Rewrite

For Objects of Legacy, Casper Mueller Kneer created an experimental dinner and cocktail event at the historic Espace Niemeyer site to celebrate the adidas Stan Smith

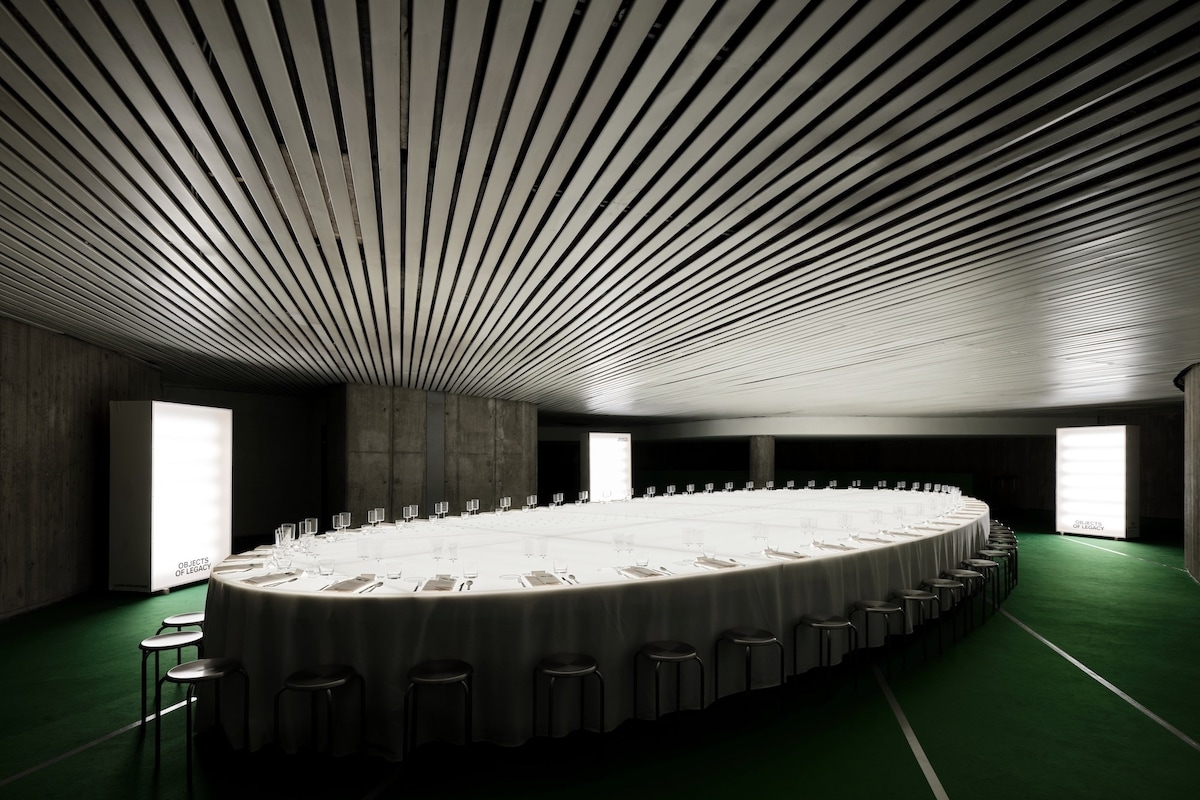

Beneath a dome that once watched over the French Communist Party’s debates in the 1970s, a large self-illuminating dinner table is prepared. Its oval shape stands in the middle of a room noisy with conversation and Object Blue’s elegant, beat-driven dinner soundtrack. Guests like Gabbriette, Cruz Beckham, Paloma Elsesser, Damson Idris, ASAP Nast and Pusha T gather under a DayGlo hanging light box. The setting looks, not at all accidentally, like Kubrick’s vision of a war room in Dr. Strangelove. And it is a party.

During Paris Fashion Week Men’s in late January, Another Man partnered with adidas Originals and BeGood Studios to celebrate the legacy of the Stan Smith shoe in the incredible Unesco Heritage Site Espace Niemeyer. The evening was designed by culinary studio We Are Ona and Casper Mueller Kneer, the architectural practice behind similarly ambitious projects for the likes of the White Cube Gallery in Bermondsey, the TIME flagship building in Seoul and the flagship Saint Laurent building on the Champs-Élysées.

For the event, titled Objects of Legacy, they led the design of the space, in particular its large, oval dining table, which was the centrepiece of the evening. They brought a new approach to lighting the Espace Niemeyer, looking for intensity, and attempting to avoid obvious choices. We asked Olaf Kneer, founding partner and one of the directors of Casper Mueller Kneer, about his vision for the evening, and what it was like to work in such incredible surroundings.

Ralph Jeffreys: What was the overall vision you had when approaching the Objects of Legacy event, in collaboration with adidas Originals?

Olaf Kneer: I think we knew it was going to have to be something really iconic. Geometry is super important for us, which sounds like a stupid thing to say because it’s so obvious. But it’s not geometry because of aesthetics, but geometry in relation to human interaction. Like with the dinner table. How big is it? How close do you sit together? In the end, we made it as small as possible so there was a kind of intimacy, but it was still very comfortable.

Then we thought about Kubrick’s War Room in Dr. Strangelove, this kind of ominous space without anything around it. And in the end, the right thing to do was to switch all the other lights off so the intensity was around the table.

And then the other thing is we’re really interested in light. Again, this sounds obvious, but you can do quite a lot with light. We often use ceiling light boxes to create setups where you have a table and a light in the ceiling. Those two things somehow belong together. They could be in the middle of anywhere – in the forest, on a runway – but they still create a space.

Those two elements really made the space. That was it – extremely simple tools, but as effective as possible. In the end, the material wasn’t so important anymore, even though we had quite a lot of fun with that as well. We had some nice stitching details that maybe not everybody saw. There was green stitching in the fabric that coated one set of light boxes. And then upstairs, they were a bit different. There was this mesh idea—they became almost ephemeral. A bit ghostlike.

And then with the self-illuminating table, we thought it would be fun to have transparent plates. I enjoyed that tremendously, this additional layer of light shining through food. And of course, the culinary designers (We Are Ona) brought these beautiful touches with the napkins with the stitching in them. I stole mine, of course, it was such a beautiful object.

RJ: Can you tell me more about the specific design decisions that explored the textures and visual identity of the Stan Smith and its wider cultural impact? For example, the tape on the floor to nod to the layout of a tennis court and the tennis net reference for the layout’s bespoke metal mesh bar.

OK: Conceptually, we sought to reference aspects, some very ephemeral, that remind us of the game of tennis. There are certain tennis elements that are relatively permanent, such as the grass or turf surfaces and the associated colour green, the white lines that are drawn unto the surface to delineate the playing field, and the tennis net. These are all essential to the game. The colour green was already present in parts of Niemeyer’s building so we obviously played with that, but we added this layer to the dining set-up, where we laid a temporary turf, complete with lines redrawing the court taped onto it. The use of mesh for the light boxes, dj table and bar are references to the tennis net.

RJ: What extra subtle details can you reveal here that people might have spotted on the night?

OK: Other more ephemeral aspects relate to tennis being a game that requires a lot of setting up. Benches, umbrellas, court covers etc are all elements that need to be brought in, as are the equipment for playing, the rackets, the towels etc. We particularly wanted to reference the sports bags and tennis clothes, traditionally white cotton, which we used for dressing the light boxes in the dining space, they also had handles which were stitched to the fabric to allow them to be carried and positioned in the field. The largest element was the actual dining table, which we dressed in white cotton cloth. Seams were stitched in green and lines of green dots were printed onto the cloth in a diagonal pattern. These were quite subtle and perhaps not spotted by everyone, but they were elements we really enjoyed bringing in.

RJ: What was the early design process like? Obviously you ended up taking some inspiration from Dr. Strangelove, which is maybe not a connection most people would make when they say, “Let’s do a party.”

OK: It’s always tricky, I have to say. This is the most nerve-wracking part for me, because it’s the first reaction to a brief. Sometimes there are more gentle ways into a collaboration where one set of ideas bounces back into another set, and together you make something emerge. But this was a really fast process, so you just have to stick your head out and be quite courageous about it. In the end it worked out really well.

When we work on other events with more time, sometimes we come with eight ideas – different possible directions to go in. And then we find out what resonates and what doesn’t. Because it had to be fast, we didn’t have the luxury of long conversations, mulling over things. But we enjoy this process, and we’ve found a way of working that allows ideas to emerge without having an idea beforehand. Quite often we don’t have a single idea, but we have a lot of interests.

RJ: I know you mentioned it a little bit earlier, but obviously it’s such an iconic building. What are your thoughts about it as a design and how did this enhance your concept for Objects of Legacy?

OK: It’s really incredible. It’s a bit of a miracle to have projects like this. When you’re in the building, you can see that it was done very cheaply. They didn’t have a lot of money, even though it looks grand and heroic. The detailing is very, very simple – extremely cheap in some corners. The ceilings are made from plasterboard, there are gaps everywhere, the lighting is terrible, everything is cobbled together.

But the trust in the architect to build such a thing was amazing. And for the architect to be so generous – he was a very famous person at the time – for him to embark on this, to work under these conditions, was pretty cool. He’s actually not my favourite person in the world, even though I really appreciate what he’s done for architecture. He’s a little bit too male, a bit too dominant. But what I enjoy about his work is that it’s really fun. It’s very sensuous, single-minded. So it was a real treat to be in that building.

RJ: I wanted to ask about the dome itself. When I’ve seen pictures, it looks like quite an imposing thing to be under. What was the process of creating an atmosphere for a party in such a huge space, all the while exploring the legacy of the iconic adidas Stan Smith?

OK: It’s really interesting because our big revelation when we visited was that it’s not very big. That was really shocking. Everybody had the same reaction walking into the space: “This is quite small, really.” We were fifteen or twenty people and we felt it wasn’t that empty.

We were obviously worried about that sequence of the event: what about the first person arriving? Are they going to feel weird being first? But in this kind of space, you feel almost domestic. You feel you can inhabit this space. It almost felt like somebody’s home. I could imagine living there, it was strange. So it ended up being more than enough – those two light boxes and two tables. We didn’t need anything more. I think it just photographs very grand because it doesn’t have so many details. It’s just one thing.

RJ: Looking at some of the work you’ve done, you’re often interested in creating continuous journeys through spaces. How did you bring that to this project?

OK: I think it is an important aspect, especially in projects that are big. It creates a sense of identity for different spaces. As a user of a building, you have certain experiences that you relate to, qualities of spaces that you remember. In very large buildings, what I don’t like is when you have a repetition of spaces and it feels endless – you can’t orient yourself. That’s something we try to avoid.

It’s also an opportunity for us to be playful. Quite often spaces do repeat, but because we have more than one idea for a space, there are all these variations we can play out. With Espace Niemeyer it was more about finding these qualities and working with them.

RJ: Mentioning fashion shows, did any of the past shows – I think Prada’s was the first – come into your thinking or inspire you in any way?

OK: Absolutely, and we absolutely wanted to stay away from any of that imagery. In this instance, with the lighting specifically, I worked very hard against everybody. There was a great lighting designer involved, and he’d brought tons of equipment. He was going to light up the thing. I was like, “Switch everything off, please. Just take it all away.” He was a little bit disappointed. But then later, during the DJ set, those lights came on.

It was a very deliberate decision not to redraw the geometry, not to show that it’s a circle. We really wanted to make our own space with light and create this intensity at floor level. And we’re always very careful not to reference any shows unless they were really historic or seminal moments. We stay away from anything anybody’s done before. It’s a bit of a minefield, really.

RJ: Looking to the future, do you have any events planned like this? Do you want to do more things like this?

OK: I’d love to do more. It’s really super refreshing to do things with different timeframes. Obviously you can’t just do this – it would be very difficult to sustain yourself as a practice. But I’d love to do more of these light-hearted events that are quite impactful. We’re designing the next show for Saint Laurent as well, the women’s show in Paris. That’s also really good fun. Very different, as you can imagine. We’re working on these shows almost continuously – we finish one and start the next.

By the way, that’s another interesting thing about the Adidas objects. On the night, everybody realised that these are actually not throw-away items. They have an afterlife. They should be used in-store, or the table could be taken apart. This kind of afterlife of an event is becoming more and more important with ecology – the idea of looking after resources and not just producing things that are thrown away. So I hope they are doing that.

RJ: And I wondered, having just put one on, what do you think makes a perfect party?

OK: A perfect party? Wow, that’s a nice question. I like that. There would be many perfect parties, but I think it’s really nice when everybody gets a little bit delirious, you know, and they all let go. There’s different ways of doing that, maybe it’s the music or something else, but I like these kind of slightly delirious moments. Parties are brilliant to design because of this quality – people going nuts. Hopefully unexpected things happen.

I also really like moments when people are friendly to one another. I don’t know what’s needed to create that. You had that a lot in the old clubbing scene, people just coming up and chatting to you. So I think that’s what I like in a party: slightly delirious and friendly. And thumpy.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

For Objects of Legacy, Casper Mueller Kneer created an experimental dinner and cocktail event at the historic Espace Niemeyer site to celebrate the adidas Stan Smith

Beneath a dome that once watched over the French Communist Party’s debates in the 1970s, a large self-illuminating dinner table is prepared. Its oval shape stands in the middle of a room noisy with conversation and Object Blue’s elegant, beat-driven dinner soundtrack. Guests like Gabbriette, Cruz Beckham, Paloma Elsesser, Damson Idris, ASAP Nast and Pusha T gather under a DayGlo hanging light box. The setting looks, not at all accidentally, like Kubrick’s vision of a war room in Dr. Strangelove. And it is a party.

During Paris Fashion Week Men’s in late January, Another Man partnered with adidas Originals and BeGood Studios to celebrate the legacy of the Stan Smith shoe in the incredible Unesco Heritage Site Espace Niemeyer. The evening was designed by culinary studio We Are Ona and Casper Mueller Kneer, the architectural practice behind similarly ambitious projects for the likes of the White Cube Gallery in Bermondsey, the TIME flagship building in Seoul and the flagship Saint Laurent building on the Champs-Élysées.

For the event, titled Objects of Legacy, they led the design of the space, in particular its large, oval dining table, which was the centrepiece of the evening. They brought a new approach to lighting the Espace Niemeyer, looking for intensity, and attempting to avoid obvious choices. We asked Olaf Kneer, founding partner and one of the directors of Casper Mueller Kneer, about his vision for the evening, and what it was like to work in such incredible surroundings.

Ralph Jeffreys: What was the overall vision you had when approaching the Objects of Legacy event, in collaboration with adidas Originals?

Olaf Kneer: I think we knew it was going to have to be something really iconic. Geometry is super important for us, which sounds like a stupid thing to say because it’s so obvious. But it’s not geometry because of aesthetics, but geometry in relation to human interaction. Like with the dinner table. How big is it? How close do you sit together? In the end, we made it as small as possible so there was a kind of intimacy, but it was still very comfortable.

Then we thought about Kubrick’s War Room in Dr. Strangelove, this kind of ominous space without anything around it. And in the end, the right thing to do was to switch all the other lights off so the intensity was around the table.

And then the other thing is we’re really interested in light. Again, this sounds obvious, but you can do quite a lot with light. We often use ceiling light boxes to create setups where you have a table and a light in the ceiling. Those two things somehow belong together. They could be in the middle of anywhere – in the forest, on a runway – but they still create a space.

Those two elements really made the space. That was it – extremely simple tools, but as effective as possible. In the end, the material wasn’t so important anymore, even though we had quite a lot of fun with that as well. We had some nice stitching details that maybe not everybody saw. There was green stitching in the fabric that coated one set of light boxes. And then upstairs, they were a bit different. There was this mesh idea—they became almost ephemeral. A bit ghostlike.

And then with the self-illuminating table, we thought it would be fun to have transparent plates. I enjoyed that tremendously, this additional layer of light shining through food. And of course, the culinary designers (We Are Ona) brought these beautiful touches with the napkins with the stitching in them. I stole mine, of course, it was such a beautiful object.

RJ: Can you tell me more about the specific design decisions that explored the textures and visual identity of the Stan Smith and its wider cultural impact? For example, the tape on the floor to nod to the layout of a tennis court and the tennis net reference for the layout’s bespoke metal mesh bar.

OK: Conceptually, we sought to reference aspects, some very ephemeral, that remind us of the game of tennis. There are certain tennis elements that are relatively permanent, such as the grass or turf surfaces and the associated colour green, the white lines that are drawn unto the surface to delineate the playing field, and the tennis net. These are all essential to the game. The colour green was already present in parts of Niemeyer’s building so we obviously played with that, but we added this layer to the dining set-up, where we laid a temporary turf, complete with lines redrawing the court taped onto it. The use of mesh for the light boxes, dj table and bar are references to the tennis net.

RJ: What extra subtle details can you reveal here that people might have spotted on the night?

OK: Other more ephemeral aspects relate to tennis being a game that requires a lot of setting up. Benches, umbrellas, court covers etc are all elements that need to be brought in, as are the equipment for playing, the rackets, the towels etc. We particularly wanted to reference the sports bags and tennis clothes, traditionally white cotton, which we used for dressing the light boxes in the dining space, they also had handles which were stitched to the fabric to allow them to be carried and positioned in the field. The largest element was the actual dining table, which we dressed in white cotton cloth. Seams were stitched in green and lines of green dots were printed onto the cloth in a diagonal pattern. These were quite subtle and perhaps not spotted by everyone, but they were elements we really enjoyed bringing in.

RJ: What was the early design process like? Obviously you ended up taking some inspiration from Dr. Strangelove, which is maybe not a connection most people would make when they say, “Let’s do a party.”

OK: It’s always tricky, I have to say. This is the most nerve-wracking part for me, because it’s the first reaction to a brief. Sometimes there are more gentle ways into a collaboration where one set of ideas bounces back into another set, and together you make something emerge. But this was a really fast process, so you just have to stick your head out and be quite courageous about it. In the end it worked out really well.

When we work on other events with more time, sometimes we come with eight ideas – different possible directions to go in. And then we find out what resonates and what doesn’t. Because it had to be fast, we didn’t have the luxury of long conversations, mulling over things. But we enjoy this process, and we’ve found a way of working that allows ideas to emerge without having an idea beforehand. Quite often we don’t have a single idea, but we have a lot of interests.

RJ: I know you mentioned it a little bit earlier, but obviously it’s such an iconic building. What are your thoughts about it as a design and how did this enhance your concept for Objects of Legacy?

OK: It’s really incredible. It’s a bit of a miracle to have projects like this. When you’re in the building, you can see that it was done very cheaply. They didn’t have a lot of money, even though it looks grand and heroic. The detailing is very, very simple – extremely cheap in some corners. The ceilings are made from plasterboard, there are gaps everywhere, the lighting is terrible, everything is cobbled together.

But the trust in the architect to build such a thing was amazing. And for the architect to be so generous – he was a very famous person at the time – for him to embark on this, to work under these conditions, was pretty cool. He’s actually not my favourite person in the world, even though I really appreciate what he’s done for architecture. He’s a little bit too male, a bit too dominant. But what I enjoy about his work is that it’s really fun. It’s very sensuous, single-minded. So it was a real treat to be in that building.

RJ: I wanted to ask about the dome itself. When I’ve seen pictures, it looks like quite an imposing thing to be under. What was the process of creating an atmosphere for a party in such a huge space, all the while exploring the legacy of the iconic adidas Stan Smith?

OK: It’s really interesting because our big revelation when we visited was that it’s not very big. That was really shocking. Everybody had the same reaction walking into the space: “This is quite small, really.” We were fifteen or twenty people and we felt it wasn’t that empty.

We were obviously worried about that sequence of the event: what about the first person arriving? Are they going to feel weird being first? But in this kind of space, you feel almost domestic. You feel you can inhabit this space. It almost felt like somebody’s home. I could imagine living there, it was strange. So it ended up being more than enough – those two light boxes and two tables. We didn’t need anything more. I think it just photographs very grand because it doesn’t have so many details. It’s just one thing.

RJ: Looking at some of the work you’ve done, you’re often interested in creating continuous journeys through spaces. How did you bring that to this project?

OK: I think it is an important aspect, especially in projects that are big. It creates a sense of identity for different spaces. As a user of a building, you have certain experiences that you relate to, qualities of spaces that you remember. In very large buildings, what I don’t like is when you have a repetition of spaces and it feels endless – you can’t orient yourself. That’s something we try to avoid.

It’s also an opportunity for us to be playful. Quite often spaces do repeat, but because we have more than one idea for a space, there are all these variations we can play out. With Espace Niemeyer it was more about finding these qualities and working with them.

RJ: Mentioning fashion shows, did any of the past shows – I think Prada’s was the first – come into your thinking or inspire you in any way?

OK: Absolutely, and we absolutely wanted to stay away from any of that imagery. In this instance, with the lighting specifically, I worked very hard against everybody. There was a great lighting designer involved, and he’d brought tons of equipment. He was going to light up the thing. I was like, “Switch everything off, please. Just take it all away.” He was a little bit disappointed. But then later, during the DJ set, those lights came on.

It was a very deliberate decision not to redraw the geometry, not to show that it’s a circle. We really wanted to make our own space with light and create this intensity at floor level. And we’re always very careful not to reference any shows unless they were really historic or seminal moments. We stay away from anything anybody’s done before. It’s a bit of a minefield, really.

RJ: Looking to the future, do you have any events planned like this? Do you want to do more things like this?

OK: I’d love to do more. It’s really super refreshing to do things with different timeframes. Obviously you can’t just do this – it would be very difficult to sustain yourself as a practice. But I’d love to do more of these light-hearted events that are quite impactful. We’re designing the next show for Saint Laurent as well, the women’s show in Paris. That’s also really good fun. Very different, as you can imagine. We’re working on these shows almost continuously – we finish one and start the next.

By the way, that’s another interesting thing about the Adidas objects. On the night, everybody realised that these are actually not throw-away items. They have an afterlife. They should be used in-store, or the table could be taken apart. This kind of afterlife of an event is becoming more and more important with ecology – the idea of looking after resources and not just producing things that are thrown away. So I hope they are doing that.

RJ: And I wondered, having just put one on, what do you think makes a perfect party?

OK: A perfect party? Wow, that’s a nice question. I like that. There would be many perfect parties, but I think it’s really nice when everybody gets a little bit delirious, you know, and they all let go. There’s different ways of doing that, maybe it’s the music or something else, but I like these kind of slightly delirious moments. Parties are brilliant to design because of this quality – people going nuts. Hopefully unexpected things happen.

I also really like moments when people are friendly to one another. I don’t know what’s needed to create that. You had that a lot in the old clubbing scene, people just coming up and chatting to you. So I think that’s what I like in a party: slightly delirious and friendly. And thumpy.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.