Rewrite

With the sad news of the luminary photographer’s passing, we revisit an interview where Oliviero Toscani discusses the industry as its very own form of reportage, and the terminology of fashion

This article was originally published on 10 March 2016.

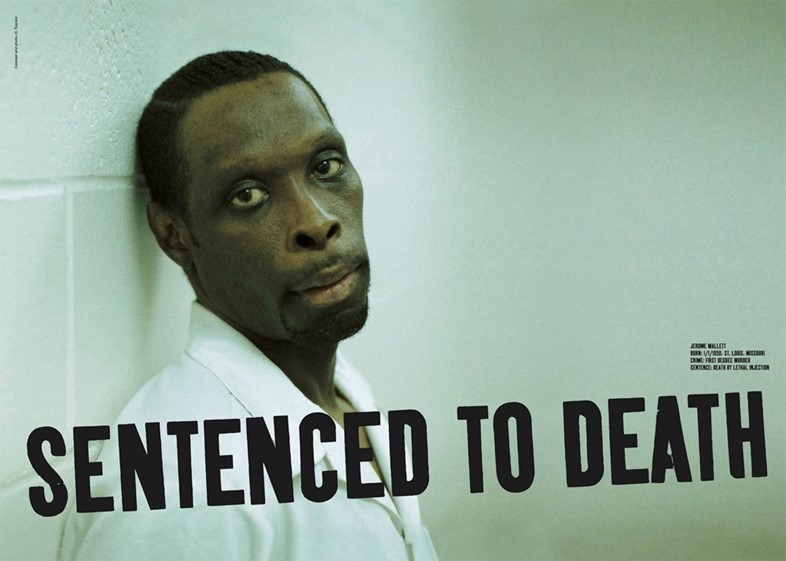

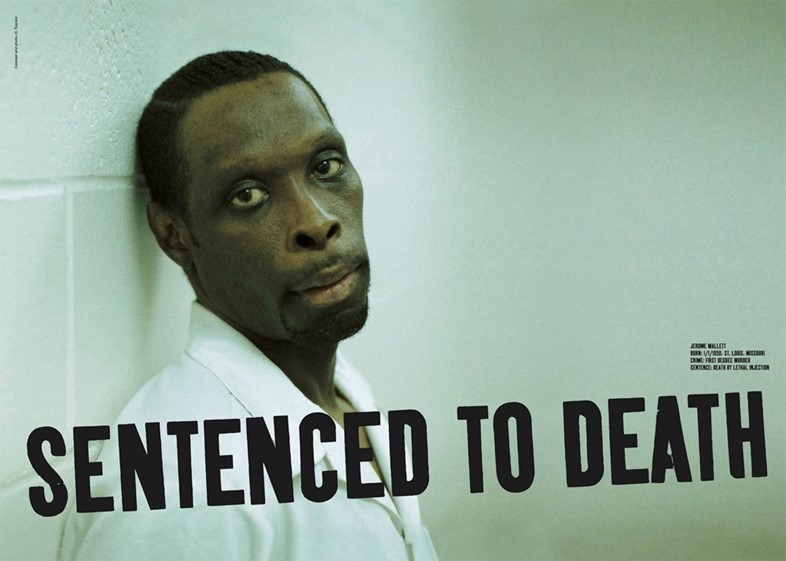

Oliviero Toscani is one of the most famous and celebrated figures working in imagery today. Between 1982 and 2000, he was in charge of the advertisements for Benetton, where he pushed the boundaries of the genre by placing the most shocking imagery imaginable on billboards around the globe, and helped shape the way we have seen photography ever since. He has collaborated with many of the world’s preeminent brands and publications and 2015 saw the publication of Oliviero Toscani: More Than Fifty Years of Magnificent Failures, a book which consolidated many examples of his work throughout his career. Here, he completes our Intellectual Fashion questionnaire, reflecting on the power of his medium and its contextual relevance.

Donatien Grau: How would you connect fashion to elegance?

Oliviero Tosani: Elegance is an independent word, which has nothing to do directly with fashion: there is elegance in fashion, but there is elegance in design, in the way you speak, in the way you walk, in the way you teach. Elegance could be an expression of fashion. Fashion is the fashion that is going on at the moment – and obviously, not everything that is going on at the moment is elegant.

DG: What is the role of history and art history in your conception of fashion?

OT: A naked civilisation has never been civilisation: when human beings started to put a fig leaf on, they started to become a civilisation. We can connect fashion to that moment, in a very primitive way; fashion is one of the expressions of a civilisation. What you wear and what you design is fashion – even architecture, or education. We have to define what “fashion” is. Everything could be fashion: politics could be fashion.

DG: Would you describe fashion as a language and a discourse, as Barthes did?

OT: Fashion is a behaviour; it is also a visual language; a visual social behaviour. We went through different fashions: when I think of politics, slavery used to be fashionable; but it is not like that. The death penalty is fashionable in some countries. These are all systems of representations.

I have been doing fashion photography because I take pictures for magazines which deal with fashion, or mostly clothing, but for me it has never been the most important thing. I was at the Royal College of Art in 1962, when Mary Quant did the mini-skirt, and that was an incredible social action – much more important than a lot of social books written at the time. Thinking that a girl could cut the skirt to make a miniskirt, that was an attitude, a statement of the fact of feminity. To me, that is the real fashion: the development of a social behaviour.

DG: The word “intellectual” was coined in a time of great political distress. Does fashion have a political role? And in which way?

OT: Everything has got a political role. The postcard of Naples with the palm tree, the gulf and the blue sky has got a political meaning. You can make another postcard of Naples in a pile of garbage, and then you have another political vision of the moment there. You have to choose which fashion you belong to: in which part of society you decide to behave, act, and help.

DG: What does fashion have to do with intellectuality?

OT: Of course, it has got to do with intellectuality. Some words always have a positive factor: not everything intellectual is positive, nor intelligent. The word “provocation” has got a negative meaning today; it is an incredible positive word for me. Some words change connotation through time – the same with “intellectual”. Not everything “intellectual” is “intelligent” – it can actually be very stupid. Stupidity is produced by the brain too, eventually. Fashion has got a connotation of superficiality: a superficial product, behaviour. But it is the result of the social, political, physical, cultural evolution; we can focus exactly, through the fashion, on the political moment.

All human expressions go through fashion: they couldn’t have played rock’n’roll in the 18th century, why not? Because they did not know African music and the new instruments. That fashion speaks of the moment. Mozart, Goya and Caravaggio were very fashionable in their time. There are expressions of fashion which really define the historical moment and the social memories.

DG: How would you relate the concept of “fashion” to the one of “style”?

OT: A style could be a fashion moment, a fashion expression. Style is closer to design while fashion is not simply design; it is a final result, while style is the result of technical research.

DG: Fashion is an intrinsic part of contemporary creativity. Where do you place in the broader space of culture?

OT: Anywhere. It is a horizontal expression: Hemingway writes in a certain way, Cioran writes in another way. The fashion is like a technical human result. Today, cars are made in a certain way; that is their fashion; they are much safer, much more reliable, much more consumer-aware. The cars of the 1950s were not like that, but they were much more seductive. Fashion goes with different reasons: they are not always aesthetically or politically the best. But this is the fashion, which defines a limit.

DG: You have conceived some of the most powerful fashion advertisements ever. What is the relation between advertising and the rest of photography produced?

OT: It doesn’t make any difference: anything you publish communicates something and therefore it’s advertising. What was published in Life magazine advertised for the moment to which it belonged. I chose the “advertising media” because thus I could be published with the same picture in all the magazines of the world on the same day. I could not have done that as a reporter for one magazine. I am the son of a photojournalist: my father could only publish in Il Corriere della Sera – that is very limiting somehow.

Producing and consuming are the two major activities of humanity: producing is work and consuming is culture. With the two you can define society: the amount, the form of consumption. In what is called “advertising”, you have the opportunity to be very close to the production and consumption mentality.

One day, archaeologists will pick up our magazines and they will not understand the difference between the advertising and the editorial – or perhaps it will be that they will understand society much better through advertising and use it more. They will pick up Le Monde on November 14, 2015 and on one page they will read what happened in Le Bataclan, then they will find a Chanel advertisement, then an article on the poor treatment of women in some parts of the world, then an advertisement for a Mercedes car. They will wonder what was going on. And that will be how they will engage with our culture. Advertisements are the best reportage of the great movements of society.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

With the sad news of the luminary photographer’s passing, we revisit an interview where Oliviero Toscani discusses the industry as its very own form of reportage, and the terminology of fashion

This article was originally published on 10 March 2016.

Oliviero Toscani is one of the most famous and celebrated figures working in imagery today. Between 1982 and 2000, he was in charge of the advertisements for Benetton, where he pushed the boundaries of the genre by placing the most shocking imagery imaginable on billboards around the globe, and helped shape the way we have seen photography ever since. He has collaborated with many of the world’s preeminent brands and publications and 2015 saw the publication of Oliviero Toscani: More Than Fifty Years of Magnificent Failures, a book which consolidated many examples of his work throughout his career. Here, he completes our Intellectual Fashion questionnaire, reflecting on the power of his medium and its contextual relevance.

Donatien Grau: How would you connect fashion to elegance?

Oliviero Tosani: Elegance is an independent word, which has nothing to do directly with fashion: there is elegance in fashion, but there is elegance in design, in the way you speak, in the way you walk, in the way you teach. Elegance could be an expression of fashion. Fashion is the fashion that is going on at the moment – and obviously, not everything that is going on at the moment is elegant.

DG: What is the role of history and art history in your conception of fashion?

OT: A naked civilisation has never been civilisation: when human beings started to put a fig leaf on, they started to become a civilisation. We can connect fashion to that moment, in a very primitive way; fashion is one of the expressions of a civilisation. What you wear and what you design is fashion – even architecture, or education. We have to define what “fashion” is. Everything could be fashion: politics could be fashion.

DG: Would you describe fashion as a language and a discourse, as Barthes did?

OT: Fashion is a behaviour; it is also a visual language; a visual social behaviour. We went through different fashions: when I think of politics, slavery used to be fashionable; but it is not like that. The death penalty is fashionable in some countries. These are all systems of representations.

I have been doing fashion photography because I take pictures for magazines which deal with fashion, or mostly clothing, but for me it has never been the most important thing. I was at the Royal College of Art in 1962, when Mary Quant did the mini-skirt, and that was an incredible social action – much more important than a lot of social books written at the time. Thinking that a girl could cut the skirt to make a miniskirt, that was an attitude, a statement of the fact of feminity. To me, that is the real fashion: the development of a social behaviour.

DG: The word “intellectual” was coined in a time of great political distress. Does fashion have a political role? And in which way?

OT: Everything has got a political role. The postcard of Naples with the palm tree, the gulf and the blue sky has got a political meaning. You can make another postcard of Naples in a pile of garbage, and then you have another political vision of the moment there. You have to choose which fashion you belong to: in which part of society you decide to behave, act, and help.

DG: What does fashion have to do with intellectuality?

OT: Of course, it has got to do with intellectuality. Some words always have a positive factor: not everything intellectual is positive, nor intelligent. The word “provocation” has got a negative meaning today; it is an incredible positive word for me. Some words change connotation through time – the same with “intellectual”. Not everything “intellectual” is “intelligent” – it can actually be very stupid. Stupidity is produced by the brain too, eventually. Fashion has got a connotation of superficiality: a superficial product, behaviour. But it is the result of the social, political, physical, cultural evolution; we can focus exactly, through the fashion, on the political moment.

All human expressions go through fashion: they couldn’t have played rock’n’roll in the 18th century, why not? Because they did not know African music and the new instruments. That fashion speaks of the moment. Mozart, Goya and Caravaggio were very fashionable in their time. There are expressions of fashion which really define the historical moment and the social memories.

DG: How would you relate the concept of “fashion” to the one of “style”?

OT: A style could be a fashion moment, a fashion expression. Style is closer to design while fashion is not simply design; it is a final result, while style is the result of technical research.

DG: Fashion is an intrinsic part of contemporary creativity. Where do you place in the broader space of culture?

OT: Anywhere. It is a horizontal expression: Hemingway writes in a certain way, Cioran writes in another way. The fashion is like a technical human result. Today, cars are made in a certain way; that is their fashion; they are much safer, much more reliable, much more consumer-aware. The cars of the 1950s were not like that, but they were much more seductive. Fashion goes with different reasons: they are not always aesthetically or politically the best. But this is the fashion, which defines a limit.

DG: You have conceived some of the most powerful fashion advertisements ever. What is the relation between advertising and the rest of photography produced?

OT: It doesn’t make any difference: anything you publish communicates something and therefore it’s advertising. What was published in Life magazine advertised for the moment to which it belonged. I chose the “advertising media” because thus I could be published with the same picture in all the magazines of the world on the same day. I could not have done that as a reporter for one magazine. I am the son of a photojournalist: my father could only publish in Il Corriere della Sera – that is very limiting somehow.

Producing and consuming are the two major activities of humanity: producing is work and consuming is culture. With the two you can define society: the amount, the form of consumption. In what is called “advertising”, you have the opportunity to be very close to the production and consumption mentality.

One day, archaeologists will pick up our magazines and they will not understand the difference between the advertising and the editorial – or perhaps it will be that they will understand society much better through advertising and use it more. They will pick up Le Monde on November 14, 2015 and on one page they will read what happened in Le Bataclan, then they will find a Chanel advertisement, then an article on the poor treatment of women in some parts of the world, then an advertisement for a Mercedes car. They will wonder what was going on. And that will be how they will engage with our culture. Advertisements are the best reportage of the great movements of society.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.