Rewrite

As Luca Guadagnino’s Queer hits cinemas, we trace the visionary writer’s influence on some of cinema’s most celebrated auteurs

Few American writers remain as transgressive as William S Burroughs. The postmodern author’s distinct and daunting literary style makes translating his work for the screen a difficult task, though plenty have tried – and Luca Guadagnino’s adaptation of Burroughs’ early, confessional novella Queer may be the highest profile one yet.

Queer sees heroin-addicted writer William (Daniel Craig) fall hopelessly in lust with Eugene (Drew Starkey), an ex-US serviceman living out in Mexico City. Eugene does not identify as queer and holds William at arm’s length; frustrated, William concocts a paid arrangement whereby Eugene follows him to the jungles of South America, in search of the hallucinogenic drug ayahuasca. En route, the film spirals out into a trippy final act, echoing Burroughs’ own burgeoning literary voice in the novella, characterised by fragmented vignettes and bouts of physiological and psychological anguish.

Perhaps the animating force behind all of Burroughs’ work is a venomous distrust of control – by the body and its needs and by language itself, which operates as a systemised, deliberately imprisoning form of communication. As theorist Ihab Hassan put it, his aim “is to free man by making him bodiless and silencing his language”. It’s a vision encoded into the film’s most daring scene, a psychedelic coupling between William and Eugene that sees their bodies conjoin.

To expand your Burroughs horizons, we’ve curated a guide below to major and obscure highlights of his moving-image adaptations.

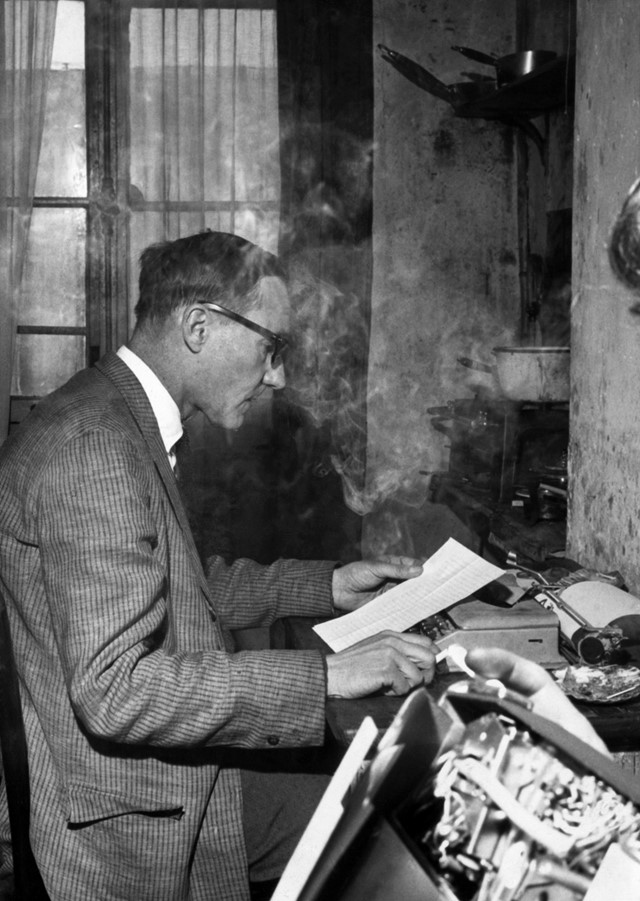

Burroughs was a contested figure even outside of his writing, not least for the accidental killing of his wife, Joan Vollmer, which became the impetus for several books and hung over the short life of his son, William Burroughs, Jr. It’s an extra-textual trauma that finds its way into this 1991 adaptation of Naked Lunch, which is bookended by recreations of its main character, Bill Lee (a delightfully deadpan Peter Weller) shooting his wife and her doppelganger, Joan (Judy Davis). Directed by body-horror auteur David Cronenberg as he was moving away from overtly pulpy fare to more thorny, ambitious and often literary projects, the film turned an uncanny lens on Burroughs’ novel about an expat addict caught up in the geopolitical tensions of the Interzone, an imagined, uncontrollable space. The results are frequently eye-popping, with Cronenberg’s addition of strange, bug-like puppets and fleshy typewriters perfectly capturing the perversion of order and normalcy that is rife in Burroughs’ text.

Read our guide to the films of David Cronenberg here.

There have been multiple attempts to capture William S Burroughs in documentary form – see Pirate Tape – but it’s Howard Brookner’s 1983 thesis project which best reflects the appeal and contradictions of the author’s personality (and has since been blessed with a Criterion Collection release). Brookner, who would die from Aids-related illnesses six years after the film’s premiere, shifts between the candid testimony of Burroughs and his peers (including Allen Ginsberg, Herbert Huncke, Patti Smith and Francis Bacon), insights into the pre-fame days of the Beat generation crew and fittingly lo-fi snapshots of public readings, where Burroughs’ deep, drawling cadence luxuriates on the strangeness of his prose. Notable not just for its scope and fidelity, the doc also captures the discomfort Burroughs’ close circle feels about assessing his volatile family life – scenes of the writer’s dismissive attitude towards his son, who himself would die before the film’s completion, are difficult to stomach.

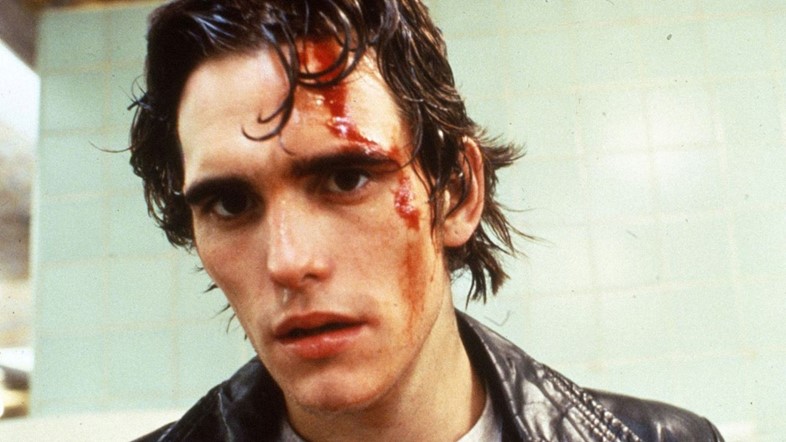

The only film in this guide not to centre Burroughs or his literary work, Gus Van Sant’s admiration for the author (he had previously adapted one of his stories) led him to cast Burroughs in his first Hollywood production. Drugstore Cowboy (1989), about a crew of opioid-addicted pharmacy robbers, is based on the autobiography of James Fogle, himself a drugstore robber who was in and out of prison all his life. Burroughs was offered the role of an older, con-man addict who Bob (Matt Dillon) catches up with when he decides to go straight, but Burroughs asked to make the character a disgraced priest, and rewrote his dialogue with his long-term assistant, James Grauerholz. Burroughs is an excellent addition to the film’s latter stages, a magnetic and playful presence that meshes perfectly with the intoxicating, broody charm of Dillon.

“Boys, school showers and swimming pools full of them.” The voice of William S Burroughs repeats over the industrial pulse of a track by Psychic TV (whose founding member, Genesis P-Orridge, also appears in Decoder), the writer’s words cut up into a non-linear, semi-coherent stream reminiscent of his more experimental prose. This is the soundtrack to Derek Jarman’s Pirate Tape, a short art film shot when Burroughs visited London in 1982. With inconsequential moments in pavements and shop window reflections splintered and slowed down to an unsettling sequence of still images, the film marked Burroughs’ visit by refusing and breaking apart its finite length. A sharp curio rather than a full meal, but Jarman’s aggressive stylistic approach suits Burroughs.

Taking Burroughs’ whole vibe and outlook and applying it to the restless, state-surveilled condition of a latter-stage divided Germany, Decoder (1984) is uncompromising sci-fi from visual artist Mischa that transplants Burroughs’ metaphysical non-fiction work The Electronic Revolution to a new, fictional, political form. In his essays, Burroughs explained how his famous ‘cut-up’ method could disrupt material, political environments through media technology, represented in Decoder by a young punk sound technician (FM Einheit) mixing a tape that causes searing physical pain to listeners. The film fuses punk aesthetics and real footage of Berlin riots with the destabilising texture of tape recordings, and even finds time for a Burroughs cameo amid the sensory chaos.

Lots of Burroughs stories have been adapted into amateur and independent short films, many with the direct participation of Burroughs himself. One of the strangest and most entrancing is this 1993 claymation tale of an addict desperate for a fix on a freezing Christmas, and who sacrifices his bounty for an ailing young man. Animator Nick Donkin and music video director Melodie McDaniel wring out the blackly comic bleakness of the story, which Burroughs narrates with excerpts from his spoken word album Spare Ass Annie. The anti-festive vibe is intensified by sudden rushes of movement and many expressive facial contortions, giving festive new meaning to the concept of going cold turkey. The film is available in lo-res YouTube uploads, where you can find a moving archive of remembrances from recovered addicts, who watch the short as an unofficial seasonal tradition.

Queer is out in UK cinemas on December 13.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

As Luca Guadagnino’s Queer hits cinemas, we trace the visionary writer’s influence on some of cinema’s most celebrated auteurs

Few American writers remain as transgressive as William S Burroughs. The postmodern author’s distinct and daunting literary style makes translating his work for the screen a difficult task, though plenty have tried – and Luca Guadagnino’s adaptation of Burroughs’ early, confessional novella Queer may be the highest profile one yet.

Queer sees heroin-addicted writer William (Daniel Craig) fall hopelessly in lust with Eugene (Drew Starkey), an ex-US serviceman living out in Mexico City. Eugene does not identify as queer and holds William at arm’s length; frustrated, William concocts a paid arrangement whereby Eugene follows him to the jungles of South America, in search of the hallucinogenic drug ayahuasca. En route, the film spirals out into a trippy final act, echoing Burroughs’ own burgeoning literary voice in the novella, characterised by fragmented vignettes and bouts of physiological and psychological anguish.

Perhaps the animating force behind all of Burroughs’ work is a venomous distrust of control – by the body and its needs and by language itself, which operates as a systemised, deliberately imprisoning form of communication. As theorist Ihab Hassan put it, his aim “is to free man by making him bodiless and silencing his language”. It’s a vision encoded into the film’s most daring scene, a psychedelic coupling between William and Eugene that sees their bodies conjoin.

To expand your Burroughs horizons, we’ve curated a guide below to major and obscure highlights of his moving-image adaptations.

Burroughs was a contested figure even outside of his writing, not least for the accidental killing of his wife, Joan Vollmer, which became the impetus for several books and hung over the short life of his son, William Burroughs, Jr. It’s an extra-textual trauma that finds its way into this 1991 adaptation of Naked Lunch, which is bookended by recreations of its main character, Bill Lee (a delightfully deadpan Peter Weller) shooting his wife and her doppelganger, Joan (Judy Davis). Directed by body-horror auteur David Cronenberg as he was moving away from overtly pulpy fare to more thorny, ambitious and often literary projects, the film turned an uncanny lens on Burroughs’ novel about an expat addict caught up in the geopolitical tensions of the Interzone, an imagined, uncontrollable space. The results are frequently eye-popping, with Cronenberg’s addition of strange, bug-like puppets and fleshy typewriters perfectly capturing the perversion of order and normalcy that is rife in Burroughs’ text.

Read our guide to the films of David Cronenberg here.

There have been multiple attempts to capture William S Burroughs in documentary form – see Pirate Tape – but it’s Howard Brookner’s 1983 thesis project which best reflects the appeal and contradictions of the author’s personality (and has since been blessed with a Criterion Collection release). Brookner, who would die from Aids-related illnesses six years after the film’s premiere, shifts between the candid testimony of Burroughs and his peers (including Allen Ginsberg, Herbert Huncke, Patti Smith and Francis Bacon), insights into the pre-fame days of the Beat generation crew and fittingly lo-fi snapshots of public readings, where Burroughs’ deep, drawling cadence luxuriates on the strangeness of his prose. Notable not just for its scope and fidelity, the doc also captures the discomfort Burroughs’ close circle feels about assessing his volatile family life – scenes of the writer’s dismissive attitude towards his son, who himself would die before the film’s completion, are difficult to stomach.

The only film in this guide not to centre Burroughs or his literary work, Gus Van Sant’s admiration for the author (he had previously adapted one of his stories) led him to cast Burroughs in his first Hollywood production. Drugstore Cowboy (1989), about a crew of opioid-addicted pharmacy robbers, is based on the autobiography of James Fogle, himself a drugstore robber who was in and out of prison all his life. Burroughs was offered the role of an older, con-man addict who Bob (Matt Dillon) catches up with when he decides to go straight, but Burroughs asked to make the character a disgraced priest, and rewrote his dialogue with his long-term assistant, James Grauerholz. Burroughs is an excellent addition to the film’s latter stages, a magnetic and playful presence that meshes perfectly with the intoxicating, broody charm of Dillon.

“Boys, school showers and swimming pools full of them.” The voice of William S Burroughs repeats over the industrial pulse of a track by Psychic TV (whose founding member, Genesis P-Orridge, also appears in Decoder), the writer’s words cut up into a non-linear, semi-coherent stream reminiscent of his more experimental prose. This is the soundtrack to Derek Jarman’s Pirate Tape, a short art film shot when Burroughs visited London in 1982. With inconsequential moments in pavements and shop window reflections splintered and slowed down to an unsettling sequence of still images, the film marked Burroughs’ visit by refusing and breaking apart its finite length. A sharp curio rather than a full meal, but Jarman’s aggressive stylistic approach suits Burroughs.

Taking Burroughs’ whole vibe and outlook and applying it to the restless, state-surveilled condition of a latter-stage divided Germany, Decoder (1984) is uncompromising sci-fi from visual artist Mischa that transplants Burroughs’ metaphysical non-fiction work The Electronic Revolution to a new, fictional, political form. In his essays, Burroughs explained how his famous ‘cut-up’ method could disrupt material, political environments through media technology, represented in Decoder by a young punk sound technician (FM Einheit) mixing a tape that causes searing physical pain to listeners. The film fuses punk aesthetics and real footage of Berlin riots with the destabilising texture of tape recordings, and even finds time for a Burroughs cameo amid the sensory chaos.

Lots of Burroughs stories have been adapted into amateur and independent short films, many with the direct participation of Burroughs himself. One of the strangest and most entrancing is this 1993 claymation tale of an addict desperate for a fix on a freezing Christmas, and who sacrifices his bounty for an ailing young man. Animator Nick Donkin and music video director Melodie McDaniel wring out the blackly comic bleakness of the story, which Burroughs narrates with excerpts from his spoken word album Spare Ass Annie. The anti-festive vibe is intensified by sudden rushes of movement and many expressive facial contortions, giving festive new meaning to the concept of going cold turkey. The film is available in lo-res YouTube uploads, where you can find a moving archive of remembrances from recovered addicts, who watch the short as an unofficial seasonal tradition.

Queer is out in UK cinemas on December 13.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.