Rewrite

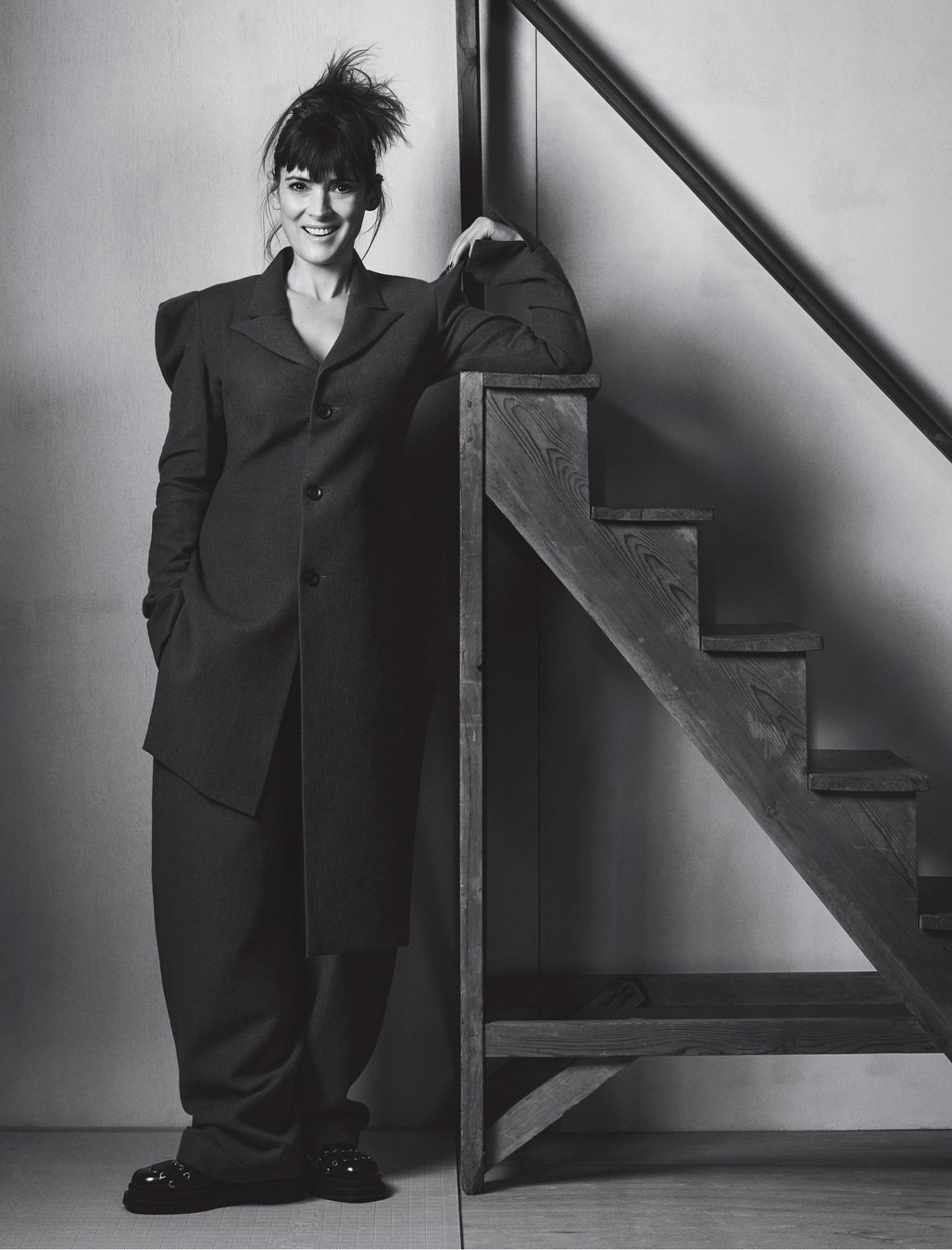

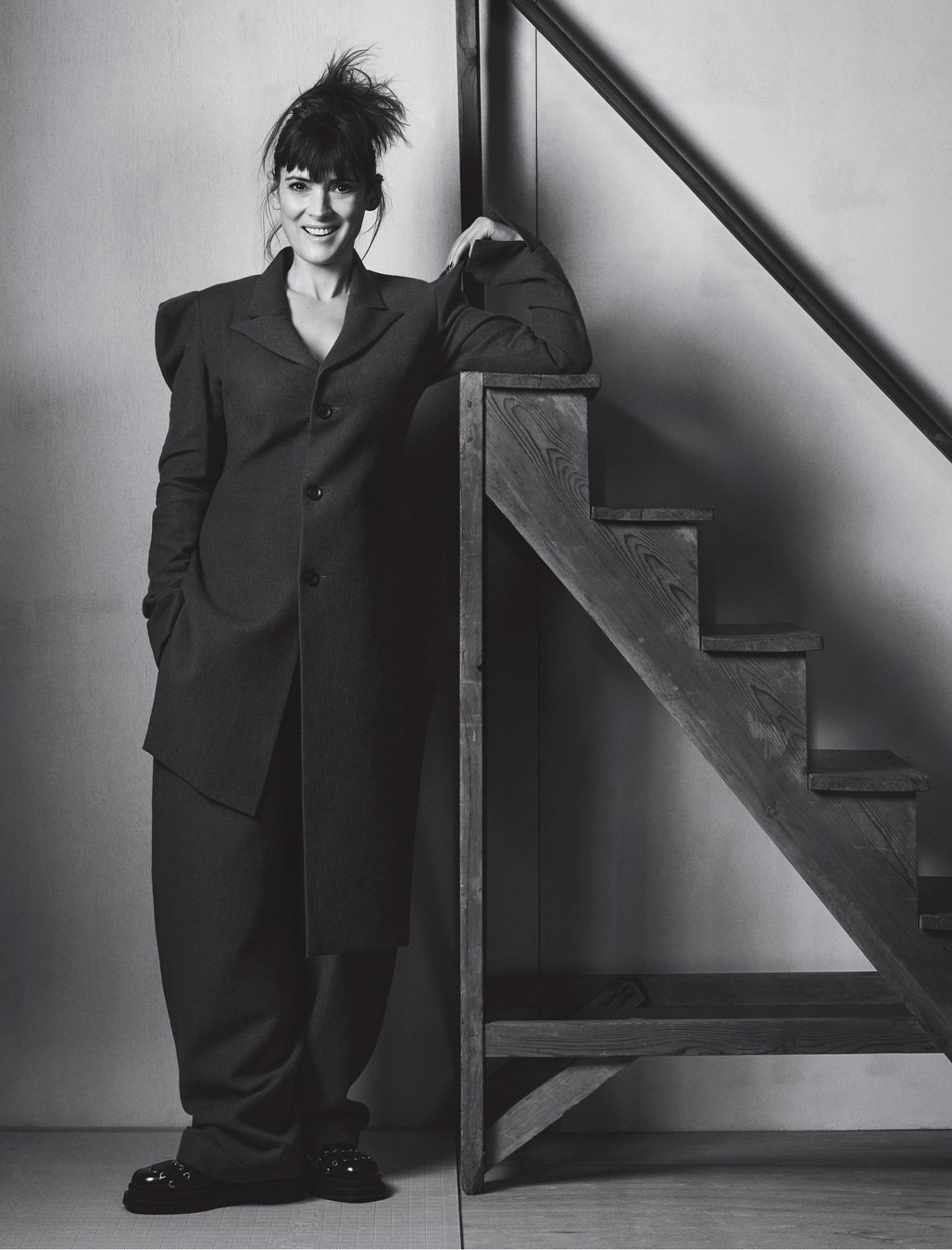

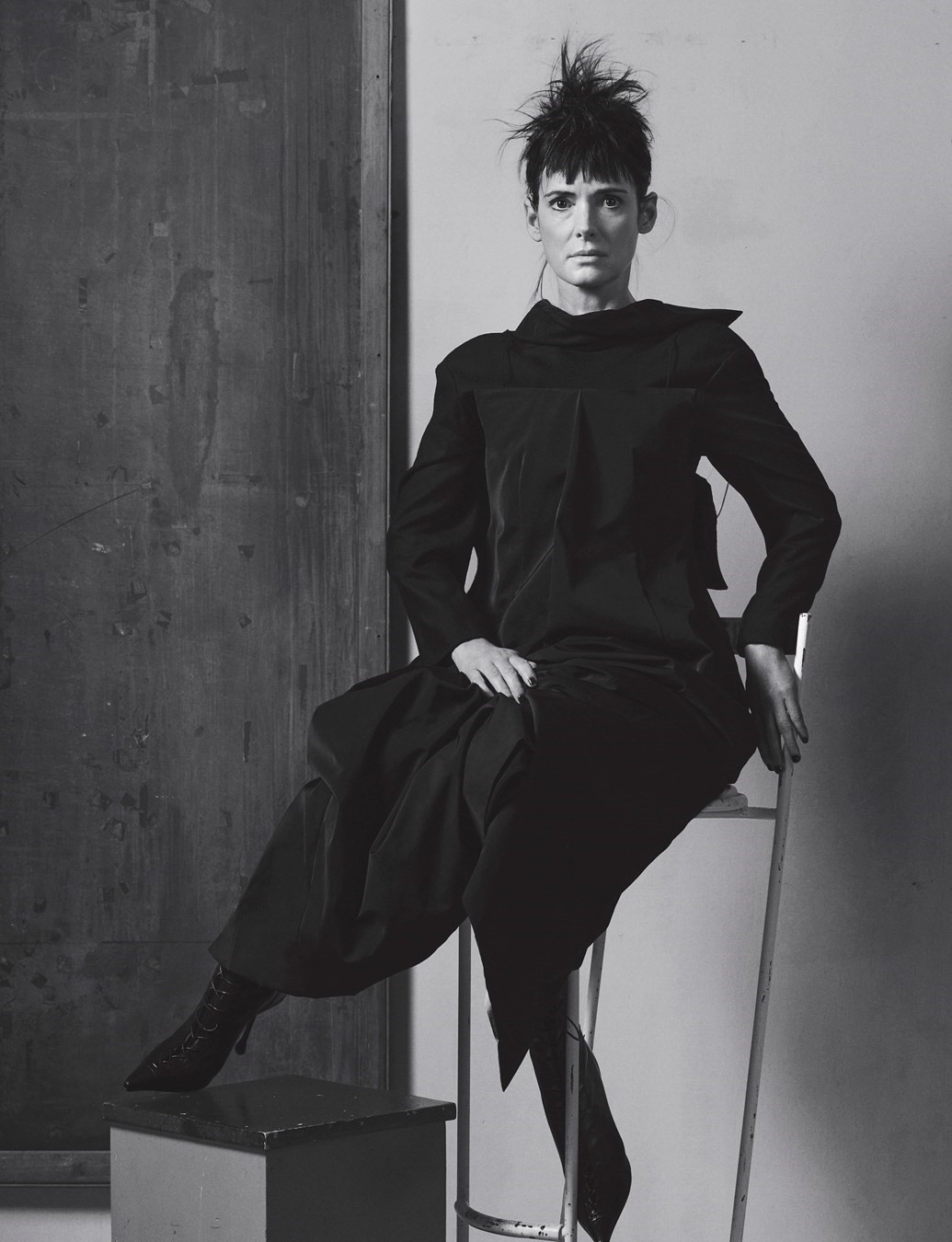

Lead ImageWinona is wearing a jacket in wool crepe by GUCCIPhotography by Craig McDean, Styling by Katie Shillingford

This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine:

In 1987 a strange script about a shadow-eyed goth who prefers the company of ghosts to her parents found its way to Winona Ryder. She was a journal-writing, inky-haired 14-year-old at the time, with a Walkman full of post-punk and a love of film noir. The marble-pale misfit Lydia Deetz in Beetlejuice – a carnivalesque comedy hatched from Tim Burton’s crackpot imagination – could have been written for her.

“I dressed all in black and I had this blue-black, drugstore-dyed hair. I had cut my own bangs so they were really jagged. It’s just wild how similar I looked to her,” Ryder says, Zooming from New York more than three decades later and still dressed in black: T-shirt, dungarees, Leonard Cohen baseball cap. Much like her screen performances, conversations with the singular actor don’t tend to follow well-worn grooves. Today the 52-year-old freewheels from the forthcoming US elections to 70s TV detectives, from Cher to Chernobyl – the latter propelled her to go door to door, drumming up support for the Nuclear Freeze campaign as a kid in northern California. In those days, if the aspiring actor wanted to audition, there was no money for airfare: the family had to climb into a 1969 Volvo without AC and drive seven hours from their book-filled home in Petaluma, north of San Francisco, to the soundstages of LA. “I heard later that I had this reputation for being really choosy, when in actuality we just couldn’t afford to go,” she says. “But Beetlejuice was so unusual – I zoned in on Lydia.” Young actors considered for that role included Brooke Shields, Sarah Jessica Parker, Juliette Lewis and Diane Lane. But that was before Burton met Ryder. “I remember I made my mom wait in the car because I wanted to do it alone,” she says of her first encounter with the unruly-haired auteur. “I was waiting in a side office of this Culver City studio when a young guy came in – I figured he was from the art department. We started talking about old movies and Edward Gorey’s art, and discovered we had this mutual affinity for the actor Peter Lorre. And then I was like, ‘Do you know when Tim Burton is going to show up?’ He said, ‘Oh, that’s me.’ I had no idea directors could be like this cool young person. I said, ‘God I’m sorry, do you want me to read?’ He said, ‘No, I want you to do it.’”

The ghoulish big-hearted caper they went on to make together, about two ghosts who recruit an unhinged demon to exorcise the family occupying their home, was unexpected box-office gold. With its cut-price, calypso-loving spirits, a netherworld like a B-movie sci-fi and a plot best described as stream of consciousness, Beetlejuice brought cult into the mainstream. Amid the likes of Three Men and a Baby and Die Hard, it made the top ten highest-grossing films of 1988, unleashing a Saturday-morning cartoon, Broadway musical, theme park rides and an MS-DOS video game. Ryder had appeared in just two films before Beetlejuice lit the fuse on her career – as the artistic high-schooler that Corey Haim doesn’t fall for in Lucas, and the awkward farmgirl who drives a rusty Chevy into the big city to find her estranged mother in Square Dance. Both were the kind of sensitive outsiders she was a magnet for. But Lydia, with her flying saucer of a hat, creepy doll collection and cobwebby clothes (Ryder wore her Romanian great-grandmother’s mourning lace) pushed that trope to blackly comic extremes. Overnight she became not only the patron saint of Halloween but a lightning rod for misunderstood teens across the nation.

Beetlejuice was an early hint of the actor’s offbeat charisma: eyes that telegraph silent-movie layers of meaning, an instinctual ability to translate our contradictions onto celluloid, and a way of working from the inside out that made it all seem effortless. In the years since, Ryder has evolved into one of our most cherished and idiosyncratic stars. She has played deadpan teen killers and Catholic schoolgirls, gothic brides and gum-chewing cab drivers, android space pirates and vengeful Puritans. She’s matched the likes of her co-stars Daniel Day-Lewis and Gary Oldman in their method-acting brilliance, worked with Scorsese, Coppola, Jarmusch, Aronofsky and Linklater – and repeatedly as the lynchpin of Burton’s dark fairy tales. But the melancholy girl who dreams of plummeting off the Winter River bridge lives on. “Lydia is still the role I get recognised for the most,” she says, “and it’s from children or teens. I find that a little surprising when there’s Middle Earth and CGI — that they would connect to this movie from 1988. I think that must reflect something about Lydia I never realised until I read that Tim really identified with her. There’s a reason Lydia sees the ghosts hanging out in the attic – she’s not distracted with all the stuff that grown-ups get distracted by. There’s something about her that’s pure.”

And yet, despite the film’s diehard fanbase and avalanche of spooky merchandise – stripy dog sweaters, shrunken-head earrings, tombstone backpacks – a sequel never materialised. Beetlejuice Goes Hawaiian, in which the titular 600-year-old corpse enters a surf contest, didn’t make it beyond the page, for better or worse. “Once every couple of years Tim would call me and we’d get together and talk about it, always very top secret,” she says. “So over that time I would sometimes think, how would Lydia have turned out?” This month that question is finally answered in Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, a sequel that sends Lydia back to the jack-o’-lanterned Connecticut town where it all began. Soundtracked by Danny Elfman’s frenzied brass and wonky piano, it’s gratifyingly true to the original’s creaky handmade charm and ghost-train vision, albeit with the budget to scale up the vaudevillian mayhem. There are new additions: Willem Dafoe as an over-caffeinated deceased B-movie actor, Monica Bellucci as the leader of a soul-sucking death cult. And there’s the welcome return of the old: Michael Keaton’s comic genius is undimmed as the mossy-faced miscreant partial to fairground headgear, this time in the throes of a mid-afterlife crisis and messing around with the digital age. But as in 1988, the story’s beating heart is Lydia, now a psychic mediator with her own paranormal TV show, a phoney manager-boyfriend, a problematic sleeping pill habit and an unimpressed school-age daughter of her own (played by Jenna Ortega). “I found so many divine ironies in Lydia identifying with her stepmother now,” Ryder says with a smile. “You can’t shed who Lydia was, but the beauty of it is we all know what happens – life happens.”

Life for Winona Laura Horowitz started a little earlier than planned, at a farmhouse in Winona, Minnesota, where her mother was visiting relatives. She was named after the town, which got its name from a Dakota Sioux legend. The daughter of politically active Haight-Ashbury intellectuals, she grew up in the freethinking, countercultural circles of San Francisco, steeped in Huxley, Kesey and Kerouac. Her parents carved out a scholarly wing of the fringe scene, writing books together and creating the largest library of psychoactive drug literature in the world. Ryder accompanied her Buddhist mother to the hospices where she volunteered, and her dad to Agent Orange and Bow Wow Wow shows (her screen name Ryder was plucked from his Mitch Ryder records). Babysitting came courtesy of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who let her nap in the poetry section of his literary haven, City Lights; her godfather, the psychedelic guru Timothy Leary, took her to Dodgers games. For a few years, the family – Ryder has two half-siblings and a younger brother – joined a collection of like-minded groups on a 300-acre patch among the redwoods of Mendocino, a stripped-back existence without electricity or television. “My mom had been a projectionist in college, and she would get films and screen them on a big sheet in an old barn,” she says. Curled up on pillows during those communal evenings, Ryder soaked up an eclectic range of inspirations: the MGM queen Greer Garson in Random Harvest; the British eccentric Sarah Miles in Ryan’s Daughter; Gena Rowlands in everything. “The films she made with John Cassavetes were revolutionary,” Ryder says. “I vividly remember seeing A Woman Under the Influence and Opening Night, and even though I didn’t understand the grown-up stuff, I felt like I was in the room with these people. Gena is the best there is.”

“You can’t shed who Lydia was, but the beauty of it is we all know what happens – life happens” – Winona Ryder

A decade later, Ryder would spend two weeks driving the nighttime LA freeways with that fearless screen legend. They were fed sandwiches through the car window as they shot Jim Jarmusch’s taxicab anthology, Night on Earth, Ryder as the plucky, straight-talking cabbie, Rowlands her high-powered passenger. But when Ryder was a kid, her love of watching movies hadn’t yet translated into a desire to act in them – instead it fuelled a rich fantasy world. She dug out oversized thrift-store suits in homage to James Cagney or chopped her hair like Sid Vicious. Those dress-ups made her a target when the family moved to more conventional Petaluma when she was 10. “I loved films, but I don’t think I ever saw myself being in films. I was kind of a weird kid,” she says. “I struggled in school. Academically I was doing great, but socially I struggled. When you’re teased and picked on, you just don’t picture yourself doing something like that. But if I was getting pushed around, I would go into this place inside me where it was a movie. I remember once being sent home when something happened and [I was] imagining I was in a film noir. I filtered it, and it helped me not take things so personally.”

Hoping she’d find more empathetic company, Ryder’s parents enrolled her at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco – alumni include Annette Bening, Nicolas Cage and Denzel Washington. She was accepted on the basis of a monologue she adapted from JD Salinger’s novella about a pair of wise oddities, Franny and Zooey. In acting class, the preternatural qualities that drew so much flak at school – her individualism, her imagination, her brain – won her an agent when she was 13. “But I had to keep up my grades,” she says. “I couldn’t work if it coincided with school. My parents – who are just my best friends – were very wary of Hollywood. They associated it with Judy Garland’s tragedy, and we never relocated there. That turned out to be such a gift, because I knew a lot of kids who did bear that. They relocated and were supporting their whole family, and it didn’t turn out so great. I knew a lot of kids who got burnout.”

Ryder’s career snowballed fast, bypassing the traditional child-actor fare of cereal commercials and sitcom high jinks. But even after Beetlejuice she didn’t see herself as marquee material – she preferred the idea of the pithy, off-kilter roles she’d grown up watching. Her touchstone at the time was Ruth Gordon, the septuagenarian actor in Hal Ashby’s 1971 gem about funeral-obsessed oddballs, Harold and Maude. “I was like, they must need actors other than the leads. I loved character actors, and Harold and Maude had a huge impact on me. When I saw that I thought, surely someone must need a young Ruth Gordon?”

Heathers, a Bonnie & Clyde for the Blockbuster and Benetton generation, made her a movie star instead. She was only 16 when she overruled her agent and almost everyone else to play Veronica Sawyer, the nonchalant teen that – with Christian Slater’s JD – embarks on a high-school murder spree between sips of cherry slushie. (Ryder imagined her as a kind of girlhood Humphrey Bogart.) A poison-pen riposte to John Hughes’s syrupy, Brat Pack-filled confections, the 1989 comedy eviscerated taboos – eating disorders, teenage suicide, school shootings, parental neglect – in an acerbic invented slang that has since entered the lexicon. Jennifer Connelly and Heather Graham’s parents wouldn’t even let them audition. But Ryder instantly recognised the film’s vision of school as a Darwinian jungle of rigid hierarchies and casual cruelties, ruled over by a scrunchie-loving clique of mean girls. “I was slipped the script by the guy who wrote Beetlejuice,” Ryder says. “But I had to beg [the director and writer] to let me do it – they didn’t think I was attractive enough to play Veronica. When I was told that, I left the meeting and walked across the street to the Macy’s in the Beverly Center. I had them do a makeover on me and went back in. But it wasn’t until a few actors had turned it down that I got it. I just didn’t have the look that was popular back then. There was a look, and it wasn’t me.”

If Ryder was a mismatch for the Reaganite 80s, a new, less-shiny decade was just around the corner. The climax of Heathers, showing a singed-haired, grubby-faced Veronica lighting her cigarette off the heat of her boyfriend’s suicide vest, exploded any notion that Ryder might be moulded into another Molly Ringwald. She was an altogether different force, a nocturnal-looking antidote for all those not destined to wave pompoms for the cheer team. While Heathers went viral via the grapevine of VHS, Ryder became the focus of equal cult obsession as the renegade you rooted for. “I think I came along at an interesting time,” she says of that moment. “In the 70s there was this revolution in film but then it’s like they found this formula in the mid-80s in American films, whether it was Rambo or John Hughes, where you’re the kid sister or you’re the daughter. There were girls or there were women. That’s a big reason I wanted to make films like Heathers or Little Women – because we didn’t have a lot of that adolescent time, in film or literature. Men did. Men had Lord of the Flies and Holden Caulfield.”

“There were girls or there were women. That’s a big reason I wanted to make films like Heathers or Little Women – because we didn’t have a lot of that adolescent time, in film or literature. Men did” – Winona Ryder

A slew of roles dwelling in that in-betweenness followed: she’s a tangle of contradictory impulses in Mermaids, hugging a Bible one minute and losing her virginity in a belfry the next; a poetry-scribbling smalltown orphan yearning for a bigger life in Welcome Home, Roxy Carmichael; and when she did take that cheerleader role, it was in Burton’s gothic suburban fable Edward Scissorhands opposite her boyfriend at the time, Johnny Depp, as the popular blonde who falls for a freakish, topiary-trimming outcast. “I was like, ‘Tim, I will never forgive you for making me wear a cheerleading outfit and putting me in this wig,’” she says with a laugh. “What did I do to deserve this?”

Post-Edward Scissorhands, Ryder was in a class of her own. Somewhere between lip-syncing to Harry Belafonte and twirling in a flurry of snow as Edward snips her an ice angel, she had entered the bloodstream of a generation. Hollywood’s brainy, funny rebel, she wore vintage to the Oscars, hung out backstage at Replacements shows and stayed up watching cable past 3am. The natural quality she brought to her films she also brought to her interviews, chatting over French fries, or amid the unpacked boxes of her first LA home, or in her pyjamas. She used her pay cheques to buy Salinger first editions and Pier Angeli’s old dresses and was the epitome of the low-maintenance 90s. “There are times when I do like to brush my hair,” she offered when a magazine tried to glean some beauty tips out of her. Being social-media free, she may not have noticed how shots of herself from that era still exert an intangible pull on the fabric of pop culture today, the stuff of obsessive feeds and microscopic dissection: Ryder arriving at a 1991 premiere in a Tom Waits T-shirt and jeans; in a suit jacket on her way to LAX in 1990, her stuff packed in a kids’ suitcase illustrated with dinosaurs; beside Depp the same year at Herb Ritts’s birthday party, in red velvet trousers and DMs. Her early films felt similarly formative for audiences in ways it’s hard to decode – for a moment she was so much a symbol of adolescence that Ryder was in jeopardy of never being permitted to leave it. Few actors make the bumpy transition from child to adult roles, and she was fully aware of the looming deadline. “Oh yeah, it was very drilled into me when I was young that the transition was going to be really hard,” she says. “And so there was always this thing you kind of feared – will you be able to go on to play adult roles or will everyone see you frozen as this kid?”

Two lavish features from a pair of New Hollywood giants provided the catalyst she needed. First came Francis Ford Coppola’s untamed 1992 psychodrama Dracula. It was Ryder who brought the script to Coppola, who transformed it into a baroque extravaganza – all shrieking peacocks and apocalyptic skies – with Gary Oldman as the undead Count. “It was a spec script,” she says. “I met Francis about On the Road because he was thinking of doing that, and at the end of the meeting I gave it to him – a total shot in the dark.” In their resulting film, Ryder morphs from 19th-century schoolmistress to wanton focus of Dracula’s undying desire, drinking the salacious vampire’s blood and eventually slicing off his head. (Coppola sent Oldman a coffin to help him prepare for his role; it has been said that he took to sleeping in it.) “It really wasn’t until Dracula that I felt like I was possibly a lead,” Ryder says. “It definitely took a while, which I think was healthy, because I wasn’t sexualised early.” The film took a mammoth bite out of the box office, won three Academy Awards and if it divided critics at the time, history has reappraised it a ravishing gothic masterstroke.

She stayed in the 19th century for her next, revelatory turn, in Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence. “That was the one,” she nods. “I felt like that was my graduation, in a way. It was one of the greatest roles I’ve ever played.” Set in the piranha pool of Gilded Age Manhattan, the film’s polite smiles conceal lethal intentions and flowers sent or unsent are brutal power plays – Ryder has said that drawing on her experience of 90s Hollywood was not unhelpful. She put icicles into the veins of her seemingly guileless social butterfly, outmanoeuvring all to checkmate the love between her husband (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Michelle Pfeiffer’s bewitching countess. “Marty told me it was his most violent movie – emotionally speaking,” she says. “I will never forget, I was doing a scene where I come home and embrace Daniel. I had taken my hat off and Marty walked up and turned the hatpin around, so it’s pointing at Daniel’s neck. Oh my gosh, I honestly can’t imagine my career without that role.” The delicate shades of her performance brought Ryder an Academy nomination for best supporting actress and she kept the prop paintings from the film’s antique-stuffed drawing rooms as mementoes, hanging them on the walls of her new downtown Manhattan apartment.

By the time Scorsese’s film wrapped in 1992, Ryder had worked back to back for the most formative years of her life. Her entire girlhood had played out onscreen, watched by millions, and it was taking a toll. “There’s a group of us that always keep tabs on each other,” she says of peers who have grown up in a similar glare. “Some of us don’t know each other that well, but if someone needs something, you’re there for them. Because it’s something so few can understand from that perspective.” One of Ryder’s charms is that she never seemed fully at ease with her fame, tugging at it like the neck of an itchy sweater. But in the tabloid decade of the 90s, the media scrutiny was so unrelenting she saw the space between her public and private lives collapse. That year her father gave her Susanna Kaysen’s book Girl, Interrupted, a memoir of the author’s two-year stay in a psychiatric clinic following an overdose. It struck a deeply personal note, and Ryder held onto it. If her name was selling the gossip magazines, it was also wielding box-office power, and she saw the chance to put that clout behind stories that allowed women to be many things at once — to have the messy, contradictory lives usually reserved for men onscreen. “There have been tremendous droughts in this business in terms of complex female roles, throughout my career,” she says. “And I think it’s a real testament to a lot of actresses that they brought layers to their characters or they took chances, or came up with their own backstory, because there were long periods where we didn’t have that much to work with.”

Ryder channelled her energy into fixing that: she jump-started 1994’s Little Women, insisting on a female director and supporting the casting of Kirsten Dunst and Clare Danes as her younger sisters (not to mention putting out Danes’s wig when it caught fire on a bedtime candle). Ryder’s fiery performance as the wilful Jo March sent her back to the Oscars, this time with a nomination for best actress. The same year, her name got Ben Stiller’s directing debut, Reality Bites, greenlit and she championed Ethan Hawke to co-star in the Gen X classic about twentysomethings figuring out their frayed Boomer inheritance while holding down jobs at Gap.

She was back in period costume once more, on a mosquito-ridden island off the coast of New England, for the playwright Arthur Miller’s own adaptation of The Crucible, set during the Salem witch trials. Opposite Day-Lewis again, she’s raw and unbridled as Abigail Williams, her features dissolving and reforming as she see-saws between avenging Valkyrie and calculating manipulator, giddily watching necks snap on the scaffold. And then, six years after reading Kaysen’s book, Ryder travelled to a bleak, red-brick mental health hospital in Pennsylvania to star in her long-gestating labour of love, Girl, Interrupted. As executive producer, it was Ryder who tapped Angelina Jolie to co-star – and she could have chosen Jolie’s sociopathic firework of a part. But her heart lay with the deep waters and amorphous ache of the film’s wounded protagonist. Between them they pulled off an artful, subversive treasure, reminiscent of the New Hollywood cinema Ryder grew up on, this time thrillingly with women as the rebellious, flawed outsiders – a One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest for 1999. Her star was etched into the Walk of Fame the next year.

It has been well recorded things got a little muddy after that, when the chasm between public fame and private pain crystallised with Ryder’s arrest for shoplifting in 2001. That moment is remarkable less for the transgression itself – pretty slight by Hollywood standards – but for the vilification that ensued. Many of her male colleagues have bounced swiftly back from far worse. It’s been said that the truly unforgivable fact might have been that, aged 30, she had hit a bracket that didn’t gel with the ingenue conception of her. What’s clear is that after 15 years onscreen, Ryder was overdue a break. “The one good thing to come out of everything that happened is that I wasn’t happy where I was,” she told AnOther Magazine back in 2006, the first time she was on our cover. “I wasn’t happy being so famous and being written about all the time. Hollywood people associate movies solely with fame and I didn’t enjoy working in that way any more.”

And so, after a couple of years’ respite in northern California, Ryder set about taking the kind of chewy character parts that originally lured her onto the screen in the first place. She joined up with her longtime friend Keanu Reeves for Richard Linklater’s rotoscoped take on Philip K Dick’s mind-scrambling novel A Scanner Darkly, playing a jittery addict caught in a web of shady government forces. She infused the perfect recipe of pathos and humour into her overdramatic adulterous poet in Rebecca Miller’s The Private Lives of Pippa Lee. And she was electrifying as a washed-up prima ballerina usurped by fresh feet in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan, dark impulses shooting from her mascara-smudged eyes – Ryder kept Bette Davis in All About Eve at the back of her mind for that one. She snipped her eyelashes to play a bruised Yonkers councilwoman in the HBO series Show Me a Hero, after its writer David Simon warned her he didn’t want “Winona eyes” for a character whose gestures of affection constitute a shot of sambuca and a light punch in the arm. Some roles harnessed the connective tissue of Ryder’s own trajectory — the weight of an icon’s fame, the notion of a fall from grace, the nostalgic pangs evoked by a certain era. All confirmed that Ryder is transfixing in a way it’s hard to do the maths on, raising the temperature of a scene with her presence.

That’s something the Duffer Brothers were relying on in 2016, when they made her the North Star of their 80s-set Netflix show Stranger Things. Circling a crew of Indiana kids who battle goo-dripping monsters, Cold War conspiracies and smalltown suburban prejudices, the show’s nostalgic mash-up of Stephen King and Steven Spielberg became phenomenally successful. Ryder felt the echoes of her childhood as keenly as its devoted fans, who revel in the speed-pedalled BMXs, Dungeons & Dragons camaraderie and vintage analogue synth. “I have to tell you, on the first season, one of the hardest reckonings for me was the day the kids held up a record and said, ‘What is this?’ I honestly started welling up with tears. I was like, ‘That’s how we listened to music!’ And there’s nothing like that sound of the needle hitting the vinyl! I’m officially old school because that is still how I listen to music. I miss those tangible things.”

From its debut season, when her character, Joyce Byers, communicates with her abducted son via a flashing knot of Christmas lights, Ryder turned what might have been a neurotic cut-out into a chain-smoking eccentric with a black sense of humour and unguessed-at strengths. The director twins have admitted Joyce wasn’t much more than a devoted mother on the page. But Ryder knows how to spin gold at such moments. “I really fought for her flaws,” she says. “I didn’t want her to be a supermom. I wanted it to reflect the economics of being broke and having to work two jobs and probably having to lean very unhealthily on your older kid.” She says she thought about Mike Nichols’s 1983 drama, Silkwood, based on the life and mysterious death of the nuclear-plant whistleblower Karen Silkwood. “I had a ‘Who Killed Karen Silkwood?’ T-shirt growing up,” she says. “I was so incredibly moved by characters like that, who are just doing the best they can and it’s not enough. Karen is working at this plant, living with her gay best friend, played by Cher, and she’s not doing it for glory or money, she’s trying to do the right thing. I think maybe because Stranger Things was a genre show, I wanted to make Joyce as human as possible. And the only way to really do that is to show we’re contradictory beings.”

When we speak, Ryder is six months into the yearlong production of the fifth and final season – her last foray into the Upside Down. She and her partner of more than 13 years, the designer Scott Mackinlay Hahn, split their time between New York and LA, but Atlanta, where Stranger Things is shot, has increasingly become a third home. “I never thought it was going to be a ten-year thing,” she says. “I mean the kids are in their early twenties now and they were 11 or 12 when it started.” Few actors could better understand the disorientating rollercoaster her young co-stars have ridden in that time. Ryder feels as protective of them as she is onscreen. “With TV you’re in someone’s house as opposed to their movie theatre. They feel like they know you, that you’re theirs,” she says. “I get it, because I love detective shows – DCI Jane Tennison? You get to feel very close to these people. But it’s especially tricky if it’s growing kids. They should be off limits.”

“I always felt lucky that I was considered kind of a weirdo for enough time … I was still around really inappropriate behaviour. But I felt like my identity protected me in a way” – Winona Ryder

Working with children the same age she was during her early years navigating 80s Hollywood has emphasised for her how unregulated it was. “I never had an HR meeting until #MeToo! It’s ultimately very good, but I was in my late forties by then,” she says. “I used to feel very guilty that because of my parents’ choices and keeping me home, I wasn’t out there pounding the pavement. My heart breaks for the kids who weren’t protected. When I was doing Heathers, I stayed with these young actresses in their twenties that my parents knew and trusted, and I would go with them to their auditions for commercials sometimes. I’d be in the waiting room and see through the open door that they were told to take their clothes off – not completely – but really humiliating stuff that was not OK at all. The lines were so blurry. With everything that’s happened in the past six years, it takes remembering something and thinking about it happening to someone of the same age you were, like Jenna [Ortega] or Sadie [Sink], and it’s like, ‘Five-alarm fire, not OK!’ Because everything back then was always, ‘You’re so sensitive, he’s just kidding. Get a sense of humour.’ I always felt lucky that I was considered kind of a weirdo for enough time … I was still around really inappropriate behaviour. But I felt like my identity protected me in a way.”

Ryder recently found her old Filofax from those child-actor days: “Remember when your whole life was your Filofax? I’ve written, ‘If Lost, Will Reward’ and there’s a stamp of the studio and my old phone number. The front page is a Polaroid from the Beetlejuice set – it’s me and Tim at the Day-o dinner scene,” she says. “I had no idea at the time what Beetlejuice was going to be. But I remember when we wrapped feeling really blue and thinking, how am I ever going to top this?” That life-altering shoot, and the widespread adoration for the film that followed, made stepping back into Lydia’s lace-up boots a little daunting. “I had built up a lot of nerves, because this film is very beloved,” she says. In the end, though, it was like time-travelling back to the moment she and Burton recognised each other as kindred outsiders in that Culver City studio in 1987. “Tim was right there by the camera, almost mirroring me, which is how we made it the first time, and how I grew up – there were no monitors or Video Village back then. I knew he would never do anything to compromise his vision. I’d been thinking, OK, Lydia is popping pills, she’s very lost, she’s on autopilot … But then Tim said something very simple. He said, ‘Let’s try one where you’re really sincere.’ And suddenly I remembered that was his direction to me on the first Beetlejuice – that Lydia might look weird but she’s actually really sincere. Every time I’ve worked with Tim, he would say there might be chaos around me, but what I’m playing is something very real. It blew me away how much it brought back those initial feelings.”

If Burton’s ingenious new spectacle reaffirms his status as a true cinematic one-off, the same can be said of his friend and muse, the self-described weird kid who brought her edge to Hollywood. Never the polished career strategist, today Ryder is the guardian angel of an award-winning show, the star of the year’s most anticipated blockbuster and, 36 years after her breakthrough as the peculiar girl who eats Chinese takeout in a mourning veil, still the nonconformist we root for, offscreen and on.

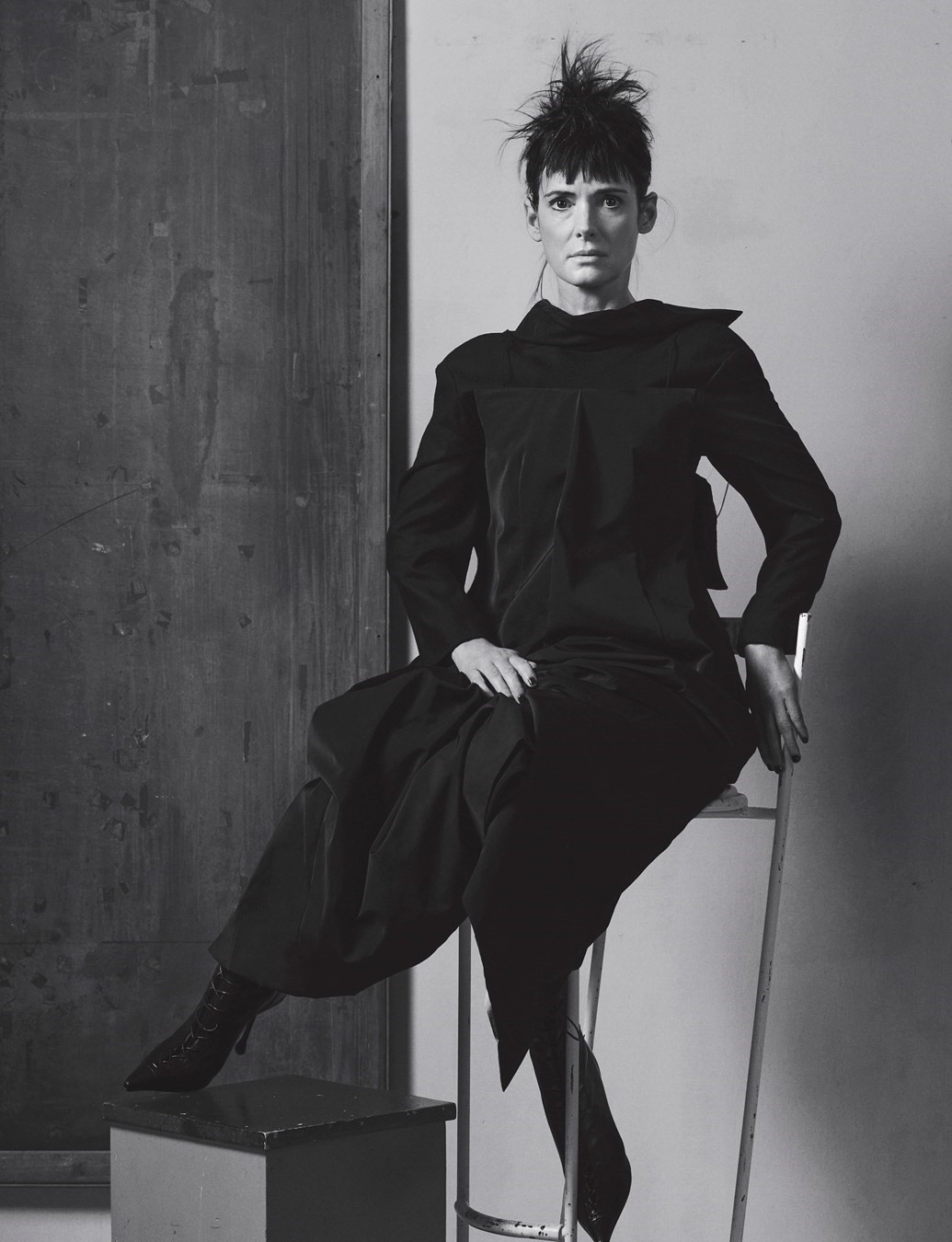

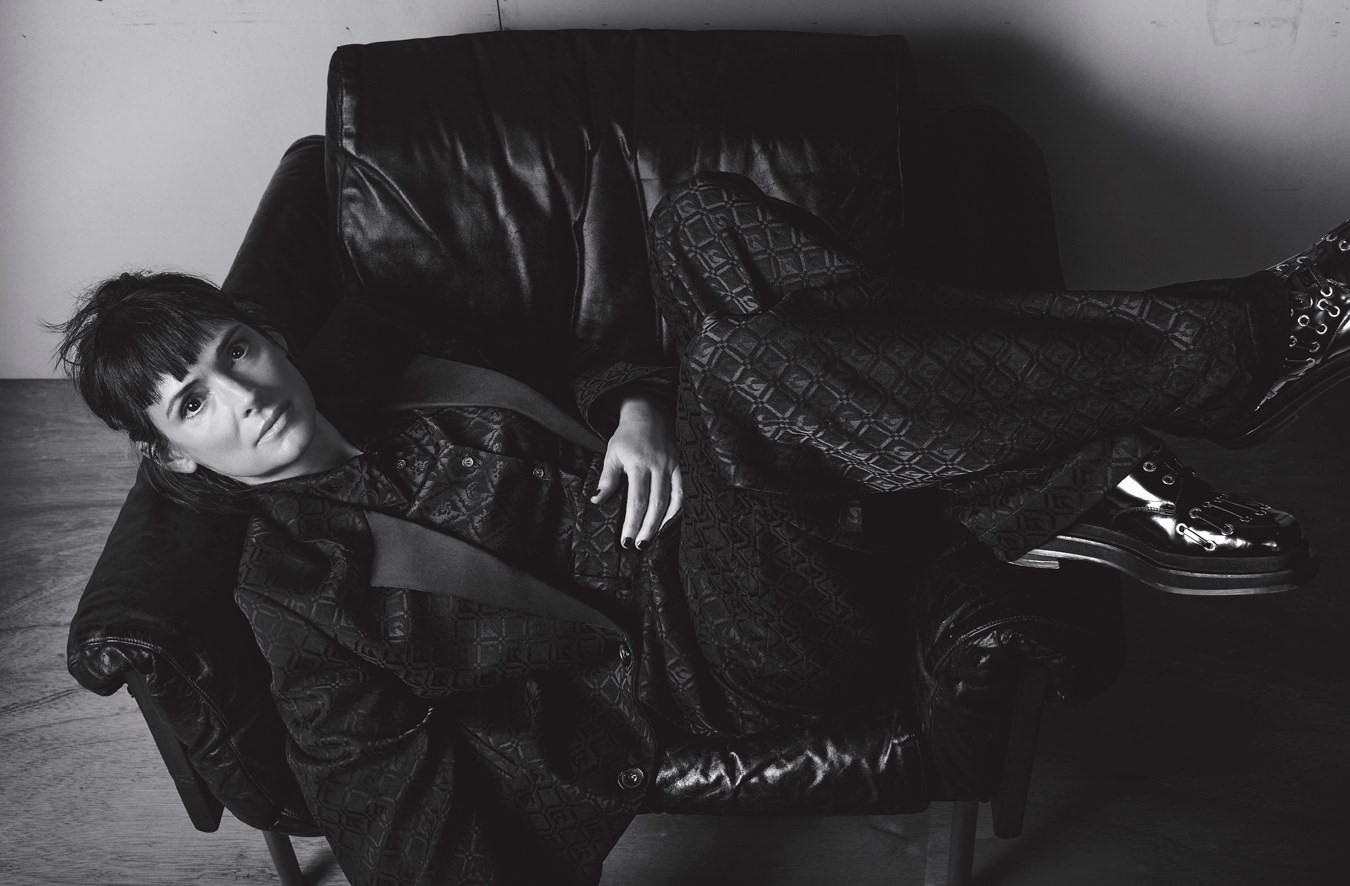

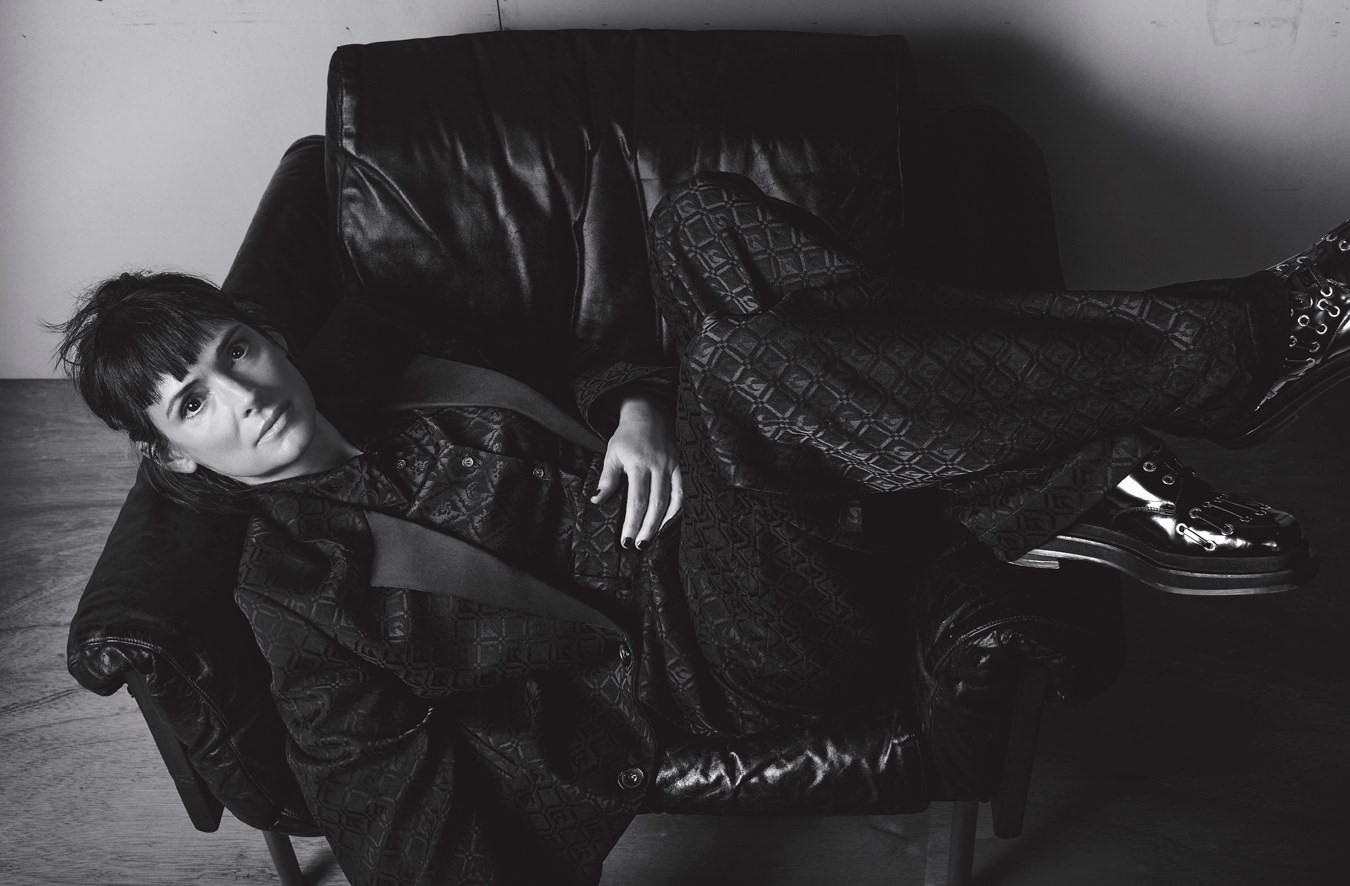

Hair: Jimmy Paul at Susan Price. Make-up: Francelle Daly at 2b Management using LOVE+CRAFT+BEAUTY. Manicure: Megumi Yamamoto at Susan Price using UKA. Set design: Stefan Beckman at Exposure NY. Digital tech: Tadaaki Shibuya. Photographic assistants: Shri Parameshwaran, Nick Krasznai and Tony Jarum. Styling assistant: Precious Greham. Seamstress: Hailey Desjardins. Hair assistant: Tiffany Beach. Make-up assistant: Madrona Redhawk. Set-design assistants: Syvash Jefferson and Zac Pepere. Production: Gracey Connelly. Retouching: Gloss Studio. Special thanks to Smashbox Studios

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 12 September 2024. Pre-order here.

in HTML format, including tags, to make it appealing and easy to read for Japanese-speaking readers aged 20 to 40 interested in fashion. Organize the content with appropriate headings and subheadings (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6), translating all text, including headings, into Japanese. Retain any existing

tags from

Lead ImageWinona is wearing a jacket in wool crepe by GUCCIPhotography by Craig McDean, Styling by Katie Shillingford

This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine:

In 1987 a strange script about a shadow-eyed goth who prefers the company of ghosts to her parents found its way to Winona Ryder. She was a journal-writing, inky-haired 14-year-old at the time, with a Walkman full of post-punk and a love of film noir. The marble-pale misfit Lydia Deetz in Beetlejuice – a carnivalesque comedy hatched from Tim Burton’s crackpot imagination – could have been written for her.

“I dressed all in black and I had this blue-black, drugstore-dyed hair. I had cut my own bangs so they were really jagged. It’s just wild how similar I looked to her,” Ryder says, Zooming from New York more than three decades later and still dressed in black: T-shirt, dungarees, Leonard Cohen baseball cap. Much like her screen performances, conversations with the singular actor don’t tend to follow well-worn grooves. Today the 52-year-old freewheels from the forthcoming US elections to 70s TV detectives, from Cher to Chernobyl – the latter propelled her to go door to door, drumming up support for the Nuclear Freeze campaign as a kid in northern California. In those days, if the aspiring actor wanted to audition, there was no money for airfare: the family had to climb into a 1969 Volvo without AC and drive seven hours from their book-filled home in Petaluma, north of San Francisco, to the soundstages of LA. “I heard later that I had this reputation for being really choosy, when in actuality we just couldn’t afford to go,” she says. “But Beetlejuice was so unusual – I zoned in on Lydia.” Young actors considered for that role included Brooke Shields, Sarah Jessica Parker, Juliette Lewis and Diane Lane. But that was before Burton met Ryder. “I remember I made my mom wait in the car because I wanted to do it alone,” she says of her first encounter with the unruly-haired auteur. “I was waiting in a side office of this Culver City studio when a young guy came in – I figured he was from the art department. We started talking about old movies and Edward Gorey’s art, and discovered we had this mutual affinity for the actor Peter Lorre. And then I was like, ‘Do you know when Tim Burton is going to show up?’ He said, ‘Oh, that’s me.’ I had no idea directors could be like this cool young person. I said, ‘God I’m sorry, do you want me to read?’ He said, ‘No, I want you to do it.’”

The ghoulish big-hearted caper they went on to make together, about two ghosts who recruit an unhinged demon to exorcise the family occupying their home, was unexpected box-office gold. With its cut-price, calypso-loving spirits, a netherworld like a B-movie sci-fi and a plot best described as stream of consciousness, Beetlejuice brought cult into the mainstream. Amid the likes of Three Men and a Baby and Die Hard, it made the top ten highest-grossing films of 1988, unleashing a Saturday-morning cartoon, Broadway musical, theme park rides and an MS-DOS video game. Ryder had appeared in just two films before Beetlejuice lit the fuse on her career – as the artistic high-schooler that Corey Haim doesn’t fall for in Lucas, and the awkward farmgirl who drives a rusty Chevy into the big city to find her estranged mother in Square Dance. Both were the kind of sensitive outsiders she was a magnet for. But Lydia, with her flying saucer of a hat, creepy doll collection and cobwebby clothes (Ryder wore her Romanian great-grandmother’s mourning lace) pushed that trope to blackly comic extremes. Overnight she became not only the patron saint of Halloween but a lightning rod for misunderstood teens across the nation.

Beetlejuice was an early hint of the actor’s offbeat charisma: eyes that telegraph silent-movie layers of meaning, an instinctual ability to translate our contradictions onto celluloid, and a way of working from the inside out that made it all seem effortless. In the years since, Ryder has evolved into one of our most cherished and idiosyncratic stars. She has played deadpan teen killers and Catholic schoolgirls, gothic brides and gum-chewing cab drivers, android space pirates and vengeful Puritans. She’s matched the likes of her co-stars Daniel Day-Lewis and Gary Oldman in their method-acting brilliance, worked with Scorsese, Coppola, Jarmusch, Aronofsky and Linklater – and repeatedly as the lynchpin of Burton’s dark fairy tales. But the melancholy girl who dreams of plummeting off the Winter River bridge lives on. “Lydia is still the role I get recognised for the most,” she says, “and it’s from children or teens. I find that a little surprising when there’s Middle Earth and CGI — that they would connect to this movie from 1988. I think that must reflect something about Lydia I never realised until I read that Tim really identified with her. There’s a reason Lydia sees the ghosts hanging out in the attic – she’s not distracted with all the stuff that grown-ups get distracted by. There’s something about her that’s pure.”

And yet, despite the film’s diehard fanbase and avalanche of spooky merchandise – stripy dog sweaters, shrunken-head earrings, tombstone backpacks – a sequel never materialised. Beetlejuice Goes Hawaiian, in which the titular 600-year-old corpse enters a surf contest, didn’t make it beyond the page, for better or worse. “Once every couple of years Tim would call me and we’d get together and talk about it, always very top secret,” she says. “So over that time I would sometimes think, how would Lydia have turned out?” This month that question is finally answered in Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, a sequel that sends Lydia back to the jack-o’-lanterned Connecticut town where it all began. Soundtracked by Danny Elfman’s frenzied brass and wonky piano, it’s gratifyingly true to the original’s creaky handmade charm and ghost-train vision, albeit with the budget to scale up the vaudevillian mayhem. There are new additions: Willem Dafoe as an over-caffeinated deceased B-movie actor, Monica Bellucci as the leader of a soul-sucking death cult. And there’s the welcome return of the old: Michael Keaton’s comic genius is undimmed as the mossy-faced miscreant partial to fairground headgear, this time in the throes of a mid-afterlife crisis and messing around with the digital age. But as in 1988, the story’s beating heart is Lydia, now a psychic mediator with her own paranormal TV show, a phoney manager-boyfriend, a problematic sleeping pill habit and an unimpressed school-age daughter of her own (played by Jenna Ortega). “I found so many divine ironies in Lydia identifying with her stepmother now,” Ryder says with a smile. “You can’t shed who Lydia was, but the beauty of it is we all know what happens – life happens.”

Life for Winona Laura Horowitz started a little earlier than planned, at a farmhouse in Winona, Minnesota, where her mother was visiting relatives. She was named after the town, which got its name from a Dakota Sioux legend. The daughter of politically active Haight-Ashbury intellectuals, she grew up in the freethinking, countercultural circles of San Francisco, steeped in Huxley, Kesey and Kerouac. Her parents carved out a scholarly wing of the fringe scene, writing books together and creating the largest library of psychoactive drug literature in the world. Ryder accompanied her Buddhist mother to the hospices where she volunteered, and her dad to Agent Orange and Bow Wow Wow shows (her screen name Ryder was plucked from his Mitch Ryder records). Babysitting came courtesy of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who let her nap in the poetry section of his literary haven, City Lights; her godfather, the psychedelic guru Timothy Leary, took her to Dodgers games. For a few years, the family – Ryder has two half-siblings and a younger brother – joined a collection of like-minded groups on a 300-acre patch among the redwoods of Mendocino, a stripped-back existence without electricity or television. “My mom had been a projectionist in college, and she would get films and screen them on a big sheet in an old barn,” she says. Curled up on pillows during those communal evenings, Ryder soaked up an eclectic range of inspirations: the MGM queen Greer Garson in Random Harvest; the British eccentric Sarah Miles in Ryan’s Daughter; Gena Rowlands in everything. “The films she made with John Cassavetes were revolutionary,” Ryder says. “I vividly remember seeing A Woman Under the Influence and Opening Night, and even though I didn’t understand the grown-up stuff, I felt like I was in the room with these people. Gena is the best there is.”

“You can’t shed who Lydia was, but the beauty of it is we all know what happens – life happens” – Winona Ryder

A decade later, Ryder would spend two weeks driving the nighttime LA freeways with that fearless screen legend. They were fed sandwiches through the car window as they shot Jim Jarmusch’s taxicab anthology, Night on Earth, Ryder as the plucky, straight-talking cabbie, Rowlands her high-powered passenger. But when Ryder was a kid, her love of watching movies hadn’t yet translated into a desire to act in them – instead it fuelled a rich fantasy world. She dug out oversized thrift-store suits in homage to James Cagney or chopped her hair like Sid Vicious. Those dress-ups made her a target when the family moved to more conventional Petaluma when she was 10. “I loved films, but I don’t think I ever saw myself being in films. I was kind of a weird kid,” she says. “I struggled in school. Academically I was doing great, but socially I struggled. When you’re teased and picked on, you just don’t picture yourself doing something like that. But if I was getting pushed around, I would go into this place inside me where it was a movie. I remember once being sent home when something happened and [I was] imagining I was in a film noir. I filtered it, and it helped me not take things so personally.”

Hoping she’d find more empathetic company, Ryder’s parents enrolled her at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco – alumni include Annette Bening, Nicolas Cage and Denzel Washington. She was accepted on the basis of a monologue she adapted from JD Salinger’s novella about a pair of wise oddities, Franny and Zooey. In acting class, the preternatural qualities that drew so much flak at school – her individualism, her imagination, her brain – won her an agent when she was 13. “But I had to keep up my grades,” she says. “I couldn’t work if it coincided with school. My parents – who are just my best friends – were very wary of Hollywood. They associated it with Judy Garland’s tragedy, and we never relocated there. That turned out to be such a gift, because I knew a lot of kids who did bear that. They relocated and were supporting their whole family, and it didn’t turn out so great. I knew a lot of kids who got burnout.”

Ryder’s career snowballed fast, bypassing the traditional child-actor fare of cereal commercials and sitcom high jinks. But even after Beetlejuice she didn’t see herself as marquee material – she preferred the idea of the pithy, off-kilter roles she’d grown up watching. Her touchstone at the time was Ruth Gordon, the septuagenarian actor in Hal Ashby’s 1971 gem about funeral-obsessed oddballs, Harold and Maude. “I was like, they must need actors other than the leads. I loved character actors, and Harold and Maude had a huge impact on me. When I saw that I thought, surely someone must need a young Ruth Gordon?”

Heathers, a Bonnie & Clyde for the Blockbuster and Benetton generation, made her a movie star instead. She was only 16 when she overruled her agent and almost everyone else to play Veronica Sawyer, the nonchalant teen that – with Christian Slater’s JD – embarks on a high-school murder spree between sips of cherry slushie. (Ryder imagined her as a kind of girlhood Humphrey Bogart.) A poison-pen riposte to John Hughes’s syrupy, Brat Pack-filled confections, the 1989 comedy eviscerated taboos – eating disorders, teenage suicide, school shootings, parental neglect – in an acerbic invented slang that has since entered the lexicon. Jennifer Connelly and Heather Graham’s parents wouldn’t even let them audition. But Ryder instantly recognised the film’s vision of school as a Darwinian jungle of rigid hierarchies and casual cruelties, ruled over by a scrunchie-loving clique of mean girls. “I was slipped the script by the guy who wrote Beetlejuice,” Ryder says. “But I had to beg [the director and writer] to let me do it – they didn’t think I was attractive enough to play Veronica. When I was told that, I left the meeting and walked across the street to the Macy’s in the Beverly Center. I had them do a makeover on me and went back in. But it wasn’t until a few actors had turned it down that I got it. I just didn’t have the look that was popular back then. There was a look, and it wasn’t me.”

If Ryder was a mismatch for the Reaganite 80s, a new, less-shiny decade was just around the corner. The climax of Heathers, showing a singed-haired, grubby-faced Veronica lighting her cigarette off the heat of her boyfriend’s suicide vest, exploded any notion that Ryder might be moulded into another Molly Ringwald. She was an altogether different force, a nocturnal-looking antidote for all those not destined to wave pompoms for the cheer team. While Heathers went viral via the grapevine of VHS, Ryder became the focus of equal cult obsession as the renegade you rooted for. “I think I came along at an interesting time,” she says of that moment. “In the 70s there was this revolution in film but then it’s like they found this formula in the mid-80s in American films, whether it was Rambo or John Hughes, where you’re the kid sister or you’re the daughter. There were girls or there were women. That’s a big reason I wanted to make films like Heathers or Little Women – because we didn’t have a lot of that adolescent time, in film or literature. Men did. Men had Lord of the Flies and Holden Caulfield.”

“There were girls or there were women. That’s a big reason I wanted to make films like Heathers or Little Women – because we didn’t have a lot of that adolescent time, in film or literature. Men did” – Winona Ryder

A slew of roles dwelling in that in-betweenness followed: she’s a tangle of contradictory impulses in Mermaids, hugging a Bible one minute and losing her virginity in a belfry the next; a poetry-scribbling smalltown orphan yearning for a bigger life in Welcome Home, Roxy Carmichael; and when she did take that cheerleader role, it was in Burton’s gothic suburban fable Edward Scissorhands opposite her boyfriend at the time, Johnny Depp, as the popular blonde who falls for a freakish, topiary-trimming outcast. “I was like, ‘Tim, I will never forgive you for making me wear a cheerleading outfit and putting me in this wig,’” she says with a laugh. “What did I do to deserve this?”

Post-Edward Scissorhands, Ryder was in a class of her own. Somewhere between lip-syncing to Harry Belafonte and twirling in a flurry of snow as Edward snips her an ice angel, she had entered the bloodstream of a generation. Hollywood’s brainy, funny rebel, she wore vintage to the Oscars, hung out backstage at Replacements shows and stayed up watching cable past 3am. The natural quality she brought to her films she also brought to her interviews, chatting over French fries, or amid the unpacked boxes of her first LA home, or in her pyjamas. She used her pay cheques to buy Salinger first editions and Pier Angeli’s old dresses and was the epitome of the low-maintenance 90s. “There are times when I do like to brush my hair,” she offered when a magazine tried to glean some beauty tips out of her. Being social-media free, she may not have noticed how shots of herself from that era still exert an intangible pull on the fabric of pop culture today, the stuff of obsessive feeds and microscopic dissection: Ryder arriving at a 1991 premiere in a Tom Waits T-shirt and jeans; in a suit jacket on her way to LAX in 1990, her stuff packed in a kids’ suitcase illustrated with dinosaurs; beside Depp the same year at Herb Ritts’s birthday party, in red velvet trousers and DMs. Her early films felt similarly formative for audiences in ways it’s hard to decode – for a moment she was so much a symbol of adolescence that Ryder was in jeopardy of never being permitted to leave it. Few actors make the bumpy transition from child to adult roles, and she was fully aware of the looming deadline. “Oh yeah, it was very drilled into me when I was young that the transition was going to be really hard,” she says. “And so there was always this thing you kind of feared – will you be able to go on to play adult roles or will everyone see you frozen as this kid?”

Two lavish features from a pair of New Hollywood giants provided the catalyst she needed. First came Francis Ford Coppola’s untamed 1992 psychodrama Dracula. It was Ryder who brought the script to Coppola, who transformed it into a baroque extravaganza – all shrieking peacocks and apocalyptic skies – with Gary Oldman as the undead Count. “It was a spec script,” she says. “I met Francis about On the Road because he was thinking of doing that, and at the end of the meeting I gave it to him – a total shot in the dark.” In their resulting film, Ryder morphs from 19th-century schoolmistress to wanton focus of Dracula’s undying desire, drinking the salacious vampire’s blood and eventually slicing off his head. (Coppola sent Oldman a coffin to help him prepare for his role; it has been said that he took to sleeping in it.) “It really wasn’t until Dracula that I felt like I was possibly a lead,” Ryder says. “It definitely took a while, which I think was healthy, because I wasn’t sexualised early.” The film took a mammoth bite out of the box office, won three Academy Awards and if it divided critics at the time, history has reappraised it a ravishing gothic masterstroke.

She stayed in the 19th century for her next, revelatory turn, in Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence. “That was the one,” she nods. “I felt like that was my graduation, in a way. It was one of the greatest roles I’ve ever played.” Set in the piranha pool of Gilded Age Manhattan, the film’s polite smiles conceal lethal intentions and flowers sent or unsent are brutal power plays – Ryder has said that drawing on her experience of 90s Hollywood was not unhelpful. She put icicles into the veins of her seemingly guileless social butterfly, outmanoeuvring all to checkmate the love between her husband (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Michelle Pfeiffer’s bewitching countess. “Marty told me it was his most violent movie – emotionally speaking,” she says. “I will never forget, I was doing a scene where I come home and embrace Daniel. I had taken my hat off and Marty walked up and turned the hatpin around, so it’s pointing at Daniel’s neck. Oh my gosh, I honestly can’t imagine my career without that role.” The delicate shades of her performance brought Ryder an Academy nomination for best supporting actress and she kept the prop paintings from the film’s antique-stuffed drawing rooms as mementoes, hanging them on the walls of her new downtown Manhattan apartment.

By the time Scorsese’s film wrapped in 1992, Ryder had worked back to back for the most formative years of her life. Her entire girlhood had played out onscreen, watched by millions, and it was taking a toll. “There’s a group of us that always keep tabs on each other,” she says of peers who have grown up in a similar glare. “Some of us don’t know each other that well, but if someone needs something, you’re there for them. Because it’s something so few can understand from that perspective.” One of Ryder’s charms is that she never seemed fully at ease with her fame, tugging at it like the neck of an itchy sweater. But in the tabloid decade of the 90s, the media scrutiny was so unrelenting she saw the space between her public and private lives collapse. That year her father gave her Susanna Kaysen’s book Girl, Interrupted, a memoir of the author’s two-year stay in a psychiatric clinic following an overdose. It struck a deeply personal note, and Ryder held onto it. If her name was selling the gossip magazines, it was also wielding box-office power, and she saw the chance to put that clout behind stories that allowed women to be many things at once — to have the messy, contradictory lives usually reserved for men onscreen. “There have been tremendous droughts in this business in terms of complex female roles, throughout my career,” she says. “And I think it’s a real testament to a lot of actresses that they brought layers to their characters or they took chances, or came up with their own backstory, because there were long periods where we didn’t have that much to work with.”

Ryder channelled her energy into fixing that: she jump-started 1994’s Little Women, insisting on a female director and supporting the casting of Kirsten Dunst and Clare Danes as her younger sisters (not to mention putting out Danes’s wig when it caught fire on a bedtime candle). Ryder’s fiery performance as the wilful Jo March sent her back to the Oscars, this time with a nomination for best actress. The same year, her name got Ben Stiller’s directing debut, Reality Bites, greenlit and she championed Ethan Hawke to co-star in the Gen X classic about twentysomethings figuring out their frayed Boomer inheritance while holding down jobs at Gap.

She was back in period costume once more, on a mosquito-ridden island off the coast of New England, for the playwright Arthur Miller’s own adaptation of The Crucible, set during the Salem witch trials. Opposite Day-Lewis again, she’s raw and unbridled as Abigail Williams, her features dissolving and reforming as she see-saws between avenging Valkyrie and calculating manipulator, giddily watching necks snap on the scaffold. And then, six years after reading Kaysen’s book, Ryder travelled to a bleak, red-brick mental health hospital in Pennsylvania to star in her long-gestating labour of love, Girl, Interrupted. As executive producer, it was Ryder who tapped Angelina Jolie to co-star – and she could have chosen Jolie’s sociopathic firework of a part. But her heart lay with the deep waters and amorphous ache of the film’s wounded protagonist. Between them they pulled off an artful, subversive treasure, reminiscent of the New Hollywood cinema Ryder grew up on, this time thrillingly with women as the rebellious, flawed outsiders – a One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest for 1999. Her star was etched into the Walk of Fame the next year.

It has been well recorded things got a little muddy after that, when the chasm between public fame and private pain crystallised with Ryder’s arrest for shoplifting in 2001. That moment is remarkable less for the transgression itself – pretty slight by Hollywood standards – but for the vilification that ensued. Many of her male colleagues have bounced swiftly back from far worse. It’s been said that the truly unforgivable fact might have been that, aged 30, she had hit a bracket that didn’t gel with the ingenue conception of her. What’s clear is that after 15 years onscreen, Ryder was overdue a break. “The one good thing to come out of everything that happened is that I wasn’t happy where I was,” she told AnOther Magazine back in 2006, the first time she was on our cover. “I wasn’t happy being so famous and being written about all the time. Hollywood people associate movies solely with fame and I didn’t enjoy working in that way any more.”

And so, after a couple of years’ respite in northern California, Ryder set about taking the kind of chewy character parts that originally lured her onto the screen in the first place. She joined up with her longtime friend Keanu Reeves for Richard Linklater’s rotoscoped take on Philip K Dick’s mind-scrambling novel A Scanner Darkly, playing a jittery addict caught in a web of shady government forces. She infused the perfect recipe of pathos and humour into her overdramatic adulterous poet in Rebecca Miller’s The Private Lives of Pippa Lee. And she was electrifying as a washed-up prima ballerina usurped by fresh feet in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan, dark impulses shooting from her mascara-smudged eyes – Ryder kept Bette Davis in All About Eve at the back of her mind for that one. She snipped her eyelashes to play a bruised Yonkers councilwoman in the HBO series Show Me a Hero, after its writer David Simon warned her he didn’t want “Winona eyes” for a character whose gestures of affection constitute a shot of sambuca and a light punch in the arm. Some roles harnessed the connective tissue of Ryder’s own trajectory — the weight of an icon’s fame, the notion of a fall from grace, the nostalgic pangs evoked by a certain era. All confirmed that Ryder is transfixing in a way it’s hard to do the maths on, raising the temperature of a scene with her presence.

That’s something the Duffer Brothers were relying on in 2016, when they made her the North Star of their 80s-set Netflix show Stranger Things. Circling a crew of Indiana kids who battle goo-dripping monsters, Cold War conspiracies and smalltown suburban prejudices, the show’s nostalgic mash-up of Stephen King and Steven Spielberg became phenomenally successful. Ryder felt the echoes of her childhood as keenly as its devoted fans, who revel in the speed-pedalled BMXs, Dungeons & Dragons camaraderie and vintage analogue synth. “I have to tell you, on the first season, one of the hardest reckonings for me was the day the kids held up a record and said, ‘What is this?’ I honestly started welling up with tears. I was like, ‘That’s how we listened to music!’ And there’s nothing like that sound of the needle hitting the vinyl! I’m officially old school because that is still how I listen to music. I miss those tangible things.”

From its debut season, when her character, Joyce Byers, communicates with her abducted son via a flashing knot of Christmas lights, Ryder turned what might have been a neurotic cut-out into a chain-smoking eccentric with a black sense of humour and unguessed-at strengths. The director twins have admitted Joyce wasn’t much more than a devoted mother on the page. But Ryder knows how to spin gold at such moments. “I really fought for her flaws,” she says. “I didn’t want her to be a supermom. I wanted it to reflect the economics of being broke and having to work two jobs and probably having to lean very unhealthily on your older kid.” She says she thought about Mike Nichols’s 1983 drama, Silkwood, based on the life and mysterious death of the nuclear-plant whistleblower Karen Silkwood. “I had a ‘Who Killed Karen Silkwood?’ T-shirt growing up,” she says. “I was so incredibly moved by characters like that, who are just doing the best they can and it’s not enough. Karen is working at this plant, living with her gay best friend, played by Cher, and she’s not doing it for glory or money, she’s trying to do the right thing. I think maybe because Stranger Things was a genre show, I wanted to make Joyce as human as possible. And the only way to really do that is to show we’re contradictory beings.”

When we speak, Ryder is six months into the yearlong production of the fifth and final season – her last foray into the Upside Down. She and her partner of more than 13 years, the designer Scott Mackinlay Hahn, split their time between New York and LA, but Atlanta, where Stranger Things is shot, has increasingly become a third home. “I never thought it was going to be a ten-year thing,” she says. “I mean the kids are in their early twenties now and they were 11 or 12 when it started.” Few actors could better understand the disorientating rollercoaster her young co-stars have ridden in that time. Ryder feels as protective of them as she is onscreen. “With TV you’re in someone’s house as opposed to their movie theatre. They feel like they know you, that you’re theirs,” she says. “I get it, because I love detective shows – DCI Jane Tennison? You get to feel very close to these people. But it’s especially tricky if it’s growing kids. They should be off limits.”

“I always felt lucky that I was considered kind of a weirdo for enough time … I was still around really inappropriate behaviour. But I felt like my identity protected me in a way” – Winona Ryder

Working with children the same age she was during her early years navigating 80s Hollywood has emphasised for her how unregulated it was. “I never had an HR meeting until #MeToo! It’s ultimately very good, but I was in my late forties by then,” she says. “I used to feel very guilty that because of my parents’ choices and keeping me home, I wasn’t out there pounding the pavement. My heart breaks for the kids who weren’t protected. When I was doing Heathers, I stayed with these young actresses in their twenties that my parents knew and trusted, and I would go with them to their auditions for commercials sometimes. I’d be in the waiting room and see through the open door that they were told to take their clothes off – not completely – but really humiliating stuff that was not OK at all. The lines were so blurry. With everything that’s happened in the past six years, it takes remembering something and thinking about it happening to someone of the same age you were, like Jenna [Ortega] or Sadie [Sink], and it’s like, ‘Five-alarm fire, not OK!’ Because everything back then was always, ‘You’re so sensitive, he’s just kidding. Get a sense of humour.’ I always felt lucky that I was considered kind of a weirdo for enough time … I was still around really inappropriate behaviour. But I felt like my identity protected me in a way.”

Ryder recently found her old Filofax from those child-actor days: “Remember when your whole life was your Filofax? I’ve written, ‘If Lost, Will Reward’ and there’s a stamp of the studio and my old phone number. The front page is a Polaroid from the Beetlejuice set – it’s me and Tim at the Day-o dinner scene,” she says. “I had no idea at the time what Beetlejuice was going to be. But I remember when we wrapped feeling really blue and thinking, how am I ever going to top this?” That life-altering shoot, and the widespread adoration for the film that followed, made stepping back into Lydia’s lace-up boots a little daunting. “I had built up a lot of nerves, because this film is very beloved,” she says. In the end, though, it was like time-travelling back to the moment she and Burton recognised each other as kindred outsiders in that Culver City studio in 1987. “Tim was right there by the camera, almost mirroring me, which is how we made it the first time, and how I grew up – there were no monitors or Video Village back then. I knew he would never do anything to compromise his vision. I’d been thinking, OK, Lydia is popping pills, she’s very lost, she’s on autopilot … But then Tim said something very simple. He said, ‘Let’s try one where you’re really sincere.’ And suddenly I remembered that was his direction to me on the first Beetlejuice – that Lydia might look weird but she’s actually really sincere. Every time I’ve worked with Tim, he would say there might be chaos around me, but what I’m playing is something very real. It blew me away how much it brought back those initial feelings.”

If Burton’s ingenious new spectacle reaffirms his status as a true cinematic one-off, the same can be said of his friend and muse, the self-described weird kid who brought her edge to Hollywood. Never the polished career strategist, today Ryder is the guardian angel of an award-winning show, the star of the year’s most anticipated blockbuster and, 36 years after her breakthrough as the peculiar girl who eats Chinese takeout in a mourning veil, still the nonconformist we root for, offscreen and on.

Hair: Jimmy Paul at Susan Price. Make-up: Francelle Daly at 2b Management using LOVE+CRAFT+BEAUTY. Manicure: Megumi Yamamoto at Susan Price using UKA. Set design: Stefan Beckman at Exposure NY. Digital tech: Tadaaki Shibuya. Photographic assistants: Shri Parameshwaran, Nick Krasznai and Tony Jarum. Styling assistant: Precious Greham. Seamstress: Hailey Desjardins. Hair assistant: Tiffany Beach. Make-up assistant: Madrona Redhawk. Set-design assistants: Syvash Jefferson and Zac Pepere. Production: Gracey Connelly. Retouching: Gloss Studio. Special thanks to Smashbox Studios

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 12 September 2024. Pre-order here.

and integrate them seamlessly into the new content without adding new tags. Ensure the new content is fashion-related, written entirely in Japanese, and approximately 1500 words. Conclude with a “結論” section and a well-formatted “よくある質問” section. Avoid including an introduction or a note explaining the process.