Rewrite

Suffering from postpartum anxiety, filmmaker Elizabeth Sankey found that watching witches on screen became a way to connect with other women’s pain. Here, she opens up about her favourite films

Elizabeth Sankey’s Witches is one of the year’s most potent and thought-provoking documentary films. It begins compellingly enough as a captivating visual essay on the portrayal of witchcraft on screen in films both iconic (The Wizard of Oz) and cult (The Craft, Girl, Interrupted). Sankey has form here, having showcased a rare ability to contextualise even very familiar movies with 2019’s Romantic Comedy, an affectionate documentary featuring clips from hundreds of rom-coms.

But Witches quickly morphs into something quite different: a harrowing but profoundly moving account of Sankey’s experience with severe postpartum anxiety after giving birth to her son in 2020. Sankey recalls being admitted to a mother-and-baby psychiatric ward, a place she initially found terrifying, but later became a “safe place” where she could bond with her son and draw strength from other women who were also suffering.

Her film continues to interrogate the connections between postpartum mental health and the way witches have been portrayed in western pop culture through interviews with medical professionals, historians and other women who’ve experienced what is often dismissed as mere ‘baby blues’. Throughout, clips from dozens of witch-centric films are used to punctuate and illuminate Sankey’s points.

“This project started off as a way of understanding what happened to me and making peace with it,” Sankey says. “And watching lots of women behaving badly and being ‘difficult’ [in films] really soothed me during that time, because there’s so much bombardment on women to be a very specific type of woman, and I felt like I had failed at that completely.” But as she delved deeper into the subject, Sankey realised her film had a “bigger and deeper” purpose. “I wanted to have as many women as possible telling their stories because that had been so helpful to me when I was ill,” she says. “It really made me feel less alone, so I wanted to pass that on.” The result is an empathetic and revelatory film that will spark important conversations about the way we talk about and treat postpartum mental illness.

Below, Elizabeth Sankey picks five films that played a pivotal role in helping her make Witches.

“The craft of this film is incredible, but I also love that it gives such a clear depiction of good and bad. L Frank Baum [who wrote the book it’s adapted from] based the character of Glinda on his mother-in-law, Matilda Joslyn Gage, who was this very amazing proto-feminist woman. She was one of the first people to say that women who had been persecuted during the witch trials weren’t actually witches, but women who had issues, or healers and midwives, or women living on the outsides of society. When he based Glinda on her, he sort of unwillingly or unknowingly began this idea of there being good and bad when it comes to witches, and therefore when it comes to women. For that reason, it’s a really important film.”

“This is like a romantic comedy with a very strange premise. Veronica Lake plays a witch burned at the stake in Salem in the 1600s who gets brought back from the dead in the 1940s. She wants to get revenge on the descendant of the witchfinder who killed her, but ends up falling in love with him instead. He’s also a politician so she uses her powers to help him win an election – like I say, it’s very strange. The film ends with her saying, ‘I won’t use my powers any more,’ which is a bit annoying, but Veronica Lake is absolutely stunning in it: just so weird, funny and sexy. There’s also an Italian remake [1980’s Mia Moglie è una Strega] where they let the witch keep her powers at the end.”

“This must be one of the first films that portrays a psychiatric ward. Olivia de Havilland plays a woman who is put into one and can’t remember who she is; most of the film is just her internal monologue. It still feels so prescient because so little has changed in terms of the way that psychiatric wards look and the way it feels to be in one. There’s a brilliant bit where she goes to a sort of board meeting with all the doctors who are deciding what to do with her. That’s a really scary thing, because your liberty is at stake – it’s something I felt when I was in the [mother-and-baby psychiatric] ward and had weekly meetings with the team. The majority of them were really lovely women, but you do just sit there while they’re discussing you and how long you’re going to be there for.”

“This film is amazing but also really problematic – I think the director [Andrzej Żuławski] based it on the breakdown of his own relationship. Isabelle Adjani plays two characters: this perfect, pretty school teacher who is very loving and gentle, and this evil ex-wife who is completely unhinged and having a relationship with an actual monster. Madness is often seen, especially in women, as something that is scary but also kind of weak. But there’s something really powerful about the way [the protagonist’s] madness is portrayed in this film, which unlocked something for me when I was making Witches. It made me realise there’s power and beauty in embracing all that darkness and rage and witchiness.”

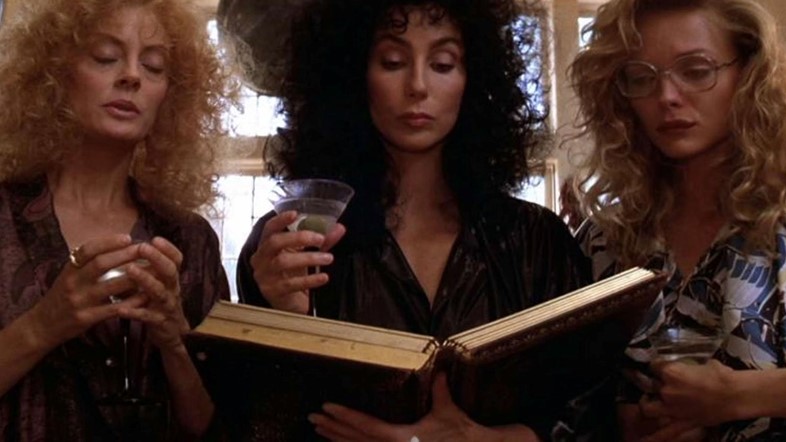

“I’m always really surprised when people haven’t seen The Witches of Eastwick because I think it’s a perfect film. It’s got big 80s hair and a mindblowing cast: three brilliant female leads [Cher, Michelle Pfeiffer and Susan Sarandon] plus Jack Nicholson. I also love the fact it takes place in this very puritanical Massachusetts town, which is a world I find really beautiful and want to spend time in. Seeing the witches really embrace their power and their potency, and for the film not to end with them having that power stripped away, is just so refreshing. It’s also really funny!”

Witches is available to stream on MUBI UK now.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Suffering from postpartum anxiety, filmmaker Elizabeth Sankey found that watching witches on screen became a way to connect with other women’s pain. Here, she opens up about her favourite films

Elizabeth Sankey’s Witches is one of the year’s most potent and thought-provoking documentary films. It begins compellingly enough as a captivating visual essay on the portrayal of witchcraft on screen in films both iconic (The Wizard of Oz) and cult (The Craft, Girl, Interrupted). Sankey has form here, having showcased a rare ability to contextualise even very familiar movies with 2019’s Romantic Comedy, an affectionate documentary featuring clips from hundreds of rom-coms.

But Witches quickly morphs into something quite different: a harrowing but profoundly moving account of Sankey’s experience with severe postpartum anxiety after giving birth to her son in 2020. Sankey recalls being admitted to a mother-and-baby psychiatric ward, a place she initially found terrifying, but later became a “safe place” where she could bond with her son and draw strength from other women who were also suffering.

Her film continues to interrogate the connections between postpartum mental health and the way witches have been portrayed in western pop culture through interviews with medical professionals, historians and other women who’ve experienced what is often dismissed as mere ‘baby blues’. Throughout, clips from dozens of witch-centric films are used to punctuate and illuminate Sankey’s points.

“This project started off as a way of understanding what happened to me and making peace with it,” Sankey says. “And watching lots of women behaving badly and being ‘difficult’ [in films] really soothed me during that time, because there’s so much bombardment on women to be a very specific type of woman, and I felt like I had failed at that completely.” But as she delved deeper into the subject, Sankey realised her film had a “bigger and deeper” purpose. “I wanted to have as many women as possible telling their stories because that had been so helpful to me when I was ill,” she says. “It really made me feel less alone, so I wanted to pass that on.” The result is an empathetic and revelatory film that will spark important conversations about the way we talk about and treat postpartum mental illness.

Below, Elizabeth Sankey picks five films that played a pivotal role in helping her make Witches.

“The craft of this film is incredible, but I also love that it gives such a clear depiction of good and bad. L Frank Baum [who wrote the book it’s adapted from] based the character of Glinda on his mother-in-law, Matilda Joslyn Gage, who was this very amazing proto-feminist woman. She was one of the first people to say that women who had been persecuted during the witch trials weren’t actually witches, but women who had issues, or healers and midwives, or women living on the outsides of society. When he based Glinda on her, he sort of unwillingly or unknowingly began this idea of there being good and bad when it comes to witches, and therefore when it comes to women. For that reason, it’s a really important film.”

“This is like a romantic comedy with a very strange premise. Veronica Lake plays a witch burned at the stake in Salem in the 1600s who gets brought back from the dead in the 1940s. She wants to get revenge on the descendant of the witchfinder who killed her, but ends up falling in love with him instead. He’s also a politician so she uses her powers to help him win an election – like I say, it’s very strange. The film ends with her saying, ‘I won’t use my powers any more,’ which is a bit annoying, but Veronica Lake is absolutely stunning in it: just so weird, funny and sexy. There’s also an Italian remake [1980’s Mia Moglie è una Strega] where they let the witch keep her powers at the end.”

“This must be one of the first films that portrays a psychiatric ward. Olivia de Havilland plays a woman who is put into one and can’t remember who she is; most of the film is just her internal monologue. It still feels so prescient because so little has changed in terms of the way that psychiatric wards look and the way it feels to be in one. There’s a brilliant bit where she goes to a sort of board meeting with all the doctors who are deciding what to do with her. That’s a really scary thing, because your liberty is at stake – it’s something I felt when I was in the [mother-and-baby psychiatric] ward and had weekly meetings with the team. The majority of them were really lovely women, but you do just sit there while they’re discussing you and how long you’re going to be there for.”

“This film is amazing but also really problematic – I think the director [Andrzej Żuławski] based it on the breakdown of his own relationship. Isabelle Adjani plays two characters: this perfect, pretty school teacher who is very loving and gentle, and this evil ex-wife who is completely unhinged and having a relationship with an actual monster. Madness is often seen, especially in women, as something that is scary but also kind of weak. But there’s something really powerful about the way [the protagonist’s] madness is portrayed in this film, which unlocked something for me when I was making Witches. It made me realise there’s power and beauty in embracing all that darkness and rage and witchiness.”

“I’m always really surprised when people haven’t seen The Witches of Eastwick because I think it’s a perfect film. It’s got big 80s hair and a mindblowing cast: three brilliant female leads [Cher, Michelle Pfeiffer and Susan Sarandon] plus Jack Nicholson. I also love the fact it takes place in this very puritanical Massachusetts town, which is a world I find really beautiful and want to spend time in. Seeing the witches really embrace their power and their potency, and for the film not to end with them having that power stripped away, is just so refreshing. It’s also really funny!”

Witches is available to stream on MUBI UK now.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.