Rewrite

An emotional meditation on innocence and memory, Jesse Gouveia’s new photo show captures a series of childhood forts, painstakingly remade in adulthood

For his debut solo exhibition, American photographer Jesse Gouveia seized on a type of patterned cloth so ubiquitous in Western homes and wardrobes that its symbolism is often overlooked: plaid. Deriving its name from the early 16th-century Gaelic plaide, meaning ‘blanket’, plaid was the name given by British and American manufacturers when they started replicating tartan print from Scotland, plunging it into the mainstream. A shapeshifting pattern that has since cropped up just about everywhere, from the plaid flannel shirts popularised by grunge icon Kurt Cobain in the 90s to the acrid yellow Dolce & Gabbana suit worn by Alicia Silverstone in Clueless – and most recently, the break-the-internet S/S23 Bottega Veneta trompe-l’œil plaid shirt donned by Kate Moss simply with a white tank and blue jeans on the runway – plaid means something different to everyone, with its connotations of tradition, rebellion and comfort.

Gouveia’s show, held at New York’s Anonymous Gallery and simply titled Plaid, focuses on the self-taught photographer’s own memories of the material. “Plaid is this pattern that just kept showing up in my childhood,” he says, speaking from his peaceful studio in NoHo, Manhattan. “It was like this comfort pattern for me – it was the blankets that we slept on as kids, the shirts, scarves and anything that was soft. It reminds me of my family and also just reminds me of how consistency in anything casts an emotional mould in our design.”

Although the material provided the conceptual impetus behind the show, Plaid focuses on Gouveia’s childhood forts instead, with plaid appearing in just two of four frames. After looking through old family photographs and finding images of the forts he made during his childhood in Seattle (he is now based in New York), Gouveia began to create the new series. “I started thinking about how interesting the old forts were in retrospect,” he recalls. “And then I thought, ‘Well, I wonder how they would look if I made these again as an adult man.’”

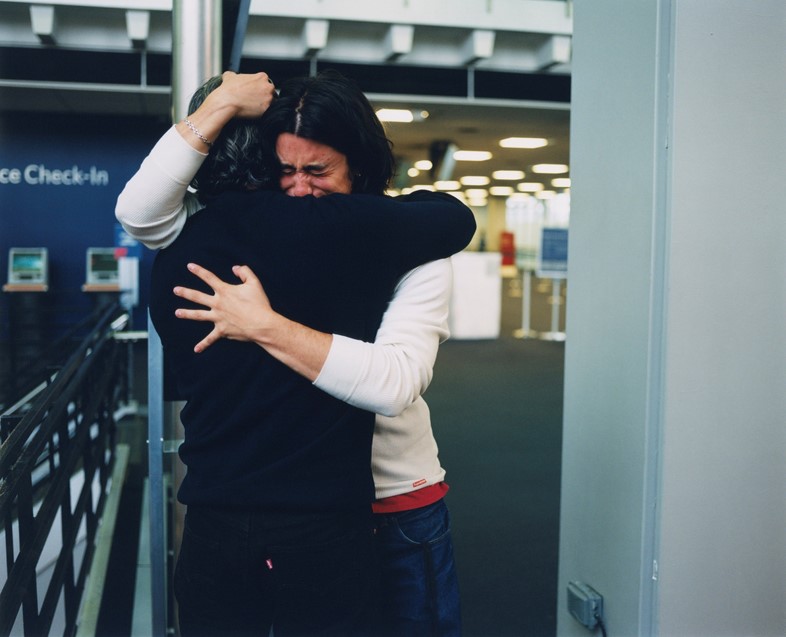

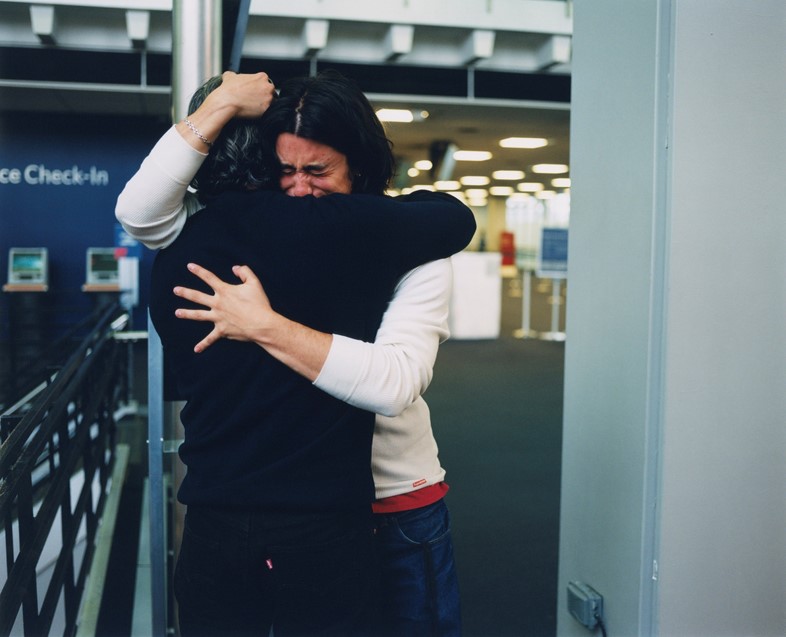

Most of Gouveia’s photographs are autobiographical, grappling with memory, emotion and family history. Saying Goodbye, a self-portrait which featured in a group show about American-ness at Anonymous Gallery, captured Gouveia hugging his father tightly in an airport terminal, sobbing; Patience of Repair, another self-portrait, shows the photographer sat stoic on a sofa littered with pillows, pressing an ice pack to his ankle and scrunching up a pillow in what we can assume is pain (before becoming a photographer, Gouveia had a snowboarding career for a decade). “A lot of my work is about how we relay memory, and how memory abstracts,” he explains. “I tend to use the words recreation or reconstruction quite often [with my work], because our idea of ourselves is accumulated through memory.”

Much of the work has an introspective air of stillness and cosiness to it, with solitary figures situated in domestic settings, reclining on beds, sofas, or simply standing, shoes off and socks on. Blue is a colour that appears often, whether in objects – a blow-up mattress, a balloon – clothes, or the general grade of the image (symbolically speaking, blue represents tranquility, sadness and truth – all things that are relevant to the work). When we meet in person, Gouveia is even wearing a T-shirt in a vibrant cobalt blue.

Alongside his personal work, Gouveia also shoots editorials for fashion magazines; his most famous image, a cover for HTSI, captured Frank Ocean in a white T-shirt, cap and slick black leather trousers, holding up a Paper-mâché model of a dog’s head. Another cover for HTSI saw Pharrell Williams sitting atop a black plaid Japanese floor cushion – the material crops up here again – made by his brother, Myles Gouveia for his brand Zabu, which, like Jesse’s work, is inspired by childhood rituals.

But in Plaid, for the first time ever, people do not feature in Gouveia’s images. Instead, the four photos in the show capture childhood forts remade painstakingly by Gouveia in adulthood, made over a period of four years; there’s a fort constructed of white sheets and duvets in his parent’s living room, a remarkable mishmash of branches in an autumnal forest littered with leaves, an igloo with the last embers of a dying fire inside, smoke rising off the top, and a structure made out of driftwood on a black-sand beach, a blue plaid shirt draped over its exterior.

Gouveia has always worked more like a fine artist than a photographer, preferring to create images slowly and introspectively instead of churning them out and posting them in a constant stream online. Plaid heralds his arrival as both a photographer and a sculptor; like the British artist Andy Goldsworthy, Gouveia made his extraordinary, delicate structures in the wild and photographed them for a mass audience to consume. There is also one three-dimensional sculpture in the show, an abstract white doorframe where light slowly fills up the frame on a loop; a metaphor for “pillars of memory”, the light acts as a visual stand-in for the childhood ritual of marking one’s height out on the doorframe in black pen.

Along with old photos from his own personal life, Gouveia cites cinema and sculpture as his main sources of inspiration; he adores the slow, contemplative films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Memoria), Edward Yang (Yi Yi) and Alejandro González Iñárritu (Babel, Birdman) thanks to their penchant for long stretches of silence; just like Gouveia’s work, these films “leave a lot of open space to think”. He’s also a fan of American sculptor Michael E Smith, who transforms everyday objects into unsettling, rotting ensembles. “Almost all of the work I found the most honest wasn’t photography,” he says. “I was drawn to things that came from experience. I feel the most connected making work that is coming from somewhere I can rehearse.”

Printed life-size on the four walls of the gallery, the photographs of the forts are designed to be immersive and inviting; Gouveia wants the viewer to spend time noticing all the small details in them (orange peel strewn on the snow outside the igloo, a flickering lantern on the beach, a giant carp windsock – koinobori – hanging inside the fort in his parents’ living room, a subtle nod to his Japanese heritage). Remarkable in their sense of imagination and scale, the photographs in Plaid are ripe for interpretation; it’s up for debate whether they are about the loss of childhood innocence or innocence regained. Looking at the works, though, it’s hard to resist the urge to clamber inside, tuck in, and let your imagination run wild.

Plaid by Jesse Gouveia is on show at Anonymous Gallery in New York until 21 December 2024.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

An emotional meditation on innocence and memory, Jesse Gouveia’s new photo show captures a series of childhood forts, painstakingly remade in adulthood

For his debut solo exhibition, American photographer Jesse Gouveia seized on a type of patterned cloth so ubiquitous in Western homes and wardrobes that its symbolism is often overlooked: plaid. Deriving its name from the early 16th-century Gaelic plaide, meaning ‘blanket’, plaid was the name given by British and American manufacturers when they started replicating tartan print from Scotland, plunging it into the mainstream. A shapeshifting pattern that has since cropped up just about everywhere, from the plaid flannel shirts popularised by grunge icon Kurt Cobain in the 90s to the acrid yellow Dolce & Gabbana suit worn by Alicia Silverstone in Clueless – and most recently, the break-the-internet S/S23 Bottega Veneta trompe-l’œil plaid shirt donned by Kate Moss simply with a white tank and blue jeans on the runway – plaid means something different to everyone, with its connotations of tradition, rebellion and comfort.

Gouveia’s show, held at New York’s Anonymous Gallery and simply titled Plaid, focuses on the self-taught photographer’s own memories of the material. “Plaid is this pattern that just kept showing up in my childhood,” he says, speaking from his peaceful studio in NoHo, Manhattan. “It was like this comfort pattern for me – it was the blankets that we slept on as kids, the shirts, scarves and anything that was soft. It reminds me of my family and also just reminds me of how consistency in anything casts an emotional mould in our design.”

Although the material provided the conceptual impetus behind the show, Plaid focuses on Gouveia’s childhood forts instead, with plaid appearing in just two of four frames. After looking through old family photographs and finding images of the forts he made during his childhood in Seattle (he is now based in New York), Gouveia began to create the new series. “I started thinking about how interesting the old forts were in retrospect,” he recalls. “And then I thought, ‘Well, I wonder how they would look if I made these again as an adult man.’”

Most of Gouveia’s photographs are autobiographical, grappling with memory, emotion and family history. Saying Goodbye, a self-portrait which featured in a group show about American-ness at Anonymous Gallery, captured Gouveia hugging his father tightly in an airport terminal, sobbing; Patience of Repair, another self-portrait, shows the photographer sat stoic on a sofa littered with pillows, pressing an ice pack to his ankle and scrunching up a pillow in what we can assume is pain (before becoming a photographer, Gouveia had a snowboarding career for a decade). “A lot of my work is about how we relay memory, and how memory abstracts,” he explains. “I tend to use the words recreation or reconstruction quite often [with my work], because our idea of ourselves is accumulated through memory.”

Much of the work has an introspective air of stillness and cosiness to it, with solitary figures situated in domestic settings, reclining on beds, sofas, or simply standing, shoes off and socks on. Blue is a colour that appears often, whether in objects – a blow-up mattress, a balloon – clothes, or the general grade of the image (symbolically speaking, blue represents tranquility, sadness and truth – all things that are relevant to the work). When we meet in person, Gouveia is even wearing a T-shirt in a vibrant cobalt blue.

Alongside his personal work, Gouveia also shoots editorials for fashion magazines; his most famous image, a cover for HTSI, captured Frank Ocean in a white T-shirt, cap and slick black leather trousers, holding up a Paper-mâché model of a dog’s head. Another cover for HTSI saw Pharrell Williams sitting atop a black plaid Japanese floor cushion – the material crops up here again – made by his brother, Myles Gouveia for his brand Zabu, which, like Jesse’s work, is inspired by childhood rituals.

But in Plaid, for the first time ever, people do not feature in Gouveia’s images. Instead, the four photos in the show capture childhood forts remade painstakingly by Gouveia in adulthood, made over a period of four years; there’s a fort constructed of white sheets and duvets in his parent’s living room, a remarkable mishmash of branches in an autumnal forest littered with leaves, an igloo with the last embers of a dying fire inside, smoke rising off the top, and a structure made out of driftwood on a black-sand beach, a blue plaid shirt draped over its exterior.

Gouveia has always worked more like a fine artist than a photographer, preferring to create images slowly and introspectively instead of churning them out and posting them in a constant stream online. Plaid heralds his arrival as both a photographer and a sculptor; like the British artist Andy Goldsworthy, Gouveia made his extraordinary, delicate structures in the wild and photographed them for a mass audience to consume. There is also one three-dimensional sculpture in the show, an abstract white doorframe where light slowly fills up the frame on a loop; a metaphor for “pillars of memory”, the light acts as a visual stand-in for the childhood ritual of marking one’s height out on the doorframe in black pen.

Along with old photos from his own personal life, Gouveia cites cinema and sculpture as his main sources of inspiration; he adores the slow, contemplative films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Memoria), Edward Yang (Yi Yi) and Alejandro González Iñárritu (Babel, Birdman) thanks to their penchant for long stretches of silence; just like Gouveia’s work, these films “leave a lot of open space to think”. He’s also a fan of American sculptor Michael E Smith, who transforms everyday objects into unsettling, rotting ensembles. “Almost all of the work I found the most honest wasn’t photography,” he says. “I was drawn to things that came from experience. I feel the most connected making work that is coming from somewhere I can rehearse.”

Printed life-size on the four walls of the gallery, the photographs of the forts are designed to be immersive and inviting; Gouveia wants the viewer to spend time noticing all the small details in them (orange peel strewn on the snow outside the igloo, a flickering lantern on the beach, a giant carp windsock – koinobori – hanging inside the fort in his parents’ living room, a subtle nod to his Japanese heritage). Remarkable in their sense of imagination and scale, the photographs in Plaid are ripe for interpretation; it’s up for debate whether they are about the loss of childhood innocence or innocence regained. Looking at the works, though, it’s hard to resist the urge to clamber inside, tuck in, and let your imagination run wild.

Plaid by Jesse Gouveia is on show at Anonymous Gallery in New York until 21 December 2024.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.