Rewrite

To mark the passing of David Lynch, we revisit key moments in an oeuvre so singular it commanded its own adjective

Like no other director before, David Lynch conjured through his work a mesmerising blend of mystery, surrealism, sex and murder, all set amidst a suburban landscape. Lynch found that picture-postcard look of the perfect family so eerie that he suffused it with stories of incest, anger and frustration, drawing on noir tradition with his red lipstick-clad femme fatales and pitch-black surrealism in his frequently outlandish imagery. More often than not, his films provoked more questions than they did answers: What was the meaning of the man behind Winkie’s? The lady in the radiator? The FBI agent played by David Bowie who turned into a giant teapot? To mark the passing of a true genius of the form, we revisit seven iconic scenes from the Lynchian universe.

Possibly the most memorable scene amidst the darkness of Lost Highway (1997) is when Fred (Bill Pullman) attends a party and is approached by a man with a white painted face and a demonic twinkle in his eye (Robert Blake, oddly reminiscent of Joel Grey’s ghoulish MC in Cabaret). He tells Fred that he is currently in Fred’s house and proves it by asking him to call his own number. He also conveniently hands him a phone. It’s the grin of his red lips and the unwavering, expressionless stare that make it clear he knows something Fred doesn’t, but is desperately seeking answers to. While he talks to the man on the phone, who is also in front of him smiling, he is too perplexed to make any sense of the situation. When the man on the other end says, “Give me back my phone,” Fred hands it over to the guy, who walks off victoriously.

Curious to say it, but The Straight Story (1999) is actually a pretty straight story; an elderly man embarks on a cross-country road trip on his lawnmower to see his brother, who has recently suffered a stroke. Of course, this being Lynch, he encounters many strange occurrences along the way, the pick of the bunch being a woman who jumps screaming out of her car, having run over a deer. This seems strange enough, given the treeless prairie landscape she’s driving through. (“Where do they come from?” she wails.) But then comes the clincher: she has now killed 13 deers in seven weeks, but there is simply no other road to get her to work. “And I love deer!” she sobs as she drives off.

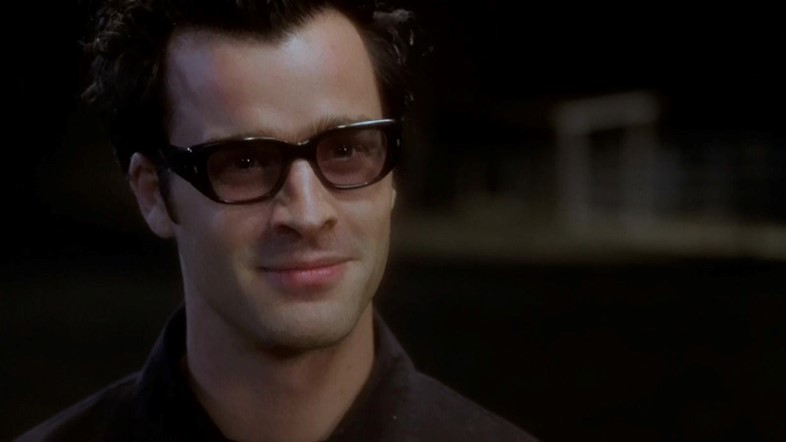

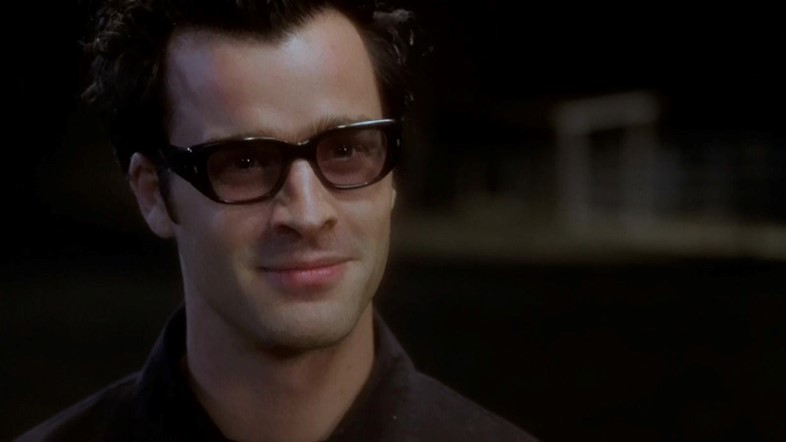

Director Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux) seems to pick up on the spectator’s stance by adopting a cynical position amidst the chaos of mystery that surrounds Mulholland Dr (2001). When he is summoned to meet a shadowy cowboy figure in the middle of the night, he just shrugs. Might as well go meet a cowboy now, this can’t get any weirder. But it can. The cowboy keeps a distance from him, hands in his pockets, which renders the encounter strangely serious despite his cowboy hat. We can instantly tell who gives the orders here. The cowboy tells him exactly what to do. “You say, ‘This is the girl. You will see me one more time if you do good, you will see me two more times if you do bad.’” And off he goes into the dark while Kesher stands there looking back at him, still covered in pink paint from a previous incident.

Many people associate Wild at Heart (1990) with a crazy dance scene in the club, passionate motel sex and of course the snakeskin jacket that gives Nicholas Cage the freedom to do whatever he wants. But there is another moment in which Lula’s intense love for Sailor is tested by a vile-looking Willem Dafoe. Whilst she is standing up to him in defence, he manages to get her so aroused that we see her fingers spreading wide open, a clear sign that she is about to orgasm, something which we have seen multiple times before while with Sailor. She fully submits herself to him eventually whispering “fuck me” just before he jumps back and yells, “Some day, honey, I will! But I gotta get going!” Leaving her humiliated, alone in the room.

In what is perhaps the most endlessly dissected scene from Lynch’s incendiary neo-noir, amateur sleuth Jeffrey (Kyle Maclachlan) locks himself in the closet of a woman he is ‘investigating’ and looks on as she is drawn into a bizarre sexual encounter. Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini) has to submit to a violent Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) who starts playing the baby while he is staring between her legs: “Mommy! Baby wants to fuck!” He tries to get himself high by inhaling gas and it becomes clear that he is impotent. He hits her in the face which turns her on, and what follows is her infamous red-lipped smile, a moment as disturbing as any in Lynch’s filmography. But this only works as a triangle. The scene is only complete because the young man sitting silently in the closet can be seen as the son or lover watching it all unfold, not making a sound. This closet scene is truly something Freudian.

Lynch’s fabled first feature reflected his fears of becoming a father; in it, a first-time dad (Jack Nance) is confronted with a new arrival that resembles a grotesque alien lifeform. Seeing how the child has changed the family dynamic to a point that is utterly surreal to him, he tries to play happy families even though he cannot comprehend what is going on. That’s before we get to the film’s most memorable character, the ‘lady in the radiator’. Shuffling daintily on stage like a nightmare Shirley Temple, she repeatedly sings “In heaven, everything is fine” until he approaches her, a lost man looking for solace in meaningless places.

Without doubt, the most iconic scene of Lynch’s entire filmography is the backwards-talking, twinkle-toed dwarf in the Red Room, an image that became so engrained in pop culture that even The Simpsons spoofed it. Appearing in episode three of the pioneering murder-mystery show, it was a moment that announced, in no uncertain terms, that this was Lynch’s universe and we were all invited. Incredibly, nearly 20 million people took him up on the offer, a transmission from another planet in the staid environment of 90s network television.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

To mark the passing of David Lynch, we revisit key moments in an oeuvre so singular it commanded its own adjective

Like no other director before, David Lynch conjured through his work a mesmerising blend of mystery, surrealism, sex and murder, all set amidst a suburban landscape. Lynch found that picture-postcard look of the perfect family so eerie that he suffused it with stories of incest, anger and frustration, drawing on noir tradition with his red lipstick-clad femme fatales and pitch-black surrealism in his frequently outlandish imagery. More often than not, his films provoked more questions than they did answers: What was the meaning of the man behind Winkie’s? The lady in the radiator? The FBI agent played by David Bowie who turned into a giant teapot? To mark the passing of a true genius of the form, we revisit seven iconic scenes from the Lynchian universe.

Possibly the most memorable scene amidst the darkness of Lost Highway (1997) is when Fred (Bill Pullman) attends a party and is approached by a man with a white painted face and a demonic twinkle in his eye (Robert Blake, oddly reminiscent of Joel Grey’s ghoulish MC in Cabaret). He tells Fred that he is currently in Fred’s house and proves it by asking him to call his own number. He also conveniently hands him a phone. It’s the grin of his red lips and the unwavering, expressionless stare that make it clear he knows something Fred doesn’t, but is desperately seeking answers to. While he talks to the man on the phone, who is also in front of him smiling, he is too perplexed to make any sense of the situation. When the man on the other end says, “Give me back my phone,” Fred hands it over to the guy, who walks off victoriously.

Curious to say it, but The Straight Story (1999) is actually a pretty straight story; an elderly man embarks on a cross-country road trip on his lawnmower to see his brother, who has recently suffered a stroke. Of course, this being Lynch, he encounters many strange occurrences along the way, the pick of the bunch being a woman who jumps screaming out of her car, having run over a deer. This seems strange enough, given the treeless prairie landscape she’s driving through. (“Where do they come from?” she wails.) But then comes the clincher: she has now killed 13 deers in seven weeks, but there is simply no other road to get her to work. “And I love deer!” she sobs as she drives off.

Director Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux) seems to pick up on the spectator’s stance by adopting a cynical position amidst the chaos of mystery that surrounds Mulholland Dr (2001). When he is summoned to meet a shadowy cowboy figure in the middle of the night, he just shrugs. Might as well go meet a cowboy now, this can’t get any weirder. But it can. The cowboy keeps a distance from him, hands in his pockets, which renders the encounter strangely serious despite his cowboy hat. We can instantly tell who gives the orders here. The cowboy tells him exactly what to do. “You say, ‘This is the girl. You will see me one more time if you do good, you will see me two more times if you do bad.’” And off he goes into the dark while Kesher stands there looking back at him, still covered in pink paint from a previous incident.

Many people associate Wild at Heart (1990) with a crazy dance scene in the club, passionate motel sex and of course the snakeskin jacket that gives Nicholas Cage the freedom to do whatever he wants. But there is another moment in which Lula’s intense love for Sailor is tested by a vile-looking Willem Dafoe. Whilst she is standing up to him in defence, he manages to get her so aroused that we see her fingers spreading wide open, a clear sign that she is about to orgasm, something which we have seen multiple times before while with Sailor. She fully submits herself to him eventually whispering “fuck me” just before he jumps back and yells, “Some day, honey, I will! But I gotta get going!” Leaving her humiliated, alone in the room.

In what is perhaps the most endlessly dissected scene from Lynch’s incendiary neo-noir, amateur sleuth Jeffrey (Kyle Maclachlan) locks himself in the closet of a woman he is ‘investigating’ and looks on as she is drawn into a bizarre sexual encounter. Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini) has to submit to a violent Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) who starts playing the baby while he is staring between her legs: “Mommy! Baby wants to fuck!” He tries to get himself high by inhaling gas and it becomes clear that he is impotent. He hits her in the face which turns her on, and what follows is her infamous red-lipped smile, a moment as disturbing as any in Lynch’s filmography. But this only works as a triangle. The scene is only complete because the young man sitting silently in the closet can be seen as the son or lover watching it all unfold, not making a sound. This closet scene is truly something Freudian.

Lynch’s fabled first feature reflected his fears of becoming a father; in it, a first-time dad (Jack Nance) is confronted with a new arrival that resembles a grotesque alien lifeform. Seeing how the child has changed the family dynamic to a point that is utterly surreal to him, he tries to play happy families even though he cannot comprehend what is going on. That’s before we get to the film’s most memorable character, the ‘lady in the radiator’. Shuffling daintily on stage like a nightmare Shirley Temple, she repeatedly sings “In heaven, everything is fine” until he approaches her, a lost man looking for solace in meaningless places.

Without doubt, the most iconic scene of Lynch’s entire filmography is the backwards-talking, twinkle-toed dwarf in the Red Room, an image that became so engrained in pop culture that even The Simpsons spoofed it. Appearing in episode three of the pioneering murder-mystery show, it was a moment that announced, in no uncertain terms, that this was Lynch’s universe and we were all invited. Incredibly, nearly 20 million people took him up on the offer, a transmission from another planet in the staid environment of 90s network television.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.