Rewrite

The New York-based artist’s new book Distribution is the product of years spent studying the similarities between forests and cities

It’s true that first we shaped cities, then they shaped us. Growing up on the East Coast in Chicago and Baltimore before relocating to New York, Daniel Shea has always sought to understand these teeming epicentres of life – how their delicate puzzles of architecture, transport systems, and climates can dictate not only how people collectively behave, but who they individually become. Shea got his start nearly 20 years ago, after a documentary project about activists in West Virginia’s coal industry was spotted by a photo editor. Falling into the world of fashion, his practice is now split between anthropologically-inflected personal projects and ethereal imagery for brands like Proenza Schouler and magazines such as Dazed, Atmos and Double. Shea’s shrewd eye for spatiality and structure is evident even in his fashion work, whether capturing models manoeuvring through streets or the architectural lines of a Craig Green jacket.

His new monograph Distribution began with one deceptively simple question – how do you photograph a forest? It started in 2020 with meandering visits to a nature reserve near Queens, spiralling into a five-year study of woodlands in America, Japan and Mexico, which were used to inform new images in places like Dubai and Tokyo. The resulting book, however, is no straightforward documentary project. Shooting only through the windshields of moving cars and stripping all markers of place, Distribution immerses the viewer in a dizzying, gridded repetition of branches, highways, and skyscrapers that suffocatingly echo the notion of not being able to see the wood through the trees. Most unusually, it opens with a series of portraits of ‘Jessica’, a woman who represents the statistical median of a person living in the United States. Probing environments of density and the patterns they produce, it’s a striking, inquisitive piece of work that will leave you spinning – like emerging from a train station in rush hour.

Here, in his own words, Daniel Shea tells the story of its making:

“I don’t know why, but I’ve always loved cities. I’ve always lived in them and I’ve always sought to understand them. New York City has shaped me and continues to shape me. A very special thing about New York is the density – not only of people, but architecture. I moved here from Chicago, a city that is kind of a complete vision, where the buildings complement each other. In New York, the organising principle is: if you can build it, build whatever you want, wherever you can. It produces a type of organised chaos that ends up just being conducive for culture, and that type of chaos is endlessly engaging. I’m always looking for that in other parts of the world.

“The last book project I worked on was called 43-35 10th Street, and it had a pretty discrete idea about the way the world is organised, as told through the story of architecture over the last 50 to 100 years. It was about how a changing vision of capital inflected a type of value system in the architecture itself. After working on something so focused, I didn’t want to do something driven by a type of thesis. I wanted it to be much more about something simple, like perception or experience.

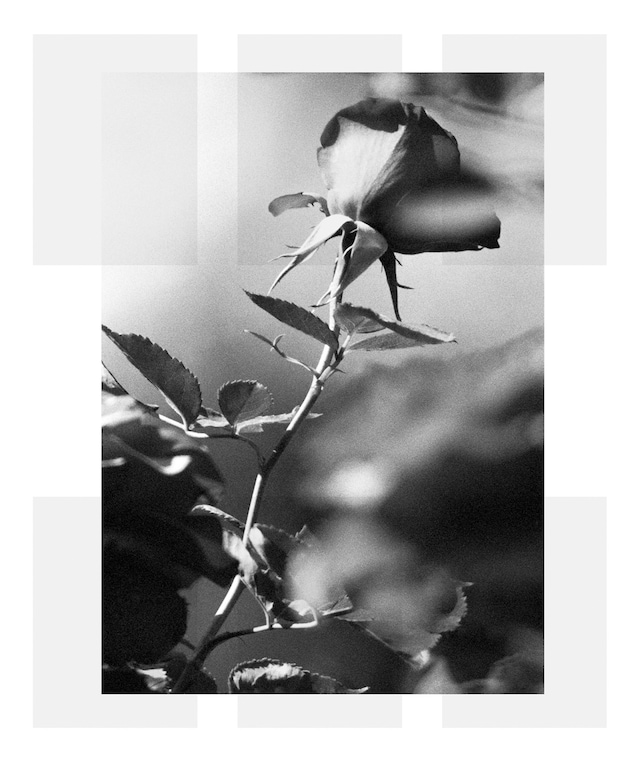

“I started this book by trying to figure out how to photograph forests, since I had spent so much time photographing cities. It was as Covid hit, so it was a natural way I could keep working. I’d just go to the woods, go for walks with a camera and try to figure out how to make an interesting picture. It took me a long time to figure it out. I started off photographing a forest preserve in Queens. My brother lives in North Carolina, so I went there, and then I photographed in forests in Mexico, California, Japan. But I never name these places [in the book], as they aren’t important. It’s more important that in the aggregate it becomes a generic wood. It’s a generic city. I removed language on signs and any regional specificity.

“After a few years figuring out the language of forests and trees, I started applying that to new pictures of architecture in cities. I would learn a little bit about what was interesting about those pictures and then go back to the forest, and then back to the city again. The first city I spent a lot of time working in was Dubai. I’m always looking for places that can resemble any type of place. A city like Dubai feels almost like a mirage. People describe it as soulless or lacking character in its newness, but there’s something much more specifically interesting about it as a representation of an ideal.

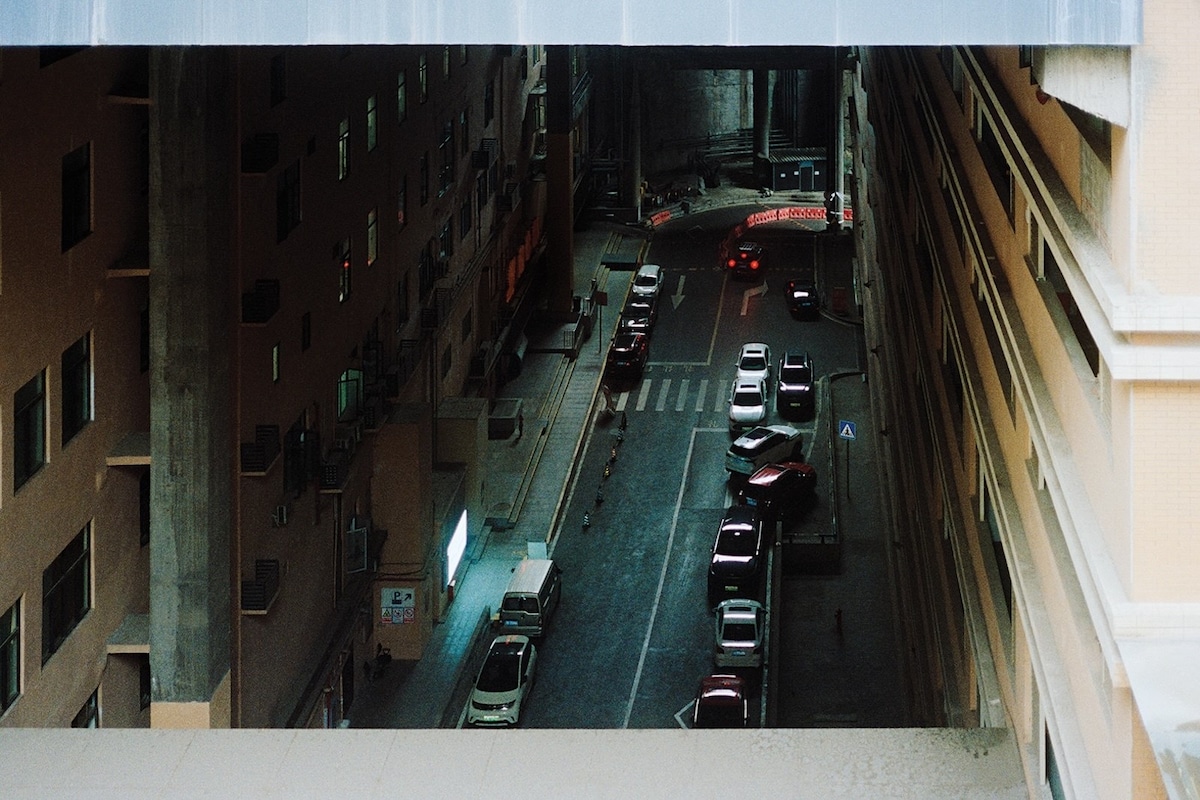

“It’s very hard to shoot on the street in Dubai without being stopped, so I found somebody who could drive me around and I just started photographing while we were driving. That developed a language of photography that’s used throughout the book, where even in Tokyo or New York, the pictures are almost always photographed through the windscreen of a moving car. The meat of the book is these images, which are gridded in the middle of the book. It’s meant to be kind of a slog to get through – an endless repetition of black-and-white rectangles that your eyes may go a little cross-eyed looking at.

“I liked the idea of opening the book with a sequence of pictures that immediately throws you off course. I hired an actor based on the statistical median of a person in America. She’s a 39-year-old woman living in San Bernardino, California, working a 9 to 5 in healthcare. It’s funny because the statistics describe the person, but what their life is like then becomes an interpretation, depending on your point of view. You might see it as a comfortable middle-class life with the type of stability built in – time to read books and watch television. There’s a picture of her watching Grey’s Anatomy, for example. Or you might see the worst dystopian vision of society, where we’re caught in a slog.

“In the beginning in the forest, I realised the totality of a wooded environment is what our experience of our surroundings often is – kind of like the wood through the trees analogy. There’s an image of a highway towards the beginning of the book that signifies the type of picture of a city that gets to a similar place. It’s hard to locate the subject – it’s a little bit out of focus. Years ago, when I started working on this project, the one thing I had written down was that the world is just a bunch of stuff distributed. It sounds so silly, but the way you interpret that distribution of objects, things and people informs your worldview. It’s actually very personal, how we understand the world, and that attempt to understand it through observing its patterns is what’s at the heart of this book.”

Distribution by Daniel Shea is published by Mack Books and is out now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

The New York-based artist’s new book Distribution is the product of years spent studying the similarities between forests and cities

It’s true that first we shaped cities, then they shaped us. Growing up on the East Coast in Chicago and Baltimore before relocating to New York, Daniel Shea has always sought to understand these teeming epicentres of life – how their delicate puzzles of architecture, transport systems, and climates can dictate not only how people collectively behave, but who they individually become. Shea got his start nearly 20 years ago, after a documentary project about activists in West Virginia’s coal industry was spotted by a photo editor. Falling into the world of fashion, his practice is now split between anthropologically-inflected personal projects and ethereal imagery for brands like Proenza Schouler and magazines such as Dazed, Atmos and Double. Shea’s shrewd eye for spatiality and structure is evident even in his fashion work, whether capturing models manoeuvring through streets or the architectural lines of a Craig Green jacket.

His new monograph Distribution began with one deceptively simple question – how do you photograph a forest? It started in 2020 with meandering visits to a nature reserve near Queens, spiralling into a five-year study of woodlands in America, Japan and Mexico, which were used to inform new images in places like Dubai and Tokyo. The resulting book, however, is no straightforward documentary project. Shooting only through the windshields of moving cars and stripping all markers of place, Distribution immerses the viewer in a dizzying, gridded repetition of branches, highways, and skyscrapers that suffocatingly echo the notion of not being able to see the wood through the trees. Most unusually, it opens with a series of portraits of ‘Jessica’, a woman who represents the statistical median of a person living in the United States. Probing environments of density and the patterns they produce, it’s a striking, inquisitive piece of work that will leave you spinning – like emerging from a train station in rush hour.

Here, in his own words, Daniel Shea tells the story of its making:

“I don’t know why, but I’ve always loved cities. I’ve always lived in them and I’ve always sought to understand them. New York City has shaped me and continues to shape me. A very special thing about New York is the density – not only of people, but architecture. I moved here from Chicago, a city that is kind of a complete vision, where the buildings complement each other. In New York, the organising principle is: if you can build it, build whatever you want, wherever you can. It produces a type of organised chaos that ends up just being conducive for culture, and that type of chaos is endlessly engaging. I’m always looking for that in other parts of the world.

“The last book project I worked on was called 43-35 10th Street, and it had a pretty discrete idea about the way the world is organised, as told through the story of architecture over the last 50 to 100 years. It was about how a changing vision of capital inflected a type of value system in the architecture itself. After working on something so focused, I didn’t want to do something driven by a type of thesis. I wanted it to be much more about something simple, like perception or experience.

“I started this book by trying to figure out how to photograph forests, since I had spent so much time photographing cities. It was as Covid hit, so it was a natural way I could keep working. I’d just go to the woods, go for walks with a camera and try to figure out how to make an interesting picture. It took me a long time to figure it out. I started off photographing a forest preserve in Queens. My brother lives in North Carolina, so I went there, and then I photographed in forests in Mexico, California, Japan. But I never name these places [in the book], as they aren’t important. It’s more important that in the aggregate it becomes a generic wood. It’s a generic city. I removed language on signs and any regional specificity.

“After a few years figuring out the language of forests and trees, I started applying that to new pictures of architecture in cities. I would learn a little bit about what was interesting about those pictures and then go back to the forest, and then back to the city again. The first city I spent a lot of time working in was Dubai. I’m always looking for places that can resemble any type of place. A city like Dubai feels almost like a mirage. People describe it as soulless or lacking character in its newness, but there’s something much more specifically interesting about it as a representation of an ideal.

“It’s very hard to shoot on the street in Dubai without being stopped, so I found somebody who could drive me around and I just started photographing while we were driving. That developed a language of photography that’s used throughout the book, where even in Tokyo or New York, the pictures are almost always photographed through the windscreen of a moving car. The meat of the book is these images, which are gridded in the middle of the book. It’s meant to be kind of a slog to get through – an endless repetition of black-and-white rectangles that your eyes may go a little cross-eyed looking at.

“I liked the idea of opening the book with a sequence of pictures that immediately throws you off course. I hired an actor based on the statistical median of a person in America. She’s a 39-year-old woman living in San Bernardino, California, working a 9 to 5 in healthcare. It’s funny because the statistics describe the person, but what their life is like then becomes an interpretation, depending on your point of view. You might see it as a comfortable middle-class life with the type of stability built in – time to read books and watch television. There’s a picture of her watching Grey’s Anatomy, for example. Or you might see the worst dystopian vision of society, where we’re caught in a slog.

“In the beginning in the forest, I realised the totality of a wooded environment is what our experience of our surroundings often is – kind of like the wood through the trees analogy. There’s an image of a highway towards the beginning of the book that signifies the type of picture of a city that gets to a similar place. It’s hard to locate the subject – it’s a little bit out of focus. Years ago, when I started working on this project, the one thing I had written down was that the world is just a bunch of stuff distributed. It sounds so silly, but the way you interpret that distribution of objects, things and people informs your worldview. It’s actually very personal, how we understand the world, and that attempt to understand it through observing its patterns is what’s at the heart of this book.”

Distribution by Daniel Shea is published by Mack Books and is out now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.