Rewrite

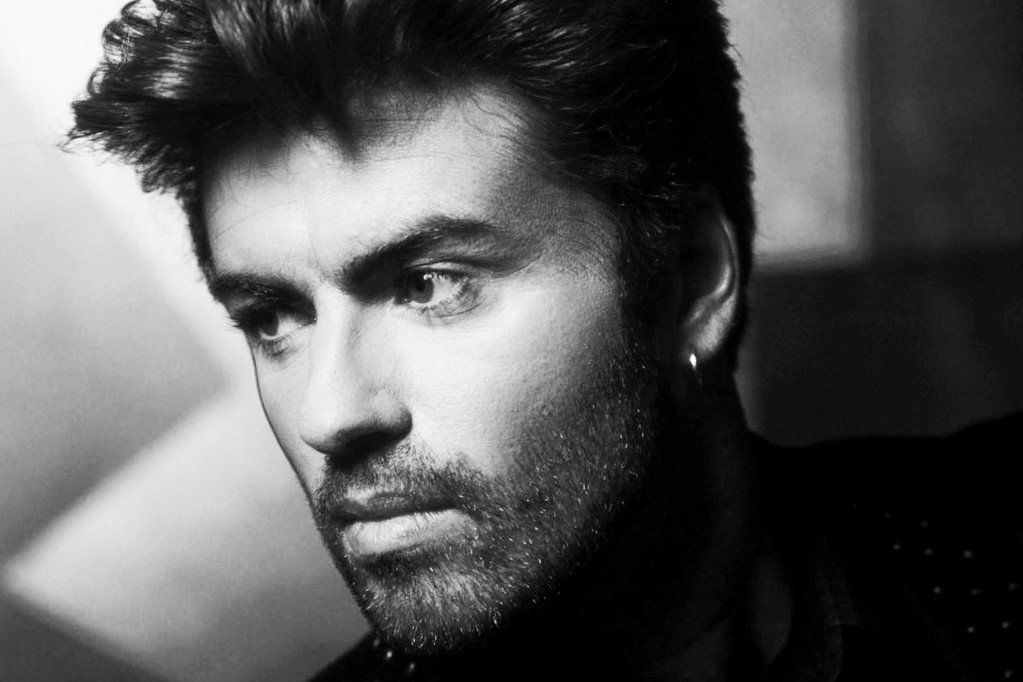

Lead ImageGeorge Michael, 1990© Brad Branson Estate

The late American photographer Brad Branson might not enjoy household name status like Herb Ritts, Mary Ellen Mark, and Brigitte Lacombe – who he sat alongside on the roster of renowned Los Angeles photographic agency Visage – but thanks to a renewed interest in the creative output of the 1980s and 90s, this may be about to change.

Somehow finding himself at the beating heart of cutting-edge creative culture both in his native Los Angeles and later in London, Branson depicted cultural figures, artists, musicians and fashion designers that defined the era. His graphic photographic style not only captured a movement but contributed to creating the aesthetic of that moment: artfully lit studio shots that tapped into an 80s revival of Old Hollywood glamour and techniques.

Musicians like Boy George, George Michael, Nina Hagen; artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Leigh Bowery; cultural provocateurs like John Waters and Bret Easton Ellis, models Naomi Campbell, Iman, Linda Evangelista and Carla Bruni, and designers like Stephen Jones, Vivienne Westwood, John Galliano and Thierry Mugler – to name but a few – all sat for portraits by Branson. And his work was published by the likes of Vanity Fair, Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine, The Face, Blitz, Attitude and Rolling Stone, as well as appearing on record sleeves and music posters.

“It was everybody’s dream to have a photograph taken by Brad because he made everybody look great,” said milliner Stephen Jones, speaking at his retrospective Stephen Jones, chapeaux d’artiste at the Palais Galliera in Paris. The show features Branson’s portrait of the young designer – part of Branson’s London milieu – in angel wings.

“It was everybody’s dream to have a photograph taken by Brad because he made everybody look great” –Stephen Jones

Stylist Kim Bowen, who was fashion editor at pioneering 80s magazine Blitz, recalls the shoot Branson did with Vivienne Westwood, resolutely future-facing and against airbrushing. “She wasn’t particularly optimistic about what was going to come out of the shoot with him because she didn’t like things that were old fashioned. And then once he’d done his magic, she just loved it,” Bowen says. “The real proof of the pudding was how much she used it. She used that picture for donkey’s years because it was so perfect. He didn’t retouch her into nothingness, he retouched her into somethingness.”

Having grown up in Los Angeles, one of Branson’s first jobs was as a projectionist to the great silent film actress Gloria Swanson. He was intrigued by the characters and glamour of Old Hollywood, and under the mentorship of photographer Paul Jasmin, learned about pioneers like George Hurrell – responsible for Greta Garbo’s glamour shots – and Horst P Horst, who is widely credited as being one of the pioneers of fashion photography.

When Branson got his own studio in the Crenshaw District Los Angeles, he turned it into the most happening nightclub in LA. Power Tools played host to the hottest DJs and was frequented by artists, musicians, and young and hip Los Angelinos. It’s no surprise some people claim it was an inspiration for Bret Easton Ellis’ debut novel Less Than Zero (perhaps because the book also depicts a hot club with a similar milieu). An article penned by Ellis for Vanity Fair in 1985, the year Less Than Zero was published, entitled In search of cool is an account of Branson, Ellis, and actor Judd Nelson slinking around LA hangouts, in a tone not dissimilar from the young and disaffected Less Than Zero narrator, Clay.

“Already drunk, tired of dancing, the whole idea of ‘cool’ fading from our minds, we headed toward Powertools, described by almost everyone we ran into during those weeks as the ‘hottest’, ‘the most happening’ club in all of Los Angeles,” wrote Ellis in the Vanity Fair article. “Powertools was started by Matt Dike, and our photographer, Bradford Branson, last November at Washington and Crenshaw, with an exhibition of model/artist Fritz Kok’s work. Andy Warhol, Annie Lennox, Andy Summers, Malcolm McClaren, Lauren Hutton, all showed up.”

The club was in fact so notable that Branson and Power Tools even get a mention in The Andy Warhol Diaries. “Saturday, March 30, 1985, Los Angeles: After dinner we went to Crenshaw Avenue way in the Black area of LA where Brad Branson who does photographs for Interview was giving his second weekly party. He’s doing it like a club, but with friends’ names on the list. And it was actually great, he had all the cute kids there and it was two floors and a garden part and some people said that Madonna had been there right before we got there.”

The Dutch artist Fritz Kok – also a model who was photographed by the likes of Bruce Weber – had begun collaborating with Branson under the name Indüstria after Brad saw his paintings inspired by the space age. Brad employed Old Hollywood-style retouching on-print and lighting techniques, and collages and backgrounds by Kok were often playful references to Art Deco, Constructivism and Cubism, and even communist propaganda posters.

After moving to London via Amsterdam, Branson once again found himself at the heart of culture via nightlife. Within the context of Thatcher’s Britain, the gay community found escapism in clubs like Kinky Gerlinky, where, as Kok says, you’d meet fellow “artists developing their creative personas”.“This escapism gave people a strong desire to become an icon or superhero of some sort,” Kok continues. “Indüstria actually catered to this desire, portraying people like an icon or superhero, complete with flawless skin, angel-wings or planetary orbits, around them,” he says.

They’d meet artists like Boy George and Leigh Bowery on the small West-end scene and end up creating images together. Bowery got the inspiration for a Snow White Evil Queen look after seeing three Evil Queen figurines Kok had bought at Disney Land and arranged in a “witch circle” in his flat. The subsequent shoot saw Branson photograph Bowery in a latex suit complete with ‘Evil Queen crown’.

A high point came when Indüstria was included in the groundbreaking 1988 Fashion and Surrealism show at the V&A. “We were blown away to see our work between Man Ray and Dalí,” recalls Kok. Though the collaborative pair went separate ways creatively, post-Indüstria, Branson continued photographing artists in London and the US, particularly for the music industry. His work included the record cover for George Michael’s Fast Love, Heal the Pain and Older, and he was the on-set photographer for the music videos for Freedom! ‘90 and Too Funky.

It seemed that everywhere Branson went, he found himself part of the creative in-crowd. One former Island Records exec told of how you wouldn’t know who you were going to bump into when dropping by Branson’s Leicester Square flat. Susan Pile, Warhol associate and then Senior VP of Marketing at Paramount Pictures, recalls one example of his influence on the LA scene: “We were having a premiere for Pretty in Pink at the Chinese Theatre, and the event was in such demand that I insisted that we pre-reserve seats for our guests who had RSVP’d. At the last minute, Brad, Fritz and George Michael wanted to come and we had to place them in the third row. They didn’t complain. The third row became the next sphere of VIP seats for future hot ticket screenings, which always cracked me up. The three of them would go around town making their mark like little rascals.”

Returning to Los Angeles in 1996, Branson changed course, developing film and writing projects and ultimately traveling and photographing the landscapes of the southwest US. He died on 13 December 2012 in a hospital in Hays, Kansas, due to complications of lung cancer. Kok now lives in Amsterdam and continues his creative work in photography and fashion.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageGeorge Michael, 1990© Brad Branson Estate

The late American photographer Brad Branson might not enjoy household name status like Herb Ritts, Mary Ellen Mark, and Brigitte Lacombe – who he sat alongside on the roster of renowned Los Angeles photographic agency Visage – but thanks to a renewed interest in the creative output of the 1980s and 90s, this may be about to change.

Somehow finding himself at the beating heart of cutting-edge creative culture both in his native Los Angeles and later in London, Branson depicted cultural figures, artists, musicians and fashion designers that defined the era. His graphic photographic style not only captured a movement but contributed to creating the aesthetic of that moment: artfully lit studio shots that tapped into an 80s revival of Old Hollywood glamour and techniques.

Musicians like Boy George, George Michael, Nina Hagen; artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Leigh Bowery; cultural provocateurs like John Waters and Bret Easton Ellis, models Naomi Campbell, Iman, Linda Evangelista and Carla Bruni, and designers like Stephen Jones, Vivienne Westwood, John Galliano and Thierry Mugler – to name but a few – all sat for portraits by Branson. And his work was published by the likes of Vanity Fair, Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine, The Face, Blitz, Attitude and Rolling Stone, as well as appearing on record sleeves and music posters.

“It was everybody’s dream to have a photograph taken by Brad because he made everybody look great,” said milliner Stephen Jones, speaking at his retrospective Stephen Jones, chapeaux d’artiste at the Palais Galliera in Paris. The show features Branson’s portrait of the young designer – part of Branson’s London milieu – in angel wings.

“It was everybody’s dream to have a photograph taken by Brad because he made everybody look great” –Stephen Jones

Stylist Kim Bowen, who was fashion editor at pioneering 80s magazine Blitz, recalls the shoot Branson did with Vivienne Westwood, resolutely future-facing and against airbrushing. “She wasn’t particularly optimistic about what was going to come out of the shoot with him because she didn’t like things that were old fashioned. And then once he’d done his magic, she just loved it,” Bowen says. “The real proof of the pudding was how much she used it. She used that picture for donkey’s years because it was so perfect. He didn’t retouch her into nothingness, he retouched her into somethingness.”

Having grown up in Los Angeles, one of Branson’s first jobs was as a projectionist to the great silent film actress Gloria Swanson. He was intrigued by the characters and glamour of Old Hollywood, and under the mentorship of photographer Paul Jasmin, learned about pioneers like George Hurrell – responsible for Greta Garbo’s glamour shots – and Horst P Horst, who is widely credited as being one of the pioneers of fashion photography.

When Branson got his own studio in the Crenshaw District Los Angeles, he turned it into the most happening nightclub in LA. Power Tools played host to the hottest DJs and was frequented by artists, musicians, and young and hip Los Angelinos. It’s no surprise some people claim it was an inspiration for Bret Easton Ellis’ debut novel Less Than Zero (perhaps because the book also depicts a hot club with a similar milieu). An article penned by Ellis for Vanity Fair in 1985, the year Less Than Zero was published, entitled In search of cool is an account of Branson, Ellis, and actor Judd Nelson slinking around LA hangouts, in a tone not dissimilar from the young and disaffected Less Than Zero narrator, Clay.

“Already drunk, tired of dancing, the whole idea of ‘cool’ fading from our minds, we headed toward Powertools, described by almost everyone we ran into during those weeks as the ‘hottest’, ‘the most happening’ club in all of Los Angeles,” wrote Ellis in the Vanity Fair article. “Powertools was started by Matt Dike, and our photographer, Bradford Branson, last November at Washington and Crenshaw, with an exhibition of model/artist Fritz Kok’s work. Andy Warhol, Annie Lennox, Andy Summers, Malcolm McClaren, Lauren Hutton, all showed up.”

The club was in fact so notable that Branson and Power Tools even get a mention in The Andy Warhol Diaries. “Saturday, March 30, 1985, Los Angeles: After dinner we went to Crenshaw Avenue way in the Black area of LA where Brad Branson who does photographs for Interview was giving his second weekly party. He’s doing it like a club, but with friends’ names on the list. And it was actually great, he had all the cute kids there and it was two floors and a garden part and some people said that Madonna had been there right before we got there.”

The Dutch artist Fritz Kok – also a model who was photographed by the likes of Bruce Weber – had begun collaborating with Branson under the name Indüstria after Brad saw his paintings inspired by the space age. Brad employed Old Hollywood-style retouching on-print and lighting techniques, and collages and backgrounds by Kok were often playful references to Art Deco, Constructivism and Cubism, and even communist propaganda posters.

After moving to London via Amsterdam, Branson once again found himself at the heart of culture via nightlife. Within the context of Thatcher’s Britain, the gay community found escapism in clubs like Kinky Gerlinky, where, as Kok says, you’d meet fellow “artists developing their creative personas”.“This escapism gave people a strong desire to become an icon or superhero of some sort,” Kok continues. “Indüstria actually catered to this desire, portraying people like an icon or superhero, complete with flawless skin, angel-wings or planetary orbits, around them,” he says.

They’d meet artists like Boy George and Leigh Bowery on the small West-end scene and end up creating images together. Bowery got the inspiration for a Snow White Evil Queen look after seeing three Evil Queen figurines Kok had bought at Disney Land and arranged in a “witch circle” in his flat. The subsequent shoot saw Branson photograph Bowery in a latex suit complete with ‘Evil Queen crown’.

A high point came when Indüstria was included in the groundbreaking 1988 Fashion and Surrealism show at the V&A. “We were blown away to see our work between Man Ray and Dalí,” recalls Kok. Though the collaborative pair went separate ways creatively, post-Indüstria, Branson continued photographing artists in London and the US, particularly for the music industry. His work included the record cover for George Michael’s Fast Love, Heal the Pain and Older, and he was the on-set photographer for the music videos for Freedom! ‘90 and Too Funky.

It seemed that everywhere Branson went, he found himself part of the creative in-crowd. One former Island Records exec told of how you wouldn’t know who you were going to bump into when dropping by Branson’s Leicester Square flat. Susan Pile, Warhol associate and then Senior VP of Marketing at Paramount Pictures, recalls one example of his influence on the LA scene: “We were having a premiere for Pretty in Pink at the Chinese Theatre, and the event was in such demand that I insisted that we pre-reserve seats for our guests who had RSVP’d. At the last minute, Brad, Fritz and George Michael wanted to come and we had to place them in the third row. They didn’t complain. The third row became the next sphere of VIP seats for future hot ticket screenings, which always cracked me up. The three of them would go around town making their mark like little rascals.”

Returning to Los Angeles in 1996, Branson changed course, developing film and writing projects and ultimately traveling and photographing the landscapes of the southwest US. He died on 13 December 2012 in a hospital in Hays, Kansas, due to complications of lung cancer. Kok now lives in Amsterdam and continues his creative work in photography and fashion.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.