and no longer recognises her. They reveal the complexity of Weir’s second coming of age, where roles of care are amorphous, desire flickers in a thousand shades, and death is not as simple as a body stopping.

Here, she shares how while her garden may not be a paradise, it offers a chance to experience something more that’s perhaps more valuable – the awakening of becoming a woman:

Orla Brennan: Tell me about the exhibition title – The Garden makes me think of Eden, paradise and transformation. What does it mean to you?

Harley Weir: It’s exactly that. It’s kind of the idea of utopia or the end game. For me, I liked this idea that the journey to the garden is kind of a pipe dream. It’s something that I’ve always wanted to explore.

OB: The show is split into a teenage dreamworld upstairs, and a psychic awakening as a female artist downstairs. How did you decide to use the space?

HW: Upstairs is kind of like my first coming of age. It’s when you’re really excited about boys and life. They are hand-made paper works featuring letters written to me by my friends, around 2000 or 1999. I made sure they’re pretty illegible. You can’t really read anything.

OB: These paper works feel quite new for you – there’s a craftiness to the mix of textures with letters, the dried flowers and the memorabilia. What compelled you to make them?

HW: I’m basically a hoarder. I never threw these letters and artefacts from my teen years away. I’ve had a crazy couple of years and I was spring cleaning the other day, and I was like, ‘This shit needs to go.’ It was either burn them or make something from them.

OB: How do they capture the feeling of your teen years?

HW: I feel they are a time capsule of that time. I was looking at old magazines and they were so sexualised. It’s wild. There were even adverts for male escorts in them. I was like, Oh, I do not remember this.

I’ve been working on a project called Men at Work, which looks at male sex workers who service women in different ways. It’s been really hard to find these people, so it was interesting seeing that brazenly out in the open.

OB: A few images from Men at Work are included downstairs, which has a much more intense feeling. What does that space represent to you?

HW: Downstairs is like my second coming of age, which for me comes after 35. It’s when the doctor’s reports say you’re starting to expire. A few years ago I decided to freeze my eggs and then changed my mind at the last minute. Some of the works that I used when I do this alchemy on photo paper use egg freezing chemicals and estrogen pills I melted down.

OB: You’ve also used blood, sperm, butterfly wings in that series, Sickos. What made you want to work with these more visceral materials? The effect is quite amazing.

OB: At first I just used spit to see what would happen. It kind of escalated from there. They are very laborious and horrible to make as you have to be in complete darkness. You’re always falling over all this crap and getting covered in stuff. That’s what was nice about the paper works – I needed some kind of outlet where I could be doing it in the daylight.

“There are so many films about coming of age as a teenager. But I feel like there’s another stage when you fully turn into an adult that’s less sung – especially for women” – Harley Weir

OB: Some of my favourite images are the ones themed on motherhood – the way you capture birth and breastfeeding is so intense. When did you get interested in that subject?

HW: Being a woman at a certain age, you get asked if you want to have kids a lot. It’s a question you constantly ask yourself. The older and older you get, the harder it is to answer. It’s just a big question.

OB: I guess it’s a huge crossroad, where which way you decide to go will change your entire life.

HW: It’s a big question. I always use photography as a form of knowledge. To me that’s what it is – a tool for me to learn. When I watched someone give birth, I thought I was going to be really terrified and think, ‘Oh, my God, it’s like an alien.’ But actually, it felt really natural watching a baby’s head come out of a vagina. I was like, I want to do that.

OB: Did it make you see motherhood differently?

I think there are so many ways to be a ‘mother’. As you get older, your parents need more looking after. In the show I put a picture of Mary next to a guy getting a blowjob. To me, the way he was holding her looked like a baby being cared for by a mother.

OB: Oh that is interesting that as a customer she wanted to pleasure him.

HW: It looks like she needs to be looked after, but actually she’s looking after him. There’s quite a holy light in the image. We were just in a really dark room and there was just like a big beam of natural sunlight on her face. It felt like a godly sort of moment.

OB: You’ve spoken before about questioning your own sense of desire after realising so much of what we see is made by men – images in magazines, porn, films, art. Has your work made you understand desire differently?

HW: It’s interesting, having done these projects with sex workers and things, it hasn’t changed my thoughts. It’s almost too late for me because of the constant feeding of those influences throughout my life.

But I do think there’s a difference between men and women’s bodies. For example, I might sexualise a pair of boobs I see on the street. At one point in my life, I thought that was because I’d watched so many things that were by men. Then I realised that actually, everyone’s first love is a breast.

OB: The newest images in the show are portraits of your dad, which you feel instantly drawn to as you enter the downstairs gallery. Why did you decide to include these?

HW: I almost didn’t put them in. My dad has something called Benson’s disease, which is not exactly Alzheimer’s, but it’s in the same bracket. You end up unable to see or understand anything. He doesn’t know who I am. I don’t know if you can tell in the images, but I’m very close to his face, and I think you can see that there’s no recognition of anyone there.

OB: That must be incredibly hard.

HW: I couldn’t take pictures of him for most of this journey so far, until recently. My mum and my sister finally had a funeral for his spirit, which might sound strange, but was really important. These pictures are about letting go. They mark a moment where I’ve not stopped caring, but I’ve understood that he’s no longer present.

OB: It’s really beautiful that they are part of the story of The Garden. The show covers these huge events of birth, desire, and death in such a powerful way.

HW: It’s that second coming of age, which is not very applauded. There are so many films about coming of age as a teenager. But I feel like there’s another stage when you fully turn into an adult that’s less sung – especially for women.

The Garden by Harley Weir is on view at Hannah Barry Gallery in London until 13 September 2025.

Harley Weir will be holding group support sessions at the gallery for individuals with loved ones affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Contact the gallery for more information.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.