Rewrite

目次

- 1 From Imperfect three image films by Jonas Mekas to Ingel Vaikla’s Moi Aussi, Je Regarde, Hannah Lack shares her highlights from the festival’s rich line-up

- 2 May ’68 in ‘78 by Michel Auder

- 3 Imperfect three image films by Jonas Mekas

- 4 L’Automne by Marcel Hanoun

- 5 Moi Aussi, Je Regarde by Ingel Vaikla and E for Eileen by Gerard & Kelly

- 6 From Imperfect three image films by Jonas Mekas to Ingel Vaikla’s Moi Aussi, Je Regarde, Hannah Lack shares her highlights from the festival’s rich line-up

- 7 May ’68 in ‘78 by Michel Auder

- 8 Imperfect three image films by Jonas Mekas

- 9 L’Automne by Marcel Hanoun

- 10 Moi Aussi, Je Regarde by Ingel Vaikla and E for Eileen by Gerard & Kelly

From Imperfect three image films by Jonas Mekas to Ingel Vaikla’s Moi Aussi, Je Regarde, Hannah Lack shares her highlights from the festival’s rich line-up

A Swiss resort encircled by craggy snow-capped peaks, St Moritz has an illustrious film history. Hitchcock staged a murder here in The Man Who Knew Too Much and conceived The Birds in the Palace Hotel as he watched a flock fly over its turreted roof. Charlie Chaplin once landed his plane on the town’s frozen lake and Brigitte Bardot regularly skied its slopes. For the last three years, the Saint Moritz Art and Film Festival has been driving that celluloid tradition forward in radical, uncompromising new directions with an annual programme that stretches into the small hours and feels no obligation to blend quietly into the town’s fairytale surroundings (see the festival’s closing night premiere, Paul McCarthy’s twisted take on Heidi’s Alpine existence).

This year, directors came from across the globe – Mongolia, Argentina, India and the US – to gather in the 100-seat art-deco Scala cinema and sink their teeth into a meticulously curated line-up of art, film and conversation helmed by Stefano Rabolli Pansera, SMAFF’s indefatigable artistic director: “The Engadin Valley is a magical place,” he says in a break between screenings. “It’s an oasis where you are in the centre of Europe yet detached. I think this provides an ideal place to get critical distance from who we are and what we are living through. This is the reason why Thomas Mann set The Magic Mountain nearby, why so many artists have come here, from Gerhard Richter to Julian Schnabel to Nietzsche.”

SMAFF’s third iteration has a theme of “Meanwhile Histories”, and makes space for a trove of hidden stories and overlooked communities: “History is always written by power,” Pansera says. “We want to deconstruct the main narrative and offer a different point of view.” This year those stories have a vast reach – from the railroads of the Caucasus to the oil pumps of Texas, from a watchtower in Cyprus to a volcano in Hawaii. But the festival is also singular in its intimacy: over its five-day run, we hear tales of the mysterious and murderous history of a modernist Cote d’Azur villa from artist duo Gerard & Kelly, whose beguiling new film was shot inside the house; chatted to young curator (and Dazed 100 alumnus) Róisín Tapponi about her debut, art world-set novel, soon to be made into a feature by Martine Syms; and listened to French filmmaker Michel Auder reminisce about his unruly years at the Chelsea Hotel, over drinks at a mountainside bar.

Auder’s film May ’68 in ’78 was one of the standouts of the festival, as was his cheerfully nonconformist presence – an obsessive chronicler of life around him, he could be spied still shooting his film diaries at the closing ceremony, held inside the town’s flame-lit Dracula Club. That night prizes went to three distinctive voices: Argentinian filmmaker Eduardo Williams, whose short Parsi is set in the queer and trans community of Guinea-Bissau; Seoul-born Young-jun Tak, who juxtaposes male dancers in a Berlin cruising ground and a troupe of Spanish Legion soldiers in Love Your Clean Feet on Thursday; and Aura Satz, whose visceral sonic collage Pre-emptive Listening is a meditation on emergency sirens in a crisis-driven world.

Here, we choose five more from the festival’s rich line-up:

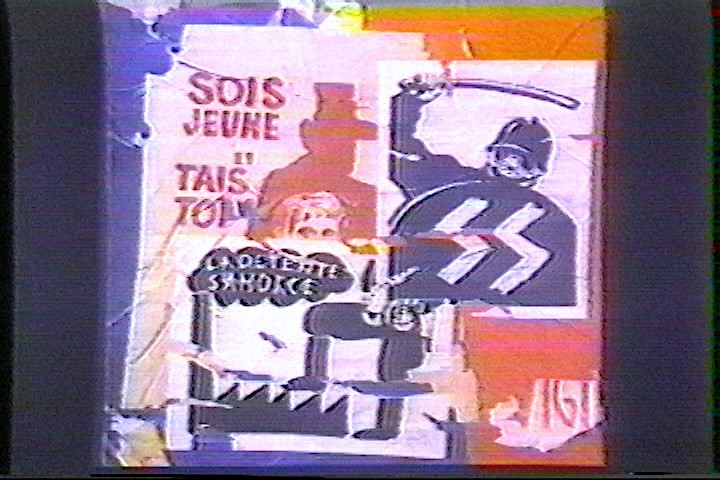

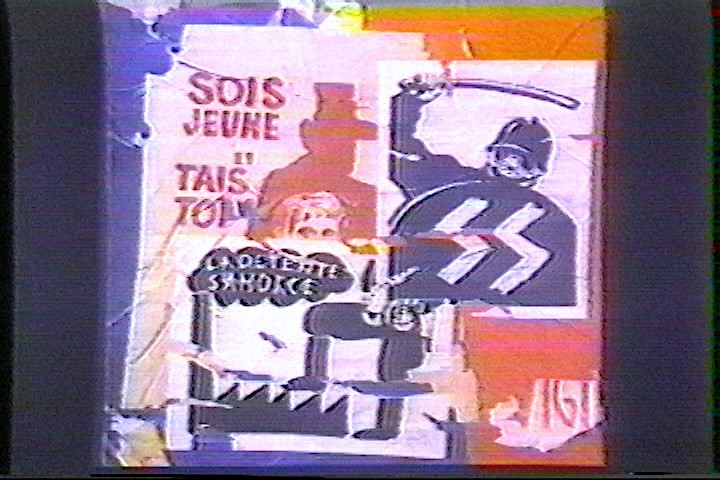

May ’68 in ‘78 by Michel Auder

Auder dismantles the clichés that tend to calcify around seismic events by approaching the French strikes and street battles of May ’68 sideways. The experimental filmmaker was on the barricades shooting footage of the student revolt that fabled month but lost it all when he left Paris soon after. (He met Nico and Warhol superstar Viva one night on a Parisian street, moved to New York and married the latter). Ten years later, Auder returned to gather a patchwork of memories from the protests – informal reel-to-reels of friends, artists, police officers and passersby whose recollections range from the personal to the political to the surreal. There are tales of the roast chickens sent out to feed protesters; the 12-year-old who popped out to buy croissants and came back with Mao’s Little Red Book; and the guests at a glitzy Right Bank hotel who locked up their jewels in uneasy silence. Artist Jean Tinguely wasn’t in the country, so he offers memories of a liaison between two elephants in Amsterdam zoo. Interpretations of the significance of May ’68 have seesawed between groundshaking revolution and poetic daydream; Auder’s freewheeling exploration is much more about the stories we tell ourselves.

Imperfect three image films by Jonas Mekas

Like Auder, the godfather of American avant-garde cinema Jonas Mekas was a compulsive film diarist. Whether he was documenting Warhol slowly munching fruit, Salvador Dalí covering models with whipped cream, or the Velvet Underground’s first gig at a psychiatrist’s convention, his films reach out and place his viewers beside him, allowing people, places, days and nights to breathe again. An irrepressible ringleader at the centre of New York counterculture since his arrival from war-torn Lithuania in 1949, Mekas spent a lifetime in the trenches of experimental cinema, an exile constructing himself a new narrative with his Bolex. His Imperfect three image films, pulled from Mekas’ sprawling collection of autobiographical vignettes is his kaleidoscopic take on time and memory, flickering moving-image haikus that offer “brief glimpses of beauty” as he liked to put it.

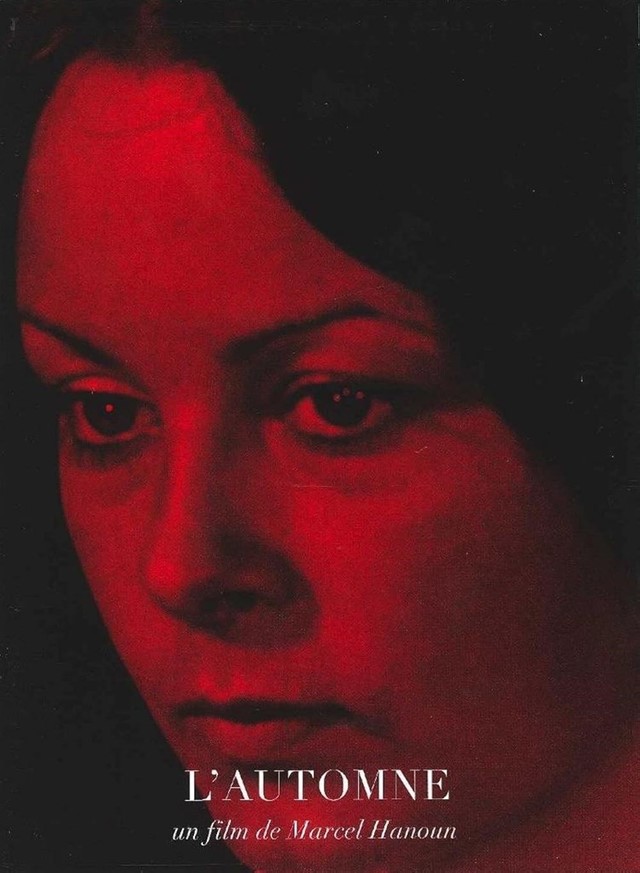

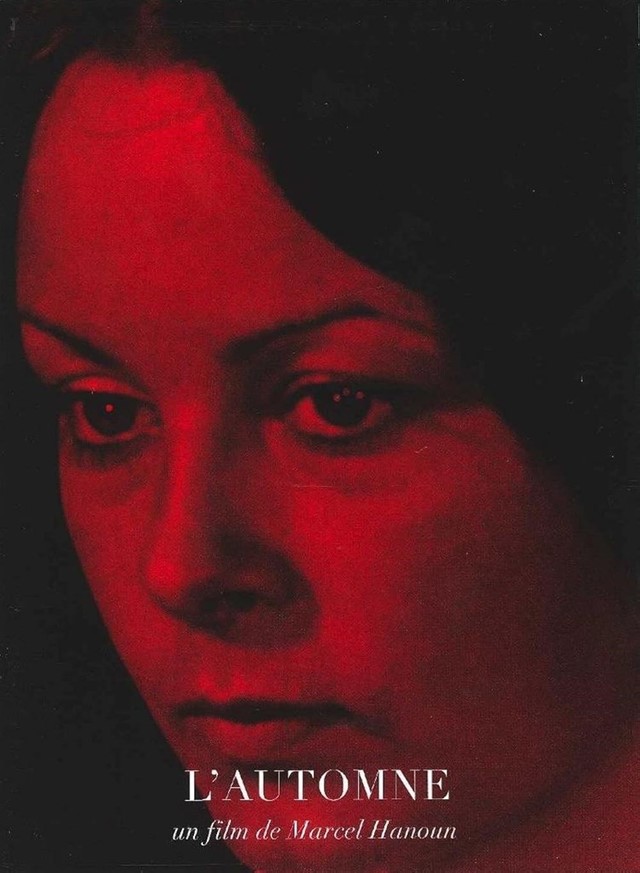

L’Automne by Marcel Hanoun

Mekas would have been pleased that this 1972 puzzle-box of a movie from underappreciated Tunisian-born director Hanoun has another champion. It was brought to the festival by young Irish-Iraqi film curator and writer Róisín Tapponi – also the founder of Shasha Movies, an independent streaming service showcasing Southwest Asian and North African cinema. L’Automne is the third of Hanoun’s four “seasons” and trains its camera on two faces – a film director and an editor in the process of cutting together a film we never see – as they talk movies, art and politics. Hanoun had one foot in the French New Wave but carved a path that was adamantly his own; he slyly pokes fun at the movement’s pretensions as he untangles ideas around how we watch films – and how we watch each other. As Tapponi said after the screening, along with the role that women played in the French New Wave, the sidelined Hanoun is long overdue a reappraisal.

Moi Aussi, Je Regarde by Ingel Vaikla and E for Eileen by Gerard & Kelly

Two films at the festival unearth the stories buried in modernist Cote d’Azur gems: Moi Aussi, Je Regarde focuses on Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse in Marseille, his vertical village on stilts that sits between the mountains and the Mediterranean. Ingel Vaikla approaches the architect’s UNESCO-stamped masterpiece (or “house of madmen” to its critics) through its female inhabitants as they skate between its giant stilts and explore its nine “streets” in a riposte to often heavily masculine notions of modernism. Paris-based American artists Gerard & Kelly meanwhile are working on a series of films set amid iconic French architecture.

At the festival they screened their latest, E for Eileen, which draws on the overlooked, subversive life of architect Eileen Gray (played in their film by British actor Nikki Amuka-Bird). Shot entirely at Gray’s ingenious villa E-1027 in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, it’s a fictional take on Gray’s final day there – she mysteriously quit the house in 1932 and never returned – as a raucous crowd of friends and lovers descend on her compact modernist haven. Post-Gray, the house went on to have a strange and chequered history, weathering squatters, murders and Nazis – and defacement by a jealous Le Corbusier, who painted murals across its white walls against Gray’s wishes. Today the villa has been restored to its exquisite 1929 state and the artists’ film makes clear how Gray’s radical-for-the time bisexuality and rejection of society’s rigid confines was reflected in her design. A marvel of foldable tables, pivoting drawers, adjustable lamps and sliding shutters, it’s a fluid and unconventional masterwork perched on a Riviera cliff face.

Find out more about St. Moritz Art Film Festival here.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

From Imperfect three image films by Jonas Mekas to Ingel Vaikla’s Moi Aussi, Je Regarde, Hannah Lack shares her highlights from the festival’s rich line-up

A Swiss resort encircled by craggy snow-capped peaks, St Moritz has an illustrious film history. Hitchcock staged a murder here in The Man Who Knew Too Much and conceived The Birds in the Palace Hotel as he watched a flock fly over its turreted roof. Charlie Chaplin once landed his plane on the town’s frozen lake and Brigitte Bardot regularly skied its slopes. For the last three years, the Saint Moritz Art and Film Festival has been driving that celluloid tradition forward in radical, uncompromising new directions with an annual programme that stretches into the small hours and feels no obligation to blend quietly into the town’s fairytale surroundings (see the festival’s closing night premiere, Paul McCarthy’s twisted take on Heidi’s Alpine existence).

This year, directors came from across the globe – Mongolia, Argentina, India and the US – to gather in the 100-seat art-deco Scala cinema and sink their teeth into a meticulously curated line-up of art, film and conversation helmed by Stefano Rabolli Pansera, SMAFF’s indefatigable artistic director: “The Engadin Valley is a magical place,” he says in a break between screenings. “It’s an oasis where you are in the centre of Europe yet detached. I think this provides an ideal place to get critical distance from who we are and what we are living through. This is the reason why Thomas Mann set The Magic Mountain nearby, why so many artists have come here, from Gerhard Richter to Julian Schnabel to Nietzsche.”

SMAFF’s third iteration has a theme of “Meanwhile Histories”, and makes space for a trove of hidden stories and overlooked communities: “History is always written by power,” Pansera says. “We want to deconstruct the main narrative and offer a different point of view.” This year those stories have a vast reach – from the railroads of the Caucasus to the oil pumps of Texas, from a watchtower in Cyprus to a volcano in Hawaii. But the festival is also singular in its intimacy: over its five-day run, we hear tales of the mysterious and murderous history of a modernist Cote d’Azur villa from artist duo Gerard & Kelly, whose beguiling new film was shot inside the house; chatted to young curator (and Dazed 100 alumnus) Róisín Tapponi about her debut, art world-set novel, soon to be made into a feature by Martine Syms; and listened to French filmmaker Michel Auder reminisce about his unruly years at the Chelsea Hotel, over drinks at a mountainside bar.

Auder’s film May ’68 in ’78 was one of the standouts of the festival, as was his cheerfully nonconformist presence – an obsessive chronicler of life around him, he could be spied still shooting his film diaries at the closing ceremony, held inside the town’s flame-lit Dracula Club. That night prizes went to three distinctive voices: Argentinian filmmaker Eduardo Williams, whose short Parsi is set in the queer and trans community of Guinea-Bissau; Seoul-born Young-jun Tak, who juxtaposes male dancers in a Berlin cruising ground and a troupe of Spanish Legion soldiers in Love Your Clean Feet on Thursday; and Aura Satz, whose visceral sonic collage Pre-emptive Listening is a meditation on emergency sirens in a crisis-driven world.

Here, we choose five more from the festival’s rich line-up:

May ’68 in ‘78 by Michel Auder

Auder dismantles the clichés that tend to calcify around seismic events by approaching the French strikes and street battles of May ’68 sideways. The experimental filmmaker was on the barricades shooting footage of the student revolt that fabled month but lost it all when he left Paris soon after. (He met Nico and Warhol superstar Viva one night on a Parisian street, moved to New York and married the latter). Ten years later, Auder returned to gather a patchwork of memories from the protests – informal reel-to-reels of friends, artists, police officers and passersby whose recollections range from the personal to the political to the surreal. There are tales of the roast chickens sent out to feed protesters; the 12-year-old who popped out to buy croissants and came back with Mao’s Little Red Book; and the guests at a glitzy Right Bank hotel who locked up their jewels in uneasy silence. Artist Jean Tinguely wasn’t in the country, so he offers memories of a liaison between two elephants in Amsterdam zoo. Interpretations of the significance of May ’68 have seesawed between groundshaking revolution and poetic daydream; Auder’s freewheeling exploration is much more about the stories we tell ourselves.

Imperfect three image films by Jonas Mekas

Like Auder, the godfather of American avant-garde cinema Jonas Mekas was a compulsive film diarist. Whether he was documenting Warhol slowly munching fruit, Salvador Dalí covering models with whipped cream, or the Velvet Underground’s first gig at a psychiatrist’s convention, his films reach out and place his viewers beside him, allowing people, places, days and nights to breathe again. An irrepressible ringleader at the centre of New York counterculture since his arrival from war-torn Lithuania in 1949, Mekas spent a lifetime in the trenches of experimental cinema, an exile constructing himself a new narrative with his Bolex. His Imperfect three image films, pulled from Mekas’ sprawling collection of autobiographical vignettes is his kaleidoscopic take on time and memory, flickering moving-image haikus that offer “brief glimpses of beauty” as he liked to put it.

L’Automne by Marcel Hanoun

Mekas would have been pleased that this 1972 puzzle-box of a movie from underappreciated Tunisian-born director Hanoun has another champion. It was brought to the festival by young Irish-Iraqi film curator and writer Róisín Tapponi – also the founder of Shasha Movies, an independent streaming service showcasing Southwest Asian and North African cinema. L’Automne is the third of Hanoun’s four “seasons” and trains its camera on two faces – a film director and an editor in the process of cutting together a film we never see – as they talk movies, art and politics. Hanoun had one foot in the French New Wave but carved a path that was adamantly his own; he slyly pokes fun at the movement’s pretensions as he untangles ideas around how we watch films – and how we watch each other. As Tapponi said after the screening, along with the role that women played in the French New Wave, the sidelined Hanoun is long overdue a reappraisal.

Moi Aussi, Je Regarde by Ingel Vaikla and E for Eileen by Gerard & Kelly

Two films at the festival unearth the stories buried in modernist Cote d’Azur gems: Moi Aussi, Je Regarde focuses on Le Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse in Marseille, his vertical village on stilts that sits between the mountains and the Mediterranean. Ingel Vaikla approaches the architect’s UNESCO-stamped masterpiece (or “house of madmen” to its critics) through its female inhabitants as they skate between its giant stilts and explore its nine “streets” in a riposte to often heavily masculine notions of modernism. Paris-based American artists Gerard & Kelly meanwhile are working on a series of films set amid iconic French architecture.

At the festival they screened their latest, E for Eileen, which draws on the overlooked, subversive life of architect Eileen Gray (played in their film by British actor Nikki Amuka-Bird). Shot entirely at Gray’s ingenious villa E-1027 in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, it’s a fictional take on Gray’s final day there – she mysteriously quit the house in 1932 and never returned – as a raucous crowd of friends and lovers descend on her compact modernist haven. Post-Gray, the house went on to have a strange and chequered history, weathering squatters, murders and Nazis – and defacement by a jealous Le Corbusier, who painted murals across its white walls against Gray’s wishes. Today the villa has been restored to its exquisite 1929 state and the artists’ film makes clear how Gray’s radical-for-the time bisexuality and rejection of society’s rigid confines was reflected in her design. A marvel of foldable tables, pivoting drawers, adjustable lamps and sliding shutters, it’s a fluid and unconventional masterwork perched on a Riviera cliff face.

Find out more about St. Moritz Art Film Festival here.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.