Rewrite

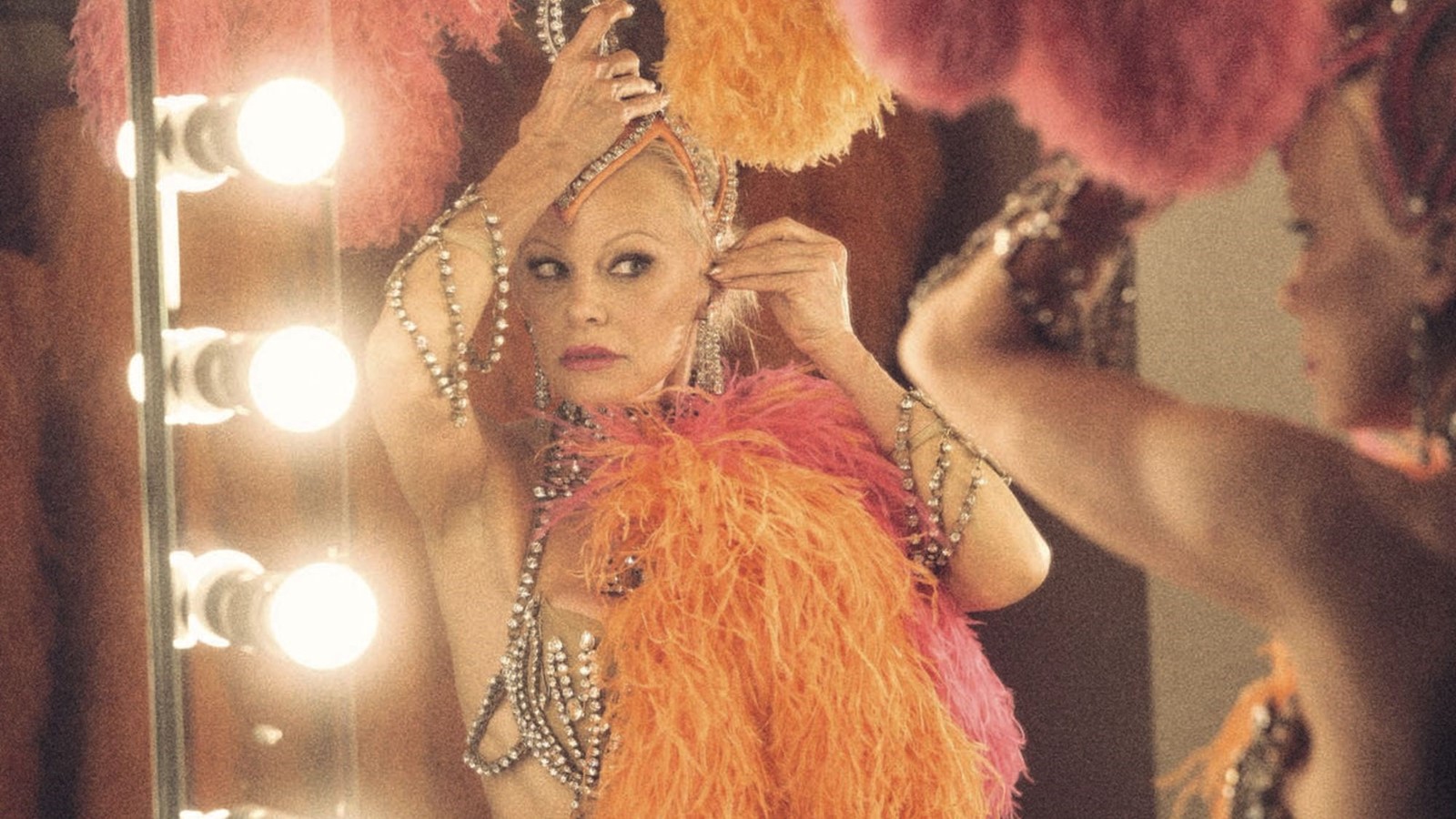

Lead ImageThe Last Showgirl, 2025(Film still)

In Gia Coppola’s The Last Showgirl, Shelly (Pamela Anderson) gives counsel to her estranged daughter Hannah (Billie Lourd), who has been told it will be too difficult for her to make it as a photographer: “Hard?” she says, “That’s the dumbest phrase anybody told anybody with a dream.” This mantra is a crucible for everything Shelly – the titular last showgirl – stands for: she is willing to make incredible sacrifices to claw out a life surrounded by beauty, creativity and craftsmanship.

Many films have centred on the struggle of being an artist, but few have focused on the everyday labour of artists like Shelly who are waged by entertainment companies, casinos and tourist attractions, and whose artistic excellence goes undervalued and underpaid. In The Last Showgirl, Shelly and the other remaining performers at Las Vegas’s Razzle Dazzle (based on the real-life Jubilee revue, closed in 2016) fight their way to the stage through blisters, torn costumes, quick changes, failed auditions and clouds of feathers. Shelly has been a fixture of the troop since its inception, and so when the show is scheduled to close, it is the tragic end of an era – both for her, now considered too old and demodé for new acts on the Strip, and for a historic artform and craft, exchanged for what is new, fast and cheap.

Shot on 16mm in just 18 days, Coppola’s third feature is an homage to the vulnerable efforts and labours of artists who have been discarded by an insatiable market. Where the churning circus of Vegas spits out its workers, however, The Last Showgirl foregrounds their humanity, tracing the bonds between Shelly and the dancers and crew who have shepherded each other through the gritty tribulations of showbiz.

Below, Gia Coppola and Pamela Anderson discuss the importance of love and community in making art, whether that be on set or when a film reaches its audience.

Gia Coppola: I used to be a photographer in college, and I naturally gravitated towards movie-making because it was more collaborative. It’s so important when making a movie to [make it feel like] family, but with The Last Showgirl we didn’t have a lot of rehearsal time, and we were prepping over the holidays – how do you build these deep relationships in a short amount of time? We were all very nervous about Jamie [Lee Curtis, who plays Shelly’s best friend Annette] but she’s such a legend, and knows how to come in full force and create that dynamic. She really set the tone, and did things like going to Pamela’s house and meeting [real-life] dancers, and her making her famous vegetable stew for all the younger girls – she was nourishing us with vegetables since we were in Vegas and [Vegas doesn’t do vegetables].

“I’ve had this beautiful, messy life and a lot to draw from. And I feel like all of that is what this film really meant to me” – Pamela Anderson

Pamela Anderson: I’d just played Roxie in Chicago on Broadway, and coming off of that felt like the warm-up for this film, to experience that backstage banter firsthand and know we were all in this together, that we all lifted each other up and that even if someone missed a line or a cue or anything, everyone was there for each other. That was really important for me to have experienced before doing this film. So that was how we all looked out for each other backstage [in the film] – that sisterhood is really important to make clear. Female relationships are complex. The mother-daughter story is there, and then the Vegas community itself was also very helpful. Dita Von Teese was a great advisor for us, and we had the dressers from the Jubilee come in, and everyone was just so excited that we were making this film! It was just a labour of love from top to bottom.

GC: I remember being in Vegas and always sort of curious: what is it like to live in this unusual city? At one point, a friend got pickpocketed, and we had to report it to the police, and it led us down the back channels of a casino, and I saw a sign for the “employee of the month”. And it just always stayed with me that there is this world that goes on to make the glitter and magic come alive. In a way, this is a movie about labour, and the systemic confinements for working women, especially, and working mothers who are creative. There are imbalances, and I don’t want to sort of dictate any sort of point of view on that. I just want to be observational.

PA: That’s something that Jamie talks about, too, when we’ve done interviews together, how even her character is a ‘bevertainer’ [a drinks waitress who performs as part of the job], and that was a way for the casino to get out of her being in a union. There’s all these little shortcuts, and especially dancers, you know, they’re just not treated that well. This is the backstage element: who are the people holding up the rhinestones? What do their daily lives look like? Who are all the people that make Las Vegas sparkle? It takes so many people, and we only see very, very few. I’ve always been curious about what happens backstage. So I thought that was a really nice element of it, and to show it authentically and with vulnerability. It was rare to be able to dive into those real human relationships backstage.

GC: I always think about how art, in a sense, is still a business. There’s obviously a lot of money involved just to make a vision happen and with that comes stakes. How do you find that balance of conveying something that is meaningful without being restricted by the consumerist ideas of what you’re also having to do? And Las Vegas is an interesting setting for that, because it is this land of showmanship, and what’s so heartbreaking about the Jubilee was that there was so much artistry and beauty that went into it. The level of production was massive, and that petered out over time because people’s tastes [became] more exploitative. You see the remnants of that. We’re using those real Bob Mackie costumes and you can’t recreate them: they put millions of dollars into the feathers alone.

PA: With [The Last Showgirl], there is a kind of magic between the audience and the film itself. There’s some kind of energy that’s going on. You’re doing your job if people can feel what you’re feeling. Under the surface, there’s so much simmering that we are not who we seem to be. Acting is a survival skill. We’re all doing it, but you can’t hide anything on screen. There are so many vulnerable and emotional elements to what it takes to be in this world and be looked at, objectified, but also to have a life.

I think I could draw that from my own experience. I mean, nobody wants to be defined by their worst moments, and I’ve had this beautiful, messy life and a lot to draw from. And I feel like all of that is what this film really meant to me. I just had so much empathy for the character. That’s why this kind of art form is really healing. You can talk to a therapist or your best friend all day long, but making a movie is more healing than anything I’ve ever experienced – to be able to put this feeling somewhere was important, and I think that’s what people are so drawn to with this film.

The Last Showgirl is in UK cinemas from February 28.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageThe Last Showgirl, 2025(Film still)

In Gia Coppola’s The Last Showgirl, Shelly (Pamela Anderson) gives counsel to her estranged daughter Hannah (Billie Lourd), who has been told it will be too difficult for her to make it as a photographer: “Hard?” she says, “That’s the dumbest phrase anybody told anybody with a dream.” This mantra is a crucible for everything Shelly – the titular last showgirl – stands for: she is willing to make incredible sacrifices to claw out a life surrounded by beauty, creativity and craftsmanship.

Many films have centred on the struggle of being an artist, but few have focused on the everyday labour of artists like Shelly who are waged by entertainment companies, casinos and tourist attractions, and whose artistic excellence goes undervalued and underpaid. In The Last Showgirl, Shelly and the other remaining performers at Las Vegas’s Razzle Dazzle (based on the real-life Jubilee revue, closed in 2016) fight their way to the stage through blisters, torn costumes, quick changes, failed auditions and clouds of feathers. Shelly has been a fixture of the troop since its inception, and so when the show is scheduled to close, it is the tragic end of an era – both for her, now considered too old and demodé for new acts on the Strip, and for a historic artform and craft, exchanged for what is new, fast and cheap.

Shot on 16mm in just 18 days, Coppola’s third feature is an homage to the vulnerable efforts and labours of artists who have been discarded by an insatiable market. Where the churning circus of Vegas spits out its workers, however, The Last Showgirl foregrounds their humanity, tracing the bonds between Shelly and the dancers and crew who have shepherded each other through the gritty tribulations of showbiz.

Below, Gia Coppola and Pamela Anderson discuss the importance of love and community in making art, whether that be on set or when a film reaches its audience.

Gia Coppola: I used to be a photographer in college, and I naturally gravitated towards movie-making because it was more collaborative. It’s so important when making a movie to [make it feel like] family, but with The Last Showgirl we didn’t have a lot of rehearsal time, and we were prepping over the holidays – how do you build these deep relationships in a short amount of time? We were all very nervous about Jamie [Lee Curtis, who plays Shelly’s best friend Annette] but she’s such a legend, and knows how to come in full force and create that dynamic. She really set the tone, and did things like going to Pamela’s house and meeting [real-life] dancers, and her making her famous vegetable stew for all the younger girls – she was nourishing us with vegetables since we were in Vegas and [Vegas doesn’t do vegetables].

“I’ve had this beautiful, messy life and a lot to draw from. And I feel like all of that is what this film really meant to me” – Pamela Anderson

Pamela Anderson: I’d just played Roxie in Chicago on Broadway, and coming off of that felt like the warm-up for this film, to experience that backstage banter firsthand and know we were all in this together, that we all lifted each other up and that even if someone missed a line or a cue or anything, everyone was there for each other. That was really important for me to have experienced before doing this film. So that was how we all looked out for each other backstage [in the film] – that sisterhood is really important to make clear. Female relationships are complex. The mother-daughter story is there, and then the Vegas community itself was also very helpful. Dita Von Teese was a great advisor for us, and we had the dressers from the Jubilee come in, and everyone was just so excited that we were making this film! It was just a labour of love from top to bottom.

GC: I remember being in Vegas and always sort of curious: what is it like to live in this unusual city? At one point, a friend got pickpocketed, and we had to report it to the police, and it led us down the back channels of a casino, and I saw a sign for the “employee of the month”. And it just always stayed with me that there is this world that goes on to make the glitter and magic come alive. In a way, this is a movie about labour, and the systemic confinements for working women, especially, and working mothers who are creative. There are imbalances, and I don’t want to sort of dictate any sort of point of view on that. I just want to be observational.

PA: That’s something that Jamie talks about, too, when we’ve done interviews together, how even her character is a ‘bevertainer’ [a drinks waitress who performs as part of the job], and that was a way for the casino to get out of her being in a union. There’s all these little shortcuts, and especially dancers, you know, they’re just not treated that well. This is the backstage element: who are the people holding up the rhinestones? What do their daily lives look like? Who are all the people that make Las Vegas sparkle? It takes so many people, and we only see very, very few. I’ve always been curious about what happens backstage. So I thought that was a really nice element of it, and to show it authentically and with vulnerability. It was rare to be able to dive into those real human relationships backstage.

GC: I always think about how art, in a sense, is still a business. There’s obviously a lot of money involved just to make a vision happen and with that comes stakes. How do you find that balance of conveying something that is meaningful without being restricted by the consumerist ideas of what you’re also having to do? And Las Vegas is an interesting setting for that, because it is this land of showmanship, and what’s so heartbreaking about the Jubilee was that there was so much artistry and beauty that went into it. The level of production was massive, and that petered out over time because people’s tastes [became] more exploitative. You see the remnants of that. We’re using those real Bob Mackie costumes and you can’t recreate them: they put millions of dollars into the feathers alone.

PA: With [The Last Showgirl], there is a kind of magic between the audience and the film itself. There’s some kind of energy that’s going on. You’re doing your job if people can feel what you’re feeling. Under the surface, there’s so much simmering that we are not who we seem to be. Acting is a survival skill. We’re all doing it, but you can’t hide anything on screen. There are so many vulnerable and emotional elements to what it takes to be in this world and be looked at, objectified, but also to have a life.

I think I could draw that from my own experience. I mean, nobody wants to be defined by their worst moments, and I’ve had this beautiful, messy life and a lot to draw from. And I feel like all of that is what this film really meant to me. I just had so much empathy for the character. That’s why this kind of art form is really healing. You can talk to a therapist or your best friend all day long, but making a movie is more healing than anything I’ve ever experienced – to be able to put this feeling somewhere was important, and I think that’s what people are so drawn to with this film.

The Last Showgirl is in UK cinemas from February 28.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.