Rewrite

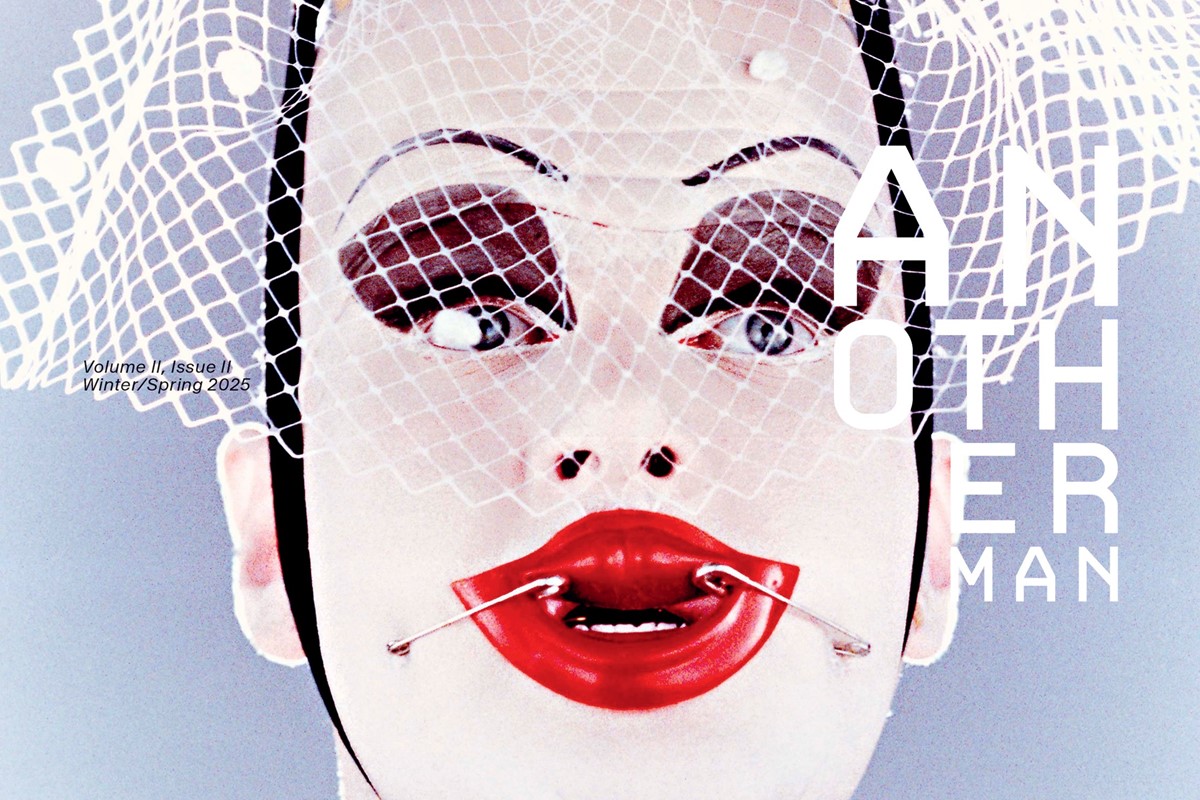

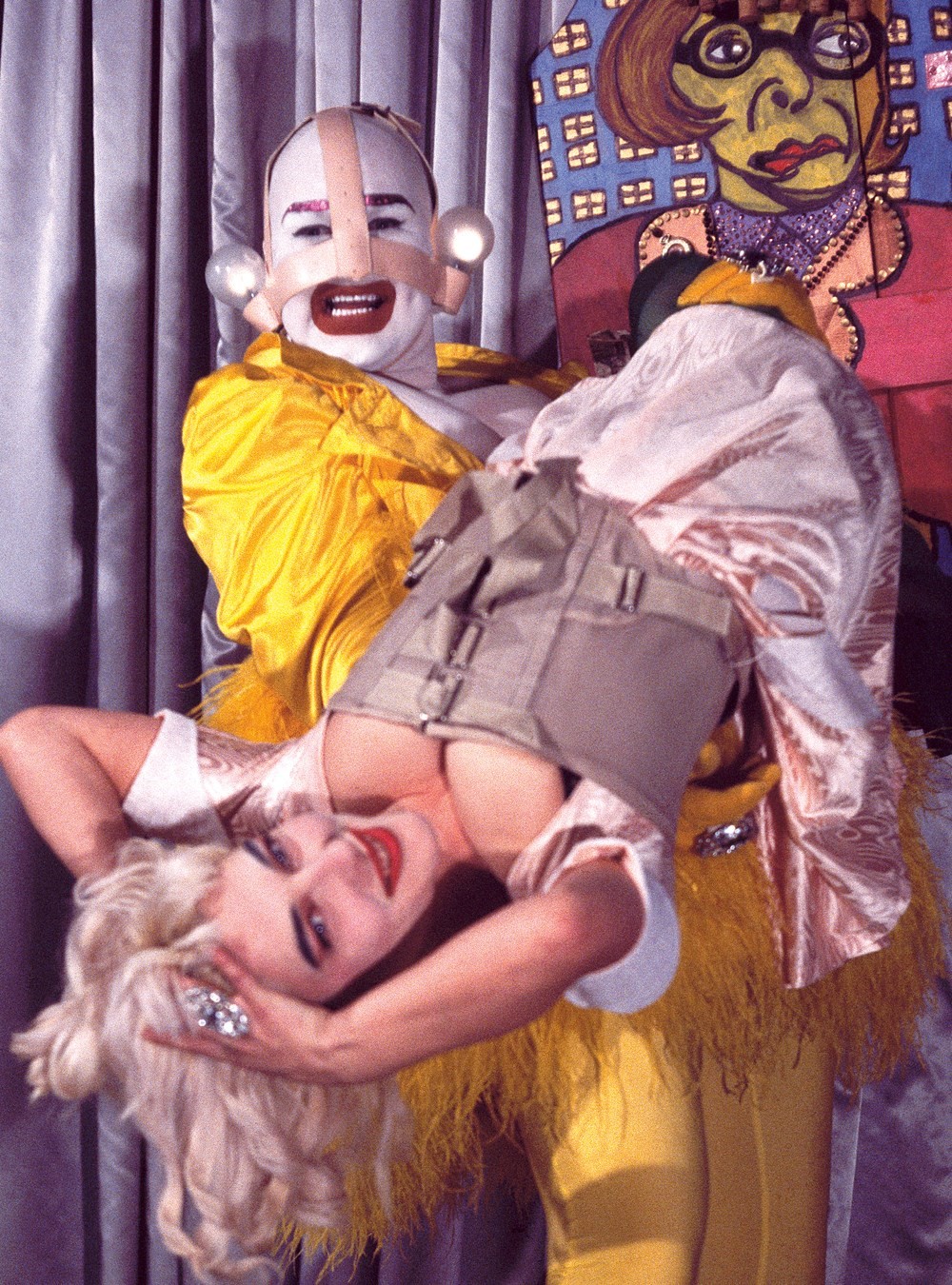

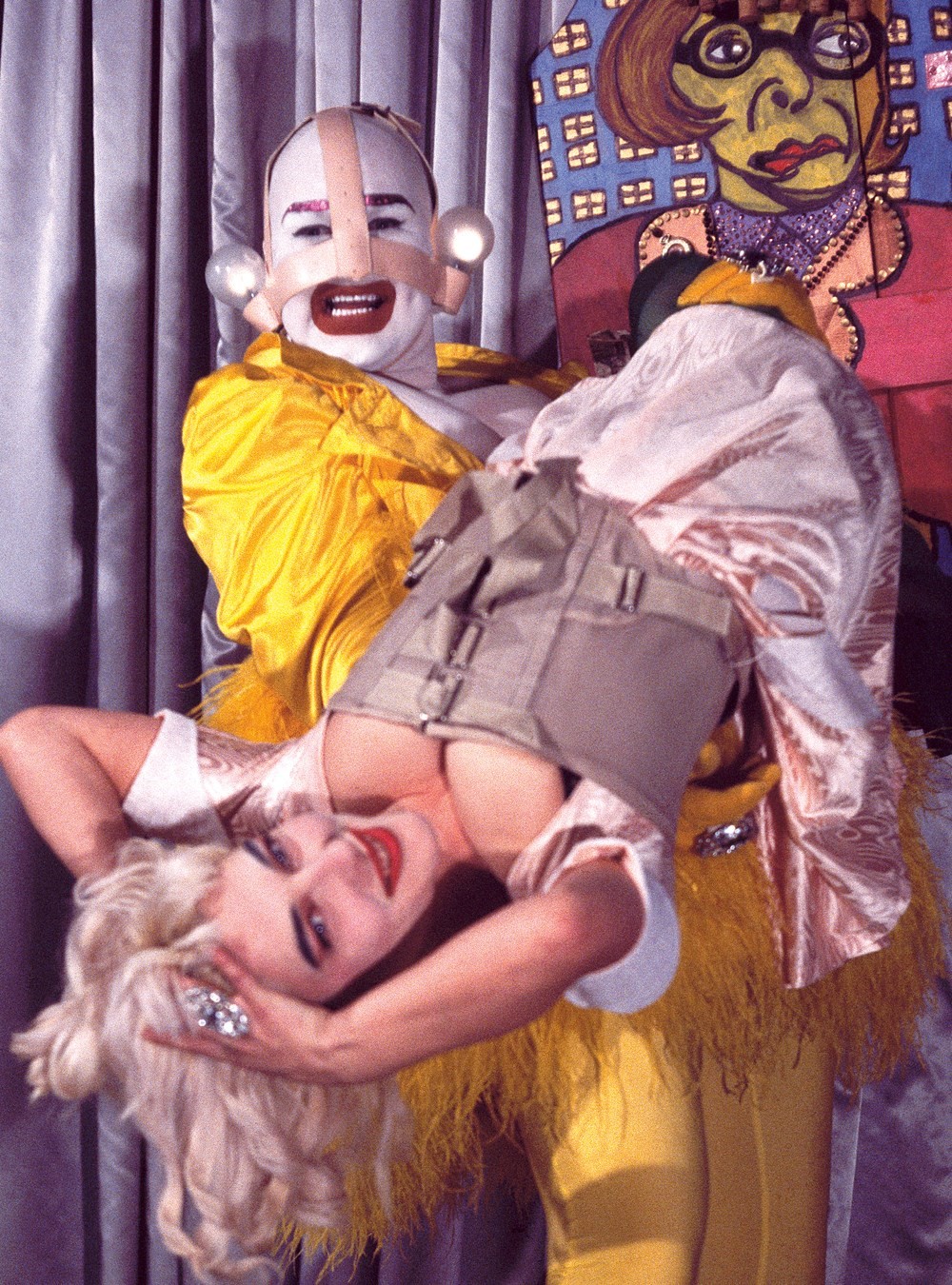

Lead ImageLeigh Bowery, 1992Photography by Nick Knight

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally now:

“Singing and dancing, man expresses himself as a member of a higher community: he has forgotten how to walk and talk, and is about to fly dancing into the heavens. His gestures express enchantment. Just as the animals now speak, and the earth yields up milk and honey, he now gives voice to supernatural sounds: he feels like a god, he himself now walks about enraptured and elated as he saw the gods walk in dreams. Man is no longer an artist, he has become a work of art.” Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

“Nightclubs!” exclaimed the late Judy Blame. “I think everyone has to go to nightclubs to learn about anything. It’s true! I think nightclubs are more important than school really. For certain people, not everyone – some people fall victim to it. But for some, they’re more important than school. I wouldn’t have met Leigh Bowery if it hadn’t been for nightclubs.”

Judy Blame said this 15 years ago and Michael Clark confirms it today, “It was Mother Blame that took Leigh under his wing – it was when Leigh worked in Burger King.” He says, sat on a lime green banquette in a Gloucester Road hotel. That makes it sound like one of his sets, it isn’t. That seat is suburban and pedestrian, something the dancer, choreographer and impresario Michael Clark will never be.

15 years ago, Judy Blame’s tale of Leigh continued: “When he first came here, he was a funny little thing, wearing horrible, long, brown monk coats. I was working on the door of a nightclub with my friend Scarlett; we said, ‘he looks interesting, get him in.’ We were shameless, there were more people stood outside Cha-Chas than inside – we were a bit choosey. Leigh said – he was green of course, still working in Burger King, just from Australia – ‘If you hadn’t let me into that club … You changed my life.’ And what he did in nightclubs was to become British haute couture with an Australian twang.”

The irrepressible spirit, provocation and talent of Judy Blame and that of his one-time monk-coated mentee Leigh Bowery, are much missed. This is the first time that Michael Clark has openly spoken about Leigh Bowery since his death 30 years ago. Since 1994, this hole in his life has been something too painful, weird and plain incomprehensible for him to contemplate. As he put it in text messages before our meeting: “I read something earlier about George Balanchine reacting to the death of Aldous Huxley. He was so shocked and upset he couldn’t put it into words … I think I have been like that about Leigh for a long time … I am thrilled he is going to be celebrated by Tate Modern. God … I miss him.”

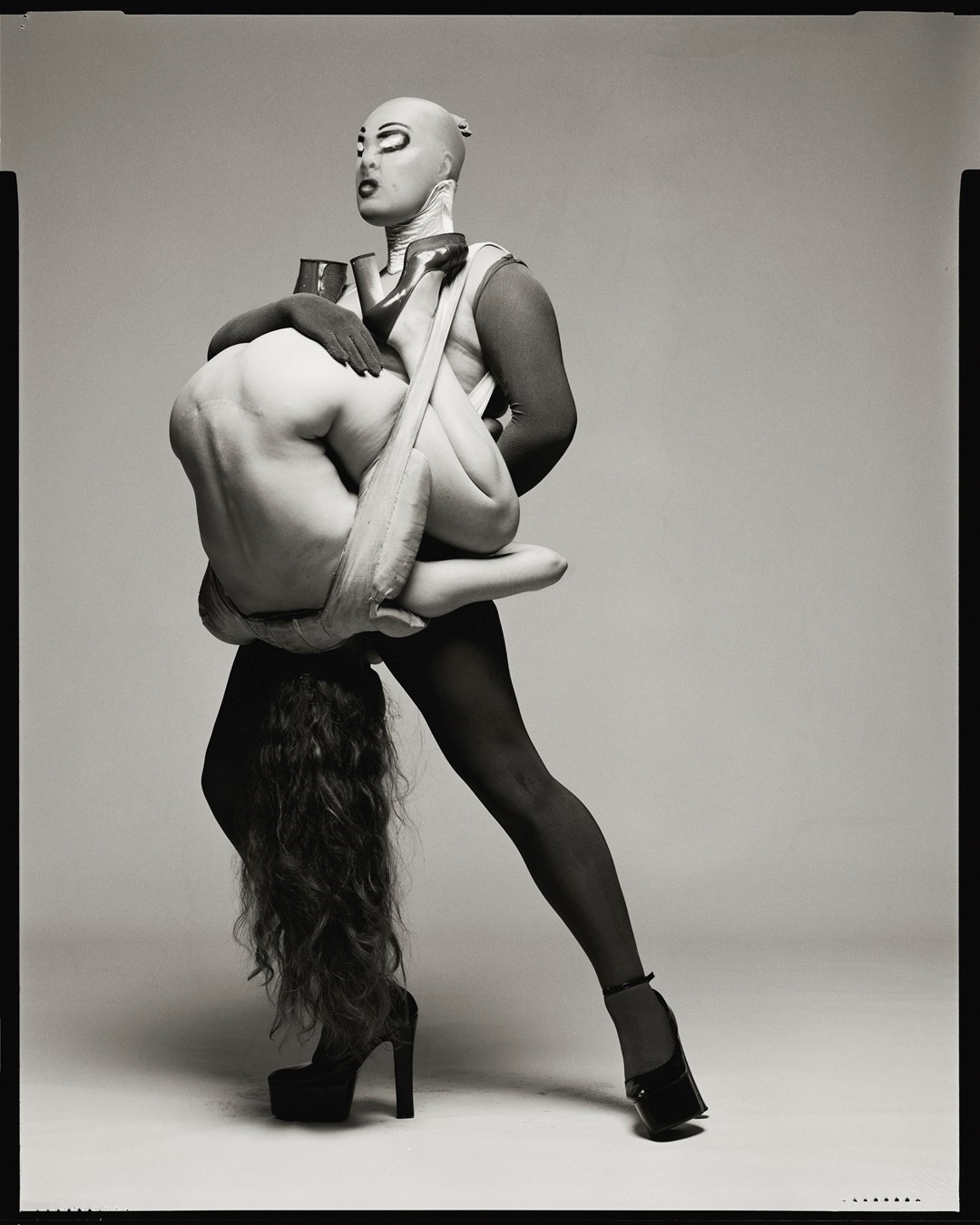

With the approaching Tate retrospective, will the final process in the canonisation of Leigh Bowery be complete? Blessed and beatified, is Leigh Bowery about to gain some sort of sainthood in the Turbine Hall? Bowery was bigger than life when he was alive, both literally and figuratively – six foot three and always in heels, “Leigh thought you could never be too tall,” confirms Clark. Yet since his death, he has gained a further symbolism. He stands for a notion of unbridled creativity and experimentation performed largely on himself – done without establishment approval, without commercial backing, without brand ambassadorships, metric measurements and all that clap-trap of our contemporary existence. Instead, he was a world unto himself, a walking work of art and a catalyst for so many of the people who were close to him or even experienced the sight of him. If we’re being all Nietzschean about it, he was a walking, talking personification of the Dionysian, found on the dancefloor of Taboo or Terpsichorean as a teapot in a Clark-choreographed ballet; giving birth to his wife Nicola onstage or in full-blown muse mode modelling for the painter Lucian Freud. Yet he was also something very real, funny, smart, poignant and human to his friends; he was someone rather than something.

“Mark said something,” says Michael Clark of the late Mark E Smith. “‘My friends don’t amount to one hand / there are 12 people in the world, the rest are paste.’ When Leigh died, I lost one of those people, then with Mark, the same.”

“I read something earlier about George Balanchine reacting to the death of Aldous Huxley. He was so shocked and upset he couldn’t put it into words … I think I have been like that about Leigh for a long time“ – Michael Clark

Mark E Smith, frontman and driving force of The Fall, radical proponent of the English language as a lyricist and a profound working partner for both Michael Clark and Leigh Bowery; it is safe to say, he didn’t suffer fools gladly and gave dilettantes short shrift. He was not only a friend but also a catalyst for Clark, just as Leigh Bowery was. They were both exponents of and believers in the devotion and rigour it takes to make new work: “Mark responded to that. He could see how hard we worked. He was really impressed. I think he said to the band, ‘Michael’s like us. He’s really just trying to do good work, and he’s working really hard.’ And he was like that too.”

Clark continues: “Leigh was incredible. I was reminding myself of my intention when I started making work. Everyone had stripped everything down. Costumes were not costumes they were street clothes. The dance was meant to be the interesting thing. But for some of us, our only means of expression to show how we felt about the world was how we dressed. You could show how angry you were, for example. I wanted to bring people together who are equally strong. I mean, what I learned is to let people do exactly what they want to do. You can’t really tell people what to do and get the best out of them, so let them do what they’re interested in.”

In this way – and more – Leigh Bowery became an essential part of the expression of Michael Clark’s ‘YES Manifesto’, written in 1984 in response to American dancer and choreographer Yvonne Rainer’s ‘NO Manifesto.’

Yes to spectacle.

Yes to virtuosity.

Yes to transformations and magic and make-believe.

Yes to the glamour and transcendency of the star image.

Yes to the heroic.

Yes to the anti-heroic.

Yes to trash imagery.

Yes to the involvement of the performer or spectator.

Yes to style.

Yes to camp.

Yes to seduction by the wiles of the performer.

Yes to eccentricity.

Yes to moving or being moved.

“With Leigh, the first thing we did was actually very conventional,” explains Clark. “It was a narrative of Echo and Narcissus. He came into rehearsal, and I told him, ‘She’s Echo and he’s Narcissus.’ But then how he was dressing himself, with Trojan and David – it’s what we called ‘The Three Kings’ – it was platform shoes, face and body paint, it was quite god-like in a way. That’s how he looked when I first met him. I’d seen him in Jeremy Healy’s club, Circus. I went to the toilet, where he was hanging out with Trojan and David, and asked him if he would do costumes for me. I then had to meet him in the daytime for the first time, and he was in a totally straight look with obviously something odd about it. He was very quiet, but so polite in those days, even later on he was very polite. He sat in the corner and I don’t know what he was thinking.”

Of course, as time went on their relationship in work and life became inseparable. “Leigh educated me as much as I did him,” says Clark of their connection. “I remember him taking me around a de Kooning exhibition in Amsterdam, and it meant nothing to me. He was trying to convey to me how it worked for him and what he thought it was about. He was very patient – he also did the same with my work. He made me aware of how, when I thought dance was just pretentious nonsense, it meant something. Sometimes I’d fall asleep, I’d wake up with my own work on a video, on the TV screen and I’d think ‘What the fuck is this? This is ridiculous,’ then I’d realise it was actually my work. So, I’ve always had a bit of perspective on dance, but Leigh would remind me of the worth. He was, I guess, a kind of objective eye. He was in rehearsals and would make me aware of how good what I was doing was. He was very good at bringing everyone together. That was his kind of attitude, he’d say ‘Somebody’s got to do it, if we don’t do it what is there?’ That was his attitude.”

Leigh Bowery’s specialness, his attitude, his humour and star quality led to him being part of the performance as well as one of the costume designers. “I wanted him around,” explains Clark. “At that time, if I was fond of somebody, I just got them in the company and then they would become part of the performance. I mean, a lot of critics kind of accused me of just thinking my life was so interesting I’d put it on stage and that was enough. That wasn’t really what I was doing. Although the only element of that might have been this wanting to embrace my mum and Leigh.”

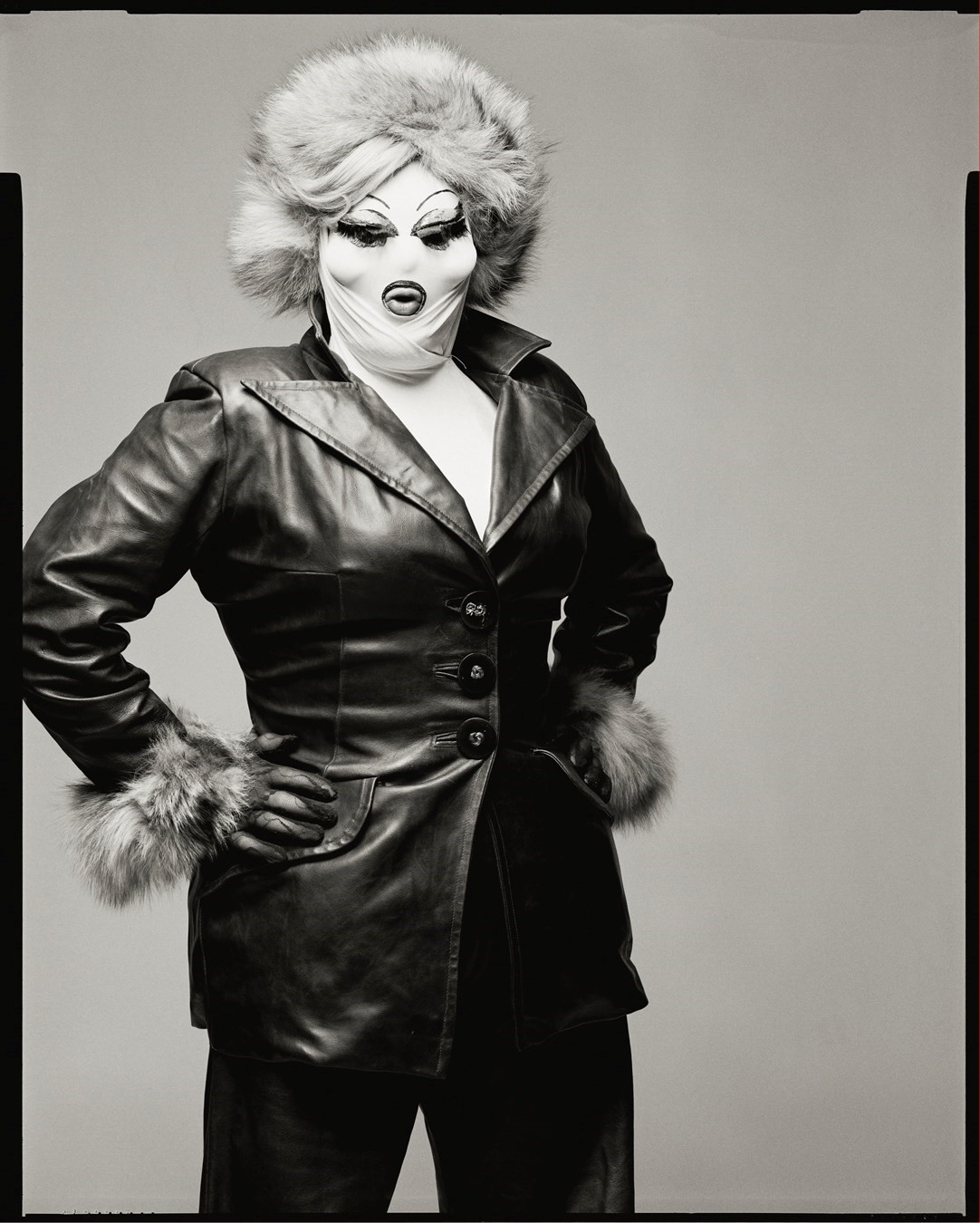

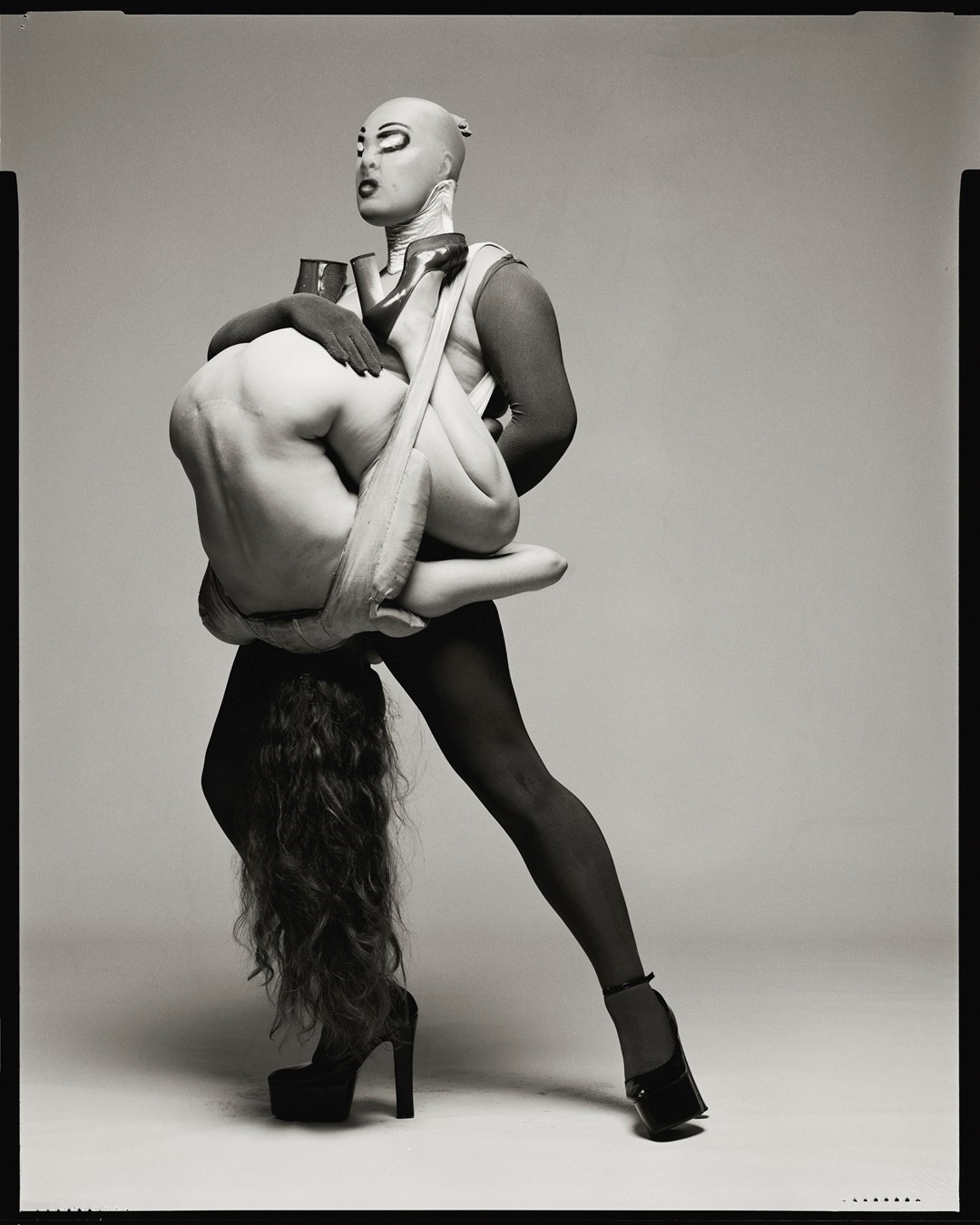

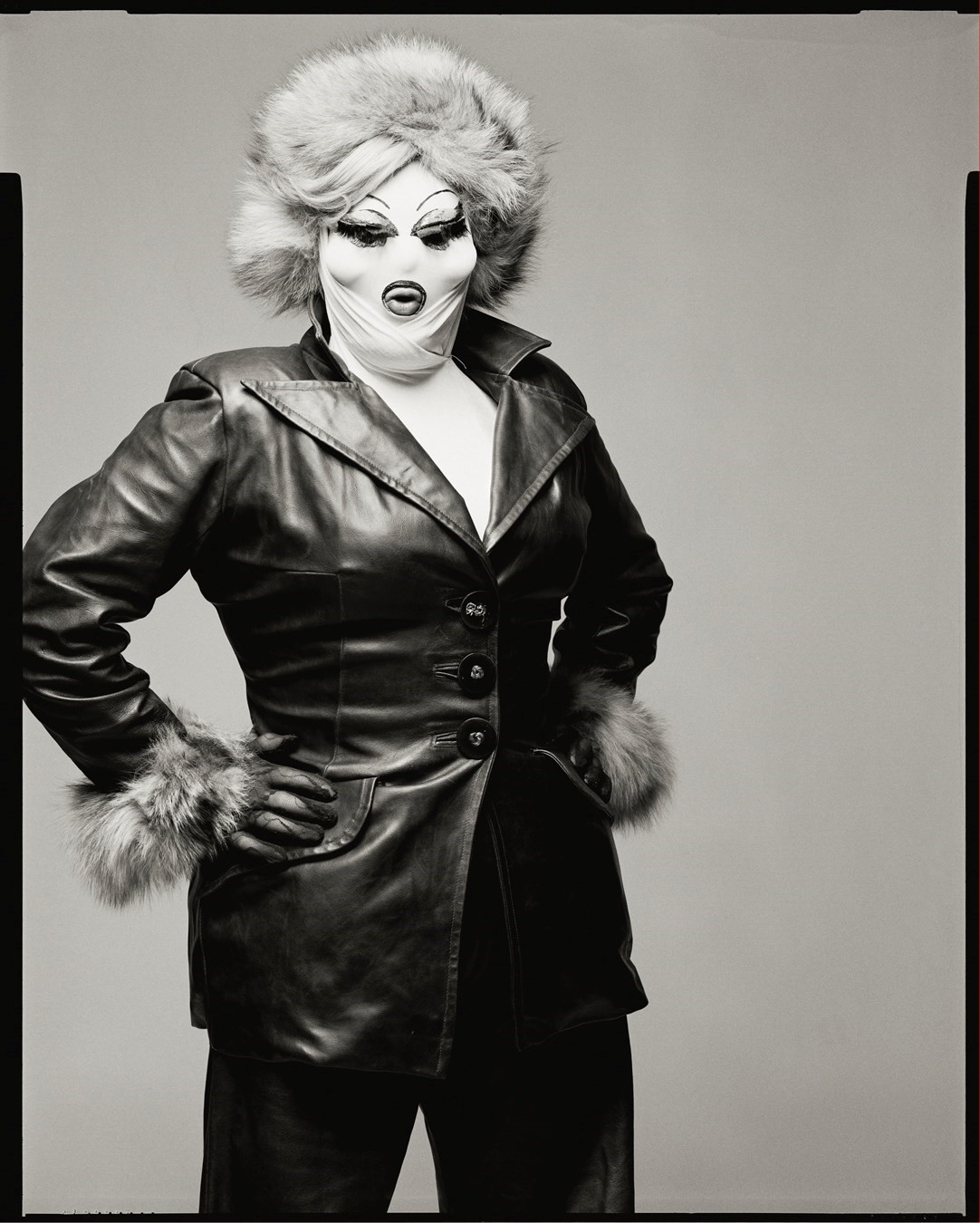

Nevertheless, the spectacular specialness of Leigh Bowery was something not only recognised by Michael Clark but by many others including Leigh Bowery himself. “Leigh thought you’re only as good as what’s in front of the camera,” says Clark. “He thought the person in front of the lens made the photo, it had nothing to do with the photographer. That was his attitude. I think he’s right. Saying that, Nick Knight knew, he recognised in Leigh something extraordinary. I just got a sense that he knew. I think when he experienced Leigh it was something very special, something really special.”

The photographer Nick Knight agrees: “The colours that he would have on his skin, that juxtaposition of colour if you looked at it abstractly, how you might look at a painting, it was just exquisite. Leigh, although he was this kind of huge, physical, sort of very loud vision, still displayed such a delicate and sensitive use of colour and texture and form – he was simply like a piece of art.”

He continues: “He was great, he was a very loud and very endearing piece of art to come into contact with. He had a very particular voice, kind of a 1950s BBC voice, but not quite. It was very soft in its delivery, but he was using language in a very definite way. He knew how to pronounce words that would make them sound important or gorgeous. And he had this rather strange accent, which comes from being Australian and living over here. But it was a little bit like talking to something from the past. It wasn’t at all clipped, because his words rolled into one another, but he just had an accent that made you think you were dealing with the establishment in some camp way. The visions you see of him are not aggressive. He wasn’t frantic. He was actually very calm. It was actually all very seductive. And of course, he knew how to dress, he knew how to wear something. The way he dressed himself, in some way it was like being in a one-to-one ballet performance, which is why I think he worked so well with Michael. I think because he was big – he was six foot three or something, I can’t remember now – and, of course, as he was always wearing high heels, he was always much bigger than that, he always just looked like a vision. He was something just so incredibly strong.”

Yet, despite all of the exquisite rigour and stylisations contained in Leigh Bowery’s ‘looks’ there was still humour and a human being at their heart. As the dancer and choreographer Les Child states: “Fakery is the new reality – I hate it. We have to get real. Leigh was about an honesty and a reality.” As Bowery’s friend, fellow Michael Clark company member and collaborator, Les Child saw all: “I saw the dark side and I saw the fun side. Eventually, people seemed to want to see things intellectually – I just wanted to be real with the bitch! We’d have six-hour phone conversations and he’d love to provoke me. I met him for the first time with Michael, at Jeremy Healy’s club. I melted at Leigh’s good manners – I love good manners. He was so charming. At the same time, I admired his drive and his intention of making an impression at any cost – he really pushed it! Michael was fascinated and respected him. He is also brilliant and generous, he never felt threatened because of his own genius. That’s why they did a lot together. Michael loved him and Trojan, he loved that madness. We loved being with them. Then Michael and Leigh fell out over the ‘I’m a Cunt’ costume – Leigh just wanted to do stuff his own way.”

“Leigh Bowery was part of that force, that force of freedom. It’s that force of delirious depravity, cheerful depravity. I talk about that because I feel like those are the values I need to support because the world can be so harshly condemning and judgmental, and that’s never going away” – Rick Owens

Bowery’s ‘I’m a Cunt’ outfit meant a certain parting of the creative ways with Michael Clark: “I’d kind of egg him on to do things, more provocative things and he’d do the same to me. I think that’s what upset him so much when I didn’t approve of the cunt. And now it seems so trivial.” If Leigh was also on the lime banquette, you can imagine them laughing about it today. “I was furious. I’m a cunt. I just didn’t want to use that word as a derogatory term. I didn’t mind him doing it in his own work. But it came to the point where he was like, ‘Well, I’m an artist in my own right.’ He wasn’t saying it, but he was kind of saying it; he wasn’t going to be told what to do and I respected that completely. It’s just unfortunate that it meant that he withdrew his services as a performer. He gave me a beautiful handwritten note saying I would understand because he loved me, and of course, I understood. I was going down a different path.”

Yet the great tragedy for Michael Clark is something far more fundamental to their friendship: “I wish he was around, I wish … I regret not coming. I was told he was going to die in a matter of days, and I didn’t come to London. I didn’t believe it. I just did not believe it. I was in Scotland at the time with mum and I was hearing rumours that I had three weeks to live. People were spreading rumours like that about me, so I took things with a pinch of salt. In the end, I couldn’t go to any memorials, I was just in shock. It’s only now he’s got a show at Tate Modern it’s making me finally believe that he’s dead.”

The legacy of Leigh Bowery is both personal and professional for his friends. As the director Baillie Walsh puts it: “I still ask myself, ‘What would Leigh do?’ Would he think I am a complete wanker? I think he probably would. How would he be fucking things up now?” As Walsh realises, the span of 30 years since his death has made the world a very different place from the one Bowery inhabited. “Our values have changed enormously. His values were very different to the ones of today. He didn’t have a financial thought, instead the challenge was all and the joy of being creative. He scraped by. Leigh saw himself as an artist but it took him time to realise this; his fashion moved into performance.”

Yet it is the fashion industry that probably owes the biggest debt to Leigh Bowery. His influence can be felt far and wide, from the seemingly conventional to the most outré outfits. The designer Kim Jones has collected Leigh Bowery’s clothing extensively: “There’s always some of Leigh in what I do. It’s the spirit more than anything. Discovering him as a teenager made a massive impact on my life and he still shapes how I see fashion now. People might not realise it, but what I do always has a debt to his humour and perversity somewhere in there.

“Well, I knew that I recognised creatures. I knew that I loved creatures,” says Rick Owens of his style inheritance. “The first time it happened, I guess, was with Bowie’s Diamond Dogs cover. I remember seeing the album cover in some discount bin and feeling exposed. I felt like someone had found me or found out about who I was. And I remember being a little bit threatened but fascinated. I remember it being a strong moment and a moment of recognition, that this was where I wanted to go and that this was my destiny or something.”

He continues: “It was that camp grotesque glam, which is very poignant at the same time. It is defiant, but poignant because somebody has to go to such great lengths to express themselves. Somebody has to go to such lengths to reject convention and to reject everything about them and carve their own path, which feels lonely and scary. There’s the thrill of courage and the threat of knowing that they’re going to have to fight for that – there’s also the thrill of seeing somebody pull it off.

“Leigh Bowery was part of that force, that force of freedom. It’s that force of delirious depravity, cheerful depravity. I talk about that because I feel like those are the values I need to support because the world can be so harshly condemning and judgmental, and that’s never going away. That’s fine because the world is supposed to be horrible and fantastic at the same time. There are always going to be those condemning forces. And then there’s always going to be the force of cheerful depravity. That’s where I need to put my support, and that is my purpose in life. It’s an otherness that someone like Leigh Bowery personifies.”

This article features in the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally now. Leigh Bowery! will go on show at Tate Modern in London from 27 February – 31 August 2025.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageLeigh Bowery, 1992Photography by Nick Knight

This story is taken from the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally now:

“Singing and dancing, man expresses himself as a member of a higher community: he has forgotten how to walk and talk, and is about to fly dancing into the heavens. His gestures express enchantment. Just as the animals now speak, and the earth yields up milk and honey, he now gives voice to supernatural sounds: he feels like a god, he himself now walks about enraptured and elated as he saw the gods walk in dreams. Man is no longer an artist, he has become a work of art.” Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

“Nightclubs!” exclaimed the late Judy Blame. “I think everyone has to go to nightclubs to learn about anything. It’s true! I think nightclubs are more important than school really. For certain people, not everyone – some people fall victim to it. But for some, they’re more important than school. I wouldn’t have met Leigh Bowery if it hadn’t been for nightclubs.”

Judy Blame said this 15 years ago and Michael Clark confirms it today, “It was Mother Blame that took Leigh under his wing – it was when Leigh worked in Burger King.” He says, sat on a lime green banquette in a Gloucester Road hotel. That makes it sound like one of his sets, it isn’t. That seat is suburban and pedestrian, something the dancer, choreographer and impresario Michael Clark will never be.

15 years ago, Judy Blame’s tale of Leigh continued: “When he first came here, he was a funny little thing, wearing horrible, long, brown monk coats. I was working on the door of a nightclub with my friend Scarlett; we said, ‘he looks interesting, get him in.’ We were shameless, there were more people stood outside Cha-Chas than inside – we were a bit choosey. Leigh said – he was green of course, still working in Burger King, just from Australia – ‘If you hadn’t let me into that club … You changed my life.’ And what he did in nightclubs was to become British haute couture with an Australian twang.”

The irrepressible spirit, provocation and talent of Judy Blame and that of his one-time monk-coated mentee Leigh Bowery, are much missed. This is the first time that Michael Clark has openly spoken about Leigh Bowery since his death 30 years ago. Since 1994, this hole in his life has been something too painful, weird and plain incomprehensible for him to contemplate. As he put it in text messages before our meeting: “I read something earlier about George Balanchine reacting to the death of Aldous Huxley. He was so shocked and upset he couldn’t put it into words … I think I have been like that about Leigh for a long time … I am thrilled he is going to be celebrated by Tate Modern. God … I miss him.”

With the approaching Tate retrospective, will the final process in the canonisation of Leigh Bowery be complete? Blessed and beatified, is Leigh Bowery about to gain some sort of sainthood in the Turbine Hall? Bowery was bigger than life when he was alive, both literally and figuratively – six foot three and always in heels, “Leigh thought you could never be too tall,” confirms Clark. Yet since his death, he has gained a further symbolism. He stands for a notion of unbridled creativity and experimentation performed largely on himself – done without establishment approval, without commercial backing, without brand ambassadorships, metric measurements and all that clap-trap of our contemporary existence. Instead, he was a world unto himself, a walking work of art and a catalyst for so many of the people who were close to him or even experienced the sight of him. If we’re being all Nietzschean about it, he was a walking, talking personification of the Dionysian, found on the dancefloor of Taboo or Terpsichorean as a teapot in a Clark-choreographed ballet; giving birth to his wife Nicola onstage or in full-blown muse mode modelling for the painter Lucian Freud. Yet he was also something very real, funny, smart, poignant and human to his friends; he was someone rather than something.

“Mark said something,” says Michael Clark of the late Mark E Smith. “‘My friends don’t amount to one hand / there are 12 people in the world, the rest are paste.’ When Leigh died, I lost one of those people, then with Mark, the same.”

“I read something earlier about George Balanchine reacting to the death of Aldous Huxley. He was so shocked and upset he couldn’t put it into words … I think I have been like that about Leigh for a long time“ – Michael Clark

Mark E Smith, frontman and driving force of The Fall, radical proponent of the English language as a lyricist and a profound working partner for both Michael Clark and Leigh Bowery; it is safe to say, he didn’t suffer fools gladly and gave dilettantes short shrift. He was not only a friend but also a catalyst for Clark, just as Leigh Bowery was. They were both exponents of and believers in the devotion and rigour it takes to make new work: “Mark responded to that. He could see how hard we worked. He was really impressed. I think he said to the band, ‘Michael’s like us. He’s really just trying to do good work, and he’s working really hard.’ And he was like that too.”

Clark continues: “Leigh was incredible. I was reminding myself of my intention when I started making work. Everyone had stripped everything down. Costumes were not costumes they were street clothes. The dance was meant to be the interesting thing. But for some of us, our only means of expression to show how we felt about the world was how we dressed. You could show how angry you were, for example. I wanted to bring people together who are equally strong. I mean, what I learned is to let people do exactly what they want to do. You can’t really tell people what to do and get the best out of them, so let them do what they’re interested in.”

In this way – and more – Leigh Bowery became an essential part of the expression of Michael Clark’s ‘YES Manifesto’, written in 1984 in response to American dancer and choreographer Yvonne Rainer’s ‘NO Manifesto.’

Yes to spectacle.

Yes to virtuosity.

Yes to transformations and magic and make-believe.

Yes to the glamour and transcendency of the star image.

Yes to the heroic.

Yes to the anti-heroic.

Yes to trash imagery.

Yes to the involvement of the performer or spectator.

Yes to style.

Yes to camp.

Yes to seduction by the wiles of the performer.

Yes to eccentricity.

Yes to moving or being moved.

“With Leigh, the first thing we did was actually very conventional,” explains Clark. “It was a narrative of Echo and Narcissus. He came into rehearsal, and I told him, ‘She’s Echo and he’s Narcissus.’ But then how he was dressing himself, with Trojan and David – it’s what we called ‘The Three Kings’ – it was platform shoes, face and body paint, it was quite god-like in a way. That’s how he looked when I first met him. I’d seen him in Jeremy Healy’s club, Circus. I went to the toilet, where he was hanging out with Trojan and David, and asked him if he would do costumes for me. I then had to meet him in the daytime for the first time, and he was in a totally straight look with obviously something odd about it. He was very quiet, but so polite in those days, even later on he was very polite. He sat in the corner and I don’t know what he was thinking.”

Of course, as time went on their relationship in work and life became inseparable. “Leigh educated me as much as I did him,” says Clark of their connection. “I remember him taking me around a de Kooning exhibition in Amsterdam, and it meant nothing to me. He was trying to convey to me how it worked for him and what he thought it was about. He was very patient – he also did the same with my work. He made me aware of how, when I thought dance was just pretentious nonsense, it meant something. Sometimes I’d fall asleep, I’d wake up with my own work on a video, on the TV screen and I’d think ‘What the fuck is this? This is ridiculous,’ then I’d realise it was actually my work. So, I’ve always had a bit of perspective on dance, but Leigh would remind me of the worth. He was, I guess, a kind of objective eye. He was in rehearsals and would make me aware of how good what I was doing was. He was very good at bringing everyone together. That was his kind of attitude, he’d say ‘Somebody’s got to do it, if we don’t do it what is there?’ That was his attitude.”

Leigh Bowery’s specialness, his attitude, his humour and star quality led to him being part of the performance as well as one of the costume designers. “I wanted him around,” explains Clark. “At that time, if I was fond of somebody, I just got them in the company and then they would become part of the performance. I mean, a lot of critics kind of accused me of just thinking my life was so interesting I’d put it on stage and that was enough. That wasn’t really what I was doing. Although the only element of that might have been this wanting to embrace my mum and Leigh.”

Nevertheless, the spectacular specialness of Leigh Bowery was something not only recognised by Michael Clark but by many others including Leigh Bowery himself. “Leigh thought you’re only as good as what’s in front of the camera,” says Clark. “He thought the person in front of the lens made the photo, it had nothing to do with the photographer. That was his attitude. I think he’s right. Saying that, Nick Knight knew, he recognised in Leigh something extraordinary. I just got a sense that he knew. I think when he experienced Leigh it was something very special, something really special.”

The photographer Nick Knight agrees: “The colours that he would have on his skin, that juxtaposition of colour if you looked at it abstractly, how you might look at a painting, it was just exquisite. Leigh, although he was this kind of huge, physical, sort of very loud vision, still displayed such a delicate and sensitive use of colour and texture and form – he was simply like a piece of art.”

He continues: “He was great, he was a very loud and very endearing piece of art to come into contact with. He had a very particular voice, kind of a 1950s BBC voice, but not quite. It was very soft in its delivery, but he was using language in a very definite way. He knew how to pronounce words that would make them sound important or gorgeous. And he had this rather strange accent, which comes from being Australian and living over here. But it was a little bit like talking to something from the past. It wasn’t at all clipped, because his words rolled into one another, but he just had an accent that made you think you were dealing with the establishment in some camp way. The visions you see of him are not aggressive. He wasn’t frantic. He was actually very calm. It was actually all very seductive. And of course, he knew how to dress, he knew how to wear something. The way he dressed himself, in some way it was like being in a one-to-one ballet performance, which is why I think he worked so well with Michael. I think because he was big – he was six foot three or something, I can’t remember now – and, of course, as he was always wearing high heels, he was always much bigger than that, he always just looked like a vision. He was something just so incredibly strong.”

Yet, despite all of the exquisite rigour and stylisations contained in Leigh Bowery’s ‘looks’ there was still humour and a human being at their heart. As the dancer and choreographer Les Child states: “Fakery is the new reality – I hate it. We have to get real. Leigh was about an honesty and a reality.” As Bowery’s friend, fellow Michael Clark company member and collaborator, Les Child saw all: “I saw the dark side and I saw the fun side. Eventually, people seemed to want to see things intellectually – I just wanted to be real with the bitch! We’d have six-hour phone conversations and he’d love to provoke me. I met him for the first time with Michael, at Jeremy Healy’s club. I melted at Leigh’s good manners – I love good manners. He was so charming. At the same time, I admired his drive and his intention of making an impression at any cost – he really pushed it! Michael was fascinated and respected him. He is also brilliant and generous, he never felt threatened because of his own genius. That’s why they did a lot together. Michael loved him and Trojan, he loved that madness. We loved being with them. Then Michael and Leigh fell out over the ‘I’m a Cunt’ costume – Leigh just wanted to do stuff his own way.”

“Leigh Bowery was part of that force, that force of freedom. It’s that force of delirious depravity, cheerful depravity. I talk about that because I feel like those are the values I need to support because the world can be so harshly condemning and judgmental, and that’s never going away” – Rick Owens

Bowery’s ‘I’m a Cunt’ outfit meant a certain parting of the creative ways with Michael Clark: “I’d kind of egg him on to do things, more provocative things and he’d do the same to me. I think that’s what upset him so much when I didn’t approve of the cunt. And now it seems so trivial.” If Leigh was also on the lime banquette, you can imagine them laughing about it today. “I was furious. I’m a cunt. I just didn’t want to use that word as a derogatory term. I didn’t mind him doing it in his own work. But it came to the point where he was like, ‘Well, I’m an artist in my own right.’ He wasn’t saying it, but he was kind of saying it; he wasn’t going to be told what to do and I respected that completely. It’s just unfortunate that it meant that he withdrew his services as a performer. He gave me a beautiful handwritten note saying I would understand because he loved me, and of course, I understood. I was going down a different path.”

Yet the great tragedy for Michael Clark is something far more fundamental to their friendship: “I wish he was around, I wish … I regret not coming. I was told he was going to die in a matter of days, and I didn’t come to London. I didn’t believe it. I just did not believe it. I was in Scotland at the time with mum and I was hearing rumours that I had three weeks to live. People were spreading rumours like that about me, so I took things with a pinch of salt. In the end, I couldn’t go to any memorials, I was just in shock. It’s only now he’s got a show at Tate Modern it’s making me finally believe that he’s dead.”

The legacy of Leigh Bowery is both personal and professional for his friends. As the director Baillie Walsh puts it: “I still ask myself, ‘What would Leigh do?’ Would he think I am a complete wanker? I think he probably would. How would he be fucking things up now?” As Walsh realises, the span of 30 years since his death has made the world a very different place from the one Bowery inhabited. “Our values have changed enormously. His values were very different to the ones of today. He didn’t have a financial thought, instead the challenge was all and the joy of being creative. He scraped by. Leigh saw himself as an artist but it took him time to realise this; his fashion moved into performance.”

Yet it is the fashion industry that probably owes the biggest debt to Leigh Bowery. His influence can be felt far and wide, from the seemingly conventional to the most outré outfits. The designer Kim Jones has collected Leigh Bowery’s clothing extensively: “There’s always some of Leigh in what I do. It’s the spirit more than anything. Discovering him as a teenager made a massive impact on my life and he still shapes how I see fashion now. People might not realise it, but what I do always has a debt to his humour and perversity somewhere in there.

“Well, I knew that I recognised creatures. I knew that I loved creatures,” says Rick Owens of his style inheritance. “The first time it happened, I guess, was with Bowie’s Diamond Dogs cover. I remember seeing the album cover in some discount bin and feeling exposed. I felt like someone had found me or found out about who I was. And I remember being a little bit threatened but fascinated. I remember it being a strong moment and a moment of recognition, that this was where I wanted to go and that this was my destiny or something.”

He continues: “It was that camp grotesque glam, which is very poignant at the same time. It is defiant, but poignant because somebody has to go to such great lengths to express themselves. Somebody has to go to such lengths to reject convention and to reject everything about them and carve their own path, which feels lonely and scary. There’s the thrill of courage and the threat of knowing that they’re going to have to fight for that – there’s also the thrill of seeing somebody pull it off.

“Leigh Bowery was part of that force, that force of freedom. It’s that force of delirious depravity, cheerful depravity. I talk about that because I feel like those are the values I need to support because the world can be so harshly condemning and judgmental, and that’s never going away. That’s fine because the world is supposed to be horrible and fantastic at the same time. There are always going to be those condemning forces. And then there’s always going to be the force of cheerful depravity. That’s where I need to put my support, and that is my purpose in life. It’s an otherness that someone like Leigh Bowery personifies.”

This article features in the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of Another Man, which is on sale internationally now. Leigh Bowery! will go on show at Tate Modern in London from 27 February – 31 August 2025.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.