Rewrite

Lead ImageGregory Crewdson, Untitled, From the series: Twilight , 1998-2002. Digital pigment print The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna, Permanent loan – Private Collection © Gregory Crewdson

America is an endlessly fascinating place shaped by the vastness and volatility of its extremes. It’s the only country that houses all five of Earth’s climates; a place where you can visit tropical beaches, dusty deserts and freezing cold mountains without ever technically leaving its borders. It’s at the vanguard of progressive visual arts and Western technological invention, home to the world’s highest concentration of billionaires and some of the most vibrant metropolitan cities. On the flip side of the coin, it’s also a place where appalling hate-driven violence runs rampant, punitive law systems have led to the world’s biggest prison population, and poverty deepens as the 1% grows richer. It’s a place of freedom and frustration, dreams and desperation, and – whether we like it or not – when it sneezes, the rest of the world braces itself for whatever cold, or indeed worse, might spread in suit.

Just a few weeks into Trump’s second landslide bid for presidency, times have never felt more heightened or surreal across the pond. As the year closes out, it feels like a pertinent moment to reflect on the best photo stories of American life published on AnOther this year. There are journeys into the hidden archives of government organisations, Polaroids taken in women’s prisons, and vital portraits of Black life during the 1960s. There are surreal visions of modern suburbia, lavish portrayals of East Coast wealth and heartwarming portrayals of teenagers coming of age. Looking back at the country’s complex history while asking what it means to be an American today, together, these photo series form a tapestry of experience, culture and feeling as varied as its 50 states.

Below, read more about ten American photo projects featured on AnOther in 2024.

Considered by many to be one of the most important photography books ever made, Larry Sultan and Mike Madel’s 1977 Evidence is the product of two years spent sifting through the archives of American government agencies and corporations. Gathering shadowy happenings inside laboratories, police stations, state departments, and offices of corporations, the pair sequenced these unearthed images without written context, forcing the viewer to cobble together meaning themselves. “It was clear to us at that time that these organisations were not giving us the wonderful future that they promised,” Mandel told AnOther upon the book’s republishing. “We knew these pictures of these strange translations of the landscape, or these clinical, objectifying images were a dystopian opportunity for us to create that message.”

Read our feature on the series here.

Drawing upon the menacing cinematic worlds of David Lynch and Alfred Hitchcock, Gregory Crewdson’s photographs of suburban America will make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up. The Massachusetts-born photographer has spent the past 25 years orchestrating wide-angled scenes of domestic darkness, where characters are frozen in thriller-like tableaus shot in humdrum houses and grey tree-lined streets. A new Prestel book brings together ten of his most acclaimed series, offering a comprehensive journey into his psychological photographic universe. “For me, everything begins and ends with Hitchcock’s movies,” he told AnOther. “I’m primarily interested in art – not only movies but paintings, photography, literature – that finds something extraordinary in everyday life.”

Read our feature on the series here.st-block-28

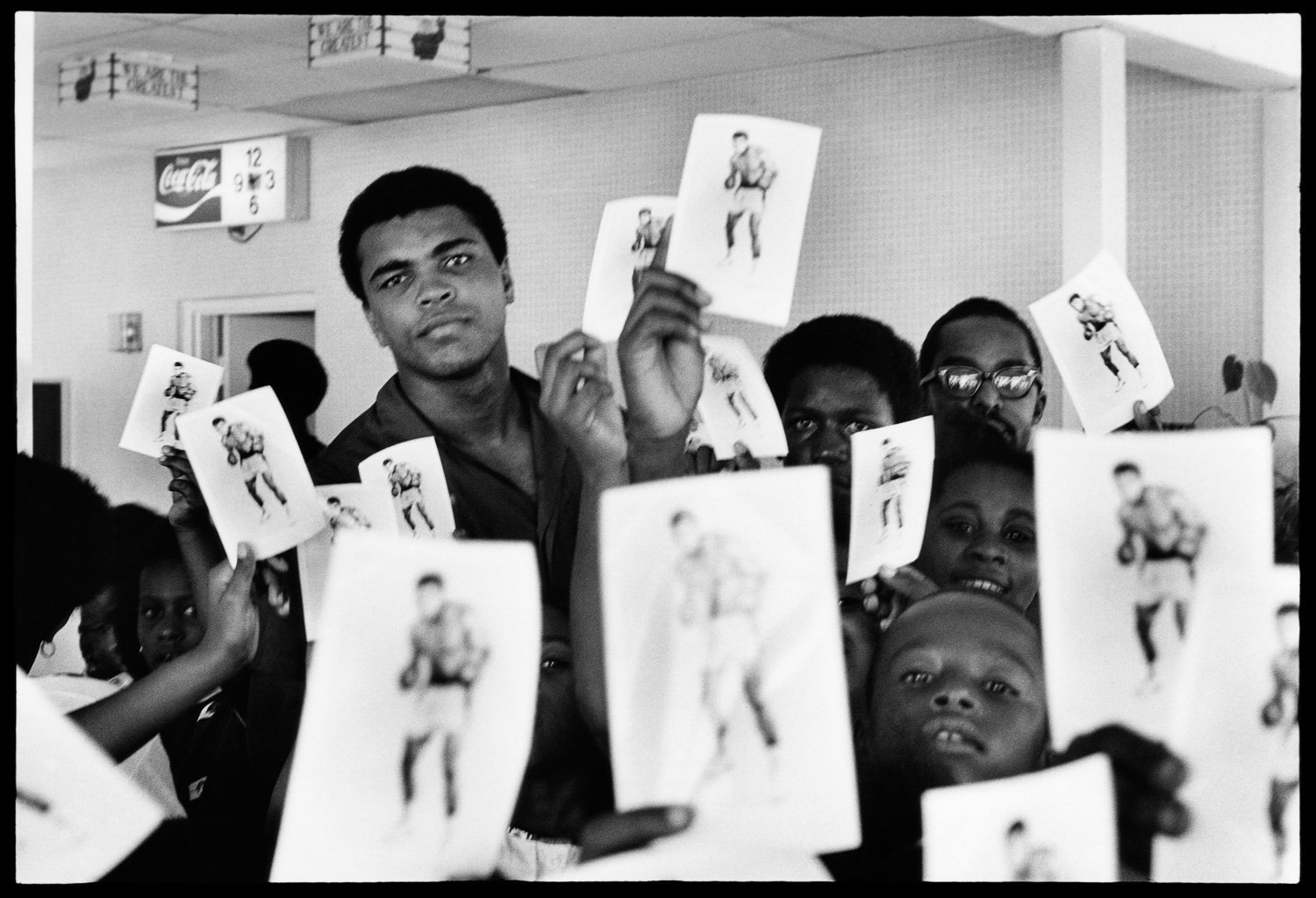

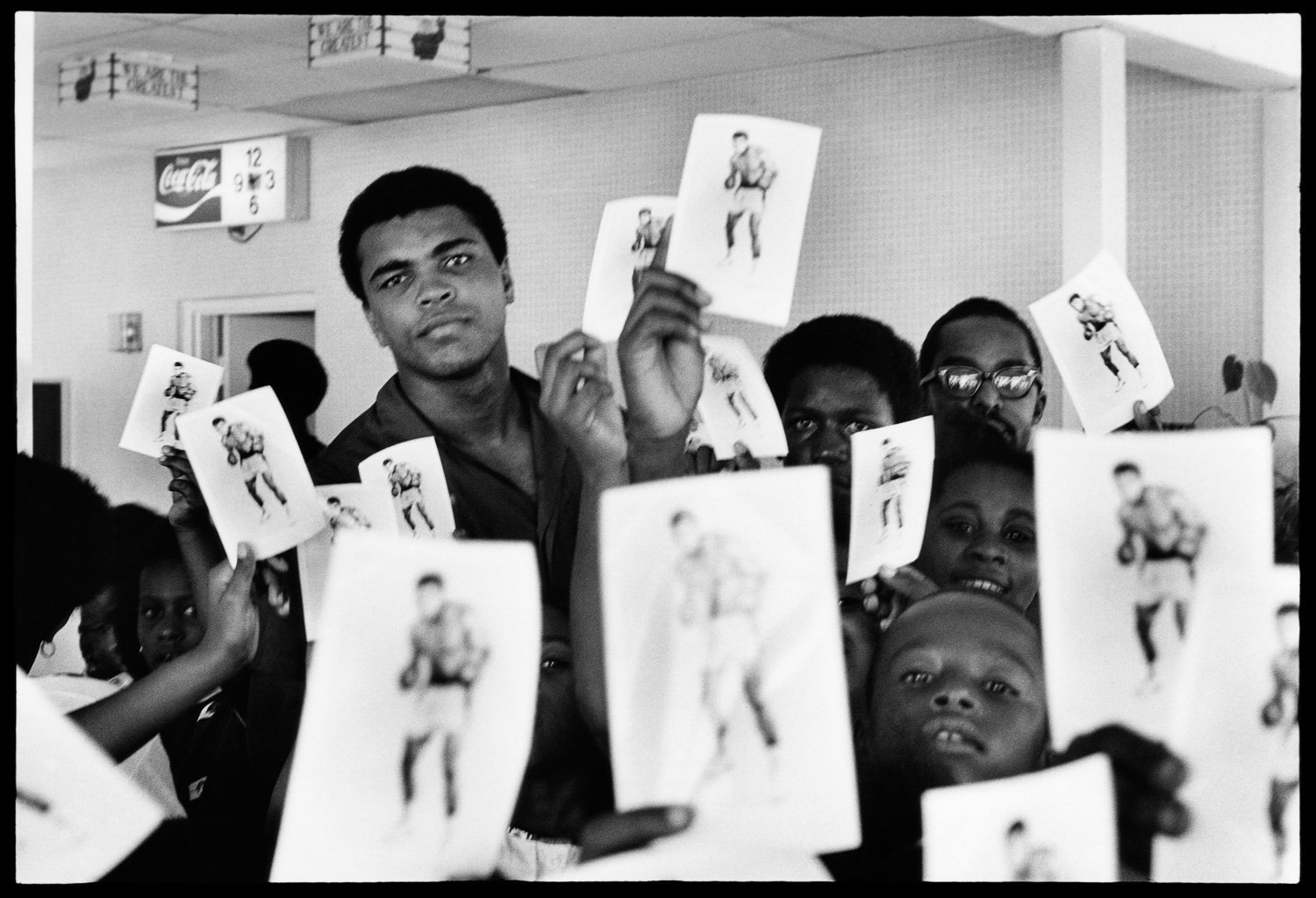

Few photographers have captured the experience of being Black in a hostile, changing mid-century America as famously – or indeed, with such tender clarity – as Gordon Parks. This year, alongside an exhibition at Jack Shainman in New York, a new book revisits Park’s seminal photographs and essays recorded between the years of 1963 and 1970 for Life magazine. “On a scholarly and theoretical level, the book has provided space to consider the various meanings and debates about what it means to be Black, and Blackness as a political, philosophical, and aesthetic category,” writes scholar Nicole R Fleetwood in the book, which uniquely reveals, alongside photography, how Parks’ writing was “the most personal and intimate form of expression throughout his life”.

Read our feature on the series here.

Jack Luders-Booth’s Women Prison Polaroids presents a moving portrait of life at MCI Framingham, a correctional facility in Boston where the 88-year-old Harvard professor taught photography to inmates throughout the 1970s. Only revisited this year with the help of London publisher Stanley/Barker, the book pairs gentle portraits with personal accounts of inmates’ stories recorded during his time there, casting a sympathetic gaze upon women who have found themselves in very difficult circumstances. “The women were compelling in many ways; their backgrounds, their assertion of certain values,” he told AnOther. “I had no idea what a prison was like and I was actually scared when I first went, but it’s like so much in life – the more you [become acquainted with] something, the more normal it becomes.”

Read our feature on the series here.

A follow-up to his acclaimed debut photo book I can’t stand to see you cry, Rahim Fortune’s Hardtack uses the Civil-war era survival food of the same name – a dry, unleavened cracker – as a metaphor for the resilient nature of Black culture in the American South. Mixing striking portraits of coming-of-age traditions with sweeping landscapes, the resulting book forms a reflective portrait of place, community and identity. “I became really interested in this idea of self-creation through clothing,” says Fortune. “Especially within the wake of this country’s current political moment. What does it mean for a Black Southern identity?”

Read our feature on the series here.

Buck Ellison’s fourth book with IDEA explores the “security and violence of whiteness” in upper-class America. Capturing a group of affluent young people at a ski resort, at first glance, his crisp, staged scenes seem to simply present a world of leisure and banality. Look closer at the dynastic poses and expensive personal artefacts Ellison captures, though, and complicated threads of colonialism, power and privilege that stretch back through history will start to unravel. “I use empathy as a tool for getting towards the truth,” he said. “I don’t think we need any more images in the world that tell us that people on the right wing are bad, or that they’re monsters. Because I think what’s scarier is that we have more in common with them than we might like to think.”

Read our feature on the series here.

Famed for his ecstatically poised portraits, South African photographer Pieter Hugo has spent his career photographing fringe communities in series that have both garnered acclaim and courted controversy. His latest work, Californian Wildflowers, documents the homeless communities that reside in the Tenderloin neighbourhood of San Francisco. Displayed in an exhibition at Jonathan Carver Moore Gallery and published in an accompanying monograph by TBW Books, the project shines a vibrant and dignified light upon victims of the 2008 recession, war veterans, and individuals suffering with mental health illnesses in one of the richest cities in America.

Read our feature on the series here.

Beth Garrabrant’s most famous photos are of Taylor Swift, who the Illinois-born artist has shot several album covers and promo shots for over the past few years. Her personal work, however, takes on a subtler inquisitive quality. Exploring what it means to be on the precipice of adulthood in America, her debut book documents young people up and down the country in semi-staged scenes of idleness and energy in schools, churches, kitchens and bedrooms. The culmination of two decades of work, the book draws upon memories of her own youth in Lake Forest, where the king of 1980s teen cinema John Huges also grew up. “It is mostly me trying to recreate scenes that I remember from growing up,” she told AnOther. “These quiet scenes, these kinds of tropes, almost silences, that were very familiar to me.”

Read our feature on the series here.

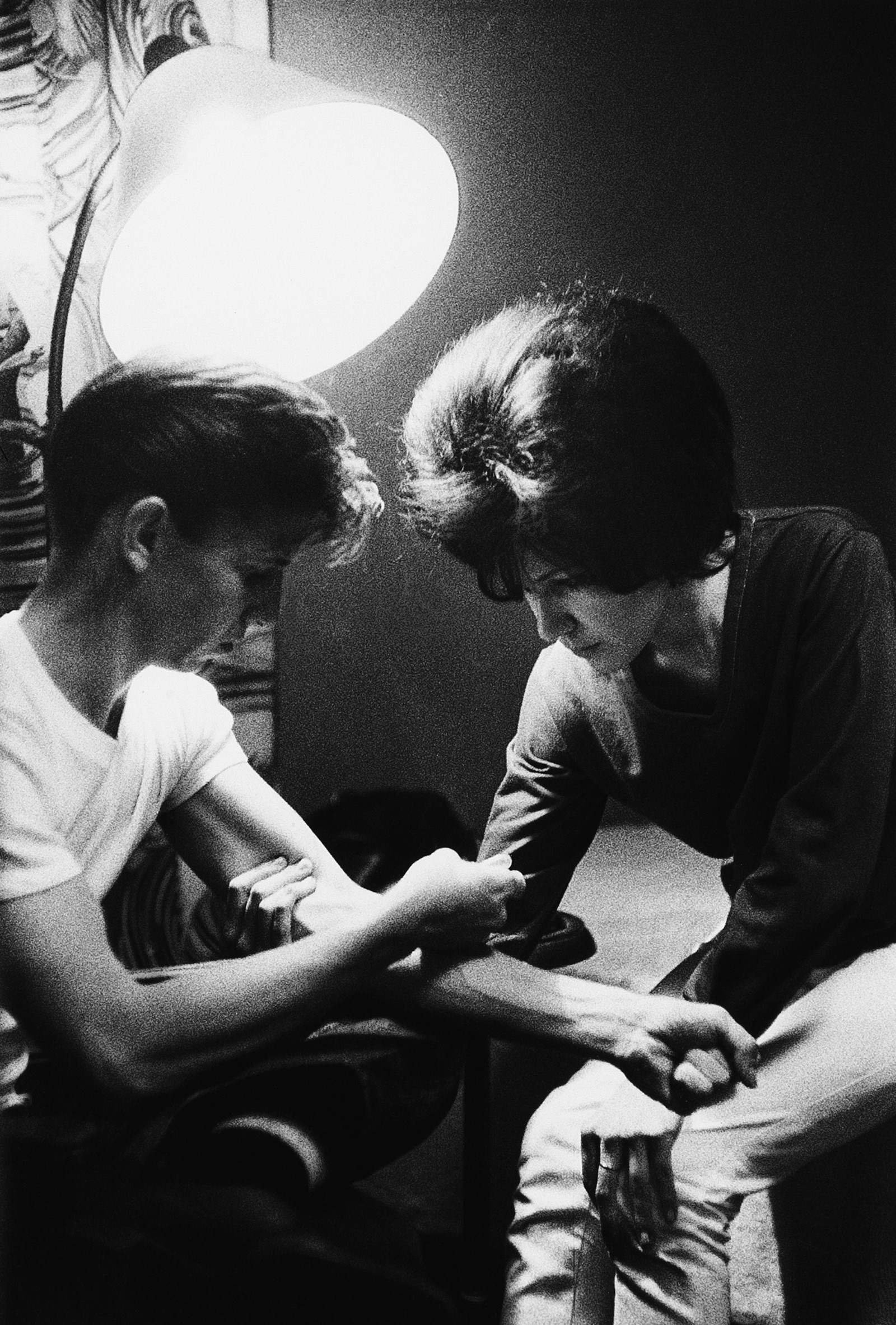

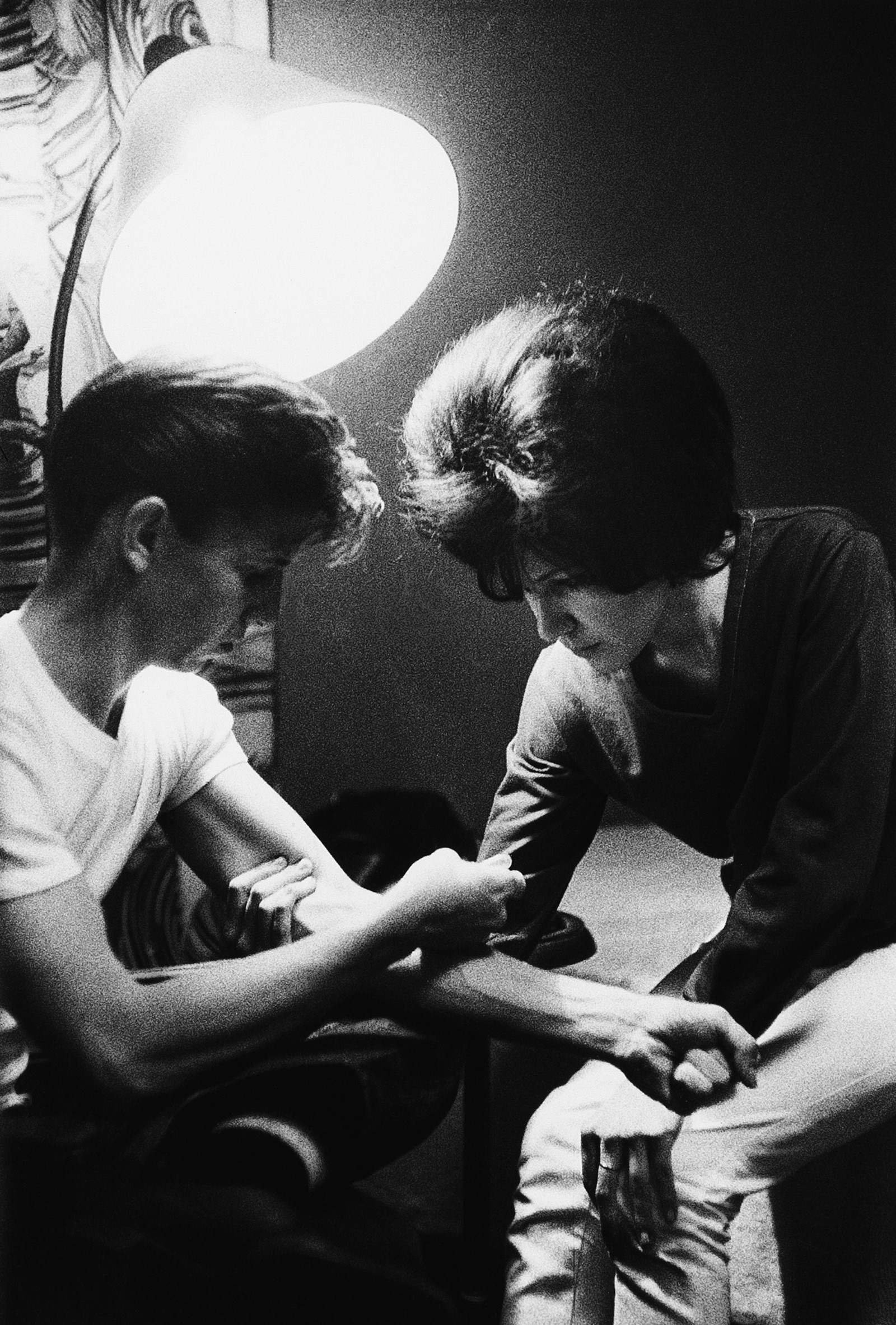

Larry Clark’s Return sees the cult artist wind the tape back 50 years, revisiting shots from his infamous 1971 book, Tulsa. In images that are both intimate and difficult to look at, Clark turns the camera on himself and his social circle as they descend into a life of drugs, forming a raw portrait of disenfranchised suburban youth captured from within. “I photographed my friends over a ten-year period in this secret world that nobody else could have possibly come in and done except someone from the inside,” he says. “ When I started making work, I said, ‘Why can’t you show everything?’”

Read our feature on the series here.

Coinciding with her landmark show at Jeau de Paume in Paris – the artist’s first retrospective in Europe – Tina Barney’s Family Ties provides a piercing immersion into four decades of East Coast American wealth. A descendant of the Lehman family who grew up surrounded by art, Barney’s crisp tableaux shots provide a window into a world she has both inhabited and questioned, filling huge institutions like MoMA and influencing filmmakers like Sofia Coppola. “I really wanted to show how much I cared about my existence,” she told AnOther. “I cared about every living inch that I was surrounded by, that I was born into. And I felt that it had to be marked.”

Read our feature on the series here.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageGregory Crewdson, Untitled, From the series: Twilight , 1998-2002. Digital pigment print The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna, Permanent loan – Private Collection © Gregory Crewdson

America is an endlessly fascinating place shaped by the vastness and volatility of its extremes. It’s the only country that houses all five of Earth’s climates; a place where you can visit tropical beaches, dusty deserts and freezing cold mountains without ever technically leaving its borders. It’s at the vanguard of progressive visual arts and Western technological invention, home to the world’s highest concentration of billionaires and some of the most vibrant metropolitan cities. On the flip side of the coin, it’s also a place where appalling hate-driven violence runs rampant, punitive law systems have led to the world’s biggest prison population, and poverty deepens as the 1% grows richer. It’s a place of freedom and frustration, dreams and desperation, and – whether we like it or not – when it sneezes, the rest of the world braces itself for whatever cold, or indeed worse, might spread in suit.

Just a few weeks into Trump’s second landslide bid for presidency, times have never felt more heightened or surreal across the pond. As the year closes out, it feels like a pertinent moment to reflect on the best photo stories of American life published on AnOther this year. There are journeys into the hidden archives of government organisations, Polaroids taken in women’s prisons, and vital portraits of Black life during the 1960s. There are surreal visions of modern suburbia, lavish portrayals of East Coast wealth and heartwarming portrayals of teenagers coming of age. Looking back at the country’s complex history while asking what it means to be an American today, together, these photo series form a tapestry of experience, culture and feeling as varied as its 50 states.

Below, read more about ten American photo projects featured on AnOther in 2024.

Considered by many to be one of the most important photography books ever made, Larry Sultan and Mike Madel’s 1977 Evidence is the product of two years spent sifting through the archives of American government agencies and corporations. Gathering shadowy happenings inside laboratories, police stations, state departments, and offices of corporations, the pair sequenced these unearthed images without written context, forcing the viewer to cobble together meaning themselves. “It was clear to us at that time that these organisations were not giving us the wonderful future that they promised,” Mandel told AnOther upon the book’s republishing. “We knew these pictures of these strange translations of the landscape, or these clinical, objectifying images were a dystopian opportunity for us to create that message.”

Read our feature on the series here.

Drawing upon the menacing cinematic worlds of David Lynch and Alfred Hitchcock, Gregory Crewdson’s photographs of suburban America will make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up. The Massachusetts-born photographer has spent the past 25 years orchestrating wide-angled scenes of domestic darkness, where characters are frozen in thriller-like tableaus shot in humdrum houses and grey tree-lined streets. A new Prestel book brings together ten of his most acclaimed series, offering a comprehensive journey into his psychological photographic universe. “For me, everything begins and ends with Hitchcock’s movies,” he told AnOther. “I’m primarily interested in art – not only movies but paintings, photography, literature – that finds something extraordinary in everyday life.”

Read our feature on the series here.st-block-28

Few photographers have captured the experience of being Black in a hostile, changing mid-century America as famously – or indeed, with such tender clarity – as Gordon Parks. This year, alongside an exhibition at Jack Shainman in New York, a new book revisits Park’s seminal photographs and essays recorded between the years of 1963 and 1970 for Life magazine. “On a scholarly and theoretical level, the book has provided space to consider the various meanings and debates about what it means to be Black, and Blackness as a political, philosophical, and aesthetic category,” writes scholar Nicole R Fleetwood in the book, which uniquely reveals, alongside photography, how Parks’ writing was “the most personal and intimate form of expression throughout his life”.

Read our feature on the series here.

Jack Luders-Booth’s Women Prison Polaroids presents a moving portrait of life at MCI Framingham, a correctional facility in Boston where the 88-year-old Harvard professor taught photography to inmates throughout the 1970s. Only revisited this year with the help of London publisher Stanley/Barker, the book pairs gentle portraits with personal accounts of inmates’ stories recorded during his time there, casting a sympathetic gaze upon women who have found themselves in very difficult circumstances. “The women were compelling in many ways; their backgrounds, their assertion of certain values,” he told AnOther. “I had no idea what a prison was like and I was actually scared when I first went, but it’s like so much in life – the more you [become acquainted with] something, the more normal it becomes.”

Read our feature on the series here.

A follow-up to his acclaimed debut photo book I can’t stand to see you cry, Rahim Fortune’s Hardtack uses the Civil-war era survival food of the same name – a dry, unleavened cracker – as a metaphor for the resilient nature of Black culture in the American South. Mixing striking portraits of coming-of-age traditions with sweeping landscapes, the resulting book forms a reflective portrait of place, community and identity. “I became really interested in this idea of self-creation through clothing,” says Fortune. “Especially within the wake of this country’s current political moment. What does it mean for a Black Southern identity?”

Read our feature on the series here.

Buck Ellison’s fourth book with IDEA explores the “security and violence of whiteness” in upper-class America. Capturing a group of affluent young people at a ski resort, at first glance, his crisp, staged scenes seem to simply present a world of leisure and banality. Look closer at the dynastic poses and expensive personal artefacts Ellison captures, though, and complicated threads of colonialism, power and privilege that stretch back through history will start to unravel. “I use empathy as a tool for getting towards the truth,” he said. “I don’t think we need any more images in the world that tell us that people on the right wing are bad, or that they’re monsters. Because I think what’s scarier is that we have more in common with them than we might like to think.”

Read our feature on the series here.

Famed for his ecstatically poised portraits, South African photographer Pieter Hugo has spent his career photographing fringe communities in series that have both garnered acclaim and courted controversy. His latest work, Californian Wildflowers, documents the homeless communities that reside in the Tenderloin neighbourhood of San Francisco. Displayed in an exhibition at Jonathan Carver Moore Gallery and published in an accompanying monograph by TBW Books, the project shines a vibrant and dignified light upon victims of the 2008 recession, war veterans, and individuals suffering with mental health illnesses in one of the richest cities in America.

Read our feature on the series here.

Beth Garrabrant’s most famous photos are of Taylor Swift, who the Illinois-born artist has shot several album covers and promo shots for over the past few years. Her personal work, however, takes on a subtler inquisitive quality. Exploring what it means to be on the precipice of adulthood in America, her debut book documents young people up and down the country in semi-staged scenes of idleness and energy in schools, churches, kitchens and bedrooms. The culmination of two decades of work, the book draws upon memories of her own youth in Lake Forest, where the king of 1980s teen cinema John Huges also grew up. “It is mostly me trying to recreate scenes that I remember from growing up,” she told AnOther. “These quiet scenes, these kinds of tropes, almost silences, that were very familiar to me.”

Read our feature on the series here.

Larry Clark’s Return sees the cult artist wind the tape back 50 years, revisiting shots from his infamous 1971 book, Tulsa. In images that are both intimate and difficult to look at, Clark turns the camera on himself and his social circle as they descend into a life of drugs, forming a raw portrait of disenfranchised suburban youth captured from within. “I photographed my friends over a ten-year period in this secret world that nobody else could have possibly come in and done except someone from the inside,” he says. “ When I started making work, I said, ‘Why can’t you show everything?’”

Read our feature on the series here.

Coinciding with her landmark show at Jeau de Paume in Paris – the artist’s first retrospective in Europe – Tina Barney’s Family Ties provides a piercing immersion into four decades of East Coast American wealth. A descendant of the Lehman family who grew up surrounded by art, Barney’s crisp tableaux shots provide a window into a world she has both inhabited and questioned, filling huge institutions like MoMA and influencing filmmakers like Sofia Coppola. “I really wanted to show how much I cared about my existence,” she told AnOther. “I cared about every living inch that I was surrounded by, that I was born into. And I felt that it had to be marked.”

Read our feature on the series here.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.