Rewrite

From Diva to Mauvais Sang, here are our picks from the French filmmaking movement that helped shape the 80s on screen

In 1981, a young Parisian director kickstarted a style of French cinema as synonymous with the decade to come as the Nouvelle Vague was with the 1960s, or poetic realism with the 1930s. The cinema du look was a term coined by critic Raphaël Bassan to describe the work of three young filmmakers – Léos Carax, Luc Besson and Jean-Jacques Beineix – overwhelmingly concerned with matters of style. And Diva was where it all began, Beineix’s noirish story of an opera-obsessed postman (Frédéric Andréi) drawn into a criminal conspiracy.

Released in 1981, Beineix’s film was slated in France but played well abroad, where its lush, rhapsodic style made it a cult favourite. Like many of the films that followed, Diva drew on giallo’s expressive use of colour, action cinema’s rapid cutting style and pop art’s blend of high and low culture, telling a story of young people living on the margins of urban society. It’s a combination that France, ever alert to the lurking threat of Americanisation, was predictably sniffy about. But didn’t Jean-Luc Godard twist the tropes of Hollywood cinema to his own radical ends in the 1960s? Beineix and his peers weren’t out to change the world, but they did know how it felt to live in it, inhabiting philosopher Guy Debord’s realm of signs and signifiers more fully than Godard ever could.

As Diva returns to full splendour with a new 4K restoration, we revisit five key works from the genre.

Jules (Frédéric Andréi) is a young opera addict living in a surreal factory lockup full of luxury car wrecks. He attracts the attention of two shady ‘collectors’ after making a bootleg tape of a famous soprano, Cynthia Hawkins (Frédéric Andréi), who has never allowed her work to be recorded. Things get even worse when he comes into possession of a second tape, implicating the local police chief in a prostitution ring. A game of cat and mouse follows in which it’s possible to glean bits of other, influential directors’ work – Michael Mann, in the soft-velvet nightscapes of a chase scene through the Paris Metro, and Ridley Scott, who must surely have drawn on Thuy Ann Luu’s plastic-trenchcoated Lolita for Daryl Hannah’s android in Blade Runner. The film met with scorn for its obsessive-compulsive colour blocking and overweening art direction, a sin that some traced back to Beineix’s beginnings in (quelle horreur!) advertising. “Advertising has never invented anything except what artists have invented,” said the director, who went on to direct another cinema du look classic, Betty Blue, in 1986. “It appropriated the Beautiful which the cinema of the New Wave had rejected, which makes certain ignorant critics say that beautiful equals advertising. It kidnapped colour, which the cinema no longer violated, so preoccupied was it with being true to life, which makes certain cretinous critics say that colour equals advertising.”

Honestly? It’s a bit of a cheat having this film on the list. Chéreau was an art-world polymath whose highbrow accomplishments make him an odd fit for cinema du look’s lumpen auteurism, and certainly, this queer coming-of-age thriller lays claim to a psychological complexity other entries in the genre can’t get near. But we’ll let it slide, because The Wounded Man is also a story of alienated youth that unfolds amid parts of the urban landscape usually kept hidden – in this case, the rusting innards of a provincial train station turned after-hours cruising ground. Plus, it has a fearless performance from a young Jean-Hugues Anglade, Beatrice Dalle’s love interest in Betty Blue, as gay teenager Henri, who falls obsessively in lust with a violent hustler (Vittorio Mezzogiorno) 10 years his senior. Less exuberant than the other works on this list, there is nonetheless a twisted romanticism at play here expressed through the flashes of colour that cut through the mush-brown world Henri inhabits, a conformist hangover from the 70s.

Hewing closer in style to Hollywood than Beineix and Carax – it’s no surprise he’s the only one of the genre’s major players to enjoy blockbuster success in the US – Besson’s early breakout stars Christopher Lambert as peroxide safecracker Fred, who teams with a gang of outlaws living in the bowels of the Paris Metro. Lambert is fine as the hero, but it’s the underground setting – a recurring motif in the cinema du look – that’s the real star of the show, alongside Isabelle Adjani’s iconic turn as a power-dressing trophy girlfriend who transforms into a post-punk baddie halfway through. Besson has made better films since – The Big Blue, his magnum opus, remains sadly underlooked – but there’s something about the scrappy, underdog charm of Subway that sticks.

A brilliant visual talent and the ‘artiest’ of the genre’s three leading lights, Carax brings uncut essence du look with his second feature, which helped launch the careers of Denis Lavant, Juliette Binoche and Julie Delpy. In a Paris of the near future where people having sex without love succumb to a mysterious disease – err, OK – two ageing crims are coerced into stealing the antidote. To do so, they recruit pouting teenager Alex (Lavant), the son of a late accomplice who is said to have ‘magician’s hands’. Carax sketches his plot through quick, expressive cuts and a heightened red, yellow and blue colour scheme before abandoning it completely in favour of the blossoming love story between Alex and Anna (Binoche), his boss’s much-younger girlfriend. Much florid dialogue ensues – “Every morning, concrete in my gut… I long for the kiss of speed” – but so do moments of sheer visual transcendence, like the parachute embrace and the now-iconic scene of Lavant bolting down the street to the strains of David Bowie’s Modern Love.

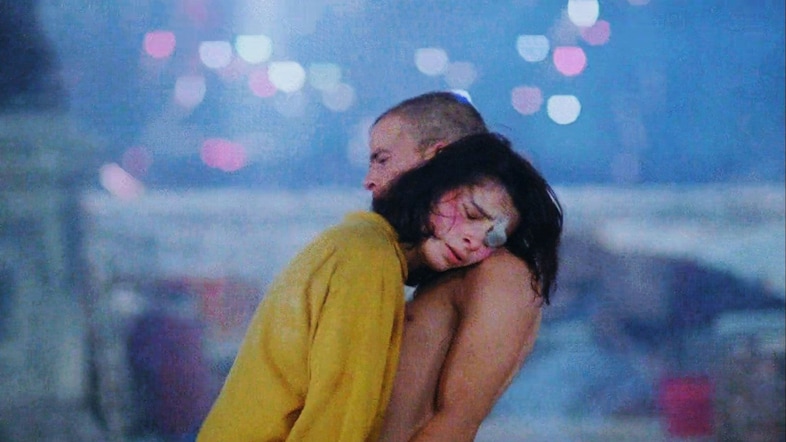

The cinema du look reached its apotheosis with Carax’s stunning, £20m folly, whose troubled production make it something akin to the French Apocalypse Now. Reteaming his leads on Mauvais Sang for a tale of two lost souls living on Paris’s oldest bridge, Carax casts Dennis Lavant as Alex, an alcoholic street performer who falls for painter Anna (Juliette Binoche), who is losing her eyesight to a rare disease. Again, mainstream Hollywood’s visual grammar – Fast cuts! Explosions! Guns! – is subverted through a story told in wild, expressive strokes, including a drunken carouse under fireworks that sees the pair go for a jet-ski ride on the Seine (Binoche nearly drowned during filming). The film recouped only a fraction of its costs, effectively bringing the curtain down on the genre as Carax and Beineix, after his follow-up to Betty Blue tanked at the box office, tended to their wounds and Besson went to Hollywood.

Diva is out now via Studio Canal on 4K UHD and Blu-Ray.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

From Diva to Mauvais Sang, here are our picks from the French filmmaking movement that helped shape the 80s on screen

In 1981, a young Parisian director kickstarted a style of French cinema as synonymous with the decade to come as the Nouvelle Vague was with the 1960s, or poetic realism with the 1930s. The cinema du look was a term coined by critic Raphaël Bassan to describe the work of three young filmmakers – Léos Carax, Luc Besson and Jean-Jacques Beineix – overwhelmingly concerned with matters of style. And Diva was where it all began, Beineix’s noirish story of an opera-obsessed postman (Frédéric Andréi) drawn into a criminal conspiracy.

Released in 1981, Beineix’s film was slated in France but played well abroad, where its lush, rhapsodic style made it a cult favourite. Like many of the films that followed, Diva drew on giallo’s expressive use of colour, action cinema’s rapid cutting style and pop art’s blend of high and low culture, telling a story of young people living on the margins of urban society. It’s a combination that France, ever alert to the lurking threat of Americanisation, was predictably sniffy about. But didn’t Jean-Luc Godard twist the tropes of Hollywood cinema to his own radical ends in the 1960s? Beineix and his peers weren’t out to change the world, but they did know how it felt to live in it, inhabiting philosopher Guy Debord’s realm of signs and signifiers more fully than Godard ever could.

As Diva returns to full splendour with a new 4K restoration, we revisit five key works from the genre.

Jules (Frédéric Andréi) is a young opera addict living in a surreal factory lockup full of luxury car wrecks. He attracts the attention of two shady ‘collectors’ after making a bootleg tape of a famous soprano, Cynthia Hawkins (Frédéric Andréi), who has never allowed her work to be recorded. Things get even worse when he comes into possession of a second tape, implicating the local police chief in a prostitution ring. A game of cat and mouse follows in which it’s possible to glean bits of other, influential directors’ work – Michael Mann, in the soft-velvet nightscapes of a chase scene through the Paris Metro, and Ridley Scott, who must surely have drawn on Thuy Ann Luu’s plastic-trenchcoated Lolita for Daryl Hannah’s android in Blade Runner. The film met with scorn for its obsessive-compulsive colour blocking and overweening art direction, a sin that some traced back to Beineix’s beginnings in (quelle horreur!) advertising. “Advertising has never invented anything except what artists have invented,” said the director, who went on to direct another cinema du look classic, Betty Blue, in 1986. “It appropriated the Beautiful which the cinema of the New Wave had rejected, which makes certain ignorant critics say that beautiful equals advertising. It kidnapped colour, which the cinema no longer violated, so preoccupied was it with being true to life, which makes certain cretinous critics say that colour equals advertising.”

Honestly? It’s a bit of a cheat having this film on the list. Chéreau was an art-world polymath whose highbrow accomplishments make him an odd fit for cinema du look’s lumpen auteurism, and certainly, this queer coming-of-age thriller lays claim to a psychological complexity other entries in the genre can’t get near. But we’ll let it slide, because The Wounded Man is also a story of alienated youth that unfolds amid parts of the urban landscape usually kept hidden – in this case, the rusting innards of a provincial train station turned after-hours cruising ground. Plus, it has a fearless performance from a young Jean-Hugues Anglade, Beatrice Dalle’s love interest in Betty Blue, as gay teenager Henri, who falls obsessively in lust with a violent hustler (Vittorio Mezzogiorno) 10 years his senior. Less exuberant than the other works on this list, there is nonetheless a twisted romanticism at play here expressed through the flashes of colour that cut through the mush-brown world Henri inhabits, a conformist hangover from the 70s.

Hewing closer in style to Hollywood than Beineix and Carax – it’s no surprise he’s the only one of the genre’s major players to enjoy blockbuster success in the US – Besson’s early breakout stars Christopher Lambert as peroxide safecracker Fred, who teams with a gang of outlaws living in the bowels of the Paris Metro. Lambert is fine as the hero, but it’s the underground setting – a recurring motif in the cinema du look – that’s the real star of the show, alongside Isabelle Adjani’s iconic turn as a power-dressing trophy girlfriend who transforms into a post-punk baddie halfway through. Besson has made better films since – The Big Blue, his magnum opus, remains sadly underlooked – but there’s something about the scrappy, underdog charm of Subway that sticks.

A brilliant visual talent and the ‘artiest’ of the genre’s three leading lights, Carax brings uncut essence du look with his second feature, which helped launch the careers of Denis Lavant, Juliette Binoche and Julie Delpy. In a Paris of the near future where people having sex without love succumb to a mysterious disease – err, OK – two ageing crims are coerced into stealing the antidote. To do so, they recruit pouting teenager Alex (Lavant), the son of a late accomplice who is said to have ‘magician’s hands’. Carax sketches his plot through quick, expressive cuts and a heightened red, yellow and blue colour scheme before abandoning it completely in favour of the blossoming love story between Alex and Anna (Binoche), his boss’s much-younger girlfriend. Much florid dialogue ensues – “Every morning, concrete in my gut… I long for the kiss of speed” – but so do moments of sheer visual transcendence, like the parachute embrace and the now-iconic scene of Lavant bolting down the street to the strains of David Bowie’s Modern Love.

The cinema du look reached its apotheosis with Carax’s stunning, £20m folly, whose troubled production make it something akin to the French Apocalypse Now. Reteaming his leads on Mauvais Sang for a tale of two lost souls living on Paris’s oldest bridge, Carax casts Dennis Lavant as Alex, an alcoholic street performer who falls for painter Anna (Juliette Binoche), who is losing her eyesight to a rare disease. Again, mainstream Hollywood’s visual grammar – Fast cuts! Explosions! Guns! – is subverted through a story told in wild, expressive strokes, including a drunken carouse under fireworks that sees the pair go for a jet-ski ride on the Seine (Binoche nearly drowned during filming). The film recouped only a fraction of its costs, effectively bringing the curtain down on the genre as Carax and Beineix, after his follow-up to Betty Blue tanked at the box office, tended to their wounds and Besson went to Hollywood.

Diva is out now via Studio Canal on 4K UHD and Blu-Ray.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.