Rewrite

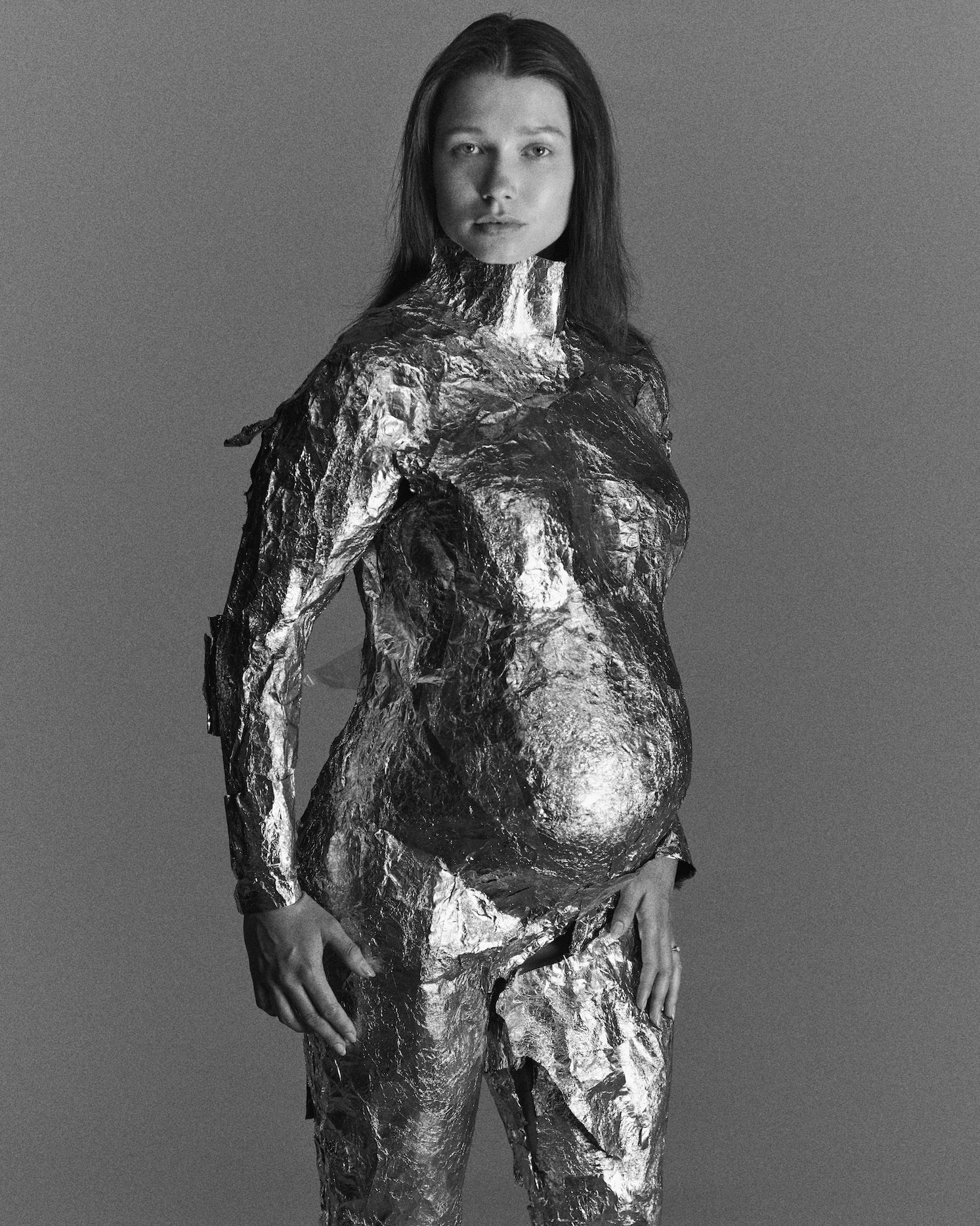

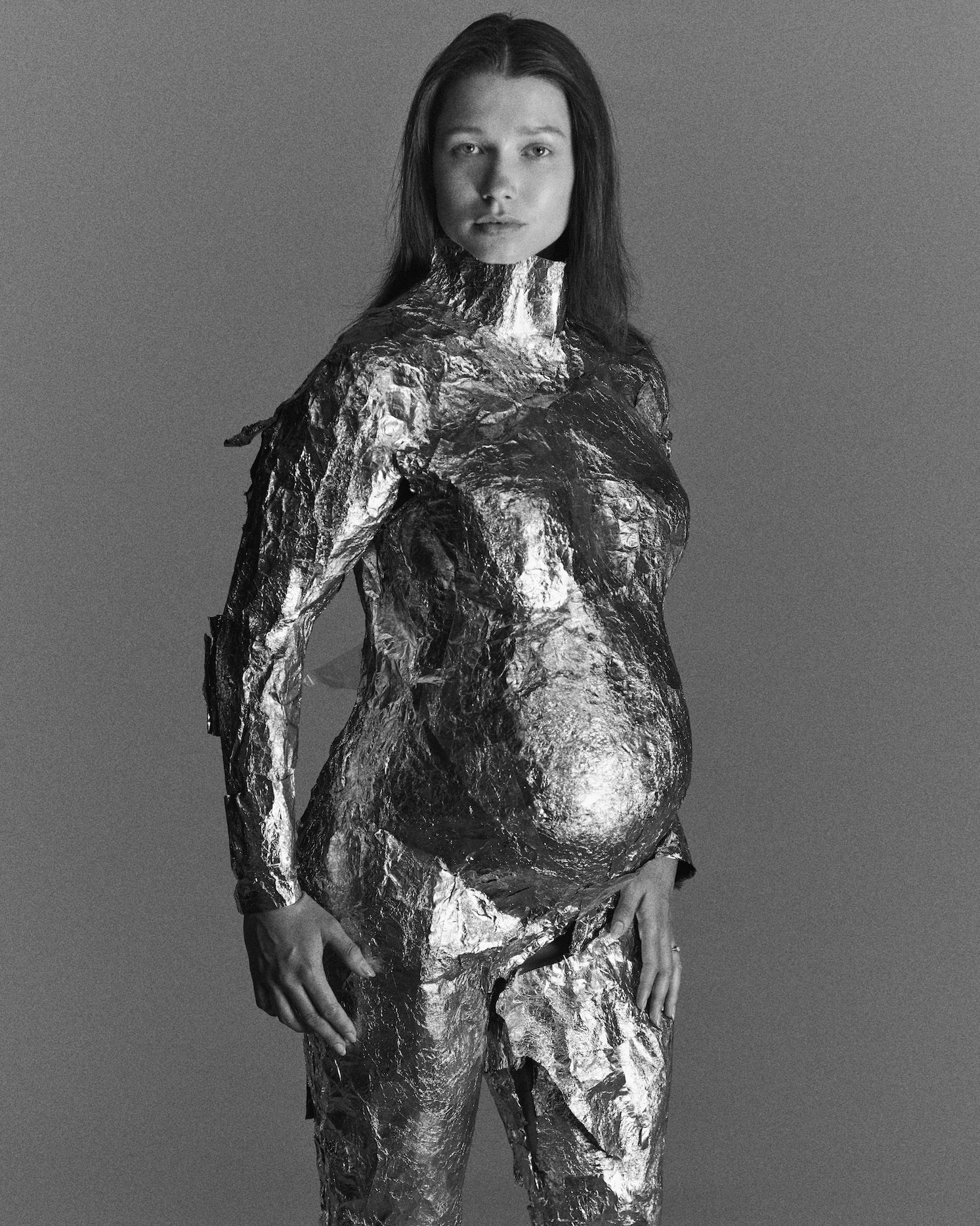

Lead ImageLie Ning is wearing a suit, shirt and tie gilded in 24-carat gold by PONTEPhotography by Larissa Hofmann, Styling by Rebecca Perlmutar

This story is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine:

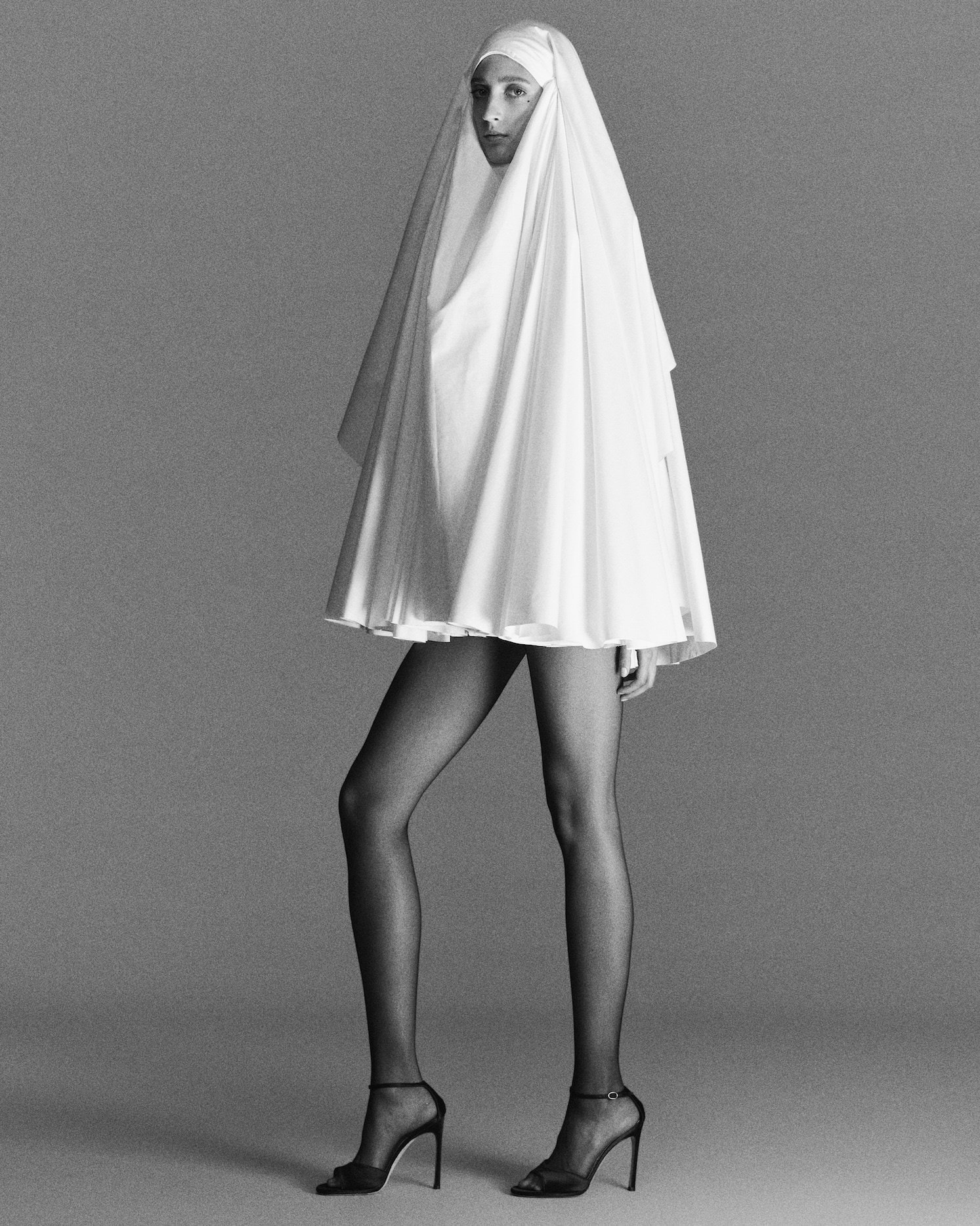

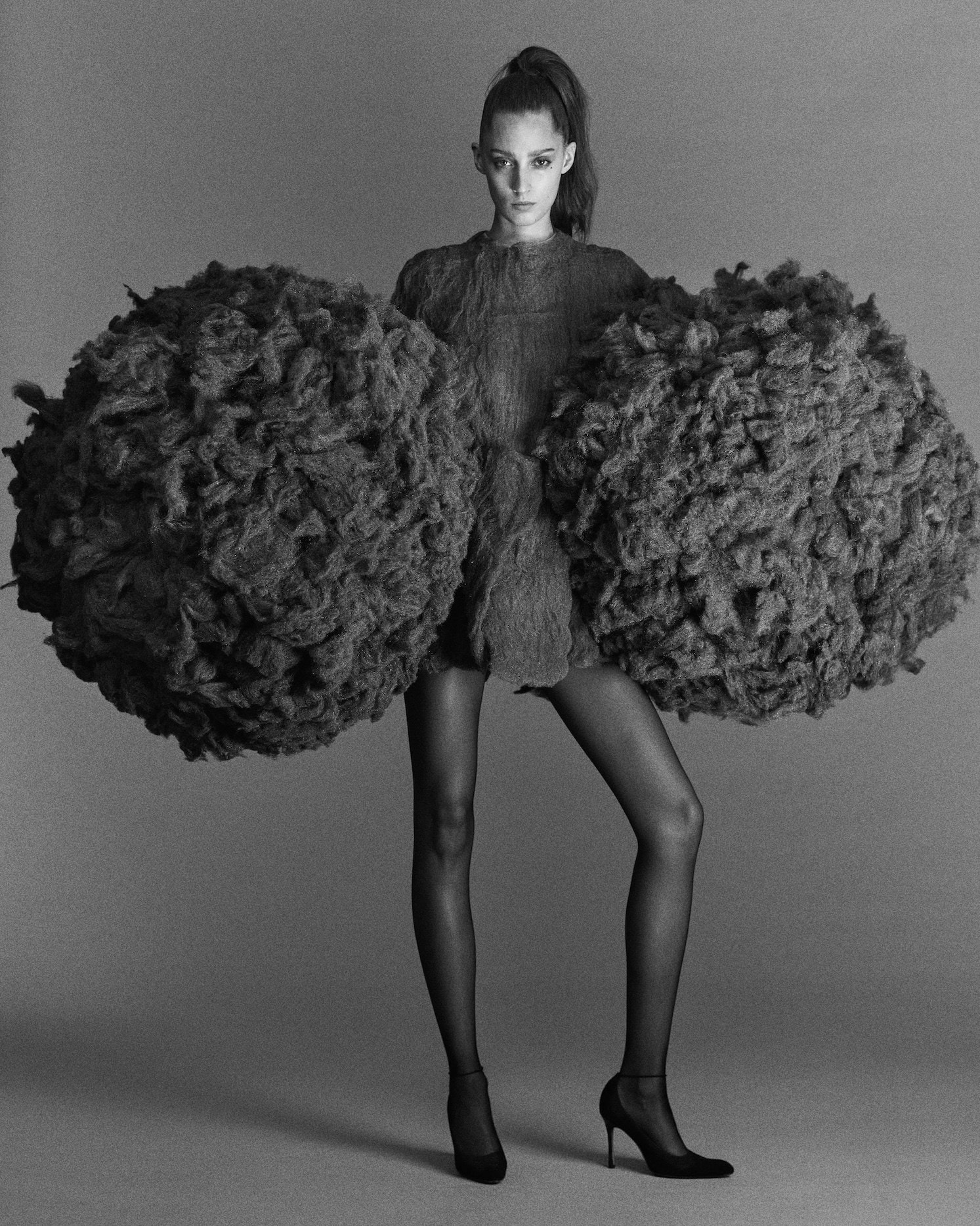

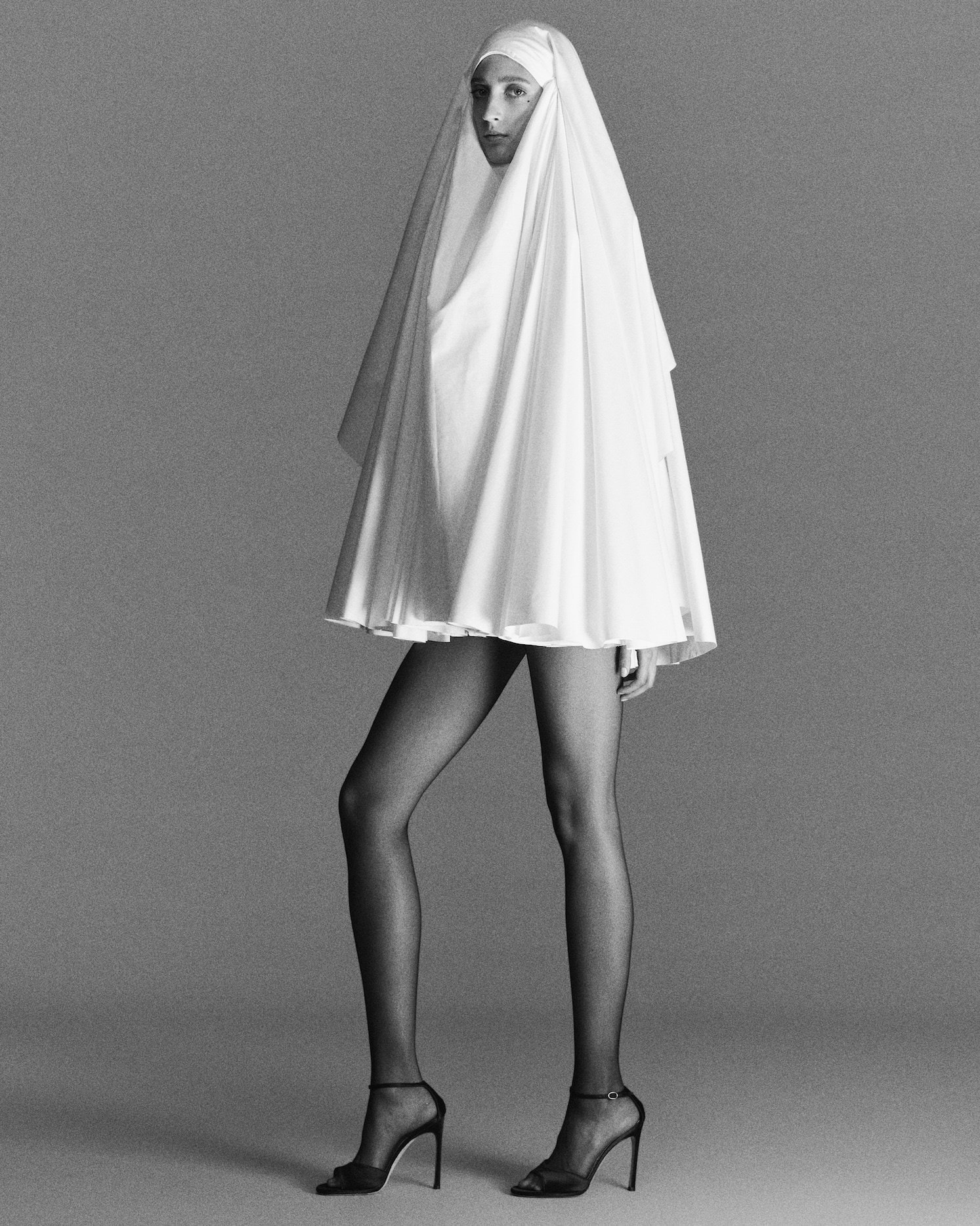

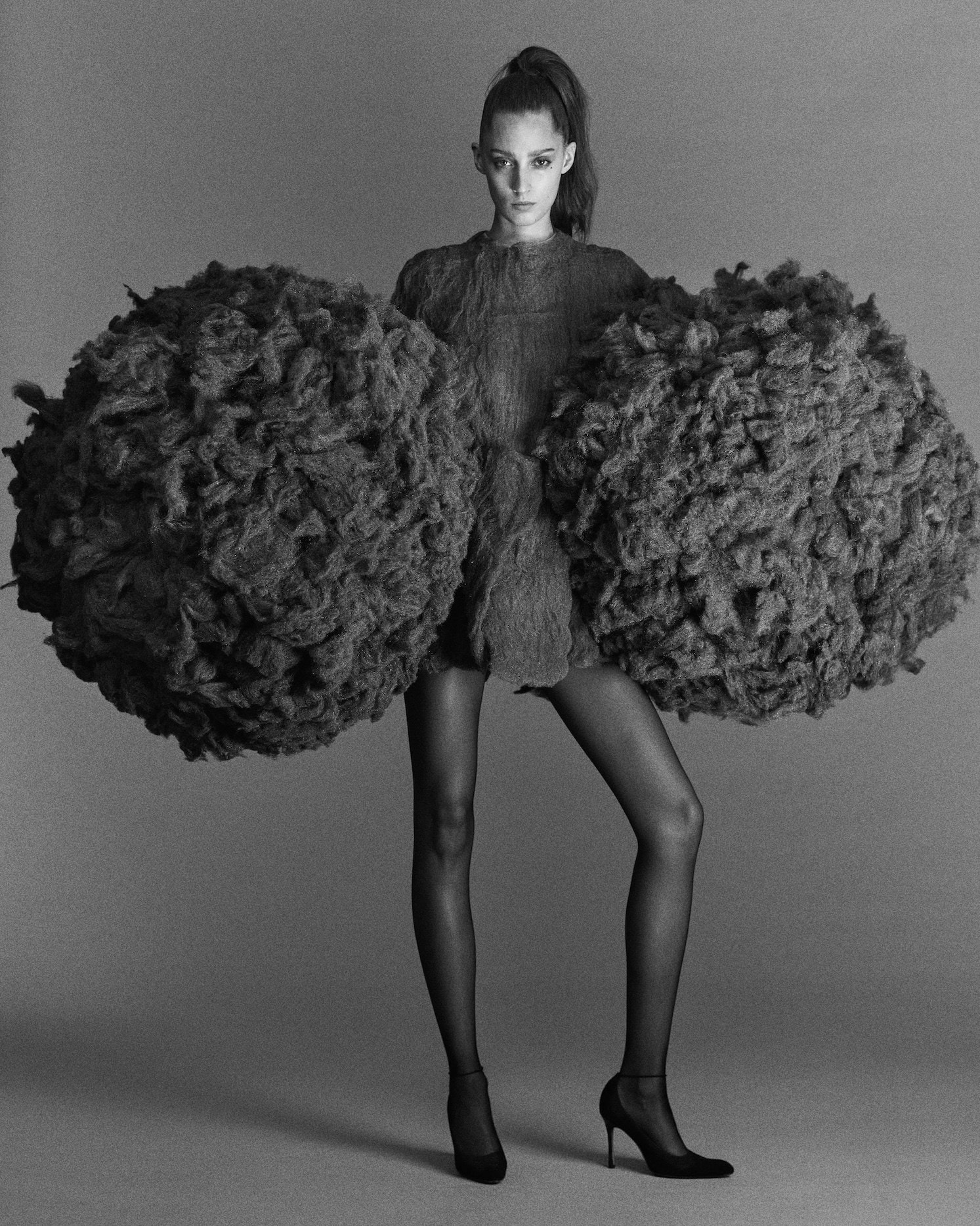

The designer Harry Pontefract makes extraordinary things: in his studio in east London they slump on chairs, where they look a bit of a mess, or hang on an expanse of white wall, where they look a bit like works of art. Both impressions are exaggerated by the abstraction of many of his items. A ballgown of tugged-out lumps of sheep’s wool mounted on tulle, for instance, looks to Pontefract “like a Richter painting”, but on a chair could be an animal’s corpse (it’s not, as it’s made from fleece – “The amount of times people ask, ‘But is it fur?’ It’s not even shearling,” says the designer). Elsewhere, a dress of cascading burgundy plastic grapes, inspired in part by Caravaggio, looks like some kind of mould bubbling out from the plaster behind it. “There’s something super-tacky about them, because they’re what you have in your fruit bowl, but they’re also so decadent – they’re the most beautiful thing,” which is an odd way to describe fake fruit.

Pontefract designs under the label Ponte. “I wanted the name to relate to mine because it’s so personal, without having to literally use my name and be the face of it,” he says. “And friends called me and my brothers and sisters Ponte for short growing up also, come to think of it.” Pontefract is a wonderfully odd designer, and his pieces look simultaneously like things we’ve seen before yet like nothing we’ve seen before.

An example: hanging on that wall there is also a gold suit – actual gold single-breasted jacket, trousers, shirt, tie and shoes – that Pontefract found, appropriated and then hand-gilded with flaking, fragile 24-carat leaf. It makes me think of the heartless Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz, of the nauseating ostentation of Mar-a-Lago’s nouveau-rococo decor, of King Midas and Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger. Hung so the hems of the trousers dangle a few feet from the floor, this suit kind of looks like a Joseph Beuys redone by Jeff Koons for a Las Vegas Strip mall. “Yes, it’s a gold suit, but actually, what’s the most basic kind of suit you can get? That’s not Seventies, not Nineties, not anything. It’s just banal. And then you do something to it,” he allows. Which is very much his operating system – Pontefract takes pieces and transforms them, manipulating, redesigning and re-engineering them.

It’s what he’s always done. As a teenager he adapted his own clothes, sewing jeans and shirts into specific shapes – “all bunched because you didn’t even cut it away inside” – to achieve a specific silhouette. It wasn’t an interest in fashion that motivated him – Pontefract grew up in Sheffield where, he says, he didn’t know fashion was a real job. “Because the word ‘fashion’ then was about trends, which isn’t what fashion is,” he says. “So you think you hate fashion because you don’t want anything to do with that.” Even today, aged 37, he finds it sits uncomfortably with him. “Now I say, ‘I make clothes.’ I would never say, ‘I’m a fashion designer.’” Indeed, although Pontefract studied fashion – first at Westminster, then for his MA at Central Saint Martins – his garments are couched in craft, whether in their fabrication (made, often, from found materials, like surplus army sleeping-bag linings, and old MA-1 jackets) or their form. Twists and manipulations are built in, seen in skirts with integrated jockstraps that hold them at strange angles away from the body.

Those clothes attracted attention early. When Pontefract graduated from Central Saint Martins in 2016, his collection was given the prestigious opening slot in that year’s catwalk show, meaning when you look at images online it’s his clothes that seem to represent the entire graduating year. His garments were made out of old American tan-coloured nylon tights, chopped and sliced and layered in intricate overlays of transparency, clothes that were picked up for retail by Dover Street Market, in a small way. “My mum was sewing the socks for the orders,” he says. “I mean, they were expensive socks.” Amanda Harlech was the first person to buy something – an old tights jacket – a fact of which Pontefract is proud. Yet despite that initial success – a few other shops bought those clothes too – Pontefract went to work for Loewe, under Jonathan Anderson, then creative director. Why, instead of establishing his own brand? “I was walking to school because I had no money for the bus, so that’s why,” he says, deadpan. He also reasoned that Anderson’s curatorial approach to design was sufficiently at odds with his own. “I did think, ‘If I do work for someone, I should work with someone who’s completely different,’” Pontefract says. “And when someone understands your work properly, it’s a warming thing.”

He worked at Loewe for six years but was always making his own clothes alongside. “I had my own studio outside work, where I would just make stuff, even sculptures,” he says. “I just suffer from guilt quite a lot because if I don’t do that … It’s not because I really want to, it’s just because you feel awful if you don’t.” His creative compulsion led him to create a photography book with Adrian Joffe and Comme des Garçons before he founded Ponte in 2023.

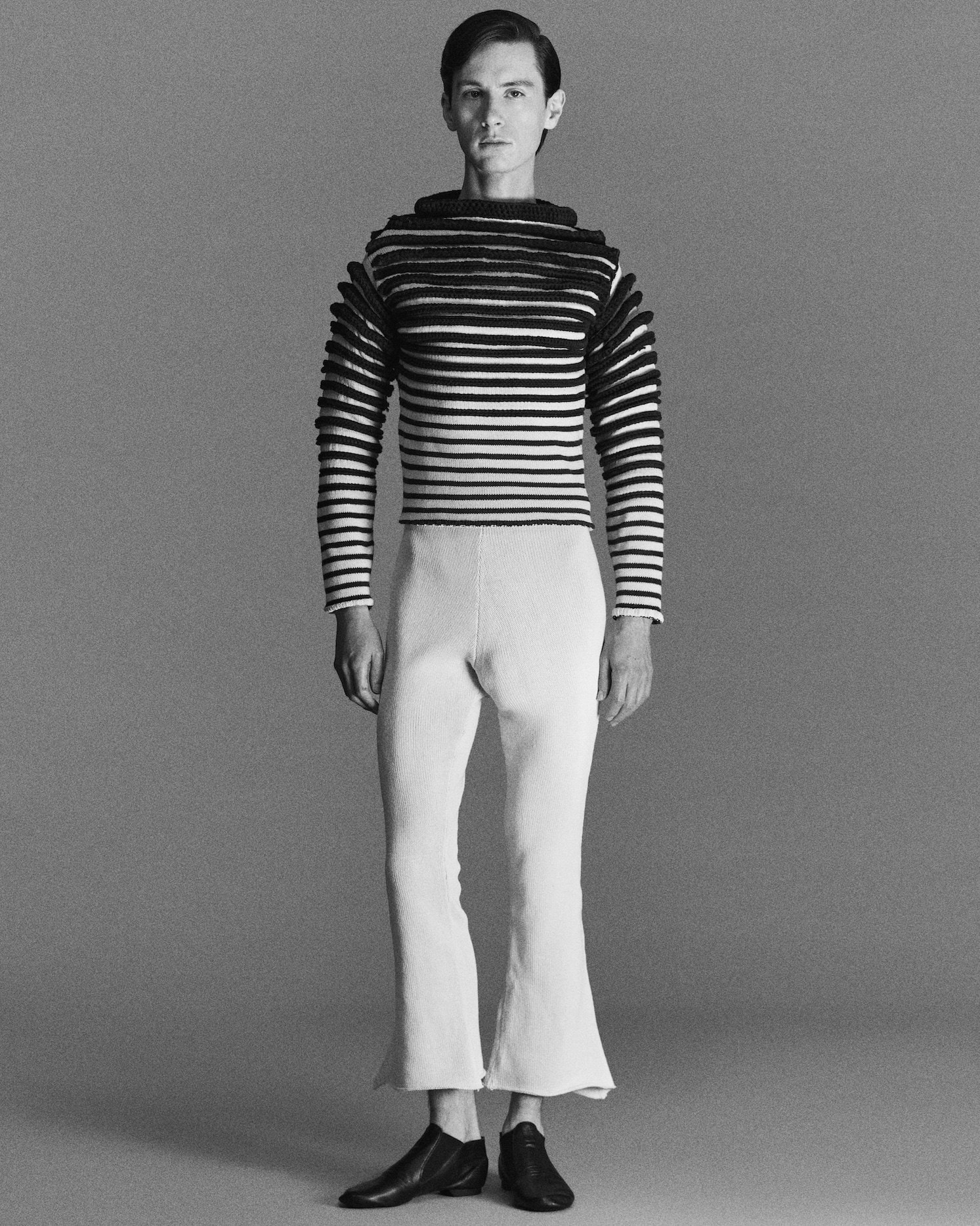

Pontefract is specific, pernickety, precise, geeky. He can name the breed of sheep that provided the wool used to embroider one of his dresses – Leicester longwools, whose shepherdesses he worked with to source the material. He truly believes in these clothes and there’s a meaning behind everything. The latest Ponte collection, for Autumn/Winter 2025, is his fourth. His clothes are intriguing and ambiguous. They’re exciting because they really don’t look like the fashion we’re used to seeing. The garments and their materials are often humdrum – jeans, T-shirts, a conservative little skirt suit cut in pink bridesmaid satin – but their eventual forms feel off, sometimes unsettling. “If it’s trashy, it needs to be the trashiest thing. If it’s banal, it needs to be so banal that it’s interesting,” Pontefract says. That philosophy is possibly the reason major-league talent is excited to collaborate with him for the love of it – the stylist Jane How and photographer Mark Kean worked on Ponte’s last two lookbooks. Even there, he breaks with convention – rather than cobbling together an expensive and potentially unsatisfying show, he opts for quietly releasing collections via stills photography and showroom appointments.

Envisaging his collections not as linear narratives but as collectives of characters, Pontefract creates looks that are highly individualistic, unique and singular, with a deep backstory. “It’s really individual characters. I mean, that’s life, isn’t it?” he says. “It’s a bit like that gold suit. That character’s so tragic for me and it’s not about it being gilded and special. It’s so desperate. I was just thinking of those guys in LA dressed like that, spinning car-wash signs” – apparently, the LA equivalent of the living-statue performers of UK town centres. He shrugs. “It’s really that sort of character.” That also extends to casting, each model specifically tailored to their look. “It’s about what suits the person as well.” Scanning through his clothes, other character descriptions tumble out – even clichés like showgirls. “But it needs to be a weird version of it,” Pontefract says. “Slowly it morphs into something, and it’s not really at all like that decadent showgirl any more. It’s more like a monster.”

Fashion editor: Rebecca Perlmutar. Set design: Alin Bosnoyan. Casting: Lisa Dymph Megens at Industry Art. Models: Jarrod Baddeliyanage at Uns, Elke Biesendorfer, Tiffanie Ibe at Gee Small Faces, Lie Ning, Steph Quinci, Phil Stahl, and Zahra Van Nguyen at Anti-Agency. Photographic assistant: Pierre Lequeux. Styling assistant: Precious Greham. London production: Second Name Agency. Berlin production: Berlin Westend Production GmbH. Berlin executive producer: Nicolas Schwaiger. Berlin producer: Joelle Flacke. Post-production: ArtPost

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageLie Ning is wearing a suit, shirt and tie gilded in 24-carat gold by PONTEPhotography by Larissa Hofmann, Styling by Rebecca Perlmutar

This story is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine:

The designer Harry Pontefract makes extraordinary things: in his studio in east London they slump on chairs, where they look a bit of a mess, or hang on an expanse of white wall, where they look a bit like works of art. Both impressions are exaggerated by the abstraction of many of his items. A ballgown of tugged-out lumps of sheep’s wool mounted on tulle, for instance, looks to Pontefract “like a Richter painting”, but on a chair could be an animal’s corpse (it’s not, as it’s made from fleece – “The amount of times people ask, ‘But is it fur?’ It’s not even shearling,” says the designer). Elsewhere, a dress of cascading burgundy plastic grapes, inspired in part by Caravaggio, looks like some kind of mould bubbling out from the plaster behind it. “There’s something super-tacky about them, because they’re what you have in your fruit bowl, but they’re also so decadent – they’re the most beautiful thing,” which is an odd way to describe fake fruit.

Pontefract designs under the label Ponte. “I wanted the name to relate to mine because it’s so personal, without having to literally use my name and be the face of it,” he says. “And friends called me and my brothers and sisters Ponte for short growing up also, come to think of it.” Pontefract is a wonderfully odd designer, and his pieces look simultaneously like things we’ve seen before yet like nothing we’ve seen before.

An example: hanging on that wall there is also a gold suit – actual gold single-breasted jacket, trousers, shirt, tie and shoes – that Pontefract found, appropriated and then hand-gilded with flaking, fragile 24-carat leaf. It makes me think of the heartless Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz, of the nauseating ostentation of Mar-a-Lago’s nouveau-rococo decor, of King Midas and Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger. Hung so the hems of the trousers dangle a few feet from the floor, this suit kind of looks like a Joseph Beuys redone by Jeff Koons for a Las Vegas Strip mall. “Yes, it’s a gold suit, but actually, what’s the most basic kind of suit you can get? That’s not Seventies, not Nineties, not anything. It’s just banal. And then you do something to it,” he allows. Which is very much his operating system – Pontefract takes pieces and transforms them, manipulating, redesigning and re-engineering them.

It’s what he’s always done. As a teenager he adapted his own clothes, sewing jeans and shirts into specific shapes – “all bunched because you didn’t even cut it away inside” – to achieve a specific silhouette. It wasn’t an interest in fashion that motivated him – Pontefract grew up in Sheffield where, he says, he didn’t know fashion was a real job. “Because the word ‘fashion’ then was about trends, which isn’t what fashion is,” he says. “So you think you hate fashion because you don’t want anything to do with that.” Even today, aged 37, he finds it sits uncomfortably with him. “Now I say, ‘I make clothes.’ I would never say, ‘I’m a fashion designer.’” Indeed, although Pontefract studied fashion – first at Westminster, then for his MA at Central Saint Martins – his garments are couched in craft, whether in their fabrication (made, often, from found materials, like surplus army sleeping-bag linings, and old MA-1 jackets) or their form. Twists and manipulations are built in, seen in skirts with integrated jockstraps that hold them at strange angles away from the body.

Those clothes attracted attention early. When Pontefract graduated from Central Saint Martins in 2016, his collection was given the prestigious opening slot in that year’s catwalk show, meaning when you look at images online it’s his clothes that seem to represent the entire graduating year. His garments were made out of old American tan-coloured nylon tights, chopped and sliced and layered in intricate overlays of transparency, clothes that were picked up for retail by Dover Street Market, in a small way. “My mum was sewing the socks for the orders,” he says. “I mean, they were expensive socks.” Amanda Harlech was the first person to buy something – an old tights jacket – a fact of which Pontefract is proud. Yet despite that initial success – a few other shops bought those clothes too – Pontefract went to work for Loewe, under Jonathan Anderson, then creative director. Why, instead of establishing his own brand? “I was walking to school because I had no money for the bus, so that’s why,” he says, deadpan. He also reasoned that Anderson’s curatorial approach to design was sufficiently at odds with his own. “I did think, ‘If I do work for someone, I should work with someone who’s completely different,’” Pontefract says. “And when someone understands your work properly, it’s a warming thing.”

He worked at Loewe for six years but was always making his own clothes alongside. “I had my own studio outside work, where I would just make stuff, even sculptures,” he says. “I just suffer from guilt quite a lot because if I don’t do that … It’s not because I really want to, it’s just because you feel awful if you don’t.” His creative compulsion led him to create a photography book with Adrian Joffe and Comme des Garçons before he founded Ponte in 2023.

Pontefract is specific, pernickety, precise, geeky. He can name the breed of sheep that provided the wool used to embroider one of his dresses – Leicester longwools, whose shepherdesses he worked with to source the material. He truly believes in these clothes and there’s a meaning behind everything. The latest Ponte collection, for Autumn/Winter 2025, is his fourth. His clothes are intriguing and ambiguous. They’re exciting because they really don’t look like the fashion we’re used to seeing. The garments and their materials are often humdrum – jeans, T-shirts, a conservative little skirt suit cut in pink bridesmaid satin – but their eventual forms feel off, sometimes unsettling. “If it’s trashy, it needs to be the trashiest thing. If it’s banal, it needs to be so banal that it’s interesting,” Pontefract says. That philosophy is possibly the reason major-league talent is excited to collaborate with him for the love of it – the stylist Jane How and photographer Mark Kean worked on Ponte’s last two lookbooks. Even there, he breaks with convention – rather than cobbling together an expensive and potentially unsatisfying show, he opts for quietly releasing collections via stills photography and showroom appointments.

Envisaging his collections not as linear narratives but as collectives of characters, Pontefract creates looks that are highly individualistic, unique and singular, with a deep backstory. “It’s really individual characters. I mean, that’s life, isn’t it?” he says. “It’s a bit like that gold suit. That character’s so tragic for me and it’s not about it being gilded and special. It’s so desperate. I was just thinking of those guys in LA dressed like that, spinning car-wash signs” – apparently, the LA equivalent of the living-statue performers of UK town centres. He shrugs. “It’s really that sort of character.” That also extends to casting, each model specifically tailored to their look. “It’s about what suits the person as well.” Scanning through his clothes, other character descriptions tumble out – even clichés like showgirls. “But it needs to be a weird version of it,” Pontefract says. “Slowly it morphs into something, and it’s not really at all like that decadent showgirl any more. It’s more like a monster.”

Fashion editor: Rebecca Perlmutar. Set design: Alin Bosnoyan. Casting: Lisa Dymph Megens at Industry Art. Models: Jarrod Baddeliyanage at Uns, Elke Biesendorfer, Tiffanie Ibe at Gee Small Faces, Lie Ning, Steph Quinci, Phil Stahl, and Zahra Van Nguyen at Anti-Agency. Photographic assistant: Pierre Lequeux. Styling assistant: Precious Greham. London production: Second Name Agency. Berlin production: Berlin Westend Production GmbH. Berlin executive producer: Nicolas Schwaiger. Berlin producer: Joelle Flacke. Post-production: ArtPost

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.