Rewrite

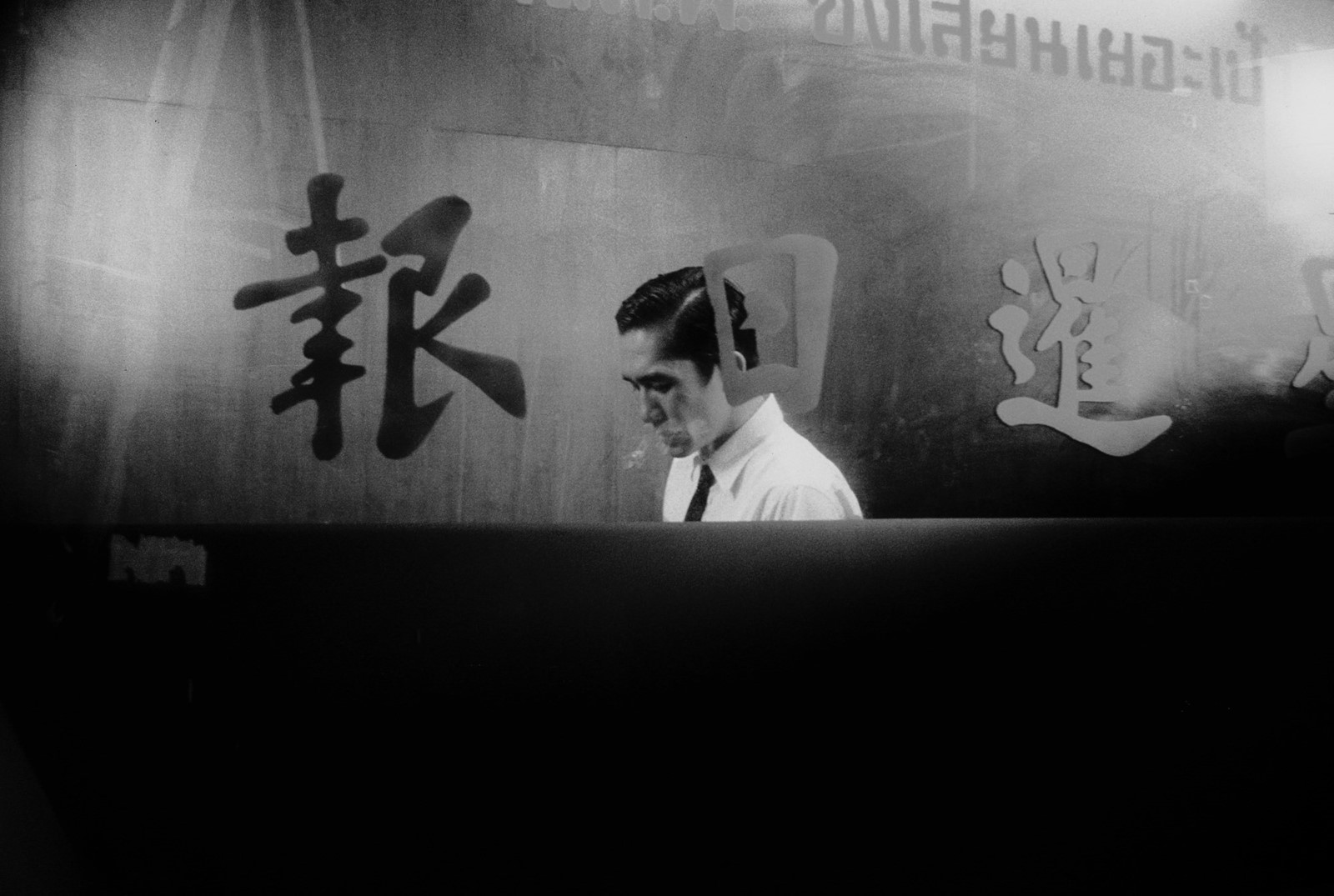

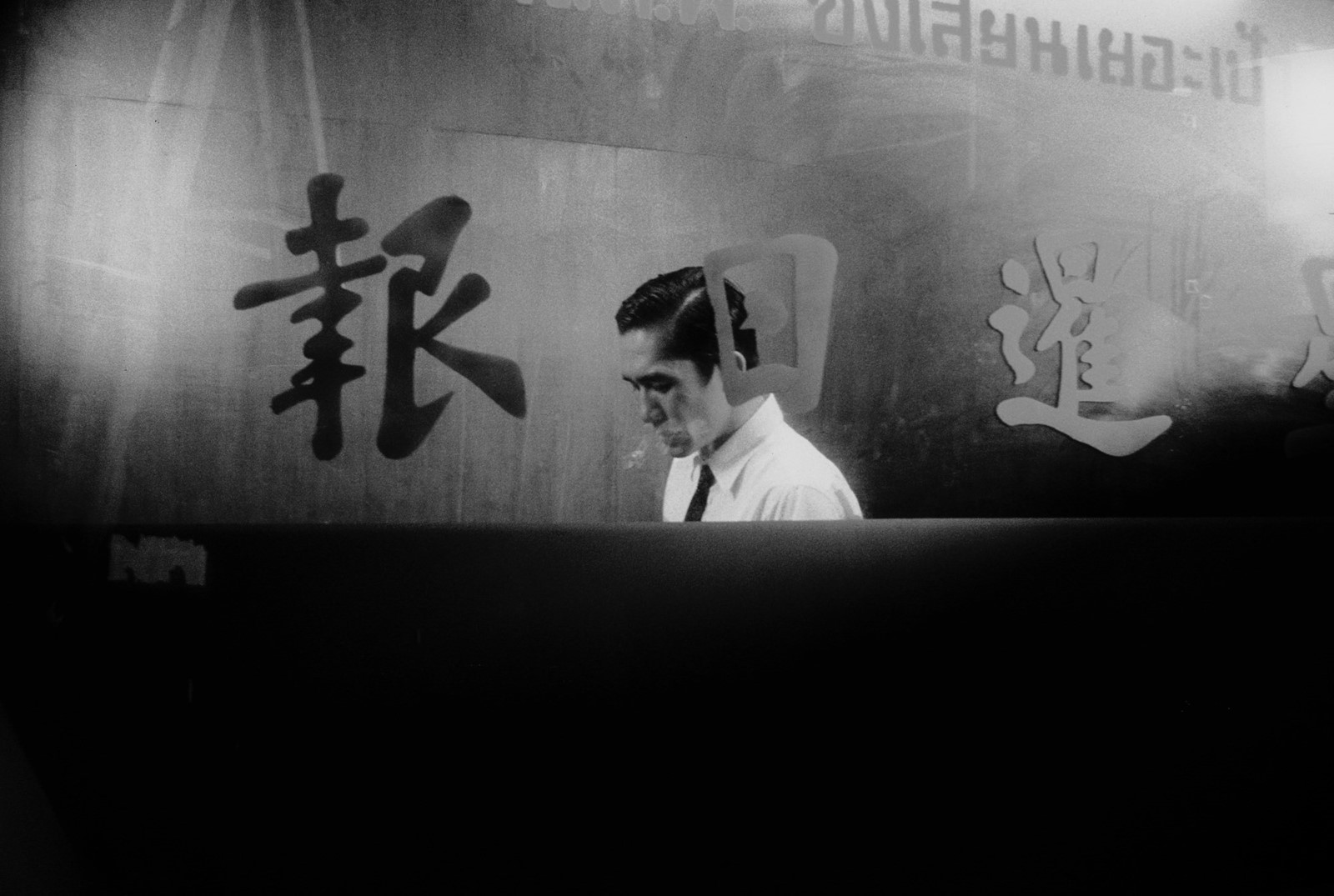

Lead ImageSolace by Wing ShyaCourtesy of Session Press and Dashwood Books

What’s most striking about the work of Hong Kong photographer Wing Shya – best known for his behind-the-scenes snapshots from the films of Wong Kar-wai – is just how dreamy and sensual it all feels. Bursting with saturated colour, blurred motion, and a profound, romantic sense of longing, his shots from the sets of Cannes sensations Happy Together and In the Mood For Love, in particular, mark the artist as an introspective and emotionally astute storyteller. But Solace, the stunning new monograph of Wing’s work from Session Press, is also distinct from the New York publisher’s previous photo books on artists like Nobuyoshi Araki, Daido Moriyama and Ren Hang. How so? “I have to be honest,” Wing confesses over a video call. “I didn’t know how to do photos. Everything is from mistakes.”

After graduating from the Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Canada in the mid-90s, Wing returned to Hong Kong to work as an in-house graphic designer and art director for a studio run by actor and musician Eric Kwok that decade. Album covers and magazine posters were the meat and bones of the job, but when Wong Kar-wai’s production company came knocking one day, Wing suddenly found himself working as a backup stills photographer. “Jet Tone [Films] were trying to save money,” he tells me, recalling his role on a commercial for Japanese brand Takeo Kikuchi starring Tadanobu Asano. “But shooting in Hong Kong food markets is chaotic and crazy. The Japanese photographer couldn’t get into the shooting location because there were so many people, so they used my photo for the print advertisement.”

This was the springboard towards a long-running collaboration with the arthouse icon, whose next major project, the queer romantic drama Happy Together, would go on to win the Cannes Best Director prize in 1997. It was Wing’s first feature collaboration with the director: after being flown out to Buenos Aires as a backup once more, he got his break when one of the more experienced creatives was simply too exhausted to do his job. “The first stills photographer was gay,” Wing explains, “so Mr Wong actually asked him to write some of the story. He stayed in his room to write some [scenes] and then when we went to shoot he was really tired because he didn’t sleep. That’s basically how I ended up being the stills photographer.”

His evocative shots from Happy Together form a captivating central focus in Solace, but Wing claims he had little idea what he was doing at the time. “The blurry, out-of-focus photos? It’s because I was so into the dancing [of actors Tony Leung and Leslie Cheung] that I forgot to turn on the auto-focus,” he says. Another unconventional photo of the duo, who portray two queer men in an intense and tumultuous relationship in the film, was eventually used for the movie’s promotional campaign. “The final poster is [shot from] far away because my camera shutter was so noisy. I had no idea that [I was supposed to use] a special soundproof case. They were like, ‘Get out, Wing! Further! Further!’ And so I could only shoot them real small because I had to stand so far away.”

It wasn’t just the crew that he wound up with his rackety camera antics. One of the most vibrant images in ‘Solace’ was the source of much frustration for its subject. “We took it in the train station, and since it was super noisy the director decided that they weren’t going to record the sound,” Wing recalls of one off-guard shot of Cheung preparing for a pensive, emotion-processing scene. Wing got up close, “but because my machine is so noisy, he couldn’t get into the mood.” After repeatedly asking him to stop, the actor got so upset that he reported Wing to the director, which forced an explanation from the photographer: “I said, ‘Leslie, if you hate me, it’s okay. I don’t care about making people upset, I just want to do my job well.’”

The image itself, shot on green-tinged Fujifilm “because it was cheaper than Kodak”, is dazzling. “I found Argentina really grey,” Wing says. “In my school, we all liked cross-processing – where you buy positive film and process it in negative C41 processing, which makes the colour really strong … In Argentina, we’d just go to a one-hour processing lab on the street, and they only had C41 – so it becomes like a cross-processor. I didn’t really plan it, I had no choice!” The end result, and Wing’s enthusiasm for his role, ultimately endeared popstar-actor Cheung so much to him that they became close friends thereafter: “Leslie was like, ‘From now on, you are my photographer’,” says Wing. “I thought he was joking, but back in Hong Kong, he called me to shoot his concerts, and all the photos for the magazines. It all came from this photo.”

Being largely forced to shoot between takes rather than during filming otherwise imbued a unique quality in Wing’s photos. In capturing liminal moments of actors still getting into character, or performing outside of the boundaries of the script, he unconsciously expands upon the narratives captured in the final film. “It creates a kind of mystery,” he concurs. “So, even when I got the sound box, I continued shooting the before and after. I found those moments more interesting.”

Shots like that of Leung and Cheung laughing during a cigarette break on Happy Together contrast wonderfully with the intense relationship depicted between their characters in the film. “They were really good friends,” Wing remembers. “Even after the movie, they would play mahjong together. I think they even lived in the same building. They would go to each other’s house for dinner.” Leung, meanwhile, was every bit the romantic that Wong’s films would lead us to believe: Wing recalls the time he bought everyone on set a rose on Valentine’s Day, and handed them out as they walked back to their hotels. Such stories only deepen the charm of the character he would appear as in Wong’s next film, In the Mood for Love, a tale of unrequited love in a pokey, mid-century Hong Kong hotel which would win Leung the Cannes Best Actor prize in 2001.

Wing’s saturated photos from the magnificent sets of the latter are another highlight of Solace, particularly those captured inside a pink-hued hotel bedroom decorated with orchid wallpaper, wood furnishings and red cushioned headboards. His saturated colours intensify the passionate connotations, but the between-takes photos also magnify the film’s core themes of desire and longing. One shot sees Leung handsomely sat in a corner, taking a furtive glance into an ornate hand mirror; another captures Maggie Cheung reading a book on a bed in the same room via the reflection of a vanity. The two lovelorn characters are separated spatially, but at the same time inescapably connected through the means of a visual portal.

Wing’s shot of Maggie Cheung, seemingly collapsed from exhaustion while wearing her iconic blue-pink floral cheongsam on the bed in this room, is another highlight that adds even greater weight to the film’s story. “This was a break after we had been shooting for almost 20 hours,” Wing says. “Most people went to sleep, but Maggie and I went back to the room. I told her to do whatever she wanted: don’t follow the script. She was actually holding a knife like she wanted to kill somebody but I shot her legs instead. I find that if I don’t tell the whole story, it can make it more interesting.” It makes for an effective visual metaphor, a lonely and incomplete individual exhausted and anguished by the weight of personal emotional turmoil.

Wing would continue to collaborate with Wong Kar-wai on several projects thereafter, including The Hand and 2046, while later work would span brands like Louis Vuitton, Maison Margiela and, most recently, Chanel (Wing was out shooting on Hong Kong’s streets until 5am the day before our call, for a new branded short film directed by 2021 Venice Golden Lion winner Audrey Diwan). Pop culture icons as varied as Shu Qi, Pharrell Williams, and Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, meanwhile, have served as focal points in Wing’s recent commercial projects. It’s his personal shots of Hong Kong, though, that ultimately anchor the Solace monograph in a place of enchantment and nostalgia, perfectly mirroring the kinds of emotions conveyed in Wong’s beloved films.

“I still feel Hong Kong is so romantic,” Wing concludes, as I highlight shots of a great purple mist over a mountain ridge; a glimpse of the sunrise behind the iconic Two IFC skyscraper shot from Causeway Bay; and the juxtaposition of a curving cloud cluster and a bending highway overpass. But whether these warm hues, leaking lights and dreamlike blurs are truly unintentional mistakes, as Wing claims, or the product of a photographer with an uncanny ability to capture a fleeting emotion in time, feels irrelevant. Happy accidents are rarely as timeless and intoxicating as these.

Solace by Wing Shya is published by Session Press, and is out now via Dashwood Books. There will be a book signing event in Tokyo at Ginza Tsutaya on September 6 and at Dashwood Books on November 20, followed by an exhibition at Dashwood Project on November 21.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageSolace by Wing ShyaCourtesy of Session Press and Dashwood Books

What’s most striking about the work of Hong Kong photographer Wing Shya – best known for his behind-the-scenes snapshots from the films of Wong Kar-wai – is just how dreamy and sensual it all feels. Bursting with saturated colour, blurred motion, and a profound, romantic sense of longing, his shots from the sets of Cannes sensations Happy Together and In the Mood For Love, in particular, mark the artist as an introspective and emotionally astute storyteller. But Solace, the stunning new monograph of Wing’s work from Session Press, is also distinct from the New York publisher’s previous photo books on artists like Nobuyoshi Araki, Daido Moriyama and Ren Hang. How so? “I have to be honest,” Wing confesses over a video call. “I didn’t know how to do photos. Everything is from mistakes.”

After graduating from the Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Canada in the mid-90s, Wing returned to Hong Kong to work as an in-house graphic designer and art director for a studio run by actor and musician Eric Kwok that decade. Album covers and magazine posters were the meat and bones of the job, but when Wong Kar-wai’s production company came knocking one day, Wing suddenly found himself working as a backup stills photographer. “Jet Tone [Films] were trying to save money,” he tells me, recalling his role on a commercial for Japanese brand Takeo Kikuchi starring Tadanobu Asano. “But shooting in Hong Kong food markets is chaotic and crazy. The Japanese photographer couldn’t get into the shooting location because there were so many people, so they used my photo for the print advertisement.”

This was the springboard towards a long-running collaboration with the arthouse icon, whose next major project, the queer romantic drama Happy Together, would go on to win the Cannes Best Director prize in 1997. It was Wing’s first feature collaboration with the director: after being flown out to Buenos Aires as a backup once more, he got his break when one of the more experienced creatives was simply too exhausted to do his job. “The first stills photographer was gay,” Wing explains, “so Mr Wong actually asked him to write some of the story. He stayed in his room to write some [scenes] and then when we went to shoot he was really tired because he didn’t sleep. That’s basically how I ended up being the stills photographer.”

His evocative shots from Happy Together form a captivating central focus in Solace, but Wing claims he had little idea what he was doing at the time. “The blurry, out-of-focus photos? It’s because I was so into the dancing [of actors Tony Leung and Leslie Cheung] that I forgot to turn on the auto-focus,” he says. Another unconventional photo of the duo, who portray two queer men in an intense and tumultuous relationship in the film, was eventually used for the movie’s promotional campaign. “The final poster is [shot from] far away because my camera shutter was so noisy. I had no idea that [I was supposed to use] a special soundproof case. They were like, ‘Get out, Wing! Further! Further!’ And so I could only shoot them real small because I had to stand so far away.”

It wasn’t just the crew that he wound up with his rackety camera antics. One of the most vibrant images in ‘Solace’ was the source of much frustration for its subject. “We took it in the train station, and since it was super noisy the director decided that they weren’t going to record the sound,” Wing recalls of one off-guard shot of Cheung preparing for a pensive, emotion-processing scene. Wing got up close, “but because my machine is so noisy, he couldn’t get into the mood.” After repeatedly asking him to stop, the actor got so upset that he reported Wing to the director, which forced an explanation from the photographer: “I said, ‘Leslie, if you hate me, it’s okay. I don’t care about making people upset, I just want to do my job well.’”

The image itself, shot on green-tinged Fujifilm “because it was cheaper than Kodak”, is dazzling. “I found Argentina really grey,” Wing says. “In my school, we all liked cross-processing – where you buy positive film and process it in negative C41 processing, which makes the colour really strong … In Argentina, we’d just go to a one-hour processing lab on the street, and they only had C41 – so it becomes like a cross-processor. I didn’t really plan it, I had no choice!” The end result, and Wing’s enthusiasm for his role, ultimately endeared popstar-actor Cheung so much to him that they became close friends thereafter: “Leslie was like, ‘From now on, you are my photographer’,” says Wing. “I thought he was joking, but back in Hong Kong, he called me to shoot his concerts, and all the photos for the magazines. It all came from this photo.”

Being largely forced to shoot between takes rather than during filming otherwise imbued a unique quality in Wing’s photos. In capturing liminal moments of actors still getting into character, or performing outside of the boundaries of the script, he unconsciously expands upon the narratives captured in the final film. “It creates a kind of mystery,” he concurs. “So, even when I got the sound box, I continued shooting the before and after. I found those moments more interesting.”

Shots like that of Leung and Cheung laughing during a cigarette break on Happy Together contrast wonderfully with the intense relationship depicted between their characters in the film. “They were really good friends,” Wing remembers. “Even after the movie, they would play mahjong together. I think they even lived in the same building. They would go to each other’s house for dinner.” Leung, meanwhile, was every bit the romantic that Wong’s films would lead us to believe: Wing recalls the time he bought everyone on set a rose on Valentine’s Day, and handed them out as they walked back to their hotels. Such stories only deepen the charm of the character he would appear as in Wong’s next film, In the Mood for Love, a tale of unrequited love in a pokey, mid-century Hong Kong hotel which would win Leung the Cannes Best Actor prize in 2001.

Wing’s saturated photos from the magnificent sets of the latter are another highlight of Solace, particularly those captured inside a pink-hued hotel bedroom decorated with orchid wallpaper, wood furnishings and red cushioned headboards. His saturated colours intensify the passionate connotations, but the between-takes photos also magnify the film’s core themes of desire and longing. One shot sees Leung handsomely sat in a corner, taking a furtive glance into an ornate hand mirror; another captures Maggie Cheung reading a book on a bed in the same room via the reflection of a vanity. The two lovelorn characters are separated spatially, but at the same time inescapably connected through the means of a visual portal.

Wing’s shot of Maggie Cheung, seemingly collapsed from exhaustion while wearing her iconic blue-pink floral cheongsam on the bed in this room, is another highlight that adds even greater weight to the film’s story. “This was a break after we had been shooting for almost 20 hours,” Wing says. “Most people went to sleep, but Maggie and I went back to the room. I told her to do whatever she wanted: don’t follow the script. She was actually holding a knife like she wanted to kill somebody but I shot her legs instead. I find that if I don’t tell the whole story, it can make it more interesting.” It makes for an effective visual metaphor, a lonely and incomplete individual exhausted and anguished by the weight of personal emotional turmoil.

Wing would continue to collaborate with Wong Kar-wai on several projects thereafter, including The Hand and 2046, while later work would span brands like Louis Vuitton, Maison Margiela and, most recently, Chanel (Wing was out shooting on Hong Kong’s streets until 5am the day before our call, for a new branded short film directed by 2021 Venice Golden Lion winner Audrey Diwan). Pop culture icons as varied as Shu Qi, Pharrell Williams, and Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, meanwhile, have served as focal points in Wing’s recent commercial projects. It’s his personal shots of Hong Kong, though, that ultimately anchor the Solace monograph in a place of enchantment and nostalgia, perfectly mirroring the kinds of emotions conveyed in Wong’s beloved films.

“I still feel Hong Kong is so romantic,” Wing concludes, as I highlight shots of a great purple mist over a mountain ridge; a glimpse of the sunrise behind the iconic Two IFC skyscraper shot from Causeway Bay; and the juxtaposition of a curving cloud cluster and a bending highway overpass. But whether these warm hues, leaking lights and dreamlike blurs are truly unintentional mistakes, as Wing claims, or the product of a photographer with an uncanny ability to capture a fleeting emotion in time, feels irrelevant. Happy accidents are rarely as timeless and intoxicating as these.

Solace by Wing Shya is published by Session Press, and is out now via Dashwood Books. There will be a book signing event in Tokyo at Ginza Tsutaya on September 6 and at Dashwood Books on November 20, followed by an exhibition at Dashwood Project on November 21.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.