Rewrite

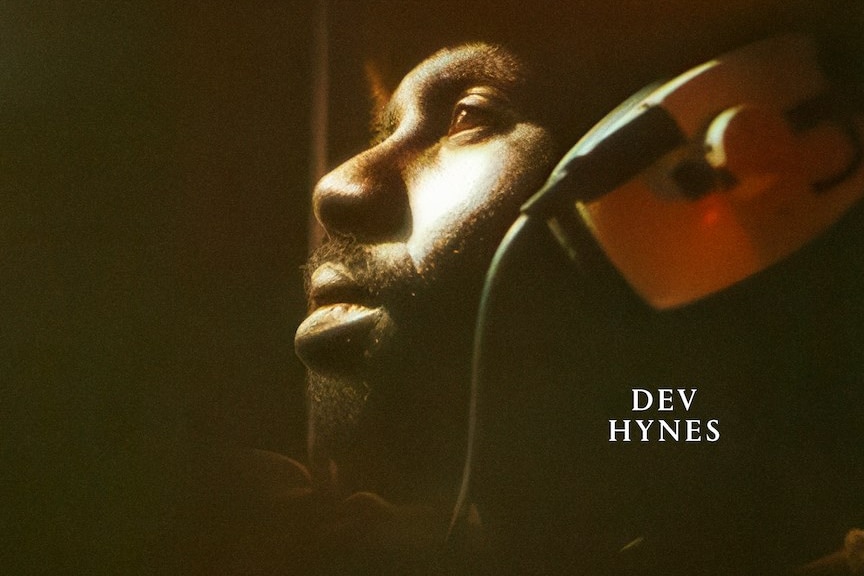

Lead ImageDev is wearing a T-shirt in suede by MARTINE ROSE. Hat in faux fur from THE CONTEMPORARY WARDROBE COLLECTION

This story is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine:

June is dying and it’s hot in New York City: Greenwich Village sounds like coughing saxophones and bleating car horns, laughter drifting off fire escapes, basketballs kissing pavement, a window yawning wide and a mother calling down to her son on his bicycle.

Which is to say, it sounds a bit like a Blood Orange song – balmy, layered with voices, thick with the poetry of urban life. Or it’s a bit like how a Blood Orange song used to sound. These days the music feels more pastoral somehow. More open and orchestral. Gloomier too, and occasionally ecstatic. “Age appropriate,” says Devonté Hynes, who turns 40 in December. And perhaps not so much like New York City, his muse and lover of nearly 20 years.

Since 2011, Hynes has been crafting his wistful, timeless pop songs as Blood Orange, songs that feel cosmopolitan and fluid and, often, like a long embrace. Music to listen to from a supine position on your bedroom floor, remembering a place you’ve never been to. Music that he has made largely from his own bedroom since he was at secondary school, because he prefers that to the traditional studio set-up. He has made film scores (Palo Alto, Passing); TV soundtracks (We Are Who We Are, In Treatment); dance-punk songs (as part of Test Icicles); country-rock songs (as the solo artist Lightspeed Champion); songs for other people (Sky Ferreira, Solange, FKA twigs, Mariah Carey); classical symphonies (accompanied by orchestras in London, Toronto and Sydney); and dreamlike, heartbreaking songs that combine field recordings, the many instruments he can play (guitar, cello, bass, drums, piano, synths), the voices of his own friends and that undeniably sweet, Prince-like voice. Because he’s always widening his frame, it is difficult to identify any fixed musical signature, but you know a Blood Orange song when you hear it, even if it was gifted to somebody else.

“Dev’s one of those artists who everyone tries to imitate, consciously or unconsciously,” says his friend Lorde, who met him when she moved to New York City in the summer of 2021. She features on his new album, Essex Honey; he contributed to her latest project, Virgin. “It’s beautiful to me, but none get close to what he does.” Lorde first discovered Hynes at 14 years old, when she heard Solange’s Losing You playing from a stereo in somebody’s backyard in Auckland and followed the paper trail to his solo work. “It was distinct for its quality but felt like it had always been there,” she says. “Dev’s music is unmistakably him – subtle, sexy, infectious, rhythmic, many-voiced. It sounded like what I hoped adulthood was like, if you moved to a city and met the right people. And it’s ageing the best out of any modern pop, I think. It all sounds so good and effortless.”

Hynes strolls into the crowded Brazilian café in Greenwich Village where we’ve arranged to meet just after 3pm dressed in dark shorts, trainers and a Tottenham Hotspur jersey that recalls his lapsed-jock status. His thin, over-ear headphones, which he seems to go nowhere without, are blasting a master playlist he’s compiled of songs by Beach House (he wishes he’d found the title Depression Cherry first) and he has a book of interviews with the Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke tucked under his arm. “I think people are surprised when I say he’s one of my favourite directors,” says Hynes, who studied film and literature during sixth form.

Admittedly I count myself among the surprised. Hynes is a lean, mild-mannered Brit. He has the sort of open face that would invite strangers to ask for directions. He speaks softly; he sings in a high falsetto. His friends describe him in a language that verges on reverence: “If I hadn’t met him, I’d have had to make him up,” says the novelist Zadie Smith, who refers to him as a brother. The pair met in 2016, when Smith was teaching creative writing at NYU and President Trump had just been elected. “Dev to me was a light who made New York feel like somewhere good things could still happen.”

I’m positive, for my part, that it’s ridiculous to make judgements about someone’s worldview by an analysis of their disposition, but here I am, pointlessly trying to reconcile this gentle, elegant person with his love for Haneke, a man who leaves music out of all his movies and whose work feels intended to make his audience squirm. It seems incongruous with Hynes’s impressionistic, empathic songwriting, his affinity for the bohemian character of 1980s New York and those sumptuous tableaux from his often self-directed music videos.

But film is an integral element of his language; there is the sense that he’s a kind of frustrated filmmaker. “He’ll run from a camera, out of shyness,” says Ian Isiah, a longtime friend and frequent collaborator. “But he’s a genius behind one – directing, composing, writing.” Songs like Sutphin Boulevard, about a young boy who dresses in drag, scan like scenes from movies Hynes has directed in his mind. And Haneke’s Funny Games is on the syllabus of artworks to understand him. (Also on the syllabus: Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, Arthur Russell’s Calling Out of Context, William Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, and a YouTube video of Spurs highlights in the semifinal against Ajax in the 2019 Uefa Champions League.) Maybe his music can feel hopeful because its author is, by his own admission, “pessimistic and nihilistic”, and so it’s a means of self-soothing at the end of the world. “Haneke always assumes, which I also assume, that the audience is intelligent and that they’re going to understand the text,” Hynes says. We agree that Haneke, unlike most American filmmakers, recognises that violence is not at all spectacular, and that it’s rare to feel some existential crescendo towards any traumatic event that upends your life: tragedy happens because life does, and maybe there’s no reason at all for it. “It’s filmmaking that’s asking questions, but there’s no easy answer to them,” Hynes says. “It’s more of an exploration of a particular question, and I think I work in a similar way.”

“I’ve literally never written a song that wasn’t about myself. The only reason I make music is excavation, you know? To work through things” – Dev Hynes

In his music, Hynes favours diagnosis over prescription. His songs search and meander but rarely land anywhere concrete. His stories are troubled by whatever troubles him, whether they’re love songs or songs written from the perspective of women, as many of those on Coastal Grooves, his debut studio album as Blood Orange, are. “I’ve literally never written a song that wasn’t about myself,” he says. “The only reason I make music is excavation, you know? To work through things. I’m always thinking about the past.” You could say that Cupid Deluxe, the follow-up to Coastal Grooves, was a study of emotional transitions; that Freetown Sound was an interrogation of selfhood by way of the communal; that Negro Swan was a meditation on belonging, rejection and the meaning of family. “I think, when people get angry at films and art, it’s because they’re not being let off easy,” he says when I describe an experience I had with Haneke’s The Piano Teacher. “There’s no easy answer. It’s frustrating, because it’s like, what’s happening? Why am I watching this? Why am I feeling this way?”

Essex Honey offers no sweet or easy answers. It is, instead, sublimely melancholic. The cello abounds, plaintively and inquisitively. Voices echo, delay and reverberate. Percussion is unstable, prone to shifting mid-song and introducing jazzy drum improvisations or pulsing breakbeats. Grief-stricken images emerge like lily pads in a stream: broken, flickering lights; tight muscles; “knitted” hearts; swirling drains and dusky room corners; the floor, maybe the whole Earth, vanishing from beneath you. Hynes’s mother died suddenly in 2023, and many of these songs are an inventory of his attempts to reorientate himself in the world in the aftermath. “No, I can’t pretend I know everything ends / I just want to see again,” he sings on Somewhere in Between, over syncopated guitar licks and a faraway harmonica. Hynes is no stranger to exploring his own pain in his art, or to connecting that pain, tenderly illuminated, to broader political struggles. But where his writing could at times be heavy with metaphor and character-building, here he is in his clearest, most unadorned register. Essex Honey, his first album in seven years, seems to be asking: how do you move forward, how can you start the day or wash your hands or create music, when it feels like everything has gone to shit? He doesn’t bother to answer the question. Or, there is no answer. There is only the bed to make, the dishes to clean, the laundry to be done, the pigeons crowding around the spikes on the windowsill. There is only the next morning.

Here is how he would tell it, how he has always told it: Hynes never “moved” to New York. There was no decision or reason to come to New York, which, in the grand scheme of things, seems reason enough. Why does anybody move anywhere anyway? To see if they’ll be different maybe. To see if there’s a cure for loneliness.

Hynes was born and raised in Ilford, a town in a part of east London that’s considered to be Essex and known mostly for its association with a manufacturer of black and white photographic materials. His dad, who was born in Sierra Leone, was the manager of a department store, and his Guyanese mother was a healthcare consultant who counselled teen mothers. He is the youngest of three siblings and spent most of his childhood alone in his bedroom, which he decorated with various posters: Smashing Pumpkins, Slipknot, David Beckham. In his dark sanctuary, he could practise the cello, or tape songs off the radio, and escape the bullying he incurred from the neighbourhood boy racers: the name-calling, being spat on during bus rides, getting jumped and occasionally hospitalised. (One time, he told Sam Fragoso on the podcast Talk Easy, he was beaten so badly that his mother enrolled him in karate lessons.) He had an ear for classical music and a bottomless appreciation for Bach but was seduced by the fast-paced Ministry of Sound CDs that his older sister, Louise, a “big rave listener”, liked to collect, and when he was older she sometimes took him to the parties. “Essex has this very rich musical history that no one knows about, because people in Essex don’t really care,” Hynes says. Many of the EDM soundscapes he heard at Ministry – Underworld, the Prodigy, Stereolab – form the spine of Essex Honey, with the splashes of drum’n’bass that feel genuinely new in the Blood Orange discography. It’s perhaps his first album that feels distinctly like London.

Hynes’s career-launching band, like his eventual relocation to America, was a byproduct of accident and circumstance. He was 18 or 19 and addicted to playing in short-lived punk bands. One such group, then called Balls, was slated to support the Unicorns for a show in Nottingham, but one of the bandmates, the visual artist Ferry Gouw, had to return to Indonesia to renew his visa. Gouw told the club promoter that Balls couldn’t play the show but that his friends’ band, Test Icicles, could replace them. But the band did not exist. So the other former members of Balls, Sam Mehran and Rory Attwell, wrote some songs with Hynes, who played the guitar, keyboard and sang, and they played the show under that new name.

The jagged, freaked-out music that Test Icicles made together, central to the new rave movement of the mid-2000s, is a far cry from the slick, jazz-funk-tinged R&B of today’s Blood Orange. They had no bassist and used a drum machine in lieu of an actual drummer – and got booed at a lot of their early shows because of it. “The UK trio is hard, fast and viciously catchy, but above all scary,” reads a Pitchfork review of For Screening Purposes Only, the sole album Test Icicles recorded. “Guitars don’t chug and wail; they whinny and scream.” A one-star show review in The Guardian from 2005 balks at a previous live set from the band, during which 1) Attwell broke his nose stage-diving, 2) Mehran was launched down a staircase by a security guard, and 3) Hynes “severed his big toe on a broken bottle and passed out at his keyboard”. In short, it was weird, it was metal, it was one influence for Charli xcx’s Brat, that imperious 2024 declaration of club dominance that turned everything green for a summer.

The band broke up in 2006. They were meant to do an American tour and had all secured their visas to travel, but they cancelled their shows. Suddenly the world Hynes had read about in Please Kill Me, a punk history of New York City, seemed like a plausible destination. He was already couch-surfing with a backpack in London, and because he knew someone who knew someone with their own couch in Long Island City, that was where he went. In America, his music changed. He recorded some folksy, orchestral country-pop songs in Omaha, Nebraska – home of the famed record label Saddle Creek – under the name Lightspeed Champion. That project, written with and produced by Bright Eyes’ Mike Mogis, abandoned the abrasive, dance-punk sound of Test Icicles and replaced it with lush strings and spare atmospherics. It sounded, according to Hynes, then 22, like “losing your virginity for the fifth time”. Two albums and three years later, Hynes had reinvented himself again. He had tweaked his sound to make “songs that could be sung by a drag queen”. He had a new name. And the first line he sang as Blood Orange, over the spunky, muted guitar riffs of Forget It, announced his evolution: “I feel unique / Not yet complete.”

Because he makes music compulsively, and because it’s the primary outlet he uses to work through his emotions, Hynes has always conceived of his albums as time capsules of his inner life. He likes how Adele titles her records after the ages when the living that produced the album happened: 19, 21, 25, 30. You could do the same to make sense of some of his work, as a sort of mental exercise – Essex Honey becomes 37 or 38 or 39, Negro Swan is retitled 32 or 33, Freetown Sound comprises 30 or 31, and so on. He made Cupid Deluxe, for example, when he was 26 and 27, just as New York was beginning to feel like home to him, which was also, unfortunately, the year his East Village apartment burned down and everything he owned went up in flames: clothes, hard drives, sentimental items, music, his puppy, Cupid. Accordingly, the album fixates on states of in-betweenness: situationships, subway rides, decisions yet unmade.

“Explaining this can sound a little … I don’t know,” Hynes says sheepishly. “But it’s very easy for me to make music. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to be music I think is good, or music that I like or think speaks to where I am, but the actual ability to create it is, I find, extremely easy.”

Still, it’s been six years since the last full-length Blood Orange project: 2019’s Angel’s Pulse – the only mixtape in his catalogue, distinctly looser and less precious than his usual recordings, like a master painter revealing their sketches or a filmmaker exhibiting first drafts of a screenplay. It’s not as if there’s been no music since then. It’s just that much of it, aside from the Four Songs EP he released in 2022, has been made for others: operatic works for Marni, classical ones composed or performed for orchestras, scores for the directors Paul Schrader and Melina Matsoukas. This constant stream of wordless classical music has allowed his mind to wander back through his memories and to contend with the turmoil of the world outside.

“It’s very easy for me to make music. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to be music I think is good, or music that I like or think speaks to where I am, but the actual ability to create it is, I find, extremely easy” – Dev Hynes

A lot of life has happened in that six-year interim, a lot of grief to be accounted for. A global pandemic. Genocides in Sudan and Tigray and Gaza. Assaults on trans people in America and the UK. Rampant xenophobia and the hyperactivity of immigration enforcement officers across the US. “I think the thing that was stopping me from going all the way in was that I was really struggling to find the why – like, why should this album even exist?” Hynes says. There were things happening in his life, and he was always writing, but he couldn’t marshal his energy towards making a coherent project because life itself was not coherent. He felt moored, indelibly, to the past. The dam broke one morning in 2023, when he was pacing around his Greenwich Village apartment, allowing Spotify to select music he might like, and a song came on that felt telegraphed from inside his own head. It was Sufjan Stevens’s Fourth of July, from his 2015 album Carrie & Lowell, a collection of sparse, downtempo folk songs that narrate the death of the musician’s mother from stomach cancer.

“I had just lost my mother, and Sufjan’s mother had passed away, and the description was eerily similar to how I was feeling,” Hynes says. “It sounds so simple, but in that moment I was like, oh, I need to get over myself.” It suddenly felt ridiculous, even offensive, that he had the ability to make music people wanted to hear and that, in his mourning, he was withholding it. He told the poet, singer-songwriter and filmmaker Mustafa about discovering the song while they were hanging out together in Paris, how he couldn’t stop hearing it everywhere, and they bonded over their shared love for it. “It opened this conversation for us about music and the way it impacts us, how it could sometimes free us from our isolation,” says Mustafa, who writes often about grief, memory and dispossession; his baritone voice emerges throughout Essex Honey. “It reminded him of why music is made at all.”

“I started thinking back to when I was younger, just making music for fun and playing in bands in London or whatever,” Hynes says. The thought freed him up. “And so that moment really did change how I thought. Even with live shows. I’ve always had this weird relationship to them and wouldn’t do too many, but I started thinking about how insane it was that I could do it and it started feeling like I needed to honour it.”

And so the music changed again. Some of the songs on Essex Honey, to be fair, are old; Life, with Tirzah and Charlotte Dos Santos, was made 12 years ago, and most of the arrangement hasn’t been touched except for some tweaks on the bass guitar. But where previous Blood Orange albums have been largely city-centric, this one can sound almost rural, like he took a sabbatical in the UK countryside and emerged anew, with new questions. His voice, which he used to hate, is still surrounded by others, but there are more songs here with just Hynes than anything since Coastal Grooves. “I think I’d lived so long in America that, subconsciously, I knew I wanted to bring it back to England,” he says. “So I just started spending more time there, in England and other parts of Europe, and, naturally, the music started happening.” Many of the songs became shaded by the music that he grew up on, and so we get samples of the Durutti Column and interpolations of Elliott Smith, or classical compositions that explode midway through and veer sharply from the concert hall to the club.

“I’ve loved observing the evolution of his music,” says the musician Liam Benzvi, a frequent collaborator who sings background on Essex Honey. “He really tries to create these vast sonic landscapes now and keeps making things get bigger and bigger.” Benzvi remembers first hearing Coastal Grooves when he was at college in Minneapolis, nursing an obsession with Prince and the Replacements. “No one was really using drum machines the way he was, in this non-electroclashy way,” he says. “These weren’t hard, abrasive sounds. They were delicate drum machine sounds. And probably the last person to do that was Kanye, on 808s & Heartbreak. But I loved how soft it was, and how pretty [Hynes’s] voice was, and how you never knew where his guitar was going to go.”

Hynes himself recognises how the music has evolved. “I think that, now, I want to be so clear,” he says. Death, after all, is the least abstract condition, and its appearance in his life has made him cleave to solidity and directness. “Some of my biggest lyrical references, like Morrissey, have a way with these really blunt sentences – ‘I was looking for a job, and then I found a job,’” he says. His new album is replete with that cadence. “I don’t want to be here any more,” he sings plainly on Thinking Clean, which collides a wild, jazzy drum break with a four-on–the-floor house beat. “I wash my hands and stare into the drain,” on The Last of England. Some sentences repeat, gradually accumulating severity, coalescing into theses. “Hard to look at you,” he sings on Look at You, a line that returns two tracks later. “I just want to see again,” he sings over and over on Somewhere in Between. Certain cello passages, provided by the Danish cellist Cæcille Trier and reworked, apparently beyond her recognition, by Hynes, recur like overtures or flashbacks. “I wanted it to feel like someone remembering songs, or moments, or situations,” he says. “Maybe that little situation is a little wart in your head, but it’s different in reality. Maybe now it feels sweeter than it was before. Or maybe it’s worse than that. But I wanted it to feel like a memory package.”

In Grand Union, a 2019 collection of short stories by Zadie Smith, there’s a scene inspired by a “religious experience” she had at a Blood Orange concert in New York. The protagonist, a 77-year-old woman called Wendy English, has been reflecting on her life, and her disappeared sister, and she arrives at a show in Central Park that makes her feel as if her ears, everyone’s ears, are connected to their souls. “Historically speaking,” she thinks, “men with guitars have held their instruments in a certain way and pointed them at you like a penis and stood in the centre of whatever space and drawn all energy to them like a lightning rod stuck on a church spire. He didn’t do any of that. For most of the show we had no idea where he was, really: he kept hiding behind other people, other instruments. He had his locks tied in a bun and wore some very high-waisted, salmon-coloured trousers. Meanwhile, the crowd was filled with every type of true self imaginable in the tristate area.”

In some ways, this observation about that “hiding” articulates the centrifugal instinct at the heart of Hynes’s music as Blood Orange. “Dev never does anything alone,” Isiah says. “He understands that community is really important. At any point, in any country, in any hotel room, this man has a laptop up in a makeshift studio, jamming alone, and then adding you to a group text like, ‘Hey, meet me here, I need you to come now.’” Hynes is never precious about being the primary focus of anything at all. “He’s been so good at parting from authorship, in a time when so much of being an artist is about building borders around that authorship,” Mustafa says. Hynes’s albums, his live shows, are a tapestry of voices. The voices belong to other people – Caroline Polachek, Eva Tolkin, Ian Isiah, Adam Bainbridge, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Carly Rae Jepsen, Mustafa, Janet Mock, the list goes on – but they’re also, somehow, his own. Perhaps this deference is a vestige of self-belief, the knowledge that your voice is clear enough to be heard even when you’ve said nothing at all, even when you’ve got someone else to say it for you. On those perfect, early pop songs he wrote for other artists – Sky Ferreira’s Everything Is Embarrassing, for example, or the songs from Solange’s True EP – you can almost hear his demo, that silken, feminine voice, cutting through the mix. “I’ve never really felt a connection to performing my own music,” says Hynes, who famously has disliked touring. “But I love performing other people’s music. Doing classical recitals or playing in other people’s bands. I think it’s because, in my head, Blood Orange exists as a recording project for myself.” (He promises he’s excited to tour the album this autumn: he has finally arrived at a place where he knows how to enjoy playing his own music live.)

It is rare for an auteur to be so yielding. He tends to inspire acts of creation in others; because of him, Isiah has started producing songs, scoring, making treatments and jingles, and calling in his friends to make music. In 2022, Benzvi joined Hynes on stage when Blood Orange was opening for a 15-night Harry Styles residency at Madison Square Garden in Manhattan. Hynes encouraged him to play songs from his debut album, Acts of Service, which had come out earlier that year. “He would let me do that, like, five times, in front of this crowd of screaming girls that were there every single night because they’d bought tickets for the entire residency,” Benzvi says. “And they would just know what was coming, when it was coming. So they would be chanting his name, then chanting my name – it was so weird and surreal.” The pair now support each other on their respective records. Hynes is also featured on the single Other Guys, from Benzvi’s 2024 sophomore album, … And His Splash Band, and appeared in the song’s video.

In some ways, the approach Hynes takes to collaboration resembles the hodgepodge formation of Test Icicles: whoever is around is at risk of being pulled into his orbit. “It’s kind of always been like that,” he admits. “If you’re around me when I’m in one of those phases, and they are like phases, where I’m really working on it, you’re gonna be involved, whether you’re a musician or not. Because if you’re there, you’re a friend of mine, and I trust you. And I actually prefer it if you can’t play music – those are the opinions I genuinely listen to.” He works like a maestro, conducting a symphony he wrote all the parts for.

“I’ve never really felt a connection to performing my own music. But I love performing other people’s music” – Dev Hynes

Smith, for example, has a guest slot singing a few lines on a song from Essex Honey. She’d gone over to his new place and it was set up like a studio, and she improvised over something purely because he needed a voice to fill a gap. She didn’t expect to be on the record. She’d earned money as a cabaret singer when she was a student at King’s College, Cambridge, but for the most part, she sings at home. “He makes a space in which you feel free and don’t need to be ashamed. For me, singing was always very attached to shame – I have a lot of excellent musicians in my family, a few of them world-class musicians, and I always judged myself against that standard and thought I could never be enough,” she tells me. “But Dev helped me realise that I have a really adolescent way of thinking about singing. I imagined you had to sing like Stevie Wonder or just not do it at all. I don’t get the impression Dev is ever after perfection. He’s always looking for something human and real.”

Lorde feels similarly. “With Dev, everything is up for grabs and anyone’s idea could be the best,” she tells me. “I love watching Dev work – picking up instruments on a whim, no judgement, just letting it come out of him, sometimes surprising himself. I love how he uses vocalists like paint colours, the combination of voices he’s returned to over and over, and new ones who sing just a line or two. But I think it’s Dev singing the whole time, using other bodies to get the colours he wants.” He taught her what true collaboration looks like, that sharing the floor is always to your advantage. “If you’re around long enough and he loves you, you’ll be on the record. It has the effect of feeling like real life encapsulated in music, which is difficult to do,” she says. “He’s always a step ahead, adding something totally surprising but unmistakably him, there in his studio with the projector playing a film, bent over an instrument, smiling, humming to himself.”

Hair: Soichi Inagaki at MA+Talent using BUMBLE AND BUMBLE. Make-up: Crystabel Efemena Riley at Julian Watson Agency using MÁDARA. Set design: Tilly Power at The Magnet Agency. Photographic assistants: Ed Bourmier and Daiki Nakajima. Styling assistants: Bella Kavanagh and Myles Mansfield. Tailor: Felix Gumbsch. Set-design assistant: Sean Kirwin. Production: REPRO. Executive producer: Rachael Evans. Senior producer: Zuzana Kostolanska. Production assistants: Meron Ayele and Valentyn Korolkov

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine, on sale internationally on 25 September 2025. Pre-order here.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageDev is wearing a T-shirt in suede by MARTINE ROSE. Hat in faux fur from THE CONTEMPORARY WARDROBE COLLECTION

This story is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine:

June is dying and it’s hot in New York City: Greenwich Village sounds like coughing saxophones and bleating car horns, laughter drifting off fire escapes, basketballs kissing pavement, a window yawning wide and a mother calling down to her son on his bicycle.

Which is to say, it sounds a bit like a Blood Orange song – balmy, layered with voices, thick with the poetry of urban life. Or it’s a bit like how a Blood Orange song used to sound. These days the music feels more pastoral somehow. More open and orchestral. Gloomier too, and occasionally ecstatic. “Age appropriate,” says Devonté Hynes, who turns 40 in December. And perhaps not so much like New York City, his muse and lover of nearly 20 years.

Since 2011, Hynes has been crafting his wistful, timeless pop songs as Blood Orange, songs that feel cosmopolitan and fluid and, often, like a long embrace. Music to listen to from a supine position on your bedroom floor, remembering a place you’ve never been to. Music that he has made largely from his own bedroom since he was at secondary school, because he prefers that to the traditional studio set-up. He has made film scores (Palo Alto, Passing); TV soundtracks (We Are Who We Are, In Treatment); dance-punk songs (as part of Test Icicles); country-rock songs (as the solo artist Lightspeed Champion); songs for other people (Sky Ferreira, Solange, FKA twigs, Mariah Carey); classical symphonies (accompanied by orchestras in London, Toronto and Sydney); and dreamlike, heartbreaking songs that combine field recordings, the many instruments he can play (guitar, cello, bass, drums, piano, synths), the voices of his own friends and that undeniably sweet, Prince-like voice. Because he’s always widening his frame, it is difficult to identify any fixed musical signature, but you know a Blood Orange song when you hear it, even if it was gifted to somebody else.

“Dev’s one of those artists who everyone tries to imitate, consciously or unconsciously,” says his friend Lorde, who met him when she moved to New York City in the summer of 2021. She features on his new album, Essex Honey; he contributed to her latest project, Virgin. “It’s beautiful to me, but none get close to what he does.” Lorde first discovered Hynes at 14 years old, when she heard Solange’s Losing You playing from a stereo in somebody’s backyard in Auckland and followed the paper trail to his solo work. “It was distinct for its quality but felt like it had always been there,” she says. “Dev’s music is unmistakably him – subtle, sexy, infectious, rhythmic, many-voiced. It sounded like what I hoped adulthood was like, if you moved to a city and met the right people. And it’s ageing the best out of any modern pop, I think. It all sounds so good and effortless.”

Hynes strolls into the crowded Brazilian café in Greenwich Village where we’ve arranged to meet just after 3pm dressed in dark shorts, trainers and a Tottenham Hotspur jersey that recalls his lapsed-jock status. His thin, over-ear headphones, which he seems to go nowhere without, are blasting a master playlist he’s compiled of songs by Beach House (he wishes he’d found the title Depression Cherry first) and he has a book of interviews with the Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke tucked under his arm. “I think people are surprised when I say he’s one of my favourite directors,” says Hynes, who studied film and literature during sixth form.

Admittedly I count myself among the surprised. Hynes is a lean, mild-mannered Brit. He has the sort of open face that would invite strangers to ask for directions. He speaks softly; he sings in a high falsetto. His friends describe him in a language that verges on reverence: “If I hadn’t met him, I’d have had to make him up,” says the novelist Zadie Smith, who refers to him as a brother. The pair met in 2016, when Smith was teaching creative writing at NYU and President Trump had just been elected. “Dev to me was a light who made New York feel like somewhere good things could still happen.”

I’m positive, for my part, that it’s ridiculous to make judgements about someone’s worldview by an analysis of their disposition, but here I am, pointlessly trying to reconcile this gentle, elegant person with his love for Haneke, a man who leaves music out of all his movies and whose work feels intended to make his audience squirm. It seems incongruous with Hynes’s impressionistic, empathic songwriting, his affinity for the bohemian character of 1980s New York and those sumptuous tableaux from his often self-directed music videos.

But film is an integral element of his language; there is the sense that he’s a kind of frustrated filmmaker. “He’ll run from a camera, out of shyness,” says Ian Isiah, a longtime friend and frequent collaborator. “But he’s a genius behind one – directing, composing, writing.” Songs like Sutphin Boulevard, about a young boy who dresses in drag, scan like scenes from movies Hynes has directed in his mind. And Haneke’s Funny Games is on the syllabus of artworks to understand him. (Also on the syllabus: Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, Arthur Russell’s Calling Out of Context, William Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, and a YouTube video of Spurs highlights in the semifinal against Ajax in the 2019 Uefa Champions League.) Maybe his music can feel hopeful because its author is, by his own admission, “pessimistic and nihilistic”, and so it’s a means of self-soothing at the end of the world. “Haneke always assumes, which I also assume, that the audience is intelligent and that they’re going to understand the text,” Hynes says. We agree that Haneke, unlike most American filmmakers, recognises that violence is not at all spectacular, and that it’s rare to feel some existential crescendo towards any traumatic event that upends your life: tragedy happens because life does, and maybe there’s no reason at all for it. “It’s filmmaking that’s asking questions, but there’s no easy answer to them,” Hynes says. “It’s more of an exploration of a particular question, and I think I work in a similar way.”

“I’ve literally never written a song that wasn’t about myself. The only reason I make music is excavation, you know? To work through things” – Dev Hynes

In his music, Hynes favours diagnosis over prescription. His songs search and meander but rarely land anywhere concrete. His stories are troubled by whatever troubles him, whether they’re love songs or songs written from the perspective of women, as many of those on Coastal Grooves, his debut studio album as Blood Orange, are. “I’ve literally never written a song that wasn’t about myself,” he says. “The only reason I make music is excavation, you know? To work through things. I’m always thinking about the past.” You could say that Cupid Deluxe, the follow-up to Coastal Grooves, was a study of emotional transitions; that Freetown Sound was an interrogation of selfhood by way of the communal; that Negro Swan was a meditation on belonging, rejection and the meaning of family. “I think, when people get angry at films and art, it’s because they’re not being let off easy,” he says when I describe an experience I had with Haneke’s The Piano Teacher. “There’s no easy answer. It’s frustrating, because it’s like, what’s happening? Why am I watching this? Why am I feeling this way?”

Essex Honey offers no sweet or easy answers. It is, instead, sublimely melancholic. The cello abounds, plaintively and inquisitively. Voices echo, delay and reverberate. Percussion is unstable, prone to shifting mid-song and introducing jazzy drum improvisations or pulsing breakbeats. Grief-stricken images emerge like lily pads in a stream: broken, flickering lights; tight muscles; “knitted” hearts; swirling drains and dusky room corners; the floor, maybe the whole Earth, vanishing from beneath you. Hynes’s mother died suddenly in 2023, and many of these songs are an inventory of his attempts to reorientate himself in the world in the aftermath. “No, I can’t pretend I know everything ends / I just want to see again,” he sings on Somewhere in Between, over syncopated guitar licks and a faraway harmonica. Hynes is no stranger to exploring his own pain in his art, or to connecting that pain, tenderly illuminated, to broader political struggles. But where his writing could at times be heavy with metaphor and character-building, here he is in his clearest, most unadorned register. Essex Honey, his first album in seven years, seems to be asking: how do you move forward, how can you start the day or wash your hands or create music, when it feels like everything has gone to shit? He doesn’t bother to answer the question. Or, there is no answer. There is only the bed to make, the dishes to clean, the laundry to be done, the pigeons crowding around the spikes on the windowsill. There is only the next morning.

Here is how he would tell it, how he has always told it: Hynes never “moved” to New York. There was no decision or reason to come to New York, which, in the grand scheme of things, seems reason enough. Why does anybody move anywhere anyway? To see if they’ll be different maybe. To see if there’s a cure for loneliness.

Hynes was born and raised in Ilford, a town in a part of east London that’s considered to be Essex and known mostly for its association with a manufacturer of black and white photographic materials. His dad, who was born in Sierra Leone, was the manager of a department store, and his Guyanese mother was a healthcare consultant who counselled teen mothers. He is the youngest of three siblings and spent most of his childhood alone in his bedroom, which he decorated with various posters: Smashing Pumpkins, Slipknot, David Beckham. In his dark sanctuary, he could practise the cello, or tape songs off the radio, and escape the bullying he incurred from the neighbourhood boy racers: the name-calling, being spat on during bus rides, getting jumped and occasionally hospitalised. (One time, he told Sam Fragoso on the podcast Talk Easy, he was beaten so badly that his mother enrolled him in karate lessons.) He had an ear for classical music and a bottomless appreciation for Bach but was seduced by the fast-paced Ministry of Sound CDs that his older sister, Louise, a “big rave listener”, liked to collect, and when he was older she sometimes took him to the parties. “Essex has this very rich musical history that no one knows about, because people in Essex don’t really care,” Hynes says. Many of the EDM soundscapes he heard at Ministry – Underworld, the Prodigy, Stereolab – form the spine of Essex Honey, with the splashes of drum’n’bass that feel genuinely new in the Blood Orange discography. It’s perhaps his first album that feels distinctly like London.

Hynes’s career-launching band, like his eventual relocation to America, was a byproduct of accident and circumstance. He was 18 or 19 and addicted to playing in short-lived punk bands. One such group, then called Balls, was slated to support the Unicorns for a show in Nottingham, but one of the bandmates, the visual artist Ferry Gouw, had to return to Indonesia to renew his visa. Gouw told the club promoter that Balls couldn’t play the show but that his friends’ band, Test Icicles, could replace them. But the band did not exist. So the other former members of Balls, Sam Mehran and Rory Attwell, wrote some songs with Hynes, who played the guitar, keyboard and sang, and they played the show under that new name.

The jagged, freaked-out music that Test Icicles made together, central to the new rave movement of the mid-2000s, is a far cry from the slick, jazz-funk-tinged R&B of today’s Blood Orange. They had no bassist and used a drum machine in lieu of an actual drummer – and got booed at a lot of their early shows because of it. “The UK trio is hard, fast and viciously catchy, but above all scary,” reads a Pitchfork review of For Screening Purposes Only, the sole album Test Icicles recorded. “Guitars don’t chug and wail; they whinny and scream.” A one-star show review in The Guardian from 2005 balks at a previous live set from the band, during which 1) Attwell broke his nose stage-diving, 2) Mehran was launched down a staircase by a security guard, and 3) Hynes “severed his big toe on a broken bottle and passed out at his keyboard”. In short, it was weird, it was metal, it was one influence for Charli xcx’s Brat, that imperious 2024 declaration of club dominance that turned everything green for a summer.

The band broke up in 2006. They were meant to do an American tour and had all secured their visas to travel, but they cancelled their shows. Suddenly the world Hynes had read about in Please Kill Me, a punk history of New York City, seemed like a plausible destination. He was already couch-surfing with a backpack in London, and because he knew someone who knew someone with their own couch in Long Island City, that was where he went. In America, his music changed. He recorded some folksy, orchestral country-pop songs in Omaha, Nebraska – home of the famed record label Saddle Creek – under the name Lightspeed Champion. That project, written with and produced by Bright Eyes’ Mike Mogis, abandoned the abrasive, dance-punk sound of Test Icicles and replaced it with lush strings and spare atmospherics. It sounded, according to Hynes, then 22, like “losing your virginity for the fifth time”. Two albums and three years later, Hynes had reinvented himself again. He had tweaked his sound to make “songs that could be sung by a drag queen”. He had a new name. And the first line he sang as Blood Orange, over the spunky, muted guitar riffs of Forget It, announced his evolution: “I feel unique / Not yet complete.”

Because he makes music compulsively, and because it’s the primary outlet he uses to work through his emotions, Hynes has always conceived of his albums as time capsules of his inner life. He likes how Adele titles her records after the ages when the living that produced the album happened: 19, 21, 25, 30. You could do the same to make sense of some of his work, as a sort of mental exercise – Essex Honey becomes 37 or 38 or 39, Negro Swan is retitled 32 or 33, Freetown Sound comprises 30 or 31, and so on. He made Cupid Deluxe, for example, when he was 26 and 27, just as New York was beginning to feel like home to him, which was also, unfortunately, the year his East Village apartment burned down and everything he owned went up in flames: clothes, hard drives, sentimental items, music, his puppy, Cupid. Accordingly, the album fixates on states of in-betweenness: situationships, subway rides, decisions yet unmade.

“Explaining this can sound a little … I don’t know,” Hynes says sheepishly. “But it’s very easy for me to make music. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to be music I think is good, or music that I like or think speaks to where I am, but the actual ability to create it is, I find, extremely easy.”

Still, it’s been six years since the last full-length Blood Orange project: 2019’s Angel’s Pulse – the only mixtape in his catalogue, distinctly looser and less precious than his usual recordings, like a master painter revealing their sketches or a filmmaker exhibiting first drafts of a screenplay. It’s not as if there’s been no music since then. It’s just that much of it, aside from the Four Songs EP he released in 2022, has been made for others: operatic works for Marni, classical ones composed or performed for orchestras, scores for the directors Paul Schrader and Melina Matsoukas. This constant stream of wordless classical music has allowed his mind to wander back through his memories and to contend with the turmoil of the world outside.

“It’s very easy for me to make music. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to be music I think is good, or music that I like or think speaks to where I am, but the actual ability to create it is, I find, extremely easy” – Dev Hynes

A lot of life has happened in that six-year interim, a lot of grief to be accounted for. A global pandemic. Genocides in Sudan and Tigray and Gaza. Assaults on trans people in America and the UK. Rampant xenophobia and the hyperactivity of immigration enforcement officers across the US. “I think the thing that was stopping me from going all the way in was that I was really struggling to find the why – like, why should this album even exist?” Hynes says. There were things happening in his life, and he was always writing, but he couldn’t marshal his energy towards making a coherent project because life itself was not coherent. He felt moored, indelibly, to the past. The dam broke one morning in 2023, when he was pacing around his Greenwich Village apartment, allowing Spotify to select music he might like, and a song came on that felt telegraphed from inside his own head. It was Sufjan Stevens’s Fourth of July, from his 2015 album Carrie & Lowell, a collection of sparse, downtempo folk songs that narrate the death of the musician’s mother from stomach cancer.

“I had just lost my mother, and Sufjan’s mother had passed away, and the description was eerily similar to how I was feeling,” Hynes says. “It sounds so simple, but in that moment I was like, oh, I need to get over myself.” It suddenly felt ridiculous, even offensive, that he had the ability to make music people wanted to hear and that, in his mourning, he was withholding it. He told the poet, singer-songwriter and filmmaker Mustafa about discovering the song while they were hanging out together in Paris, how he couldn’t stop hearing it everywhere, and they bonded over their shared love for it. “It opened this conversation for us about music and the way it impacts us, how it could sometimes free us from our isolation,” says Mustafa, who writes often about grief, memory and dispossession; his baritone voice emerges throughout Essex Honey. “It reminded him of why music is made at all.”

“I started thinking back to when I was younger, just making music for fun and playing in bands in London or whatever,” Hynes says. The thought freed him up. “And so that moment really did change how I thought. Even with live shows. I’ve always had this weird relationship to them and wouldn’t do too many, but I started thinking about how insane it was that I could do it and it started feeling like I needed to honour it.”

And so the music changed again. Some of the songs on Essex Honey, to be fair, are old; Life, with Tirzah and Charlotte Dos Santos, was made 12 years ago, and most of the arrangement hasn’t been touched except for some tweaks on the bass guitar. But where previous Blood Orange albums have been largely city-centric, this one can sound almost rural, like he took a sabbatical in the UK countryside and emerged anew, with new questions. His voice, which he used to hate, is still surrounded by others, but there are more songs here with just Hynes than anything since Coastal Grooves. “I think I’d lived so long in America that, subconsciously, I knew I wanted to bring it back to England,” he says. “So I just started spending more time there, in England and other parts of Europe, and, naturally, the music started happening.” Many of the songs became shaded by the music that he grew up on, and so we get samples of the Durutti Column and interpolations of Elliott Smith, or classical compositions that explode midway through and veer sharply from the concert hall to the club.

“I’ve loved observing the evolution of his music,” says the musician Liam Benzvi, a frequent collaborator who sings background on Essex Honey. “He really tries to create these vast sonic landscapes now and keeps making things get bigger and bigger.” Benzvi remembers first hearing Coastal Grooves when he was at college in Minneapolis, nursing an obsession with Prince and the Replacements. “No one was really using drum machines the way he was, in this non-electroclashy way,” he says. “These weren’t hard, abrasive sounds. They were delicate drum machine sounds. And probably the last person to do that was Kanye, on 808s & Heartbreak. But I loved how soft it was, and how pretty [Hynes’s] voice was, and how you never knew where his guitar was going to go.”

Hynes himself recognises how the music has evolved. “I think that, now, I want to be so clear,” he says. Death, after all, is the least abstract condition, and its appearance in his life has made him cleave to solidity and directness. “Some of my biggest lyrical references, like Morrissey, have a way with these really blunt sentences – ‘I was looking for a job, and then I found a job,’” he says. His new album is replete with that cadence. “I don’t want to be here any more,” he sings plainly on Thinking Clean, which collides a wild, jazzy drum break with a four-on–the-floor house beat. “I wash my hands and stare into the drain,” on The Last of England. Some sentences repeat, gradually accumulating severity, coalescing into theses. “Hard to look at you,” he sings on Look at You, a line that returns two tracks later. “I just want to see again,” he sings over and over on Somewhere in Between. Certain cello passages, provided by the Danish cellist Cæcille Trier and reworked, apparently beyond her recognition, by Hynes, recur like overtures or flashbacks. “I wanted it to feel like someone remembering songs, or moments, or situations,” he says. “Maybe that little situation is a little wart in your head, but it’s different in reality. Maybe now it feels sweeter than it was before. Or maybe it’s worse than that. But I wanted it to feel like a memory package.”

In Grand Union, a 2019 collection of short stories by Zadie Smith, there’s a scene inspired by a “religious experience” she had at a Blood Orange concert in New York. The protagonist, a 77-year-old woman called Wendy English, has been reflecting on her life, and her disappeared sister, and she arrives at a show in Central Park that makes her feel as if her ears, everyone’s ears, are connected to their souls. “Historically speaking,” she thinks, “men with guitars have held their instruments in a certain way and pointed them at you like a penis and stood in the centre of whatever space and drawn all energy to them like a lightning rod stuck on a church spire. He didn’t do any of that. For most of the show we had no idea where he was, really: he kept hiding behind other people, other instruments. He had his locks tied in a bun and wore some very high-waisted, salmon-coloured trousers. Meanwhile, the crowd was filled with every type of true self imaginable in the tristate area.”

In some ways, this observation about that “hiding” articulates the centrifugal instinct at the heart of Hynes’s music as Blood Orange. “Dev never does anything alone,” Isiah says. “He understands that community is really important. At any point, in any country, in any hotel room, this man has a laptop up in a makeshift studio, jamming alone, and then adding you to a group text like, ‘Hey, meet me here, I need you to come now.’” Hynes is never precious about being the primary focus of anything at all. “He’s been so good at parting from authorship, in a time when so much of being an artist is about building borders around that authorship,” Mustafa says. Hynes’s albums, his live shows, are a tapestry of voices. The voices belong to other people – Caroline Polachek, Eva Tolkin, Ian Isiah, Adam Bainbridge, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Carly Rae Jepsen, Mustafa, Janet Mock, the list goes on – but they’re also, somehow, his own. Perhaps this deference is a vestige of self-belief, the knowledge that your voice is clear enough to be heard even when you’ve said nothing at all, even when you’ve got someone else to say it for you. On those perfect, early pop songs he wrote for other artists – Sky Ferreira’s Everything Is Embarrassing, for example, or the songs from Solange’s True EP – you can almost hear his demo, that silken, feminine voice, cutting through the mix. “I’ve never really felt a connection to performing my own music,” says Hynes, who famously has disliked touring. “But I love performing other people’s music. Doing classical recitals or playing in other people’s bands. I think it’s because, in my head, Blood Orange exists as a recording project for myself.” (He promises he’s excited to tour the album this autumn: he has finally arrived at a place where he knows how to enjoy playing his own music live.)

It is rare for an auteur to be so yielding. He tends to inspire acts of creation in others; because of him, Isiah has started producing songs, scoring, making treatments and jingles, and calling in his friends to make music. In 2022, Benzvi joined Hynes on stage when Blood Orange was opening for a 15-night Harry Styles residency at Madison Square Garden in Manhattan. Hynes encouraged him to play songs from his debut album, Acts of Service, which had come out earlier that year. “He would let me do that, like, five times, in front of this crowd of screaming girls that were there every single night because they’d bought tickets for the entire residency,” Benzvi says. “And they would just know what was coming, when it was coming. So they would be chanting his name, then chanting my name – it was so weird and surreal.” The pair now support each other on their respective records. Hynes is also featured on the single Other Guys, from Benzvi’s 2024 sophomore album, … And His Splash Band, and appeared in the song’s video.

In some ways, the approach Hynes takes to collaboration resembles the hodgepodge formation of Test Icicles: whoever is around is at risk of being pulled into his orbit. “It’s kind of always been like that,” he admits. “If you’re around me when I’m in one of those phases, and they are like phases, where I’m really working on it, you’re gonna be involved, whether you’re a musician or not. Because if you’re there, you’re a friend of mine, and I trust you. And I actually prefer it if you can’t play music – those are the opinions I genuinely listen to.” He works like a maestro, conducting a symphony he wrote all the parts for.

“I’ve never really felt a connection to performing my own music. But I love performing other people’s music” – Dev Hynes

Smith, for example, has a guest slot singing a few lines on a song from Essex Honey. She’d gone over to his new place and it was set up like a studio, and she improvised over something purely because he needed a voice to fill a gap. She didn’t expect to be on the record. She’d earned money as a cabaret singer when she was a student at King’s College, Cambridge, but for the most part, she sings at home. “He makes a space in which you feel free and don’t need to be ashamed. For me, singing was always very attached to shame – I have a lot of excellent musicians in my family, a few of them world-class musicians, and I always judged myself against that standard and thought I could never be enough,” she tells me. “But Dev helped me realise that I have a really adolescent way of thinking about singing. I imagined you had to sing like Stevie Wonder or just not do it at all. I don’t get the impression Dev is ever after perfection. He’s always looking for something human and real.”

Lorde feels similarly. “With Dev, everything is up for grabs and anyone’s idea could be the best,” she tells me. “I love watching Dev work – picking up instruments on a whim, no judgement, just letting it come out of him, sometimes surprising himself. I love how he uses vocalists like paint colours, the combination of voices he’s returned to over and over, and new ones who sing just a line or two. But I think it’s Dev singing the whole time, using other bodies to get the colours he wants.” He taught her what true collaboration looks like, that sharing the floor is always to your advantage. “If you’re around long enough and he loves you, you’ll be on the record. It has the effect of feeling like real life encapsulated in music, which is difficult to do,” she says. “He’s always a step ahead, adding something totally surprising but unmistakably him, there in his studio with the projector playing a film, bent over an instrument, smiling, humming to himself.”

Hair: Soichi Inagaki at MA+Talent using BUMBLE AND BUMBLE. Make-up: Crystabel Efemena Riley at Julian Watson Agency using MÁDARA. Set design: Tilly Power at The Magnet Agency. Photographic assistants: Ed Bourmier and Daiki Nakajima. Styling assistants: Bella Kavanagh and Myles Mansfield. Tailor: Felix Gumbsch. Set-design assistant: Sean Kirwin. Production: REPRO. Executive producer: Rachael Evans. Senior producer: Zuzana Kostolanska. Production assistants: Meron Ayele and Valentyn Korolkov

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine, on sale internationally on 25 September 2025. Pre-order here.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.