Rewrite

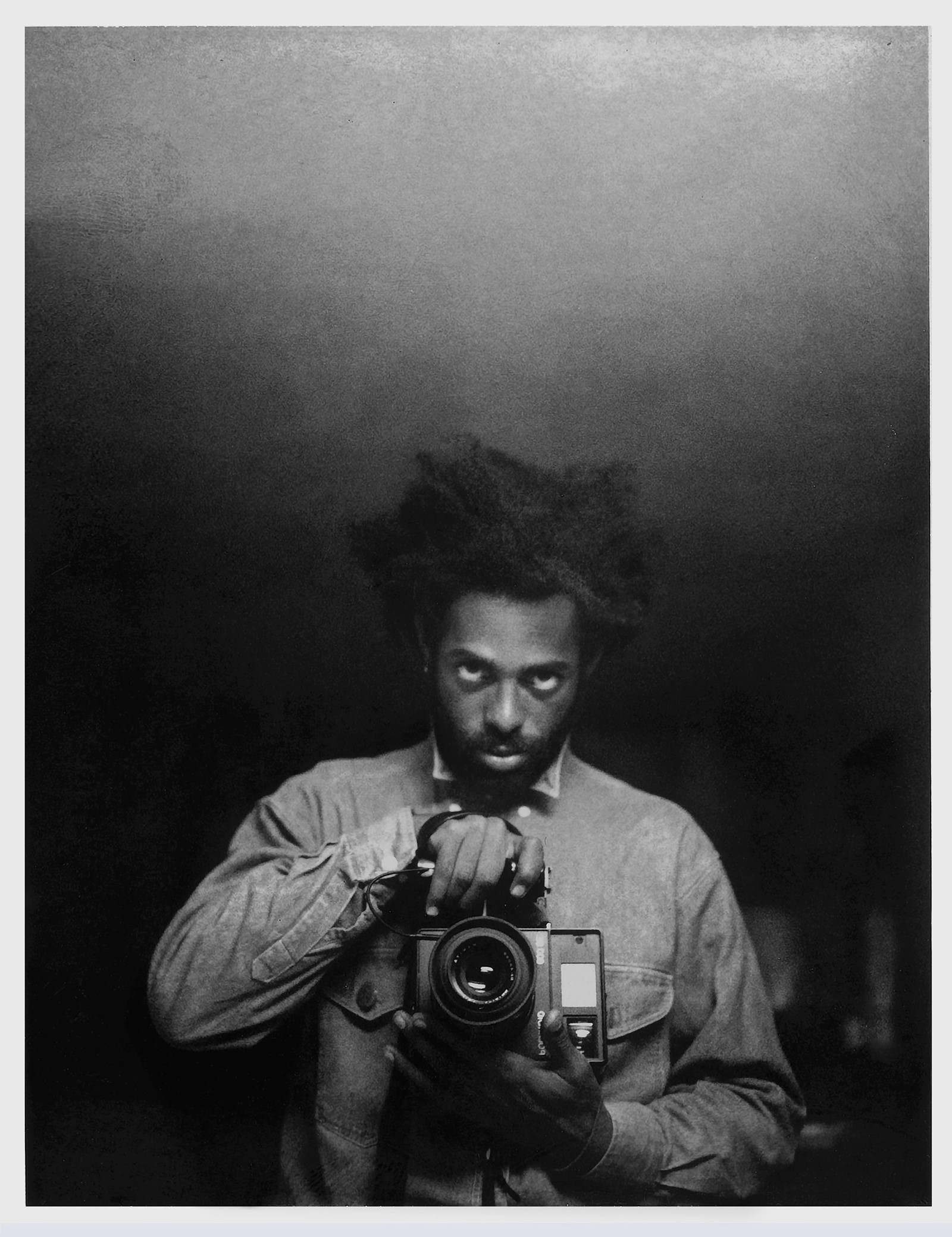

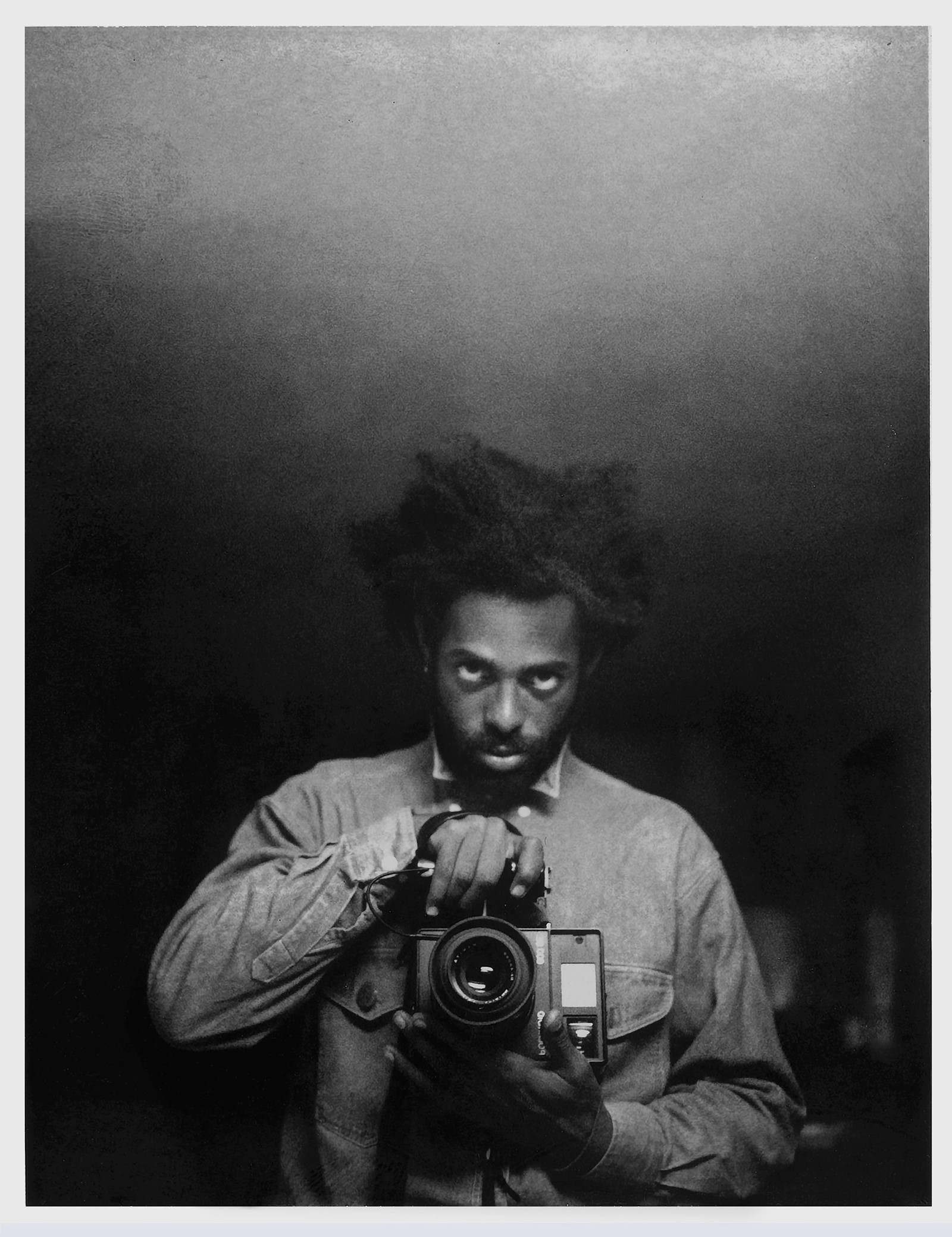

Lead ImageTheo Parrish, 4 April 2025Courtesy of Pinault Collection. Photography by Raphael Massart

Music bleeds into almost every aspect of Arthur Jafa’s extraordinary work. An American visual artist and filmmaker devoted to capturing the richness of the Black experience, music is a key element of Jafa’s video works, two of which form the heart of a new group exhibition, Corps et âmes, at the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection in Paris. Translating into English as ‘Body and Soul’, the exhibition explores the representation of the body in art in contemporary art and features some 40 artists alongside Jafa, including Ana Mendieta, Deana Lawson, Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas and Kerry James Marshall.

In the museum’s vast rotunda space sits Jafa’s most famous work, Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016), a seven-minute video that collages iconic images of Black American culture, anonymous video clips scoured from the internet – many of violence and police brutality – and images of the red-hot sun. The result is a gut-wrenching meditation on Black identity, history, culture, and suffering, set to Kanye West and Chance the Rapper’s gospel-inspired, incandescent song Ultralight Beam. Then there’s Aghdra (2021), Jafa’s apocalyptic, elusive 85-minute film featuring chopped and screwed soul music by Roberta Flack, the Isley Brothers, Rose Royce and more, set to a computer-generated image of a sun setting on a pixelated black sea (Jafa has said that the POV of the film is from the hold on a slave ship).

Jafa’s work is a rich jumping off point for Cyrus Goberville, the head of cultural programs at the Bourse de Commerce, a man whose job includes curating a program of live music events at the museum in response to their artists and exhibitions (François Pinault owns one of the largest contemporary art collections in the world, with approximately 10,000 works). Since its opening in 2021, the Bourse de Commerce has hosted an impressive lineup of musicians, welcoming Arca, Dev Hynes, Dean Blunt and Theo Parrish. But audiences expecting run-of-the-mill performances by their favourite musicians will be disappointed; the Bourse de Commerce’s musical program is instead a space for avant-garde experimentation and innovation, with eclectic performances catered specifically for the museum’s vast, Tadao Ando-designed rotunda space. Here, music hovers somewhere in the space between art and sound, and like the art on the museum’s walls, it is challenging, designed to provoke.

When I visit the museum in late April, the musical event of the evening is by Low Jack, an electronic music composer and DJ based in Paris. Created partly in response to Jafa’s gospel film akingdoncomethas (2018), Low Jack’s performance Lacrimosa is a haunting meditation on death, bridging electronic and classical music with help from the voices of Kingdom Molongi Choir. May will see more events created in response to Jafa’s work, with upcoming performances by Crystallmess, who will invite audiences on a journey through the American South, Detroit techno pioneer Robert Hood, and a new generation of Parisian rap artists influenced by Caribbean cultures, curated by French artist Pol Taburet.

Below, Cyrus Goberville talks more about Arthur Jafa’s relationship with music, curating events for a museum space, and what he is listening to at the moment.

Violet Conroy: How did you end up working at the Bourse de Commerce?

Cyrus Goberville: I was running a small record label before; this is my first institutional job. In terms of cultural programming, there are a lot of great things happening in Paris: the Pompidou has a really good dance program, the Palais de Tokyo has an amazing performance program. But this kind of music, where the approach is across contemporary art, fashion and performance – hybrid music, made by artists – was not really shown in Paris. When I got the job, I told the Pinault collection about some crazy good spaces, like the ICA in London, Public Records in New York, or Cafe OTO in London. We didn’t have places like this in Paris, but we needed them. And we wanted them in the very centre of Paris. Most experimental places – like Ormside projects in London, for instance – are quite far from the centre.

VC: What attracted you to working for an institution – are you trying to bring underground music to the mainstream?

CG: I wouldn’t say the Bourse de Commerce is mainstream because contemporary art is still very niche. The place is famous, but it’s still niche, and the program here is also niche. Politically, it’s something that interests me: how do you bring the niche to a form of mainstream? When I was putting on club nights when I was younger, we weren’t making money, we were stressed, sad, and nobody was turning up. And then we did an event in an artist-run space, and suddenly it was packed. At that time, I understood that what I really wanted to do was to bring music to people who are not in music.

VC: Tell me more about the cultural program here at the Bourse de Commerce. How do you make musical events in response to the art?

CG: This is not a traditional music venue, so it’s best to do shows that couldn’t tour anywhere else. Here, it’s not about one kind of music. The music can be traditional, contemporary, or super old; it can be reggae, pop, rap, electronic, it can be anything. I want to mix every reference. We also always do co-programming. Most of the time, it’s record labels from across the world, festivals, friends of friends, people that I meet in the street. I know a lot about music but I’m not a specialist in anything. If I have to put on a jazz show, I know that I can do a good jazz show, but I cannot do the best, and it’s the same with every other genre of music.

VC: How have you curated the musical program in response to Arthur Jafa’s work?

CG: When I discovered Love is the Message, The Message is Death, I was struck by how Jafa mixes and gathers images together that shouldn’t be together. It’s always paradoxical, but after a few minutes, you start to understand what he’s trying to do. Like Jean-Luc Godard, he has the same way of putting images together, and I try to do the same with music. I’m trying to develop something very paradoxical.

“Peter Doig has the craziest reggae collection, Anne Imhof knows so much about hardcore rock music, Arthur Jafa is crazy about soul music” – Cyrus Goberville

VC: Music is an important element of Arthur Jafa’s work, especially in the two video works currently on show at the Bourse de Commerce: Love is the Message, The Message is Death and Aghdra. Could you talk more about Jafa’s relationship with music?

CG: The artists in this exhibition have a relationship with music because they’re in the studio listening to it all day. Peter Doig has the craziest reggae collection, Anne Imhof knows so much about hardcore rock music, Arthur Jafa is crazy about soul music … his vision of R&B, techno, and Black music is at a level that you cannot even imagine. It comes from the gods, it’s something that is unique. The video that you mention, Aghdra uses old funk, disco, R&B, soul songs mostly, that are very pitched down in the chopped and screwed technique, a technique that DJ Screw from Houston invented. We don’t want to listen to Ye anymore, but that track [Ultralight Beam] that Jafa uses in Love is the Message, The Message is Death is something that is pretty unique, and it shouldn’t be censored.

VC: What’s been your favourite event here so far?

CG: We had Theo Parrish a few weeks ago. When I was going to Plastic People [a club in London] when I was younger, he was kind of my hero, and I saw him playing so many times. Having him here was very emotional for me. And then Arca. I love seeing an artist not being stressed, being sure about what she’s doing, when it’s totally improvised. There’s a form of divinity or spirituality [when she plays], and I love this because you can find only find this in artists or religious people.

VC: What music are you listening to at the moment?

CG: I listened to Both Sides Now by Joni Mitchell today, it’s such a crazy record. I’m also digging into Tom Wilson’s discography. He was a producer who worked with Bob Dylan, The Velvet Underground and Sun Ra. He died of a stroke in 1978, so his life was extremely short, but I’m deeply into him at the moment.

Find out more about the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection’s upcoming events in Paris here.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageTheo Parrish, 4 April 2025Courtesy of Pinault Collection. Photography by Raphael Massart

Music bleeds into almost every aspect of Arthur Jafa’s extraordinary work. An American visual artist and filmmaker devoted to capturing the richness of the Black experience, music is a key element of Jafa’s video works, two of which form the heart of a new group exhibition, Corps et âmes, at the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection in Paris. Translating into English as ‘Body and Soul’, the exhibition explores the representation of the body in art in contemporary art and features some 40 artists alongside Jafa, including Ana Mendieta, Deana Lawson, Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas and Kerry James Marshall.

In the museum’s vast rotunda space sits Jafa’s most famous work, Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016), a seven-minute video that collages iconic images of Black American culture, anonymous video clips scoured from the internet – many of violence and police brutality – and images of the red-hot sun. The result is a gut-wrenching meditation on Black identity, history, culture, and suffering, set to Kanye West and Chance the Rapper’s gospel-inspired, incandescent song Ultralight Beam. Then there’s Aghdra (2021), Jafa’s apocalyptic, elusive 85-minute film featuring chopped and screwed soul music by Roberta Flack, the Isley Brothers, Rose Royce and more, set to a computer-generated image of a sun setting on a pixelated black sea (Jafa has said that the POV of the film is from the hold on a slave ship).

Jafa’s work is a rich jumping off point for Cyrus Goberville, the head of cultural programs at the Bourse de Commerce, a man whose job includes curating a program of live music events at the museum in response to their artists and exhibitions (François Pinault owns one of the largest contemporary art collections in the world, with approximately 10,000 works). Since its opening in 2021, the Bourse de Commerce has hosted an impressive lineup of musicians, welcoming Arca, Dev Hynes, Dean Blunt and Theo Parrish. But audiences expecting run-of-the-mill performances by their favourite musicians will be disappointed; the Bourse de Commerce’s musical program is instead a space for avant-garde experimentation and innovation, with eclectic performances catered specifically for the museum’s vast, Tadao Ando-designed rotunda space. Here, music hovers somewhere in the space between art and sound, and like the art on the museum’s walls, it is challenging, designed to provoke.

When I visit the museum in late April, the musical event of the evening is by Low Jack, an electronic music composer and DJ based in Paris. Created partly in response to Jafa’s gospel film akingdoncomethas (2018), Low Jack’s performance Lacrimosa is a haunting meditation on death, bridging electronic and classical music with help from the voices of Kingdom Molongi Choir. May will see more events created in response to Jafa’s work, with upcoming performances by Crystallmess, who will invite audiences on a journey through the American South, Detroit techno pioneer Robert Hood, and a new generation of Parisian rap artists influenced by Caribbean cultures, curated by French artist Pol Taburet.

Below, Cyrus Goberville talks more about Arthur Jafa’s relationship with music, curating events for a museum space, and what he is listening to at the moment.

Violet Conroy: How did you end up working at the Bourse de Commerce?

Cyrus Goberville: I was running a small record label before; this is my first institutional job. In terms of cultural programming, there are a lot of great things happening in Paris: the Pompidou has a really good dance program, the Palais de Tokyo has an amazing performance program. But this kind of music, where the approach is across contemporary art, fashion and performance – hybrid music, made by artists – was not really shown in Paris. When I got the job, I told the Pinault collection about some crazy good spaces, like the ICA in London, Public Records in New York, or Cafe OTO in London. We didn’t have places like this in Paris, but we needed them. And we wanted them in the very centre of Paris. Most experimental places – like Ormside projects in London, for instance – are quite far from the centre.

VC: What attracted you to working for an institution – are you trying to bring underground music to the mainstream?

CG: I wouldn’t say the Bourse de Commerce is mainstream because contemporary art is still very niche. The place is famous, but it’s still niche, and the program here is also niche. Politically, it’s something that interests me: how do you bring the niche to a form of mainstream? When I was putting on club nights when I was younger, we weren’t making money, we were stressed, sad, and nobody was turning up. And then we did an event in an artist-run space, and suddenly it was packed. At that time, I understood that what I really wanted to do was to bring music to people who are not in music.

VC: Tell me more about the cultural program here at the Bourse de Commerce. How do you make musical events in response to the art?

CG: This is not a traditional music venue, so it’s best to do shows that couldn’t tour anywhere else. Here, it’s not about one kind of music. The music can be traditional, contemporary, or super old; it can be reggae, pop, rap, electronic, it can be anything. I want to mix every reference. We also always do co-programming. Most of the time, it’s record labels from across the world, festivals, friends of friends, people that I meet in the street. I know a lot about music but I’m not a specialist in anything. If I have to put on a jazz show, I know that I can do a good jazz show, but I cannot do the best, and it’s the same with every other genre of music.

VC: How have you curated the musical program in response to Arthur Jafa’s work?

CG: When I discovered Love is the Message, The Message is Death, I was struck by how Jafa mixes and gathers images together that shouldn’t be together. It’s always paradoxical, but after a few minutes, you start to understand what he’s trying to do. Like Jean-Luc Godard, he has the same way of putting images together, and I try to do the same with music. I’m trying to develop something very paradoxical.

“Peter Doig has the craziest reggae collection, Anne Imhof knows so much about hardcore rock music, Arthur Jafa is crazy about soul music” – Cyrus Goberville

VC: Music is an important element of Arthur Jafa’s work, especially in the two video works currently on show at the Bourse de Commerce: Love is the Message, The Message is Death and Aghdra. Could you talk more about Jafa’s relationship with music?

CG: The artists in this exhibition have a relationship with music because they’re in the studio listening to it all day. Peter Doig has the craziest reggae collection, Anne Imhof knows so much about hardcore rock music, Arthur Jafa is crazy about soul music … his vision of R&B, techno, and Black music is at a level that you cannot even imagine. It comes from the gods, it’s something that is unique. The video that you mention, Aghdra uses old funk, disco, R&B, soul songs mostly, that are very pitched down in the chopped and screwed technique, a technique that DJ Screw from Houston invented. We don’t want to listen to Ye anymore, but that track [Ultralight Beam] that Jafa uses in Love is the Message, The Message is Death is something that is pretty unique, and it shouldn’t be censored.

VC: What’s been your favourite event here so far?

CG: We had Theo Parrish a few weeks ago. When I was going to Plastic People [a club in London] when I was younger, he was kind of my hero, and I saw him playing so many times. Having him here was very emotional for me. And then Arca. I love seeing an artist not being stressed, being sure about what she’s doing, when it’s totally improvised. There’s a form of divinity or spirituality [when she plays], and I love this because you can find only find this in artists or religious people.

VC: What music are you listening to at the moment?

CG: I listened to Both Sides Now by Joni Mitchell today, it’s such a crazy record. I’m also digging into Tom Wilson’s discography. He was a producer who worked with Bob Dylan, The Velvet Underground and Sun Ra. He died of a stroke in 1978, so his life was extremely short, but I’m deeply into him at the moment.

Find out more about the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection’s upcoming events in Paris here.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.