Rewrite

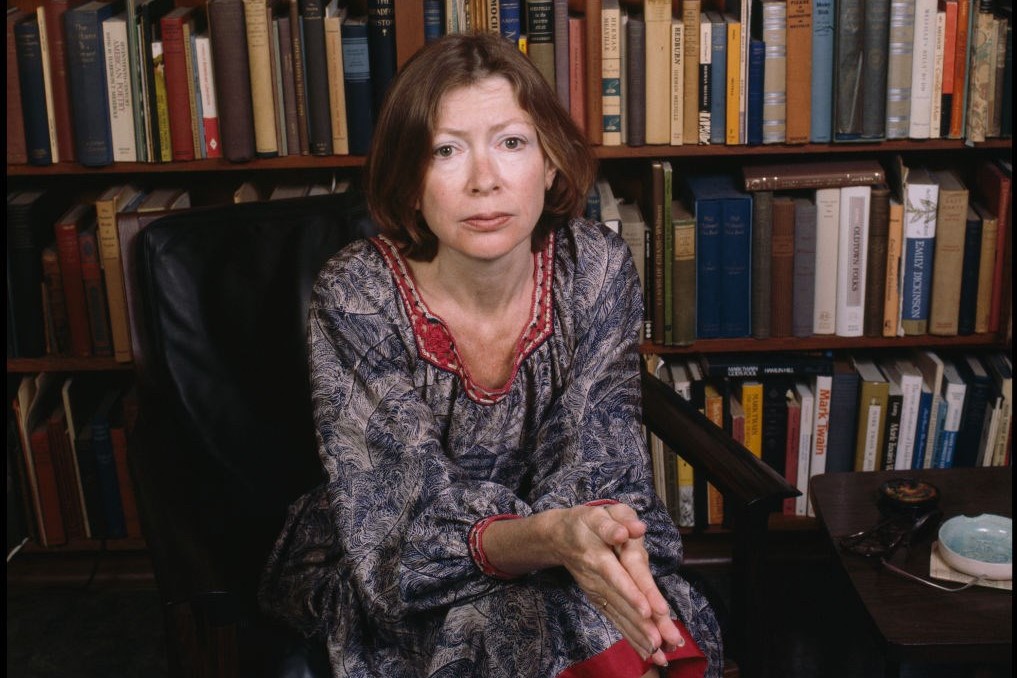

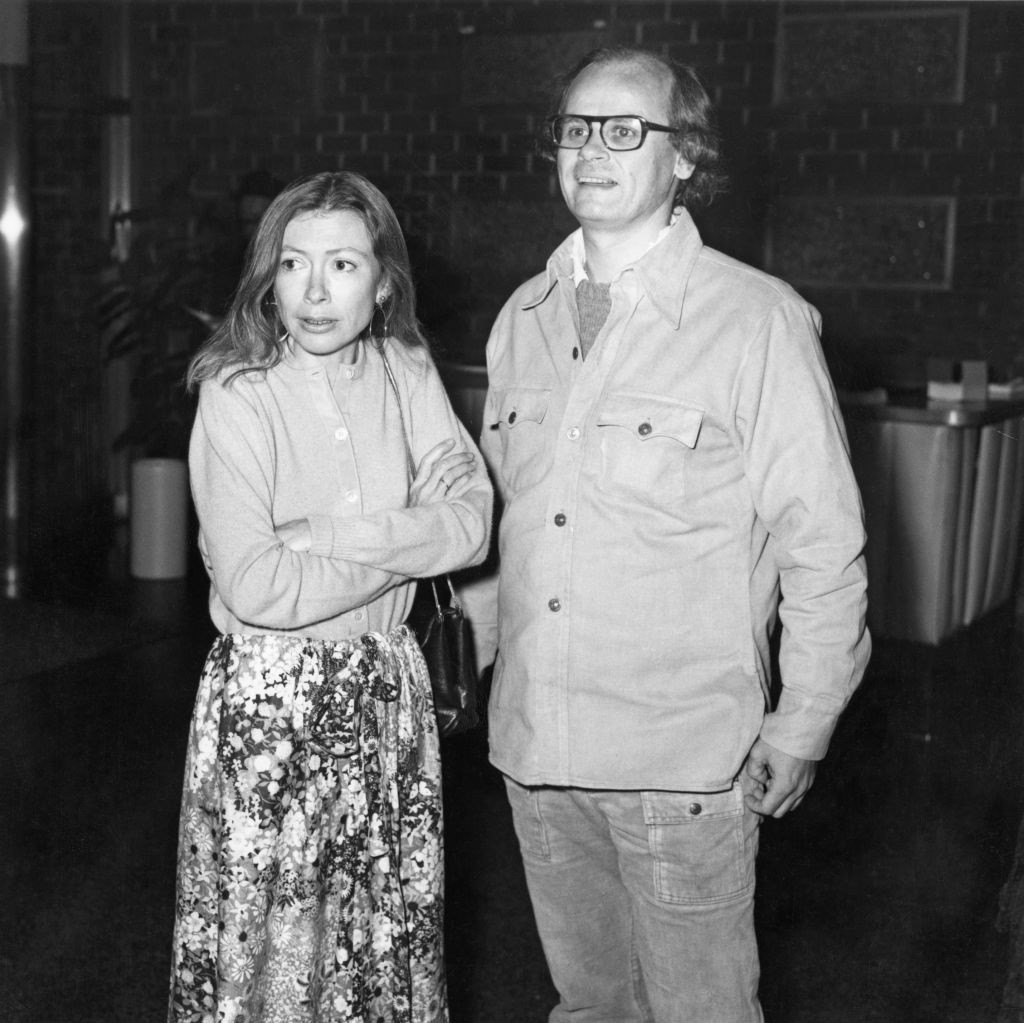

Lead ImageJoan Didion, Berkeley, California, April 1981Photography by Janet Fries. Courtesy of Getty Images

In 2021, journalist Lili Anolik was looking through a box of Eve Babitz’s correspondence – papers which hadn’t come to light when she’d been researching what she’d presumed would be the definitive biography, Hollywood’s Eve (2019). Inside, she discovered an eviscerating letter addressed to Joan Didion, throwing both its writer and intended recipient into a new light. “Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan?” Babitz types, before launching into the denouement of her attack: “It embarrasses me that you don’t read Virginia Woolf. I feel as though you think she’s a ‘woman’s novelist’ … and that you, sharp, accurate journalist, you would never join the ranks of people who sogged around in The Waves. You prefer to be with the boys snickering at the silly women …”

“I pulled that letter out and it’s so electric, such a thrilling document,” Anolik recalls. “And I knew my understanding of Eve was completely imperfect.” With this new knowledge, she intended to revise Hollywood’s Eve, but additional chapters began to accumulate and Didion was becoming an increasingly important figure in the story. “Before I realised it, I was writing a shadow book on Joan,” Anolik explains.

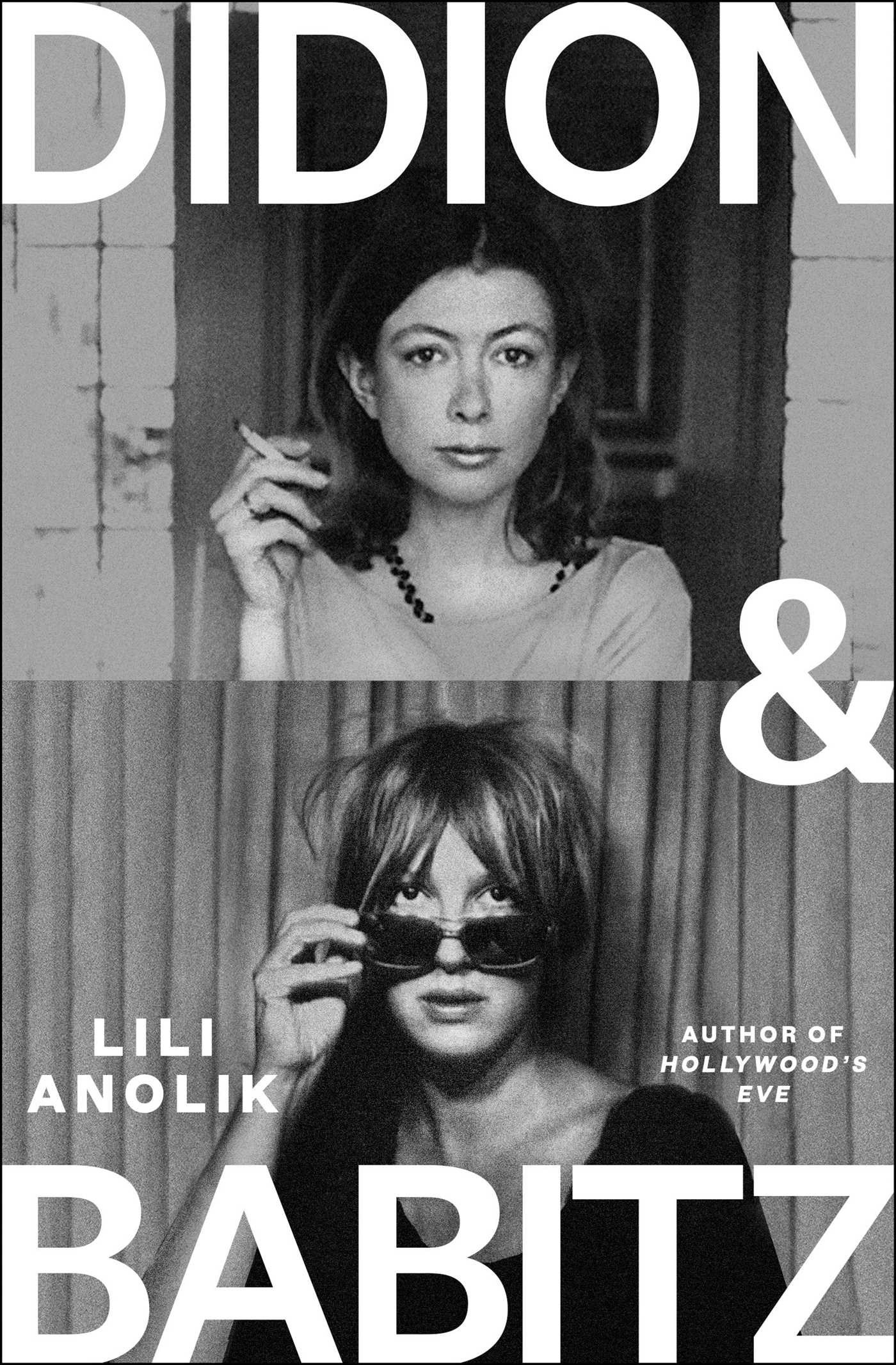

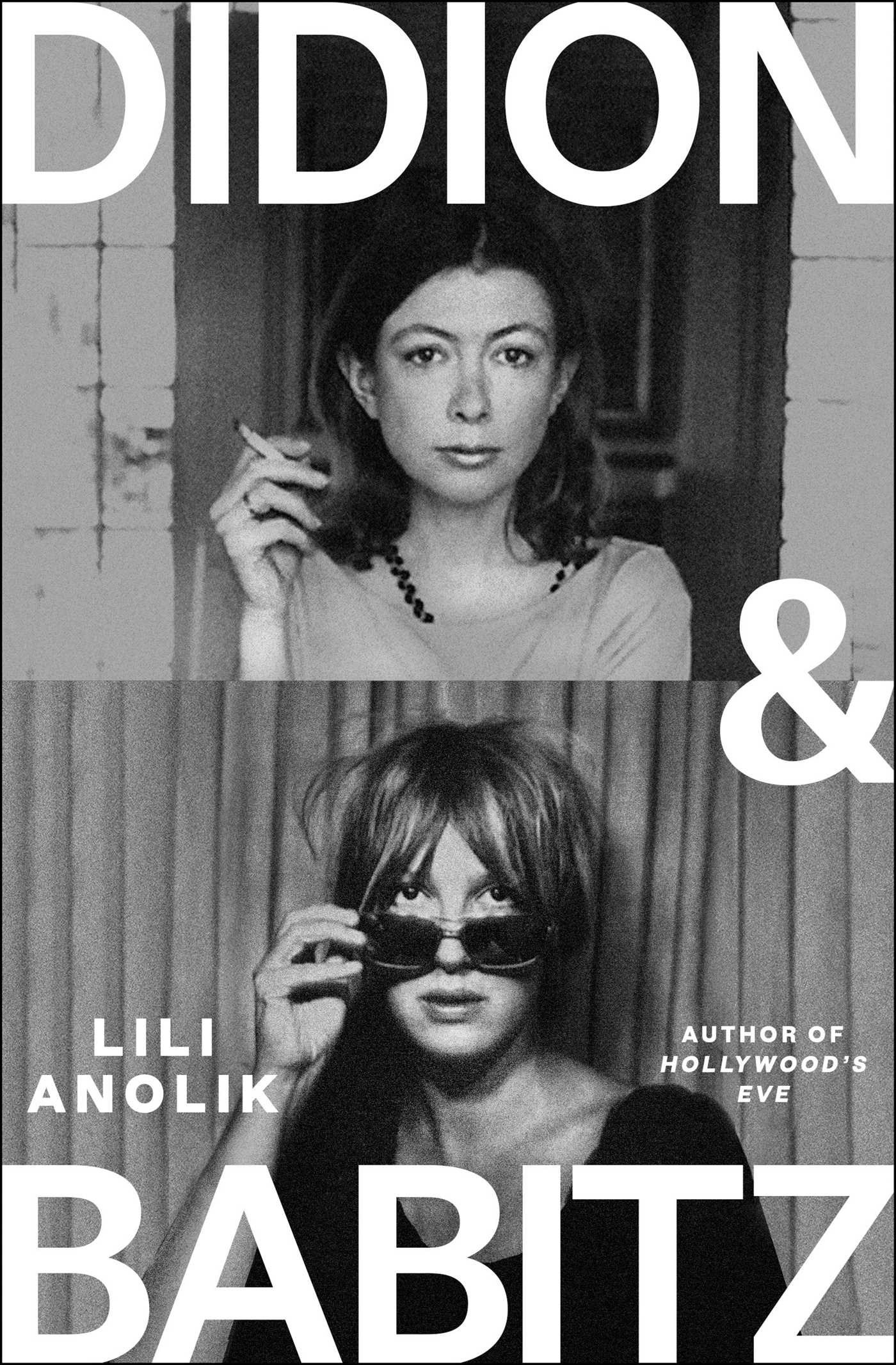

“Shadow book” is the perfect description for what emerged. Didion & Babitz (published by Atlantic) is not so much a dual biography of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz as the story of how their friendship was forged in 1967 and curdled in 1973. It’s also a compelling study of how both writers achieved their status as renowned chroniclers of 60s and 70s counterculture. “They were on the exact same scene at the exact same time, all over each other. The White Album (1979) and Slow Days, Fast Company (1977) both describe this very tiny scene in post-Manson Los Angeles. But then, in other ways, they’re just so opposite,”

Throughout, Anolik builds a riveting and complex case on how these two extraordinary women embodied one another’s shadow selves, examining the light and shade of their psyches; the concealment and exposure of their submerged desires and ambitions.

Below, Lili Anolik talks more about Joan Didion and Eve Babitz.

Emily Dinsdale: Why do you think Eve Babitz and Joan Didion are so frequently held aloft as oppositional figures, like The Beatles and The Stones?

Lili Anolik: We’re attracted to dialectical things, like, you have to pick between Fitzgerald and Hemingway or Britney and Christina Aguilera. But in the case of Joan and Eve, they’re both opposites and twins.

ED: How would you define those qualities that make them distinct from one another? And the traits they share?

LA: I would say they’re unalike in the sense that Joan is a craftsperson. She exerts control. You can see it in her body … tight, trim, control, control, control. And then you get Eve, who fucks and eats and is emotionally sloppy but there’s an authenticity to her. They’re opposites in those ways.

But where they are exactly alike is their total commitment to writing. To be a great writer was probably the most important thing to both of them. I think that they were artists before they were people which, I guess, in a human sense, is maybe alarming, but to me, it’s kind of admirable and thrilling. They go all the way.

ED: I love both of their writing, but I’d prefer to sit next to Eve at a dinner party.

LA: Joan didn’t talk much at parties. I remember Bret [Easton Ellis] telling me about parties at her house, how she’d hand you a drink and then not say anything. He said it was terrifying. So I think your instincts bear out.

ED: Would you say they’re perfect foils to one another?

LA: They’re like foils, but they’re also identical. I always go back to how, when Joan describes herself in her work, she’s always really describing Eve. She wrote that great piece On Self-Respect, and, approvingly, she quotes Rhett Butler from Gone With the Wind, “With enough courage, you can do without a reputation”, which is absolutely how Eve lived her life, right? ‘Eve Bah-bitz, with the great big tits’, called herself a groupie, [she] didn’t care. It does take a weird kind of nerve or stupidity to make your life so much harder. Whereas Joan cultivated and obsessed over her reputation. I always felt Eve didn’t catch on in her time because she wasn’t shrewd about constructing a persona like Joan was.

“Joan cultivated and obsessed over her reputation. I always felt Eve didn’t catch on in her time because she wasn’t shrewd about constructing a persona like Joan was” – Lili Anolik

ED: But I think they’re both self-mythologising in their ways …

LA: Joan wanted to be the cat who walked alone. So she writes Noel Parmentel [her first and, arguably, only big love affair] out of her origin story. That could have been because it was painful for her. But it was through his hustle that her first book gets published. He’s an enormously important figure to her early on and she never mentions him. And she doesn’t mention things like the rave review in the New York Times on Slouching Towards Bethlehem, written by Dan Wakefield – one of her closest friends – who’ll later become Eve’s boyfriend. She cuts those things out. She has a need to control her story, as if she’s such a gargantuan talent that she rose to the top naturally. I mean, she is a gargantuan talent, but she had help.

And Eve absolutely cut Joan out of her origin story. She admitted Joan was helpful to her getting into Rolling Stone, but she never says that Joan edited Eve’s Hollywood [her debut book]. Eve basically traded on Joan’s reputation to get the book bought and that’s a huge reason it got published in the first place. I think falling out with Joan was a source of pain and her dependence on Joan was a source of pain for her too, so she edited that out as well.

ED: The unsent letter you discovered from Eve to Joan is so unsparingly cutting. It shocked me. What does it reveal about why or how their relationship soured?

LA: It’s harsh. She’s calling Joan Didion a sellout; she felt Joan sold out women, she felt that Joan pandered. There’s something dark, ambiguous, knotty, female, and messy that Eve associated with being a woman and also being an artist. Whereas Joan wanted to be the one girl let into the boys’ club.

Joan would pick Hemingway as her model, versus Eve picking Marilyn Monroe. Monroe had such a hard time and so many people didn’t take her seriously, but she’s one of the only cultural figures from the 20th century who has survived. Joan picks Hemingway, who writes on totally masculine topics, his sentences are short and butch. I mean, when you examine Hemingway, he’s actually much more complicated. His sexuality is more complicated and his masculine/feminine qualities are much more complicated. Also, he and Marilyn Monroe will end the same way, with suicides or overdoses. But, broadly, Joan picked masculine models … she will not read Virginia Woolf, she will read Hemingway.

Nowadays, Eve Babitz is up there on the Mount Rushmore of women writers and important California writers. But when I began researching her for Vanity Fair [circa 2012] half the people I approached for interviews just thought of Eve as a bimbo, a girl who fucked around town, a drug person, kind of a screw-up. Now, it’s completely different because the culture has validated her. But I still have pangs when I’m reading Eve’s letters and journals where I think she’s doing something stupid, like, don’t fuck that guy, they’re only looking for a chance to dismiss you.

Joan never conducts herself that way. And Joan had a much easier career because the world’s not a perfect place and people aren’t that smart, so why make it so easy for them to dismiss you? Eve wasn’t playing the game like Joan did, to her credit but also to her detriment.

ED: Joan Didion is a revered figure but doesn’t always come out of the book well. Do you think readers might be surprised or even annoyed by your portrayal of her?

LA: I’m already stealing myself for that kind of reaction because people take her so personally. I would struggle to think of another American writer who has fascinated, beguiled, and imposed themselves on the American consciousness for such an extended time … maybe only Hemingway is her only equal in those terms, or Fitzgerald. So I guess I’m just trying to show how she did it … the psychic arrangements she made, the marriage she made, the sacrifices she made, the coldness, the commitment, the things she didn’t want to show.

“In a way, this book is about how Joan [Didion] became the biggest American writer” – Lili Anolik

Her only two books don’t respect – though I respect them as shrewd commercial decisions, but I regard them as dishonest books – are those last two memoirs, The Year of Magical Thinking (2003) and Blue Nights (2011). I feel like at that point, she sensed that the world wanted to sentimentalise her, and she got on board with that. I don‘t think they were honest portraits of her marriage, or of her as a parent.

In a way, this book is about about how Joan became the biggest American writer. And, of course, it involves operating and hustling and manoeuvring and some things that are attractive qualities. But, to me, that’s what makes her so exciting. She did it, she pulled it off, and it’s great. Personally, I love her ambition and I love her ruthlessness. I find that very appealing.

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik is published by Atlantic Books, and is out now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageJoan Didion, Berkeley, California, April 1981Photography by Janet Fries. Courtesy of Getty Images

In 2021, journalist Lili Anolik was looking through a box of Eve Babitz’s correspondence – papers which hadn’t come to light when she’d been researching what she’d presumed would be the definitive biography, Hollywood’s Eve (2019). Inside, she discovered an eviscerating letter addressed to Joan Didion, throwing both its writer and intended recipient into a new light. “Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan?” Babitz types, before launching into the denouement of her attack: “It embarrasses me that you don’t read Virginia Woolf. I feel as though you think she’s a ‘woman’s novelist’ … and that you, sharp, accurate journalist, you would never join the ranks of people who sogged around in The Waves. You prefer to be with the boys snickering at the silly women …”

“I pulled that letter out and it’s so electric, such a thrilling document,” Anolik recalls. “And I knew my understanding of Eve was completely imperfect.” With this new knowledge, she intended to revise Hollywood’s Eve, but additional chapters began to accumulate and Didion was becoming an increasingly important figure in the story. “Before I realised it, I was writing a shadow book on Joan,” Anolik explains.

“Shadow book” is the perfect description for what emerged. Didion & Babitz (published by Atlantic) is not so much a dual biography of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz as the story of how their friendship was forged in 1967 and curdled in 1973. It’s also a compelling study of how both writers achieved their status as renowned chroniclers of 60s and 70s counterculture. “They were on the exact same scene at the exact same time, all over each other. The White Album (1979) and Slow Days, Fast Company (1977) both describe this very tiny scene in post-Manson Los Angeles. But then, in other ways, they’re just so opposite,”

Throughout, Anolik builds a riveting and complex case on how these two extraordinary women embodied one another’s shadow selves, examining the light and shade of their psyches; the concealment and exposure of their submerged desires and ambitions.

Below, Lili Anolik talks more about Joan Didion and Eve Babitz.

Emily Dinsdale: Why do you think Eve Babitz and Joan Didion are so frequently held aloft as oppositional figures, like The Beatles and The Stones?

Lili Anolik: We’re attracted to dialectical things, like, you have to pick between Fitzgerald and Hemingway or Britney and Christina Aguilera. But in the case of Joan and Eve, they’re both opposites and twins.

ED: How would you define those qualities that make them distinct from one another? And the traits they share?

LA: I would say they’re unalike in the sense that Joan is a craftsperson. She exerts control. You can see it in her body … tight, trim, control, control, control. And then you get Eve, who fucks and eats and is emotionally sloppy but there’s an authenticity to her. They’re opposites in those ways.

But where they are exactly alike is their total commitment to writing. To be a great writer was probably the most important thing to both of them. I think that they were artists before they were people which, I guess, in a human sense, is maybe alarming, but to me, it’s kind of admirable and thrilling. They go all the way.

ED: I love both of their writing, but I’d prefer to sit next to Eve at a dinner party.

LA: Joan didn’t talk much at parties. I remember Bret [Easton Ellis] telling me about parties at her house, how she’d hand you a drink and then not say anything. He said it was terrifying. So I think your instincts bear out.

ED: Would you say they’re perfect foils to one another?

LA: They’re like foils, but they’re also identical. I always go back to how, when Joan describes herself in her work, she’s always really describing Eve. She wrote that great piece On Self-Respect, and, approvingly, she quotes Rhett Butler from Gone With the Wind, “With enough courage, you can do without a reputation”, which is absolutely how Eve lived her life, right? ‘Eve Bah-bitz, with the great big tits’, called herself a groupie, [she] didn’t care. It does take a weird kind of nerve or stupidity to make your life so much harder. Whereas Joan cultivated and obsessed over her reputation. I always felt Eve didn’t catch on in her time because she wasn’t shrewd about constructing a persona like Joan was.

“Joan cultivated and obsessed over her reputation. I always felt Eve didn’t catch on in her time because she wasn’t shrewd about constructing a persona like Joan was” – Lili Anolik

ED: But I think they’re both self-mythologising in their ways …

LA: Joan wanted to be the cat who walked alone. So she writes Noel Parmentel [her first and, arguably, only big love affair] out of her origin story. That could have been because it was painful for her. But it was through his hustle that her first book gets published. He’s an enormously important figure to her early on and she never mentions him. And she doesn’t mention things like the rave review in the New York Times on Slouching Towards Bethlehem, written by Dan Wakefield – one of her closest friends – who’ll later become Eve’s boyfriend. She cuts those things out. She has a need to control her story, as if she’s such a gargantuan talent that she rose to the top naturally. I mean, she is a gargantuan talent, but she had help.

And Eve absolutely cut Joan out of her origin story. She admitted Joan was helpful to her getting into Rolling Stone, but she never says that Joan edited Eve’s Hollywood [her debut book]. Eve basically traded on Joan’s reputation to get the book bought and that’s a huge reason it got published in the first place. I think falling out with Joan was a source of pain and her dependence on Joan was a source of pain for her too, so she edited that out as well.

ED: The unsent letter you discovered from Eve to Joan is so unsparingly cutting. It shocked me. What does it reveal about why or how their relationship soured?

LA: It’s harsh. She’s calling Joan Didion a sellout; she felt Joan sold out women, she felt that Joan pandered. There’s something dark, ambiguous, knotty, female, and messy that Eve associated with being a woman and also being an artist. Whereas Joan wanted to be the one girl let into the boys’ club.

Joan would pick Hemingway as her model, versus Eve picking Marilyn Monroe. Monroe had such a hard time and so many people didn’t take her seriously, but she’s one of the only cultural figures from the 20th century who has survived. Joan picks Hemingway, who writes on totally masculine topics, his sentences are short and butch. I mean, when you examine Hemingway, he’s actually much more complicated. His sexuality is more complicated and his masculine/feminine qualities are much more complicated. Also, he and Marilyn Monroe will end the same way, with suicides or overdoses. But, broadly, Joan picked masculine models … she will not read Virginia Woolf, she will read Hemingway.

Nowadays, Eve Babitz is up there on the Mount Rushmore of women writers and important California writers. But when I began researching her for Vanity Fair [circa 2012] half the people I approached for interviews just thought of Eve as a bimbo, a girl who fucked around town, a drug person, kind of a screw-up. Now, it’s completely different because the culture has validated her. But I still have pangs when I’m reading Eve’s letters and journals where I think she’s doing something stupid, like, don’t fuck that guy, they’re only looking for a chance to dismiss you.

Joan never conducts herself that way. And Joan had a much easier career because the world’s not a perfect place and people aren’t that smart, so why make it so easy for them to dismiss you? Eve wasn’t playing the game like Joan did, to her credit but also to her detriment.

ED: Joan Didion is a revered figure but doesn’t always come out of the book well. Do you think readers might be surprised or even annoyed by your portrayal of her?

LA: I’m already stealing myself for that kind of reaction because people take her so personally. I would struggle to think of another American writer who has fascinated, beguiled, and imposed themselves on the American consciousness for such an extended time … maybe only Hemingway is her only equal in those terms, or Fitzgerald. So I guess I’m just trying to show how she did it … the psychic arrangements she made, the marriage she made, the sacrifices she made, the coldness, the commitment, the things she didn’t want to show.

“In a way, this book is about how Joan [Didion] became the biggest American writer” – Lili Anolik

Her only two books don’t respect – though I respect them as shrewd commercial decisions, but I regard them as dishonest books – are those last two memoirs, The Year of Magical Thinking (2003) and Blue Nights (2011). I feel like at that point, she sensed that the world wanted to sentimentalise her, and she got on board with that. I don‘t think they were honest portraits of her marriage, or of her as a parent.

In a way, this book is about about how Joan became the biggest American writer. And, of course, it involves operating and hustling and manoeuvring and some things that are attractive qualities. But, to me, that’s what makes her so exciting. She did it, she pulled it off, and it’s great. Personally, I love her ambition and I love her ruthlessness. I find that very appealing.

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik is published by Atlantic Books, and is out now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.